Abstract

Clostridium difficile is the leading cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and pseudomembranous colitis, which have significant morbidity and mortality. Accurate and timely diagnosis is critical. Repeat enzyme immunoassay testing for C. difficile toxin has been recommended because of <100% sensitivity. All C. difficile tests between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2006 were retrospectively analyzed for results and testing patterns. The Wampole C. difficile Tox A/B II enzyme immunoassay kit was used. There were a total of 8,256 tests from 3,112 patients; 49% of tests were repeated. Of the 3,749 initially negative patient tests, 96 were positive upon repeat testing within 10 days of the first test. Of repeat tests, 0.9% repeated on day 0 (same day as the first test), 1.8% on day 1, 3.8% on day 2, 2.6% on day 3, 5.4% on days 4 to 6, and 10.6% on days 7 to 10 were positive. Thirty-eight patients had a positive test within 48 h of an initial negative test, and based on chart review, 18 patients were treated empirically while 16 were treated following the new result. None had evidence of medical complications. Of initially positive patients, 91% were positive upon repeat testing on day 0, 75% on day 1, and 58% on day 2, to a low of 14% on days 7 to 10. Depending on the clinical setting, these data support not repeating C. difficile tests within 2 days of a negative result and limiting repeat testing to ≥1 week of a positive result.

Clostridium difficile is an anaerobic, gram-positive, spore-forming bacillus associated with pseudomembranous colitis. This toxin-producing bacterium is recognized as the primary cause of nosocomial infectious diarrhea, with a reported incidence of approximately 0.7/1,000 hospital discharges (8). This bacterium is capable of producing both an enterotoxin, toxin A, and a cytotoxin, toxin B. In addition to C. difficile spore ingestion and toxin production, an alteration of the normal colonic flora, typically caused by prior antibiotic use, is needed for clinical disease (2, 8, 11). The most frequently associated predisposing antibiotics include, but are not limited to, ampicillin, amoxicillin, cephalosporins, and clindamycin (8, 17). Infection can range from asymptomatic carriage to moderate diarrhea to life-threatening pseudomembranous colitis. The incubation period is typically less than 1 week from acquisition. The gold standard diagnostic method is tissue culture cytotoxin assay (8). Unfortunately, this can delay diagnosis by up to 2 to 3 days. Currently, enzyme immunoassay (EIA) is the most commonly used testing method because of its relatively low cost, rapid turnaround, and high specificity (12, 13, 20, 21, 26). However, the reportedly “low” sensitivity in the range of 70 to 90% has led to the concern of false-negative results (10, 15, 24).

In our institution, we have observed an increasing number of EIAs being ordered within a short time, including two to three stool samples being sent per day for the same patient. In 1995, Manabe et al. (14) reported the need to test successive stool specimens in order to increase the diagnostic yield. They found that 72% of patients with C. difficile were positive by EIA on the first run and that 10% of positive patients were missed by EIA compared to tissue culture cytotoxicity assay (14). In 1997, published practice guidelines stated that when C. difficile is clinically suspected, a single stool specimen should be sent for testing; however, if the result is negative, one to two additional stools should be sent for retesting (7). Similar recommendations were published stating that “performing enzyme immunoassays on two to three specimens rather than one… increases the diagnostic yield by 5 to 10%” (3). This diagnostic concern is further exemplified by the recent Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) recommendations for a two-step testing algorithm (6). This clinical impression that C. difficile is frequently underdiagnosed has led physicians in our institution to often order “C. diff x 3” in an attempt to improve diagnostic accuracy.

In a study similar to ours, Mohan et al. (16) found that out of 78 patients, only one became positive upon repeat EIA testing for toxin A/B within a 7-day period. They concluded that if the initial test is negative, “repeat testing is unnecessary and not cost-effective” (16). Additional reports also promote less-frequent testing (5, 19, 25). The aim of our study was to analyze the test ordering patterns within our institution to determine if frequent repeat testing is warranted.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All patients were tested for C. difficile between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2006 at the Shands at the University of Florida Hospital and the Shands at Alachua General Hospital in Gainesville, FL. C. difficile testing was performed with the Wampole (TechLab) C. difficile Tox A/B II EIA kit, which uses a microplate assay with 96 wells that are coated with affinity-purified goat antibodies with specificity for toxins A and B. The tests were run according to the manufacturer's protocol (C. Wampole, C. difficile Tox A/B II package insert). All patients who had only one C. difficile test, either negative or positive, were excluded from further analysis. Those with an initial negative C. difficile EIA result were categorized by their C. difficile test results for a subsequent sample(s) for tests performed on the same day (separate sample) as the initial test (day 0), the next day (day 1), and so on, for the following 10 days. For completeness, a similar analysis was carried out for those patients whose first test result was positive.

While we were primarily concerned about the yield of repeat testing of subsequent samples within the same day or the next few days, we included patients retested within a 10-day period from the time of any negative test in the overall analysis. We carried out the same analysis excluding patient samples tested within a 3-month period following the initial test, to exclude possible bias from an earlier positive episode of C. difficile. We also performed the same analysis on our bone marrow transplant patients, whose highly immunocompromised state might amplify the problems of an initially false-negative result.

All the data subsets were analyzed using a 2 × 6 chi-square contingency table. If this analysis demonstrated statistical significance, individual 2 × 2 chi-square analysis with the Yates correction was performed to determine which of the subsequent time frames were statistically different from either day 0 or day 0 and day 1 combined.

A complete (paper and electronic) chart and pharmacy review was performed for all patients whose C. difficile test result changed from negative to positive within 48 h of the initial negative test.

RESULTS

Immunoassay results and testing patterns.

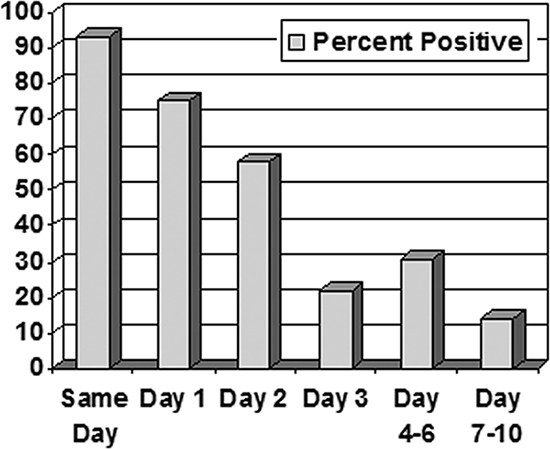

A total of 8,256 C. difficile EIAs for 3,112 patients were performed in 2006. There were 4,181 “test episodes” based on the definition of the 10 days following an initial test. Of those episodes, there were 1,948 in which only a single test was performed and was negative and 187 with a positive result with no subsequent sample tested in the following 10-day period. That left 4,075 tests (49%) which were considered repeat sampling and testing within an encounter. Of the repeat tests, the number of subsequently submitted specimens that changed the patient's status from testing negative to testing positive was 96 out of 3,749 (2.6%). When divided into a timeline, the percent conversion to positive upon repeat sampling and testing steadily increased from 0.9% on the same day to a high of 10.6% by days 7 to 10, with the exception of day 3 (Table 1). Conversely, ensuing tests performed on patient samples following an initial positive result showed a slow decline in positive results over the 10 days (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Percent conversion of initial negative test results to subsequent positive results

| Day(s) | % Conversion (no. of samples positive/total no. of samples)a

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients

|

Bone marrow transplant patients

|

|||

| All samples | Excluding samples from 3 mo after previous positive test | All samples | Excluding samples from 3 mo after previous positive test | |

| 0 (same day) | 0.9 (8/855) | 0.6 (4/593) | 2.2 (6/279) | 1.7 (3/171) |

| 1 | 1.8 (30/1,670) | 1.2 (14/1,146) | 2.8 (5/179) | 1.0 (1/98) |

| 2 | 3.8 (20/529) | 3.8 (14/370) | 1.7 (1/58) | 2.4 (1/41) |

| 3 | 2.6 (6/231) | 3.6 (6/169) | 0 (0/20) | 0 (0/17) |

| 4-6 | 5.4 (18/332) | 6.0 (13/217) | 4.2 (2/47) | 8.8 (3/34) |

| 7-10 | 10.6 (14/132) | 7.1 (6/84) | 10.0 (3/28) | 8.0 (2/25) |

P < 0.0005, all groups. See text for details.

FIG. 1.

The graph demonstrates a steady decline in percent positive results over the next 10 days after an initial positive result.

Following exclusion of samples collected in the 3 months following a positive test result, there were a total of 6,058 tests run and 3,269 “test episodes.” There were 1,777 encounters in which, following the initial negative or positive test, no additional specimens were collected and tested. Out of the 6,058 tests, 46% (2,789 tests) were considered repeat patient testing. Following an initial negative result, the percent conversion to positive in subsequent samples was similar to that of the nonexclusion group above (Table 1), but to a slightly lesser degree since the bias of a priori testing had been removed. The rate of positive decline upon repeat testing during an encounter was also similar to that for the nonexclusion group.

In 2006, our institution performed 1,006 C. difficile EIAs for 170 patients in our Bone Marrow Unit. There were a total of 345 “test episodes,” of which 84 had negative results and nine had positive results without subsequent testing. Sixty-six percent (661) of tests were considered repeat sampling and testing. Although the conversion rate from a negative to a positive result in a successive sample was slightly higher initially, the overall trend over the 10-day encounter was similar to the previous data presented (Table 1). With the 3-month exclusion, there were a total of 622 tests run, of which 412 were repeats (66%). An analogous trend was seen in comparing the rates of conversion from a negative to a subsequent positive result (Table 1). Additionally, there was a similar repeat-positive decline over the 10-day period.

Analysis of repeat testing of initially negative specimens.

There was statistical significance when analyzing all tested sample data by a 2 × 6 chi-square contingency table (chi-squares = 61.2502, degrees of freedom [df] = 5, P = <0.0005), and in analyzing the data following the 3-month exclusion there was also statistical significance (chi-squares = 41.1020, df = 5, P = <0.0005). When determining if there was statistical significance between the individual days using a 2 × 2 chi-square table, we found that there was no statistically significant difference between day 0 and day 1 (for either data set). However, there was a significant difference between day 0 and day 2 and between days 0 and 1 combined and day 2 (chi-squares = 11.948, df = 1, P = 0.0005, and chi-squares = 10.967, df = 1, P = 0.0009, respectively). The same analysis was performed on the data obtained solely from the bone marrow transplant patients; however, the data set was too small to demonstrate statistical significance.

Review of clinical data.

Out of the 38 patients who had a subsequent sample test positive within 48 h of an initial negative test, 18 patients were treated empirically due to clinical suspicion and 16 were treated following the new result. For the latter 16 patients, there was no evidence of complications. One of the patients died approximately 16 days later, secondary to enterococcus pneumonia and aspergillosis. Of the 34 treated patients, 14 had histories of a prior episode of C. difficile colitis. The clinical management did not change in the remaining four untreated patients with a changed test result. Of note, three were clinically considered to have false-positive results and no subsequent complications developed. The last patient died on the day following the new result secondary to complications following surgery and renal failure.

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective study, we found that repeat sampling and testing within 48 h of a previous negative C. difficile EIA have a low diagnostic yield. A subsequent positive result was seen in 0.9% of cases when repeat tests were performed on the same day and 1.8% when tests were done on the next day. Similar low rates of result changes, 0.6% and 1.2%, respectively, were found when the potential bias from an earlier positive episode was excluded within a 3-month window. Additionally, when analyzing only the highly immunocompromised bone marrow transplant patients, the rates of a positive result following an initial negative result on the same or next day were comparable at 2.2% and 2.8%, respectively.

The direct fecal cytotoxicity test has historically been considered the gold standard diagnostic test for C. difficile, with a reported sensitivity of 60 to 100%. This method requires fibroblast cell culture and detects the cytotoxic effect produced by the presence of toxin B (2, 10). However, due to increased turnaround times, increased costs, and labor and facility requirements, most clinical laboratories no longer use this method. Currently, EIA or other rapid toxin-detecting methods are most commonly used, mostly due to their relative ease, decreased cost, and turnaround times as short as 2 h (1, 20, 26). However, several authors have raised serious questions about the sensitivity of standalone EIA testing.

In 2004, Snell et al. (22) demonstrated that using a two-step method in the diagnosis of C. difficile-associated diarrhea offered a marked increase in sensitivity compared to that of EIA alone. When using glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) EIA followed by a toxin detection immunoassay for positive cases, the sensitivity was over 96% and reached 100% when a tissue culture cytotoxin assay was used for GDH-positive, toxin-negative cases (22). Similar findings were observed in a study performed by Fenner et al. (9). Other groups urge the use of a two-step method, but instead of using a toxin EIA, a cell culture cytotoxicity neutralization assay was used (18, 23). All of these studies demonstrate a potential increase in sensitivity; however, there is a substantial increase in turnaround time and cost for potentially positive specimens detected by culture (4). Based on several of these studies, the IDSA and SHEA have suggested practice guidelines supporting the use of GDH screening plus a confirmatory assay for toxins A and B for the diagnosis of C. difficile infection (6).

Regardless of the true sensitivity of EIA, our observations suggest that repeat sampling and testing within 48 h have a low probability of yielding a clinically significant result. This low diagnostic yield was the same in all population groups, including the immunocompromised bone marrow transplant patients. In order to assess the outcome of the potential false-negative results, we reviewed the medical records of the 38 patients who converted to a positive result within 48 h. The clinical management was altered in 47% (18/38) of those patients (<0.6% of all tested patients); however, there were no reported complications or deaths attributable to the delayed diagnosis.

In our study, when EIA testing was repeated on days 2 to 3, an additional 8% of C. difficile-positive patients were detected, a value which was statistically significant (P < 0.00005). When using a two-step diagnostic approach, Snell et al. demonstrated an increase in sensitivity from 84.6% when using EIA alone to 96.1% when using the combined methods. This 12% increase in sensitivity detected an additional 14% of patients through the use of tissue culture cytotoxin assay (22). Our data suggest that repeating the EIA in a similar time frame also appears to increase the detection of C. difficile-positive patients, although not as much.

Based on the data and statistical analysis presented, our institution has instituted a new policy in which clinicians can submit specimens for “repeat C. difficile antigen test no more than every other day (approximately 48 h apart)” for an individual patient. Furthermore, our data confirmed the overtesting practiced by our physicians once a patient tests positive for the antigen. There is little to no value in repeating the EIA once a patient tests positive. The likelihood of a positive result is high, and neither a positive nor a negative result would change patient management since standard antibiotic treatment should last for 2 weeks. We used these data to support an addition to our new testing policy of prohibiting a repeat test within 1 week (7 days) of a positive result. Since the creation of this new toxin A/B EIA policy, our institution has reduced the number of tests per month by 50%, with a cost savings of over $40,000 per year.

In summary, there is not a perfect, simple, rapid test for the diagnosis of C. difficile-associated diarrhea. The use of a two-step algorithm appears to be promising; however, many institutions are currently using rapid toxin detection methods, such as EIA. Because of concern for their relatively low sensitivity, overutilization of these tests is likely to be widespread. We have shown that same-day or next-day repeat testing is not cost-effective. Our data provide a guideline for other institutions to utilize their data to develop similar utilization policies.

Acknowledgments

We specially thank Linda Pugh for the collection of the laboratory data set and Ben Staley for the collection of the pertinent pharmacy records.

Supported in part by the Department of Pathology, Immunology, and Laboratory Medicine at the University of Florida, College of Medicine.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 24 September 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aldeen, W. E., M. Bingham, A. Aiderzada, J. Kucera, S. Jense, and K. C. Carroll. 2000. Comparison of the TOX A/B test to a cell culture cytotoxicity assay for the detection of Clostridium difficile in stools. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 36211-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aslam, S., and D. M. Musher. 2006. An update on diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated disease. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 35315-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartlett, J. G. 2002. Clinical practice. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea. N. Engl. J. Med. 346334-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartlett, J. G., and D. N. Gerding. 2008. Clinical recognition and diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46(Suppl. 1)S12-S18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borek, A. P., D. Z. Aird, and K. C. Carroll. 2005. Frequency of sample submission for optimal utilization of the cell culture cytotoxicity assay for detection of Clostridium difficile toxin. J. Clin. Microbiol. 432994-2995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen, S. H., D. H. Gerding, S. Johnson, C. Kelly, V. Loo, L. C. McDonald, J. Pepin, and M. Wilcox. Clostridium difficile infection: clinical practice guidelines by SHEA and IDSA. Proceedings of the 45th Annual Meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, San Diego, CA. Infectious Diseases Society of America, Arlington, VA.

- 7.Fekety, R. 1997. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis. American College of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 92739-750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feldman, M., L. Friedman, and L. Brandt (ed.). 2006. Sleisenger and Fordtran's gastrointestinal and liver disease, p. 2393-2404. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA.

- 9.Fenner, L., A. F. Widmer, G. Goy, S. Rudin, and R. Frei. 2008. Rapid and reliable diagnostic algorithm for detection of Clostridium difficile. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46328-330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fordtran, J. S. 2006. Colitis due to Clostridium difficile toxins: underdiagnosed, highly virulent, and nosocomial. Proc. (Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent.) 193-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuijper, E. J., B. Coignard, and P. Tull. 2006. Emergence of Clostridium difficile-associated disease in North America and Europe. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 12(Suppl. 6)2-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lyerly, D. M., H. C. Krivan, and T. D. Wilkins. 1988. Clostridium difficile: its disease and toxins. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lyerly, D. M., N. M. Sullivan, and T. D. Wilkins. 1983. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for Clostridium difficile toxin A. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1772-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manabe, Y. C., J. M. Vinetz, R. D. Moore, C. Merz, P. Charache, and J. G. Bartlett. 1995. Clostridium difficile colitis: an efficient clinical approach to diagnosis. Ann. Intern. Med. 123835-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massey, V., D. B. Gregson, A. H. Chagla, M. Storey, M. A. John, and Z. Hussain. 2003. Clinical usefulness of components of the Triage immunoassay, enzyme immunoassay for toxins A and B, and cytotoxin B tissue culture assay for the diagnosis of Clostridium difficile diarrhea. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 11945-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohan, S. S., B. P. McDermott, S. Parchuri, and B. A. Cunha. 2006. Lack of value of repeat stool testing for Clostridium difficile toxin. Am. J. Med. 119356.e7-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owens, R. C., Jr., C. J. Donskey, R. P. Gaynes, V. G. Loo, and C. A. Muto. 2008. Antimicrobial-associated risk factors for Clostridium difficile infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46(Suppl. 1)S19-S31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reller, M. E., C. A. Lema, T. M. Perl, M. Cai, T. L. Ross, K. A. Speck, and K. C. Carroll. 2007. Yield of stool culture with isolate toxin testing versus a two-step algorithm including stool toxin testing for detection of toxigenic Clostridium difficile. J. Clin. Microbiol. 453601-3605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Renshaw, A. A., J. M. Stelling, and M. H. Doolittle. 1996. The lack of value of repeated Clostridium difficile cytotoxicity assays. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 12049-52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Russmann, H., K. Panthel, R. C. Bader, C. Schmitt, and R. Schaumann. 2007. Evaluation of three rapid assays for detection of Clostridium difficile toxin A and toxin B in stool specimens. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 26115-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samra, Z., A. Luzon, and J. Bishara. 2008. Evaluation of two rapid immunochromatography tests for the detection of Clostridium difficile toxins. Dig. Dis. Sci. 531876-1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snell, H., M. Ramos, S. Longo, M. John, and Z. Hussain. 2004. Performance of the TechLab C. DIFF CHEK-60 enzyme immunoassay (EIA) in combination with the C. difficile Tox A/B II EIA kit, the Triage C. difficile panel immunoassay, and a cytotoxin assay for diagnosis of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 424863-4865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ticehurst, J. R., D. Z. Aird, L. M. Dam, A. P. Borek, J. T. Hargrove, and K. C. Carroll. 2006. Effective detection of toxigenic Clostridium difficile by a two-step algorithm including tests for antigen and cytotoxin. J. Clin. Microbiol. 441145-1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turgeon, D. K., T. J. Novicki, J. Quick, L. Carlson, P. Miller, B. Ulness, A. Cent, R. Ashley, A. Larson, M. Coyle, A. P. Limaye, B. T. Cookson, and T. R. Fritsche. 2003. Six rapid tests for direct detection of Clostridium difficile and its toxins in fecal samples compared with the fibroblast cytotoxicity assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41667-670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Welch, D. F. 2006. Laboratory testing considerations for C. difficile disease. Proc. (Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent.) 1914-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilkins, T. D., and D. M. Lyerly. 2003. Clostridium difficile testing: after 20 years, still challenging. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41531-534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]