Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus isolates collected from sites of intramammary infection during a 10-month period and from extramammary sites (dairy cow teat skin, teat canals, and skin lesions; milking liners; and hands and nostrils of milking personnel) at two separately managed Finnish dairy herd establishments were analyzed to study the sources and reservoirs of bovine S. aureus intramammary infection. Selected isolates were subjected to pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) typing and PCR analysis for genes encoding hemolysins (hla to hlg), leukocidins (lukED and lukM), superantigens (sea, sec, sed, seg to seo, seu, and tst), adhesins (fnbA and fnbB), and penicillin and methicillin resistance (blaZ and mecA). S. aureus was found throughout the herds in 94% of the cows. Nine PFGE types were found, with the herds each having their own predominant type and sharing one type. The degree of diversity of PFGE types in herd II, which integrated foreign heifers, was higher than that in herd I. For both herds, the majority of the PFGE-typed isolates both from milk and from extramammary sites represented the predominant PFGE types. In isolates from herd I, the most prevalent genes were hla-hlg, lukED, and fnbA; in those from herd II, they were hla, hld, hlg, lukED, and fnbA. The other genes were pulsotype linked within the herds. The predominant PFGE types carried both fnbA and fnbB; only fnbA was detected in the other PFGE types. No connection between specific virulence genes and the origins of isolates was found. The results suggest that for the two herds, most S. aureus isolates from extramammary sites were indistinguishable from the isolates infecting the mammary gland and that those sites can thus act as origins and reservoirs of intramammary infections. However, contamination in the opposite direction cannot be excluded.

Staphylococcus aureus is a major cause of contagious bovine mastitis. Depending on the country, prevalence values of 3.4 to 8.2% for quarter infections have been recorded previously in surveys in which samples have been taken from all quarters of all cows in randomly selected herds (30, 32, 43). Most dairy cows are probably exposed to S. aureus, as the organism is a frequent resident of the skin and mucous epithelia of dairy cows and other mammals, including humans, and is commonly found in the barn environment (35). The presence of the bacterium is likely to be of little consequence for the most part, but if the defense mechanisms of the host fail, S. aureus may become pathogenic.

S. aureus can produce more than 30 virulence factors that contribute to establishing and maintaining infection. The factors can be divided into two general groups, including surface-associated factors and degradative enzymes, together with exotoxins. S. aureus microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules comprise surface proteins that promote colonization by being able to bind the host cellular matrix. This group includes fibrinogen-, fibronectin-, and collagen-binding proteins, which function during the initial stages of infection (31). Following successful colonization, S. aureus bacteria are able to secrete a plethora of other factors through which they obtain nutrients, invade, survive, and disseminate. These factors include enzymes and exotoxins, which are responsible for the pathological effects observed during the development of infection. Hemolysins (alpha, beta, delta, and gamma) and leukocidins are able to damage host cells by virtue of their cytolytic effects. In the event of the rapid progression of infection, the production of superantigens (enterotoxins, toxic shock syndrome toxin, and epidermolysins) can stimulate host defenses that can have severe, even lethal, consequences for the host (33).

Staphylococcal virulence factors have been identified for many S. aureus collections isolated in cases of bovine intramammary infection (IMI). In studies in which the production of staphylococcal virulence factors has been detected, most S. aureus isolates originating from bovine mastitis specimens have been shown to produce alpha- and beta-hemolysin and leukocidins or carry the respective genes (1, 34). Some superantigen determinants in particular, like sec and tst, have been common and typical for certain genetic lineages (9, 51). The genes seg to seo, which belong to the enterotoxigenic cluster egc, have been found frequently in S. aureus isolates from bovine mastitis specimens (9, 10, 40). Furthermore, the enterotoxin-encoding genes sed and sej have been detected in association with the penicillin resistance of certain strains (13). Such strains have been overrepresented in cases of persistent S. aureus mastitis (13).

Knowledge about the genetic variability within different S. aureus populations may help in the identification of the most likely source of an isolate. S. aureus has been found to be rather host specific (2, 14). Part of this specificity or host adaptation may be due to the acquisition or loss of mobile accessory genetic elements (7). It is not yet known whether specific virulence factors are associated with bovine mastitis. Genotypes of S. aureus strains residing in extramammary sites in dairy cows or in the barn environment have differed from those of strains isolated from sites of mastitis (50), which suggests that some bovine S. aureus strains may be specialized in infecting the bovine udder. This specialization may imply that strains predominantly causing IMI are more virulent than those present at extramammary sites. If specific virulence determinants could be identified, S. aureus IMI could be controlled by, for example, preventing the expression of these bacterial factors.

The aim of this study was to examine the molecular types and genetic profiles of S. aureus isolates originating from sites of IMI and to compare them with the molecular types and genetic profiles of S. aureus strains isolated from skin lesions and other body sites of dairy cows and from extramammary sites at two herd establishments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Herd and cow data.

S. aureus isolates were collected from two commercial dairy herds (herds I and II) located in southern Finland and having a high incidence of S. aureus mastitis. The herds were selected based on the different management styles. On average, herd I had 30 lactating Holstein-Friesian cows and a mean annual milk production of 9,600 kg. The herd was closed; no animals were purchased from other herds. During the indoor season, the cows were housed in a free-stall barn with a concrete slatted floor and cubicles with peat as a bedding material; the cows grazed during the summer. The cows were milked twice a day in a 2-by-5 herringbone milking parlor. Udder health management included regular monitoring of the cows and milking machines, the maintenance of a milking order, forestripping before milking, the assessment of somatic cell counts in milk from all lactating quarters by the California Mastitis Test (CMT) every second week, the use of individual paper towels for udder cleaning, the use of gloves during milking, and postmilking teat disinfection using an iodine teat dip (0.75% active iodine). Animals with cases of clinical and subclinical mastitis were treated with antimicrobials, and treatment was always based on bacteriological diagnosis and susceptibility testing. Cows with a history of IMI in the preceding lactation received antimicrobial dry-cow therapy.

Herd II was an open herd that included replacement heifers from all over Finland. On average, the herd had 54 Ayrshire cows and a mean annual milk production of 9,185 kg. The cows were housed in a tied-stall barn with concrete floor cubicles containing peat bedding and were milked twice a day. Heifers were kept in a separate building for several months before transfer to the cow house, which usually occurred during early pregnancy. Mastitis control was similar to that for herd I, with the exception that quarters subclinically infected with S. aureus were usually not treated but prematurely dried off, especially if the isolate was penicillin resistant (produced β-lactamase).

Sample collection and microbiological procedures.

Milk samples from all lactating cows with mastitis were collected by the herdsmen using an aseptic technique during a 10-month period from October 2002 to August 2003. The milk samples were submitted to the laboratories of the Finnish Food Safety Authority and Valio Ltd., where bacterial culturing was conducted according to routine methods (15). During the farm visits in March (herd I) and in May (herd II) of 2003, milk samples from all lactating quarters and samples from extramammary sites were collected as listed in Table 1 (this sampling is hereinafter referred to as the farm visit). Milk somatic cell counts were estimated by the CMT using the Nordic classification (18). In this method, scoring from 1 to 5 is used and a score of 3 (300,000 cells/ml of milk) is the threshold for mastitis. In herd II, three preparturient heifers close to parturition were included in the sampling. Milk samples were cultured according to routine methods, and bacterial species were preliminarily identified using conventional procedures described previously (15).

TABLE 1.

Numbers and origins of samples collected from herds I and II during farm visits

| Origin of samples | No. of samples from herd:

|

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | ||

| Milk | 108 | 197 | 305 |

| Teat wall | 108 | 204 | 312 |

| Teat orifice | 108 | 192 | 300 |

| Teat canal | 108 | 191 | 299 |

| Skin lesion | 8 | 33 | 41 |

| Liner before milking | 4 | 32 | 36 |

| Liner after milking | 108 | 186 | 294 |

| Milkers' hands | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Milkers' nostrils | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Total | 556 | 1,041 | 1,597 |

For the milk samples taken by the herdsmen before and after the farm visit, a quarter was considered to be infected with S. aureus when ≥500 CFU of S. aureus/ml was detected in the milk. For the milk samples taken at the farm visit, quarters were considered to have S. aureus IMI when ≥100 CFU of S. aureus/ml was detected in the milk if the CMT score was ≥3. Milk samples containing more than two bacterial species were considered to be contaminated. The IMI was classified as persistent if the same S. aureus pulsotype was repeatedly isolated from the same quarter during the same lactation. New infections were defined as those in quarters regarded as healthy before the farm visit but yielding samples in which S. aureus was detected later during the study period.

Samples from the teat walls (the skin of the teat barrels), the teat ends around the teat orifice, the teat canals, and all clearly visible skin lesions of the cows (mainly abrasions on the hind legs and a few lesions on teat or udder skin) and from the hands and nostrils of the milking personnel were collected by using sterile, singly packaged, cotton-tipped swabs (Technical Service Consultants Ltd., Heywood, United Kingdom). Swabs were moistened with Trypticase soy broth (TSB; Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, United Kingdom) before use. Teat canal samples were taken by rotating ultrafine, sterile, cotton-tipped swabs (Deltalab S. A., Barcelona, Spain) 360° in the canal. The teat was cleaned, disinfected with chlorhexidine solution, and dried with a paper towel before the insertion of the swab into the canal. Samples from the hands and nostrils of the staff were taken by rotating the swabs 360° between the bases of the fingers of both hands or in both nostrils. Four random swabs from liners used for herd I and swabs from all milking liners used for herd II were taken prior to milking to control for the cleanliness of the liners. Milking liners were also sampled after the milking of each cow. The swabs were rotated 360° at the point where the liner joined the short milking tube. Disposable latex gloves were used during the sampling.

After use, all swabs were immediately placed into sterile plastic containers filled with 5 ml of TSB. The containers were cooled and transported to the laboratory within a few hours. The isolation of S. aureus was carried out based on descriptions by Lancette and Tatini (19) with the following modifications. After the samples were kept for 30 min at room temperature, 5 ml of TSB containing 20% NaCl was added and the samples were subjected to a vortex and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Subsequently, 0.1-ml aliquots of the cultures were transferred into duplicate plates of Baird-Parker agars and spread with a plastic triangle. The agars were incubated at 37°C for 24 h and checked and were then incubated another 24 h if no growth was observed. Black, dark gray, or shiny brown colonies with clear zones of hemolysis were selected for Gram staining and catalase and rabbit plasma coagulase tests. Other colonies suspected of being S. aureus, but without a clear zone, were transferred onto acriflavine agar and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Colonies with yellow growth were tested as potential S. aureus colonies as described previously. The isolates were stored at −70°C in Protect bacterial preservers (Technical Service Consultants Ltd., Heywood, United Kingdom).

PFGE typing.

All S. aureus isolates from mastitic milk, skin lesions, and human hands and nostrils were typed using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). At least one randomly selected isolate, if available, from the teat skin and/or the teat canal and/or the milking liner (after milking) per cow was typed to obtain insight into PFGE types in healthy and mastitic cows. Bacterial DNA for PFGE typing was digested with SmaI according to the method of Salmenlinna et al. (37). PFGE was conducted using the procedures of Murchan et al. (26). The relatedness of the fingerprints was assessed by using visual examination according to criteria described by Tenover et al. (44) and by using computer analysis with BioNumerics software (version 4.00; Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium) with Dice coefficients and clustering by the unweighted-pair group method with arithmetic means; position tolerance was set at 1.0, and the cluster cutoff was set at an 80% similarity level. The different PFGE fingerprints (distinguished by seven or more band differences) were assigned different uppercase letters; patterns with one to six band shifts were accordingly represented by designations with numeric suffixes.

DNA isolation and PCR amplifications.

All PFGE-typed S. aureus strains from herd I (n = 102) and 127 PFGE-typed strains from herd II were subjected to PCR. Bacterial DNA was isolated by using the DNeasy tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), with the modification that 11 U of lysostaphin (Sigma) was added at the cell lysis step. The DNA quantity for each isolation was measured using a GeneQuant II RNA/DNA calculator (Pharmacia) and diluted to a concentration of 100 ng/μl with Tris-EDTA buffer. The identification of S. aureus was confirmed according to the method of Brakstad et al. (3) by the amplification of the nuc gene. The β-lactamase gene blaZ was detected by primers designed by Vesterholm-Nielsen et al. (46) under the conditions described earlier by Haveri et al. (12). The genes sea, sec, sed, tst, and mecA were amplified by using primers and PCR conditions described by Mehrotra et al. (23); the primers were grouped into two multiplex sets, set 1 (for sea, sec, and sed) and set 2 (for tst and mecA). Primers for the genes seg-sej, lukED, lukM, hla, hlb, and hld were designed by Jarraud et al. (16), those for sek-seo were designed by Smyth et al. (40), those for seu were designed by Letertre et al. (20), those for hlg were designed by Lina et al. (21) and Jarraud et al. (16), and those for fnbA and fnbB were designed by Nashev et al. (28). One of the hlg-specific primers was modified as outlined by von Eiff et al. (47). Each 50-μl PCR mixture contained 2.5 U of DyNAzyme DNA polymerase (Finnzymes, Espoo, Finland), 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphate mix, 20 pmol of each primer, and 100 ng of DNA template. Multiplex PCRs were furthermore used for the detection of seg, seh, and sei (with set 3 primers); hla and hlb (with set 4 primers); hld and hlg (with set 5 primers); sen and seo (with set 6 primers); and lukED and lukM (with set 7 primers). Individual PCRs were conducted for sej, sek, sel, sem, seu, fnbA, and fnbB. Cycling conditions described by Mehrotra et al. (23) were used for the amplification of seg to sej, lukED, lukM, and hla to hlg. The conditions described by Smyth et al. (40) were used for sek-seo and seu. The conditions for the amplification of fnbA and fnbB included an initial denaturation step (5 min at 94°C), followed by 30 cycles of amplification (denaturation for 30 s at 94°C, annealing for 30 s at 50°C, and elongation for 1 min at 72°C) terminated with a 7-min incubation step at 72°C. The PCRs were carried out in a Peltier 200 thermal cycler (MJ Research, Waltham, MA), and each gene from each isolate was tested at least twice. The amplification products were analyzed by electrophoresis through 1% agarose gels. A positive control and a negative control (a reaction mixture without a DNA template) were included in each PCR run. The positive controls were strain FRI 913 (sea sec sek sel tst lukED hlg), ATCC 51811 (seh), ATCC 49775 (seg sei sem sen seo), ATCC 31890 (lukM), NCTC 8325 (hla hld mecA), CCUG 47326 (fnbA fnbB), and DO-204 (sej) provided by Justus-Liebig-Universität, Giessen, Germany, and strains EELA-7 (sed seu) and EELA-2285195 (hlb).

Statistical methods.

A Pearson chi-square test was used to determine whether the presence of S. aureus at different sites of the teat (the teat canal, teat end, and teat wall) was associated with S. aureus IMI.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The fnbB gene of a teat orifice isolate was sequenced at the Institute of Biotechnology (Helsinki, Finland), and the sequence is available from GenBank under accession number FJ178640.

RESULTS

S. aureus growth in milk and in other samples.

In herd I, S. aureus IMI was detected in 26 quarters of 17 cows during the study period. About half of these infections were persistent infections (Table 2). During the period before the farm visit, S. aureus mastitis was detected in 8 cows (27%) and in 12 quarters (10%). At the time of the farm visit, S. aureus IMI was detected in 4 cows (15% of 27 cows) and 7 quarters (7% of 108 quarters). Twenty-eight percent of the samples from the other sites harbored S. aureus (Table 3); 48% of the quarters and 85% of the cows had S. aureus on the teat walls and teat orifices and/or in the teat canals. The presence of S. aureus in the teat canal (P < 0.01) and in the teat end (P < 0.05) was associated with S. aureus IMI. Eighty percent of the quarters that became infected with S. aureus during the study also had the bacterium on the teat skin and/or in the teat canals, whereas for those sites on the unaffected quarters, the respective figure was only 42%. Skin lesion specimens from seven cows (26%) supported the growth of S. aureus, and two of the cows had concomitant S. aureus mastitis. Two of the four randomly sampled milking liners were contaminated with S. aureus before milking. During the follow-up period after the farm visit, S. aureus mastitis was detected in 11 cows (37%) and in 14 quarters (12%).

TABLE 2.

Numbers of cows and quarters with S. aureus IMI and pulsotypes infecting quartersa

| Time point | Herd I

|

Herd II

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of infected cows/no. of infected quarters (no. of new infections) | Infecting pulsotype(s) (no. of infected quarters) | No. of infected cows/no. of infected quarters (no. of new infections) | Infecting pulsotype(s) (no. of infected quarters) | |

| Before farm visit | 8/12 (NDa) | A (8), B (4) | 5/5 (ND) | A2 (1), D (2), E2 (1), F (1) |

| During farm visit | 4/7 (1/3) | A (6), B (1) | 6/7 (3/4) | D (6), F (1) |

| After farm visit | 11/14b (8/11) | A (11), B (4) | 3/3 (2/2) | D (3) |

ND, not determined.

One quarter was infected with strains of pulsotypes A1 and B.

TABLE 3.

S. aureus isolates from herd I and their PFGE types grouped according to sample origin

| Origin of samples | No. of samples with S. aureus/total no. of samples (%) | No. (%) of PFGE-typed S. aureus isolates | PFGE type(s) (no. of isolates) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Milk | 37a (NDb) | 38 (100) | A1 (27), B (10), A1 and B (1) |

| Teat wall | 27/108 (25) | 9 (33) | A1 (7), B (1), A1 and B (1) |

| Teat orifice | 27/108 (25) | 13 (48) | A1 (10), B (3) |

| Teat canal | 32/108 (30) | 14 (44) | A1 (11), B (3) |

| Skin lesion | 7/8 (88) | 7 | A1 (1), B (5), A1 and B (1) |

| Liner before milking | 2/4 (50) | 2 | A1 (2) |

| Liner after milking | 28/108 (26) | 12 (43) | A1 (11), B (1) |

| Milkers' hands | 2/2 (100) | 2 | A1 (2) |

| Milkers' nostrils | 2/2 (100) | 2 | A1 (1), C (1) |

| Total | 165a (ND) | 99 (60) | A1 (72), B (23), A1 and B (3), C (1) |

Number of samples with S. aureus; includes follow-up samples taken after treatments.

ND, not determined.

In herd II, S. aureus was isolated from 10 cows and 11 quarters during the study period. Approximately half of the IMIs were new infections (Table 2). Five cows (9%) and five quarters (2%) had S. aureus mastitis before the farm visit. During the farm visit, 6 of the 51 cows (12%) had S. aureus IMIs, with 7 infected quarters (3% of 204). S. aureus was detected in 44% of samples from the other sites (Table 4). Ninety-six percent of the cows and 81% of the quarters had the bacterium on the teat skin or in the teat canals. The presence of S. aureus in the teat canal was associated with the presence of S. aureus in the milk (P < 0.01). Twenty-one cows had S. aureus in the skin lesion specimens, four cows having concomitant S. aureus IMIs. S. aureus mastitis was detected in three cows (6%) and in three quarters (1%) during the follow-up period after the farm visit.

TABLE 4.

S. aureus isolates from herd II and their PFGE types grouped according to sample origin

| Origin of samples | No. of samples with S. aureus/total no. of samples (%) | No. (%) of PFGE-typed isolates | PFGE type(s) (no. of isolates) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Milk | 21a (NDb) | 21 (100) | D (17), F (2), A2 (1), E2 (1) |

| Teat wall | 131/204 (64) | 43 (34) | D (38), E1 (2), A2 (1), B (1), F (1) |

| Teat orifice | 130/192 (68) | 37 (28) | D (33), F (2), A2 (1), B (1) |

| Teat canal | 35/191 (18) | 20 (57) | D (16), B (2), A2 (1), F (1) |

| Skin lesion | 26/33 (79) | 26 (100) | D (24), E1 (1), F (1) |

| Liner before milking | 0/32 (0) | 0 | |

| Liner after milking | 48/186 (26) | 40 (83) | D (38), B (1), E1 (1) |

| Milkers' hands | 0/2 (0) | 0 | |

| Milkers' nostrils | 3/4 (75) | 3 | D (2), G (1) |

| Total | 390a(ND) | 192 (49) | D (168), F (7), B (5), A2 (4), E1 (4), E2 (1), G (1) |

Number of samples with S. aureus; includes follow-up samples taken after treatments.

ND, not determined.

Comparison of S. aureus pulsotypes between and within herds.

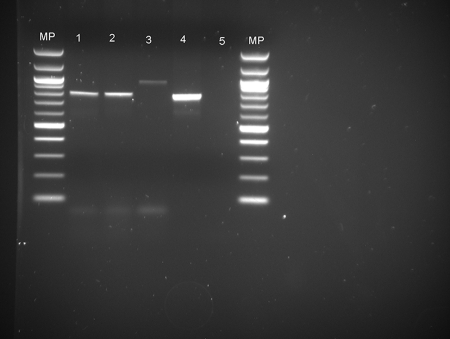

PFGE typing produced nine fingerprints, which were classified as pulsotypes A1 to G (Fig. 1). Pulsotypes A1 (from herd I) and A2 (from herd II) and pulsotypes E1 and E2 (from herd II) were considered to be possibly related, with four band differences. Pulsotype B was detected in both herds.

FIG. 1.

Dendrogram showing the genetic relatedness of S. aureus pulsotypes A1 to G observed in herds I and II during the study period. Numbers at the upper left indicate percent similarity.

In herd I, S. aureus pulsotypes A1 and B were isolated from milk samples throughout the study (Table 2). Pulsotype A1 caused mastitis in 13 cows (19 quarters). In six of those cows (eight quarters), the same pulsotype was detected several times in the same quarter, indicating persistent IMI. Pulsotype A1 predominated in samples from the extramammary sites (Table 3) and was detected in 90% of S. aureus-positive cows. Pulsotype A was present on the teat skin and/or in the teat canals of six cows without S. aureus IMI. Pulsotype B caused mastitis in eight cows (eight quarters). At the time of the farm visit, pulsotype B was isolated from extramammary sites in three healthy cows. Pulsotype B was common in the skin lesion samples. Indistinguishable pulsotypes were isolated from quarter milk and teat skin samples and/or teat canal samples from the same cows. The same pulsotype was found in skin lesion samples and milk samples from the same cows. For two cows, pulsotypes A1 and B were isolated from milk samples obtained from different quarters at the same time. Milk from a single quarter of one cow harbored pulsotypes A1 and B.

In herd II, pulsotype D was continuously isolated from milk during the study period (Table 2). Pulsotype D caused mastitis in seven cows (eight quarters) and was isolated several times from the milk of three cows. At the farm visit, pulsotype D was present in the extramammary sites in 41 cows. Two preparturient heifers sampled had pulsotype D in the colostrum and on the teat skin, and all three heifers had it on the skin lesions. Pulsotype F was found together with pulsotype D in the extramammary sites in four cows, and pulsotype E1 was found in the extramammary sites in three. For one cow, pulsotype F was repeatedly isolated from the same mastitis quarter. Pulsotypes A2, B, and E2 were sporadic; each of them was isolated from a single cow. Six cows had S. aureus strains of unrelated pulsotypes in the milk samples and the teat skin or teat canal samples from the same quarter, but the pulsotype found in milk was also present on the skin of another quarter. The same pulsotype, D, was found in skin lesion specimens and milk samples from the same cows. Two cows had pulsotype D in the teat canals and on the teat skin, and these quarters developed mastitis caused by that pulsotype after the sampling day.

In 25 samples, variations in colony morphology, color, or the hemolysis phenotype were visually detected. To examine whether the colony variants represented different pulsotypes, two colonies from each of these samples were PFGE typed. Except for three samples from herd I (milk, teat skin, and skin lesion samples) (Table 3), each sample had only one pulsotype.

S. aureus virulence genes.

Variations in the gene profiles among the most common pulsotypes, A1, B, and D, were observed. The individual genes or the different gene profiles of multiple S. aureus isolates were not linked with the origins of the isolates.

Pulsotype A1 isolates from the cows and the milking liners of herd I (n = 72) had hla-hlg, lukED, fnbA, and fnbB and, with one exception, blaZ, sed, and sej but seldom had lukM (n = 8), and only one pulsotype A1 isolate had sem and seo. Pulsotype A1 isolates from milkers' hands (n = 2) and nostrils (n = 1) were positive for hla-hlg, lukED, fnbA, fnbB, blaZ, sed, and sej, as were pulsotype A1 isolates from the cows. Pulsotype B isolates from herd I (n = 26) had hla-hlg, lukED, lukM, fnbA, seg, and sei, and the majority (n = 19) had sem-seo; seu was detected in nine strains, and blaZ was detected in two (from milk and skin lesion samples), but sed or sej was detected in none. A pulsotype C isolate from a human nostril had a unique gene profile (hla hld hlg lukED fnbA sec sel seg sei tst).

In herd II, pulsotype A2 isolates (n = 4) carried only hla, hld, hlg, lukED, and fnbA. Pulsotype B isolates from herd II (n = 5) possessed hla-hlg, lukED, lukM, fnbA, seg, sei, sem-seo, seu, sec, sel, and tst. All of the 105 PCR-screened pulsotype D strains harbored hla, hld, hlg, fnbA, and fnbB, and 103 had lukED, but only a few were positive for lukM (n = 4), blaZ (n = 3), seg and sei (n = 2), sed (n = 1), sem (n = 1), or seo (n = 1). Pulsotype D isolates found in the nostrils of two milkers were positive for hla, hld, hlg, lukED, lukM, fnbA, and fnbB. Pulsotype E1 strains (n = 4) were positive for hla, hld, hlg, lukED, fnbA, blaZ, seg, sei, sem-seo, and seu. The pulsotype E2 isolate carried hla, hld, hlg, lukED, fnbA, seg, and sei. The genes hla, hld, hlg, lukED, fnbA, blaZ, sea, seh, and sek were detected in pulsotype F strains (n = 7). Pulsotype G from the nostrils of the third milker harbored hla, hld, hlg, lukED, lukM, fnbA, seg, sei, sem-seo, and seu.

No strains with mecA were detected.

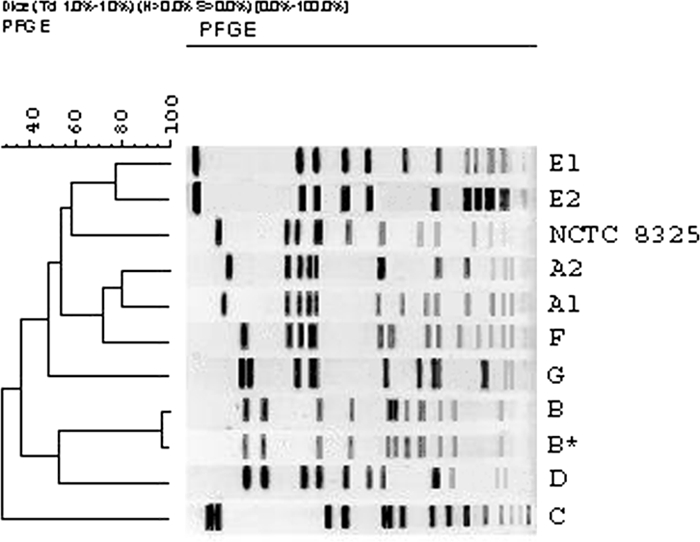

For one S. aureus isolate of pulsotype E1 originating from mastitic milk and one isolate of pulsotype D from a teat orifice, the PCR amplification products for fnbB were heavier than the corresponding fragment of the positive control (Fig. 2). The amplification products of the teat orifice isolate were submitted to the Institute of Biotechnology (Helsinki, Finland) for sequencing. The sequence was exported into Chromas Lite version 2.01 (Technelysium Pty. Ltd., Australia). The sequence was sent to GenBank (accession no. FJ178640) and is 90% identical to the corresponding GenBank sequences of fibronectin-binding protein genes in S. aureus strains Mu3 (accession no. NC_009782) and Mu50 (accession no. NC_002758).

FIG. 2.

Agarose gel electrophoresis analysis showing PCR amplification products for the fnbB gene of S. aureus. Lanes: MP, DNA molecular size markers; 1 and 2, fnbB-positive isolates 774 and 196; 3, fnbB variant (teat orifice isolate); 4, fnbB-positive control CCUG 47326; and 5, negative control.

DISCUSSION

The presence of S. aureus in sites of IMI and at extramammary sites in two herds in which the pathogen continuously caused mastitis was investigated. The proportion of animals harboring S. aureus on their udder skin was very high in both herds. The contamination of milking equipment by S. aureus was common, and the bacterium was also isolated from the hands and nostrils of milkers. In both herds, the majority of S. aureus isolates comprised predominant genotypes, which were unique to the herds. The number of pulsotypes in herd II (an open herd), which included heifers raised off site, was higher (n = 7) than that in herd I (a closed herd; n = 3). Our results agree with those of Middleton et al. (24), who also found more heterogeneity among S. aureus isolates from an open herd than among those from a closed herd. Nearly all strains subjected to PCR analysis carried genes for alpha-, beta-, and gamma-hemolysin and the genes lukED and fnbA. The other genes were less frequent and pulsotype linked within the herd, but no connection between specific virulence genes and the origin of the isolate was found. In both herds, strains of the predominant pulsotypes typically possessed fnbA and fnbB, whereas only fnbA was present in the other types. The results from both PFGE typing and PCR showed that strains with genotypes indistinguishable from those of strains in sites of mastitis also dominated extramammary sites within both herds.

The high prevalence of S. aureus on teat skin and in canals indicates that virtually all cows in these herds could have exposure to this pathogen via their own skin. Postmilking teat dipping, practiced for both herds, did not appear to prevent the growth of S. aureus on the teats. The efficacy of the teat dips may not be as good under field conditions as under experimental conditions, as recently shown in a Norwegian field study (49). In herd II, extramammary sites may be more likely routes of transmission than milk from infected quarters. It was easier to maintain a milking order for this stanchion-barn herd than for herd I, with its loose-housing system. This circumstance may indicate that postmilking liner contamination by S. aureus, seen after the milking of most of the cows, originated from the teat skin and teat canals of healthy cows.

We were able to detect very small numbers of S. aureus CFU by using a selective enrichment method. This strategy was possibly one reason for the high level of recovery of S. aureus from the extramammary sites, a phenomenon that was reported by Matos et al. (22). Although only a small percentage of these cows developed S. aureus IMI during the study period, IMI may be more likely if bacteria are present around the teat orifice than if the teats are free from S. aureus. This trend was directly demonstrated in two of the cows, for which the same pulsotype that infected the udder quarter was also isolated from the teat skin prior to IMI. Cows with teat canals colonized by S. aureus are at particular risk of developing mastitis; one-third of the mammary quarters in herd I had S. aureus in the teat canals, which may be one reason for the high number of new infections in this herd. Furthermore, tissues affected by teat abrasions and teat traumas in particular are likely to contain high numbers of S. aureus (27), and teat lesions are common in many herds. In our study herds, the skin lesions harbored the same S. aureus strains as the milk from the same cows with IMIs.

Zadoks et al. (50) typed S. aureus isolates collected from sites of IMIs, teat skin, teat canals, milking equipment, and milking personnel for 43 herds by using PFGE and binary typing. The number of isolates varied from 1 to 20 per herd. Based on the complete data, the majority of teat skin isolates were different from those infecting the udders. The authors concluded that specific udder-pathogenic S. aureus strains exist and are mostly different from those present on the udder skin. In our study, the results largely contradict their findings but agree with those of Jørgensen et al. (17), who reported that the genotypes of strains from IMI sites and teat skin were indistinguishable by PFGE typing. In our herds, genotypes that probably were best adapted to multiplying on the teat skin, in the teat canals, and in skin lesions also caused most IMIs. Occasional exceptions were one sporadic genotype (E2) in herd II that was isolated only from milk and two other genotypes (B and E1) that were detected only on the teat skin and were not isolated from sites of IMI.

To the best of our knowledge, only one previous study comparing virulence characteristics of S. aureus strains isolated from IMI sites and extramammary sites is available (8). The authors found milk-associated S. aureus genotypes to be more likely to produce biofilm than genotypes associated with extramammary sources (teat skin and milking liners). In our study, no association between the sample origin and virulence genes was established. However, in both herds, the genes fnbA and fnbB, encoding fibronectin-binding proteins (FnBPs), coexisted in the most common strains, those of pulsotypes A1 and D. In other pulsotypes, which were less frequent, only fnbA was detected. In the work of Salasia et al. (36), fnbA was more common than fnbB in S. aureus isolates originating from cows with bovine mastitis in Indonesian and German dairy herds. The proteins FnBPA and FnBPB enable the attachment of S. aureus to host tissues, facilitate the invasion of the organism into epithelial cells (4, 48), and are involved in the colonization of other surfaces like medical devices (11). Strains not expressing FnBPA and FnBPB were demonstrated previously to have highly reduced abilities to invade bovine mammary epithelial cells in vitro (5). It is speculated that S. aureus genotypes predominant in dairy herds can exhibit high colonization and survival rates in bovine hosts, which favors a benign relationship between the microbe and the host animal. In herd II in particular, pulsotype D may have benefited from its possibly high potential for adherence and may have therefore become predominant. Other explanations for the finding that a strain with a small number of virulence genes could resist competition with other strains are hard to find.

The genes for superantigens were ubiquitous in isolates from herd I. The predominant genotype, A1, typically isolated from cows with persistent infections, carried enterotoxin-encoding genes sed and sej and the gene for penicillin resistance, blaZ. The prognosis for mastitis caused by penicillin-resistant S. aureus strains is poor (38, 42), and wider spreading of these strains may be expected if they are present also at the extramammary sites. Furthermore, the presence of the blaZ gene has been thought to indicate the coexistence of some other virulence factor(s), which together with blaZ may contribute to the persistence of S. aureus in the mammary gland (13). In our previous study, the responses of IMIs caused by blaZ-positive strains to treatment tended to vary among different pulsotypes, but strains that carried sed, sej, and blaZ were overrepresented in chronic IMIs (13). Superantigens such as enterotoxins have been suggested to enhance the persistence of bovine IMI due to their immunosuppressive effect on the host animal (6). The use of antimicrobials in the herds may also have an impact; antimicrobials like β-lactams and fluoroquinolones have been shown in vitro to stimulate HLA production by S. aureus (29), and this effect may be possible for enterotoxins as well.

Many factors contribute to the selection and diversity of S. aureus strains in herds. The number and diversity of S. aureus strains is likely to increase if new strains are introduced via cattle import, as shown here for herd II, in agreement with the results of Middleton et al. (24). Sommerhäuser et al. (39) proposed that the successful control of contagious mastitis may increase the diversity but decrease the spread of strains within the herd and that failure in control may lead to the dissemination of only one or a few dominant strains throughout the herd. Preparturient heifers can be an important reservoir of S. aureus, and strains originating from their skin have been shown to cause IMI in cows of the same herd (24). However, heifers can also harbor different strains from those in lactating cows (50). In our study, two precalving heifers in herd II harbored S. aureus in the colostrum, and the strains were similar to those isolated from lactating cows.

Milking personnel may also carry the same S. aureus types as the cows, as noted here for both herds, but the origin of the colonization remains unknown. However, the findings from recent epidemiological studies of human and animal S. aureus strains, including bovine mastitis isolates, suggest host specificity, although a high degree of variation within and between S. aureus clonal lineages originating from different host animals was found (2, 14, 41, 45). A recent study by Herron-Olson et al. (14) showed that strains from cattle with S. aureus mastitis carried several unique genes, which may be suggested to play a role in the adaptation of the strains to the bovine udder. Some other genes, such as bap, involved in biofilm formation, and gene complexes like the immune evasion cluster may be less important for IMI, as these genes are rare in bovine isolates, in contrast to human isolates (25, 41).

In conclusion, the S. aureus strains causing bovine IMI were not different from those isolated from extramammary sites. Teat skin and especially the teat canals were important potential reservoirs of S. aureus causing IMI. This information may be useful in planning mastitis control strategies for herds suffering from S. aureus mastitis. However, identical pulsotypes from different herds may harbor different virulence and resistance genes, and placing these types in the same virulence class may be an oversimplification. The relative significance of different genes is poorly understood and should be further studied in larger populations.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the laboratory personnel of the Finnish Food Safety Authority, Marja-Liisa Tasanko from the laboratory of the Ambulatory Clinic, Taina Lehto from the laboratory of Viikki at the Department of Production Animal Medicine at Helsinki University, and Paula Collin-Olkkonen at the Institute of Biotechnology, Helsinki, for generous help and advice. All farm personnel participating in the study are warmly thanked. Christoph Lämmler from Justus-Liebig-Universität, Giessen, Germany, kindly provided us with the control strain for sej.

This work was supported by grants from the Walter Ehrström Foundation, Orion-Farmos Finland, the Mercedes Zachariassen Foundation, and the Finnish Dairy Association.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 September 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aarestrup, F. M., H. D. Larsen, N. H. Eriksen, C. S. Elsberg, and N. E. Jensen. 1999. Frequency of alpha- and beta-haemolysin in Staphylococcus aureus of bovine and human origin. A comparison between pheno- and genotype and variation in phenotypic expression. APMIS 107425-430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben Zakour, N. L., D. E. Sturdevant, S. Even, C. M. Guinane, C. Barbey, P. D. Alves, M. Cochet, M. Gautier, M. Otto, J. R. Fitzgerald, and Y. Le Loir. 20 June 2008. Genome-wide analysis of ruminant Staphylococcus aureus reveals diversification of the core genome. J. Bacteriol. doi: 10.1128/JB.01984-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Brakstad, O. G., K. Aasbakk, and J. A. Maeland. 1992. Detection of Staphylococcus aureus by polymerase chain reaction amplification of the nuc gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 301654-1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brouillette, E. G., B. G. Talbot, and F. Malouin. 2003. The fibronectin-binding proteins of Staphylococcus aureus may promote mammary gland colonization in a lactating mouse model of mastitis. Infect. Immun. 712292-2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dziewanowska, K., J. M. Patti, C. F. Deobald, K. W. Bayles, W. R. Trumble, and G. A. Bohach. 1999. Fibronectin binding protein and host cell tyrosine kinase are required for internalization of Staphylococcus aureus by epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 674673-4788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferens, W. A., and G. A. Bohach. 2000. Persistence of Staphylococcus aureus on mucosal membranes: superantigens and internalization by host cells. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 135225-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fitzgerald, J. R., and J. M. Musser. 2001. Evolutionary genomics of pathogenic bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 9547-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fox, L. K., R. N. Zadoks, and C. T. Gaskins. 2005. Biofilm production by Staphylococcus aureus associated with intramammary infection. Vet. Microbiol. 107295-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fournier, C., P. Kuhnert, J. Frey, R. Miserez, M. Kirchhofer, T. Kaufmann, A. Steiner, and H. U. Graber. 20 March 2008, posting date. Bovine Staphylococcus aureus: association of virulence genotypes and clinical outcome. Res. Vet. Sci. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Fueyo, J. M., M. C. Mendoza, M. R. Rodicio, J. Muniz, M. A. Alvarez, and M. C. Martin. 2005. Cytotoxin and pyrogenic toxin superantigen profiles of Staphylococcus aureus associated with subclinical mastitis in dairy cows and relationships with macrorestriction genomic profiles. J. Clin. Microbiol. 431278-1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greene, C., D. McDevitt, and P. Francois. 1995. Adhesion properties of mutants of Staphylococcus aureus defective in fibronectin-binding proteins and studies on the expression of fnb genes. Mol. Microbiol. 171143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haveri, M., S. Suominen, L. Rantala, T. Honkanen-Buzalski, and S. Pyörälä. 2005. Comparison of phenotypic and genotypic detection of penicillin G resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine intramammary infection. Vet. Microbiol. 10697102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haveri, M., A. Roslöf, and S. Pyörälä. 2007. Virulence genes of bovine Staphylococcus aureus from persistent and nonpersistent intramammary infections with different clinical characteristics. J. Appl. Microbiol. 103993-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herron-Olson, L., J. R. Fitzgerald, J. M. Musser, and V. Kapur. 2007. Molecular correlates of host specialization in Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS ONE 2e1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hogan, J. S., R. N. González, R. J. Harmon, S. C. Nickerson, S. P. Oliver, J. W. Pankey, and K. L. Smith. 1999. Laboratory handbook on bovine mastitis, revised ed. The National Mastitis Council, Madison, WI.

- 16.Jarraud, S., M. C. Mougel, J. Thioulouse, G. Lina, H. Meugnier, F. Forey, X. Nesme, J. Etienne, and F. Vandenesch. 2002. Relationships between Staphylococcus aureus genetic background, virulence factors, agr groups (alleles), and human disease. Infect. Immun. 70631-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jørgensen, H. J., T. Mørk, and L. M. Rørvik. 2005. The occurrence of Staphylococcus aureus on a farm with small-scale production of raw milk cheese. J. Dairy Sci. 883810-3817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klastrup, O., and P. Schmidt Madsen. 1974. Nordic recommendations for mastitis examinations of gland samples. Nord. Vet. Med. 26197-204. [In Danish.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lancette, G. A., and S. R. Tatini. 1992. Staphylococcus aureus, p. 533-550. In C. Vanderzant and D. F. Splittstoesser (ed.), Compendium of methods for the microbiological examination of foods. American Public Health Association, Washington, DC.

- 20.Letertre, C., S. Perelle, F. Dilasser, and P. Fach. 2003. Identification of a new putative enterotoxin SEU encoded by the egc cluster of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 9538-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lina, G., Y. Piemont, F. Godail-Gamot, M. Bes, M. O. Peter, V. Gauduchon, F. Vandenesch, and J. Etienne. 1999. Involvement of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-producing Staphylococcus aureus in primary skin infections and pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 291128-1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matos, J. S., D. G. White, R. J. Harmon, and B. E. Langlois. 1991. Isolation of Staphylococcus aureus from sites other than the lactating mammary gland. J. Dairy Sci. 741544-1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mehrotra, M., G. Wang, and W. Johnson. 2000. Multiplex PCR for detection of genes for Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins, exfoliative toxins, toxic shock syndrome toxin 1, and methicillin resistance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 381032-1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Middleton, J., L. Fox, J. Gay, J. Tyler, and T. Besser. 2002. Use of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for detecting differences in Staphylococcus aureus strain populations between dairy herds with different cattle importation practices. Epidemiol. Infect. 129387-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monecke, S., P. Kuhnert, H. Hotzel, P. Slickers, and R. Ehricht. 2007. Microarray based study on virulence-associated genes and resistance determinants of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from cattle. Vet. Microbiol. 125128-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murchan, S., M. E. Kauffmann, A. Deplano, R. de Ryck, M. Struelens, C. E. Zinn, V. Fussing, S. Salmenlinna, J. Vuopio-Varkila, N. El Soth, C. Cuny, W. Witte, P. T. Tassios, N. Legakis, W. van Leeuwen, A. van Belkum, A. Vindel, I. Laconcha, J. Garaizar, S. Häggman, B. Olsson-Liljequist, U. Ramsjö, G. Coombes, and B. Cookson. 2003. Harmonization of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocols for epidemiological typing of Staphylococcus aureus: a single approach developed by consensus in 10 European laboratories and its application for tracing the spread of related strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 411574-1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myllys, V., T. Honkanen-Buzalski, H. Virtanen, S. Pyörälä, and H.-P. Müller. 1994. Effect of abrasion of teat orifice epithelium on development of bovine staphylococcal mastitis. J. Dairy Sci. 77446-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nashev, D., K. Toshkova, S. I. Salasia, A. A. Hassan, C. Lämmler, and M. Zschöck. 2004. Distribution of virulence genes of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from stable nasal carriers. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 23345-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohlsen, K., W. Ziebuhr, K. P. Koller, W. Hell, T. A. Wichelhaus, and J. Hacker. 1998. Effects of subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics on alpha-toxin (hla) gene expression of methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 422817-2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Østerås, O., L. Sølverød, and O. Reksen. 2006. Milk culture results in a large Norwegian survey—effects of season parity, days in milk, resistance and clustering. J. Dairy Sci. 891010-1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patti, J. M., B. L. Allen, M. J. Gavin, and M. Höök. 1994. MSCRAMM-mediated adherence of micro-organisms to tissues. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 48585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pitkälä, A., M. Haveri, S. Pyörälä, V. Myllys, and T. Honkanen-Buzalski. 2004. Bovine mastitis in Finland 200—prevalence, distribution of bacteria, and antimicrobial resistance. J. Dairy Sci. 872433-2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Projan, S. J., and R. P. Novick. 1997. The molecular basis of pathogenicity, p. 55-81. In K. B. Crossley and L. G. Archer (ed.), The staphylococci of human disease. Churchill Livingstone Inc., New York, NY.

- 34.Rainard, P., J. C. Corrales, M. B. Barrio, T. Cochard, and B. Poutrel. 2003. Leucotoxic activities of Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from cows, ewes, and goats with mastitis: importance of LukM/LukF′-PV leukotoxin. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 10272-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberson, J. R., K. L. Fox, D. D. Hancock, J. M. Gay, and T. E. Besser. 1994. Ecology of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from various sites of dairy farms. J. Dairy Sci. 773354-3364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salasia, S. I., Z. Khusnan., C. Lämmler, and M. Zschöck. 2004. Comparative studies on pheno- and genotypic properties of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine subclinical mastitis in central Java in Indonesia and Hesse in Germany. J. Vet. Sci. 5103-109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salmenlinna, S., O. Lyytikainen, P. Kotilainen, R. Scotford, E. Siren, and J. Vuopio-Varkila. 2000. Molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Finland. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 19101-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sol, J., O. C. Sampimon, H. W. Barkema, and Y. H. Schukken. 2000. Factors associated with cure after therapy of clinical mastitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. J. Dairy Sci. 83278-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sommerhäuser, J., B. Kloppert, W. Wolter, M. Zschöck, A. Sobiraj, and K. Failing. 2003. The epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus infections from subclinical mastitis in dairy cows during a control programme. Vet. Microbiol. 9691-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smyth, D. S., P. J. Hartigan, W. J. Meaney, J. R. Fitzgerald, C. F. Deobald, G. A. Bohach, and C. J. Smyth. 2005. Superantigen genes encoded by the egc cluster and SaPIbov are predominant among Staphylococcus aureus isolates from cows, goats, sheep, rabbits and poultry. J. Med. Microbiol. 54401 -411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sung, J. M., D. H. Lloyd, and J. A. Lindsay. 2008. Staphylococcus aureus host specificity: comparative genomics of human versus animal isolates by multi-strain microarray. Microbiology 1541949-1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taponen, S., A. Jantunen, E. Pyörälä, and S. Pyörälä. 2003. Efficacy of targeted 5-day combined parenteral and intramammary treatment of clinical mastitis caused by penicillin-susceptible or penicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Acta Vet. Scand. 4453-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tenhagen, B.-A., G. Köster, J. Wallmann, and W. Heuwieser. 2006. Prevalence of mastitis pathogens and their resistance against antimicrobial agents in dairy cows in Brandenburg, Germany. J. Dairy Sci. 892542-2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 332233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Leeuwen, W. B., D. C. Melles, A. Alaidan, M. Al-Ahdal, H. A. M. Boelens, S. V. Snijders, H. Wertheim, E. van Duijkeren, J. K. Peeters, P. J. van der Spek, R. Gorkink, G. Simons, H. A. Verbrugh, and A. van Belkum. 2005. Host- and tissue-specific pathogenic traits of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 1874584-4591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vesterholm-Nielsen, M., M. Ø. Larsen, and J. E. Olsen. 1999. Occurrence of blaZ gene in penicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine mastitis in Denmark. Acta Vet. Scand. 40279-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.von Eiff, C., A. W. Friedrich, G. Peters, and K. Becker. 2004. Prevalence of genes encoding for members of the staphylococcal leukotoxin family among clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 49157-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wesson, C. A., L. E. Liou, K. M. Todd, G. A. Bohach, W. M. Trumble, and K. W. Bayles. 1998. Staphylococcus aureus agr and sar global regulatorsinfluence internalization and induction of apoptosis. Infect. Immun. 665238-5243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whist, A. C., O. Österås, and L. Solverod. 2006. Clinical mastitis in Norwegian herds after a combined selective dry-cow therapy and teat-dipping trial. J. Dairy Sci. 894649-4659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zadoks, R. N., W. B. van Leeuwen, D. Kreft, L. K. Fox, H. W. Barkema, Y. H. Schukken, and A. van Belkum. 2002. Comparison of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from bovine and human skin, milking equipment, and bovine milk by phage typing, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, and binary typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 403894-3902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zschöck, M., K. Risse, and J. Sommerhäuser. 2004. Occurrence and clonal relatedness of sec/tst-gene positive Staphylococcus aureus isolates of quartermilk samples of cows suffering from mastitis. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 38493-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]