Abstract

Objective

To implement an introductory pharmacy practice experience (IPPE) curricular sequence in a manner that optimized preceptor availability, fostered significant learning, and addressed the new standards for experiential education.

Design

A 4-course, 300+ hour IPPE sequence was developed with 1 module in each semester of the first 2 professional years. Semesters were 18 weeks in length with IPPE taking place in the middle weeks as dedicated time blocks when no concurrent didactic courses were scheduled. Learning exercises were developed to build a progressive foundation in preparation for advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPE).

Assessment

During 2 academic years, 161 students participated in the IPPE program. Eighty-one students completed the 4-course sequence and another 80 students completed the first 2 courses. Collectively, 486 individual IPPE placements were made at over 120 community pharmacies and 60 hospital pharmacies or alternative practice sites located over a broad geographic region. Student evaluations by preceptors, evaluation of student journals by faculty, and surveys of students and preceptors demonstrated that course objectives were being achieved.

Conclusion

An innovative approach to scheduling IPPE optimized preceptor availability, exceeded the minimum number of IPPE hours required by current accreditation standards, and achieved development of desired competencies.

Keywords: introductory pharmacy practice experience, experiential education, accreditation standards

INTRODUCTION

The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) standards impacting experiential education at schools of pharmacy in the United States created a new set of challenges for pharmacy educators, with revisions effective in July 2007.1 Along with delineation of expectations in advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPEs) came new requirements for introductory pharmacy practice experiences (IPPEs), which must now be at least 5% of the curriculum or a minimum of 300 hours. Faculty members charged with experiential education responsibilities must increase the number of experiences utilizing scarce human resources (preceptors) and practice site resources.

As an emerging pharmacy program with an initial class enrolled in fall 2005, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville School of Pharmacy (SIUE) faced a challenge and an opportunity. The challenge was addressing an anticipated revision of the ACPE standards; the opportunity was a chance to develop a curriculum from the beginning that addressed and incorporated all of the anticipated accreditation revisions, particularly those related to experiential education. Our objective was to implement an IPPE program that utilized innovative curricular scheduling to optimize the availability of quality learning opportunities both near as well as outside the immediate region of SIUE, and create a progressive foundation that would prepare students for APPE.

DESIGN

SIUE has a mission to develop pharmacy practice in central and southern Illinois. Student enrollment draws heavily from this region, which is primarily comprised of smaller, rural communities and a modest number of midsized cities. Utilizing practice sites and preceptors that offered quality experiences across this region created an opportunity to address the school's mission and take advantage of underutilized experiential capacity.

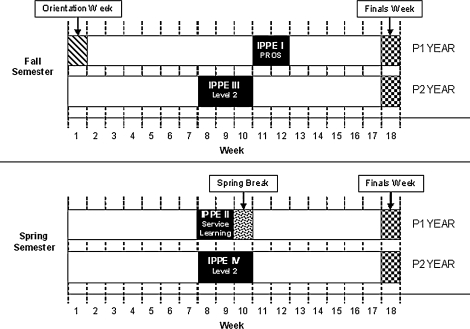

To take full advantage of preceptor and site availability throughout the region and to optimize student housing opportunities across a large geographic area, an 18-week semester was designed with dedicated time blocks created in the middle of each semester for IPPE. Fifteen weeks were dedicated to traditional courses, while the remaining 3 weeks were reserved for special programs such as IPPE. Consequently, during these dedicated IPPE time blocks, the students were not scheduled for any other coursework, allowing their full attention to be focused on the IPPE program. The time blocks allowed for 3 “traditional” IPPEs totaling 304 onsite hours and a fourth service-learning IPPE, which provided an additional 20-32 contact-hours. The IPPE time blocks were scheduled during the first 2 professional years and the sequencing of the traditional blocks occurred such that first and second year (P1 and P2, respectively) students would not be at practice sites during the same timeframe (Figure 1). During the third year, the fall and spring periods without didactic classes were used as training blocks for disease state management programs and immunization certification. These blocks could be converted to additional IPPEs in the event that more than the allotted hours during the first 2 professional years were needed when the standards revision was finalized.

Figure 1.

Block format of IPPE sequences.

Course content was designed to build on and incorporate both didactic preparation and prior experiences. The first, third, and fourth IPPEs were designed in a traditional “rotation” style where students were matched with practice sites and preceptors. The second IPPE was conceptualized as a service learning experience that encompassed a healthcare-related project. Each course was given a unique name to help students and preceptors differentiate course content and expectations.

The first IPPE was commonly presented to preceptors and students as professional role observations (PROS). This experience was conducted over a 2-week period with students spending 32 hours at a different practice site each week. Generally, 1 week was spent in a community pharmacy and 1 week in a hospital pharmacy. (Note: the first week of the fall semester in the first professional year was allocated to a student orientation program, which allowed 2 weeks for the first IPPE).2 The PROS experience might best be described as “sophisticated shadowing.” The purpose of PROS was to enhance student awareness of the role of pharmacists working in various pharmacy practice settings. Students documented required learning exercises; maintained a reflective portfolio; and attended facilitated meetings on campus before (weekly preparatory classes) and after (a debriefing session) spending time at the practice sites. Students were also required to participate in a “mini project” during their community pharmacy experience (eg, preparing a brief flyer on an upcoming immunization program) and discuss a current healthcare topic during their hospital experience. Significant self-directed learning was required. Students were also assessed on professionalism. Together the PROS experiences provided 64 hours of IPPE, with the preparatory classes and debriefing sessions not being counted towards the total IPPE hours.

The second IPPE was a service learning experience offered during the spring semester of the first year. Students participated in a healthcare-related community project where teamwork and interdisciplinary skills were emphasized. Each student spent a minimum of 20 hours working with a community agency or program. Maintaining a reflective portfolio and participation in facilitated meetings on campus was also required. Class sessions were held before the experience to prepare students and afterward to discuss and reflect on the activity. Students had the opportunity to practice the basic skills needed to provide pharmaceutical care such as critical thinking, communication, demonstrating responsibility, professionalism, researching public health information, and ethical decision-making. At the end of the IPPE, students were required to give a poster presentation describing the experience and submit written reflections. Other assessment methods were incorporated but varied depending on the service-learning project and/or the agencies involved.

The third IPPE was offered in the fall semester of the second year and the fourth IPPE was offered in the spring semester. Both were commonly presented to preceptors and students as “Level 2 IPPEs”. Each experience was 3 weeks (120 hours) in length. All 3 weeks were spent at 1 practice site. The learning exercises and assessment tools for both semesters' experiences were essentially identical but did vary somewhat based on the type of practice the students participated in (ie, community, hospital, behavioral health, long-term care). Students developed distribution and professional communication skills including patient counseling; applying patient care skills to the treatment of diverse patient populations; providing drug information; conducting medication usage reviews; addressing medication safety issues; participating as a member of an interdisciplinary health care team; developing sterile product preparation skills; managing a professional project; and giving an oral presentation to a small group. Student achievement of competencies was assessed for the content and skill areas noted above. In addition professionalism was assessed. Similar to PROS and service learning courses, students participated in preparatory classes before starting the IPPE. However, students' preparation was based on the type of practice they would be experiencing. For example, students assigned to a hospital site participated in a sterile products refresher session that included sample product preparation in a laminar flow hood. The students were also required to participate in a debriefing session after completing the fall IPPE as a quality assurance process before the program was repeated in the spring. Together the third and fourth IPPEs counted as 240 hours, which did not include time spent in preparatory classes and debriefing sessions.

Implementation of Program Design

The IPPE curricular sequence was implemented over 2 academic years, commencing with fall semester 2005. Steps in the implementation process included recruitment of preceptors during spring and summer 2005 for PROS, and in late fall 2005 through summer 2006 for Level 2 IPPEs; design of learning exercises and assessment documents; development of a process to match students with practice sites; and development of a preceptor training and assessment plan.

The recruitment of preceptors was conducted by the director of experiential education. For the initial PROS recruitment, it was anticipated that the majority of students would prefer sites in close proximity to their primary (noncampus) residence to optimize housing opportunities. Counties in the state and surrounding region were grouped into zones according to geography. The number of students from each zone was monitored and recruitment focused on creating sufficient zone-specific IPPE opportunities to meet 120% of the anticipated needs.

PROS learning exercises were originally developed in the early summer 2005 and Level 2 learning exercises were developed in the late spring 2006. The CAPE competencies served as the foundation for the course syllabi and creation of learning objectives. Specific learning exercises for both PROS and Level 2 IPPEs were subsequently developed with assistance from hospital and community pharmacy focus groups. A pharmacy practitioner in behavioral health was consulted in the design of the Level 2 behavioral health experience. The objective was to create learning plans that fostered quality learning experiences for students, were contemporary in approach, complemented and enhanced didactic preparation, were progressive from PROS to Level 2, created a foundation for APPE, were appropriate for the practice setting, and were realistic for preceptors to implement.

PROS exercises were designed as a rubric and students were required to make journal entries for preceptor and faculty review as a means of assessing performance. Level 2 IPPEs were also designed as rubrics with specific criteria for “needs improvement,” “satisfactory,” or “outstanding.” Individual Level 2 rubrics were created for community pharmacy, hospital pharmacy, and behavioral health. Rubrics to assess projects, presentations, and professionalism were developed by SIUE faculty members and were the same throughout the IPPE sequence.

With over 160 student IPPE placements required in the first year of program implementation and over 320 IPPE placements required in the second year of the program, a decision was made to acquire site placement and IPPE management software to facilitate the process. Additionally, implementing experiential software was thought to be less labor intensive if the database was grown along with the development of the experiential program. Education Management Systems (EMS) software was licensed from ROI Solutions, Glendale, Arizona and implemented.

Preceptor training sessions were offered in fall 2005 and fall 2006 and included on campus programs, a program at a local pharmacy association meeting, and teleconferences. The 2005 program was designed to introduce preceptors to a new school of pharmacy, with particular emphasis on the overall curricular design, curricular correlation to experiential learning, and the “block scheduling” method for IPPEs. Learning exercises for the PROS program were also detailed, along with preceptor expectations and assessment methodology. Various forms were reviewed and the use of the EMS system was discussed. In 2006, preceptor training built on the 2005 program, introducing the Level 2 IPPE learning exercises and explaining how they built on the PROS experience. The sessions afforded an opportunity to introduce the forthcoming changes in ACPE standards and were also used to articulate why experiential education is a significant learning experience for students.

A multi-faceted assessment plan was developed to review the IPPE program, determine achievement of goals, and identify opportunities for improvement. Information on both operational and academic issues was gathered from key constituents including students, preceptors, and collaborating service agencies.

Following IPPE offerings, course surveys and facilitated discussions were conducted to gauge students' overall impressions of the IPPE experience and the value of preparatory meetings. An open comment section was included on the survey instrument for students to voice any additional suggestions or concerns. The PROS course assessment for 2006 was conducted using an electronic 7-question survey instrument with anonymous submission. Participation was voluntary. A similar survey process utilizing a 9-question survey was used for the Level 2 course assessment in fall 2006.

Faculty members were interested in determining the students' ability to correlate didactic preparation with practice experiences. To address this issue, each student was asked to answer the following reflective question and record the answer in a journal at the end of the first and second weeks of each Level 2 IPPE: “Consider your pharmacy classroom instruction. Describe a professional experience activity you participated in during the past week and how your classroom instruction prepared you for the activity.” Student responses were reviewed by the authors and each reference to a particular class was recorded.

Feedback from pharmacist preceptors and external agencies collaborating on IPPEs was a key element of the overall assessment plan. Preceptor feedback focused on 3 areas: (1) the preparation of the students for the experience; (2) the block scheduling methodology; (3) the design of the learning exercises and student journaling expectations. Preceptor feedback was collected from unsolicited comments to experiential education faculty members, preceptor comments during faculty site visits, preceptor focus groups and the experiential education advisory committee. Additionally, a preceptor survey was conducted in spring 2007. The SIUE School of Pharmacy Experiential office sent an introductory letter to all active IPPE preceptors and invited them to complete a Web-based survey. For those preceptors who did not have Internet access, a survey was sent via mail to their work address. Participants were asked to complete the survey within 2 weeks.

Feedback from service learning collaborating agencies was collected during a post project review meeting with the collaborating agencies in 2006 and through student assessments performed by project collaborators concurrently with the 2007 project.

ASSESSMENT

At the conclusion of the preceptor recruitment implementation phase in fall 2006, over 50 hospitals and alternate sites were providing over 200 placement opportunities for students (161 hospital/alternate site placements were needed for PROS and Level 2). The number of central and southern Illinois student placement opportunities was approximately 66% of this total. Over 100 community pharmacies provided in excess of 360 student placement opportunities (161 community placements were needed for PROS and Level 2). Approximately 95% of these placement opportunities were located in central and southern Illinois. For the initial 2 years of the IPPE program, 486 IPPE placements were made at over 120 community pharmacies and 60 hospital pharmacies or alternative practice sites, which were primarily located in Illinois.

Key findings for PROS based on facilitated discussions of small groups of students in 2005 were that learning exercises needed to be better defined for students and preceptors, and that journaling requirements were too extensive. Similarly, preceptors also indicated that journaling requirements for students were too time consuming and needed streamlining.

Forty-two respondents from a class of 80 students (52.5% response rate) completed the 7-question PROS survey instrument and comment section in 2006. Key findings were: 85.7% of respondents felt that there was adequate class time spent reviewing learning exercises; 73.8% of respondents felt adequately prepared, with 21.4% providing a neutral response and 4.8% not feeling adequately prepared; 80.9% of respondents felt it would be helpful to have hospital and community pharmacy preceptors make brief presentations to the class regarding their expectations of students on IPPEs. No themes were noted in the student comments. Forty-four students responded from a class of 81 (54.3% response rate) to the 9-question Level 2 survey instrument plus comment section. Eighty-eight percent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed they were adequately prepared for the learning experiences, and no students disagreed. Of the 19 students assigned to hospital pharmacies who participated in a sterile products refresher laboratory, 13 (68%) felt it was beneficial, while 3 students (16%) gave neutral responses. There were no themes noted in the student comments.

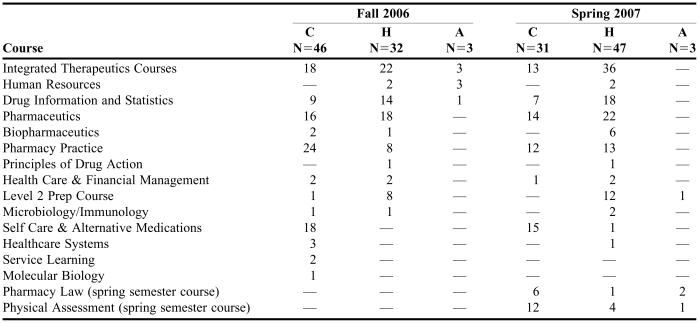

Preceptors' assessment of students' achievements subsequent to the learning experiences indicated that curricular competencies were being achieved. Correlations of didactic experiences with practice activities during Level 2 IPPEs were recorded in student journals. Tabulations indicate that students were able to both identify and apply their didactic preparation to practice activities (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of Times Courses Were Correlated to Didactic Coursework During Practice Experiencesa

Abbreviations: C=community practice; H=hospital practice; A=alternate site, eg, long-term care or behavioral health

Level 2 Academic Year 2006-2007

In April 2007,152 survey instruments were distributed to preceptors; 30 were sent via US mail and 122 via e-mail. Sixty-three participants completed the survey for a response rate of 41.4%. Experiential education faculty members tabulated responses, including correlation of suggestions offered in an open comment section. The comment section (32 responses) reflected general satisfaction with the structure of the IPPE program. However, several respondents recommended shortening the program or lowering student expectations. Seventy-three percent of respondents requested that sample calculation problems based on the students' level of didactic preparation (P1 or P2) be added. Thirty-five percent of preceptors indicated they overlooked, were unaware of, or did not have time to review students' journals. Respondents also felt that preceptor training should be offered as a telephone conference (72%) or a series of 7-10 minute “podcasts” (73%) rather than “live” programs (63%). Preceptors uniformly described the students as well prepared for the learning experience. The block scheduling was well received with only 1 preceptor indicating a preference for longitudinal placement over a semester. Preceptors commented that the learning exercises reflected challenging but realistic expectations for the students.

Post-IPPE II (service learning) discussions with collaborators on the 2006 program (educating seniors on Medicare Part D) resulted in no substantive recommendations for change. The class received an award from the Association of State Pharmacy Association Executives for their activities and the School of Pharmacy was presented with an SIUE Student Leadership and Development Award for work in the community. The 2007 service learning program provided 342 poison education programs to over 8,000 preschool and elementary school children in the SIUE region. Teachers in the classes visited assessed the pharmacy students' presentations by completing a 12-item questionnaire that addressed course learning objectives. There were 319 respondents with 98% agreeing or strongly agreeing that all learning objectives had been met. All but 1 respondent indicated they would invite the presenters back.

DISCUSSION

In developing the curriculum for an emerging program, the curricular design team members for SIUE were aware of the probable changes in ACPE standards and took particular note of potential increases in the amount of IPPE that would be required. As a new program starting with a “clean slate,” there was a clear opportunity to proactively address incorporation of anticipated IPPE requirements utilizing an innovative approach. Based on information available at the time of curricular design, the team projected the maximum needs for IPPE hours. If the requirements turned out to be less stringent, it was felt the added training would still benefit student preparation for APPE.

The objectives for the first 2 years of the IPPE program were met or exceeded. Our 2007 and 2008 updates to the ACPE, which included a full description of this program, were well received. Preceptor recruitment was and continues to be facilitated by our ability to disperse placements over a wide geographic area. Initial concerns of over-saturating preceptors and sites with students from our program as well as others in the region were prevented by utilizing the block scheduling format. This approach has also helped recruit new preceptors in rural areas who previously had not been involved in experiential education. Without the dedicated time blocks, preceptor recruitment would have been much more problematic secondary to student travel considerations and concomitant didactic coursework.

Preceptor satisfaction with the program has been extremely positive, resulting in their continued willingness to participate as pharmacist educators. Preceptors were receptive to the mid-semester IPPE blocked experiences and the learning exercises. Recommended changes to the format of the student journal and rubric design used in the first IPPE I during fall 2005 were implemented and preceptors have been extremely receptive to the modifications.

The results of the 2007 preceptor survey identified several areas for further program improvement: student evaluation, preceptor training, and student journals. Numerous preceptors had prior experience with APPE students, pharmacy interns, or student workers, but many were unfamiliar with IPPE students before our program. Consequently there was some uncertainty among preceptors as to what represented reasonable expectations for students so early in their pharmacy career. Despite annual preceptor training offerings and rubrics for each objective, input from preceptors indicated that they needed more guidance to effectively evaluate certain aspects of student performance. Specifically, assistance with pharmaceutical calculation exercises led preceptors to seek sample problems that were appropriate to the IPPE student's level of didactic preparation. In response to this concern, sample calculations packets tailored for the various levels of IPPEs in the community and hospital settings were prepared and distributed to preceptors with the fall 2007 course offerings. Problem sets had increasing levels of difficulty from the P1 to P2 years and were based on coursework completed prior to the IPPE. In response to the preceptors' requests for other training modes than live presentations, a series of brief (8-minute) preceptor training podcasts were developed and posted on the experiential education web site and the number of teleconference training sessions was increased. Finally, in an effort to increase awareness of the importance of the student journals, preceptor training has been modified to include a component on reviewing student journals.

With regard to the preceptors' feedback concerning the amount of time required to review students' journals, follow-up after future course offerings will be needed to determine whether this problem is isolated to particular preceptors and practice settings or whether a more “preceptor friendly” method of journal review is required. Simply stressing quality over quantity to students regarding their journal entries improved the situation somewhat from the first to the second year of the program. Preceptor comments suggesting that the IPPE program be shortened or expectations lowered have not resulted in any programmatic changes. ACPE standards prevent shortening the program and academic requirements prevent lowering expectations for students. These comments likely reflect some misunderstanding on the part of preceptors and were addressed in a follow up document sent to all preceptors invited to participate in the survey.

Service learning has given the students and the school an opportunity to reach out to the community. The success of the first 2 programs has established credibility, and resulted in more opportunities than we can address. Going forward, this will allow us to be selective and create optimal learning experiences for students that also have a major impact on the community.

The correlation of didactic coursework to practice experiences by students has provided a tool for faculty members to use in assessing the applicability of lecture content to contemporary practice situations. Students' responses indicate that didactic courses have prepared them for a variety of day-to-day situations encountered by pharmacy practitioners. Based on the data collection from Level 2 activities in fall 2006 and spring 2007, this would appear to be information worth collecting on a routine basis and sharing with faculty members.

The most important element of any learning experience is student achievement of the learning objectives. Based on preceptor assessment of students, student surveys, comprehensive review of student journals by faculty members, and the students' ability to correlate didactic preparation to practice experience, there is sufficient evidence to conclude that this key element has been achieved. Continued follow up through the APPE experiences is planned and will be important to verify that a proper experiential foundation was laid during IPPEs. In addition, as we go forward, the IPPE learning objectives must be kept dynamic and evolve to assure that relevant and contemporary learning experiences are occurring.

CONCLUSION

A contemporary curricular sequence of introductory pharmacy practice experiences has met the stated objectives of optimizing preceptor availability, fostering significant learning experiences, and addressing the new (2007) ACPE standards for experiential education.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge Theresa McCullough, PharmD, for her correlation of the 2007 preceptor survey data, and Erin Timpe, PharmD, for her recommendations on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree. Adopted January 15, 2006. Available at http://www.acpe-accredit.org/. Accessed July 3, 2007.

- 2.Poirier TI, Santanello CR, Gupchup GV. A student orientation program to build a community of learners. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71 doi: 10.5688/aj710113. Article 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]