Abstract

Objectives

To describe the design of a required service-learning course offered to first- year (P1) pharmacy students, and to assess student learning and the relevance of this learning in the pharmacy curriculum.

Design

A 14-week service-learning course was designed and community organizations were recruited to participate. All first-year students enrolled in the School completed the course. A post-course survey was administered to the students, inquiring about what they had learned from the course; supervisors at the students' service sites also completed a short survey.

Assessment

The course and the student survey instrument were completed by 195 students, and of these 190 gave permission for the information they provided to be used in the study. Notable learning outcomes were identified, especially in the areas of communication and the social and behavioral aspects of pharmacy.

Conclusion

The survey administered at the conclusion of the course described in this article demonstrated that students in the course had achieved the desired learning outcomes. This shows that service-learning is a pedagogy that educators can employ to effect relevant learning in the pharmacy curriculum.

Keywords: service-learning, educational outcomes, community service

INTRODUCTION

The place of service-learning in healthcare education generally, and in pharmacy education specifically, has been the subject of much discussion among educators.1-6 In 2006, the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) issued Accreditation Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree7 (Standards 2007), and in this document specified what constitutes appropriate and relevant service-learning activities. The promulgation of the Standards offers an opportunity to assess how service-learning experiences are being implemented in pharmacy education.

The hypothesis of this study was that a service-learning course for first-year (P1) pharmacy students could impart knowledge and insights that the students could apply in future pharmacy courses and ultimately in their careers. The subject of the study was a course that had been offered annually for 8 years to P1 students at the Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences (MCPHS), School of Pharmacy-Worcester/Manchester (SOP-W/M). This manuscript describes the design of the course, and the results of the study.

This paper builds on and adds to earlier work. An earlier study, using pre- and post-course surveys, examined the perceptions and attitudes of students in service-learning courses, and explored specific learning outcomes for service-learning and the factors that may affect those outcomes.8 While pointing to possible learning outcomes, that study was limited by its subjectivity: students simply rated their own knowledge about certain topics. The present study, using only post-course surveys, instead asked students to indicate more explicitly what they have learned.

This paper also builds on the work of others who have studied the educational outcomes of service-learning, especially the work of Eyler et al.9,10 There is ample evidence in the literature of what students learn from service-learning, and the present study focuses on that learning with reference to its place in pharmacy education.

DESIGN

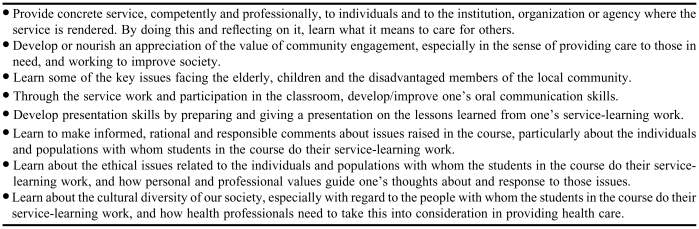

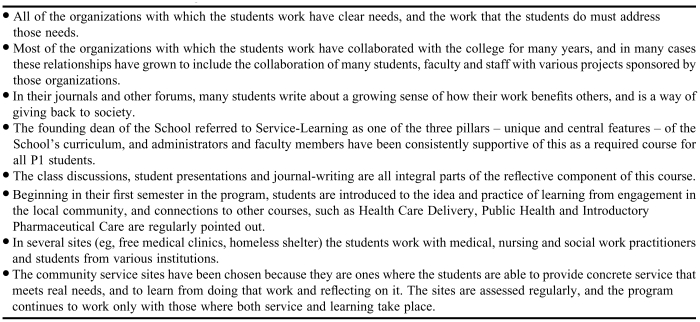

The MCPHS SOP-Worcester/Manchester offers a transfer-in professional program. Students complete their prepharmacy course work at other institutions before being accepted and beginning their first year at SOP-W/M. The School aims to educate community-oriented pharmacists. Toward this end, community-based educational experiences are integrated throughout the School's curriculum. In fall 2006, the first such experience, in the first semester of the first year of the curriculum was part of a 1-credit, required course entitled Service-Learning. The same course, following a common syllabus and schedule, was taught on the Worcester, Massachusetts, and Manchester, New Hampshire, campuses of the School by 2 instructors who worked closely to coordinate their efforts. The service and learning objectives of the course are shown in Table 1. These were listed in the course syllabus and explained to the students at the beginning of the course.

Table 1.

Course Service and Learning Objectives

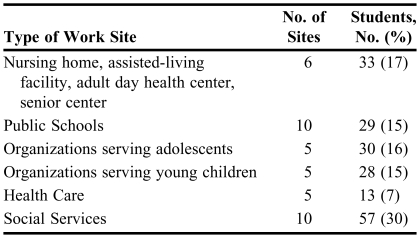

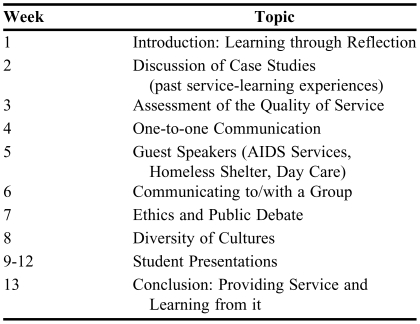

For their community service work, students were assigned to sites matched as closely as possible with preferences they had expressed. The types of sites/organizations and number of students working at each are listed in Table 2. At most of the sites, even those providing health care, the students provided general, and not specifically health-care, assistance. Students were required to spend an average of at least 2 hours per week providing service at their service-learning site, for a total of approximately 20 hours of service during the semester. Students participated in a 1-hour class/seminar each week (topics are listed in Table 3). Readings were assigned for some of these classes, and most of the classes involved significant student participation in discussions. For the fifth class of the semester, representatives of several of the organizations where students were doing their service work spoke to the entire class about their organizations. For classes during the 9th through 12th weeks of the semester, students gave presentations about their service work and what they were learning from it. Students were required to purchase and make weekly entries in a journal. The journal posed specific reflection questions for each week and included guidelines for reflecting on and learning from service experiences.

Table 2.

Types of Work Sites/Organizations and Number of Students at Each Typea

Based on answers from 190 respondents who gave permission to use this information

Table 3.

Major Course Topics

This course was designed to embody the principles of learner-centered teaching and andragogy.11,12 Much of the learning took place through the students' reflection on their service in the community, and through discussion in the classroom (learner-centered teaching). Efforts were made to motivate the students to learn by explaining the connection between their community service and pharmaceutical care (andragogy).

This service-learning course took into consideration that the students had little or no previous training in pharmacy. Its goal was to introduce the students to the concept and practice of providing service and care in a variety of settings where knowledge of the pharmaceutical sciences was not required.

During the 14-week course, students engaged in a variety of classroom activities, such as: discussing case studies and how to reflect on and learn from them, observing and practicing communication exercises, discussing what constitutes effective service, and engaging in debate about public policy issues. A brief description of the activities for the class on the diversity of cultures (week 8) is given as an example: Two weeks before the class, students were asked to submit the names of cultural or ethnic groups of which they were members or which they had encountered in their community service work. The instructor then reviewed these, and 1 week before the class, assigned a cultural or ethnic group to each student, based on the information provided. Each student was asked to come to class the following week prepared to describe what healthcare providers should know about her/his assigned group. This was done in such a way that most major cultural and ethnic groups would be represented, and so that each student would talk about her/his experience either as a member of that group or as someone who was working with members of that group. Students were required to read about their assigned group,13 but they were encouraged to draw on their own experiences. On the day of the actual class, there was a discussion of what healthcare providers should know about each major group, drawing on the students' experiences and reading.

Students in this course were required to read an article about teaching pharmacy students how to provide and evaluate service.14 The authors of the article identified 5 criteria for assessing service in pharmacies and various retail stores (being empathetic, reliable, and responsive; providing assurance; and making sure that “tangibles” were appropriate and positive), and these were highlighted in class as appropriate for assessing service-learning work.

In order to gather general information about the students and to assess what they had learned from the course, a survey instrument was administered on the last day of the course. The survey instrument consisted primarily of open-ended questions that required students to articulate specifically what they had learned about a variety of topics addressed in the course (a copy of the survey instrument is available from the author.) Participation in the survey was optional and anonymous and students completing the survey signed consent forms. Someone other than the study director administered the survey instrument so that the study director would not know which students participated in the study and which did not. The design of the study described in this paper was reviewed and approved by the College's Institutional Review Board.

ASSESSMENT

One-hundred fifty students were enrolled in 4 sections of the course at the Worcester campus, and 45 in 2 sections at the Manchester campus in the fall of 2008. Of the 195 students enrolled, 190 gave permission for the data they provided to be used in this study. Seventy-five percent of the students in the course had completed at least a bachelor's degree. The students' average age at enrollment was 26 years, and the ratio of female to male students was 59% to 41%.

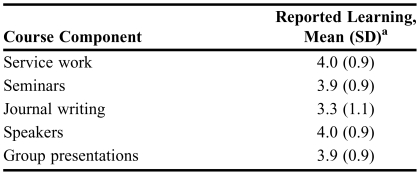

The respondents' answers to questions about how much they had learned from various parts of the course (service work, seminar discussions, journal-writing, guest speakers, group presentations) were compiled and the average answer and standard deviation were calculated for each item. The respondents' answers to the open-ended questions were all read and the most-frequently-reported responses were identified. Because these questions were open ended, the range of possible answers was extensive. Consequently, the fraction of respondents providing any given answer would not be expected to be great. For this reason, any response given by 10% or more of the students was considered noteworthy.

The average responses to the questions about learning from various parts of the course are shown in Table 4. Responses were similar to those seen in the past (unpublished), with relatively high ratings for the learning value of the service work itself, as well as the seminars, the speakers, and the presentations (3.9 - 4.0 on a scale of 1-5), and slightly lower ratings for the journal writing (3.3).

Table 4.

Reported Learning From the 5 Components

aRespondents rated each component on a scale of 1 (nothing) to 5 (very much)

The first 2 open-ended survey questions were broad questions that asked the students to describe either (1) what they learned from their service-learning experience that they could not have learned in the classroom or from reading, or (2) of the things they learned in this or other courses, what their service-learning experience helped them understand better. The responses given by at least 10% of the participants (from most to least frequently mentioned) were: improved communication skills; better understanding of children and teens; better understanding of the importance of empathy; importance of patience; better understanding of diverse people and practices; better understanding of the importance of reliability and professionalism; better understanding of the elderly; better understanding of people different from myself; and better understanding of the value of service. Rather than indicating specifically what the students learned, the responses to these questions indicated the areas of learning of which students were most conscious at the conclusion of the course. The remaining questions asked more specifically about what the students had learned about particular topics.

Since the development of communication skills is one of the course objectives, one survey question asked the students to “describe some of the elements of effective communication.” The most commonly reported answers were: making eye contact; (active) listening; speaking clearly and with adequate volume; knowing (if possible) the person(s) spoken to; speaking at a level the hearer can understand; empathizing with the other person; and the importance of non-verbal communication (body language). While these answers indicate knowledge of these elements (and not necessarily their practice), in year-end evaluations of the students (returned by 110 onsite supervisors), 55% of the supervisors evaluated the students' oral communication skills as excellent, 32% as above average, 13% as good, 1% as fair, and none as needing improvement.

Because of the growing recognition of the importance of cultural competence for healthcare providers, one of the class sessions of the service-learning course introduced students to the topic of cultural diversity. The students in this PharmD program are typically culturally diverse, and in their service-learning work, they encounter diverse populations. (Demographic statistics of the class and of some of the populations served are available from the author.) This diversity makes it possible to draw on the students' backgrounds and experience when treating the topic of cultural competence. In the survey at the end of the course, students were asked to describe 3 things they had learned about cultural competence. The most common answers were: unique healthcare beliefs and practices associated with a culture, avoiding stereotyping or making prejudgments, understanding different customs of various cultures, and working to minimize language barriers, eg, by using pictographs. While some of these comments were general in nature (eg, to treat everyone with respect, to be open-minded), most included fairly specific details (eg, about the use of herbal and natural products, practices such as sharing medications, coining and cupping, the role of the family in the care of an individual).

Approximately 17% of the students in the service-learning course in 2006 worked with seniors in nursing homes, an assisted living facility, an adult day health center, or a senior center. Even those who did not work in these places generally realized the importance of understanding this population. One question on the end-of-course survey instrument asked the students what they had learned from their own or their classmates' service-learning experiences about senior citizens and how to serve them. The most commonly reported answers were the importance of being patient; the importance of empathy/understanding; speaking slowly and with adequate volume; listening carefully; showing respect; and understanding the prevalence of loneliness.

The students in this course worked primarily with at-risk children in a variety of settings (schools, after-school programs, recreation programs, etc). (Demographic statistics for the population served by the students are available from the author.) One question on the post-course survey instrument asked the students to “describe some of the most important factors that may adversely affect children's behavior and performance in school, or their ability to succeed in life.” The most common answers were: poor home life (lack of support); lack of good role models; and peer pressure.

Thirty percent of the students in the course worked with various social service agencies in the local community. Many of them worked with homeless or low-income people. With this in mind, one survey question asked the students to describe some of the factors that led to homelessness. The most commonly reported answers were: alcohol and drug abuse; job loss; financial problems; mental illness; lack of adequate education/training; health problems; inadequate social support; and family problems.

One of the assumptions underlying this course was that community-focused pharmacists should be aware of the wide variety of care-providing organizations in their local community, and therefore, students should become familiar with some of these organizations through their own and their classmates' service-learning work. When asked to identify 2 organizations where students had done community service work, 77% of the respondents were able to do so, usually indicating the type of service provided by the organizations. The remaining respondents identified only 1 organization, mentioned the general types of work done, or did not answer the question.

Students were not told that they were required to memorize the criteria for assessing service; however, the criteria were frequently mentioned in class. Asked on the survey to identify the criteria, 63% of the respondents were able to identify at least some of them and 38% were able to identify all 5.

At the end of the course, supervisors at the service sites were asked to assess the service provided by the students. Of 110 who responded to a written questionnaire, 98% stated that the students had provided regular, high-quality service. The only reservations noted had to do with 2 students' attendance records.

As noted above, 2 instructors directed the service-learning program at the 2 campuses of the College. The Director of Service-Learning spent approximately 25% of his time on this course, and the Service-Learning and Community Outreach Coordinator devoted approximately 25% of his time to the course on the 2 campuses. The organizations in the community devote members' time to the supervision of the students, and in return receive the students' services.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this manuscript was to describe the design of a required service-learning course, and to assess its learning outcomes and their educational relevance. Table 5 lists characteristics of this course, indicating how it meets the ACPE Standards 2007 criteria for a good service-learning experience.15 This course also addresses areas which the Standards 2007 indicate should be addressed in the pharmacy curriculum, including ethics (principles of professional behavior, dealing with ethical dilemmas) and various aspects of professional communication (effective verbal and written interpersonal communication, health literacy, communicating with people from diverse backgrounds, active listening and empathy, assertiveness and problem-solving techniques, cultural influences on communication of health information, group presentation skills, strategies for handling difficult situations).16

Table 5.

Course Characteristics Aligned With Standards 2007

The ACPE Standards 2007 mention “pharmacy as a patient-centered profession.”16 The placement of this service-learning course in the first semester of the first year in the curriculum, concurrently with several basic science courses and Introduction to Pharmaceutical Care, reflects the School's philosophy that caring for others is a priority in the practice of pharmacy and the education of pharmacy students. Before the students have acquired knowledge and skills in the pharmaceutical sciences, they are able to hone their “people skills” in the service-learning course. Later in the curriculum, the students will combine their scientific and clinical knowledge with their skills and experience working with people, in the exercise specifically of pharmaceutical care. Thus, the service-learning course, from the students' first day in the degree program, highlights the people-centered aspect of pharmacy and lays the groundwork for more advance courses later in the curriculum.

The Standards 2007 state that service-learning activities “do not necessarily qualify as introductory pharmacy practice [IPP] experiences,” but that they may “complement the introductory pharmacy practice experiences.”15 The course described and discussed above does this. It addresses many of the educational areas identified by the Standards 2007 and complements other courses in the School's curriculum (especially Introduction to Pharmaceutical Care, Health Care Delivery and Public Health). While it may not qualify as IPP experience, it nevertheless plays an important role in the education of students and is in line with the ACPE Standards 2007.

One of the goals of this course is to expose the students to a variety of important populations in the community. One such group is the senior population. As the population of elder Americans grows, people in this age group are becoming an increasingly large fraction of pharmacists' patients.

Another important population includes the youth in our communities. While most pharmacists may not have extensive contact with children, it is useful for community pharmacists to be aware of the issues faced by children, who like adults need pharmaceutical care. Additionally, some of the lessons learned from working with children, eg, how to explain complex issues in a way that non-experts can understand, are applicable to the practice of pharmacy. There is also a great need in the community to assist children and youth as mentors, tutors, etc.

Another population that students need to understand are those ‘on the fringes’ of our communities. As part of the goal of educating community-focused pharmacists, one objective of the course was to expose the students as much as possible to the needs of underserved populations.

One limitation of this study was that it did not unambiguously demonstrate that the students' knowledge at the end of the course resulted specifically from this course. The areas probed in the end-of-course survey were areas of focus within the course, but some of the knowledge could have come from other courses or experiences, either concurrent with, or prior to, this course. Thus, while the students' learning probably resulted at least in part from this course, some of their knowledge could have resulted from other courses and/or experiences.

To begin to address this limitation, one of the next steps in this investigation will be to compare the learning of students taking a service-learning course to that of a similar group of students not taking any such course. Since all SOP-W/M students are required to enroll in this service-learning course, such a study could not be undertaken internally. Conducting a future study involving a cohort of similar students at an external institution where service-learning is not part of the curriculum is being considered. Such a study might also involve both precourse and postcourse surveys, with the goal of identifying what the students did not know at the beginning of the course, but know at the end of the course (what they learned from it).

Implementing, maintaining, and improving a service-learning-based course requires a commitment of resources on the part of the institution offering the course and the organizations in the community – the community partners – that host/supervise the students. In the case of the present course, the Director of Service-Learning spent approximately 30% of his time for 6 months designing the curriculum and establishing partnerships with more than 30 organizations before the course was offered for the first time. A Service-Learning and Community Outreach Coordinator was hired when the course was expanded to a second campus. As noted above, both of these individuals now spend approximately 25% of their time on this course during 1 semester each year. For the rest of the year, they spend a small but not negligible amount of their time assessing the previous offering of the course, visiting and reviewing service activities with community partners, and preparing for the next offering of the course. Thus, an institutional commitment of resources is essential to initiate and continue to offer such a course.

This course has evolved over the 8 years that it has been offered and will likely continue to do so, with the goal being continuous improvement. For example, the class on cultural diversity was added in 2005 to address an area identified as important in the curriculum. Another example of ongoing improvement is the course journal, a 20-page booklet that provides guidelines for students to reflect on their service and learning. Because of its relatively low rating by students, it was modified after the 2006 offering of the course. (A copy of the journal is available from the author.)

CONCLUSION

This paper has shown that, at the conclusion of the service-learning course, students were able to articulate knowledge in areas addressed by the course, and relevant to the education of pharmacists. Future studies will aim to more clearly identify the role played specifically by the service and learning components of this course in the students' acquisition of this knowledge, but the value of the present study is that it has identified areas of learning probably attributable to this course.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author acknowledges and thanks Drs. Monina Lahoz and Caroline Zeind for their assistance in reading a draft of this manuscript and providing suggestions for improvement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Connors K, Seifer S. A Guide for Developing Community-Responsive Models in Health Professions Education. San Francisco: Community-Campus Partnerships for Health; 1997. Service-Learning in Health Professions Education: What is Service-Learning, and why now? pp. 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Community-Campus Partnerships for Health. Discipline-specific resources. Available at http://depts.washington.edu/ccph/servicelearningres.html#Syllabi. Accessed January 7, 2008.

- 3.Kearney KR. Service-learning in pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68 Article 26. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirwin JL, VanAmbaugh JA, Napoli KM. Service-learning at a camp for children with asthma as part of an advanced pharmacy practice experience. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(3) Article 49. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson JF. A diabetes camp as the service-learning capstone experience in a diabetes concentration. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(6) doi: 10.5688/aj7106119. Article 119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roche VF, Jones RM, Hinman CE, Seoldo N. A service-learning elective in Native American culture, health and professional practice. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(6) doi: 10.5688/aj7106129. Article 129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree. Available at: http://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/ACPE_Revised_PharmD_Standards_Adopted_Jan152006.pdf. Accessed July 13, 2007.

- 8.Kearney KR. Students' self-assessment of learning through service-learning. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(2) Article 29. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eyler JS, Giles DE. Where's the Learning in Service-Learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eyler JS, Giles DE, Stenson CM, Gray CJ. At a Glance: What We Know about the Effects of Service-Learning on College Students, Faculty, Institutions and Communities, 1993-2000. 3rd ed. Campus Compact. Available at: http://www.compact.org/resources/downloads/aag.pdf. Accessed January 8, 2008.

- 11.Weimer M. Learner-Centered Teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conner ML. Andragogy and Pedagogy. Ageless Learner, 1997-2004. Available at: http://agelesslearner.com/intros/andragogy.html. Accessed January 4, 2008

- 13.Galanti GA. Cultural Diversity in Healthcare. Available at: http://ggalanti.com/ Accessed August 3, 2007.

- 14.Indritz MES, Hadsall RS. An active learning approach to teaching service at one college of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 1999;63:126–31. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree, Appendix C (Additional Guidance on Pharmacy Practice Experiences), pages xv-xvi. Available at: http://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/ACPE_Revised_PharmD_Standards_Adopted_Jan152006.pdf. Accessed July 13, 2007.

- 16.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree, Appendix B (Additional Guidance on the Science Foundation for the Curriculum), pages viii-ix. Available at: http://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/ACPE_Revised_PharmD_Standards_Adopted_Jan152006.pdf. Accessed July 13, 2007.