Abstract

Suicidal behavior is a leading cause of injury and death worldwide. Information about the epidemiology of such behavior is important for policy-making and prevention. The authors reviewed government data on suicide and suicidal behavior and conducted a systematic review of studies on the epidemiology of suicide published from 1997 to 2007. The authors' aims were to examine the prevalence of, trends in, and risk and protective factors for suicidal behavior in the United States and cross-nationally. The data revealed significant cross-national variability in the prevalence of suicidal behavior but consistency in age of onset, transition probabilities, and key risk factors. Suicide is more prevalent among men, whereas nonfatal suicidal behaviors are more prevalent among women and persons who are young, are unmarried, or have a psychiatric disorder. Despite an increase in the treatment of suicidal persons over the past decade, incidence rates of suicidal behavior have remained largely unchanged. Most epidemiologic research on suicidal behavior has focused on patterns and correlates of prevalence. The next generation of studies must examine synergistic effects among modifiable risk and protective factors. New studies must incorporate recent advances in survey methods and clinical assessment. Results should be used in ongoing efforts to decrease the significant loss of life caused by suicidal behavior.

Keywords: psychiatry; public health; risk factors; self-injurious behavior; suicide; suicide, attempted

Introduction

Suicide is an enormous public health problem in the United States and around the world. Each year over 30,000 people in the United States and approximately 1 million people worldwide die by suicide, making it one of the leading causes of death (1–3). A recent report from the Institute of Medicine (National Academy of Sciences) estimated that in the United States the value of lost productivity due to suicide is $11.8 billion per year (4). Reports from the World Health Organization (WHO) indicate that suicide accounts for the largest share of the intentional injury burden in developed countries (5) and that suicide is projected to become an even greater contributor to the global burden of disease over the coming decades (6, 7). The seriousness and scope of suicide has led both the WHO (8) and the US government (2, 3) to call for an expansion of data collection on the prevalence of and risk factors for suicide and nonfatal suicidal behavior to aid in the planning of public-health strategies and health-care policies and in the monitoring of behavioral responses to policy changes and prevention efforts.

Addressing these calls, in this paper we provide a review of the epidemiology of suicidal behavior and extend earlier reviews in this area (9–21) in two important ways. First, we provide an update on the prevalence of suicidal behavior over the past decade. The socioeconomic and cultural factors with which suicidal behavior is associated, such as the quality and quantity of mental health services, have changed dramatically (22, 23), making it important to examine whether and how the prevalence of suicidal behavior has changed over time. Second, most prior reviews have focused on a specific country (e.g., the United States), subgroup (e.g., adolescents), or behavior (e.g., suicide attempts). We review data from multiple countries, on all age groups, and on different forms of suicidal behavior, providing a comprehensive picture of the epidemiology of suicidal behavior. Moreover, given recent technologic developments in injury surveillance systems (24), as well as the recent completion of several large-scale epidemiologic studies examining the cross-national prevalence of suicidal behavior (25–28), an updated review of this topic is especially warranted at this time.

Terminology and definitions in suicide research

We use the terminology for and definitions of suicidal behavior outlined in recent consensus papers on this topic (29–32). We define suicide as the act of intentionally ending one's own life. Nonfatal suicidal thoughts and behaviors (hereafter called “suicidal behaviors”) are classified more specifically into three categories: suicide ideation, which refers to thoughts of engaging in behavior intended to end one's life; suicide plan, which refers to the formulation of a specific method through which one intends to die; and suicide attempt, which refers to engagement in potentially self-injurious behavior in which there is at least some intent to die. Most researchers and clinicians distinguish suicidal behavior from nonsuicidal self-injury (e.g., self-cutting), which refers to self-injury in which a person has no intent to die; such behavior is not the focus of this review (33–35).

We first review data on the current rates of and recent trends in suicide and suicidal behavior in the United States and cross-nationally. Next we review data on the onset, course, and risk and protective factors for suicide and suicidal behavior. Finally, we summarize data from recent suicide prevention efforts and conclude with suggestions for future research.

Materials and Methods

Main data sources

Suicide

Data on annual suicide mortality in the United States are maintained by the National Vital Statistics System of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and were retrieved for this review using the Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) (36). In examining recent time trends, we examined rates of suicide in the United States from 1990–2005, the most recent data currently available. Suicide data for many other countries are maintained by the WHO (8). We included information in this review from a wide range of countries and for those countries with the highest reported rates of suicide, but we did not include data for every country because of space constraints. Cross-national variability in the most recent year for which suicide data were available precluded an analysis of recent trends at the same level of detail as that for the United States.

Suicidal behavior

The CDC also maintains data on the estimated rate of nonfatal self-injury based on a national surveillance system of injuries treated in US hospital emergency departments (the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System) (37). We reviewed these data to estimate the rate of nonfatal self-injury in the United States. Although these data provide valuable information about the scope of this problem, they have three notable limitations: They lack precision in that they do not distinguish between suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injury; they do not provide data on characteristics or risk or protective factors; and they fail to capture self-injury not treated in US hospital emergency departments. In order to address these limitations, we also obtained data on the prevalence and characteristics of nonfatal suicidal behavior in the United States and other countries via a systematic electronic search of the recent peer-reviewed literature (1997–2007). We searched the US National Library of Medicine's PubMed electronic database using the title and abstract search terms “suicide,” “suicidal behavior,” and “suicide attempt” and requiring the term “epidemiology” or “prevalence.” This search yielded 1,052 abstracts, which we reviewed individually. We used these articles to inform the review if the authors reported the prevalence of suicide (n = 28) or suicidal behavior (n = 65) within some well-defined population, reported on risk/protective factors or prevention programs (n = 132), or provided a review of studies on one or more of the aforementioned topics (n = 102). Excluded were studies with small sample sizes (<100; n = 73), studies for which the full article was not available in English (n = 108), studies of narrowly defined subpopulations (e.g., specific clinical samples) or irrelevant topics (e.g., cellular suicide) (n = 493), and studies that did not provide a specific measure of one of the suicidal behaviors outlined above (n = 51). When we identified multiple articles reporting on the same data source (e.g., the CDC Youth Risk Behavior Survey), we used only the primary or summary report to avoid redundancy.

Results

Suicide in the United States

Current rates

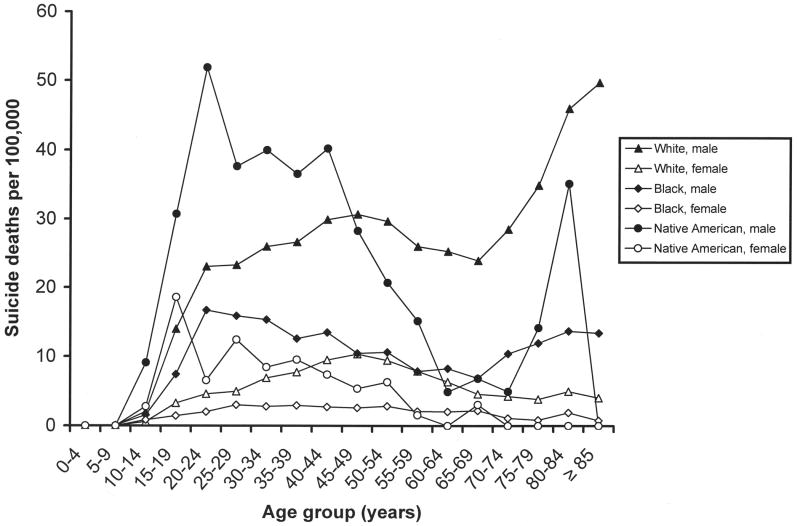

In the United States, suicide occurs among 10.8 per 100,000 persons, is the 11th-leading cause of death, and accounts for 1.4 percent of all US deaths (36). A more detailed examination of the data by sex, age, and race/ethnicity reveals significant sociodemographic variation in the suicide rate. As figure 1 illustrates, there are no group differences until mid-adolescence (ages 15–19 years), at which time the rate among males increases dramatically relative to the rate among females. The rise for males is greatest among Native Americans/Alaskan Natives, increasing more than fivefold during adolescence and young adulthood, from 9.1 per 100,000 (ages 10–14 years) to 51.9 per 100,000 (ages 20–24 years). The rate for Native American/Alaskan Native males declines during middle adulthood before peaking again during older age. Non-Hispanic White males also have a sharp increase during adolescence and young adulthood (from 2.0/100,000 at ages 10–14 years to 23.0/100,000 at ages 20–24 years) and a second one from ages 65–69 years (23.9/100,000) to age 85 years or more (49.7/100,000). The rates for women are lower and virtually nonoverlapping with those of men, with two exceptions being suicide among Native American/Alaskan Native women during adolescence (ages 10–19 years) and suicide for White women during middle age (ages 55–59 years). Suicide rates for people of Hispanic and Asian race/ethnicity, not presented in figure 1 because of space constraints, were generally similar to those for Black males and females.

FIGURE 1.

Numbers of suicide deaths in the United States, by race/ethnicity, sex, and age group, 2005. Data were obtained from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) (36). Data points based on fewer than 20 deaths per cell may be unreliable. These include those for persons under age 10 years for all groups, those for persons aged ≥80 years for Black males, those for persons aged 10–14 years and ≥55 years for Black females, those for persons aged 10–14 years and ≥45 years for Native American/Alaskan Native males, and all points except those for persons aged 10–14 years for Native American/Alaskan Native females.

Recent trends

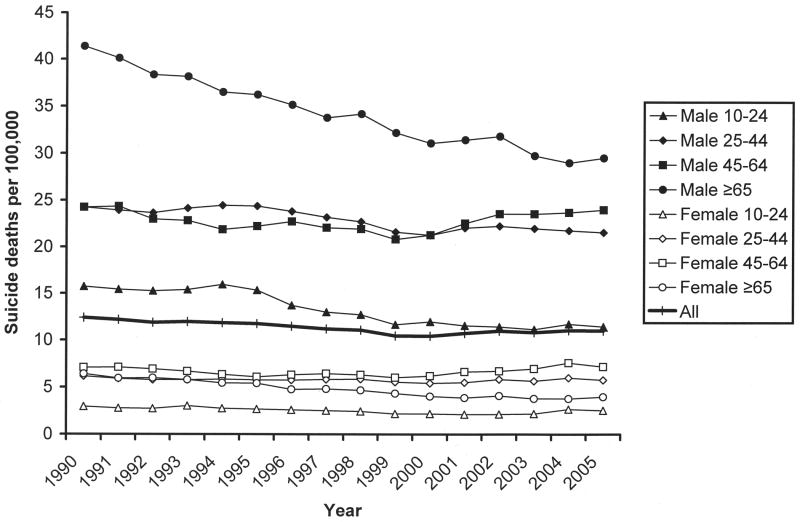

Figure 2 depicts recent trends (1990–2005) in rates of suicide in the United States, with separate lines plotted by sex (male/female) and age group (10–24, 25–44, 45–64, or ≥65 years). Suicide rates stratified by race/ethnicity did not change during this time period and so were not included for ease of presentation. As the figure shows, the suicide rate is consistently higher for males than for females. Substantive decreases have occurred for elderly males (ages ≥65 years), who show a decrease from 41.4 per 100,000 to 29.5 per 100,000, and for young males (ages 10–24 years), who show a decrease from 15.7 per 100,000 to 11.4 per 100,000. The overall US suicide rate decreased from 12.4 per 100,000 to 11.0 per 100,000 (an 11.1 percent decrease) during this time.

FIGURE 2.

Numbers of suicide deaths in the United States, by sex, age group, and year, 1990–2005. Data were obtained from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) (36).

Cross-national suicide rates

Current rates

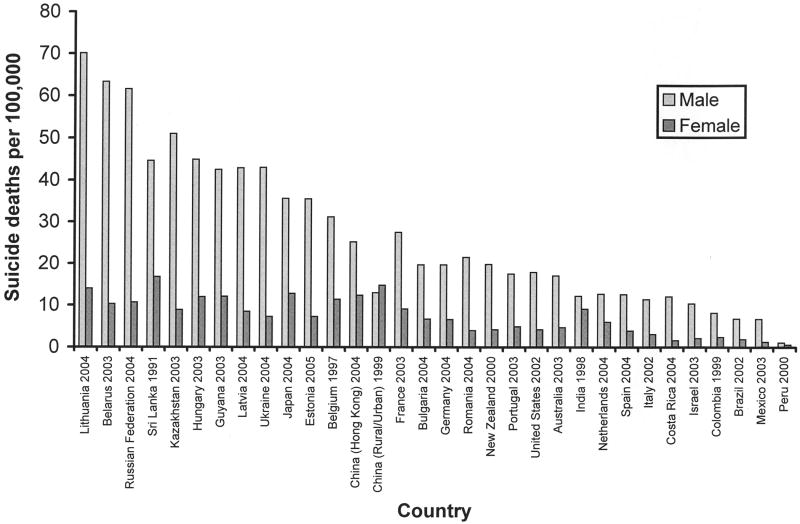

International data from the WHO indicate that suicide occurs in approximately 16.7 per 100,000 persons per year, is the 14th-leading cause of death worldwide, and accounts for 1.5 percent of all deaths (8). As figure 3 illustrates, suicide rates vary significantly cross-nationally. In general, rates are highest in Eastern Europe and lowest in Central and South America, with the United States, Western Europe, and Asia falling in the middle. Despite the wide variability in rates, there is a consistently higher rate among men than among women, with men more often dying by suicide at a ratio of 3:1–7.5:1. Two notable exceptions are India and China, where there are no clear sex differences. The male:female ratio is 1.3:1 in India, 0.9:1 in mainland China, and 2.0:1 in Hong Kong. The reason for the absence of a sex difference in India and mainland China is not known, but it has been suggested that the lower social status of females in the context of disempowering circumstances and the more lethal methods used in these countries, such as self-burning in India (38) and ingestion of pesticides in China (39), may account for this pattern. Given that India and China alone constitute nearly half of the world's population, this “atypical” ratio may well represent a typical pattern when considered on the basis of the global population.

FIGURE 3.

Numbers of suicide deaths in numerous nations, for the most recent year available. Data were obtained from the World Health Organization (8).

Recent trends

Definitive data do not exist on worldwide trends in suicide mortality because of cross-national differences in reporting procedures and data availability. The WHO has maintained cross-national data on suicide mortality since 1950; however, there are inconsistencies in reporting by individual country, with only 11 countries providing data in 1950, 74 in 1985, and 50 in 1998. Moreover, the fact that some governments have treated suicide as a social or political issue rather than a health problem may have diminished the validity of earlier data and resulting estimates. Given these inconsistencies, it is difficult to generate an accurate cross-national estimate of trends. Nevertheless, the data maintained by the WHO suggest that the global rate of suicide increased between 1950 and 2004, especially for men (40), and data-based projections suggest that the number of self-inflicted deaths will increase by as much as 50 percent from 2002 to 2030 (7). Given the inconsistencies in data sources both within and across countries (40–42), though, a definitive picture of long-term trends in global suicide death cannot be formed.

Suicidal behavior in the United States

Current rates

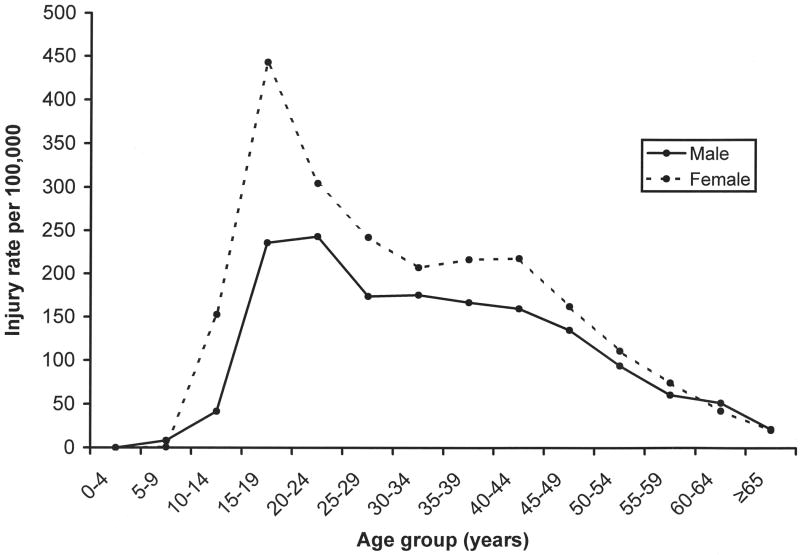

Figure 4 presents CDC data (37) on nonfatal self-injury in the United States for 2006, by age group. There is a significant increase in risk of nonfatal self-injury (both suicidal and nonsuicidal in nature) during adolescence and young adulthood which then decreases monotonically throughout adulthood. In contrast to suicide mortality, rates of nonfatal self-injury are consistently higher among females. Data from our systematic review suggest that for US adults (ages ≥18 years), the lifetime prevalence of suicide ideation is 5.6–14.3 percent, with an interquartile range (IQR) of 7.9–13.9. For suicide plans, the lifetime prevalence is 3.9 percent, and for suicide attempts it is 1.9–8.7 percent (IQR, 3.0–5.1) (see table 1 for studies). Twelve-month prevalence estimates are in the range of 2.1–10.0 percent (IQR, 2.4–6.7) for suicide ideation, 0.7–7.0 percent (IQR, 0.7–5.5) for suicide plans, and 0.2–2.0 percent (IQR, 0.3–1.3) for suicide attempts, with higher rates for younger adults and females (table 1). Some of the variation in rates is probably due to sample selection (e.g., a high rate of attempts in the study including only Native Americans) and variability in the methods used to assess suicidal behaviors. For instance, questions asking about “thoughts of death” generate higher prevalence estimates for suicide ideation than questions asking about “seriously considering suicide” (43), and questions requiring endorsement of an intent to die from self-injury yield lower estimates of suicide attempts than questions asking simply whether a person has made a “suicide attempt” (34).

FIGURE 4.

Rates of nonfatal self-injury in the United States, by sex and age group, 2006. Data were obtained from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) (37). Data points for persons under age 10 years were based on relatively few cases and may be unreliable.

Table 1.

Results from key studies on the prevalence of suicidal behavior, 1997–2007

| Study (reference no.) | Location and study design | Sample (ages of participants) | Prevalence estimate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| US studies—adults (n = 11) | |||

| Kessler et al., 1999 (47) | Nationally representative sample | 5,877 adults (15–54 years) | Lifetime ideation: 13.5 |

| Lifetime plans: 3.9 | |||

| Lifetime attempts: 4.6 | |||

| Dube et al., 2001 (207) | Primary care clinic in San Diego, California | 17,337 adults (mean age = 57 years; standard deviation, 15.3) | Lifetime attempts: 3.8 |

| Kuo et al., 2001 (208) | Baltimore, Maryland, community population | 1,920 adults for this follow-up study (at baseline, ≥18 years) | Lifetime ideation: 5.6 |

| Lifetime attempts: 1.9 | |||

| Ialongo et al., 2002 (209) | Baltimore, Maryland, metropolitan area | 1,157 African Americans (19–22 years) | Lifetime ideation: 14.3 |

| Lifetime attempts: 5.3 | |||

| 6-month ideation: 1.9* | |||

| 6-month attempts: 0.4* | |||

| Garroutte et al., 2003 (149) | Northern Plains reservations | 1,456 American Indian tribal members (15–57 years) | Lifetime attempts: 8.7 |

| Joe et al., 2006 (210) | Nationally representative sample | 5,181 African Americans (≥18 years) | Lifetime ideation: 11.7 |

| Lifetime attempts: 4.1 | |||

| 12-month ideation: 2.1 | |||

| 12-month attempts: 0.2 | |||

| Nock and Kessler, 2006 (34) | Nationally representative sample | 5,877 adults (15–54 years) | Lifetime gestures (no intent): 1.9* |

| Lifetime attempts (with intent): 2.7 | |||

| Lifetime total attempts: 4.6 | |||

| Fortuna et al., 2007 (211) | Latino ethnic subgroups | 2,554 Spanish- and English-speaking members of Latino ethnic subgroups | Lifetime ideation: 10.1 |

| Lifetime attempts: 4.4 | |||

| Brener et al., 1999 (212) | College student population | 4,609 undergraduate and graduate students (≥18 years) | 12-month ideation: approximately 10 |

| 12-month plans: approximately 7 | |||

| 12-month attempts: approximately 2 | |||

| Kessler et al., 2005 (22) | Nationally representative sample | 9,708 adults (18–54 years), surveyed either between 1990 and 1992 (T1; n = 5,388) or between 2001 and 2003 (T2; n = 4,320) | 12-month ideation (T1): 2.8 |

| 12-month ideation (T2): 3.3 | |||

| 12-month plans (T1): 0.7 | |||

| 12-month plans (T2): 1.0 | |||

| 12-month gestures (T1): 0.3 | |||

| 12-month gestures (T2): 0.2 | |||

| 12-month attempts (T1): 0.4 | |||

| 12-month attempts (T2): 0.6 | |||

| Borges et al., 2006 (57) | Nationally representative sample | 5,692 adults (≥18 years) | 12-month ideation: 2.6 |

| 12-month plans: 0.7 | |||

| 12-month attempts: 0.4 | |||

| US studies—adolescents (n = 6) | |||

| Alaimo et al., 2002 (213) | Nationally representative sample | 754 adolescents (15–16 years) | Lifetime ideation: 19.8 |

| Lifetime attempts: 4.6 | |||

| Eisenberg et al., 2003 (214) | Minneapolis/St. Paul, Minnesota, metropolitan area | 4,746 adolescents (grades 7–12) | Lifetime ideation: 24.0 |

| Lifetime attempts: 8.8 | |||

| Waldrop et al., 2007 (215) | Household probability sample | 3,906 adolescents (12–17 years) | Lifetime ideation: 23.3 |

| Lifetime attempts: 3.1 | |||

| O'Donnell et al., 2004 (156) | Economically disadvantaged neighborhoods in Brooklyn, New York | 879 urban adolescents (16–17 years) | 12-month ideation: 15.0 |

| 12-month plans: 12.6 | |||

| 12-month attempts: 10.6 | |||

| 12-month multiple attempts: 4.3 | |||

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007 (45) | Nationally representative sample (biannually 1991–2005, Youth Risk Behavior Survey) | Adolescents (grades 9–12) from whom data were biannually collected between 1991 (n = 12,272) and 2005 (n = 13,953) | 12-month ideation (1991): 29.0 |

| 12-month ideation (1993): 24.1 | |||

| 12-month ideation (1995): 24.1 | |||

| 12-month ideation (1997): 20.5 | |||

| 12-month ideation (1999): 19.3 | |||

| 12-month ideation (2001): 19.0 | |||

| 12-month ideation (2003): 16.9 | |||

| 12-month ideation (2005): 16.9 | |||

| 12-month plans (1991): 18.6 | |||

| 12-month plans (1993): 19.0 | |||

| 12-month plans (1995): 17.7 | |||

| 12-month plans (1997): 15.7 | |||

| 12-month plans (1999): 14.5 | |||

| 12-month plans (2001): 14.8 | |||

| 12-month plans (2003): 16.5 | |||

| 12-month plans (2005): 13.0 | |||

| 12-month attempts (1991): 7.3 | |||

| 12-month attempts (1993): 8.6 | |||

| 12-month attempts (1995): 8.7 | |||

| 12-month attempts (1997): 7.7 | |||

| 12-month attempts (1999): 8.3 | |||

| 12-month attempts (2001): 8.8 | |||

| 12-month attempts (2003): 8.5 | |||

| 12-month attempts (2005): 8.4 | |||

| King et al., 2001 (216) | Four geographically and ethnically diverse regions (Connecticut, Georgia, New York, and Puerto Rico) | 1,285 adolescents (9–17 years) | 6-month ideation (among persons with no lifetime attempts): 5.2* |

| 6-month attempts: 3.3* | |||

| International studies—adults (n = 26) | |||

| Statham et al., 1998 (63) | Australia, community (twin) sample | Adult twins (women, 27–89 years; men, 28–85 years) from an Australian twin panel first surveyed in 1980–1982 (n = 5,995) | Lifetime ideation (males): 23.8 |

| Lifetime ideation (females): 22.2 | |||

| Lifetime plans (males): 5.7 | |||

| Lifetime plans (females): 6.2 | |||

| Lifetime attempts (males): 1.7 | |||

| Lifetime attempts (females): 3.0 | |||

| Kebede et al., 1999 (217) | Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, nationally representative sample | 10,203 adults (≥15 years) | Lifetime attempts: 0.9 |

| Current ideation: 2.7* | |||

| Akyuz et al., 2005 (218) | Central Turkey, nationally representative sample | 628 women (18–65 years) | Lifetime attempts: 4.5 |

| Kjoller and Helweg-Larsen, 2000 (219) | Denmark, nationally representative sample | 1,362 adults (≥16 years) | Lifetime attempts: 3.4 |

| 12-month ideation: 6.9 | |||

| 12-month attempts: 0.5 | |||

| Ramberg and Wasserman, 2000 (220) | Stockholm, Sweden, general population and mental health-care staff | 1,010 mental health-care staff (19–64 years); 8,171 persons from the general population (20–64 years) | Lifetime ideation (mental health-care staff): 42.8* |

| Lifetime ideation (general population): 20.3 | |||

| Lifetime attempts (mental health-care staff): 4.8* | |||

| Lifetime attempts (general population): 3.6 | |||

| 12-month ideation (mental health-care staff): 7.7* | |||

| 12-month ideation (general population): 7.3 | |||

| 12-month attempts (mental health-care staff): 0.2* | |||

| 12-month attempts (general population): 0.4 | |||

| Renberg, 2001 (221) | Northern Sweden, general population | 521 adults (18–65 years) from 1986; 636 adults (18–65 years) from 1996 | Lifetime ideation (1986): 33.3 |

| Lifetime ideation (1996): 21.1 | |||

| Lifetime plans (1986): 10.4 | |||

| Lifetime plans (1996): 13.1 | |||

| Lifetime attempts (1986): 2.6 | |||

| Lifetime attempts (1996): 2.7 | |||

| 12-month ideation (1986): 12.5 | |||

| 12-month ideation (1996): 8.6 | |||

| 12-month plans (1986): 4.2 | |||

| 12-month plans (1996): 4.1 | |||

| 12-month attempts (1986): 0.6 | |||

| 12-month attempts (1996): 0.2 | |||

| Rancans et al., 2003 (222) | Latvia, general population | 667 adults (≥18 years) | Lifetime ideation: 33.0 |

| Lifetime plans: 19.5 | |||

| Lifetime attempts: 5.1 | |||

| 12-month ideation: 21.3 | |||

| 12-month plans: 12.2 | |||

| 12-month attempts: 1.8 | |||

| Crawford et al., 2005 (223) | England | 4,171 adults (16–74 years) among representative samples of White, Irish, Black Caribbean, Bangladeshi, Indian, and Pakistani ethnic groups | Lifetime ideation: 10 |

| Lifetime attempts: 3 | |||

| De Leo et al., 2005 (224) | Queensland, Australia, nationally representative sample | 11,572 adults (≥18 years) | Lifetime ideation: 10.4 |

| Lifetime plans: 4.4 | |||

| Lifetime attempts: 4.2 | |||

| 12-month attempts: 0.4 | |||

| Mohammadi et al., 2005 (225) | Iran, general population | 25,180 adults (26–55 years) | Lifetime attempts: 1.4 |

| Agoub et al., 2006 (226) | Casablanca, Morocco, sample representative of urban general population | 800 adults (≥15 years) | Lifetime attempts: 2.1 |

| 1-month plans: 1.0* | |||

| 1-month attempts: 0.8* | |||

| Beautrais et al., 2006 (227) | New Zealand, nationally representative sample | 12,992 adults (≥16 years) | Lifetime ideation: 15.7 |

| Lifetime plans: 5.5 | |||

| Lifetime attempts: 4.5 | |||

| 12-month ideation: 3.2 | |||

| 12-month plans: 1.0 | |||

| 12-month attempts: 0.4 | |||

| Liu et al., 2006 (228) | Hong Kong, territory-specific representation | 2,015 adults (20–59 years) | Lifetime ideation: 28.1 |

| 12-month ideation: 6.0 | |||

| 12-month plans: 1.9 | |||

| 12-month attempts: 1.4 | |||

| Ovuga et al., 2006 (229) | Makerere University, Uganda | 101 older students (23.5 years (SD†, 5.0)) and 253 younger students (21.3 years (SD, 2.4)) | Lifetime ideation (older students): 8.9 |

| Lifetime ideation (younger students): 56.0 | |||

| Tran Thi Thanh et al., 2006 (230) | Dongda district, Hanoi, Vietnam, general population | 2,260 adults (≥14 years) | Lifetime ideation: 8.9 |

| Lifetime plans: 1.1 | |||

| Lifetime attempts: 0.4 | |||

| 12-month ideation: 3.3 | |||

| 12-month plans: 0.5 | |||

| 12-month attempts: 0.1 | |||

| Bernal et al., 2007 (231) | Six European countries (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, and Spain), all nationally representative samples | 8,796 adults (≥18 years) | Lifetime ideation: 7.8 |

| Lifetime attempts: 1.3 | |||

| Bromet et al., 2007 (232) | Ukraine, nationally representative samples | 4,719 adults (≥18 years) | Lifetime ideation: 8.2 |

| Lifetime plans: 2.7 | |||

| Lifetime attempts: 1.8 | |||

| 12-month ideation: 1.8 | |||

| Gureje et al., 2007 (233) | 21 out of 36 states of Nigeria | 6,752 adults (≥18 years) | Lifetime ideation: 3.2 |

| Lifetime plans: 1.0 | |||

| Lifetime attempts: 0.7 | |||

| Lee et al., 2007 (234) | Beijing and Shanghai, China, general population | 5,201 adults (≥18 years) | Lifetime ideation: 3.1 |

| Lifetime plans: 0.9 | |||

| Lifetime attempts: 1.0 | |||

| Nojomi et al., 2007 (235) | Karaj City, Tehran Province, Iran | 2,300 adults (including as early as 15 years), attempt rate from pilot study | Lifetime attempts: 1.2 |

| Borges et al., 2008 (236) | Mexico, nationally representative sample | 5,782 adults | Lifetime ideation: 8.1 |

| Lifetime plans: 3.2 | |||

| Lifetime attempts: 2.7 | |||

| Hintikka et al., 1998 (237) | Finland, general population | 4,868 adults | 12-month ideation (females): 2.4 |

| 12-month ideation (males): 2.3 | |||

| Scocco and De Leo, 2002 (43) | Padua, Italy, community-dwelling elderly population | 611 older adults (≥65 years) | 12-month ideation: 9.5 |

| 12-month attempts: 3.8 | |||

| Gunnell et al., 2004 (238) | United Kingdom, nationally representative sample | 2,404 adults (16–74 years) | 12-month ideation: 2.3 |

| Fairweather et al., 2007 (239) | Australia | 7,485 adults (cohorts of 20–24, 40–44, and 60–64 years) | 12-month ideation: 8.2 |

| De Leo et al., 2001 (60) | Sweden, France, United Kingdom, Denmark, Italy, Norway, Finland, the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Spain, and Hungary | 1,518 older persons (≥65 years) | Monitoring period of 3–5 years, at least one attempt: 0.06* |

| International studies—adolescents (n = 20) | |||

| Olsson and von Knorring, 1999 (240) | Sweden (one town) | 2,300 adolescents (16–17 years) | Lifetime attempts: 2.4 |

| Elklit, 2002 (241) | Denmark, nationally representative sample | 390 eighth-graders (mean age = 14.5 years) | Lifetime attempts: 6.2 |

| Blum et al., 2003 (152) | Antigua, Bahamas, Barbados, British Virgin Islands, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, and St. Lucia | 15,695 adolescents (10–18 years) | Lifetime attempts: 12.1 |

| Gmitrowicz et al., 2003 (242) | Lodz, Poland, community population | 1,663 adolescents (14–21 years) | Lifetime ideation: 30.8 |

| Lifetime attempts: 7.9 | |||

| Toros et al., 2004 (243) | Turkey | 4,143 children and adolescents (10–20 years) | Lifetime attempts: 1.9 |

| Zemaitiene and Zaborskis, 2005 (244) | Lithuania, nationally representative sample | 15,586 children (11, 13, and 15 years) | Lifetime plans: 3.0 |

| Lifetime attempts: 1.5 | |||

| Young et al., 2006 (245) | Central Clydeside Conurbation, Scotland, community population | 1,258 older adolescents (19 years) | Lifetime attempts: 6.4 |

| Sidhartha and Jena, 2006 (246) | New Delhi, India, student population | 1,205 adolescents (12–19 years) | Lifetime ideation: 21.7 |

| Lifetime attempts: 8.0 | |||

| 12-month ideation: 11.7 | |||

| 12-month attempts: 3.5 | |||

| Dervic et al., 2007 (247) | Vienna, Austria, student population | 214 adolescents (15.6 years (SD, 1.4)) | Lifetime ideation: 37.9 |

| Silviken and Kvernmo, 2007 (248) | Arctic Norway, representative samples of different ethnic groups | 591 indigenous Sami adolescents and 2,100 majority adolescents (16–18 years) | Lifetime attempts: 9.5 |

| 6-month ideation: 15.1* | |||

| Rey Gex et al., 1998 (249) | Switzerland, nationally representative sample | 9,268 adolescents (15–20 years) | 12-month ideation: 26 |

| 12-month plans: 15 | |||

| 12-month attempts: 3 | |||

| Tousignant et al., 1999 (250) | Canadian sample of refugees from 35 countries | 203 adolescents (13–19 years) | 12-month attempts: 3.4 |

| Miauton et al., 2003 (251) | Switzerland, nationally representative sample | 9,268 adolescents (15–19 years) | 12-month attempts: 3.0 |

| Yip et al., 2004 (252) | Hong Kong, territory-specific representation | 2,586 adolescents (13–21 years) | 12-month ideation: 17.8 |

| 12-month plans: 5.4 | |||

| 12-month attempts: 8.4 | |||

| Rodriguez et al., 2006 (253) | Nicaragua, general population | 278 adolescents (15–24 years) | 12-month ideation: 19.8 |

| 12-month plans: 5.0 | |||

| 12-month attempts: 1.8 | |||

| Rudatsikira et al., 2007 (254) | Guyana, student population | 1,197 adolescents (<14–≥16 years) | 12-month ideation: 18.4 |

| Kaltiala-Heino et al., 1999 (255) | Two regions of Finland, student population | 16,410 adolescents (14–16 years) | Current ideation: 2.2* |

| Khokher et al., 2005 (256) | Karachi, Pakistan, medical student population | 217 medical students (19–22 years) | Recent ideation: 31.3* |

| Liu et al., 2005 (257) | Shandong, China (five high schools) | 1,362 adolescents (12–18 years) | 6-month ideation: 19.3* |

| 6-month attempts: 7.0* | |||

| Ponizovsky et al., 1999 (258) | Israel, immigrant population | 406 Russian-born Jewish immigrants to Israel (11–18 years); 203 indigenous Jewish adolescents in Russia; 104 Indigenous Jewish adolescents in Israel | 6-month ideation (immigrants): 10.9* |

| 6-month ideation (Russian natives): 3.5* | |||

| 6-month ideation (Israeli natives): 8.7* | |||

| Cross-national studies (n = 3) | |||

| Weissman et al., 1999 (26) | Nine countries, varying designs and surveys | Approximately 40,000 adults | Lifetime ideation (range): 2.1–18.5 |

| Lifetime attempts (range): 0.7–5.9 | |||

| Bertolote et al., 2005 (27) | 10 countries, same community-based survey in 10 hospital catchment areas | 69,797 children, adolescents, and adults (≥5 years) | Lifetime ideation (range): 2.6–25.4 |

| Lifetime plans (range): 1.1–15.6 | |||

| Lifetime attempts (range): 0.4–4.2 | |||

| Nock et al., 2008 (25) | 17 countries, same household survey; most samples were nationally representative | 84,850 adults | Lifetime ideation (range): 3.0–15.9 |

| Lifetime plans (range): 0.7–5.6 | |||

| Lifetime attempts (range): 0.5–5.0 | |||

| Lifetime ideation (pooled): 9.2 | |||

| Lifetime plans (pooled): 3.1 | |||

| Lifetime attempts (pooled): 2.7 | |||

Not included in prevalence estimates in text because of differences in measurement.

SD, standard deviation.

Studies in adolescents (ages 12–17 years) suggest that lifetime prevalences are in the range of 19.8–24.0 percent (IQR, 19.8–24.0) for suicide ideation and 3.1–8.8 percent (IQR, 3.1–8.8) for suicide attempts (there are no lifetime data on suicide plans). Twelve-month prevalence estimates are in the range of 15.0–29.0 percent (IQR, 16.9–24.1) for suicide ideation, 12.6–19.0 percent (IQR, 13.8–18.2) for suicide plans, and 7.3–10.6 percent (IQR, 8.0–8.8) for suicide attempts (table 1).

A comparison of the prevalence estimates for suicidal behavior between adults and adolescents raises the question of how it is possible that adults have a lower lifetime prevalence than adolescents. In fact, the lifetime prevalence of each individual suicidal behavior among adults is lower than the 12-month prevalence among adolescents. One possible explanation is that the rates of suicidal behavior in the United States are increasing dramatically among adolescents, but this is inconsistent with data on trends in adolescent suicide (reviewed above) and suicidal behaviors (reviewed below). A more likely explanation is that adults underreport lifetime suicidal behaviors. Evidence of such a bias was found in a study by Goldney et al. (44), in which 40 percent of adolescents who initially reported suicide ideation at one time point denied any lifetime history of suicide ideation when interviewed 4 years later as young adults.

Recent trends

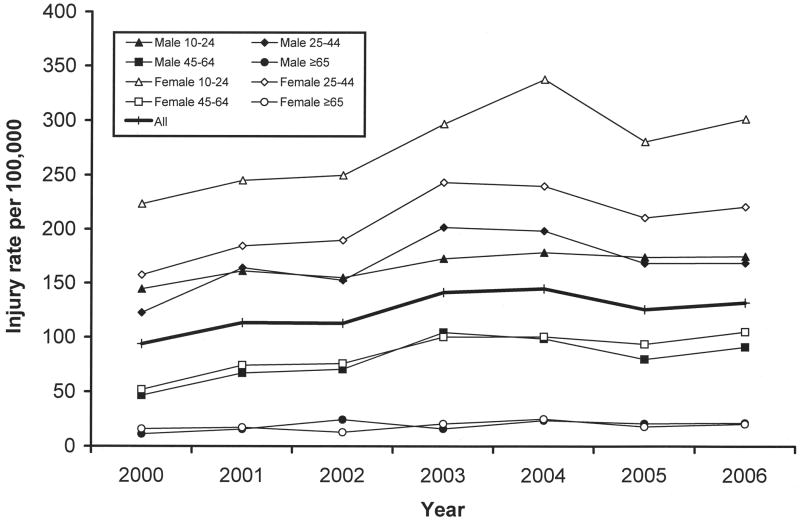

CDC data (37) from 2001–2006 are available for comparison. As figure 5 shows, the rate of nonfatal self-injury (both suicidal and nonsuicidal in nature) increased during this period. Each age and sex group examined showed an increase, and the overall rate increased from 113.4 per 100,000 to 132.0 per 100,000 (16.5 percent). Data from our systematic review suggested that the estimated 12-month prevalence of suicidal behaviors among adults in the United States has remained stable in recent years. One recent study revealed that although use of health-care services increased dramatically among suicidal adults in the decade between 1990–1992 and 2001–2003, the 12-month prevalence did not change significantly for suicide ideation (2.8 percent→3.3 percent), suicide plans (0.7 percent→1.0 percent), or suicide attempts (0.4 percent→0.6 percent) (22). Data on the 12-month prevalence of suicidal behaviors among adolescents from the CDC Youth Risk Behavior Survey are more encouraging and indicate that from 1991 to 2005 there was a decrease in the rates of suicide ideation (29.0 percent→16.9 percent) and plans (18.6 percent→13.0 percent) but no such decrease for attempts (7.3 percent→8.4 percent) (45).

FIGURE 5.

Rates of nonfatal self-injury in the United States, by age group, and year, 2001–2006. Data were obtained from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) (37).

Onset and course

The earliest onset ever reported for suicidal behaviors is in children as young as 4–5 years (21, 46–50). However, some authors have argued that children younger than 10 years are rarely capable of understanding the finality of death and therefore cannot make a suicide attempt (51, 52). The most consistently reported pattern is that the risk of first onset for suicidal behavior increases significantly at the start of adolescence (12 years), peaks at age 16 years, and remains elevated into the early 20s. This means that adolescence and early adulthood are the times of greatest risk for first onset of suicidal behavior (47, 53). Early stressors such as parental absence and family history of suicidal behavior have been associated with an earlier age of onset (53, 54).

Relatively few investigators have examined the course of suicidal behaviors. Data using retrospective recall of age of onset suggest that 34 percent of lifetime suicide ideators go on to make a suicide plan, that 72 percent of persons with a suicide plan go on to make a suicide attempt, and that 26 percent of ideators without a plan make an unplanned attempt (47). The majority of these transitions occur within the first year after onset of suicide ideation (60 percent for planned first attempts and 90 percent for unplanned first attempts) (47). These findings indicate that the presence of suicide ideation and a suicide plan significantly increase the risk of a suicide attempt and that risk of a suicide attempt among persons without a plan is limited primarily to the first year after onset of suicide ideation. Prior suicidal behaviors are among the strongest predictors of subsequent suicidal behaviors (4, 55–57); however, suicide ideation in the continued absence of a plan or attempt is associated with decreasing risk of suicide plans and attempts over time (58).

Suicidal behavior cross-nationally

Current rates

As with suicide death, there is considerable cross-national variability in the prevalence of suicidal behaviors. Across all studies identified that assessed lifetime prevalence among adults in individual countries, estimates varied widely for suicide ideation (3.1–56.0 percent; IQR, 8.0–24.9), suicide plans (0.9–19.5 percent; IQR, 1.5–9.4), and suicide attempts (0.4–5.1 percent; IQR, 1.3–3.5). Estimates of the 12-month prevalence of suicidal behaviors among adults also showed wide variability for suicide ideation (1.8–21.3 percent; IQR, 2.4–8.8), plans (0.5–12.2 percent; IQR, 0.9–6.2), and attempts (0.1–3.8 percent; IQR, 0.4–1.5). As in the United States, prevalence estimates were consistently higher among adolescents for the lifetime prevalence of suicide ideation (21.7–37.9 percent; IQR, 21.7–37.9), plans (3.0 percent; one study), and attempts (1.5–12.1 percent; IQR, 2.2–8.8), as well as for the 12-month prevalence of suicide ideation (11.7–26.0 percent; IQR, 14.8–22.9), plans (5.0–15.0 percent; IQR, 5.0–15.0), and attempts (1.8–8.4 percent; IQR, 2.7–4.7) (table 1).

One important limitation in comparing results across studies of suicidal behavior is that different studies use different questions to assess these behaviors, so it is not clear how much of the variability observed across studies is due to differences in measurement methods. In three recent cross-national studies, investigators have attempted to remedy this problem by using consistent measurement strategies across countries. These are: 1) the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on Parasuicide (n = 22,665) (28, 59, 60), which included persons engaging in “parasuicide” (i.e., combining suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injury) who were treated at medical centers in 15 European countries; 2) the WHO Multisite Intervention Study on Suicidal Behaviours (n = 69,797) (27, 61, 62), which included community samples in eight countries; and 3) the WHO World Mental Health Survey, which provides data on the epidemiology of suicidal behaviors in 28 countries in the Americas, Europe, Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and the Pacific. Interestingly, all three studies revealed wide cross-national variation in suicidal behaviors. For instance, analyses for the first 17 World Mental Health Survey countries (n = 84,850) yielded prevalence estimates for suicide ideation (3.0–15.9 percent; IQR, 4.4–11.7), plans (0.7–5.6 percent; IQR, 1.6–4.0), and attempts (0.5–5.0 percent; IQR, 1.5–3.2) that were consistent with those reviewed above. The pooled cross-national prevalence estimates in this study were: for suicide ideation, 9.2 percent (standard error, 0.1); for suicide plans, 3.1 percent (standard error, 0.1); and for suicide attempts, 2.7 percent (standard error, 0.1) (25) (table 1). Interestingly, rates of suicidal behavior do not mirror the geographic pattern reported for suicide death (e.g., high rates in Eastern Europe, low rates in South America), nor do they differ systematically between developed and developing countries (25).

Recent trends

Our search did not yield any cross-national studies of trends in suicidal behavior. However, it is notable that the prevalence estimates found in the studies we reviewed are quite consistent with those obtained in an earlier cross-national review of nine studies of adult suicidal behavior conducted in the 1980s (26)—suggesting, but by no means confirming, that there has been no major change in trends over time. Trends in suicidal behavior within individual countries also appear to have been fairly steady over time (22, 58, 63, 64). The fact that within-country trends show internal consistency (i.e., greater agreement on prevalence estimates and evidence of stable patterns over time) means that there must be some stable between-country differences in the determinants of suicidal behavior prevalences and trends that remain to be discovered.

Onset and course

Data on the onset and course of suicidal behaviors appear to be quite consistent cross-nationally and look similar to the previously mentioned data from studies in the United States. Data from the World Mental Health Survey indicate that for all countries examined, the risk of first onset of suicide ideation increases sharply during adolescence and young adulthood and then stabilizes in early midlife (25). There is consistency in the timing and probability of transitioning from suicide ideation to suicide plans and attempts, with 33.6 percent of ideators going on to make a suicide plan (IQR, 29.8–35.6) and 29.0 percent of ideators making an attempt (IQR, 21.2–33.1) (25). In addition, the high risk of transitioning from ideation to a plan and an attempt during the first year after ideation onset that was found in the United States (47) was replicated across all countries examined, with the transition from ideation to an attempt occurring during the first year more than 60 percent of the time across all countries (25). These findings indicate that the onset and course of suicidal behaviors are quite consistent cross-nationally.

Risk factors

Below, we review evidence on risk factors for both suicide and suicidal behaviors, given the substantial overlap in the risk factors reported to predict these behaviors (34, 65), although we note that several studies have reported differences in some risk factors for suicide and suicidal behaviors (66, 67). Most of the studies reviewed above also contained information about risk factors for suicidal behaviors. We do not distinguish between studies conducted in different countries, given that the risk factors reported have been consistent across virtually all countries examined. Given that there is a large and ever-expanding body of literature on risk factors for suicidal behaviors, we provide a summary of only the strongest and most consistently reported factors.

Demographic factors

Demographic risk factors for suicide include male sex, being non-Hispanic White or Native American (in the United States), and being an adolescent or older adult. Demographic risk factors for suicidal behaviors (in the United States and cross-nationally) include being female, being younger, being unmarried, having lower educational attainment, and being unemployed (25–28, 40, 68). The differences in male:female ratio are often attributed to the use of more lethal suicide attempt methods, greater aggressiveness, and higher intent to die among men (34, 69). As mentioned above in connection with India and China, the gender-specific lethality of methods may vary cross-nationally. The other demographic factors mentioned (younger age, lack of education, and unemployment) may represent increased risk for suicidal behaviors associated with social disadvantage, although the mechanisms through which these factors may lead to suicidal behavior are not yet understood.

Psychiatric factors

The presence of a psychiatric disorder is among the most consistently reported risk factors for suicidal behavior (25, 47, 70–74). Psychological autopsy studies reveal that 90–95 percent of the people who die by suicide had a diagnosable psychiatric disorder at the time of the suicide (75), although this percentage is lower in non-Western countries such as China (76, 77). Mood, impulse-control, alcohol/substance use, psychotic, and personality disorders convey the highest risks for suicide and suicidal behavior (25, 34, 47, 70, 71, 78–81), and the presence of multiple disorders is associated with especially elevated risk (25, 47, 80, 82).

Psychological factors

Researchers have begun to examine more specific constructs that may explain exactly why psychiatric disorders are associated with suicidal behavior. Several such risk factors include the presence of hopelessness (83–85), anhedonia (49, 86), impulsiveness (70, 87–89), and high emotional reactivity (86, 87, 90), each of which may increase psychological distress to a point that is unbearable and lead a person to seek escape via suicide (88, 91–93).

Biologic factors

Family, twin, and adoption studies provide evidence for a heritable risk of suicide and suicidal behavior (94–99). Much of the family history of suicidal behavior may be explained by the risk associated with mental disorders (100); however, some studies have provided evidence for familial transmission of suicidal behavior even after controlling for mood and psychotic disorders (101). Researchers have not identified genetic loci for suicide in molecular genetic studies in light of the complex nature of the phenotype (102, 103) but instead have searched for biologic correlates of suicidal behavior that may arise through gene-environment interactions (104–109). The biologic factors most consistently correlated with suicidal behavior involve disruptions in the functioning of the inhibitory neurotransmitter serotonin. Persons who die by suicide have lower levels of serotonin metabolites in their cerebrospinal fluid (110–113), higher serotonin receptor binding in platelets (114, 115), and fewer presynaptic serotonin transporter sites and greater postsynaptic serotonin receptors in specific brain areas such as the prefrontal cortex (101, 116), suggesting deficits in the ability to inhibit impulsive behavior (101, 117). Notably, however, similar deficits in serotonergic functioning are found in other impulsive/aggressive behaviors such as violence and fire-setting (118) and appear to be nonspecific to suicide.

Stressful life events

Most theoretical models of suicidal behavior propose a diathesis-stress model in which the psychiatric, psychological, and biologic factors above predispose a person to suicidal behavior, while stressful life events interact with such factors to increase risk. Consistent with such a model, suicidal behaviors often are preceded by stressful events, including family and romantic conflicts and the presence of legal/disciplinary problems (72, 76, 119, 120). The experience of persistent stress also may explain why persons in some occupations, such as physicians (121), military personnel (122–125), and police officers (126), may have higher rates of suicidal behavior; however, this increased risk may be explained by the demographic and personality characteristics of people who select such occupations (125, 127). More distal stressors, such as perinatal conditions and child maltreatment, also have been linked to subsequent suicidal behavior (128–132). One goal for future research is to begin to specify the mechanisms through which such factors may increase risk.

Other factors

The list of risk factors outlined above is not exhaustive, and there is emerging evidence for a range of other factors, including access to lethal means such as firearms and high doses of medication (66, 127, 133–135), chronic or terminal illness (136, 137), homosexuality (138–140), the presence of suicidal behavior among one's peers (141–144), and time of year (with higher rates consistently being reported in May and June) (145–148). Improvement in the ability to predict suicidal behavior through the continued identification of specific risk factors represents one of the most important directions for future studies in this area.

Protective factors

Protective factors are those that decrease the probability of an outcome in the presence of elevated risk. Although formal tests of protective factors are rare in the suicide research literature, several studies of factors associated with lower risk of suicidal behavior have yielded interesting results. Religious beliefs, religious practice, and spirituality have been associated with a decreased probability of suicide attempts (149–152). Potential mediators of this relation, such as moral objections to suicide (153) and social support (154), also seem to protect against suicide attempts among persons at risk. Perceptions of social and family support and connectedness also have been studied outside the context of religious affiliation and have been shown to be significantly associated with lower rates of suicidal behavior (155–159). Being pregnant and having young children in the home also are protective against suicide (160, 161); however, the presence of young children is associated with a significantly increased risk of first onset of suicidal ideation. These findings highlight the importance of attending carefully to the dependent variable in question when examining risk and protective factors for suicidal behavior.

Prevention/intervention programs

The relatively stable rates of suicide and suicidal behavior over time highlight the need for greater attention to prevention and intervention efforts. A recent systematic review of suicide prevention programs revealed that restricting access to lethal means and training physicians to recognize and treat depression and suicidal behavior have shown impressive effects in reducing suicide rates (135). Means-restriction programs can decrease suicide rates by 1.5–23 percent (162–166), while primary-care physician education and training programs show reductions of 22–73 percent (167–170). Although effective prevention programs exist, the fact that many people engaging in suicidal behavior do not receive treatment of any kind (22, 171–173) underscores the need for greater dissemination of information and further development of prevention efforts (41, 174, 175).

Discussion

Summary of findings

The past decade of research on the epidemiology of suicide has yielded several key findings. First, global estimates suggest that suicide continues to be a leading cause of death and disease burden and that the number of suicide deaths will increase substantially over the next several decades. Second, the significant cross-national variability reported in rates of suicide and suicidal behavior appears to reflect the true nature of this behavior and is not due to variation in research methods. Third, there is cross-national consistency in the early age of onset of suicide ideation, the rapid transition from suicidal thoughts to suicidal behavior, and the importance of several key risk factors. Fourth, despite significant developments in treatment research and increased use of health-care services among suicidal persons in the United States, there appears to have been little change in the rates of suicide or suicidal behavior over the past decade.

The 11.1 percent decrease in the US suicide rate since 1990 is encouraging. Enthusiasm is tempered, however, by knowledge of the fact that the suicide rate is currently at approximately the same level as in 1950 and even 1900, with periodic fluctuation between 10.0 per 100,000 and 19.0 per 100,000 over the past 100 years (4, 9, 176). Similar stable patterns have been observed in other countries (177). Moreover, data on nonfatal self-injury show a 16.5 percent increase in such behavior in only the past 6 years, especially for youth. It is possible that the decrease in youth suicide over this period coupled with the increase in nonfatal self-injury treated in emergency departments is the result of decreased lethality of youth suicidal behavior (perhaps due to safer medication and less access to firearms). An alternative possibility is that the increase in nonfatal self-injury is explained largely by increases in the occurrence of nonsuicidal self-injury. More careful assessment of the intent behind self-injury is needed to address this question. Regardless of the ultimate answers to these questions, it is clear that major advances are needed to enhance understanding of the causes of suicidal behavior and to further decrease the loss of life due to suicide.

Research directions

The next generation of epidemiologic studies in this area must move beyond reporting of prevalence estimates and known risk factors. Below we review several developing lines of investigation that could be used to improve research on the epidemiology of suicidal behavior. In doing so, we propose an agenda for future studies in this area that addresses many existing gaps in our understanding of suicidal behavior.

Testing theoretical models

There is no debate among epidemiologists and clinical investigators that suicidal behaviors are complex, multiply determined phenomena, yet most investigators continue to test bivariate associations between atheoretical demographic or psychiatric factors and suicidal behaviors, with little regard for existing theoretical models. Several notable exceptions exist, such as the testing of diathesis-stress models (70) and gene-environment interactions (106). True advances in understanding of suicidal behaviors are likely to come only through increased testing of these and other models.

A related issue is that while most studies examining suicide ideation, plans, and attempts have shown that similar risk factors predict these outcomes, virtually no studies have more specifically tested which factors predict transitions from ideation to plans and attempts. Such an approach has been useful in other areas, such as the study of drug and alcohol problems—where, for instance, factors that predict ever drinking differ from those that predict development of a drinking problem among drinkers, which in turn differ from those that predict alcohol dependence among problem drinkers (178–180). In the suicide literature, interventions that reduce rates of suicide attempts often do not show similar reductions in ideation (181, 182), suggesting that their effect may lie in decreasing the probability of transitioning from ideation to an attempt rather than in reducing ideation altogether. Understanding this kind of specificity can help us strengthen theories about causal processes and develop more effective interventions.

Incorporating methodological advances

Key methodological obstacles in the study of suicidal behavior include the low base rate of suicidal behavior and the motivation to conceal suicidal thoughts and intentions. These problems have hindered suicide research for decades; however, recent methodological advances now offer novel solutions, outlined below.

Low base-rate problem

New developments in survey methodology make it easier than ever before to conduct large surveys using inexpensive methods such as interactive voice-response telephone surveys (183–185) and Web-based surveys (186–188). These methods are most effective when respondents have a known relationship to the researchers, as in the case of clinical samples. Although clinical epidemiology is an underdeveloped research area, advances in the use of electronic medical records and electronic clinical decision support tools will almost certainly lead to an expansion of this field. Prospective research on risk and protective factors for suicide and suicidal behavior could be dramatically improved by such developments.

One important direction is using such methods to study high-risk samples prospectively. For instance, given that nearly 20 percent of high-school students report 12-month suicide ideation and that suicide is the second-leading cause of death among college students in the United States, researchers could screen large samples of college students before their first semester, identify those with recent suicide ideation, and follow that group over time in order to identify risk factors for suicide attempts in this high-risk group. The structure of the college setting (e.g., the availability of the Internet and e-mail, the 4-year time line) greatly increases the feasibility of such studies. On a larger scale, given that approximately 3 percent of US adults report 12-month suicide ideation, resources like the CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (189), which interviews over 350,000 people per year, could identify 10,500 suicide ideators who could be followed prospectively to examine risk factors for a suicide attempt. Psychological autopsy studies could be done with a matched control group of nonattempting ideators; this would yield valuable information about more specific risk factors for suicide. These are only a few of the many directions now possible, given these exciting technologic advances.

Detection of suicidal behavior

Researchers studying sensitive and potentially shameful topics such as illicit drug use, sexual practices, and suicidal behavior have long realized that people often underreport such behavior in order to avoid embarrassment or intervention (190). Methods for limiting the influence of social desirability include using computer-based interviews (191), presenting survey items in written form rather than reading them aloud (192), and using anonymous surveys, which have been shown to yield rates of suicidal behavior as much as 2–3 times higher than those of nonanonymous surveys (193, 194). Another important advance is the development of behavioral methods for assessing implicit thoughts about self-injurious behavior. Methods have recently been developed that use a person's response times to self-injury-related stimuli presented in a brief computer-based test to measure implicit associations with self-injury. Such tests circumvent the use of self-reporting and have been shown to accurately detect and predict suicidal behavior (195, 196). Such methods could be used to supplement self-reports and to test the percentage of cases identified via behavioral methods that also are detected by standard self-report methods to gain a better understanding of the current extent of underreporting of suicidal behavior.

Conducting epidemiologic experiments

Perhaps one of the most important directions for research on the epidemiology of suicidal behavior is increased use of epidemiologic experiments on prevention and intervention procedures. Such studies serve multiple purposes. First, they allow for tests of causation that are not possible with the correlational designs that dominate this area of research. Second, they address the biggest shortcoming in suicide research to date: the inability to dramatically decrease rates of suicidal behavior and mortality despite decades of research and associated commitment of resources.

As a preliminary step, descriptive data are needed on rates of treatment utilization among persons exhibiting suicidal behavior, including data on treatment adequacy and the presence of potentially modifiable barriers to treatment (197, 198). Following this, efforts will be required to build on findings from recent natural experiments, quasi-experiments, and true experiments on methods of suicide prevention (135).

Natural experiments

Changes in social policy or historical events provide valuable opportunities to study factors that may influence suicidal behavior. For instance, one of the biggest controversies in the study and treatment of suicidal behavior is whether the recent development of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) has led to a decrease, or a paradoxical increase, in suicidal behavior among children and adolescents. Epidemiologists are perfectly poised to test this question, especially given advances in the development and maintenance of electronic health records. Several studies have documented a decrease in suicide following the development of SSRIs and associated with the prescription of SSRIs (199–202). However, there has recently been a decrease in the prescription of SSRIs to US children and adolescents following an observed increase in suicide among adolescents taking SSRIs and the issuance of a “black box” warning (a label on the medication package insert indicating possible adverse effects) by the Food and Drug Administration (203, 204). Epidemiologic studies are under way to test differences in suicide trends before and after implementation of the black box warning as mediated by disaggregated changes in levels of SSRIs prescribed to youth.

Quasi-experiments

Quasi-experimental designs strengthen the case for causality and are a useful alternative when true experiments are not feasible, as is often the case in epidemiologic research. One recent example from the suicide literature is the test of the US Air Force Suicide Prevention Program, which was shown to reduce the rate of suicide death by 33 percent within this population (205). Many services currently provided to the public for the purposes of suicide prevention (e.g., suicide hotlines, inpatient hospitalization) have not been adequately tested. Epidemiologic quasi-experimental studies could begin to address services provided in such settings.

True experiments

Some of the most effective suicide prevention programs to date are simple, efficient, and cost-effective but have not been widely tested or disseminated. For instance, one intervention involved simply sending supportive letters four times per year to randomly selected patients following hospital discharge; this significantly decreased the rate of suicide death among such patients (206). Moving forward, many such conceptual and methodological changes are needed in order to decrease the significant levels of death and disability caused by these dangerous behaviors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant (R01MH077883) from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Abbreviations

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- IQR

interquartile range

- SSRIs

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

- WHO

World Health Organization

- WISQARS

Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Prevention of suicide: guidelines for the formulation and implementation of national strategies. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Public Health Service. The Surgeon General's call to action to prevent suicide. Washington, DC: US Public Health Service; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services. With understanding and improving health and objectives for improving health. 2nd. Vol. 2. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. Healthy People 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldsmith SK, Pellmar TC, Kleinman AM, et al., editors. Reducing suicide: a national imperative. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathers CD, Bernard C, Iburg KM, et al. Global Programme on Evidence for Health Policy discussion paper no 54. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003. Global burden of disease in 2002: data sources, methods and results. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murray CL, Lopez AD, editors. The global burden of disease: a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. Electronic article. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Suicide prevention (SUPRE) Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007. http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/suicideprevent/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monk M. Epidemiology of suicide. Epidemiol Rev. 1987;9:51–69. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moscicki EK. Epidemiology of suicide. In: Jacobs DG, editor. The Harvard Medical School guide to suicide assessment and intervention. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, Inc; 1999. pp. 40–51. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borges G, Anthony JC, Garrison CZ. Methodological issues relevant to epidemiologic investigations of suicidal behaviors of adolescents. Epidemiol Rev. 1995;17:228–39. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cantor CH. Suicide in the Western world. In: Hawton K, van Heeringen K, editors. International handbook of suicide and attempted suicide. 1st. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cantor CH, Leenaars AA, Lester D, et al. Suicide trends in eight predominantly English-speaking countries 1960–1989. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1996;31:364–73. doi: 10.1007/BF00783426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng AT, Lee C. Suicide in Asia and the Far East. In: Hawton K, van Heeringen K, editors. International handbook of suicide and attempted suicide. 1st. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levi F, La Vecchia C, Lucchini F, et al. Trends in mortality from suicide, 1965–99. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;108:341–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spirito A, Esposito-Smythers C. Attempted and completed suicide in adolescence. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2006;2:237–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weissman MM. The epidemiology of suicide attempts, 1960 to 1971. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1974;30:737–46. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1974.01760120003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wexler L, Weissman MM, Kasl SV. Suicide attempts 1970–75: updating a United States study and comparisons with international trends. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;132:180–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.132.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerkhof AJFM. Attempted suicide: patterns and trends. In: Hawton K, van Heeringen K, editors. International handbook of suicide and attempted suicide. 1st. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. pp. 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kessler RC, McRae JA., Jr Trends in the relationship between sex and attempted suicide. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:98–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bridge JA, Goldstein TR, Brent DA. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:372–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Borges G, et al. Trends in suicide ideation, plans, gestures, and attempts in the United States, 1990–1992 to 2001–2003. JAMA. 2005;293:2487–95. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, et al. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2515–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa043266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horan JM, Mallonee S. Injury surveillance. Epidemiol Rev. 2003;25:24–42. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxg010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans, and attempts in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:98–105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al. Prevalence of suicide ideation and suicide attempts in nine countries. Psychol Med. 1999;29:9–17. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bertolote JM, Fleischmann A, De Leo D, et al. Suicide attempts, plans, and ideation in culturally diverse sites: the WHO SUPRE-MISS community survey. Psychol Med. 2005;35:1457–65. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705005404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Platt S, Bille-Brahe U, Kerkhof A, et al. Parasuicide in Europe: the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on Parasuicide. I. Introduction and preliminary analysis for 1989. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1992;85:97–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1992.tb01451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Carroll PW, Berman AL, Maris RW, et al. Beyond the Tower of Babel: a nomenclature for suicidology. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1996;26:237–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silverman MM, Berman AL, Sanddal ND, et al. Rebuilding the Tower of Babel: a revised nomenclature for the study of suicide and suicidal behaviors. Part 1: background, rationale, and methodology. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2007;37:248–63. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.3.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silverman MM, Berman AL, Sanddal ND, et al. Rebuilding the Tower of Babel: a revised nomenclature for the study of suicide and suicidal behaviors. Part 2: suicide-related ideations, communications, and behaviors. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2007;37:264–77. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.3.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Posner K, Oquendo MA, Gould M, et al. Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment (C-CASA): classification of suicidal events in the FDA's pediatric suicidal risk analysis of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1035–43. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.7.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nock MK, Prinstein MJ. Clinical features and behavioral functions of adolescent self-mutilation. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114:140–6. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nock MK, Kessler RC. Prevalence of and risk factors for suicide attempts versus suicide gestures: analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115:616–23. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nock MK, Joiner TE, Jr, Gordon KH, et al. Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Res. 2006;144:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. WISQARS fatal injuries: mortality reports. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008. http://webapp.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/mortrate.html. [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. WISQARS nonfatal injuries: nonfatal injury reports. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008. http://webapp.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/nfirates.html. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar V. Burnt wives—a study of suicides. Burns. 2003;29:31–5. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(02)00235-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee S, Kleinman A. Suicide as resistance in Chinese society. In: Perry EJ, Selden M, editors. Chinese society: change, conflict and resistance. 2nd. London, United Kingdom: Routledge; 2003. pp. 289–311. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bertolote JM, Fleischmann A. A global perspective in the epidemiology of suicide. Suicidology. 2002;7:6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jenkins R. Addressing suicide as a public health problem. Lancet. 2002;359:813–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07958-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pescosolido BA, Mendelsohn R. Social causation or social construction of suicide? An investigation into the social organization of official rates. Am Sociol Rev. 1986;51:80–101. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scocco P, De Leo D. One-year prevalence of death thoughts, suicide ideation and behaviours in an elderly population. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17:842–6. doi: 10.1002/gps.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goldney RD, Smith S, Winefield AH, et al. Suicidal ideation: its enduring nature and associated morbidity. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1991;83:115–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1991.tb07375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Youth Risk Behavior Survey: 1991–2005: trends in the prevalence of suicide ideation and attempts. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007. http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/pdf/trends/2005_YRBS_Suicide_Attempts.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Conwell Y, Duberstein PR. Suicide in elders. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;932:132–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters EE. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:617–26. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tishler CL, Reiss NS, Rhodes AR. Suicidal behavior in children younger than twelve: a diagnostic challenge for emergency department personnel. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:810–18. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nock MK, Kazdin AE. Examination of affective, cognitive, and behavioral factors and suicide-related outcomes in children and young adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2002;31:48–58. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3101_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pfeffer CR. Diagnosis of childhood and adolescent suicidal behavior: unmet needs for suicide prevention. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:1055–61. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cuddy-Casey M, Orvaschel H. Children's understanding of death in relation to child suicidality and homicidality. Clin Psychol Rev. 1997;17:33–45. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(96)00044-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pfeffer CR. Childhood suicidal behavior. A developmental perspective. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1997;20:551–62. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70329-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bolger N, Downey G, Walker E, et al. The onset of suicidal ideation in childhood and adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 1989;18:175–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02138799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roy A. Family history of suicidal behavior and earlier onset of suicidal behavior. Psychiatry Res. 2004;129:217–19. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goldstein RB, Black DW, Nasrallah A, et al. The prediction of suicide. Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value of a multivariate model applied to suicide among 1906 patients with affective disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:418–22. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810290030004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Joiner TE, Conwell Y, Fitzpatrick KK, et al. Four studies on how past and current suicidality relate even when “everything but the kitchen sink” is covaried. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114:291–303. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Borges G, Angst J, Nock MK, et al. A risk index for 12-month suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Psychol Med. 2006;36:1747–57. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Borges G, Angst J, Nock MK, et al. Risk factors for the incidence and persistence of suicide-related outcomes: a 10-year follow-up study using the National Comorbidity Surveys. J Affect Disord. 2008;105:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Michel K, Ballinari P, Bille-Brahe U, et al. Methods used for parasuicide: results of the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on Parasuicide. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2000;35:156–63. doi: 10.1007/s001270050198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.De Leo D, Padoani W, Scocco P, et al. Attempted and completed suicide in older subjects: results from the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study of Suicidal Behaviour. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:300–10. doi: 10.1002/gps.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bertolote JM, Fleischmann A. Suicidal behavior prevention: WHO perspectives on research. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2005;133:8–12. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fleischmann A, Bertolote JM, De Leo D, et al. Characteristics of attempted suicides seen in emergency-care settings of general hospitals in eight low- and middle-income countries. Psychol Med. 2005;35:1467–74. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705005416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Statham DJ, Heath AC, Madden PA, et al. Suicidal behaviour: an epidemiological and genetic study. Psychol Med. 1998;28:839–55. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gibb S, Beautrais A. Epidemiology of attempted suicide in Canterbury Province, New Zealand (1993–2002) N Z Med J. 2004;117:U1141. Electronic article. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Beautrais AL. Suicide and serious suicide attempts in youth: a multiple-group comparison study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1093–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brent DA, Perper JA, Goldstein CE, et al. Risk factors for adolescent suicide. A comparison of adolescent suicide victims with suicidal inpatients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:581–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800300079011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brent DA, Perper JA, Moritz G, et al. Psychiatric risk factors for adolescent suicide: a case-control study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32:521–9. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199305000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vijayakumar L, John S, Pirkis J, et al. Suicide in developing countries (2): risk factors. Crisis. 2005;26:112–19. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.26.3.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Beautrais AL. Gender issues in youth suicidal behaviour. Emerg Med (Fremantle) 2002;14:35–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2026.2002.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]