Abstract

We present the first numerical simulation of actin-driven propulsion by elastic filaments. Specifically, we use a Brownian dynamics formulation of the dendritic nucleation model of actin-driven propulsion. We show that the model leads to a self-assembled network that exerts forces on a disk and pushes it with an average speed. This simulation approach is the first to observe a speed that varies nonmonotonically with the concentration of branching proteins (Arp2/3), capping protein, and depolymerization rate, in accord with experimental observations. Our results suggest a new interpretation of the origin of motility. When we estimate the speed that this mechanism would produce in a system with realistic rate constants and concentrations as well as fluid flow, we obtain a value that is within an order-of-magnitude of the polymerization speed deduced from experiments.

INTRODUCTION

There is a type of biological motility, used in a form of cell crawling (1) and by intracellular pathogens such as Listeria monocytogenes (2), that is driven not by motor proteins but by biological self-assembly of the protein actin. During this process, ATP hydrolysis and activation of the protein complex Arp2/3 drive actin self-assembly from monomers (G-actin) to branched networks of filaments (F-actin) (3), thus providing the necessary thermodynamic free energy to push a bacterium or a cell forward (4,5). This driven, nonequilibrium self-assembly process is regulated by a cadre of proteins. It is now possible to drive a latex bead through a buffer solution containing only these proteins (6–9). Such beads travel through solution propelled by a dense branched actin network at their rear, demonstrating that nonequilibrium self-assembly of F-actin is sufficient to drive motility.

The standard biochemical model for the regulation of actin-self-assembly-driven motility is the dendritic nucleation model (3,10,11). In this model, actin self-assembles (or polymerizes) into filaments preferentially at one end (the barbed end) and de-polymerizes preferentially at the other end (the pointed end). Proteins such as WASP at the moving surface (the rear end of the Listeria bacterium or moving latex bead, or the leading edge of the membrane of a crawling cell) recruit and activate the Arp2/3 protein complex. The activated Arp2/3 catalyzes the nucleation of new branches from preexisting actin filaments, thus creating new growing barbed ends near the moving surface. To sustain motion, two other essential proteins regulate the turnover of actin monomers: severing protein (ADF), which raises the depolymerization rate by severing filaments in two, and capping protein (Cap), which covers barbed ends and prevents further growth. Thus, filaments just behind the moving surface at the front of the branched network tend to grow due to Arp2/3 and WASP, while filaments at the far end of the branched network tend to depolymerize away, due to ADF and Cap.

A key physical question arises: how does the self-assembly of a branched network generate forces and produce motion? Many models have been developed to show how the polymerization of a single actin filament can produce a force (12–22). Other models show how the dendritic nucleation model creates a branched network morphology (23–28). Relatively few models have considered how polymerization of a branched network might lead to force generation; of these, some treat the network as an elastic continuum (29–31). Only three approaches explicitly incorporate the morphology of the dendritic nucleation model to produce force and motion (28,32,33). In all three of these simulation models, mass is not conserved; monomers spring into existence and become capable of exerting forces only when they join filaments, and vanish when they fall off. As a result, matter is created just behind the moving surface, leading to motility as an artifact.

In this article, we use Brownian dynamics to demonstrate that force and motion can indeed emerge from the growth of a branched network in a physically consistent model. We demonstrate that our model is the first to capture key properties of the dendritic nucleation model by reproducing the characteristic dependence of speed on the concentrations of Arp2/3, capping protein, ADF, and actin (8,34,35). Our simulation suggests a new understanding of the mechanism driving motility: the disk emits activated Arp2/3 complex, which gives rise to a buildup of F-actin just behind the disk. If there is a repulsive interaction between the disk and the actin, the disk will move forward to avoid the actin recruited by Arp2/3. We propose explicit experiments to test this new picture.

METHODS

Here we describe the model, which we solve numerically using Brownian dynamics methods.

Interactions

All actin monomers, whether free or bound in filaments, are modeled as spheres of size σ ≡ 5 nm that repel each other with a soft repulsive potential of

|

(1) |

with K = 100 kBT/σ2. Monomers within filaments interact with each other via a bond potential of

|

(2) |

with K = 100 kBT/σ2 as in Eq. 1. We introduce a bending potential that imparts stiffness to the filament (69):

|

(3) |

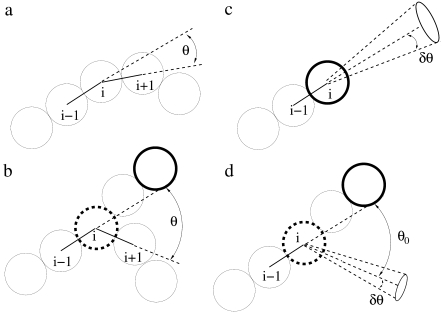

We use KB = 100 kBT in most of our runs, but have also explored the effect of filament stiffness by using KB = 0 kBT and KB = 1000 kBT. In Eq. 3, θ is the angle between the bond connecting monomer i − 1 to monomer i and the bond connecting monomer i to monomer i + 1 along a filament and θ0 = 0° (see Fig. 4 a). Note that i = 1 corresponds to the pointed end. If monomer i is tagged by Arp2/3 complex and is at a y junction (36–38), there is also a bending potential of the same form as Eq. 3, where θ is the angle between the bond connecting monomer i at the junction to monomer i + 1 on the branch, and the bond connecting monomer i − 1 on the parent filament to monomer i at the junction (see Fig. 4 b). In that case, θ0 = 70° (36).

FIGURE 4.

Schematic showing the definition of angles used in the bending potential energy in Eq. 1. (a) For a monomer i along the filament, there is a bending cost associated with changes of the angle θ away from θ0 = 0. (b) If monomer i is tagged by Arp2/3 and is at a y junction, there is also a bending cost associated with changes of the angle θ with respect to θ0 = 70°. (c) A free monomer j (not shown) can be added to monomer i at a growing end if its center is within a range δr of separations Rij such that σ − δr < Rij < σ, and a range δθ of angles θij at ∼θ0 = 0 such that |cos θij − cos θ0| < δθ. (d) A free monomer j (not shown) can be added as the first monomer along a branch if: monomer i has been tagged by Arp2/3 complex; the separation Rij satisfies σ − δr < Rij < σ; and the angle θij satisfies |cos θij − cos θ0| < δθ, where θ0 = 70°.

For the moving surface, we use a flat disk of thickness σ and radius 10σ (39). Monomers are repelled from the disk with a potential similar to Eq. 1. Note that we have not included any attractive interaction between filaments and the disk. As a result, the branched network is not attached to the disk, unlike the experimental system (29,40–43). Model calculations (A. Gopinathan and A. J. Liu, unpublished) suggest that the speed v(Eb) at binding energy Eb is given by v(Eb) = α(Eb)v(Eb = 0), where α(Eb) does not depend on v(Eb = 0). This article focuses on the physical origin of v(Eb = 0). We note that even without including binding, we are able to reproduce nontrivial, qualitative trends observed experimentally. Thus, it appears that binding may not be essential to understanding all aspects of motility. Here, we have also neglected cross-linking of the filaments because it is known that neither cross-linking nor bundling proteins are needed for motility (8).

Branching

In our model, the Arp2/3 complex is treated as a point particle that is generated (activated) at the center of one side of the disk and diffuses away from it. We have also generated Arp2/3 at random points on one side of the disk and found that this makes no difference to the speed. By generating Arp2/3 from one side of the disk but not the other, we break symmetry. As a result, the branched actin network self-assembles on one side of the disk and drives it, on average, in a specific direction (which we define as the +z direction). If Arp2/3 collides with the disk, it is reflected without exerting a force on the disk. If Arp2/3 collides with a monomer in a filament, it sticks to it and activates the monomer for branching. The Arp2/3 remains stuck to the branching monomer until the branch falls off, the branching monomer is depolymerized, or the Arp2/3 spontaneously dissociates. Once it detaches from the monomer, it is regenerated near the disk. This procedure is designed to generate a physically reasonable Arp2/3 distribution near the disk surface (34,45) without imparting forces to it as an artifact. We have confirmed this by running simulations with K+ set to zero so that polymerization cannot occur. In this case, the emission of Arp2/3 from the disk does not lead to any motion of the disk.

Note that we do not restrict branching to the barbed end. Because the number of barbed-end monomers is low compared to the total number of monomers in filaments, side branching (10,36,46) is the dominant branching mechanism in our model.

Equations of motion

All particles in our system (free monomers, monomers in filaments, Arp2/3, and the disk) evolve according to Brownian dynamics (Eq. 4) (47), with corresponding phenomenological friction constants ζ and stochastic random forces F (Eq. 5). Thus, all free monomers, filaments, Arp2/3, and the disk fluctuate in position due to the stochastic random forces acting on them. In addition, they are subjected to forces because of their interactions with each other:

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

The friction constant ζ0 of an actin monomer is taken to be ζ0 = 3πση, where η is the viscosity of the medium. The friction constant of the disk is taken to be ζD = 20ζ0, and that for the Arp2/3 is taken to be ζ0.

We convert our results to real units as follows. The unit of length in our model is the size of the actin monomer, σ = 5 nm. We take the viscosity to be 2.4 cP, as measured experimentally for cell extracts (48). This yields a monomer diffusion coefficient of D ≡ kBT/ζ0 = 36 μm2/s and a characteristic time unit of τ ≡ σ2/(2D) = 0.35 μs.

Boundary conditions

We use periodic boundary conditions. The disk is constrained to move in the z direction only. Most of our results are for a system of size 40σ × 40σ × 80σ. Unless explicitly stated otherwise, we find no discernible differences for system sizes 80σ × 80σ × 80σ and 40σ × 40σ × 160σ under standard conditions (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Values of the parameters used in the simulations compared to those in experiments

| Parameter | In vitro Exp. (ref) | Simulated |

|---|---|---|

|

0.5–15 μm (13) | 0.1 μm |

|

0.1–1 μm (45,68) | 0.1 μm |

| Typical bead diameter | 0.2–2 μm (48) | 0.1 μm |

| Viscosity (η) | 2.4 cP (48) | 2.4 cP |

| D = kBT/3πησ | 36 μm2/s | 36 μm2/s |

| K+ | 11.6 μM−1 s−1 (3)00011.6 μM−1 s−1 (3) | 504 μM−1 s−1 |

| K– | 0.3 s−1 (3) | 28,600 s−1 |

| [G-actin] | 7 μM (8) | 625 μM |

|

270 | 11 |

| Ka | — | ∼K+ |

| Kd | 0.002 s−1 (56) | 28,600 s−1 |

| [Arp2/3] | 0.1 μM (8) | 2.1 μM |

|

N/A | 0.037 |

| KC+ | 8 μM−1 s−1 (46) | — |

| KC– | 0.00042 s−1 (46) | 0 s−1 |

| [Cap] | 0.1 μM (8) | — |

| kC+ = KC+[Cap] | 0.8 s−1 | 14,300 s−1 |

Biochemistry

The next step is to include the self-assembly/biochemistry of the dendritic nucleation model. Our algorithm for actin polymerization is similar to that of Gelbart et al. for nanocolloids (49). We allow polymerization only at the barbed end or at a branching monomer tagged by Arp2/3, and allow depolymerization only at the pointed end.

Polymerization occurs when the center of a diffusing free monomer j is within a distance Rij of the monomer i at the growing end of a filament (see solid rimmed circle in Fig. 4 c), such that

|

(6) |

In addition to satisfying Eq. 6, a free monomer j must also lie within the angular cone

|

(7) |

of monomer i. The angle θ is the angle between the vector from monomer i − 1 preceding monomer i on the filament to monomer i and the vector connecting monomer i to free monomer j (see Fig. 4 c). Here, θ0 = 0°.

Polymerization also occurs when the center of free monomer j is within Rij of monomer i that has been tagged by Arp2/3 as a branching monomer (see dashed rimmed circle in Fig. 4 d). In that case, monomer j must satisfy Eqs. 8 and 9 with θ0 = 70° (see Fig. 4 d).

In all cases, we choose δr and δθ in Eqs. 8 and 9 such that the potential energy change due to polymerization is small relative to the thermal energy kBT. Our choice of parameters (δr = 0.1σ, δθ = 0.02) affects the effective polymerization rate but does not otherwise influence our results. To verify this, we have carried out a systematic calibration of the simulation as a function of polymerization rate (Appendix).

Depolymerization is simulated using a first-order rate constant, K–. During each time step, Δt = 0.001τ, each pointed end is checked for depolymerization as follows: a uniformly distributed random number between [0,1] is chosen and compared to the probability for dissociation during that time step, K–Δt. If the number is smaller than K–Δt, the bond is broken to free the pointed-end monomer. Capping is treated similarly; the probability for a barbed end to become capped during a time step is kC+Δt, where kC+ is the pseudo-first-order rate constants for capping. The probability for a barbed end to become uncapped is KC–Δt, where KC– is the first-order rate for uncapping. Likewise, in each time step, a branch can dissociate from its parent filament with probability KdΔt, where Kd is the debranching rate. Finally, we note that we do not include ADF explicitly, but instead vary the depolymerization rate (50).

SIMULATION MODEL

Relevant timescales within the dendritic nucleation model span six orders of magnitude. The longest timescale is set by kinetic events such as the depolymerization rate (∼1 s) (3), whereas the shortest timescale is determined by diffusion and collision of G-actin monomers (∼1 μs) and the high frequency dynamics of filaments. The wide range of important timescales poses a challenge to computer simulation. Previous approaches avoid this problem by treating free monomers and those in filaments very differently, leading to potential artifacts (51). If one insists on treating free monomers and monomers within filaments consistently, one must use a time step that is small enough to capture their short-timescale dynamics when integrating the equations of motion. On the other hand, to study the steady state, one must be able to reach timescales that are long compared to the slowest reaction rate involved. The compromise that we have chosen is to narrow the range of timescales by increasing the slowest rates, such as the depolymerization rate, by five orders of magnitude and decreasing the filament stiffness (see Table 1). We also use the enhanced depolymerization rate to mimic the action of severing protein (ADF). The details of our model are presented in Methods, above.

To offset some of these changes, we adjust other variables so that the steady-state fluxes are comparable to those observed experimentally. For example, to offset the effect of our artificially high depolymerization rate, we increase the typical concentration of the G-actin monomers such that the ratio of the effective polymerization rate and the depolymerization rate, K+[G-actin]/K–, is close to the typical experimental value.

In testing our model, our aim is not to reproduce numerically accurate results but to capture experimentally observed trends and understand what factors control them. In particular, our goal is to gain insight into the mechanism that leads to motility. We will show that the origin of motility in our system (see Results and Discussion) suggests a possible mechanism for the real system that yields a reasonable speed within a simple order-of-magnitude estimate (see Results and Discussion).

To check that our conclusions do not result from the unphysical parameters we have chosen, we have varied the parameters over a range. For example, most of our runs were carried out for a bending stiffness of KB = 100 kBT (see Eq. 2), corresponding to a persistence length of 0.1 μm. However, we have also shown that when all other parameters are held fixed, we obtain the same speed for KB = 1000 kBT, corresponding to a more realistic persistence length of 1 μm.

We have also checked the dependence of our results on K– and other slow rates by decreasing them and showing that the trends remain the same.

Bulk system

Our simulation model is described in Methods, above. For systems that are spatially isotropic on average, we have shown that the Brownian dynamics results for morphology are in quantitative agreement with a mean-field formulation of the dendritic nucleation model (27). This mean-field formulation was, in turn, shown to be in quantitative agreement with in vitro experiments (36). Thus, our model yields reasonable results for the steady-state bulk system.

Motility

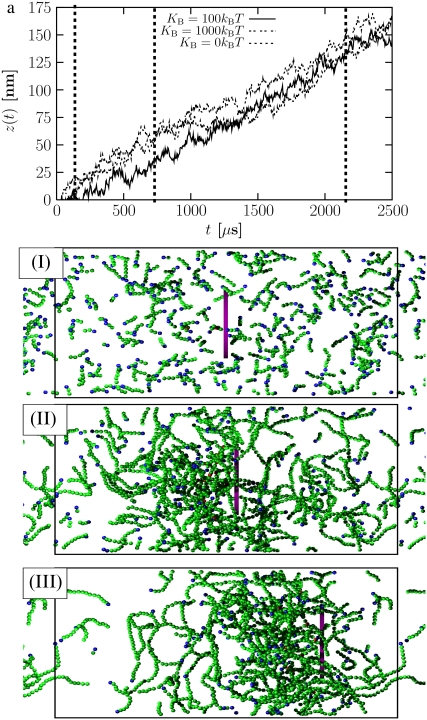

We now break symmetry by introducing a moving surface in the form of a disk, whose back surface (facing the −z direction) emits Arp2/3. This drives self-assembly of a branched network behind the disk, which pushes the disk in the +z direction. We typically begin each run with 5–10% of the actin monomers in dimer form and the rest as free monomers. We begin with some dimers as protofilaments because spontaneous nucleation of filaments, which occurs at a very low rate experimentally (3), is not allowed in our model. We find that the results are not sensitive to the fraction of initial dimers. The dimers and free monomers are initially distributed randomly in the system. Fig. 1 a shows the displacement, z, of the disk as a function of time for a typical simulation run for a filament stiffness Kb = 100 (solid curve). The dashed vertical lines mark the times corresponding to the snapshots (Fig. 1, I–III). In the snapshots, free monomers are not shown. The black box corresponds to the simulation box; we have shown part of the periodic images to the right and left. Snapshot I (in Fig. 1) displays the system at t = 70 μs. At this time, the disk is still very close to its starting position. The dimers have grown into short filaments and are dispersed throughout the box. By t = 700 μms (Fig. 1, snapshot II), a branched F-actin network has formed behind the disk and the disk has moved slightly. By t = 2100 ms (Fig. 1, snapshot III), the disk has moved to the right by nearly one-third of the simulation box.

FIGURE 1.

Disk displacement as function of time for three values of the bending stiffness of filaments, KB = 1000 (dotted), 100 (solid), and 0 (dashed). The vertical dashed lines show the times corresponding to snapshots I–III, namely 70 μs, 700 μs, and 2100 μs, respectively, after the simulation started with monomers and 5% dimers distributed randomly. (Snapshots) Green spheres are monomers in filaments, red spheres are monomers tagged by Arp2/3 for branching, and blue spheres are the pointed ends of filaments. G-actin monomers are not shown. The disk is purple. The black box in each frame marks the boundary of the periodic box.

Fig. 1 a shows that once the disk starts moving, the trajectory is linear. Because there are significant fluctuations in the displacement (9,40), we extract speeds from trajectories that are at least 7000 μs-long (several times longer than that shown in Fig. 1), and average over the final 3500–4200 μs of the trajectory (it takes roughly 1000 μs to reach steady state). The error bars for the speed in all of our figures were obtained from the standard deviation calculated over five separate simulations run under standard conditions (see Table 1).

The typical speed for our simulated systems is 60 μm/s. Our speed is simply determined by the polymerization rate. We use K+ = 504 μM−1 s−1 (see Table 1). To convert this to a net polymerization speed vp, we must multiply by the monomer size, σ = 5 nm, by the free monomer concentration just behind the disk, and a factor that characterizes the structure of the network. A reasonable approximation to this factor is cos (θ), where θ is the angle between the average tangent vector of filaments just behind the disk and the normal to the disk (13). For the conditions corresponding to Fig. 1, [G-actin] ≈ 0.2 mM and cos(θ) = 0.1–0.2. This yields an estimate of the polymerization speed vp ≈ 50–100 μm/s, in good agreement with our result.

The speed found experimentally is significantly slower, with a typical value of a fraction of a micron per minute (7–9). We find that when we decrease the depolymerization rate and G-actin concentration by a factor of 10, leaving the ratio K+[G − actin]/K– fixed, the speed decreases by a factor of ∼10. As Table 1 shows, the value of K+[G − actin]/K– that we use is close to the experimental value, but K– and K+[G-actin] are much higher in our simulation. We would therefore expect our speed to be too high.

It is also possible that part of the difference between our simulated speed and the experimental speed may be due to our neglect of filament binding to the moving surface. Experimentally, it is known that filaments in the branched network bind to the proteins on the disk with active Arp2/3 complex (14,29,40–43). Finite element simulations (A. Gopinathan and A. J. Liu, unpublished) suggest that the inclusion of a binding energy between filaments and the disk slows down the speed significantly and enhances fluctuations around the average speed.

An important and surprising result of our calculation is that the speed is independent of bending stiffness. This is shown in Fig. 1 a, where the speed is the same for systems with bending stiffnesses of KB = 1000 kBT, KB = 100 kBT, and KB = 0 kBT. Note that in the flexible case, we have not shown the initial startup of the disk, which is substantially longer than for stiffer filaments. Our results show that flexible and stiff filament networks exert comparable forces as the filaments polymerize. In all cases, the speed is simply the polymerization speed vp. Thus, the physical origin of motility does not depend sensitively on the bending stiffness of the filaments, as is commonly believed (see Results and Discussion).

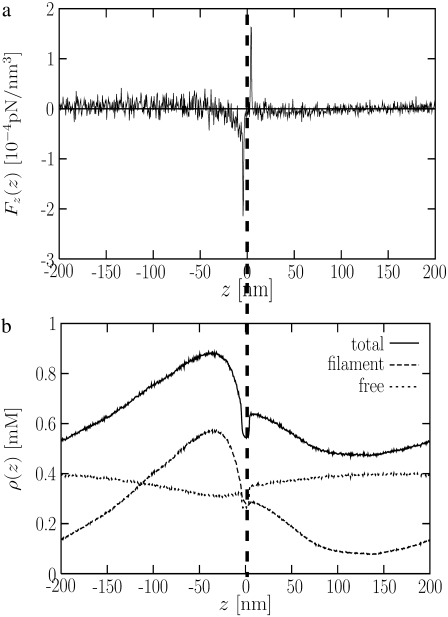

Origin of steady-state force

When the system is in steady state and there is a net force on the disk moving it forward, there must be an equal and opposite net force on the actin. We have calculated the average force density Fz(z) in the z direction at different distances z from the disk (recall that the disk is constrained to move only in the z direction). Fig. 2 shows Fz(z) in the frame of the moving disk, where z = 0 (marked by a vertical dashed line) always marks the position of the disk. Just behind the disk at z < 0, the force on monomers (free or bound in filaments) is large and negative, as expected because the force exerted by these monomers on the disk is positive. Note that this negative force persists out to ∼50 nm behind the disk before it drops nearly to zero. For z > 0, the force near the disk is positive because monomers immediately in front are pushed along by the disk. We have verified that the total average force,  exerted on the actin is equal and opposite to the force on the disk, as it must be. The force on the bead is ∼0.1 pN. Although this force seems small, we note that it is the magnitude of the force required to push a 1-μm bead at the experimentally observed speed, and is also, by construction, the force needed to push the disk at the speed that we observe for the viscosity chosen; we have confirmed that the average force on the disk is related to its average speed by the drag on the disk, ζD, as expected.

exerted on the actin is equal and opposite to the force on the disk, as it must be. The force on the bead is ∼0.1 pN. Although this force seems small, we note that it is the magnitude of the force required to push a 1-μm bead at the experimentally observed speed, and is also, by construction, the force needed to push the disk at the speed that we observe for the viscosity chosen; we have confirmed that the average force on the disk is related to its average speed by the drag on the disk, ζD, as expected.

FIGURE 2.

(a) Average force density on the monomers as a function of position in the frame of the moving disk, which, at z = 0, is denoted by the vertical dashed line. Positive (negative) force implies monomers are being pushed to the right (left). (b) Total local monomer density ρ(z) (solid), local filament monomer density (dashed), and local free monomer density (dotted).

Note that while the negative force extends to 50 nm behind the disk, the total length of the actin comet tail in our simulations is ∼150 nm (Fig. 1, III). Thus, only a relatively small fraction of the network directly behind the disk is subjected to a significant backward force. This result is consistent with the experimental finding that the actin network in the tail is stationary (7,52).

We remark that the force profile shown in Fig. 2 a does not contradict the experimental observation that the shape of the tail can be deformed at distances ≫50 nm from the surface (31), because the moving surface was curved in the experiment and the tail expanded as it moved backward away from the surface, due to entropy or elastic stresses.

The force on the disk can be viewed as the Newton's third-law reaction force to the force in Fig. 2 a on the actin, evaluated at the surface of the disk. Thus, uncovering the origin of the force profile behind the disk should help us to understand motility. The solid curve in Fig. 2 b shows the density profile ρ(z) of actin (note that the free monomer density is nearly constant, with a small dip just behind the disk, so that most of the variation is due to monomers in filament form). In equilibrium, similar density profiles can arise from attraction to the surface. In that case, the chemical potential must be the same everywhere. However, in this steady-state-driven system, the density profile does not arise from attractions—the interaction of actin with the disk is purely repulsive. Instead, the density profile is a nonequilibrium effect, arising from the action of Arp2/3, which is emitted from the disk. (In the real system, Arp2/3 is activated at the surface of the disk, so the disk serves as a source of activated Arp2/3.) The nonequilibrium density profile leads to a pressure gradient, dp/dz = (dp/dρ)(dρ/dz) = −(1/κρ)dρ/dz, where κ is the local compressibility of the branched network. The importance of the compression modulus has been emphasized in previous models (29–31). In our case, the force generated depends not only on κ but on the concentration gradient, dρ/dz. Note that the pressure gradient is equal and opposite to the force per unit volume on the actin, shown in Fig. 2 a. The vanishing of the force near z = −30 nm therefore corresponds to the maximum in the concentration there, where dρ/dz = 0 (Fig. 2 b).

We emphasize that this is not a simple osmotic pressure effect due to free monomers. The density of free monomers (dotted curve in Fig. 2 b) is nearly constant, so that the density gradient arises from F-actin, not G-actin.

The fact that the speed corresponds to the polymerization speed for different filament stiffness suggests that the system adjusts the force exerted on the disk to maintain the speed at the polymerization speed, at least at the small loads studied here. Therefore, it should be possible to understand the underlying mechanism for motility without involving the force. The following interpretation does not invoke forces explicitly, but is equivalent to the above arguments and much simpler. In this picture, Arp2/3 complex recruits F-actin to the vicinity of the disk. The interaction between actin and the disk is repulsive, so the disk moves forward to lower the concentration of actin near the surface. This leads to the steady-state density profile of Fig. 2 b as well as steady-state motion of the disk at the net polymerization speed.

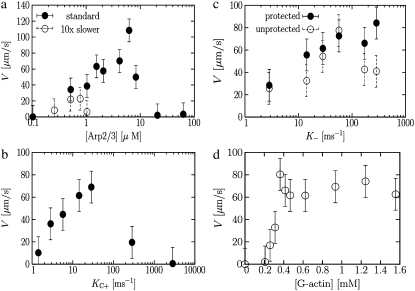

Dependence on protein concentrations

One key observation of experiments is that the speed is a nonmonotonic function of the concentrations of the regulatory proteins involved in the dendritic nucleation model, namely Arp2/3, capping protein, and severing protein. Our simulation model is the first to capture this behavior and to explain the physical origin of the nonmonotonicity.

Fig. 3 a shows that the speed is a nonmonotonic function of Arp2/3 concentration. Similar nonmonotonic behavior has been found experimentally (8). The behavior can be understood as follows. At high Arp2/3 concentrations, most of the excess Arp2/3 is trapped in filaments in the network, forming stubby branches. These short, stubby branches do little to increase the actin concentration behind the disk. However, they do repel actin monomers, lowering the concentration of free monomers at the surface so that fewer of them are available for polymerization. This crowding effect is captured for the first time in our simulation because we treat monomers explicitly. At high Arp2/3 concentration, there appear to be two effects that reduce the speed:

First, the maximum in the density profile in Fig. 2 b broadens as stubby branches proliferate.

Second, the concentration of G-actin at the surface decreases.

With increasing Arp2/3 concentration, the G-actin concentration at the surface drops below its critical value for polymerization and/or the density gradient in F-actin vanishes; at this point, the speed drops to zero.

FIGURE 3.

Concentration dependence of speed. (a) [Arp2/3] dependence. Solid symbols correspond to runs done at the standard rates shown in Table 1. Open symbols correspond to runs done with K–, Kd, and [G-actin] reduced by a factor of 10 and kC+ reduced by 5. In both cases, there is clear nonmonotonic behavior. (b) Capping rate dependence. (c) Depolymerization rate dependence. Symbols correspond to the cases in which Arp2/3 protects (solid) or does not protect (open) the pointed end from depolymerization. (d) [G-actin] dependence.

The open symbols in Fig. 3 a show the speed as a function of [Arp2/3] in the case where the depolymerization rate, debranching rate, and G-actin concentration have all been decreased by a factor of 10 and the capping rate has been decreased by a factor of 5, relative to the values in Table 1. While still high, the difference between the closed and open symbols shows the trend to be expected if we could reduce the parameters to their experimental values. The overall trends are the same in both cases, but the speed is slower, as discussed earlier, and the maximum speed is at lower Arp2/3 concentration, as one might expect. The maximum is much narrower as a function of [Arp2/3], which is more consistent with experimental results (8).

We note that for the typical parameters listed in Table 1 as well as the reduced parameters, the net polymerization rate is comparable to that in the real system. As a result, the filament density in the comet tail is not outrageously high compared to that observed experimentally. We find a filament density of approximately mM in the comet tail for our standard runs, and of ∼0.1 mM for the runs with the reduced reaction rates. This shows that there is some decrease in the amount of F-actin in the comet tail with decreasing depolymerization rate, but the values we find compare reasonably well with previous results of Carlsson (28). One can also estimate the filament density from the Young's modulus, measured to be Y = 103 Pa (29). The Young's modulus for a network of semiflexible polymers with persistence length  and mesh size ξm is (53,54)

and mesh size ξm is (53,54)

|

(8) |

where  in which σ is the filament diameter and c is the monomer concentration. This yields c ≈ 1 mM, as well.

in which σ is the filament diameter and c is the monomer concentration. This yields c ≈ 1 mM, as well.

Since the filament density in our simulation is approximately the same as that in experiments, it is reasonable that the monomer concentration should be reduced near the surface relative to its value in the bulk in the real system. This reduction inevitably leads to a reduction of the polymerization rate with increasing Arp2/3 concentration.

Fig. 3 b shows that the speed is also nonmonotonic with capping protein, in agreement with experiment (8,34). In this case, it is obvious that too much capping will lead to a vanishing speed. If the capping rate is too low, however, the speed also vanishes. This is because capping and branching act synergistically. Capping stops free barbed ends from growing, thus forcing the system to favor branching to generate new growing ends instead of merely lengthening existing filaments (27,34,55). The capping rate at the maximum of the curve in Fig. 3 b is comparable to the debranching rate.

Fig. 3 c shows the dependence of speed on the depolymerization rate. The solid circles correspond to the case in which the Arp2/3 protects the pointed end from depolymerization once it reaches a branch point, and prevents the branch from falling off. There is experimental evidence that Arp2/3 protects the pointed end from depolymerization (10,56). In this case, Fig. 3 c shows that the speed saturates with increasing depolymerization rate. The open circles correspond to the case in which depolymerization proceeds through the branch point, and the branch falls off. This is consistent with experiments showing that when ADF cofilin is present, Arp2/3 no longer protects the pointed end from depolymerization (56). Fig. 3 c shows that in this case, the speed is nonmonotonic and decreases with sufficiently high depolymerization rate. The experiments of Loisel et al. (8) exhibit nonmonotonic dependence, similar to the open circles in Fig. 3 c. This suggests that ADF does indeed prevent Arp2/3 from protecting the pointed end from depolymerization. Note that the two curves are the same at low K–, and begin to deviate from each other near the maximum. This corresponds to where K– is comparable to the debranching rate.

Finally, Fig. 3 d shows the dependence on the overall actin concentration. Again, our results are qualitatively consistent with those of experiment (35). The speed increases with [Actin], because the polymerization rate increases, and saturates at high [Actin] at a maximum polymerization speed, vp. At high [Actin], the concentration of free actin monomers at the surface, needed for polymerization, saturates at roughly 0.1 mM. This saturation apparently occurs because the branched network becomes denser and more difficult for the free monomers to penetrate to reach the disk (24,57,58).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Our simulations show that a physically reasonable formulation of the dendritic nucleation model can lead to motility. We have taken great care to avoid possible artifacts. For example, we treat free monomers at the same level as monomers in filaments so that there is no artificial mass transfer or dynamical discontinuity when monomers join or leave filaments.

We have shown that the speed does not depend on the bending stiffness of the filaments (33,59). This surprising result appears to be consistent with the observation that amoeboid sperm of nematodes (59,60) moves using a structurally different filament composed of major sperm protein (MSP) instead of actin. These MSP filaments assemble into thick bundles (61) which are likely to be much stiffer than actin filaments.

The case we have studied should correspond to the elastic ratchet model without attached filaments (13) because we have not included binding of filaments to the disk. However, our results appear to be at odds with the elastic ratchet model, which should predict a speed that depends on filament stiffness. One possible source of the discrepancy is that the elastic ratchet model assumes that all of the force on the disk is exerted by monomers at the barbed end of filaments. In our simulations, roughly 40% of the force applied to the disk by filaments arises from monomers that are not at the barbed ends for the stiffer filaments we have studied.

Why then is the speed insensitive to the bending stiffness of filaments? Recall that the disk repels actin, so it prefers a low concentration of actin near the surface. It keeps the actin concentration near its surface low by constantly moving forward, away from the buildup of F-actin due to the action of Arp2/3. In this picture, the bending stiffness of filaments is not particularly important to the speed, at least at small loads. However, it is likely that the bending stiffness is important to other attributes of motility, such as the ability to withstand high loads.

This new way of thinking about the origin of motility suggests that other experimental realizations of motility should be possible. Any system that can create a nonequilibrium, steady-state concentration profile should be able to develop a steady-state speed. In a real system, the mechanism is somewhat different because of fluid flow (62). The nonequilibrium chemical potential gradient resulting from the concentration gradient will lead to fluid flow, which will in turn push the disk. It has been understood for some time that a concentration gradient can lead to fluid flow, which will push a suspended particle (62); this effect is known as diffusiophoresis. In the case of actin-polymerization-driven motion of a particle such as a bacterium, bead, or disk, the particle itself gives rise to the nonequilibrium concentration gradient, so the phenomenon is an example of “self-diffusiophoresis” (63). A recent experiment, observing motility of colloids coated on one side with platinum that catalyzes a chemical reaction in solution, is an illustration of a very similar phenomenon (64).

Now that we have identified a potential mechanism, we must ask whether it would be significant in the real system, which we will take to be a micron-sized bead moving in a cell extract. The real system differs from our simulation in two very important ways:

First, the parameter range is very different; the real system has a much lower actin concentration and depolymerization rate constant.

Second, there is fluid flow in the real system but not in our simulation.

To see whether the proposed mechanism is relevant to the real system, we estimate the speed resulting from the mechanism for realistic conditions within a back-of-the-envelope calculation, and compare it to the observed speed. If it is within an order-of-magnitude or so of the experimentally observed speed, our candidate is a reasonable one for the mechanism of motility.

To estimate the speed, we must first estimate the concentration gradient of actin near the surface of the disk. Because there is a short-ranged repulsion between monomers and the disk, the concentration at the disk is approximately zero. The concentration of filaments immediately behind the disk, on the other hand, has been estimated by previous calculations (28,29) to be roughly 1 mM. The scale of the rise is approximately the mesh size of the branched network, roughly 50 nm, so we take the concentration gradient to be ∇c ≈ 1 mM/50 nm.

We must now calculate the resulting pressure gradient. A crude estimate is based on the ideal gas result, where ∇p ≈ kT∇c. In the real system, this pressure gradient will lead to an equal and opposite pressure gradient acting on the fluid, which will lead to fluid flow in the actin comet tail that pushes the disk forward (recall that we assume that the disk prefers to have water near it rather than actin). The magnitude of this flow velocity is related by Darcy's law to the pressure gradient of the actin via the permeability, k,

|

(9) |

where η ≈ 2.4 cP is the viscosity of cell extract (48). The permeability of the actin comet tail can be estimated from calculations for random fiber networks (65) to be k ≈ 10−5 μm2, but this is quite uncertain; it is only clear that it should be quite low. Putting this all together, we obtain a fluid flow speed of v ≈ 1 μm/s. The speed of the bead should be comparable. This speed is within an order-of-magnitude of the observed speed, which is excellent agreement despite the considerable uncertainty in the permeability and pressure estimates. This encouraging result suggests that self-diffusiophoresis is a good candidate for the origin of motility in actin-polymerization-driven systems.

The proposed mechanism of motility is falsifiable. Here, we propose an experiment to test the suggested picture. According to our simulations, the key to motility lies in the concentration gradient of actin near the disk, which decreases as one approaches the disk from behind because the disk repels actin. This depends on the density of actin at the maximum, ρmax, which occurs roughly 30 nm behind the surface in our simulations (see Fig. 2 b), as well as the density at the surface, ρsurf. In the real system, N-WASP or Act-A at the surface not only activates Arp2/3 but also binds F-actin, giving rise to an increase in ρsurf and therefore perhaps decreasing the speed. As the coverage of N-WASP or Act-A increases, both ρmax and ρsurf presumably increase, leaving the difference relatively unaffected. This may be why the speed has been observed to be relatively insensitive to the coverage of Act-A (7) or N-WASP, at least at high coverage (34). To test our proposed mechanism, we therefore propose the following experiment. Suppose one adds another protein to the surface, in addition to N-WASP, that binds F-actin but does not activate Arp2/3. By increasing the coverage of this second protein at fixed coverage of N-WASP, one should be able to increase ρsurf without affecting ρmax. This would decrease the concentration gradient, so we would predict that it would slow down the particle, and possibly even reverse its direction of motion.

The minimal model we have presented here was designed to capture the most important features of the dendritic nucleation model, and we have tested it by reproducing results from experiments on purified proteins. One feature of the experimental system is missing—the binding of filaments to the protein that activates Arp2/3 complex (N-WASp, ActA, etc.). The next step is to incorporate specific binding of filaments to the surface. However, we note that our success in reproducing known nonmonotonic trends with various proteins is encouraging, and suggests that binding may not be essential to understanding all features of actin-based motility.

Once we have incorporated binding, the next step will be to incorporate bundling or cross-linking proteins and to use a curved surface. These extensions will allow us to study situations in which the biology has been perturbed, such as ActA mutants that can hop (66), bundled systems that still move after Arp2/3 has been removed (67), and systems that move faster or slower when cross-linking proteins have been added (31).

In summary, we have conducted the first physically consistent simulations of actin-polymerization-driven motility. These simulations are also the first to include semiflexible filaments and to qualitatively reproduce experimentally measured, nonmonotonic trends with the various proteins involved. Our results suggest a new picture for the mechanism of motility that is experimentally falsifiable.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Haxton, T. C. Lubensky, D. J. Pine, J. M. Schwarz, and D. Vernon for helpful discussions.

The support of the National Science Foundation through grant No. CHE-0613331 and the Penn Materials Research Science and Engineering Center grant No. DMR-0520020 is gratefully acknowledged.

APPENDIX: POLYMERIZATION PARAMETER AND CALIBRATION

It is well known that there is a change of free energy during polymerization; indeed, this is why polymerization occurs in the first place (4). The system gains energy by polymerizing, and gains entropy by depolymerizing. These free energy changes are directly related to the rate constants for polymerization and depolymerization. In the steady-state system with a moving surface, energy is continually added to the system because the system does not obey detailed balance; the system is driven out of equilibrium and the polymerization rate is much higher relative to the depolymerization rate than it would be in equilibrium. In the real system, ATP hydrolysis and Arp2/3 activation provide this additional energy.

In our simulation, we do not explicitly include the free energy changes upon polymerization and depolymerization. Rather, we introduce rate constants that implicitly depend on those free energy changes. In our steady-state system with a moving surface, the ratio of the polymerization rate to depolymerization rate has a constant value that exceeds the equilibrium constant, signifying that the system is out of equilibrium.

In addition to the free energy change upon polymerization, which we take into account using a rate constant, we could also introduce a change in the mechanical energy of a filament upon polymerization. This could be done, for example, by storing energy in distortions of the filament. Any mechanical energy added through polymerization would give rise to forces that could lead to motility. An important question is whether polymerization in itself, with no mechanical energy change in the filaments due to polymerization, can give rise to motility. To address this question, we have designed our simulation model so that minimal mechanical energy is introduced into the filament upon polymerization. In this Appendix, we will show that it is not necessary to introduce a mechanical energy change in the filaments to obtain motility. We note, however, that we cannot rule out the possibility that such a change occurs in the real system.

It has been suggested that ATP hydrolysis may occur during Arp2/3-mediated polymerization at the moving surface (17,18). In absence of direct experimental evidence of such a process, however, we prefer to concentrate on the simplest possible case, where no mechanical energy is added to the system even during Arp2/3-mediated polymerization, to see whether motility and reasonable force generation can still occur.

We cannot completely eliminate any addition of mechanical energy to filaments during the polymerization process. However, we can minimize it as follows. We have chosen the spring constant for monomer-monomer repulsion (Eq. 7) to be the same as the spring constant holding monomers together in filaments (Eq. 8). Thus, when a new bond is formed, the repulsive harmonic interaction is replaced by a full harmonic potential with no energy change at any value of the polymerization parameter δr in Eq. 4. However, it is impossible to avoid a mechanical energy change in the filament due to bending of the filament (Eq. 1, see Fig. 4). The amount of energy change is determined by the parameter δθ in Eq. 5, and is nonzero as long as δθ ≠ 0. We minimize the effect of Eq. 1 by choosing a small value for δθ. To verify that the resulting small change of bending energy does not significantly affect the speed, we also carry out a systematic calibration, as follows.

The range δθ affects not only the change of bending energy stored in the filament due to polymerization, but also the polymerization rate itself. Larger values of δθ lead to larger values of K+. Both the change in mechanical energy and the polymerization rate can, in principle, affect the speed. Here we check whether the dominant contribution to the change in speed with changing δθ arises from the change in K+, and not the change of bending energy. To check this, we first calculate a calibration curve for speed as function of polymerization rate for δθ = 0.02. If changing δθ affects only the polymerization rate, then for different values of δθ, corresponding to different polymerization rates, we should obtain speeds that lie somewhere on the calibration curve.

To calculate the calibration curve, we must first measure the polymerization rate. To do this, we construct a system starting with a fixed small concentration of dimers, free monomers, and no disk. We turn off branching, capping, and depolymerization and measure the rate of depletion of free monomers. The free monomer concentration as function of time is a first-order decay, so we fit it to  where b0 is the initial concentration of free monomers and c0 is the initial concentration of dimers. The fitting parameter K+ is the polymerization rate. The value of K+ for our standard setup is listed in Table 1.

where b0 is the initial concentration of free monomers and c0 is the initial concentration of dimers. The fitting parameter K+ is the polymerization rate. The value of K+ for our standard setup is listed in Table 1.

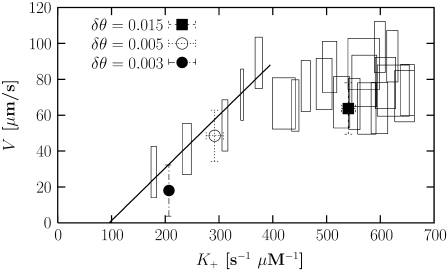

The next step in calculating the calibration curve is to vary the polymerization rate without changing the value of δθ. This can be done without changing the energy of the system by introducing a probability Pb ≤ 1 for capture of a monomer by the barbed end, given that the free monomer satisfies the conditions of Eqs. 6 and 7. In our standard runs, we use Pb = 1, so we can only decrease the polymerization rate by using Pb < 1. The resulting curve for speed versus polymerization rate is shown in Fig. 5 (rectangular points).

FIGURE 5.

Velocity as function of polymerization rate calibration. The data for the calibration points (open rectangles) are obtained with δθ = 0.02. The size of each rectangle corresponds to the error associated with it.

With the calibration curve now in hand, we compute the polymerization rate and velocity for three different values of δθ. As shown in Fig. 5, the speeds observed for δθ = 0.003, 0.005, and 0.015 fall on the calibration curve, as expected. This result demonstrates that δθ affects only the polymerization rate, and that the motility is not caused by sudden changes in the bending energy of filaments undergoing polymerization. In other words, changing δθ only affects the speed through K+ at small δθ; there is no significant contribution from the change of bending energy stored in the filament. Thus, we conclude that it is not necessary to include an explicit mechanical energy change upon polymerization to obtain motility.

Fig. 5 shows that the speed of the disk increases linearly at low polymerization rate and saturates at high polymerization rate. The saturation value of K+ is related to [Arp2/3]; at low K+, the velocity is limited by the rate of creation of new growing ends. A straight line fit to the low-polymerization-rate portion of the curve shows that a threshold polymerization rate is needed to obtain a nonzero speed. This threshold rate yields an estimate of the critical actin concentration required for motility, given K– from Table 1. We find that the critical actin concentration is K–/K+ ∼ 0.2 mM, consistent with what we found before in Fig. 3 d.

Editor: Alexander Mogilner.

References

- 1.Tilney, L. G., and D. A. Portnoy. 1989. Actin filaments and the growth, movement, and spread of the intracellular bacterial parasite. J. Cell Biol. 109:1597–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Condeelis, J. 1993. Life at the leading edge: the formation of cell protrusions. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 9:411–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pollard, T. D., L. Blanchoin, and R. D. Mullins. 2000. Molecular mechanisms controlling actin filament dynamics in nonmuscle cell. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 29:545–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill, T. L., and M. W. Kirschner. 1982. Bioenergetics and kinetics of microtubule and actin filament assembly-disassembly. Int. Rev. Cytol. 78:1–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oosawa, F., and S. Asakura. 1975. Thermodynamics of the Polymerization of Protein. Academic Press, New York.

- 6.Borisy, G. G., and T. M. Svitkina. 2000. Actin machinery: pushing the envelope. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 12:104–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cameron, L. A., M. J. Footer, A. van Oudenaarden, and J. A. Theriot. 1999. Motility of ActA protein-coated microspheres driven by actin polymerization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:4908–4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loisel, T. P., R. Boujemaa, D. Pantaloni, and M.-F. Carlier. 1999. Reconstitution of actin-based motility of Listeria and Shigella using pure proteins. Nature. 401:613–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernheim-Groswasser, A., S. Wiesner, R. M. Golsteyn, M.-F. Carlier, and C. Sykes. 2002. The dynamics of actin-based motility depend on surface parameters. Nature. 417:308–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mullins, R. D., J. A. Heuser, and T. D. Pollard. 1998. The interaction of Arp2/3 complex with actin: nucleation, high affinity pointed end capping, and formation of branching networks of filaments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:6181–6186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cameron, L. A., P. A. Giardini, F. S. Soo, and J. A. Theriot. 2000. Secrets of actin-based motility revealed by a bacterial pathogen. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1:110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peskin, C. S., G. M. Odell, and G. F. Oster. 1993. Cellular motions and thermal fluctuations: the Brownian ratchet. Biophys. J. 65:316–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mogilner, A., and G. F. Oster. 1996. Cell motility driven by actin polymerization. Biophys. J. 71:3030–3045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mogilner, A., and G. F. Oster. 2003. Force generation by actin polymerization. II. The elastic ratchet and tethered filaments. Biophys. J. 84:1591–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burroughs, N. J., and D. Marenduzzo. 2005. Three-dimensional dynamic Monte Carlo simulations of elastic actin-like ratchets. J. Chem. Phys. 123:174908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burroughs, N. J., and D. Marenduzzo. 2006. Growth of a semi-flexible polymer close to a fluctuating obstacle: application to cytoskeletal actin fibers and testing of ratchet models. J. Phys. Condens. Matt. 18:S357–S374. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dickinson, R. B., and D. L. Purich. 2002. Clamped-filament elongation model for actin-based motors. Biophys. J. 82:605–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dickinson, R. B., L. Caro, and D. L. Purich. 2004. Force generation by cytoskeletal filament end-tracking proteins. Biophys. J. 87:2838–2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickinson, R. B., and D. L. Purich. 2006. Diffusion rate limitations in actin-based propulsion of hard and deformable particles. Biophys. J. 91:1548–1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carlsson, A. E. 2000. Force-velocity relation for growing biopolymers. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Phys. Plasmas Fluids Relat. Interdiscip. Topics. 62:7082–7091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlsson, J. Z. A. E. 2006. Growth of attached actin filaments. Eur. Phys. J. E. 21:209–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gholami, A., J. Wilhelm, and E. Frey. 2006. Entropic forces generated by grafted semiflexible polymers. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 74:041803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maly, I. V., and G. G. Borisy. 2001. Self-organization of a propulsive actin network as an evolutionary process. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:11324–11329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mogilner, A., and L. Edelstein-Keshet. 2002. Regulation of actin dynamics in rapidly moving cells: a quantitative analysis. Biophys. J. 83:1237–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaus, T. E., E. W. Taylor, and G. G. Borisy. 2007. Self-organization of actin filament orientation in the dendritic-nucleation/array-treadmilling model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:7086–7091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carlsson, A. E. 2003. Growth velocities of branched actin networks. Biophys. J. 84:2907–2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gopinathan, A., K.-C. Lee, J. M. Schwarz, and A. J. Liu. 2007. Branching, capping, and severing in dynamic actin structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99:058103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carlsson, A. E. 2001. Growth of branched actin networks against obstacles. Biophys. J. 81:1907–1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerbal, F., V. Laurent, A. Ott, M.-F. Carlier, P. Chaikin, and J. Prost. 2000. Measurement of the elasticity of the actin tail of Listeria monocytogenes. Eur. Biophys. J. 29:134–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerbal, F., P. Chaikin, Y. Rabin, and J. Prost. 2000. An elastic analysis of Listeria monocytogenes propulsion. Biophys. J. 79:2259–2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paluch, E., J. van der Gucht, J.-F. Joanny, and C. Sykes. 2006. Deformations in actin comets from rocketing beads. Biophys. J. 91:3113–3122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alberts, J. B., and G. M. Odell. 2004. In silico reconstitution of Listeria propulsion exhibits nano-saltation. PLoS Biol. 2:2054–2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burroughs, N. J., and D. Marenduzzo. 2007. Nonequilibrium-driven motion in actin networks: comet tails and moving beads. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98:238302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wiesner, S., E. Helfer, D. Didry, G. Ducouret, F. Lafuma, M.-F. Carlier, and D. Pantaloni. 2003. A biomimetic motility assay provides insight into the mechanism of actin-based motility. J. Cell Biol. 160:387–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marchand, J.-B., P. Moreau, A. Paoletti, P. Cossart, M.-F. Carlier, and D. Pantaloni. 1995. Actin-based movement of Listeria monocytogenes: actin assembly results from the local maintenance of uncapped filament barbed ends at the bacterium surface. J. Cell Biol. 130:331–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blanchoin, L., K. J. Amann, H. N. Higgs, J.-B. Marchand, D. A. Kaiser, and T. D. Pollard. 2000. Direct observation of dendritic actin filament networks nucleated by Arp2/3 complex and WASP/SCAR proteins. Nature. 404:1007–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Svitkina, T. M., and G. G. Borisy. 1999. Arp2/3 complex and actin depolymerizing factor/cofilin in dendritic organization and treadmilling of actin filament array in lamellipodia. J. Cell Biol. 145:1009–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cameron, L. A., T. M. Svitkina, D. Vignjevic, J. A. Theriot, and G. G. Borisy. 2001. Dendritic organization of actin comet tails. Curr. Biol. 11:130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwartz, I. M., M. Ehrenberg, M. Bindschadler, and J. M. McGrath. 2004. The role of substrate curvature in actin-based pushing forces. Curr. Biol. 14:1094–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuo, S. C., and J. L. McGrath. 2000. Steps and fluctuations of Listeria monocytogenes during actin-based motility. Nature. 407:1026–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Upadhyaya, A., J. R. Chabot, A. Andreeva, A. Samadani, and A. van Oudenaarden. 2003. Probing polymerization forces by using actin-propelled lipid vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:4521–4526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Giardini, P. A., D. A. Fletcher, and J. A. Theriot. 2003. Compression forces generated by actin comet tails on lipid vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:6493–6498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marcy, Y., J. Prost, M.-F. Carlier, and C. Sykes. 2004. Forces generated during actin-based propulsion: a direct measurement by micromanipulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:5992–5997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reference deleted in proof.

- 45.Bailly, M., F. Macaluso, M. Cammer, A. Chan, J. E. Segall, and J. S. Condeelis. 1999. Relationship between Arp2/3 complex and the barbed ends of actin filaments at the leading edge of carcinoma cells after epidermal growth factor stimulation. J. Cell Biol. 145:331–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carlsson, A. E., M. A. Wear, and J. A. Cooper. 2004. End versus side branching by Arp2/3 complex. Biophys. J. 86:1074–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Allen, M. P., and D. J. Tildesley. 1987. Computer Simulation of Liquids. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

- 48.Cameron, L. A., J. R. Robbins, M. J. Footer, and J. A. Theriot. 2004. Biophysical parameters influence actin-based movement, trajectory, and initiation in a cell-free system. Mol. Biol. Cell. 15:2312–2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gelbart, W. M., R. P. Sear, J. R. Heath, and S. Caney. 1999. Array formation in nano-colloids: theory and experiment in 2D. Faraday Discuss. 112:299–307. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carlier, M.-F., V. Laurent, J. Santolini, R. Melki, D. Didry, G.-X. Xia, Y. Hong, N.-H. Chua, and D. Pantaloni. 1997. Actin depolymerizing factor (ADF/cofilin) enhances the rate of filament turnover: implication in actin-based motility. J. Cell Biol. 136:1307–1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee, K.-C., and A. J. Liu. 2008. Numerical simulations of actin-polymerization-driven motility. ACS Symposium. To be published.

- 52.Theriot, J. A., T. J. Mitchison, L. G. Tilney, and D. A. Portnoy. 1992. The rate of actin-based motility of intracellular Listeria monocytogenes equals the rate of actin polymerization. Nature. 357:257–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frey, E., K. Kroy, and J. Wilhelm. 1998. Physics of solutions and networks of semiflexible macromolecules and the control of cell function. ArXiv:cond-mat/9808022.

- 54.Gardel, M. L., J. H. Shin, F. C. MacKintosh, L. Mahadevan, P. Matsudaira, and D. A. Weitz. 2004. Elastic behavior of cross-linked and bundled actin networks. Science. 304:1301–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carlsson, A. E. 2004. Structure of autocatalytically branched actin solutions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92:238102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blanchoin, L., T. D. Pollard, and R. D. Mullins. 2000. Interactions of ADF/cofilin, Arp2/3 complex, capping protein and profilin in modeling of branched actin filament networks. Curr. Biol. 10:1273–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Noireaux, V., M. Golsteyn, E. Friederich, J. Prost, C. Antony, D. Louvard, and C. Sykes. 2000. Growing an actin gel on spherical surfaces. Biophys. J. 78:1643–1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Plastino, J., I. Lelidis, J. Prost, and C. Sykes. 2004. The effect of diffusion, depolymerization and nucleation promoting factors on actin gel growth. Eur. Biophys. J. 33:310–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roberts, T. M., and M. Stewart. 2000. Acting like actin: the dynamics of the nematode major sperm protein (MSP) cytoskeleton indicate a push-pull mechanism for amoeboid cell motility. J. Cell Biol. 149:7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bottino, D., A. Mogilner, T. Roberts, M. Stewart, and G. Oster. 2002. How nematode sperm crawl. J. Cell Biol. 115:367–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.King, K. L., M. Stewart, and T. M. Roberts. 1994. Supramolecular assemblies of the Ascaris suum major sperm protein (MSP) associated with amoeboid cell motility. J. Cell Sci. 107:2941–2949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Anderson, J. L. 1989. Colloid transport by interfacial forces. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 21:61–99. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Golestanian, R., T. B. Liverpool, and A. Ajdari. 2005. Propulsion of a molecular machine by asymmetric distribution of reaction products. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94:220801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Howse, J. R., R. A. L. Jones, A. J. Ryan, T. Gough, R. Vafabakhsh, and R. Golestanian. 2007. Self-motile colloidal particles: from directed propulsion to random walk. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99:048102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Koponen, A., D. Kandhai, E. Hellen, M. Alava, A. Hoekstra, M. Kataja, K. Niskanen, P. Sloot, and J. Timonen. 1998. Permeability of three-dimensional random fiber webs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80:716–719. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lasa, I., E. Gouin, M. Goethals, K. Vancompernolle, V. David, J. Vandekerchhove, and P. Cossart. 1997. Identification of two regions in the N-terminal domain of ActA involved in the actin comet tail formation by Listeria monocytogenes. EMBO J. 16:1531–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brieher, W. M., M. Coughlin, and T. J. Mitchison. 2004. Fascin-mediated propulsion of Listeria monocytogenes independent of frequent nucleation by the Arp2/3 complex. J. Cell Biol. 165:233–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Podolski, J. L., and T. L. Steck. 1990. Length distribution of F-actin in Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Biol. Chem. 265:1312–1318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rapaport, D. C. 1995. The Art of Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.