Abstract

Objectives

To determine recognition given for outstanding teaching, service, and scholarship at US colleges and schools of pharmacy, the types of awards given, and the process used to select the recipients.

Methods

A self-administered questionnaire was made available online in 2006 to deans at 89 colleges and schools of pharmacy.

Results

Sixty-four usable responses (72%) were obtained. An award to acknowledge teaching excellence was most commonly reported (92%), followed by an award for adjunct/volunteer faculty/preceptors (79%). The majority of the institutions (31 out of 58) reported offering 1 teaching award annually. The 2 most common methods for selecting the recipient of the teaching award were by student vote and by college/school committee vote following nominations. Twenty-four of the 63 respondents indicated that their institution provided an award for research/scholarship and 18 offered an award for outstanding service.

Conclusions

Teaching excellence was recognized and rewarded at most US colleges and schools of pharmacy; however, research/scholarship and service were formally recognized less frequently.

Keywords: faculty awards, faculty retention, preceptor awards, awards

INTRODUCTION

A faculty member's responsibilities consist of 3 major domains: teaching, service, and scholarship. Little data exist in the pharmacy education literature regarding the recognition provided to full-time and/or volunteer/adjunct faculty members for outstanding efforts in these areas at US colleges and schools of pharmacy. Smith reported the results of a 1991 survey of how colleges/schools of pharmacy select and reward teaching excellence (ie, Teacher of the Year awards).1 Of the 47 respondents to the survey (75 colleges/schools of pharmacy existed at the time), 40 indicated that their college/school sponsored an award for teaching. Although methods varied, 20 out of 40 respondents reported that student voting largely determined the award recipient. In 2003, Draugalis reported that 89% (70 out of 79 respondents) of colleges/schools of pharmacy provided at least 1 award per year for teaching.2 Methods of selecting the award recipients varied, but student voting was reported to be the most common method. In addition, 16 institutions indicated that an award was provided to recognize preceptors.

Recruitment and retention of faculty members has been an issue discussed in academic pharmacy for many years.3-8 In the 1990s, when many programs were moving to the doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) degree as the first-professional degree there was an increased demand for pharmacy practice faculty members. Lee and colleagues recommended, among other items, that a faculty member's intrinsic job satisfaction could be enhanced if there was “a formal reward and recognition system for meritorious performances on-the-job.”4 In 2006-2007 (the latest data available), the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) reported 582 vacant and 13 lost faculty positions, which was up from 408 vacant and 21 lost positions in 2005-2006.9 Of the 595 vacant and/or lost positions, the greatest percentage were in the clinical sciences (51.3%), followed by the pharmaceutical sciences (29.0%), social and administrative sciences (7.9%), administrative (7.0%), and research/noninstructional (4.5%). The most common reasons reported for the vacant positions were relocation to a different college or school of pharmacy, retirement, and accepting a position in the health care private sector.9 The need to recruit and retain faculty members is a crisis affecting the academy; thus, all strategies that might increase faculty recruitment and retention need to be examined.

Given the limited data on the forms of recognition provided for outstanding teaching and the lack of data on awards for service and scholarship, the aim of the current study was to characterize the types of awards available to faculty members at colleges and schools of pharmacy in the United States. A secondary objective was to identify the processes used to grant the awards.

METHODS

A questionnaire was designed to be self-administered and available online through a commercial vendor. Persons at 4 different colleges and schools of pharmacy reviewed a draft of the survey for completeness, ease of completion, clarity, and overall suitability. These individuals were selected because they have expertise in survey design and/or knowledge of the subject area. Following modification, the survey instrument and cover letter were submitted to the institutional review boards at Long Island University and Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences. Both institutions granted exempt status to the research project.

In mid-February 2006, an e-mail message was sent to the deans of 89 colleges and schools of pharmacy in the United States and Puerto Rico with enrolled students to complete the online survey created in SurveyMonkey. The e-mail noted that if the dean was not the ideal person to respond, he/she could forward the e-mail message to a more appropriate person or notify the authors that the instrument should be sent to a different individual. Duplicate e-mail messages were sent to nonrespondents approximately 4 weeks later, and telephone calls were made or e-mail messages sent to persons who did not respond to the second request. On occasion, a final e-mail message was sent to an associate dean or other administrator rather than the dean.

Survey responses were collected online via SurveyMonkey.com (SurveyMonkey.com, Portland, OR). This software was also used to generate descriptive statistics consisting of frequencies, percentages, or means (± SD) associated with each item on the questionnaire. Further analyses were conducted to determine whether significant differences existed between and among these values within each question. Fisher's exact tests were used for percentages, while analysis of variance and Bonferroni post-hoc testing were used for means. All analyses were performed using NCSS 2000. Differences assessed were considered statistically significant if the observed level of significance was p<0.05.

RESULTS

Sixty-six people responded to the survey; however, 2 did not wish to complete the questionnaire, resulting in 64 usable responses (72% response rate). Fifty-eight (94%) of 62 respondents noted that their college or school was part of a university, while 4 (7%) indicated that their institution was not (P<0.05). More persons from public rather than private institutions participated in the survey (P<0.05). Specifically, 41 (65%) of the 63 respondents reported that their college or school was a public institution, 22 (35%) reported that their college or school was private. The percentage of respondents from public and private institutions was similar to the ratio of public (62%) to private (37%) colleges of pharmacy nationwide at the time the survey was conducted.

Fifty-six (89%) of the 63 institutions responding had been graduating students for more than 10 years (P<0.05 versus any other category), 3 (5%) for 5 to 10 years, another 3 (5%) for fewer than 5 years, and 1 college/school (2%) enrolled students but has not had graduates from its program.

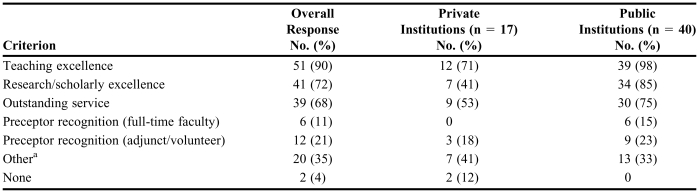

Table 1 depicts the type of awards available to pharmacy faculty members by respondents' universities. The most common award provided was for teaching excellence (P<0.05). Most respondents noted that a single award was available in each category (P<0.05 versus any other time sequence) and the award was provided on an annual basis (P<0.05).

Table 1.

Faculty Awards Provided by US Universities for Which Pharmacy Faculty Members Are Eligible, N = 57

aExamples include the following: outstanding advisor, instructional technology, mentor of the year, longevity awards

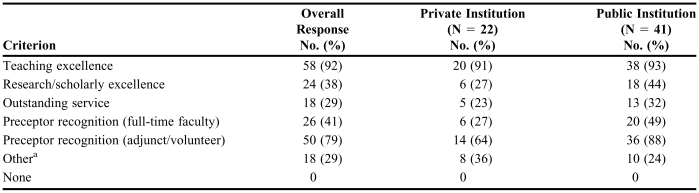

Table 2 delineates the types of awards provided directly by colleges and schools of pharmacy to faculty members and volunteer/adjunct faculty members. An award to acknowledge teaching excellence was most commonly reported, followed by an award to recognize volunteer/adjunct faculty members (P=NS). Awards for research, service, and precepting for full-time faculty were less frequently reported (P<0.05 as compared to teaching award). Similar to awards provided by the universities, most colleges and schools of pharmacy offered only 1 award in a given category, although there were several exceptions. For example, although 31 out of 58 (53%) respondents reported that their institutions provided only 1 award for teaching excellence, 12 others provided 2 awards, 3 provided 3 awards, 8 provided 4 awards, 1 provided 6 awards, and 3 provided more than 10 awards. As another example, although 35 of 52 (67%) respondents provided 1 award to recognize a volunteer/adjunct faculty preceptor, 9 colleges/schools reported that they had 2 awards, 3 had 3 awards, 1 had 4 awards, 1 had 5 awards, and 3 had more than 10 awards. Virtually all colleges/schools provided the award on an annual basis only (P<0.05).

Table 2.

Faculty Awards Provided by US Colleges and Schools of Pharmacy (N = 63)

aExamples include the following: outstanding advisor, instructional technology, mentor of the year, longevity awards

A total of 49 responses were received concerning the selection process used to determine the teaching award recipient. Twenty of the 49 respondents indicated that a student vote was the only method used to select the recipient, 9 out of 49 respondents noted that a college/school committee vote following nominations was the only method used, and 3 of 49 indicated that the selection was solely an administrative decision. Seventeen of the respondents indicated that multiple methods were used to select the award recipient; 9 of these 17 identified student voting as one of the methods. Less commonly used methods included a review of supporting materials by a faculty committee and reviews of teaching portfolios.

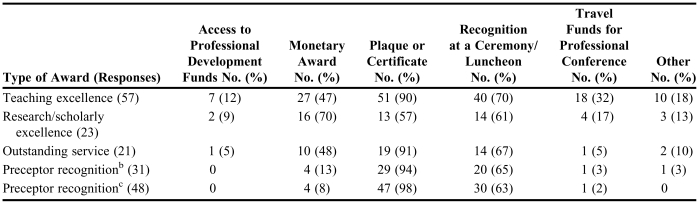

Based on 57 responses, faculty members are permitted to receive the award more than 1 time (55 [97%]; P<0.05) and in 57% of the cases, 1 year must pass before a faculty member becomes eligible to receive the award again. The most common criterion for award eligibility is being a full-time faculty member (39 out of 57 [68%] respondents; P<0.05 versus any other category). Award recipients may receive a plaque, recognition at a ceremony, a monetary gift, travel funds, etc. The monetary gift for this or any other award was highly variable, and ranged from $500 to $4000 (only one respondent noted $4000, no other response exceeded $2000), with the most common amount being $1000. A summary of the type of awards received is in Table 3. Finally, 51 (90%) of 57 respondents indicated that the award recipient was also the person chosen to attend the Teachers' of the Year Award Luncheon held at the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy's annual meeting (P<0.05).

Table 3.

Items Received by Faculty Award Recipients at US Colleges and Schools of Pharmacya

Multiple responses exist

bOnly full-time faculty members eligible

cOnly adjunct and volunteer faculty members eligible

There were 20 responses concerning the methods (or stepwise procedures) used to select the recipient of the research/scholarship award. Twelve (60%) of the 20 respondents indicated that only 1 method is used to select the award recipient (6, administrative decision; 5, committee vote following nominations; and 1, vote of the faculty members). Four (20%) respondents noted that 2 methods were used to select the award winner, while 4 respondents (20%) indicated that 3 methods were used. Twenty-one (91%) of 23 respondents indicated that the award could be received more than once (P<0.05 may versus may not be received more than once), while 14 (70%) of 20 respondents noted that only 1 year must pass before an award recipient was eligible to receive the award again. Similar to the teaching award, although multiple responses existed, the most common criterion for award eligibility was being a full-time faculty member (16 out of 19 [84%] respondents), followed by a requirement that the research/scholarship was conducted at the current institution (11 out of 19 [58%] respondents, P=NS). A summary of the awards is given in Table 3.

There were 20 responses dealing with the method used to select the winner of the service award. Fourteen of these respondents (70%) reported that one method is used to select the award recipient (7, administrative decision and 7, by committee vote following nominations), while 3 indicated that 2 methods are used, and another 3 respondents indicated that 3 methods or steps are used. The majority of respondents (19 out of 22, 86%) reported that the award recipient could win the service award more than once, while 3 respondents (14%) indicated only once (P < 0.05). Similar to the other awards described so far, of the 14 responses, 6 (43%) indicated that only 1 year need pass before the recipient was eligible for the award again. The most common criterion for determining eligibility for the award was being a full-time faculty member (15 out of 16 responses; 94%, P < 0.05).

Twenty-seven responses were received concerning the methods used to select the preceptor award from among full-time faculty members. Sixteen (60%) of the 27 reported that 1 method was used (9, student vote; 3, administrative decision; 3, college/school committee vote following nominations; and 1, course evaluation surveys). In addition, 6 respondents noted that 2 methods were used, 4 respondents indicated that 3 methods were used, and 1 respondent indicated that 4 methods were used. Thirty responses were received concerning the criteria used to select the preceptor award from among full-time faculty members. The most common method cited was a student vote (15 respondents; 50%) followed by an administrative decision (10; 33%). Similar to previous questions, most respondents indicated that a faculty member could win the award more than once and only 1 year must pass before the preceptor was eligible for the award again.

Forty-three responses were received concerning the methods used to select the preceptor award from among the volunteer/adjunct faculty members. Twenty-four (56%) of the 43 reported that 1 method was used (11 by student vote; 9 college/school committee vote following nominations; 3 an administrative decision; and 1 course evaluation surveys). In addition, 9 respondents indicated that 2 methods were used. Six respondents indicated that 3 methods were used, and 4 respondents indicated that 4 methods were used. A total of 49 responses were received concerning the criteria used to select a volunteer or adjunct faculty member to receive a preceptor award. In most instances, a preceptor could win the award more than once (42 out of 46 responses; 91%) and only 1 year need pass before the winner would once again be eligible for the award (26 out of 33 responses; 79%). Similar to the awards given to full-time faculty members, a plaque or certificate was the most common item given to award recipients (Table 3).

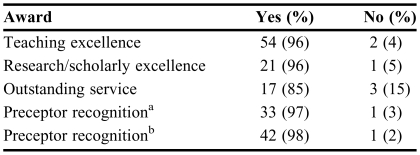

Respondents were asked whether award recipients for the previous 2 years were still employed by their college or school of pharmacy. The response rates are depicted in Table 4.

Table 4.

Award Recipients for the Previous Two Years Still Employed at/Affiliated With the College/School of Pharmacy

aOnly full-time faculty members eligible

bOnly adjunct and volunteer faculty members eligible

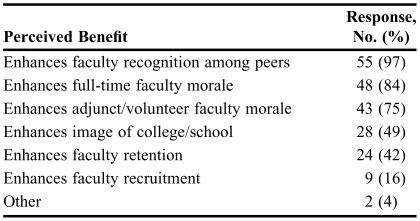

Respondents were queried about the perceived benefits of faculty awards. As shown in Table 5, multiple responses were received from the 57 respondents to this question. The most common belief was that awards enhanced faculty members' recognition among their peers followed by enhancing faculty and volunteer/adjunct faculty morale.

Table 5.

Perceived Benefits of Faculty Awards (N = 57)a

Multiple responses exist

DISCUSSION

This study expands the data from 2 previous reports1,2 on awards provided for teaching at colleges and schools of pharmacy to include awards for research/scholarship and service along with awards recognizing preceptors. The results of the current study indicate that the practice of recognizing teaching excellence through a college/school award continues to be common. Also, the percentage of colleges/schools providing an award for teaching excellence appears to be increasing, from 85% in 1994,1 to 89% in 2003,2 to the 92% reported in this study. Although not specifically addressed in the study by Draugalis, some institutions reported that awards were provided to preceptors.2 The current study addressed this issue specifically and concluded that colleges and schools of pharmacy provide awards for preceptors/volunteer faculty members with a high frequency (79%). In comparison, less than 50% of colleges and schools of pharmacy provide awards to recognize research/scholarship and service. Providing awards (which might include only public recognition) for outstanding or noteworthy research/scholarship and service is something that all institutions should consider.

Similar to the data reported by Draugalis,2 a variety of methods are used to select the recipients of teaching awards. Student voting is still the most common method for selecting awards for teaching excellence. The current survey did not assess the criteria used by students at colleges and schools of pharmacy to select the award recipient.

The issue of recognizing and rewarding teaching excellence has been discussed within academic pharmacy for some time.1,2,10 In a survey of junior faculty members at colleges and schools of pharmacy that assessed satisfaction with academic roles,11 the respondents indicated that they were dissatisfied with institutional teaching rewards. In another study conducted at a single institution, faculty members indicated that they placed a greater value on winning an award for research than teaching.12

Establishment of criteria for best practices with regard to selection of teaching award recipients would help to standardize these awards across colleges and schools of pharmacy and might lead to a higher level of satisfaction among junior faculty members. Draugalis reported a series of best practices in place for teaching awards at colleges and schools of pharmacy, including detailed information on application forms (eg, award criteria, eligibility, selection process), establishment of a selection committee with diverse membership, and awards for teaching in a variety of settings.2 Combining the suggestions of Kinnard,10 Chickering and Gamson,13 and Bain,14 criteria for selecting teaching award recipients could include the following: possessing knowledge of the discipline, demonstrating enthusiasm toward teaching, promoting active learning, providing instruction that matches the learning objectives, continually assessing students' achievement of those objectives, providing prompt feedback to students, establishing and communicating high expectations, and displaying empathy and respect for students.

Also, each institution should ensure that the criteria used to select award recipients are aligned with its mission and goals, and that the criteria are sufficiently flexible to account for different educational settings (eg, didactic, lecture, small-group learning, laboratory, and practice). Therefore, it appears that one set of criteria for all institutions is not feasible. Criteria should be clearly communicated and available for public review. As postulated by Draugalis,2 it is important that differences in the criteria and methods used to select teaching award recipients be recognized by external audiences when serving as reviewers for promotion/tenure dossiers and/or when participating in hiring decisions.

Institutional teaching award programs should be evaluated for effectiveness. Menges suggested 3 “tests” that award programs should pass15: (1) selection validity test (award recipients should be the best teachers); (2) faculty motivation test (the award program results in faculty members improving the quality of their teaching); and (3) public perception test (the award program should result in external audiences believing the institution values effective teaching). Finally, the development of programs such as teaching academies might be a more effective means of fostering large-scale improvements in the quality of teaching at an institution.16

Not surprisingly, the process(es) utilized to determine the award recipients for research/scholarship and service were most commonly either an administrative decision or a committee decision. The most common process to select both full-time faculty and adjunct/volunteer faculty awards for preceptors was a student vote; however, other methods including administrative decisions and committee votes were noted.

Plaques or certificates were the most common items received by recipients of all awards, with the exception of awards for research/scholarship for which a monetary award was most common. In the surveys by Smith1 and Draugalis,2 the range of monetary awards accompanying a “teacher of the year” award were similar, with $1000 being the most common amount. In the current study, findings were similar. Perhaps it is time that institutions reviewed the monetary gifts and increased the dollar amounts.

Most recipients remained employed by their respective institutions 2 years following receipt of an award, suggesting that awards might enhance faculty retention. Future research should evaluate this issue, looking at faculty member retention 5 or 10 years following receipt of an award. Awards also appear to enhance faculty morale and recognition among peers.

CONCLUSION

Although the methods vary, teaching excellence is commonly recognized and rewarded at US colleges and schools of pharmacy; however, research/scholarship and service are formally recognized with an award less frequently. Awards for teaching, scholarship, and service may positively impact faculty recruitment, retention, and satisfaction and thus should be considered by all colleges and schools of pharmacy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge Gary Tataronis, Associate Professor School of Arts and Sciences, Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences for conducting the statistical analysis for the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith MC. Selecting and rewarding best teachers in US schools of pharmacy. J Pharm Teach. 1994;4:31–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Draugalis JR. Teaching award and recognition programs in U.S. schools and colleges of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;66:112–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobs EW, Spratto GR, Roche VF, Cormier FJ, Maddox RW, Oderda GM. Am J Pharm Educ. 1993;57(Suppl):43S–54S. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee M, Abate MA, Fjortoft N, Linn A, Maddux MS. Report of the task force on the recruitment and retention of pharmacy practice faculty. Am J Pharm Educ. 1995;59(Suppl):28S–33S. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Penna RP. Academic pharmacy's own workforce crisis. Am J Pharm Educ. 1999;63:453–4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter O, Nathisuwan S, Stoddard GJ, Munger MA. Faculty turnover within academic pharmacy departments. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37:197–201. doi: 10.1177/106002800303700206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leslie SW. Pharmacy faculty workforce: increasing the numbers and holding to high standards of excellence. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(05) Article 93. [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Foundation for Pharmaceutical Education. Acute Shortage of Faculty at U.S. Pharmacy Schools Threatens Efforts to Solve Nation's Pharmacist Shortage. Available at: http://www.afpenet.org/news_acute_shortage.htm. Accessed August 25, 2007.

- 9.Vacant Budgeted and Lost Faculty Positions – Academic Year 2006-07, AACP Institutional Research Brief, American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, Available at: http://www.aacp.org/Docs/MainNavigation/InstitutionalData/8695_IRBNo8-Facultyvacancies.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2008.

- 10.Kinnard WJ. Teaching and its encouragement (some post-decanal ramblings) J Pharm Teach. 1994;4:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Latif DA, Grillo JA. Satisfaction of junior faculty with academic role functions. Am J Pharm Educ. 2001;65:137–43. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desselle SP, Mattei TJ, Vanderveen RP. Identifying and weighting teaching and scholarship activities among faculty members. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(4) Article 90. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chickering AW, Gamson ZF. Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin. 1987;39:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bain K. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 2004. What the best college teachers do; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menges RJ. Awards to individuals. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. 1996;65:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chism NVN, Fraser JM, Arnold RL. Teaching academies: Honoring and promoting teaching through a community expertise. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. 1996;65:25–32. [Google Scholar]