Abstract

Calmodulin (CaM) mediates Ca-dependent regulation of numerous pathways in the heart, including CaM-dependent kinase (CaMKII) and calcineurin (CaN), yet the local Ca2+ signals responsible for their selective activation are unclear. To assess when and where CaM, CaMKII, and CaN may be activated in the cardiac myocyte, we integrated new mechanistic computational models of CaM, CaMKII, and CaN with the Shannon-Bers model of excitation-contraction coupling in the rabbit ventricular myocyte. These models are validated with independent in vitro data. In the intact myocyte, model simulations predict that CaM is highly activated in the dyadic cleft during each beat, but not appreciably in the cytosol. CaMKII-δC was almost insensitive to cytosolic Ca due to relatively low CaM affinity. Dyadic cleft CaMKII exhibits dynamic frequency-dependent responses to Ca, yet autophosphorylates only when local phosphatases are suppressed. In contrast, dyadic cleft CaN in beating myocytes is predicted to be constitutively active, whereas the extremely high affinity of CaN for CaM allows gradual integration of small cytosolic CaM signals. Reversing CaM affinities for CaMKII and CaN also reverses their characteristic local responses. Deactivation of both CaMKII and CaN seems dominated by Ca dissociation from the complex (versus Ca-CaM dissociation from the target). In summary, the different affinities of CaM for CaMKII and CaN determine their sensitivity to local Ca signals in cardiac myocytes.

INTRODUCTION

Calcium is a highly versatile second messenger in the heart, playing a central role in the regulation of both excitation-contraction (EC) coupling and excitation-transcription coupling. However, how these short- and long-term Ca-dependent functions are selectively regulated is an important and unanswered question in cardiac biology (1,2). Many of the Ca-dependent pathways are channeled through the same Ca sensor, calmodulin (CaM) (3), so it is unclear how these pathways can selectively respond to external stimuli in a context-dependent manner.

Ca signaling is increasingly recognized to be compartmented (4), and local control of Ca signaling pathways could provide a mechanism for context-dependent signaling. Furthermore, Ca-CaM-dependent signaling proteins exhibit a large range of affinities that may affect how they respond to local Ca signals. Calcineurin (CaN), a protein phosphatase thought to play a major role in cardiac hypertrophy, binds Ca4CaM at a “high” affinity: Kd ∼ 28 pM (5). In contrast, CaM-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), which regulates apoptosis, transcription, and excitation-contraction coupling, binds Ca4CaM at a lower affinity: Kd ∼ 33.5 nM for the cardiac (δ) isoform (6). Here, we integrate an experimentally validated computational model of cardiac myocyte excitation-contraction coupling (7,8) with new reaction models derived from the biochemical literature to determine when and where CaM, CaN, and CaMKII are activated by local Ca signals (see Fig. 1 A). This mechanistic model predicts that CaMKII is responsive only when targeted to Ca release sites such as the dyadic cleft, CaN is only responsive to gradual changes in the lower-amplitude cytosolic Ca signals, and these diverging responses can be quantitatively explained by their different affinities for CaM. These results support the idea that diverse CaM binding affinities may facilitate selective regulation of Ca-dependent pathways by fine-tuning sensitivity to particular local Ca signals.

FIGURE 1.

Model of calmodulin (CaM)-dependent signaling in cardiac myocytes. (A) Compartmental model schematic of cardiac myocyte EC coupling (7) incorporating CaM, CaMKII, and CaN signaling in thedyadic cleft and cytosol, as described in Methods. (B) Reaction map for cooperative Ca binding of 2 Ca to CaM sequentially to the C-terminal and then N-terminal EF hands, along with binding of CaM “buffers”. (C) Probabilistic model of CaMKIIδ subunit switching between inactive (Pi), inactive Ca2CaM-bound (Pb2), active Ca4CaM-bound (Pb), Thr287-autophosphorylated with Ca4CaM trapped (Pt), and Thr287-autophosphorylated but CaM-autonomous (Pa) or Ca2CaM-bound (Pt2) states. (D) Reaction map for reversible binding of CaM, Ca2CaM, and Ca4CaM to CaN.

METHODS

Equations and parameters, with references for all new model components, are detailed in the Appendix, but their motivation is provided here. An overall model schematic is shown in Fig. 1 A, with detailed diagrams of the reactions for individual modules in Fig. 1, B–D. Model parameters were obtained from the biochemistry literature (see Tables 1–3) and predictions were validated with experimental data from the literature, as shown in Figs. 2 and 3. Several parameters were derived from the principle of detailed balance. Detailed balance (microscopic reversibility) requires that at chemical equilibrium, the chemical-potential difference of all reactions is zero, which constrains the product of equilibrium constants in a reaction loop to equal 1 (9). All simulations were performed in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) using the stiff ode15s solver, and code is freely available on request.

TABLE 1.

Ca/CaM binding and CaM buffering parameters

| Parameter | Value | Units | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| k20 | 10 | s−1 | 2 Ca dissociation from CaM | (13)* |

| k02 | k20/Kd02 | μM−2 s−1 | 2 Ca association with CaM | (10,11)† |

| k42 | 500 | s−1 | 2 Ca dissocation from CaM | (13)* |

| k24 | k42/Kd24 | μM−2 s−1 | 2 Ca association with CaM | (10,11)† |

| k0Boff | 0.0014 | s−1 | CaM dissociation from Buffer | (23)* |

| k0Bon | k0Boff/0.2 | μM−1 s−1 | CaM association with Buffer | (23)* |

| k2Boff | k0Boff/100 | s−1 | Ca2CaM dissocation from Buffer | (23)‡ |

| k2Bon | k0Bon | μM−1 s−1 | Ca2CaM association with Buffer | — |

| k4Boff | k0Boff/100 | s−1 | Ca4CaM dissocation from Buffer | (23)‡ |

| k4Bon | k0Bon | μM−1 s−1 | Ca4CaM association with Buffer | — |

| k42B | k42 | s−1 | 2 Ca dissocation from CaMBuffer | Detailed balance† |

| k24B | k24 | μM−2 s−1 | 2 Ca association with CaMBuffer | — |

| k20B | k20/100 | s−1 | 2 Ca dissocation from CaMBuffer | Detailed balance† |

| k02B | k02 | μM−2 s−1 | 2 Ca association with CaMBuffer | — |

Parameters are direct (*), derived (†), or estimated (‡) from cited sources.

TABLE 2.

CaMKII reaction parameters

| Parameter | Value | Units | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kbi | 2.2 | s−1 | Ca4CaM dissociation from Pb | (6,16)* |

| kib | kbi/33.5e-3 | μM−1 s−1 | Ca4CaM association with Pi | (6)* |

| kb2i | 5kib2 | s−1 | Ca2CaM dissociation from Pb2 | (18)* |

| kib2 | kib | μM−1 s−1 | Ca2CaM association with Pi | — |

| kb42 | k42*33.5e-3/5 | s−1 | 2 Ca dissociation from Pb | Detailed balance† |

| kb24 | k24 | μM−2 s−1 | 2 Ca association with Pb2 | — |

| kta | kbi/1000 | s−1 | Ca4CaM dissociation from Pt | (16,17)* |

| kat | kib | μM−1 s−1 | Ca4CaM association with Pa | (17)* |

| kt2a | 5kib | s−1 | Ca2CaM dissociation from Pt2 | (18)* |

| kat2 | kib | μM−1 s−1 | Ca2CaM association with Pa | — |

| kt42 | k42*33.5e-6/5 | s−1 | 2 Ca dissociation from Pt | Detailed balance† |

| kt24 | k24 | μM−2 s−1 | 2 Ca association with Pt2 | — |

| kPP1 | 1.72 | s−1 | Thr287 dephosphorylated | (20)* |

| KmPP1 | 11.5 | μM | Thr287 dephosphorylated | (20)* |

Parameters are direct (*) or derived (†) from cited sources.

TABLE 3.

CaN reaction parameters

| Parameter | Value | Units | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kCaNCaoff | 1 | s−1 | 2 Ca dissociation from Ca4CaN | (70)* |

| kCaNCaon | kCaNCaoff/0.5 | μM−2 s−1 | 2 Ca association with Ca2CaN | (11)* |

| kCaN4off | 1.3e-3 | s−1 | Ca4CaM dissociation from CaN | (5)* |

| kCaN4on | 46 | μM−1 s−1 | Ca4CaM association with CaN | (5)* |

| kCaN2off | 2508 kCaN4off | s−1 | Ca2CaM dissociation from CaN | (11)† |

| kCaN2on | kCaN4on | μM−1 s−1 | Ca2CaM association with CaN | — |

| kCaN0off | 165 kCaN2off | s−1 | CaM dissociation from CaN | (11)† |

| kCaN0on | kCaN2on | μM−1 s−1 | CaM association with CaN | — |

| k20CaN | k20/165 | s−1 | 2 Ca dissociation from CaN | Detailed balance† |

| k02CaN | k02 | μM−2 s−1 | 2 Ca association with CaN | — |

| k42CaN | k42/2508 | s−1 | 2 Ca dissociation from CaN | Detailed balance† |

| k24CaN | k24 | μM−2 s−1 | 2 Ca association with CaN | — |

Parameters are direct (*) or derived (†) from cited sources.

FIGURE 2.

In vitro validation of model components. (A) Model-predicted Ca binding to CaM at 1 mM or 6 mM [Mg2+] and 100 mM [K+] (experimental data from Stemmer and Klee (11)). (B) Predicted [Ca] versus CaN activity for 0.03 and 0.3 μM [CaM, (experimental data from Stemmer and Klee (11)). (C and D) Predicted [CaM] versus CaM-dependent CaMKIIδ activity (C) and CaMKIIδ-Thr287 activity (D) (independent experimental data from Gaertner et al. (6)). (E) Predicted [Ca] versus CaM-dependent CaMKIIδ activity, compared with independent CaMKIIα data from Bradshaw et al. (20). (F) Predicted Thr287P-dependent CaMKIIδ activity for 0 or 2.5 μM [PP1] (independent CaMKIIα data from Bradshaw et al. (20)).

FIGURE 3.

Model of CaM buffering. (A) Predicted kinetics of CaM/buffer interaction in permeabilized cardiac myocytes, with slower dissociation at high [Ca] (experimental data from Wu and Bers (23)). (B) As [Ca] increases, buffered CaM is predicted to switch from CaMB (solid line) to Ca2CaMB (dashed line) to Ca4CaMB (dotted line).

Calmodulin (CaM) module

Calmodulin binds four Ca ions: two to the carboxyl or C-terminal EF hand (forming Ca2CaM) and then two to the amino or N-terminal EF hand (forming Ca4CaM). We adapt a previous equilibrium model of Ca binding that includes [K] dependence (10), to which we added a biphasic dependence on [Mg] (11) by estimating intrinsic binding constants, as described previously (12). As Ca binding is cooperative within each EF hand (10), we simplified Ca binding to a sequential two-step process (see Fig. 1 B), where at physiologic [K] and [Mg], C-terminal and N-terminal EF hands have apparent Kds of 3.1 and 24 μM, respectively. We have added kinetics by incorporating consensus fast N-terminal (500 s−1) and slow C-terminal (10 s−1) off rates as measured by stopped-flow experiments and NMR (13). The resulting model fairly accurately predicts overall Ca binding (Fig. 2 A) and kinetics for a wide range of [Ca], [K], and [Mg] in a manner consistent with many prior studies (11–13).

Under transient conditions, the low-affinity N-terminal lobe of CaM may potentially bind Ca before the C-terminal lobe does, as N-terminal kinetics are much faster (14). To examine whether N-terminal Ca2CaM is prominent in the context of our cardiac myocyte model, we added this state and compared the predictions of four-state versus three-state CaM models for dyadic and cytosolic Ca transients. We found that under the conditions examined here, N-terminal Ca2CaM was insignificant and the two models gave equivalent predictions (see the Supplementary Material, Fig. S1, Data S1). Therefore, the three-state CaM model was retained in our studies, as it considerably reduces the number of uncertain parameters and states required to model interactions between CaM and CaM targets.

CaMKIIδ activation module

CaMKII is a multimeric enzyme composed of 10–12 similar subunits, each of which can bind Ca4CaM for activation and, once activated, can autophosphorylate neighboring subunits at Thr287 to sustain activation (15). Thr287-phosphorylated subunits bind Ca4CaM very tightly (16), yet retain activity even when CaM dissociates. Here, we adapted a previous CaMKII autophosphorylation model (6,17), where the autophosphorylation rate constant is an increasing cubic function of the average number of active subunits in the CaMKII holoenzyme. This captures the qualitative cooperative features of CaMKII intraholoenzyme autophosphorylation (e.g., multiple subunits) while retaining characteristics of a simple model that has been shown to be consistent with steady-state and kinetic experimental data (6,17). To reflect differences for the cardiac CaMKIIδ isoform, we incorporated recent data for Ca4CaM/CaMKIIδ affinity and rate of CaMKIIδ autophosphorylation (6). In nonsaturating Ca/CaM conditions (like in vivo), Ca2CaM may bind CaMKII and then recruit additional Ca to form active Ca4CaM/CaMKII, even though Ca2CaM/CaMKII itself exhibits <7% activity (18). Likewise, Ca dissociation from Ca4CaM/CaMKII may be an important inactivation pathway (16,19). Therefore, we included Ca/Ca2CaM/CaMKII reactions (assuming no Ca2CaM/CaMKII activity), as well as CaMKII dephosphorylation by protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) (20) in our model. The six modeled CaMKII states (see Fig. 1 C) are inactive (Pi); Ca2CaM-bound (Pb2); Ca4CaM-bound (Pb); Thr287P and Ca4CaM-bound (Pt); Thr287P and Ca2CaM-bound (Pt2); and Thr287P but CaM-autonomous (Pa). All active CaMKII states (Pb, Pt, Pt2, Pa) were assumed to have 100% activity, although the model was insensitive to this assumption because Pt2 and Pa were less occupied in these studies. As shown in Fig. 2, C–E, and described in the Results section, this model accurately predicts the multiple relationships between [Ca], [CaM], [PP1], and CaMKII activity seen experimentally.

CaN activation module

Calcineurin binds Ca-saturated CaM (Ca4CaM) with very high affinity (21). Recent kinetic experiments have directly measured kinetic rates of CaM/CaN interaction, finding a Kd of 28 pM (5). Stemmer and Klee measured Ca affinities of CaM in the presence and absence of CaN's CaM binding domain (11), which we use together with detailed balance to derive relative affinities of CaN for Ca2CaM and CaM. The use of relative affinities accounts for the higher affinity of CaM for intact CaN than for CaN's CaM binding domain alone (11). Although the number of Ca ions needed to support CaN activity has not been measured directly, we assume that Ca4CaM is required for activity based on the high Hill coefficient (n = 3) for CaN activity (11).

CaN's constitutively bound subunit, calcineurin B, binds four Ca ions, which stimulates 10% CaN activity but is also a prerequisite for CaM binding (11,22). We model only binding of the second pair of Ca ions to calcineurin B (Kd = 0.5 μM), because the first two Ca sites are saturated even in the presence of strong Ca chelators (Kd = 0.01 μM) (11). We incorporated the above reaction mechanisms into a multistep binding model, where Ca4CaMCaN exhibits 100% activity, whereas Ca4CaN, CaMCaN, and Ca2CaMCaN exhibit 10% activity (see Fig. 1 D). The predicted relationships between [Ca], [CaM], and CaN activity were validated against experimental data from Fig. 1 of Stemmer and Klee (11) that were not used to parameterize the model (Fig. 2 B).

CaM buffering

It was found in a recent study that measured CaM buffering in resting cardiac myocytes that only ∼60 nM of the total 6 μM CaM is free in the cytosol (23). Furthermore, CaM dissociates from these intracellular targets ∼100 times more slowly at 500 nM [Ca] than at 100 nM (23). To reflect this understanding in our model, we lumped all CaM targets not explicitly included in our model into a single CaM buffer with 100-fold slower dissociation of CaM when in Ca-bound states than when Ca free (see Fig. 1 B). Estimating free CaM buffers to be ∼20 μM (3) and free CaM at rest to be 60 nM (23), the “Ca free” dissociation constant between CaM and CaM buffer “B” was calculated to be 0.2 μM. The principle of detailed balance was used to determine consistent affinities of Ca for CaM/B complexes. This model, summarized in Fig. 1 B, was sufficient to capture the known characteristics of CaM buffering, such as limited free CaM at rest and significant increase in CaM binding to buffers at [Ca] > 500 nM (see Fig. 3).

Model of myocyte CaM signaling during EC coupling

After validating individual modules with in vitro data, we incorporated reactions for CaM, CaMKII, CaN, and CaM buffering into a previously described and validated model of excitation-contraction coupling in the adult rabbit ventricular myocyte (7,8). This model includes calcium transport between several compartments: the dyadic cleft (site of calcium-induced calcium release), a subsarcolemmal space, cytosol, and the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) (Fig. 1 A). Total CaM was set at 6 μM (24,25), and CaM buffers (BTOT) were set to 26 μM (20 μM free + 6 μM bound). The fraction of CaM buffers in the dyad was adjusted to obtain a dyadic CaM concentration of 422 μM (0.35 μmol/L cytosol) at rest, based on one CaM bound per L-type Ca channel or ryanodine receptor (RyR) monomer (26). This estimate is consistent with calculations of ∼25 CaM molecules in the vicinity of each L-type Ca channel (27) and reflects local enrichment of CaM within this small compartment. Model predictions of dyadic cleft CaMKII or CaN signaling were affected <15% by fourfold increases or decreases in dyadic [CaM]. Results were very insensitive to varying BTOT over a 10–100 μM range. Due to limited information on subsarcolemmal CaM/CaMKII/CaN signaling, we assumed the same concentrations as in the cytosol but did not analyze this compartment in detail here.

Free CaM diffusion between subsarcolemma and cytosol was modeled using data of CaM diffusivity (28) along with geometries used by Shannon et al. to model Ca diffusion between these compartments (7). As dyadic CaM is tethered to the L-type Ca channel or RyR (26,27) and there is a separation between kinetics of CaM dissociation and free CaM diffusion of more than three orders of magnitude, we assumed reaction-limited CaM transport between dyad and subsarcolemma. Thus we modeled dyadic/sarcolemmal CaM transport using the same kinetics as in our overall CaM buffer reactions.

We estimate a total subunit [CaMKII] of 0.2 μmol/L cytosol by comparing specific activity of purified CaMKII (29,30) with total CaMKII activity in ventricular homogenates (31). We estimate a total [CaN] of 3 nmol/L cytosol by comparing specific activity of purified CaN (32) with total CaN activity in adult cardiac myocytes (33). As the quantitative distribution of CaMKII and CaN between dyadic cleft and cytosolic compartments is unknown, we use the model to test how various distributions affect their responsiveness to local Ca signals (see Figs. 5–8). Kinetic parameters were obtained from in vitro experiments at <37°C due to limited available data (CaM and CaN, 30°C; CaMKII, 0°C). However, model predictions of dyad versus cytosolic activities or CaMKII versus CaN activities were very insensitive to changes in kinetic rates reflecting average levels of parameter uncertainty (see Fig. S2 and Data S1). Based on a comparison of ventricular homogenate phosphatase 1 (PP1) activity (34,35) and specific activity of purified PP1 (36), we estimate a total cellular PP1 of 0.65 μmol/L cytosol. Based on evidence of PP1 tethering to the RyR complex (37), we assumed 1 PP1/RyR tetramer (96.5 μM in the dyad) resulting in a cytosolic concentration of 0.57 μM. Dyadic CaMKII activities were very insensitive for up to 10-fold changes in dyadic [PP1], but note the dramatic effects of eliminating PP1 tethering (see Fig. 5 C).

FIGURE 5.

Predicted local CaMKII dynamics in beating cardiac myocytes. (A) Dyadic-cleft CaMKII activity increases significantly from 1 (solid line) to 4 Hz pacing (dashed line). (B) Dyadic-cleft CaMKII-Thr287P autophosphorylation is minimal under normal conditions, unless PP1 tethering to RyR is disrupted, as seen in heart failure (37,39). (C) Cytosolic CaMKII activity remains very low at 1 and 4 Hz.

FIGURE 6.

Predicted local calcineurin dynamics in beating cardiac myocytes. (A) Even at low heart rates, any CaN in the dyadic cleft remains fully locked in an activated state due to its slow dissociation of Ca4CaM. (B) When pacing is increased from 0.5 to 4 Hz, cytosolic CaN activity slowly accumulates activity from previous beats with τ ∼ 15 min. (C) Cytosolic CaN is fairly sensitive to pacing rate, integrating dynamic Ca signals with activity somewhat higher than in response to a constant signal fixed at the mean cytosolic [Ca].

FIGURE 7.

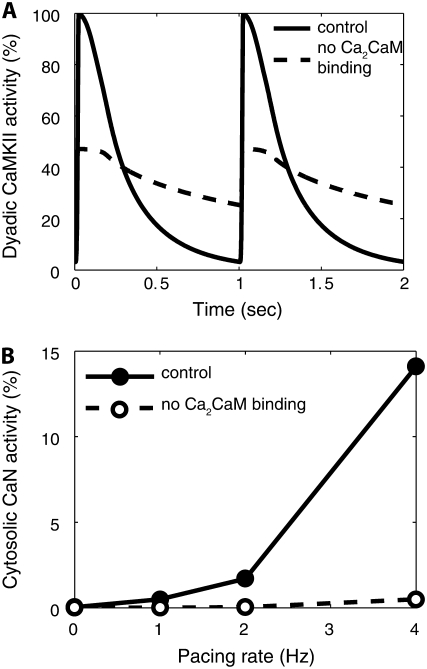

Reversing CaM affinity switches characteristic local activation patterns of CaMKII and CaN. Increasing CaMKII's affinity for Ca4CaM to that of CaN (28 pM) enhances cytosolic activity (A) yet locks dyadic-cleft CaMKII in a fully activated state. Lowering CaN's affinity for Ca4CaM to that of CaMKII (33.5 nM) allows appreciable beat-to-beat variation of CaN activity in the dyadic cleft (B) yet substantially reduces cytosolic CaN activity (C).

FIGURE 8.

Role of CaM buffering in modulating CaMKII and CaN activation. Increasing CaM availability by eliminating CaM sarcolemmal and cytosolic CaM buffers (BTOT-SL = 0, BTOT-CYT = 0) (dashed lines) is insufficient to substantially activate cytosolic CaMKII (A), but significantly enhances cytosolic CaN activity in response to pacing (B).

RESULTS

Properties of CaM, CaMKII, and CaN modules in vitro

To assess the extent to which our simple yet biochemistry-based reaction models of CaM, CaMKII, and CaN could predict measured characteristics in vitro, we compared model predictions to published experimental data independent from that used to build the model. There are no error bars in the experimental data from the literature plotted in Fig. 2, A–D, because they were not provided in the original publications. By incorporating data on how [K] and [Mg] affect the apparent Ca affinities of CaM (10,11), our two-step model of CaM activation could accurately reproduce overall Ca binding characteristics for new combinations of [Ca], [K], and [Mg] seen experimentally (11) (see Fig. 2 A), which is also broadly consistent with many other CaM studies (12,13). As noted in Methods, only the [Mg] dependence of CaM was obtained from Stemmer and Klee (11); the intrinsic Ca affinities, [K] dependence, and kinetics of CaM were obtained from other cited sources. CaM-dependent CaN regulation was modeled as reversible associations between CaM, Ca2CaM, Ca4CaM, and CaN (see Fig. 1 D). Model predictions of [Ca] versus CaN activity for 0.03–0.3 μM [CaM] (Fig. 2 B) are quite consistent with the leftward shift observed in independent experimental data with 3 nM [CaN], 140 mM [K], and 0.5 mM [Mg] (11). Although three parameters in the CaN module were obtained from Stemmer and Klee (11) (kCaN2off, kCaN4off, and kCaCaNon), these parameters were determined from experiments independent of the validation data shown in Fig. 2 B.

Using CaMKIIδ-specific parameters for Ca4CaM binding affinity and autophosphorylation rate in the model, we could also reproduce experimental relationships between [CaM] and CaM-dependent activity or Thr287-autophosphorylation-dependent CaMKII activity (6) (Fig. 2, C and D). Although our model used binding data of [CaM] with CaMKII from Gaertner et al. (6), the data shown in Fig. 2, C and D, are separate activity data from the same article. To even more stringently validate our model of CaMKIIδ activity, we examined the relationship between [Ca] and CaMKII activity for fixed [CaM]. Similar to our above validations of CaM, we found that [K] and [Mg] dependence of CaM activation was critical for validation of CaM-dependent processes with in vitro data, which are often obtained at concentrations far from in vivo settings. We could reasonably predict the relationship between [Ca] and CaM-dependent activity of CaMKIIδ at 200 mM [K] and 2 mM [Mg], as performed for CaMKIIα experimentally (20) (Fig. 2 E), by considering the known higher affinity of CaMKIIδ (6). However, physiologic ionic concentrations (135 mM [K] and 1 mM [Mg] in the model) shift the model predictions leftward significantly (not shown). We also found that the model could accurately predict both the EC50 and cooperativity in the relationship between [Ca] and CaM-independent CaMKII (Thr287-autophosphorylated) activity for 0 and 2.5 μM [PP1] seen experimentally with CaMKIIα (20) (Fig. 2 F), as these relationships have not been published for CaMKIIδ. By comparing relationships for CaM activation, CaM-dependent CaMKII activity, CaMKII autophosphorylation, and PP1-dependent CaMKII dephosphorylation in model and experiment, we show that this fairly simple yet biochemically based model of CaMKII can predict many known properties of its function in vitro to within one standard deviation (except for Fig. 2 E, noting known isoform differences) without curve-fitting to validation data sets. These tests are important for justifying subsequent simulations in which CaMKII is modeled in the context of a beating cardiac myocyte.

Model of CaM buffering in cardiac myocytes

In addition to CaN and CaMKII, CaM binds to many other proteins and is thus highly buffered. Although CaM buffering has not been studied extensively in myocytes, we developed a simple lumped model of CaM buffering constrained by recent measurements of free and bound CaM in adult myocytes (23), as described in Methods (see also Fig. 1 B). As shown in Fig. 3 A, this model could accurately reproduce binding kinetics between CaM and buffers, which is 100 times slower at 500 nM [Ca] compared with resting levels (100 nM). Note that in experiments (23), fluorescently labeled CaM was used, and our simulation uses 16 nM CaM to mimic the incomplete washout attained experimentally. Although it is currently unknown whether Ca2CaM dissociates from these buffers at the same rate as Ca4CaM, this was the rate required for the model to predict a significant shift from “slow” to “fast” dissociation from buffers during the moderate drop from 500 to 100 nM [Ca]. The model predicts a significant decrease in free [CaM] from 1% free (60 nM) to 0.3% with elevated [Ca]. This increased CaM binding is consistent with data showing significantly increased binding of fluorescently labeled CaM in permeabilized myocytes held at high [Ca] (23), suggesting that competition for CaM may become even more intense as Ca rises during the heartbeat. As steady-state [Ca] increases, the model predicts switching of buffered CaM from Ca-free CaMB states at 100 nM to Ca2CaMB at 500 nM [Ca] and Ca4CaMB at [Ca] >30 μM (see Fig. 3 B), which is somewhat more sensitive than free CaM (where switching from CaM to Ca2CaM occurs at 3 μM [Ca]).

Beat-to-beat CaM dynamics in dyadic cleft and cytosol

We incorporated the above reactions for CaM, CaMKII, CaN, and CaM buffering into a well validated model of cardiac myocyte EC coupling (7) (see Methods). At each heartbeat, voltage- and Ca-dependent Ca fluxes cause a large spike in dyadic-cleft [Ca]. Ca then diffuses to the cytosol to form the Ca transient. In response to this Ca surge, the model predicts that dyadic-cleft CaM is rapidly saturated with Ca (forming Ca4CaM). But as [Ca] drops, two Ca ions dissociate rapidly from the N-terminal EF hand (τ ∼ 19 ms) and then the remaining two Ca ions dissociate more slowly from the C-terminal EF hand (τ ∼ 157 ms) (Fig. 4 A). In contrast, cytosolic [Ca] appears insufficient for significant Ca binding to CaM, and Ca binding occurs almost exclusively as Ca2CaM which does not strongly activate CaN or CaMKII (Fig. 4 B). Upon increasing pacing frequency from 1 to 4 Hz to simulate faster heart rates, dyadic-cleft Ca4CaM is still strongly activated but does not accumulate additional baseline activity (Fig. 4 C), whereas in the cytosol, the model predicts a slight increase in activated CaM and some accumulation, but the total activity is still extremely small (Fig. 4 D). Assuming similar [CaM] and buffer between subsarcolemma and cytosol, we predict subsarcolemmal Ca4CaM signals with magnitudes between those of the dyadic cleft and the cytosol (Fig. 4 E). The very different responses of CaM in dyadic cleft and cytosol are likely to strongly affect CaM-dependent signaling pathways localized in these compartments.

FIGURE 4.

Local CaM dynamics in a model of a beating cardiac myocyte. (A) Ca2CaM and Ca4CaM are strongly activated during each beat in the dyadic cleft. (B) Only a small fraction of CaM binds Ca in the cytosol with 1 Hz pacing. Ca dissociates very rapidly from Ca4CaM and more slowly from Ca2CaM. (C) When pacing rate is increased from 1 to 4 Hz, Ca4CaM still does not accumulate in the dyadic cleft. (D) Ca4CaM only slightly accumulates activity in the cytosol. (E) Subsarcolemmal Ca4CaM signals are predicted to lie between dyadic and cytosolic [Ca4CaM].

Local dynamics of CaMKII activation

With very strong CaM signals in the dyadic cleft, at each heartbeat, CaMKII subunits are predicted to fully activate and then more slowly dissociate CaM throughout diastole (Fig. 5 A). As pacing frequency is increased from 1 to 4 Hz, dyadic-cleft CaM-dependent CaMKII activity is maintained throughout diastole, resulting in a substantial increase in mean CaMKII activity (Fig. 5 A). However, due to high local [PP1] in the dyadic cleft, Thr287 autophosphorylation of CaMKII is restricted to <1%, even at increased pacing rates (see Fig. 5 B). When PP1 tethering to the RyR is disrupted, as occurs in heart failure (37) (dyadic [PP1] reduced from 96.5 to 0.57 μM), dyadic CaMKII autophosphorylation is predicted to rise considerably (Fig. 5 B). These predictions are consistent with experimental data showing very little autophosphorylation in normal ventricular myocytes unless pacing is combined with PP1 inhibition (38), yet highly elevated CaMKII autophosphorylation in heart failure (39).

In the cytosol, the low CaM signals are insufficient to activate CaMKII, so that only 8 in 106 subunits activate even at 4 Hz (Fig. 5 C). Unlike CaN (see Fig. 6 B), in all simulations, CaMKII kinetics achieved the steady states shown within seconds. Thus, in the dyadic cleft, CaMKII is quite responsive to local Ca signals and exhibits frequency-dependent activity but little autophosphorylation, whereas in the cytosol the limited Ca-CaM appears insufficient for CaMKII activity.

Local dynamics of calcineurin activation

Compared with CaMKII, CaN has a much higher affinity for CaM, and this appears to have a great impact on its response to local Ca signals. In model simulations, CaN in the dyadic cleft remained locked in a fully activated state as it did not dissociate from CaM between heartbeats (Fig. 6 A). In the cytosol, its high affinity for CaM allows it to better compete for the very small free CaM pool. In contrast to the rapid responses of CaMKII (Fig. 5), CaN exhibited gradual responses to changes in heart rate from 1 to 4 Hz (τ ∼ 2 min) (Fig. 6 B). Steady-state cytosolic CaN activity increases with increasing pacing rates (Fig. 6 C). As shown in Fig. 6 C (lower dashed line), the CaN response to oscillating Ca signals is similar to the response to a constant Ca signal fixed at the mean [Ca]i for that pacing rate (not the peak). Thus, dyadic-cleft CaN is predicted to be maximally active but unresponsive to altered Ca signals, whereas cytosolic CaN exhibits gradual increases in activity in response to increased pacing rates.

CaM affinity determines differential local CaMKII and CaN activities

Why do predictions of CaMKII and CaN differ so greatly? One answer could be their different activation mechanisms. CaN requires Ca before CaM association and can bind Ca-free CaM. In contrast, CaMKII binds only Ca2CaM or Ca4CaM and exhibits autophosphorylation. We hypothesized that although the specific reaction mechanisms for CaMKII and CaN activation differ, their different affinities for Ca4CaM could substantially explain their predicted divergent responses to local Ca signals. To test this hypothesis in the model, we perturbed the rate constants of CaN and CaMKII for Ca4CaM to switch their CaM affinities: CaN from Kd 0.028–33.5 nM, and CaMKII from Kd 33.5–0.028 nM. Switching CaMKII from a low- to a high-affinity CaM target increased cytosolic activity (Fig. 7 A) and locked dyadic-cleft CaMKII in a maximally activated state (not shown). Switching CaN from a high- to a low-affinity CaM target allowed dyadic-cleft CaN to vary significantly from beat to beat, at the same time retaining strong activity (Fig. 7 B), whereas cytosolic CaN activity diminished considerably (Fig. 7 C). Overall, switching CaM affinities of CaMKII and CaN substantially switched their functional responses to local Ca signals, demonstrating that CaM affinity is a strong determinant of response to local Ca.

Role of CaM availability on CaMKII and CaN activation

To better understand the role of CaM buffering on selective CaMKII and CaN activation, we performed simulations in which CaM buffering was removed (i.e., free CaM was set to 6 μM and all CaM was available to interact with CaMKII and CaN). Even with sarcolemmal (SL) and cytosolic CaM buffers removed (BTOT-SL = 0, BTOT-CYT = 0), <0.01% of cytosolic CaMKII subunits were activated during pacing (Fig. 8 A). Removing CaM buffering elevated CaN activity at all pacing rates (Fig. 8 B). These model results suggest that the low [Ca] and [Ca4CaM] in the cytosol are insufficient for robust cytosolic CaMKII activation, even in conditions with enhanced CaM availability. In contrast, low CaM availability puts a significant brake on cytosolic CaN activity, which may prevent constitutive CaN activity at resting heart rates for rabbit.

Role of Ca and Ca2CaM dissociation from Ca-CaM-target complexes

In addition to deactivation by Ca4CaM dissociation, both CaMKII and CaN models include reactions for reversible dissociation of two Ca from the Ca4CaM-target complex and subsequent dissociation of Ca2CaM from each target, based on prior biochemical studies (11,18,19). To examine the significance of these reactions in the cellular context, we ran additional simulations in which only Ca4CaM (and not Ca2CaM) could bind to CaMKII and CaN. With Ca4CaM dissociation as the only available deactivation pathway, CaMKII (Fig. 9 A) and CaN deactivation slowed considerably, indicating that Ca dissociation from target-associated Ca4CaM is the dominant form of deactivation for both CaM targets. Furthermore, with Ca4CaM association as the only activation pathway, dyadic CaMKII activity was partially reduced (Fig. 9 A) and cytosolic CaN activity was greatly diminished (Fig. 9 B). This indicates that Ca2CaM binding to targets, with subsequent recruitment of Ca to form Ca4CaM-target complexes, may be the favored activation pathway in compartments with limited CaM. This occurred despite little activity of the Ca2CaM-target complex itself and significantly greater affinity of CaMKII and CaN for Ca4CaM than for Ca2CaM, because cytosolic [Ca2CaM] far exceeded cytosolic [Ca4CaM] (see Fig. 4 B).

FIGURE 9.

Role of Ca2CaM binding in modulating CaMKII and CaN activation. (A) Eliminating binding reactions between Ca2CaM and CaMKII reduced peak dyadic-cleft CaMKII activity and slowed inactivation, leaving mean activity relatively unaffected at 1 Hz. (B) Eliminating Ca2CaM binding substantially suppressed cytosolic CaN activity.

DISCUSSION

It is currently unclear how Ca-dependent signaling pathways in the heart are selectively regulated. Furthermore, the local Ca signals relevant to key Ca-dependent pathways such as CaMKII and CaN have not been identified (2). Here, we developed what we believe is a novel computational model of the ventricular myocyte to investigate molecular mechanisms of differential spatial and temporal control of CaM, CaMKII, and CaN activities that may underlie selective pathway activation.

CaM dynamics in ventricular myocytes

Due to intense competition between CaM targets, CaM has been described as a limiting factor to cell signaling (3). Free CaM is only ∼1% of total CaM in resting adult ventricular myocytes (23) and smooth muscle (40,41), and our model of CaM buffering predicts that competition for CaM becomes even more intense as [Ca] rises. Using a biosensor for Ca-CaM expressed in adult ventricular myocytes, Maier et al. found measurable beat-to-beat Ca-CaM oscillations only when overexpressing CaM (25). This is consistent with our prediction that cytosolic Ca-CaM oscillations with normal CaM levels are very small, likely below the threshold of detection by low-affinity Ca-CaM sensors.

Our model predictions are consistent with these prior studies and provide additional mechanistic insight. In the cytosol, simulations indicated that limited beat-to-beat activation of Ca-CaM was due not only to limited free CaM (∼1% of total CaM) but also to limited activation of free CaM by cytosolic Ca (∼0.5% of free CaM) due to its high apparent Kd (10 μM) compared with cytosolic [Ca]. A directly testable model prediction is that sustained very high [Ca] should activate the CaM biosensor much more strongly than seen previously with beat-to-beat electrical pacing. In contrast, the dyadic cleft can exhibit much higher local [Ca] (>50 μM) than the cytosol, and CaM is highly enriched in this microdomain (26,27), both important for the model's predictions of robust activation of dyadic Ca-CaM. The significance of faster off-rates of Ca from the N-terminal versus the C-terminal EF hands of CaM (13) can be observed in the predicted lack of accumulation of dyadic-cleft Ca4CaM even at high heart rates. However, bound Ca4CaM may accumulate on high-affinity CaM targets (such as CaM buffers or CaN) to allow integration, as observed with fluorescent CaM biosensors during isoproterenol exposure (25) or increased pacing rate (42).

Local CaMKII activity

CaMKIIδ regulates many important cardiac processes, including EC coupling (43,44), apoptosis (45), and transcription (46). CaMKIIδC is often referred to as the cytosolic isoform, because it is excluded from the nucleus compared with the δB isoform (47). Although CaMKII has substrates in both dyadic cleft (L-type Ca2+ channel, RyR) (44,48) and cytosol (phospholamban) (49), and immunoprecipitates with the L-type Ca channel (48) and RyR (50), the quantitative distribution of CaMKIIδC among extranuclear compartments is unknown. The local Ca signals regulating CaMKIIδC are also unknown. Despite the label “cytosolic”, our model predicts that CaMKIIδC is quite insensitive to cytosolic Ca signals due to limited cytosolic Ca-CaM and a relatively low affinity of CaMKII for CaM. In contrast, the model predicts robust beat-to-beat oscillations in CaMKII activity in the dyadic cleft due to the large local [Ca] and CaM enrichment. As suggested by biochemical studies (19), deactivation kinetics for these oscillations were dominated by Ca dissociation from the Ca-CaM-CaMKII complex rather than classical Ca4CaM dissociation.

In addition to regulating EC coupling, CaMKII selectively regulates hypertrophic gene transcription, yet the mechanism for selective regulation of contractility versus transcription has not been identified (2). If, as predicted by the model, CaMKII regulation requires subcellular targeting to domains with high local [Ca], this could potentially explain how CaMKII tethered to nuclear IP3 receptors can respond to IP3-mediated Ca release yet be insensitive to beat-to-beat Ca oscillations (46). However, a requirement for high local [Ca] also raises new questions, as it becomes unclear how cytosolic CaMKII substrates distant from the dyadic cleft (e.g., phospholamban) may be regulated. In neurons, CaM-bound CaMKII translocates to postsynaptic densities (51), yet CaMKII translocation has not been reported in cardiac myocytes.

Frequency-dependent CaMKII activity contributes to L-type Ca2+ channel facilitation (52), frequency-dependent acceleration of relaxation (53), and possibly the positive force-frequency relationship (54). As heart rate increases in our model, dyadic cleft CaMKII activity rises significantly, with a “memory” of ∼1 s, which is consistent with reported rates of CaMKII-dependent, frequency-dependent acceleration of relaxation (38) and L-type Ca2+ channel facilitation (52) (<5 s), but faster than the time courses for RyR or phospholamban phosphorylation (∼3 min) (38). Frequency-dependent activity was dictated by the rate of Ca dissociation from Ca4CaM/CaMKII rather than the magnitude of the Ca signal or Thr287 autophosphorylation.

CaMKII autophosphorylation is prominent in many cell types, often correlates with overall CaMKII activity (15), and can lead to enhanced “memory” or bistability (55). In the heart, however, the precise conditions that trigger CaMKII autophosphoryation, and its physiologic significance, are still under debate (38,56). In our model, dyadic cleft Thr287 autophosphorylation was minimal under normal conditions, consistent with recent experimental data (38), yet when RyR/PP1 preassociation was disrupted, as reportedly occurs in heart failure (37), dyadic CaMKII autophosphorylation was seen to rise dramatically, as seen with heart failure (39) or PP1 inhibition (38). It appears that CaMKII may exhibit significant autophosphorylation only in pathophysiologic conditions, where local [PP1] is depleted. Thus, CaMKII appears responsive only to high [Ca] signals, as are found in the dyadic cleft, and exhibits frequency-dependent activity relevant to the range of physiologic heart rates, despite minimal autophosphorylation.

Local CaN activity

Calcineurin plays an important role in cardiac hypertrophy via dephosphorylation of the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), and it dephosphorylates several additional substrates in cardiac myocytes (57). CaN docks with several protein complexes, including the L-type Ca channel (58), neonatal but not adult RyR2 (37,59), and sarcomeric calsarcin (60), but may also translocate to the nucleus along with NFAT (61). However, quantitative subcellular distribution of CaN in adult myocytes is unknown, and the local Ca signals responsible for its regulation have not been identified for the heart (1,2). Here, we found evidence that due to the high affinity of CaN for Ca4CaM, CaN may effectively compete for the limited cytosolic CaM pool (unlike CaMKII). Cytosolic CaN was responsive to increased pacing frequency, consistent with data from atrial myocytes (62), and this response was greatly amplified when CaM buffering was removed. In response to changes in pacing rate, CaN activity reflected an integration of past Ca signals with τ ∼ 3 min. Blocking Ca2CaM binding to CaN significantly dampened CaN activity, indicating that this is likely the dominant CaN activation pathway in CaM-limited compartments like the cytosol. These findings support the hypothesis that the CaN-NFAT signaling pathway may be responsive to subtle changes in cytosolic Ca signals.

At the dyadic cleft, the high [Ca] signals and very slow dissociation of Ca4CaM/CaN resulted in constitutively active CaN even with very low pacing frequencies. Thus, CaN targeted to such Ca release sites is unlikely to participate in the CaN-NFAT hypertrophic signaling axis (unless Ca-CaM-CaN can translocate without losing CaM). CaN may act very differently in different compartments, for example, as a constitutively active phosphatase in regions of high [Ca], and as a sensitive integrator of Ca signals in regions of low [Ca]. Although CaN translocation has not been observed in cardiac myocytes, nor is it modeled here, our predicted slow inactivation of Ca4CaM/CaN indicates that CaN potentially translocating from the dyadic cleft or cytosol may retain activity for some time, as in other cell types (61).

Role of CaM affinity and availability

CaM-binding proteins exhibit a wide range of affinities, and limited CaM availability may allow CaM affinity to sensitively affect when and where CaM targets are activated (3). Alternatively, the different activation mechanisms of CaMKII and CaN may underlie their different responses. We found that by switching the CaM affinities of CaMKII and CaN, we could essentially reverse their characteristic responses to local Ca signals in cardiac myocytes. This demonstrates that CaM affinity is a major determinant of selective responsiveness in these cells. Tentatively extrapolating to other CaM targets, we could predict the local Ca signals relevant to targets such as phosphodiesterase, nitric oxide synthase, and adenylyl cyclase based on their known CaM affinities. Although systematically altering the CaM affinity of endogenous proteins is difficult in practice, initial experiments comparing fluorescent CaM biosensors of high and low CaM affinity (similar to CaN and CaMKII) indicate different frequency-dependent Ca-CaM responses in adult myocytes (42). Further experiments such as this one will provide opportunities to directly validate our model predictions.

We found that whereas cytosolic CaMKII could not be highly activated, even with additional CaM, removing CaM buffers substantially amplified cytosolic CaN activity. This prediction is consistent with experimentally measured beat-to-beat changes in cytosolic fluorescent CaM biosensors found only when they are overexpressing CaM (25,42), and could be further validated in future studies by testing whether CaN-NFAT activity is more sensitive when CaM is overexpressed. Thus, CaM buffering (23) may modulate CaN and other Ca signaling pathways, and altered expression of CaM or CaM-binding proteins during cardiac disease could potentially remodel how CaM selectively regulates contractility and gene transcription.

Limitations

With any mechanistic model built using parameters from the biochemical literature, one can only reasonably include known mechanisms, and uncertainty in parameter values is unavoidable. However, these models can integrate known molecular mechanisms into a consistent quantitative framework and can demonstrate their sufficiency, and discrepancies between model and experiment can be used to identify new mechanisms necessary to explain a phenotype. Only limited information is available for CaM buffers, and each of these buffers may interact with CaM differently. However, the average CaM buffering behavior should be well represented by the experimental data used to develop our model (23). Although subcellular CaM distribution is not fully characterized, we found that a 16-fold variation in dyadic [CaM] affected results by <15%, and results were similar in the cytosol.

We have not modeled CaMKII or CaN diffusion due to a lack of experimental data to support such transport in myocytes. Immunofluorescence data indicate sarcolemmal or Z-line localization of CaMKII and CaN (63,64), suggesting that CaMKII and CaN are primarily fixed. However, given our model predictions of CaMKII and CaN kinetics, we can anticipate the impact of CaMKII/CaN diffusion should it occur. Dyadic CaMKII inactivated rapidly under normal conditions, which would minimize its ability to activate cytosolic targets unless autophosphorylated (which slowed inactivation). In contrast, CaN inactivated slowly, which may allow transfer of the CaN signal from the dyad to the cytosol/nucleus should dyadic CaN translocate. Indeed, CaN has been reported to detect local Ca signals at neuronal Ca channels (58) and also to translocate to the nucleus with NFAT (61) in other cell types.

Here, we have only focused on differences in signaling between the dyadic-cleft and cytosolic compartments, yet many other subcellular domains are likely to contain localized CaM signaling. For example, subsarcolemmal CaM signaling (including interactions with the sarcolemmal Ca pump, IKs, and NO synthase) would be expected to be between the extremes of cleft- and cytosolic-domains CaM signaling that we have focused on here. However, we have not explored this in detail, because of limited available data for CaM in this domain. We also have not included nuclear CaMKII signaling at the IP3 receptor (46) or stochastic reactions occurring within individual protein complexes. Our compartmental model does not account for cytosolic tethering of Ca-free CaM near Ca4CaM targets by proteins such as neuromodulin that are thought to provide local CaM stores in neurons (65). Lack of detailed information about pretethering of CaM to specific Ca4CaM targets may affect our predictions of limited CaM activation and binding of Ca4CaM targets in the cytosol. However, our simulations with enhanced CaM availability (Fig. 8) provide a quantitative indication of how tethering may enhance such interactions. We have focused on only two CaM targets, CaMKII and CaN, because they exhibit different CaM affinities and regulate a diverse set of important cardiac functions. Future study will be required both to understand how other endogenous CaM targets (e.g., RyR, NO synthase, and IKs) are modulated locally and how these local signaling pathways coordinate their downstream physiological responses (e.g., apoptosis, contractility, NFAT, or HDAC-dependent transcription). Our model of CaM buffers implicitly incorporates the competition for CaM between these unmodeled CaM targets, CaMKII and CaN. Because our intention was to focus on the molecular mechanisms of CaMKII and CaN activation, we have not modeled the feedback of CaMKII activity on Ca channels and pumps, as others have done with simpler CaM models (54,66). Our new work can now be integrated with such modeling, including CaMKII-dependent effects on cardiac ion channels (67), to better understand the molecular basis of CaMKII-mediated arrhythmias and related physiology.

We limited our studies to compartmental deterministic simulations both for simplicity and because such simulations are computationally feasible for up to 1 h, which is well beyond the timescale of published stochastic myocyte models (68,69). A single dyad contains <100 CaM, CaMKII, or CaN molecules, which may provide for stochastic variability in signaling. Stochasticity has been predicted not only to generate “noise”, but also to qualitatively affect feedback systems, including Ca-induced Ca release in the cardiac myocyte dyad (68,70). Although CaN does not exhibit positive feedback, CaMKII's autophosphorylation may be sensitive to stochastic effects. Bhalla compared stochastic and deterministic simulations of CaMKII at abundances comparable to our dyadic-cleft model (70). He found that CaMKII autophosphorylation exhibited significant noise, but that CaM-dependent CaMKII activity was very similar to deterministic simulations. Our simulations predict little CaMKII autophosphorylation due to high local [PP1] in the dyad, so we expect that stochasticity may not qualitatively affect whole-cell behavior, except in cases of PP1 inhibition (like heart failure). Although we have not incorporated CaMKII regulation of ICa or RyR, these create additional positive feedbacks which may be sensitive to stochasticity

Despite inescapable limitations, our computational model predicts a variety of key features of Ca-dependent signaling in a manner consistent with the existing independent experimental data. Furthermore, the model provides what we believe are novel predictions that highlight the crucial role of CaM affinity and localization in modulating CaMKII and CaN activity in cardiac myocytes. These model predictions are directly testable experimentally, with the recent availability of fluorescent reporters for CaM binding (25), CaN activity (71), and CaMKII activity (72). Additional molecular mechanisms can be systematically integrated with our model as needed.

In conclusion, we developed a computational model that provides mechanistic insight into the local Ca signals relevant to CaMKII and CaN pathways in cardiac myocytes, and into how CaM mediates the differential regulation of these pathways in the dyadic cleft and cytosol. CaMKII appears to be effective only in the dyadic cleft, is frequency-dependent, shows little autophosphorylation under normal conditions, and exhibits little memory (fewer than five heartbeats). In contrast, CaN appears to be responsive to time-varying Ca signals only in the cytosol, where its activity reflects the integrated cytosolic Ca signal over several minutes. CaM affinity and availability are primary determinants for the divergent responses of CaN and CaMKII to local Ca, and these mechanisms may allow selective activation of Ca pathways regulating beat-to-beat contractility (CaMKII) and cardiac hypertrophy (CaN).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view all of the supplemental files associated with this article, visit www.biophysj.org.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Eleonora Grandi and Fei Wang for their help in the implementation of the excitation-contraction coupling model.

This work was supported by grants from the University of Virginia (J.S.), the American Heart Association (0830470N to J.S.), and the National Institutes of Health (HL30077 and HL80101 to D.B.)

APPENDIX

Tables 1–3 provide reaction parameters, along with a note of whether that parameter was direct (*), derived (†, as described in Methods), or estimated (‡) from cited sources. No curve-fitting was used. Each of the below CaM, CaMKII, and CaN reactions were included in dyadic cleft, sarcolemmal, and cytosolic compartments, with compartment-specific total concentrations as specified in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Protein total concentrations

| Parameter | Value | Units | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| CaMTOT | 6.0 | μM | (24,25)* |

| BTOT-CYT | 24.5 | μM | (23)‡ |

| BTOT-SL | BTOT-CYT | μM | — |

| BTOT-DYAD | 1.86 | mM | (26,27)†‡ |

| CaMKIITOT-CYT | 0.2 (0 by default) | μM | (29–31)† |

| CaMKIITOT-SL | CaMKIITOT-CYT | μM | — |

| CaMKIITOT-DYAD | 120 | μM | (29–31)‡ |

| CaNTOT-CYT | 3e-3 | μM | (32,33)† |

| CaNTOT-SL | CaNTOT-CYT | μM | — |

| CaNTOT-DYAD | 3.62 (0 by default) | μM | (32,33)† |

| PP1TOT-CYT | 0.57 | μM | (34,35)† |

| PP1TOT-SL | PP1TOT-CYT | μM | — |

| PP1TOT-DYAD | 96.5 | μM | (37)‡ |

Parameters are direct (*), derived (†), or estimated (‡) from cited sources.

CaM reaction fluxes

Reaction fluxes, in units of [μM s−1], for reactions of Ca binding to CaM are as shown in Fig. 1, A and D, and described in Methods. Parameter values are listed in Table 1.

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

|

(8) |

Ca binding to CaM and CaM buffering

Differential equations (units in [μM ms−1]) for concentrations of free CaM, Ca2CaM, and Ca4CaM, computed separately for each compartment (dyadic cleft, sarcolemma, and cytosol). In addition, CaM, Ca2CaM, and Ca4CaM have transport fluxes as follows:

|

(9) |

|

(10) |

|

(11) |

|

(12) |

|

(13) |

|

(14) |

|

(15) |

CaM transport

Transport fluxes for reaction-limited transport of CaM between dyad and sarcolemma, and free diffusion between sarcolemma and cytosol, are as shown in Fig. 1 A and described in Methods. Dyad-SL transport fluxes are in units of [μmol/(L dyad) s−1], which requires a VDYAD/VSL conversion for computing SL concentrations. SL-cytosol fluxes are in units of [μmol s−1], requiring division by VSL or VCYT for the corresponding compartments. Volumes are from Shannon et al.: VDYAD = 1.79 × 10−14 L; VSL = 6.60 × 10−13 L; and VCYT = 2.14 × 10−11 L (7). We estimate that kSLCYT = 8.59 × 10−12 L s−1 based on diffusivity of free CaM (28) and myocyte geometry (7).

|

(16) |

|

(17) |

|

(18) |

|

(19) |

|

(20) |

|

(21) |

CaMKII activation

Six state model of CaMKII activation, as described in Methods. Px are probabilities ranging from 0 to 1 of a given CaMKII subunit being in a given state (I, B2, B, T, T2, or A), where the total concentration of subunits in state ‘X’ is Px *[CaMKIITOT]. Differential equations are in units of [msec−1]. Parameters listed in Table 2.

|

(22) |

|

(23) |

|

(24) |

|

(25) |

|

(26) |

|

(27) |

|

(28) |

|

(29) |

|

(30) |

|

(31) |

|

(32) |

|

(33) |

|

(34) |

|

(35) |

|

(36) |

|

(37) |

|

(38) |

Calcineurin activation

Model of Ca and CaM binding to CaN, as described in Methods. Parameters listed in Table 3. Differential equation in units of [μM ms−1].

|

(39) |

|

(40) |

|

(41) |

|

(42) |

|

(43) |

|

(44) |

|

(45) |

|

(46) |

|

(47) |

|

(48) |

|

(49) |

Editor: Michael D. Stern.

References

- 1.Bush, E. W., D. B. Hood, P. J. Papst, J. A. Chapo, W. Minobe, M. R. Bristow, E. N. Olson, and T. A. McKinsey. 2006. Canonical transient receptor potential channels promote cardiomyocyte hypertrophy through activation of calcineurin signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 281:33487–33496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Molkentin, J. D. 2006. Dichotomy of Ca2+ in the heart: contraction versus intracellular signaling. J. Clin. Invest. 116:623–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Persechini, A., and P. M. Stemmer. 2002. Calmodulin is a limiting factor in the cell. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 12:32–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berridge, M. J. 2006. Calcium microdomains: organization and function. Cell Calcium. 40:405–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quintana, A. R., D. Wang, J. E. Forbes, and M. N. Waxham. 2005. Kinetics of calmodulin binding to calcineurin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 334:674–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaertner, T. R., S. J. Kolodziej, D. Wang, R. Kobayashi, J. M. Koomen, J. K. Stoops, and M. N. Waxham. 2004. Comparative analyses of the three-dimensional structures and enzymatic properties of α, β, γ, and δ isoforms of Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J. Biol. Chem. 279:12484–12494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shannon, T. R., F. Wang, J. Puglisi, C. Weber, and D. M. Bers. 2004. A mathematical treatment of integrated Ca dynamics within the ventricular myocyte. Biophys. J. 87:3351–3371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shannon, T. R., F. Wang, and D. M. Bers. 2005. Regulation of cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca release by luminal [Ca] and altered gating assessed with a mathematical model. Biophys. J. 89:4096–4110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qian, H. 2007. Phosphorylation energy hypothesis: open chemical systems and their biological functions. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 58:113–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linse, S., A. Helmersson, and S. Forsén. 1991. Calcium binding to calmodulin and its globular domains. J. Biol. Chem. 266:8050–8054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stemmer, P. M., and C. B. Klee. 1994. Dual calcium ion regulation of calcineurin by calmodulin and calcineurin B. Biochemistry. 33:6859–6866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haiech, J., C. B. Klee, and J. G. Demaille. 1981. Effects of cations on affinity of calmodulin for calcium: ordered binding of calcium ions allows the specific activation of calmodulin-stimulated enzymes. Biochemistry. 20:3890–3897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klee, C. B. 1988. Interaction of calmodulin with Ca2+ and target proteins. In Calmodulin. P. Cohen and C. B. Klee, editors. Elsevier, New York. 35–56.

- 14.Black, D. J., J. Leonard, and A. Persechini. 2006. Biphasic Ca2+-dependent switching in a calmodulin-IQ domain complex. Biochemistry. 45:6987–6995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hudmon, A., and H. Schulman. 2002. Structure-function of the multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochem. J. 364:593–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer, T., P. I. Hanson, L. Stryer, and H. Schulman. 1992. Calmodulin trapping by calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Science. 256:1199–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dupont, G., G. Houart, and P. De Koninck. 2003. Sensitivity of CaM kinase II to the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations: a simple model. Cell Calcium. 34:485–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shifman, J. M., M. H. Choi, S. Mihalas, S. L. Mayo, and M. B. Kennedy. 2006. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) is activated by calmodulin with two bound calciums. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:13968–13973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaertner, T. R., J. A. Putkey, and M. N. Waxham. 2004. RC3/neurogranin and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II produce opposing effects on the affinity of calmodulin for calcium. J. Biol. Chem. 279:39374–39382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradshaw, J. M., Y. Kubota, T. Meyer, and H. Schulman. 2003. An ultrasensitive Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-protein phosphatase 1 switch facilitates specificity in postsynaptic calcium signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:10512–10517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hubbard, M. J., and C. B. Klee. 1987. Calmodulin binding by calcineurin. Ligand-induced renaturation of protein immobilized on nitrocellulose. J. Biol. Chem. 262:15062–15070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang, S. A., and C. B. Klee. 2000. Low affinity Ca2+-binding sites of calcineurin B mediate conformational changes in calcineurin A. Biochemistry. 39:16147–16154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu, X., and D. M. Bers. 2007. Free and bound intracellular calmodulin measurements in cardiac myocytes. Cell Calcium. 41:353–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fabiato, A. 1983. Calcium-induced release of calcium from the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Am. J. Physiol. 245:C1–C14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maier, L. S., M. T. Ziolo, J. Bossuyt, A. Persechini, R. Mestril, and D. M. Bers. 2006. Dynamic changes in free Ca-calmodulin levels in adult cardiac myocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 41:451–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balshaw, D. M., L. Xu, N. Yamaguchi, D. A. Pasek, and G. Meissner. 2001. Calmodulin binding and inhibition of cardiac muscle calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor). J. Biol. Chem. 276:20144–20153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mori, M. X., M. G. Erickson, and D. T. Yue. 2004. Functional stoichiometry and local enrichment of calmodulin interacting with Ca2+ channels. Science. 304:432–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luby-Phelps, K., M. Hori, J. M. Phelps, and D. Won. 1995. Ca2+-regulated dynamic compartmentalization of calmodulin in living smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 270:21532–21538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanson, P. I., and H. Schulman. 1992. Inhibitory autophosphorylation of multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase analyzed by site-directed mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 267:17216–17224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sivakumaran, S., S. Hariharaputran, J. Mishra, and U. S. Bhalla. 2003. The Database of Quantitative Cellular Signaling: management and analysis of chemical kinetic models of signaling networks. Bioinformatics. 19:408–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirchhefer, U., W. Schmitz, H. Scholz, and J. Neumann. 1999. Activity of cAMP-dependent protein kinase and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase in failing and nonfailing human hearts. Cardiovasc. Res. 42:254–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsui, H., C. J. Pallen, A. M. Adachi, J. H. Wang, and P. H. Lam. 1985. Demonstration of different metal ion-induced calcineurin conformations using a monoclonal antibody. J. Biol. Chem. 260:4174–4179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.duBell, W. H., S. T. Gaa, W. J. Lederer, and T. B. Rogers. 1998. Independent inhibition of calcineurin and K+ currents by the immunosuppressant FK-506 in rat ventricle. Am. J. Physiol. 275:H2041–H2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacDougall, L. K., L. R. Jones, and P. Cohen. 1991. Identification of the major protein phosphatases in mammalian cardiac muscle which dephosphorylate phospholamban. Eur. J. Biochem. 196:725–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carr, A. N., A. G. Schmidt, Y. Suzuki, F. del Monte, Y. Sato, C. Lanner, K. Breeden, S. L. Jing, P. B. Allen, P. Greengard, A. Yatani, B. D. Hoit, I. L. Grupp, R. J. Hajjar, A. A. DePaoli-Roach, and E. G. Kranias. 2002. Type 1 phosphatase, a negative regulator of cardiac function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:4124–4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stralfors, P., A. Hiraga, and P. Cohen. 1985. The protein phosphatases involved in cellular regulation. Purification and characterisation of the glycogen-bound form of protein phosphatase-1 from rabbit skeletal muscle. Eur. J. Biochem. 149:295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marx, S. O., S. Reiken, Y. Hisamatsu, T. Jayaraman, D. Burkhoff, N. Rosemblit, and A. R. Marks. 2000. PKA phosphorylation dissociates FKBP12.6 from the calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor): defective regulation in failing hearts. Cell. 101:365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huke, S., and D. M. Bers. 2007. Temporal dissociation of frequency-dependent acceleration of relaxation and protein phosphorylation by CaMKII. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 42:590–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ai, X., J. W. Curran, T. R. Shannon, D. M. Bers, and S. M. Pogwizd. 2005. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase modulates cardiac ryanodine receptor phosphorylation and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak in heart failure. Circ. Res. 97:1314–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zimmermann, B., A. V. Somlyo, G. C. Ellis-Davies, J. H. Kaplan, and A. P. Somlyo. 1995. Kinetics of prephosphorylation reactions and myosin light chain phosphorylation in smooth muscle. Flash photolysis studies with caged calcium and caged ATP. J. Biol. Chem. 270:23966–23974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tansey, M. G., K. Luby-Phelps, K. E. Kamm, and J. T. Stull. 1994. Ca2+-dependent phosphorylation of myosin light chain kinase decreases the Ca2+ sensitivity of light chain phosphorylation within smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 269:9912–9920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song, Q., J. Bossuyt, J. Saucerman, and D. Bers. 2007. Dynamic FRET-based Ca-calmodulin measurements in intact ventricular myocytes uncover differential signal integration due to Ca-Calmodulin affinity. Circulation. 116:II–155. (Abstr.) [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li, L., H. Satoh, K. S. Ginsburg, and D. M. Bers. 1997. The effect of Ca(2+)-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II on cardiac excitation-contraction coupling in ferret ventricular myocytes. J. Physiol. 501:17–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wehrens, X. H., S. E. Lehnart, S. R. Reiken, and A. R. Marks. 2004. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II phosphorylation regulates the cardiac ryanodine receptor. Circ. Res. 94:e61–e70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu, W. Z., S. Q. Wang, K. Chakir, D. Yang, T. Zhang, J. H. Brown, E. Devic, B. K. Kobilka, H. Cheng, and R. P. Xiao. 2003. Linkage of β1-adrenergic stimulation to apoptotic heart cell death through protein kinase A-independent activation of Ca2+/calmodulin kinase II. J. Clin. Invest. 111:617–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu, X., T. Zhang, J. Bossuyt, X. Li, T. A. McKinsey, J. R. Dedman, E. N. Olson, J. Chen, J. H. Brown, and D. M. Bers. 2006. Local InsP3-dependent perinuclear Ca2+ signaling in cardiac myocyte excitation-transcription coupling. J. Clin. Invest. 116:675–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Edman, C. F., and H. Schulman. 1994. Identification and characterization of δB-CaM kinase and δC-CaM kinase from rat heart, two new multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase isoforms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1221:89–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hudmon, A., H. Schulman, J. Kim, J. M. Maltez, R. W. Tsien, and G. S. Pitt. 2005. CaMKII tethers to L-type Ca2+ channels, establishing a local and dedicated integrator of Ca2+ signals for facilitation. J. Cell Biol. 171:537–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maier, L. S., and D. M. Bers. 2007. Role of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) in excitation-contraction coupling in the heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 73:631–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang, T., L. S. Maier, N. D. Dalton, S. Miyamoto, J. Ross Jr., D. M. Bers, and J. H. Brown. 2003. The δC isoform of CaMKII is activated in cardiac hypertrophy and induces dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Circ. Res. 92:912–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shen, K., and T. Meyer. 1999. Dynamic control of CaMKII translocation and localization in hippocampal neurons by NMDA receptor stimulation. Science. 284:162–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yuan, W., and D. M. Bers. 1994. Ca-dependent facilitation of cardiac Ca current is due to Ca-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Am. J. Physiol. 267:H982–H993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bassani, R. A., A. Mattiazzi, and D. M. Bers. 1995. CaMKII is responsible for activity-dependent acceleration of relaxation in rat ventricular myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 268:H703–H712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hund, T. J., and Y. Rudy. 2004. Rate dependence and regulation of action potential and calcium transient in a canine cardiac ventricular cell model. Circulation. 110:3168–3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhabotinsky, A. M. 2000. Bistability in the Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase-phosphatase system. Biophys. J. 79:2211–2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anderson, M. E. 2005. Calmodulin kinase signaling in heart: an intriguing candidate target for therapy of myocardial dysfunction and arrhythmias. Pharmacol. Ther. 106:39–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vega, R. B., R. Bassel-Duby, and E. N. Olson. 2003. Control of cardiac growth and function by calcineurin signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 278:36981–36984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oliveria, S. F., M. L. Dell'Acqua, and W. A. Sather. 2007. AKAP79/150 anchoring of calcineurin controls neuronal L-type Ca2+ channel activity and nuclear signaling. Neuron. 55:261–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pare, G. C., A. L. Bauman, M. McHenry, J. J. Michel, K. L. Dodge-Kafka, and M. S. Kapiloff. 2005. The mAKAP complex participates in the induction of cardiac myocyte hypertrophy by adrenergic receptor signaling. J. Cell Sci. 118:5637–5646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Frey, N., J. A. Richardson, and E. N. Olson. 2000. Calsarcins, a novel family of sarcomeric calcineurin-binding proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:14632–14637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shibasaki, F., E. R. Price, D. Milan, and F. McKeon. 1996. Role of kinases and the phosphatase calcineurin in the nuclear shuttling of transcription factor NF-AT4. Nature. 382:370–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tavi, P., S. Pikkarainen, J. Ronkainen, P. Niemela, M. Ilves, M. Weckstrom, O. Vuolteenaho, J. Bruton, H. Westerblad, and H. Ruskoaho. 2004. Pacing-induced calcineurin activation controls cardiac Ca2+ signalling and gene expression. J. Physiol. 554:309–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Faul, C., A. Dhume, A. D. Schecter, and P. Mundel. 2007. Protein kinase A, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II, and calcineurin regulate the intracellular trafficking of myopodin between the Z-disc and the nucleus of cardiac myocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:8215–8227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Santana, L. F., E. G. Chase, V. S. Votaw, M. T. Nelson, and R. Greven. 2002. Functional coupling of calcineurin and protein kinase A in mouse ventricular myocytes. J. Physiol. 544:57–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu, Y. C., and D. R. Storm. 1990. Regulation of free calmodulin levels by neuromodulin: neuron growth and regeneration. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 11:107–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Livshitz, L. M., and Y. Rudy. 2007. Regulation of Ca2+ and electrical alternans in cardiac myocytes: role of CAMKII and repolarizing currents. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 292:H2854–H2866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grandi, E., J. L. Puglisi, S. Wagner, L. S. Maier, S. Severi, and D. M. Bers. 2007. Simulation of Ca/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II on rabbit ventricular myocyte ion currents and action potentials. Biophys. J. 93:3835–3847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tanskanen, A. J., J. L. Greenstein, A. Chen, S. X. Sun, and R. L. Winslow. 2007. Protein geometry and placement in the cardiac dyad influence macroscopic properties of calcium-induced calcium release. Biophys. J. 92:3379–3396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tanskanen, A. J., J. L. Greenstein, B. O'Rourke, and R. L. Winslow. 2005. The role of stochastic and modal gating of cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels on early after-depolarizations. Biophys. J. 88:85–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bhalla, U. S. 2004. Signaling in small subcellular volumes. I. Stochastic and diffusion effects on individual pathways. Biophys. J. 87:733–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Newman, R. H., and J. Zhang. 2008. Visualization of phosphatase activity in living cells with a FRET-based calcineurin activity sensor. Mol. Biosyst. 4:496–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kwok, S., C. Lee, S. A. Sanchez, T. L. Hazlett, E. Gratton, and Y. Hayashi. 2008. Genetically encoded probe for fluorescence lifetime imaging of CaMKII activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 369:519–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.