Abstract

Objectives

To determine whether professionalism in pharmacy education is addressed from Bolman and Deal's four-frame leadership model.

Methods

Students (N = 624), faculty (N = 57), preceptors (N = 56), and academic administrators (N = 8) at 6 colleges and schools of pharmacy were surveyed to assess professionalism. Using grounded theory methodology and a constant comparative process, common themes were identified for each question in each group. Themes were assigned to the four-frame model and the data were compared.

Results

Mechanisms of addressing professionalism consistent with all 4 frames of the Bolman and Deal's model were identified. Faculty assessment of student professionalism was significantly lower (P < 0.05) than the student group, preceptors, and administrators.

Conclusions

Mechanisms of addressing professionalism in pharmacy education span all four frames of Bolman and Deal's leadership model. The values students bring into a pharmacy program may play an important role in the process of professional socialization. Faculty members have a tremendous opportunity to enhance student professionalism with their daily verbal and nonverbal interactions with students.

Keywords: leadership, professionalism, qualitative research, pharmacy students, faculty

INTRODUCTION

The goal of pharmacy education consists of preparing pharmacy students with the appropriate skills, attitudes, knowledge, and values to render them competent professionals. The core of the pharmacy curriculum has been based on basic science and clinical knowledge combined with pharmaceutical dispensing and communication skills. The adoption of the doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) degree as the first professional degree heightened expectations of student performance in professional programs. Thus, innovative practice opportunities have recently focused attention on the difficulty of instilling positive attitudes and values in students within pharmacy education. The manner in which specific courses, topics, and instruction address professional values, skills, and behaviors is not well understood. Professional socialization concerns prompted the 2006-2007 American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) Academic Affairs Committee1 to recommend that “AACP should explore mechanisms, such as instruments, on how applicants, students, and faculty are socialized and professionalized to provide guidance to colleges and schools of pharmacy.”

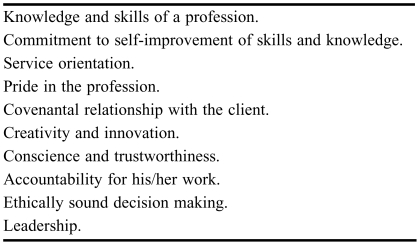

The joint taskforce on professionalism between the American Pharmacists Association Students of Pharmacy (now the Academy of Student Pharmacists) and the AACP Council of Deans white paper2 has described professionalism as “the active demonstration of the traits of a professional.” They go on to define a professional as a member of a profession who displays the 10 traits listed in Table 1. While this definition provides a useful construct to understanding professionalism, Hammer and colleagues3 remind us that this concept is a complex composite of structural, attitudinal, and behavioral fields. There are many definitions of professionalism in the health field today; however, there is no consensus on one definition.3 Regardless, it is imperative for schools and colleges of pharmacy to define professionalism and its attributes to strategically evaluate the progress made by students in this critical area.

Table 1.

Professionalism Traits as Defined by the Joint Task Force of the American Pharmacists Association-Academy of Students of Pharmacy and the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Council of Deans2

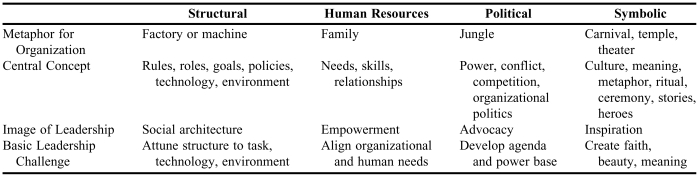

Leadership has been a central theme of the academy for many years. Finding innovative ways to look at challenges presented to the profession is a key strategic issue.4-6 Bolman and Deal have described a new approach to viewing and leading organizations.7 Their four-frame model described in Table 2 views organizations in structural, human resources, political, and symbolic frameworks. Complex human organizations, such as educational institutions and programs, require multiple perspectives or views to understand and operate efficiently. By breaking down challenges and issues into the 4 frames of the model, leaders can understand the problems they face in a broader context. In many cases, managers are more likely to function in only 2 or 3 frames rather than seeing the complete picture. Given an organization-wide problem, the Bolman and Deal four-frame model can provide insight that might not be readily apparent to a manager.7 Theoretically, an organization that is balanced in each of the 4 frames is more efficient at identifying and solving problems. In a similar manner, a model for instilling professionalism in pharmacy students might be most effective if methods from all frames are utilized.

Table 2.

Overview of the Four-Frame Model

Reprinted with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Bolman LG, Deal TE. Reframing Organizations: Artistry, Choice and Leadership. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2007.

The purpose of this research was to carry out a pilot, exploratory study to determine whether professionalism in pharmacy education is addressed from a four-frame leadership model. To investigate this issue, we used qualitative methodology to answer the following questions: (1) How is professionalism addressed in pharmacy education? (2) Which of the 4 frames of the Bolman and Deal's leadership model are addressed? (3) Are there different perspectives among faculty members, students, preceptors, and academic administrators regarding professionalism in pharmacy education and the overall level of student professionalism?

METHODS

This project arose out of the AACP Academic Leadership Fellows Program. The Fellowship program occurred during the 2005-2006 academic year. Student professionalism was selected as the project focus and a thorough review of the literature on professionalism was performed. A search of Medline, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts, and available Internet sites was completed. Key search terms included professionalism, pharmacy, and students. A bibliographic search of retrieved literature identified additional references.

In this pilot study, semi-structured interviews were employed to evaluate professionalism. Grounded theory methodology was used to analyze the interview data.8,9 Grounded theory methodology reflects the concept that the theories emerging from this process are grounded in the data generated in the study. This interview methodology was the most appropriate for exploring new ideas in this area and for evaluating professionalism from multiple viewpoints (ie, students, preceptors, faculty, and administrators).10,11 Additional rationale for using a qualitative approach is the importance that perception plays in the concept of professionalism. Grounded theory allows investigators the ability to focus on the identification, description, and explanation of complex interactions between and among individuals in a given social network. Grounded theory methods have been utilized in the medical, nursing, and health fields since the 1970s.8,12-16

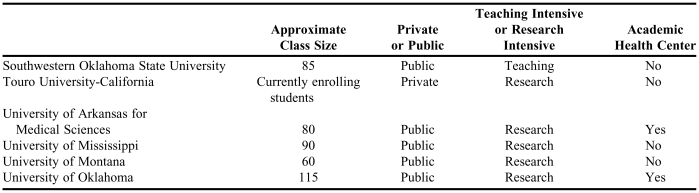

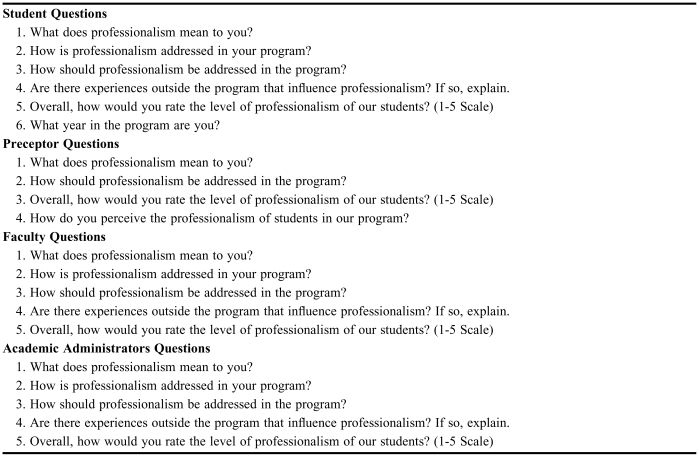

Four sources of information –students, preceptors, faculty members, and academic administrators (dean and provost or chancellor) –were used in a constant comparative process. The study was carried out at 6 diverse colleges of pharmacy (Table 3). Protocols for this project were approved by the institutional review board (or analogous committee) at each of the 6 colleges of pharmacy. Through several meetings, the investigators prepared a series of questions relevant to the issue of professionalism via a collaborative approach (Table 4). Two questions (“How should professionalism be addressed in the program?” and “Overall, how would you rate the professionalism of our students?”) were asked of all participants in a consistent manner, whereas other questions differed slightly in wording among participant groups. Individual interviews (face-to-face and using a survey instrument) were completed with responses documented immediately in writing.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Colleges of Pharmacy Participating in a Study to Identify Perceptions of Professionalism in Pharmacy Using a Four-Frame Leadership Model

Table 4.

Questions Included in a Survey to Identify Perceptions of Professionalism in Pharmacy Using a Four-Frame Leadership Model

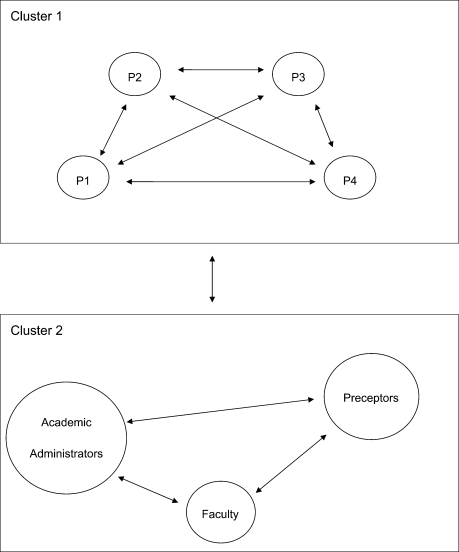

Data analysis began by utilizing the process of constant comparison.14,15 Each investigator performed an independent constant comparison process to maximize theoretical sensitivity.17 The process began by the investigators immersing themselves in the raw data from their own institution to become familiar with and identify recurrent themes and issues. After familiarization was achieved, the data were again examined and compared among the many respondents, as illustrated in Figure 1. In addition to triangulating each of the participants' responses, the investigators combined their data and compared each of the respondent's answers across the individual colleges of pharmacy. After a thorough comparison of the elements of the combined data, key concepts and themes were identified. This was done in concert with the elements of the raw data and the a priori issues and concepts previously identified in the literature. This step in the process involved constant iteration to narrow down the recurrent ideas. The next step in the data analysis involved indexing and charting the various issues into a thematic framework using the four-frame model. Finally, we utilized the 4 frames to make associations between the various views on professionalism from the 4 categories of respondents surveyed.

Figure 1.

Constant comparative methodology applied to current study. Abbreviations: P1 = first year pharmacy students; P2 = second year pharmacy students; P3 = third year pharmacy students; P4 = fourth year pharmacy students; academic administrators = dean and provost or chancellor.

Statistical analysis of quantitative questions on the instrument (Likert scale) was conducted using ANOVA with Fisher protected least-significant difference post-hoc comparisons. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. Differences between the mean values for each group were compared for statistical significance.

RESULTS

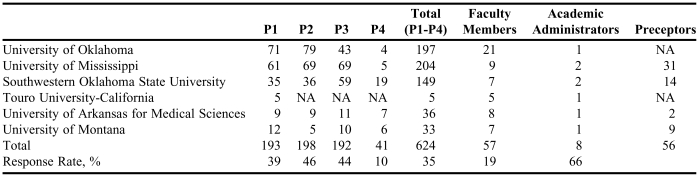

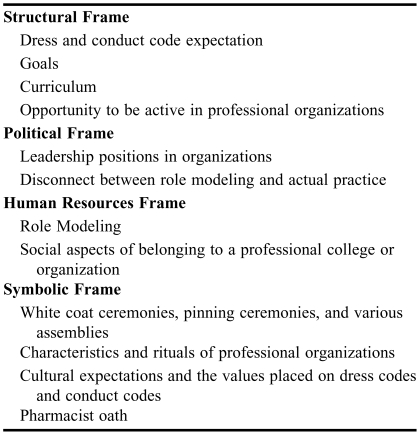

Table 5 lists the absolute number of responses from each of the 6 colleges of pharmacy along with the overall response rates by category. Response rates from preceptors could not be calculated with precision because of unknown denominator values. Table 6 defines the main themes of professionalism within the context of the Bolman and Deal's four-frame model. The structural and symbolic frames are the most familiar issues recognized by all the respondents. The professionalism issues categorized in the human resources and political frames, while not as familiar as the previous 2 frames, may hold important insights to ambiguities observed from student responses. Particularly in the area of role modeling, students expressed a disconnect between expectations of professional behavior in students and the behavior modeled by faculty members, preceptors, and pharmacists in a work environment. This disconnect between what is expected by students and what is being practiced by perceived role models would be analyzed within the political frame in the Bolman and Deal model.

Table 5.

Number of Respondents Participating in a Survey to Identify Perceptions of Professionalism in Pharmacy Using a Four-Frame Leadership Model

Abbreviations: P1= first-year pharmacy students; P2= second year pharmacy students; P3= third year pharmacy students; P4= fourth year pharmacy students; NA= not applicable

Table 6.

Professionalism Themes Viewed in the Four-Frame Context

The 2 key themes from all 4 groups of respondents (students, faculty, preceptors, and administrators) were competency and responsibility. Attitude and ethical standards were common among all groups except academic administrators. Appearance was a theme mentioned by both students and faculty members. Most of the students resisted the idea that professional dress and appearance correlate with true professional behavior. This is reflected in the following 2 statements by students, “It means wearing stuffy clothes and distancing yourself from non-professionals,” and “While working you are not allowed to joke, laugh, or have fun. You have to be serious. You can't wear comfortable clothing to help you relax either.”

The themes that arose from responses to the question “How is professionalism addressed in your program?” are given in Table 6. Each theme was assigned to the most appropriate frame of the Bolman and Deal model as shown. Many themes readily fit into structural, human resource, or symbolic frames. In contrast, few themes emerged that readily fit into the political frame other than “leadership roles in professional or student organizations.” Readily apparent in these data was a disconnect between faculty members who indicated that role modeling was an important mechanism of addressing professionalism in their programs and students who suggested that faculty members were not serving as appropriate role models for professionalism. We fit these contradictory themes in the political frame reflecting conflict as suggested by the Bolman and Deal model.

One of the student trends observed was the consistency of response by the student regardless of their year in the program. First-year students and fourth-year students provided similar themes and these themes were more closely linked to an individual school than to the student's progression in the program. This may reflect the emphasis a school places on particular issues (ie, white coat ceremony, honor code, dress code).

In response to the question “How should professionalism be addressed in your program?” similar themes emerged from students, faculty members, and administrators. Again, all groups suggested that faculty members should demonstrate professionalism through role modeling. A student comment illustrates this theme: “Many professors speak of professionalism, but few seem to exhibit the things they talk about.” Faculty members seemed aware that they are to set an example of professionalism. When faculty members responded to the question of how professionalism should be addressed, common answers included “faculty role models” or “better faculty role models” or “by example.”

All respondents indicated that professionalism should be addressed throughout the curriculum. Students early in the program expressed a desire for more interactions, examples, applications, and feedback as a way to improve professionalism and better understand what it means to be a professional. Interestingly, while all groups indicated that professionalism was being addressed at their institution through symbolic frame activities (eg, professionalism ceremonies), only the administrators thought that more emphasis should be placed on symbolism.

One theme that emerged from responses to the question “Are there experiences outside the program that influence professionalism?” is the role that family and early nurturing play in the development of values. This theme was common across the spectrum of respondents and reflected in faculty statements such as “If we have to teach this, did we pick the right people as students?” and student statements such as “….dressing professionally does not make you professional—that comes from within.” These statements suggest that values such as good attitude, proper behavior, compassion, appropriate dress, and respect may be first learned during the formative years of a student's life. However, these values can certainly be reinforced, strengthened, and improved with additional training, education, and appropriate role modeling.

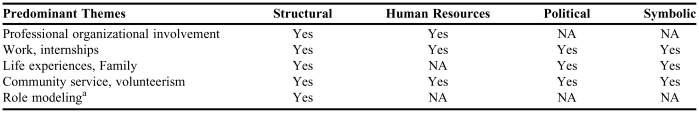

External influences on student professionalism emerged in several major recurring themes from all respondents. These themes clearly pointed to several major external influences: professional organizations, work/internships, life experiences, community service, and volunteerism. Surprisingly, only faculty members pointed to the influence of external role models as having a significant impact on student professionalism. The themes that emerged from responses to this question spanned the 4 Bolman and Deal frames where, for example, “work/internship” experiences included aspects of human resource, political, structural, and symbolic frames (Table 7). Thus, for many themes that emerged from the responses, the frames were not mutually exclusive.

Table 7.

Collective Set of Themes Emerging From a Framework Analysis of the Question, “Are there experiences outside the program that influence professionalism?”

Abbreviations: NA=Not Applicable

aIdentified by faculty members only

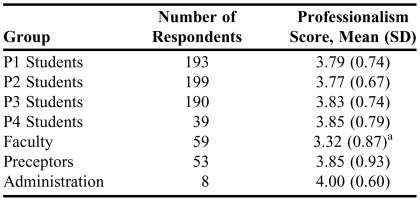

Table 8 illustrates the professionalism scores provided by students, faculty members, preceptors, and administrators in response to the question, “Overall, how would you rate the level of professionalism of our students?” Specific responses (mean ± standard deviation) for each group were: first-year pharmacy students = 3.8 ± 0.7, second-year pharmacy students = 3.8 ± 0.7, third-year pharmacy students = 3.8 ± 0.7, fourth-year pharmacy students = 3.8 ± 0.8, faculty members = 3.3 ± 0.9, preceptors = 3.8 ± 0.9, and academic administrators = 4.0 ± 0.6. With regard to group means, students, preceptors, and administrators ranked student professionalism with a score of 3.8 on a 1 to 5 scale, with no significant differences in ratings among these groups. Faculty members' perceptions of student professionalism was significantly lower than that of the students, preceptors, and academic administrators.

Table 8.

Professionalism Rating Scores Provided by Students, Faculty, Preceptors, and Academic Administrators in Response to the Question “How would you rate the level of professionalism of our students?” (Scale of 1-5 with 5 being highest).

aP < 0.05 versus each student group, preceptors and academic administrators (ANOVA with Fisher PLSD post-hoc analysis)

DISCUSSION

Professionalism in pharmacy is important and developing professional values and traits in pharmacy students is a complex and dynamic process. It is complicated by a lack of consensus on which subjects, skills, or activities define what it means to be a professional. A wide range of skills, knowledge, behaviors, and observations appear to be involved. The results of this study indicate that the Bolman and Deal four-frame model can be used to evaluate and analyze professionalism in pharmacy education.

Professionalism components can be found in each of the 4 frames. However, there does not appear to be equal weighing of the themes among the 4 frames. The overwhelming professionalism themes belonged to the structural or symbolic frames. These included dress and conduct codes (structural) and the white coat and other ritual ceremonies (symbolic). However, when asked how professionalism should be addressed in the curriculum, students indicated a need for more interactions and applications which primarily reside in the political and human resource frames. If a balance among components within the model is ideal, these 2 frames may not be receiving enough attention as there appeared little evidence of political advocacy or an agenda in the responses. The negative connotation of student comments on role modeling is also of concern. Students, faculty members, preceptors, and administrators all agreed role models were important, but students sometimes felt that expectations and traits expected of them were not being exhibited by the perceived role models (faculty members and preceptors). Regardless, faculty members are viewed as role models, and their behaviors and traits are closely watched by students. Additionally, the empowerment and collegial relationship in the human resource frame may be underutilized at this time. This may be manifested in the way students in the first few years are sometimes restricted to “shadowing” or watching experiential patient activities. Only in the fourth year are students afforded more latitude to exhibit and practice professional skills and traits. Elements associated with a particular frame, such as the symbolic white coat ceremony or dress codes, need to be linked with other frames of reference for that activity to be truly connected and conceptualized as professional behavior. This appears to be the case at times with dress and conduct codes, where the purpose and intent of that activity is not appreciated by students. The Bolman and Deal model may provide a framework in which faculty members and preceptors can examine their current educational strategies, categorize these strategies into appropriate frames, and identify areas on which to focus when attempting to improve student professionalism.7

Sylvia surveyed the professionalism efforts of 52 colleges and schools of pharmacy using a 62-item questionnaire.18 Symbolic frame activities (white coat ceremony and distribution of the Oath of the Pharmacist) along with structural frames (student involvement in professional organizations) were present in more than 90% of the schools that responded. The survey instrument used by Sylvia was dominated by structural and symbolic frame items, a small number of human resources frame items, and few items that could be considered in the political frame. The several professionalism instruments that have been developed to assess student professionalism also follow this general pattern.19-21 Hammer's review of professionalism in pharmacy education details an exhaustive discussion of the factors involved in professional student development.3

Several issues raised in this study reinforce these principles. First, our data highlight the important role that values play in professionalism. Values developed early in life and brought into pharmacy school by the student may be a more important factor than previously acknowledged. Secondly, role modeling by faculty members, preceptors, and pharmacists in a work environment is well appreciated in the literature. Our data would emphasize the crucial role that faculty members play in modeling professionalism to students. As important as positive role modeling is for faculty members, our results suggest that the disillusionment developed by students from negative faculty role modeling might be underestimated in the literature.

Duncan-Hewitt describes the development of a professional using a staged approach that was derived using grounded theory methodology.22 The 6 stages, ranging from F0 to F5, illustrate an educationally oriented model of increasing cognitive/moral development. While describing the key role of mentoring in the progression of student development through these stages, Duncan-Hewitt writes, “…a significant proportion of the faculty have no interest in that role [mentoring]. In fact, a good number believe that such mentoring is not their responsibility.” Our data reinforce some of these perceptions and point to the key role faculty members can play in the professional growth of students.

Bumgarner and colleagues describe a unique approach to early instillation of professional values.23 These investigators provided a booklet of 4 short stories that emphasized the essential qualities of professionalism to all incoming students at the McWhorter School of Pharmacy. The students were then divided in small groups for discussion of the major themes of the readings. Through a survey instrument, they were able to show an increased awareness of professional concepts. Perhaps more attention can be directed to screening students who exhibit underlying elements of professionalism such as good attitude, appropriate behavior, respect, and compassion. Admitting students with these attributes may significantly improve our efforts to address professional values with students as they progress through the curriculum. Whether this can be done using a preadmission survey or personal interviews and background checks is not known. Our data suggest that this area is perhaps not receiving adequate emphasis by the academy and would benefit from additional investigation. As health care becomes more complex, a higher level of professionalism will be required of our pharmacy graduates. Continued investigation by the academy on methods for improving professionalism is essential.

Our investigation of professionalism is subject to certain limitations. First, this study examines professionalism from an organizational framework using the four-frame model. Other models or perspectives may provide different insights. Second, we utilized a geographically disperse convenience sample of student and faculty responses from 6 academic institutions. Because of our sampling method and the large number of schools and colleges of pharmacy currently operating in the United States, our sample may not be representative of all institutions. Finally, the potential errors of interrater reliability and theme development were minimized by the constant comparison process and re-examination of responses by multiple investigators.

CONCLUSION

Professionalism is an important topic for the future of healthcare. Current mechanisms of addressing professionalism in pharmacy education span all 4 frames of Bolman and Deal's leadership model. The structural frame includes student dress codes and the academic curriculum. The human resources frame includes the key issue of faculty role modeling. Leadership in student organizations is a component of the political frame. Finally, the white coat ceremony represents the symbolic frame. Faculty members have a tremendous opportunity to enhance student professionalism with their daily verbal and nonverbal interactions with students. However, faculty members should be consistent in addressing and interconnecting humanistic and political frames to maximize their effectiveness as professional role models for students.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy for supporting the Academic Leadership Fellows Program and the Deans of the involved colleges for their encouragement and help with this project.

Presented in part at the 107th Annual Meeting of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, San Diego, CA, in July 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bradberry JC, Droege M, Evans RL, etal. Curricula then and now: an environmental scan and recommendations since the commission to implement change in pharmaceutical education. Report of the 2006-2007 American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, Academic Affairs Committee. 2007 Available at: http://www.aacp.org/Docs/AACPFunctions/Governance/8442_GettingtoSolutionsinInterprofessionalEducationfinal.pdf Accessed on August 4, 2007.

- 2.American Pharmacists Association-Academy of Students of Pharmacy and the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Council of Deans. White paper on pharmacy student professionalism. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2000;40:96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammer DP, Berger BA, Beardsley RS, Easton MR. Student professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(3) Article 96. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin A, Altiere R, Harris W. Leadership: the nexus between challenge and opportunity: Reports of the 2002-2003 Academic Affairs, Professional Affairs, and Research and Graduate Affairs Committees. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(3) Article S05. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wells BG. Leadership for ethical decision making. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(1) Article 3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wells BG. Leadership for reaffirmation of professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2002;66:334–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolman LG, Deal TE. Reframing Organizations: Artistry, Choice and Leadership. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmoll BJ. Bork CE. Research in Physical Therapy. Philadelphia: Williams and Wilkins; 1992. Qualitative research. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strauss A, Corbin J. Grounded theory methodology: an overview. In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Britten N. Qualitative research: qualitative interviews in medical research. Br Med J. 1995;311:251–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6999.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar S, Little P, Britten N. Why do general practitioners prescribe antibiotics for sore throat? Grounded theory interview study. Br Med J. 2003;326:138. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7381.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morse JM. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1990. Qualitative Nursing Research. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mays N, Pope C. Assessing quality in qualitative research. Br Med J. 2000;320:50–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Analyzing qualitative data. Br Med J. 2000;320:114–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer J. Using qualitative methods in health related action research. Br Med J. 2000;320:178–81. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7228.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glaser BG. Theoretical Sensitivity: Advances in the Methodology of Grounded Theory. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sylvia LM. Enhancing professionalism of pharmacy students: results of a national survey. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(4) Article 104. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duke LJ, Kennedy WK, McDuffie CH, Miller MS, Sheffield MC, Chisholm MA. Student attitudes, values, and beliefs regarding professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(5) Article 104. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chisholm MA, Cobb H, Duke L, McDuffie C, Kennedy WK. Development of an instrument to measure professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(4) doi: 10.5688/aj700485. Article 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hammer DP, Mason HL, Chalmers RK, Popovich NG, Rupp MT. Development and testing of an instrument to assess behavioral professionalism of pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64:141–51. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duncan-Hewitt W. The development of a professional: reinterpretation of the professionalization problem from the perspective of cognitive/moral development. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(1) Article 6. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bumgarner GW, A Spies AR, Asbill CS, Prince VT. Using the humanities to strengthen the concept of professionalism among first-professional year pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(2) doi: 10.5688/aj710228. Article 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]