Abstract

Mesenchymal stromal/stem cells (MSCs) originally isolated from bone marrow (BM) have been derived from almost every tissue in the body. These multipotent cells can be differentiated in vitro and in vivo into various cell types of mesenchymal origin, such as bone, fat, and cartilage. Furthermore, under some experimental conditions these cells can differentiate into a wider variety of cell types. Upon systemic administration ex vivo expanded MSCs preferentially home to damaged tissues and participate in regeneration processes through their diverse biological properties. In vitro and in vivo data suggest that MSCs have low inherent immunogenicity and modulate/suppress immunological responses through interactions with different immune cells. Ease of isolation and ex vivo expansion of MSCs, combined with their intriguing differentiation and immunomodulatory potential, and their impressive record of safety in clinical trials make these cells prime candidates for cellular therapy. MSCs derived from BM are currently being evaluated for a wide range of clinical applications including for treatment of immune dysregulation disoders such as acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. In the future, MSCs might potentially provide novel therapeutic options for treatment/prevention of rejection and/or repair of organ allografts through their multifaceted properties.

Keywords: mesenchymal stromal cells, mesenchymal stem cells, solid organ transplanation, immunomodulation

1. Introduction

Bone marrow (BM) stromal cells were first described by Friedenstein and colleagues, who identified an adherent, fibroblast-like population in the adult BM capable of regenerating rudiments of bone in vivo (1). These cells were later shown to be capable of differentiating into other cells of mesenchymal lineage such as fat and cartilage. Additionally, it is believed these cells produce matrix elements of the stromal tissue to provide physical support, give rise to the cellular elements of hematopoietic microenvironmental niche, and secrete a variety of cytokines and growth factors to support HSC maintenance and differentiation in the BM (2, 3). Caplan was the first to use the term mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) (4) to reflect the multipotent capabilities of this population of BM resident cells and estimated that MSCs compromise 0.01% to 0.1% of total adult BM cells (5). However, three decades after their original description still there is no single definitive marker for their direct isolation from BM, and their exact anatomical location inside BM and true physiological role is not clear. It is also not clear if MSCs per se or some of their derivatives comprise the HSC cellular niche in BM. Based on recent data, osteoblasts (6, 7) which originate from MSCs, may play a major, although not exclusive (8), role as the true HSC niche.

MSCs are most commonly isolated by gradient centrifugation of BM aspirates to isolate mononuclear cells, followed by in vitro culture and serial passage. Although MSC preparations generated ex vivo appear homogenous under the light microscope, they probably compromise a heterogeneous group of progenitor cells, and on most occasions do not fulfill strict criteria for a stem-cell entity at a single cell level (i.e. self renewal and multilineage differentiation capacity). Thus, the term multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells (with the same acronym as MSCs) was recently proposed (9) as the preferred terminology. The criteria set forth for MSCs include adherence to plastic in standard culture conditions, and a combination of phenotypic and functional characteristics. Culture-expanded MSCs are considered to be negative for hematopoietic markers such as CD14, CD45, and CD34; although some strains of mice express CD34 antigen on a portion of their MSCs (10). On the other hand, MSCs are generally, but not homogeneously, positive for a number of cell surface molecules, including CD73 (SH3 or SH4), CD90, CD105 (SH2 or endoglin), CD44, CD29, and CD166. Finally, the biologic property that most uniquely identifies MSCs is their capacity for tri-lineage differentiation potential in vitro into bone, fat, and cartilage upon addition of proper exogenous growth factors (11). Further characterization of these cells has shown they possess a spectrum of matrix receptors and integrins, and secrete a variety of growth factors, chemokines, cytokines and extracellular matrix proteins (11, 12). However, the physiological correlation between ex vivo generated MSCs and their in vivo counterparts still remains unclear (13).

Despite the large amount of unknown information about MSC biology, MSCs have generated a lot of excitement in the field of regenerative medicine over the last decade. Enthusiasm about these cells was originally fueled by a flurry of studies suggesting MSCs not only differentiate into other types of cells of mesodermal lineage, but also into cells of endodermal and ectodermal lineages, including cardiomyocytes (14–16), endothelial cells (17), lung epithelial cells (18–21), hepatocytes (22–24), neurons (25–28), and pancreatic islets (29–32). Liechty et al. showed that intraperitoneal injection of adult human BM derived MSCs using an in utero sheep transplantation model results in engraftment in multiple organs with site-specific differentiation (33). However, this study did not show regeneration of different cell types by transplantation of MSCs at a single stem cell level. The presence of MSCs at injury sites and their presumed transdifferentiation potential provided a rationale for testing their use in a variety of injury models (12, 34, 35). Nevertheless, the degree of contribution to different tissues through trans-differentiation is now a matter of strong debate since many later studies could not duplicate the results of original reports on transdifferentiation potential of these cells (36–39). However, MSCs remain a very promising modality in cell therapy and continue to be tested in many different applications as new functional mechanisms for these cells are discovered.

While in the normal undisturbed host BM may be the preferred homing site for intravenously administered MSCs (40, 41), MSCs can be detected in low levels in numerous tissues following intravenous infusion (42, 43). Furthermore, in the presence of inflammation or injury MSCs may preferentially home to the inflammatory site (44, 45), probably via the SDF1/CXCR4 pathway (45–48). The combined ability of these cells to migrate to the site of injury/inflammation, stimulate proliferation and differentiation of resident progenitor cells, and promote recovery of injured cells through growth factor secretion and matrix remodeling keeps these cells in the forefront of regenerative medicine (49). Finally, exploitation of these cells in different clinical settings has been greatly facilitated by the emerging body of evidence that MSCs are immunoprivileged and, more importantly, possess immunosuppressive and other favorable immunomodulatory properties (50, 51).

Pluripotent MSCs have also been derived from BM using modifications in the culturing process and have been labeled with a variety of names such as multipotent adult progenitor cells (MAPCs) (52), marrow-isolated adult multilineage inducible cells (MIAMIs) (53), very small embryonic-like cells (VSEL) (54) and pre-mesenchymal stem cells (pre-MSC) (55) among others. These potentially more primitive types of MSCs require specific and stringent culture conditions such as prolonged culture duration at low cell density on matrix coated culture dishes, and use of certain types of medium incorporating pre-tested fetal calf serum and growth factors. Due to the complex nature of these isolation methodologies it is not known if such cells have any in vivo counterparts, especially in humans, or if they merely represent artefactual byproducts of the culture system. Thus, it is not clear if these MSC variants will reach the clinic anytime soon.

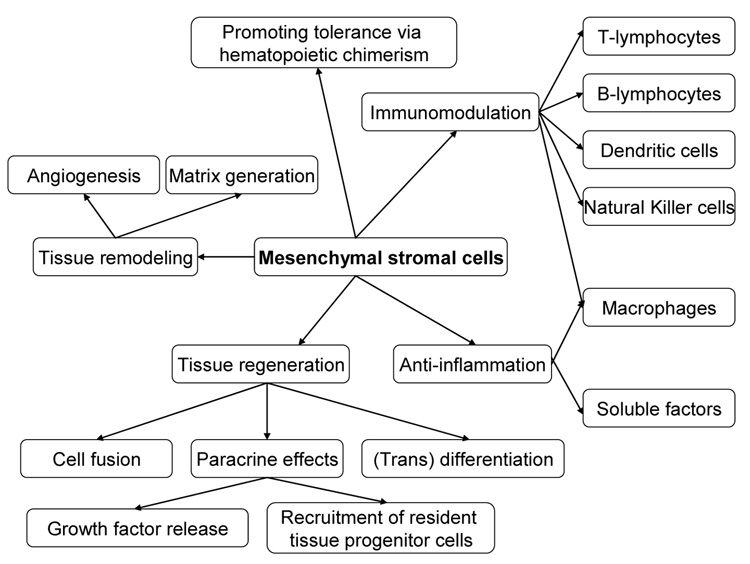

Although MSCs were originally isolated from BM, similar populations have been isolated from a wide variety of other adult tissues including, but not limited to, adipose tissue (56), skeletal muscle (57) synovium (58), and dental pulp (59); from neonatal tissues such as placenta (60), amniotic fluid (61), and umbilical cord blood (62); and from fetal lung, liver, and blood (63). It appears that MSCs essentially reside within connective tissue of most organs (64). Furthermore, many studies suggest that MSCs isolated from these diverse tissues possess similar biological characteristics, differentiation potential, and immunological properties (65–67). Although adipose tissue derived MSCs are reported to be an easily obtainable source of MSCs, and even have been used in a few small clinical trials (68–70), the bulk of the published literature concerns BM-derived MSCs as they are the best characterized and most advanced in clinical use. Additionally, their ease of generation in both autologous and allogeneic settings, extensive expansion capacity, and stable phenotype and function over many passages allows enough clinically usable MSCs to be generated from a small amount of BM aspirate over a period of several weeks. Thus, in this article we will focus primarily on the immunologic properties of BM-derived MSCs and their potentially beneficial effect in solid organ transplantation. However, other favorable characteristics of these cells including tissue remodeling/repair properties, growth factor release, angiogenesis, and nonspecific anti-inflammatory properties could all potentially play a role (Figure-1).

Figure-1.

Some of the proposed mechanisms for the potential beneficial effects of mesenchymal stromal cells in solid organ transplantation.

2. Immunomodulatory properties of MSCs

One of the most intriguing properties of ex vivo expanded MSCs is their ability to affect the immune response in vitro and in vivo. The emerging body of data indicates that MSCs derived from BM and other tissues modulate the immune system through interaction with a broad range of immune cells including T-lymphocytes, B-lymphocytes, natural killer cells, and dendritic cells (71–74). These immunomodulatory properties of MSCs have been the basis for their use in treating conditions characterized by immunological dysregulation such as Crohn’s disease and graft versus-host-disease (GVHD) after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transplantation. By extrapolation, the same immunomodulatory properties might be potentially useful for prevention or treatment for solid organ transplant rejection. However, there are many discrepancies and contradictions between reported immunological aspects of MSCs. These differences may be due to biological differences between MSCs isolated from different species or tissues, variables involved in culture conditions, or experimental methods.

Human MSCs express human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I on their cell surface but not HLA class II; however, Western blotting of cell lysates demonstrates intracellular HLA class II molecule expression (75). Treatment with interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), a pro-inflammatory cytokine known to increase cell surface expression of HLA molecules, increases expression of both cell surface HLA class I and class II molecules. Under normal conditions, the immune system will reject HLA-expressing allogeneic cells also expressing appropriate co-stimulatory molecules. Human MSCs do not express co-stimulatory molecules CD80, CD86, or CD40, even after IFN-γ stimulation. However, even transfection with CD80 and CD86 costimulatory molecules (76) or engagement of CD28 by anti-CD28 antibody (77) fail to allow human MSCs to induce proliferation of allogeneic lymphocytes in vitro in co-culture experiments.

2.1. MSCs and T-lymphocytes

T-lymphocytes are major executors of the adaptive immune response. A variety of in vitro studies on MSCs of human (77–79), nonhuman primate (80), and murine (81) origin have shown that MSCs possess the ability to suppress activation and proliferation of T-lymphocytes induced by both cellular and nonspecific mitogenic stimuli and have no immunological restriction (82). Similar suppression of T cell proliferation by MSCs is observed with cells that are either autologous or allogeneic to the responder cells in mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) assays. However, it has been suggested that at lower ratios MSCs might enhance proliferation of T-lymphocytes in MLR assays (75). Some studies have shown nonresponsiveness of T-lymphocytes in the presence of MSCs could be restored by removal of MSCs (78), while other studies variously indicated these cells induce anergy due to divisional arrest in T cells (83), induce T-cell tolerance (84), or induce regulatory T-lymphocytes to modulate immune responses. An increase in the population of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-lymphocytes was demonstrated in mitogen-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cell cultures in the presence of MSC (85). Despite this, Krampera et al. demonstrated presence of CD4+/CD25+ regulatory T-lymphocytes was not required for MSCs to inhibit T-lymphocyte proliferation (81).

Evidence for involvement of soluble factors in inhibition of proliferation of T-lymphocytes comes from transwell experiments in which MSCs and effector cells are separated by semi permeable membranes. Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGF-β), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and tryptophan catabolizing enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) have been reported to mediate suppression of T-lymphocyte proliferation; although occasionally these finding are contradictory to each other (86–88). It has also been suggested that suppressive factor(s) are not constitutively secreted by MSCs, but are secreted during MSCs co-culture with lymphocytes (89).

Although many have interpreted these in vitro data as indicating immunosuppression by MSCs, others have suggested that this presumed “immunosuppressive” property of MSCs might be a nonspecific result of a more general anti-proliferative effect of MSCs (73) and may be a property shared by all stromal cells (90). The relevance of these interactions observed in vitro to actual physiologic or pathologic conditions in vivo remains to be determined.

2.2. MSCs and B-lymphocytes

Although the mechanisms involved are not yet fully understood, both murine (91) and human studies (92) have shown that MSCs inhibit proliferation of B-lymphocytes stimulated by various methods. Intriguingly, based on Corcione et al. study, this inhibition is dose dependent; more MSCs lead to less inhibition. This contrasts with inhibition of T-cell proliferation, where more MSCs lead to greater inhibition of T-cell proliferation. Additionally, MSCs affect differentiation, antibody production, and chemotactic behavior of B cells (92). Transwell experiments again indicate that soluble factors released by MSCs play a major role in inhibiting proliferation of B cells (92).

2.3. MSCs and dendritic cells

Dendritic cells (DCs) constitute a heterogeneous population of professional, multiple lineage-derived antigen-presenting cells (APCs) from BM (93). Depending on their stages of cell development, activation and maturation, DCs have potential to induce both immunity and tolerance (94). MSCs interact with DCs at different levels of differentiation, maturation and function. MSCs inhibit differentiation of both CD14+ monocytes and CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors into DCs in a dose dependent fashion; and the differentiated DCs are less mature and exhibit less capability to stimulate allogeneic T-lymphocyte proliferation (95, 96). Studies have also shown that in the presence of MSCs, monocyte-derived DCs change from proinflammatory cytokine production to anti-inflammatory cytokine production (95, 97). Some transwell studies indicated MSCs suppression of DC differentiation might be partially mediated by soluble factors such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and Macrophage colony-stimulating factor (MCSF) (96), or even PGE2. Taken together, allogeneic MSCs may potentially induce a state of tolerance by modulating the generation, activation, and function of DCs.

2.4. MSCs and natural killer cells

Natural killer (NK) cells are a subset of lymphocytes participating in innate immunity, but having potential to coordinate sophisticated immune responses, and determine the outcome of adaptive immune responses (98, 99). Sotiropoulou demonstrated that at low NK:MSC ratios, MSCs alter NK cell phenotype and suppress proliferation, cytokine secretion, and cytotoxicity against HLA class I expressing targets (100). They concluded that some of these functions require cell-to-cell contact, whereas others are mediated by soluble factors, including TGF-β1 and PGE2. Still, although MSCs express HLA class I and should be protected against NK mediated killing, they were susceptible to lysis by activated NK cells, but not by freshly isolated NK cells. Spaggiari et al. showed that MSCs sharply inhibit IL-2-induced proliferation of resting NK cells; and they showed that IL-2-activated NK cells (but not by freshly isolated NK cells) efficiently lyse autologous and allogeneic MSCs. (101). In a more recent study, the same authors also showed that MSCs inhibit cytokine-induced proliferation of freshly isolated NK cells, and prevent their cytotoxic activity and cytokine production. They concluded that IDO and PGE2 represent key mediators of MSC-induced inhibition of NK cells(102).

2.5. MSCs as antigen presenting cells

Since many studies have shown that human MSCs are unable to induce proliferation of allogeneic lymphocytes in MLR assays, it is thought that MSCs are poor antigen presenting cells (APCs). However, Stagg et al. reported that mouse or human MSCs behave as a novel subset of nonhematopoietic conditional APCs, and provided experimental evidence that IFN-γ -treated MSCs process exogenous antigens and efficiently activate in vitro and in vivo antigen-specific immune responses (103). Chan et al. also demonstrated APC functions of MSCs to recall antigens Candida albicans and Tetanus toxoid (104). Furthermore, they showed major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) expression on MSCs requires autocrine stimulation by endogenous low level IFN-γ. In contrast to other studies, as levels of IFN-γ increased, MHC-II expression gradually decreased. Although the significance of reduced MHC-II expression was not addressed, the authors concluded MSCs may be able to change their functions from APCs to immune suppressor cells depending on their surrounding environment.

2.6. Immunological properties of MSCs in vivo

One of the first studies evaluating MSC function in vivo demonstrated systemic infusion of allogeneic BM-derived MSCs in baboons prolongs survival of skin allografts to 11 days compared to 7 days in control animals (80). Subsequently, the immunomodulatory effects of MSCs have been examined in a variety of animal models of organ and stem cell transplantation, autoimmunity, or tumor immunity. Nauta et al. studied the in vivo immunomodulatory properties of MSCs in a murine model of allogeneic BM transplantation in which sublethally irradiated recipients received allogeneic BM with or without host or donor MSCs (105). They showed addition of host MSCs significantly enhances long-term engraftment associated with tolerance to host and donor antigens, however, the infusion of donor MSCs is also associated with significantly increased rejection of allogeneic donor BM cells. They also showed injection of allogeneic donor MSCs alone in naive mice is sufficient to induce a memory T-cell response. Based on these results, the authors concluded allogeneic MSCs are not intrinsically immunoprivileged and under appropriate conditions allogeneic MSCs induce a memory T-cell response resulting in rejection of an allogeneic stem cell graft. Sudres at al verified MSCs suppress alloantigen-induced T cell proliferation in vitro in a dose-dependent manner. However, addition of MSCs to a BM transplant at a MSC:T-lymphocyte ratio providing strong inhibition of allogeneic responses in vitro, did not result in clinical improvement in incidence or severity of GVHD. This absence of clinical effect is not due to MSC rejection, because cells are detected in grafted animals (106). On the other hand, Yanez et al. showed infusion of ex-vivo expanded adipose tissue derived MSCs could control lethal GVHD in mice transplanted with haploidentical HSC (107). This study demonstrated only early and repeated infusions of MSCs are effective in controlling GVHD suggesting variations in dosage and timing of MSC infusion may explain contradictory results reported in other studies (106).

Another potential application for MSCs is amelioration of autoimmunity. Two studies showed MSCs could potentially ameliorate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in mice, a model of human multiple sclerosis, if given at the onset of disease but not if given after disease stabilization(84, 108). In contrast, infusion of MSCs did not have any beneficial effect in a murine model of rheumatoid arthritis(109).

In summary, although mechanisms underlying immunological properties of MSCS are still poorly understood, numerous studies have demonstrated MSCs are able to modulate function of different immune cells in vitro. However, some of these results are contradictory with animal model studies. This might be due to species differences, sources of MSCs or culture conditions used. Importantly, immunological characteristics of MSCs in vitro is usually examined in the context of interaction of ex vivo expanded MSCs with one or two populations of immune cells, a situation very different from in vivo in which cells interact with a much larger number of different cells in a dynamic and highly intricate manner. The true biological relevance of these cells and their interactions with immune system in vivo has yet to be shown.

3. Clinical experience with MSCs

Lazarus et al. were first to report a phase I trial to determine feasibility of collection, ex vivo culture-expansion, and intravenous infusion of human BM-derived MSCs (110). BM aspirates obtained from 23 patients with hematological malignancies in complete remission and autologous MSCs were culture expanded in vitro for 4–7 weeks. Fifteen of 23 patients underwent MSC infusion after ex vivo expansion. A BM examination two weeks later assessed histology and collected hematopoietic cells for in vitro culture. No adverse reactions were observed with infusion of these ex vivo expanded BM-derived MSCs. The same group subsequently conducted a phase I–II clinical trial to determine feasibility, safety, and hematopoietic effects of BM-derived, culture-expanded autologous MSCs infused into breast cancer patients in the course of high-dose chemotherapy and HSC rescue. Again, autologous MSCs were infused without any toxicity and hematopoietic recovery was rapid. However, since patients were also supported with large numbers of autologous peripheral blood CD34+ hematopoietic cells, MSCs’ role in enhancing hematopoietic recovery was uncertain (111). In a multicenter clinical trial, culture-expanded allogeneic MSCs derived from BM of HLA-identical sibling donors were infused 4 hours before infusion of HSCs in 46 patients undergoing myeloablative HSC transplantation for various hematological malignancies (112). There were no infusion-related toxicities, ectopic tissue formation, or increase in incidence or severity of GVHD. However, in comparison with historical controls, no acceleration of hematopoietic engraftment was observed. Nevertheless, these studies provided evidence that culture expansion of MSCs under good manufacturing practices (GMP) conditions is feasible and these cells are safe to infuse.

Recently, clinical interest has arisen in using the immunosuppressive capacities of MSCs to prevent/control GVHD after HSC transplantation. Le blanc et al. were the first to report the potential of MSC infusions for treatment of GVHD in a 9-year-old boy who received a matched unrelated donor HSC transplant for leukemia. The patient developed severe acute GVHD of the gut and liver that was unresponsive to all types of immunosuppression. Haploidentical MSCs were generated from the patient’s mother, not the original donor. After the infusion of one dose of MSCs, the GVHD disappeared. Infusion of a second dose of MSCs was also effective in treating GVHD when it recurred later. Importantly, after MSC infusion, lymphocytes from the patient continued to proliferate when co-cultured with maternally-derived lymphocytes, suggesting an immunosuppressive effect in vivo, but not development of tolerance. This was followed by a larger study in which MSCs were given to eight patients with steroid-refractory grades III–IV GVHD and one with extensive chronic GVHD. Two patients received MSC from HLA-identical siblings, six from haploidentical family donors, and four from unrelated mismatched donors. There were no acute side-effects after MSC infusions. Acute GVHD disappeared completely in six of eight patients, but two died soon after MSC treatment with no obvious response. Five patients were alive between 2 months and 3 years after transplantation (113). More recently, MSCs from haploidentical donors were co-transplanted with CD34+ cells from the same donors into 14 children. Compared to a graft failure rate of 15% in 47 historic controls, all patients given MSCs showed sustained hematopoietic engraftment without any adverse reaction; suggesting MSCs, possibly due to their potent immunosuppressive effect on alloreactive host T lymphocytes, could reduce risk of graft failure in haploidentical HSC transplant recipients (114). Currently, prospective randomized phase III studies in Europe and USA are in progress to further define the therapeutic potential of MSCs for promotion of HSC engraftment, and/or treatment/prevention of acute GVHD following allogeneic HSC transplantation (115). Despite all the encouraging results so far, clinical use of MSCs is still not a standardized and accepted form of cell therapy for treatment or prevention of GVHD.

Finally, culture expanded BM-derived MSCs have been used in several small phase I–II trials for a variety of non hematological indications including treatment of patients with metachromatic leukodystrophy and Hurler’s disease (116), osteogenesis imperfecta (117), myocardial infarction (118), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (119), and Crohn’s disease (120), among others (115). Amazingly, MSCs derived from other sources including fetal-derived MSCs have already reached the clinic (121).

4. Potential role of MSCs in solid organ transplantation

As early as 2000, it was suggested that immunomodulatory properties of MSCs could be exploited in solid organ transplantation for prevention and/or treatment of organ rejection (122). In contrast to most current pharmacological agents that target only a single pathophysiological pathway, MSCs potentially work through multiple mechanisms and have the potential to effect immunological, inflammatory, vascular, and regenerative pathways (123). Thus, harnessing both the immunosuppressive capabilities of MSC as a potential treatment for acute rejection following solid organ transplantation, and their ability for tissue repair provides an exciting opportunity for further research. Their ease of production combined with their apparent lack of need for HLA matching could also have significant implications for the therapeutic application of MSCs since previously expanded and cryopreserved MSCs derived from unrelated healthy donors can potentially be available for acutely ill patients in a timely manner. However, to date results reported with pre-clinical animal models have been conflicting and further research is urgently needed to clarify the utility of MSCs in solid organ transplantation.

4.1. MSCs and kidney

Acute and chronic kidney injuries post transplantation have a complex pathophysiology involving ischemic, inflammatory, and immunological mechanisms. Since in vitro and in vivo studies indicate MSCs might interfere with any of these arms, beneficial effects may arise through multiple mechanisms. In animal models, intravenously or locally injected syngeneic and/or allogeneic MSCs localize to the kidney and potentially improve organ function although the mechanism for improvement remains highly controversial. For example, Morigi at al suggested MSCs engraft in damaged kidneys and differentiate into tubular epithelial cells, thereby restoring renal structure and function in a cisplatin-induced renal injury model (124). In contrast, other investigators suggested MSC treatment is associated with improvement of renal function independent of differentiation into target cells, but rather through complex paracrine effects (125, 126). Although the ultimate role of BM-derived MSCs in regeneration of kidney tissue in different pathological conditions needs to be determined, theoretically, harnessing immunomodulatory capabilities of MSCs in prevention and/or treatment of acute rejection coupled with their potential to repair damaged kidney is an attractive possibility. So far there is no report on the effect of MSCs in an animal kidney transplant model. Given the highly successful nature of anti-rejection medications especially for short term survival of transplanted kidneys, demonstrating potential benefits of MSCs would require a randomized study involving thousands of patents. It is highly unlikely that such randomized clinical trials would be implemented any time soon. The complex nature of chronic renal allograft nephropathy makes it much less likely that MSCs could be harnessed in prevention/treatment of this complication.

4.2. MSCs and pancreas

MSCs derived from BM and other tissues have been shown to differentiate into cells with a pancreatic phenotype by several investigators (29–32). Although this issue remains highly controversial, several attempts have been made to use these cells therapeutically in animal diabetes models. Lee et al. observed that in human MSC-treated diabetic mice, there was an increase in pancreatic islets and beta cells producing mouse insulin, thus raising the possibility that human MSCs may be useful in enhancing insulin secretion by mechanisms other than trans-differentiation of MSCs into pancreatic islets (127). Whatever the mechanism, pancreas supporting activity of MSCs combined with their immunomodulatory properties might provide a boost to immunosuppressive regimens post islet transplantation. It should be noted that many studies reporting effectiveness of BM stem cells for diabetes control used BM HSCs, not MSCs (128–130).

Itakura et al. tested the potential of MSCs to induce hematopoietic chimerism and thus immune tolerance through BM transplantation in a rat allogeneic islet transplantation model (131). They showed co-infusion of MSCs with BM cells and pancreatic islets facilitates induction of stable mixed hematopoietic chimerism under a non-myleoablative conditioning regimen. Although the primary islet grafts were rejected, half of the animals developed stable mixed hematopoietic chimerism and donor specific immune tolerance as evidenced by engraftment of donor skin and second set of islet transplants, and rejection of third party skin grafts. Interestingly, they also showed that the intravenous route of administration of MSCs and BM cells did not result in chimerism, but the intraportal route did and that infusion of islets was necessary for induction of chimerism. Thus, promoting hematopoietic chimerism and tolerance toward transplanted solid organs might be potentially another role for MSCs in promoting solid organ transplantation.

4.3. MSCs and heart

Zhou et al. reported transplantation of Fisher344 rats with hearts from inbred Wistar rats followed by intravenous MSCs infusion at specific intervals modestly prolongs survival compared with controls.(132). However, Inoue et al. showed that while MSCs retain their immunosuppressive effect on MLR in vitro, their administration in a rat allogeneic heart transplant model not only does not prolong allograft heart survival, but tends to promote rejection (133). Also, Wu et al. demonstrated intravenously administered MSCs vigorously migrate to the allograft rejection site using a rat cardiac model; and these animals exhibit a significantly shortened graft survival time compared to animals receiving lactated Ringer’s solution without cells (134). Such discrepancies in the literature might be due to subtle differences in methodologies used. Further research in appropriate animal models especially large animal models is warranted before moving into clinical trials.

4.4. MSCs and lung

MSCs have been also tried for treatment of various lung injuries. Mei et al. used MSCs with and without pANGPT1-transfection in LPS-induced acute pulmonary inflammation in mice and showed improvement in alveolar inflammation (135). Ortiz et al. showed that murine MSCs home to the lung in response to bleomycin-induced injury, and reduce inflammation and collagen deposition in lung tissue (136, 137). Gupta et al. studied the direct intrapulmonary injection of MSCs 4 h after intrapulmonary administration of Escherichia coli endotoxin and showed MSCs increased survival compared with PBS-treated control mice. This beneficial effect of MSCs was independent of the ability of cells to engraft in the lung and was not related to clearance of endotoxin by MSCs (138). The potential of MSCs in reducing inflammation and fibrosis in the injured lung combined with their immunomodulatory properties might provide a rationale for testing in transplantation models.

4.5. MSCs and liver

Parekkadan recently reported that administration of MSC-derived molecules in two clinically relevant forms-intravenous bolus of conditioned medium (MSC-CM) or extracorporeal perfusion with a bioreactor containing MSCs (MSC-EB)-can provide a significant survival benefit in rats undergoing fulminant hepatic failure. Histopathological analysis of liver tissue after MSC-CM treatment showed dramatic reduction of panlobular leukocytic infiltrates, hepatocellular death and bile duct duplication. Furthermore, using computed tomography of adoptively transferred leukocytes they showed that MSC-CM functionally diverts immune cells from the injured organ indicating altered leukocyte migration by MSC-CM therapy may account for absence of immune cells in liver tissue (139). Such anti-inflammatory properties of MSCs might prove useful after liver transplantation, although again there is no preclinical data to support this hypothesis.

5. Safety concerns

Infusion of ex vivo expanded MSCs is considered relatively safe based on the general assumption these cells are hypoimmunogenic and elicit a suppressive effect on allogeneic lymphocyte responses. However, there is some evidence MSCs can potentially function as APCs and activate immune responses under appropriate conditions (103, 104). Indeed, some xenotransplantation studies with human MSCs in non-immunocompromised animals suggest MSCs are not intrinsically immunoprivileged (140). Recent studies also suggest that MSCs could become neoplastic after long-term culture (141–144). Furthermore, Djouad et al. demonstrated MSCs prevent rejection of allogeneic tumor cells in immunocompetent mice and promote tumor formation when injected locally or systemically (89). Karnoub et al. showed in a murine xenograft model that BM-derived human MSCs, when mixed with otherwise weakly metastatic human breast carcinoma cells and injected into a subcutaneous site, cause cancer cells to greatly increase their metastatic potency (145). Thus, although not seen in clinical trials, it is theoretically possible MSCs could promote tumor growth either through a direct effect on tumor growth or via immunosuppression of anti-tumor responses. It can be also argued that potential lack of immunoprivilege by allogeneic MSCs might be desirable. Administration of MSCs to exert an immunomodulatory/anti-inflammatory function might only temporarily suppress the immune system before their disappearance, reducing risks associated with prolonged immune suppression.

6. Future directions

Much of our knowledge of MSCs is based on in vitro experiments and much more research is needed to understand both the physiological role of these cells in vivo, and the mechanisms through which they mediate their apparent beneficial effects in regeneration, repair, and immunomodulation. Many of the perceived characteristics of MSCs might be artificially induced by in vitro culture and not have any in vivo counterpart However, this deficit should not deter their use if larger clinical trials validate their applicability, as therapeutic modalities are routinely used in clinical medicine without knowing the exact mechanism of action.

Nevertheless, there are several clinically important questions to be addressed: What are candidate indications for use of MSCs? What are the optimal dosing, timing, frequency, and routes of administration for different indications? How can production of MSCs be standardized? What is the role of additional immunosuppressive modalities combined with MSCs? Is it preferable to use autologous MSCs or allogeneic MSCs? What safety assays should be used to verify genetic stability of transplanted cells? Despite lack of apparent adverse effects seen in clinical trials to date, longer-term follow-up is also required given the immunosuppressive propertiesand tumor-growth promoting effects of MSCs, and potential for malignant transformation of transplanted cells,.

Finally, but not least important: What should be the role of MSCs in the field of solid organ transplantation since there is still no report on their use in solid organ transplant recipients? Since the currently available in vitro and in vivo data does not yet support use of MSCs in solid organ transplantation, these cells should first be screened in relevant pre-clinical and large animal models before testing their potential in repairing solid organ damage or preventing/ameliorating rejection.

6.1. Embryonic stem cell derived MSCs

We and others have reported generation of cells from BM with characteristics very similar to MSCs (146–149). Furthermore, ESC-derived MSCs also possess immunological properties very similar to BM-derived MSCs including expression of HLA-I but not HLA-II molecules, lack of immunogenicity when co-cultured with third party lymphocytes, and immunosuppression in MLR assays (in press). We propose co-transplantation of ESC-derived MSCs could provide protective immunomodulatory functions toward other cells/tissues derived from the same human ESC lines.

7. Conclusions

Today still, we know little about the exact anatomical location, tissue distribution, and functional role(s) of MSCs in vivo in health and disease conditions. However, these questions have not deterred clinicians from testing MSCs in several clinical applications. The original use of MSCs to accelerate hematopoietic engraftment after transplantation has now expanded to testing their potential to differentiate into and/or participate in tissue regeneration. More recently, their immunomodulatory properties are also being tested. However, mechanisms underlying possible in vivo immunomodulatory effects remain a critical and unresolved question. The potential role of MSCs to promote engraftment of tissues/organs and prevent/treat rejection may be multifactorial and might be dependent on secretion of soluble growth factors, increasing angiogenesis, suppressing alloreactive T cells, interacting with several arms of the immune system, and potentially cell fusion or even direct transdifferentiation. Preliminary clinical results are encouraging but there is no report yet on their potential in the setting of solid organ transplantation. It is important not to overestimate the potential therapeutic effects of MSCs given the nonrandomized nature of almost all the clinical studies reported so far.

Acknowledgement

I thank Dr. Laura H. Hogan for critical review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Friedenstein AJ, Petrakova KV, Kurolesova AI, Frolova GP. Heterotopic of bone marrow.Analysis of precursor cells for osteogenic and hematopoietic tissues. Transplantation. 1968;6(2):230–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dexter TM. Stromal cell associated haemopoiesis. J Cell Physiol Suppl. 1982;1:87–94. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041130414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tavassoli M, Friedenstein A. Hemopoietic stromal microenvironment. Am J Hematol. 1983;15(2):195–203. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830150211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells. J.Orthop.Res. 1991;9(5):641–650. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100090504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedenstein AJ, Chailakhjan RK, Lalykina KS. The development of fibroblast colonies in monolayer cultures of guinea-pig bone marrow and spleen cells. Cell Tissue Kinet. 1970;3(4):393–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.1970.tb00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calvi LM, Adams GB, Weibrecht KW, Weber JM, Olson DP, Knight MC, et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003;425(6960):841–846. doi: 10.1038/nature02040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J, Niu C, Ye L, Huang H, He X, Tong WG, et al. Identification of the haematopoietic stem cell niche and control of the niche size. Nature. 2003;425(6960):836–841. doi: 10.1038/nature02041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiel MJ, Morrison SJ. Maintaining hematopoietic stem cells in the vascular niche. Immunity. 2006;25(6):862–864. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dominici M, Le BK, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini F, Krause D, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8(4):315–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peister A, Mellad JA, Larson BL, Hall BM, Gibson LF, Prockop DJ. Adult stem cells from bone marrow (MSCs) isolated from different strains of inbred mice vary in surface epitopes, rates of proliferation, and differentiation potential. Blood. 2004;103(5):1662–1668. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284(5411):143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caplan AI. Adult mesenchymal stem cells for tissue engineering versus regenerative medicine. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213(2):341–347. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banfi A, Muraglia A, Dozin B, Mastrogiacomo M, Cancedda R, Quarto R. Proliferation kinetics and differentiation potential of ex vivo expanded human bone marrow stromal cells: Implications for their use in cell therapy. Exp Hematol. 2000;28(6):707–715. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(00)00160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makino S, Fukuda K, Miyoshi S, Konishi F, Kodama H, Pan J, et al. Cardiomyocytes can be generated from marrow stromal cells in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1999;103(5):697–705. doi: 10.1172/JCI5298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toma C, Pittenger MF, Cahill KS, Byrne BJ, Kessler PD. Human mesenchymal stem cells differentiate to a cardiomyocyte phenotype in the adult murine heart. Circulation. 2002;105(1):93–98. doi: 10.1161/hc0102.101442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cannon RO, 3rd, Dunbar CE. BM-derived cell therapies for cardiovascular disease. Cytotherapy. 2007;9(4):305–315. doi: 10.1080/14653240701431176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oswald J, Boxberger S, Jorgensen B, Feldmann S, Ehninger G, Bornhauser M, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells can be differentiated into endothelial cells in vitro. Stem Cells. 2004;22(3):377–384. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-3-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang G, Bunnell BA, Painter RG, Quiniones BC, Tom S, Lanson NA, Jr, et al. Adult stem cells from bone marrow stroma differentiate into airway epithelial cells: potential therapy for cystic fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(1):186–191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406266102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiss DJ, Berberich MA, Borok Z, Gail DB, Kolls JK, Penland C, et al. Adult stem cells, lung biology, and lung disease. NHLBI/Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Workshop. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3(3):193–207. doi: 10.1513/pats.200601-013MS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loi R, Beckett T, Goncz KK, Suratt BT, Weiss DJ. Limited restoration of cystic fibrosis lung epithelium in vivo with adult bone marrow-derived cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173(2):171–179. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200502-309OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spees JL, Olson SD, Ylostalo J, Lynch PJ, Smith J, Perry A, et al. Differentiation, cell fusion, and nuclear fusion during ex vivo repair of epithelium by human adult stem cells from bone marrow stroma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(5):2397–2402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437997100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz RE, Reyes M, Koodie L, Jiang Y, Blackstad M, Lund T, et al. Multipotent adult progenitor cells from bone marrow differentiate into functional hepatocyte-like cells. J Clin Invest. 2002;109(10):1291–1302. doi: 10.1172/JCI15182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sato Y, Araki H, Kato J, Nakamura K, Kawano Y, Kobune M, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells xenografted directly to rat liver are differentiated into human hepatocytes without fusion. Blood. 2005;106(2):756–763. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lange C, Bassler P, Lioznov MV, Bruns H, Kluth D, Zander AR, et al. Hepatocytic gene expression in cultured rat mesenchymal stem cells. Transplant Proc. 2005;37(1):276–279. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.11.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanchez-Ramos J, Song S, Cardozo-Pelaez F, Hazzi C, Stedeford T, Willing A, et al. Adult bone marrow stromal cells differentiate into neural cells in vitro. Exp Neurol. 2000;164(2):247–256. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woodbury D, Schwarz EJ, Prockop DJ, Black IB. Adult rat and human bone marrow stromal cells differentiate into neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2000;61(4):364–370. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20000815)61:4<364::AID-JNR2>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu P, Blesch A, Tuszynski MH. Induction of bone marrow stromal cells to neurons: differentiation, transdifferentiation, or artifact? J Neurosci Res. 2004;77(2):174–191. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munoz JR, Stoutenger BR, Robinson AP, Spees JL, Prockop DJ. Human stem/progenitor cells from bone marrow promote neurogenesis of endogenous neural stem cells in the hippocampus of mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(50):18171–18176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508945102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moriscot C, de Fraipont F, Richard MJ, Marchand M, Savatier P, Bosco D, et al. Human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells can express insulin and key transcription factors of the endocrine pancreas developmental pathway upon genetic and/or microenvironmental manipulation in vitro. Stem Cells. 2005;23(4):594–603. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davani B, Ikonomou L, Raaka BM, Geras-Raaka E, Morton RA, Marcus-Samuels B, et al. Human Islet-derived Precursor Cells Are Mesenchymal Stromal Cells that Differentiate and Mature to Hormone-expressing Cells In Vivo. Stem Cells. 2007 doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang DQ, Cao LZ, Burkhardt BR, Xia CQ, Litherland SA, Atkinson MA, et al. In vivo and in vitro characterization of insulin-producing cells obtained from murine bone marrow. Diabetes. 2004;53(7):1721–1732. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oh SH, Muzzonigro TM, Bae SH, LaPlante JM, Hatch HM, Petersen BE. Adult bone marrow-derived cells trans-differentiating into insulin-producing cells for the treatment of type I diabetes. Lab Invest. 2004;84(5):607–617. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liechty KW, MacKenzie TC, Shaaban AF, Radu A, Moseley AM, Deans R, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells engraft and demonstrate site-specific differentiation after in utero transplantation in sheep. Nat.Med. 2000;6(11):1282–1286. doi: 10.1038/81395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phinney DG, Prockop DJ. Concise review: mesenchymal stem/multipotent stromal cells: the state of transdifferentiation and modes of tissue repair--current views. Stem Cells. 2007;25(11):2896–2902. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chamberlain G, Fox J, Ashton B, Middleton J. Concise review: mesenchymal stem cells: their phenotype, differentiation capacity, immunological features, and potential for homing. Stem Cells. 2007;25(11):2739–2749. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keating A. Mesenchymal stromal cells. Curr Opin Hematol. 2006;13(6):419–425. doi: 10.1097/01.moh.0000245697.54887.6f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prockop DJ. "Stemness" does not explain the repair of many tissues by mesenchymal stem/multipotent stromal cells (MSCs) Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;82(3):241–243. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deans RJ, Moseley AB. Mesenchymal stem cells: biology and potential clinical uses. Exp Hematol. 2000;28(8):875–884. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(00)00482-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dazzi F, Horwood NJ. Potential of mesenchymal stem cell therapy. Curr Opin Oncol. 2007;19(6):650–655. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3282f0e116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Devine SM, Bartholomew AM, Mahmud N, Nelson M, Patil S, Hardy W, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells are capable of homing to the bone marrow of non-human primates following systemic infusion. Exp Hematol. 2001;29(2):244–255. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(00)00635-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wynn RF, Hart CA, Corradi-Perini C, O'Neill L, Evans CA, Wraith JE, et al. A small proportion of mesenchymal stem cells strongly expresses functionally active CXCR4 receptor capable of promoting migration to bone marrow. Blood. 2004;104(9):2643–2645. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao J, Dennis JE, Muzic RF, Lundberg M, Caplan AI. The dynamic in vivo distribution of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells after infusion. Cells Tissues Organs. 2001;169(1):12–20. doi: 10.1159/000047856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Devine SM, Cobbs C, Jennings M, Bartholomew A, Hoffman R. Mesenchymal stem cells distribute to a wide range of tissues following systemic infusion into nonhuman primates. Blood. 2003;101(8):2999–3001. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Francois S, Bensidhoum M, Mouiseddine M, Mazurier C, Allenet B, Semont A, et al. Local irradiation not only induces homing of human mesenchymal stem cells at exposed sites but promotes their widespread engraftment to multiple organs: a study of their quantitative distribution after irradiation damage. Stem Cells. 2006;24(4):1020–1029. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mouiseddine M, Francois S, Semont A, Sache A, Allenet B, Mathieu N, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells home specifically to radiation-injured tissues in a non-obese diabetes/severe combined immunodeficiency mouse model. Br J Radiol. 2007;80(Spec No 1):S49–S55. doi: 10.1259/bjr/25927054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chapel A, Bertho JM, Bensidhoum M, Fouillard L, Young RG, Frick J, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells home to injured tissues when co-infused with hematopoietic cells to treat a radiation-induced multi-organ failure syndrome. J Gene Med. 2003;5(12):1028–1038. doi: 10.1002/jgm.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shi M, Li J, Liao L, Chen B, Li B, Chen L, et al. Regulation of CXCR4 expression in human mesenchymal stem cells by cytokine treatment: role in homing efficiency in NOD/SCID mice. Haematologica. 2007;92(7):897–904. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dar A, Kollet O, Lapidot T. Mutual, reciprocal SDF-1/CXCR4 interactions between hematopoietic and bone marrow stromal cells regulate human stem cell migration and development in NOD/SCID chimeric mice. Exp Hematol. 2006;34(8):967–975. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uccelli A, Pistoia V, Moretta L. Mesenchymal stem cells: a new strategy for immunosuppression? Trends Immunol. 2007;28(5):219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Le Blanc K, Ringden O. Immunobiology of human mesenchymal stem cells and future use in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11(5):321–334. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prockop DJ, Olson SD. Clinical trials with adult stem/progenitor cells for tissue repair: let's not overlook some essential precautions. Blood. 2007;109(8):3147–3151. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-013433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jiang Y, Jahagirdar BN, Reinhardt RL, Schwartz RE, Keene CD, Ortiz-Gonzalez XR, et al. Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow. Nature. 2002;418(6893):41–49. doi: 10.1038/nature00870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.D'Ippolito G, Diabira S, Howard GA, Menei P, Roos BA, Schiller PC. Marrow-isolated adult multilineage inducible (MIAMI) cells, a unique population of postnatal young and old human cells with extensive expansion and differentiation potential. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 14):2971–2981. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kucia M, Reca R, Campbell FR, Zuba-Surma E, Majka M, Ratajczak J, et al. A population of very small embryonic-like (VSEL) CXCR4(+)SSEA-1(+)Oct-4+ stem cells identified in adult bone marrow. Leukemia. 2006;20(5):857–869. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anjos-Afonso F, Bonnet D. Nonhematopoietic/endothelial SSEA-1+ cells define the most primitive progenitors in the adult murine bone marrow mesenchymal compartment. Blood. 2007;109(3):1298–1306. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-030551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zuk PA, Zhu M, Mizuno H, Huang J, Futrell JW, Katz AJ, et al. Multilineage cells from human adipose tissue: implications for cell-based therapies. Tissue Eng. 2001;7(2):211–228. doi: 10.1089/107632701300062859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Williams JT, Southerland SS, Souza J, Calcutt AF, Cartledge RG. Cells isolated from adult human skeletal muscle capable of differentiating into multiple mesodermal phenotypes. Am Surg. 1999;65(1):22–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.De Bari C, Dell'Accio F, Tylzanowski P, Luyten FP. Multipotent mesenchymal stem cells from adult human synovial membrane. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(8):1928–1942. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200108)44:8<1928::AID-ART331>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gronthos S, Mankani M, Brahim J, Robey PG, Shi S. Postnatal human dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(25):13625–13630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240309797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.In 't Anker PS, Scherjon SA, Kleijburg-van der Keur C, de Groot-Swings GM, Claas FH, Fibbe WE, et al. Isolation of mesenchymal stem cells of fetal or maternal origin from human placenta. Stem Cells. 2004;22(7):1338–1345. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.In 't Anker PS, Scherjon SA, Kleijburg-van der Keur C, Noort WA, Claas FH, Willemze R, et al. Amniotic fluid as a novel source of mesenchymal stem cells for therapeutic transplantation. Blood. 2003;102(4):1548–1549. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bieback K, Kern S, Kluter H, Eichler H. Critical parameters for the isolation of mesenchymal stem cells from umbilical cord blood. Stem Cells. 2004;22(4):625–634. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-4-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.in 't Anker PS, Noort WA, Scherjon SA, Kleijburg-van der Keur C, Kruisselbrink AB, van Bezooijen RL, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells in human second-trimester bone marrow, liver, lung, and spleen exhibit a similar immunophenotype but a heterogeneous multilineage differentiation potential. Haematologica. 2003;88(8):845–852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Young HE, Mancini ML, Wright RP, Smith JC, Black AC, Jr, Reagan CR, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells reside within the connective tissues of many organs. Dev Dyn. 1995;202(2):137–144. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002020205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hoogduijn MJ, Crop MJ, Peeters AM, Van Osch GJ, Balk AH, Ijzermans JN, et al. Human heart, spleen, and perirenal fat-derived mesenchymal stem cells have immunomodulatory capacities. Stem Cells Dev. 2007;16(4):597–604. doi: 10.1089/scd.2006.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Puissant B, Barreau C, Bourin P, Clavel C, Corre J, Bousquet C, et al. Immunomodulatory effect of human adipose tissue-derived adult stem cells: comparison with bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Br J Haematol. 2005;129(1):118–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gotherstrom C, Ringden O, Westgren M, Tammik C, Le Blanc K. Immunomodulatory effects of human foetal liver-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;32(3):265–272. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fang B, Song Y, Lin Q, Zhang Y, Cao Y, Zhao RC, et al. Human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stromal cells as salvage therapy for treatment of severe refractory acute graft-vs.-host disease in two children. Pediatr Transplant. 2007;11(7):814–817. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2007.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fang B, Song Y, Zhao RC, Han Q, Lin Q. Using human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells as salvage therapy for hepatic graft-versus-host disease resembling acute hepatitis. Transplant Proc. 2007;39(5):1710–1713. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.02.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Garcia-Olmo D, Garcia-Arranz M, Herreros D, Pascual I, Peiro C, Rodriguez-Montes JA. A phase I clinical trial of the treatment of Crohn's fistula by adipose mesenchymal stem cell transplantation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(7):1416–1423. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stagg J, Galipeau J. Immune plasticity of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2007;180:45–66. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-68976-8_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Noel D, Djouad F, Bouffi C, Mrugala D, Jorgensen C. Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells and immune tolerance. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48(7):1283–1289. doi: 10.1080/10428190701361869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ramasamy R, Fazekasova H, Lam EW, Soeiro I, Lombardi G, Dazzi F. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit dendritic cell differentiation and function by preventing entry into the cell cycle. Transplantation. 2007;83(1):71–76. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000244572.24780.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nauta AJ, Fibbe WE. Immunomodulatory properties of mesenchymal stromal cells. Blood. 2007 doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-069716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Le Blanc K, Tammik C, Rosendahl K, Zetterberg E, Ringden O. HLA expression and immunologic properties of differentiated and undifferentiated mesenchymal stem cells. Exp.Hematol. 2003;31(10):890–896. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(03)00110-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Klyushnenkova E, Mosca JD, Zernetkina V, Majumdar MK, Beggs KJ, Simonetti DW, et al. T cell responses to allogeneic human mesenchymal stem cells: immunogenicity, tolerance, and suppression. J Biomed Sci. 2005;12(1):47–57. doi: 10.1007/s11373-004-8183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tse WT, Pendleton JD, Beyer WM, Egalka MC, Guinan EC. Suppression of allogeneic T-cell proliferation by human marrow stromal cells: implications in transplantation. Transplantation. 2003;75(3):389–397. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000045055.63901.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Di Nicola M, Carlo-Stella C, Magni M, Milanesi M, Longoni PD, Matteucci P, et al. Human bone marrow stromal cells suppress T-lymphocyte proliferation induced by cellular or nonspecific mitogenic stimuli. Blood. 2002;99(10):3838–3843. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Le Blanc K, Tammik L, Sundberg B, Haynesworth SE, Ringden O. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit and stimulate mixed lymphocyte cultures and mitogenic responses independently of the major histocompatibility complex. Scand J Immunol. 2003;57(1):11–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2003.01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bartholomew A, Sturgeon C, Siatskas M, Ferrer K, McIntosh K, Patil S, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells suppress lymphocyte proliferation in vitro and prolong skin graft survival in vivo. Exp Hematol. 2002;30(1):42–48. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(01)00769-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Krampera M, Glennie S, Dyson J, Scott D, Laylor R, Simpson E, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells inhibit the response of naive and memory antigen-specific T cells to their cognate peptide. Blood. 2003;101(9):3722–3729. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rasmusson I, Ringden O, Sundberg B, Le Blanc K. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit lymphocyte proliferation by mitogens and alloantigens by different mechanisms. Exp Cell Res. 2005;305(1):33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Glennie S, Soeiro I, Dyson PJ, Lam EW, Dazzi F. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells induce division arrest anergy of activated T cells. Blood. 2005;105(7):2821–2827. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zappia E, Casazza S, Pedemonte E, Benvenuto F, Bonanni I, Gerdoni E, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis inducing T-cell anergy. Blood. 2005;106(5):1755–1761. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Maccario R, Podesta M, Moretta A, Cometa A, Comoli P, Montagna D, et al. Interaction of human mesenchymal stem cells with cells involved in alloantigen-specific immune response favors the differentiation of CD4+ T-cell subsets expressing a regulatory/suppressive phenotype. Haematologica. 2005;90(4):516–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rasmusson I. Immune modulation by mesenchymal stem cells. Exp.Cell Res. 2006;312(12):2169–2179. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Aggarwal S, Pittenger MF. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate allogeneic immune cell responses. Blood. 2005;105(4):1815–1822. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Meisel R, Zibert A, Laryea M, Gobel U, Daubener W, Dilloo D. Human bone marrow stromal cells inhibit allogeneic T-cell responses by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-mediated tryptophan degradation. Blood. 2004;103(12):4619–4621. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Djouad F, Plence P, Bony C, Tropel P, Apparailly F, Sany J, et al. Immunosuppressive effect of mesenchymal stem cells favors tumor growth in allogeneic animals. Blood. 2003;102(10):3837–3844. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jones S, Horwood N, Cope A, Dazzi F. The antiproliferative effect of mesenchymal stem cells is a fundamental property shared by all stromal cells. J Immunol. 2007;179(5):2824–2831. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Augello A, Tasso R, Negrini SM, Amateis A, Indiveri F, Cancedda R, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal progenitor cells inhibit lymphocyte proliferation by activation of the programmed death 1 pathway. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35(5):1482–1490. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Corcione A, Benvenuto F, Ferretti E, Giunti D, Cappiello V, Cazzanti F, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate B-cell functions. Blood. 2006;107(1):367–372. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Steinman RM, Banchereau J. Taking dendritic cells into medicine. Nature. 2007;449(7161):419–426. doi: 10.1038/nature06175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Morelli AE, Thomson AW. Tolerogenic dendritic cells and the quest for transplant tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(8):610–621. doi: 10.1038/nri2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jiang XX, Zhang Y, Liu B, Zhang SX, Wu Y, Yu XD, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells inhibit differentiation and function of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Blood. 2005;105(10):4120–4126. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nauta AJ, Kruisselbrink AB, Lurvink E, Willemze R, Fibbe WE. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit generation and function of both CD34+-derived and monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2006;177(4):2080–2087. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Beyth S, Borovsky Z, Mevorach D, Liebergall M, Gazit Z, Aslan H, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells alter antigen-presenting cell maturation and induce T-cell unresponsiveness. Blood. 2005;105(5):2214–2219. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Huntington ND, Vosshenrich CA, Di Santo JP. Developmental pathways that generate natural-killer-cell diversity in mice and humans. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(9):703–714. doi: 10.1038/nri2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jukes JP, Wood KJ, Jones ND. Natural killer T cells: a bridge to tolerance or a pathway to rejection? Transplantation. 2007;84(6):679–681. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000280551.78156.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sotiropoulou PA, Perez SA, Gritzapis AD, Baxevanis CN, Papamichail M. Interactions between human mesenchymal stem cells and natural killer cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24(1):74–85. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Spaggiari GM, Capobianco A, Becchetti S, Mingari MC, Moretta L. Mesenchymal stem cell-natural killer cell interactions: evidence that activated NK cells are capable of killing MSCs, whereas MSCs can inhibit IL-2-induced NK-cell proliferation. Blood. 2006;107(4):1484–1490. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Spaggiari GM, Capobianco A, Abdelrazik H, Becchetti F, Mingari MC, Moretta L. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit natural killer cell proliferation, cytotoxicity and cytokine production: role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and prostaglandin E2. Blood. 2007 doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-074997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Stagg J, Pommey S, Eliopoulos N, Galipeau J. Interferon-gamma-stimulated marrow stromal cells: a new type of nonhematopoietic antigen-presenting cell. Blood. 2006;107(6):2570–2577. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chan JL, Tang KC, Patel AP, Bonilla LM, Pierobon N, Ponzio NM, et al. Antigen-presenting property of mesenchymal stem cells occurs during a narrow window at low levels of interferon-gamma. Blood. 2006;107(12):4817–4824. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-0057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nauta AJ, Westerhuis G, Kruisselbrink AB, Lurvink EG, Willemze R, Fibbe WE. Donor-derived mesenchymal stem cells are immunogenic in an allogeneic host and stimulate donor graft rejection in a nonmyeloablative setting. Blood. 2006;108(6):2114–2120. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-011650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sudres M, Norol F, Trenado A, Gregoire S, Charlotte F, Levacher B, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells suppress lymphocyte proliferation in vitro but fail to prevent graft-versus-host disease in mice. J Immunol. 2006;176(12):7761–7767. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yanez R, Lamana ML, Garcia-Castro J, Colmenero I, Ramirez M, Bueren JA. Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells have in vivo immunosuppressive properties applicable for the control of the graft-versus-host disease. Stem Cells. 2006;24(11):2582–2591. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zhang J, Li Y, Chen J, Cui Y, Lu M, Elias SB, et al. Human bone marrow stromal cell treatment improves neurological functional recovery in EAE mice. Exp Neurol. 2005;195(1):16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Djouad F, Fritz V, Apparailly F, Louis-Plence P, Bony C, Sany J, et al. Reversal of the immunosuppressive properties of mesenchymal stem cells by tumor necrosis factor alpha in collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(5):1595–1603. doi: 10.1002/art.21012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lazarus HM, Haynesworth SE, Gerson SL, Rosenthal NS, Caplan AI. Ex vivo expansion and subsequent infusion of human bone marrow-derived stromal progenitor cells (mesenchymal progenitor cells): implications for therapeutic use. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;16(4):557–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Koc ON, Gerson SL, Cooper BW, Dyhouse SM, Haynesworth SE, Caplan AI, et al. Rapid hematopoietic recovery after coinfusion of autologous-blood stem cells and culture-expanded marrow mesenchymal stem cells in advanced breast cancer patients receiving high-dose chemotherapy. J.Clin.Oncol. 2000;18(2):307–316. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.2.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lazarus HM, Koc ON, Devine SM, Curtin P, Maziarz RT, Holland HK, et al. Cotransplantation of HLA-identical sibling culture-expanded mesenchymal stem cells and hematopoietic stem cells in hematologic malignancy patients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11(5):389–398. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ringden O, Uzunel M, Rasmusson I, Remberger M, Sundberg B, Lonnies H, et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Treatment of Therapy-Resistant Graft-versus-Host Disease. Transplantation. 2006;81(10):1390–1397. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000214462.63943.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ball LM, Bernardo ME, Roelofs H, Lankester A, Cometa A, Egeler RM, et al. Cotransplantation of ex vivo expanded mesenchymal stem cells accelerates lymphocyte recovery and may reduce the risk of graft failure in haploidentical hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Blood. 2007;110(7):2764–2767. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-087056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Giordano A, Galderisi U, Marino IR. From the laboratory bench to the patient's bedside: An update on clinical trials with mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Physiol. 2007;211(1):27–35. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Koc ON, Day J, Nieder M, Gerson SL, Lazarus HM, Krivit W. Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell infusion for treatment of metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD) and Hurler syndrome (MPS-IH) Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;30(4):215–222. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Horwitz EM, Prockop DJ, Fitzpatrick LA, Koo WW, Gordon PL, Neel M, et al. Transplantability and therapeutic effects of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. Nat Med. 1999;5(3):309–313. doi: 10.1038/6529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Chen SL, Fang WW, Ye F, Liu YH, Qian J, Shan SJ, et al. Effect on left ventricular function of intracoronary transplantation of autologous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94(1):92–95. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Mazzini L, Mareschi K, Ferrero I, Vassallo E, Oliveri G, Boccaletti R, et al. Autologous mesenchymal stem cells: clinical applications in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurol Res. 2006;28(5):523–526. doi: 10.1179/016164106X116791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Taupin P. OTI-010 Osiris Therapeutics/JCR Pharmaceuticals. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2006;7(5):473–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Le Blanc K, Gotherstrom C, Ringden O, Hassan M, McMahon R, Horwitz E, et al. Fetal mesenchymal stem-cell engraftment in bone after in utero transplantation in a patient with severe osteogenesis imperfecta. Transplantation. 2005;79(11):1607–1614. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000159029.48678.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Devine SM, Hoffman R. Role of mesenchymal stem cells in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Curr Opin Hematol. 2000;7(6):358–363. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200011000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Brooke G, Cook M, Blair C, Han R, Heazlewood C, Jones B, et al. Therapeutic applications of mesenchymal stromal cells. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18(6):846–858. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Morigi M, Imberti B, Zoja C, Corna D, Tomasoni S, Abbate M, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells are renotropic, helping to repair the kidney and improve function in acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(7):1794–1804. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000128974.07460.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Togel F, Hu Z, Weiss K, Isaac J, Lange C, Westenfelder C. Administered mesenchymal stem cells protect against ischemic acute renal failure through differentiation-independent mechanisms. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289(1):F31–F42. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00007.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kunter U, Rong S, Djuric Z, Boor P, Muller-Newen G, Yu D, et al. Transplanted mesenchymal stem cells accelerate glomerular healing in experimental glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(8):2202–2212. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005080815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Lee RH, Seo MJ, Reger RL, Spees JL, Pulin AA, Olson SD, et al. Multipotent stromal cells from human marrow home to and promote repair of pancreatic islets and renal glomeruli in diabetic NOD/scid mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(46):17438–17443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608249103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Taira M, Inaba M, Takada K, Baba S, Fukui J, Ueda Y, et al. Treatment of streptozotocin-induced diabetes mellitus in rats by transplantation of islet cells from two major histocompatibility complex disparate rats in combination with intra bone marrow injection of allogeneic bone marrow cells. Transplantation. 2005;79(6):680–687. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000155500.17348.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ikebukuro K, Adachi Y, Suzuki Y, Iwasaki M, Nakano K, Koike Y, et al. Synergistic effects of injection of bone marrow cells into both portal vein and bone marrow on tolerance induction in transplantation of allogeneic pancreatic islets. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38(10):657–664. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Hess D, Li L, Martin M, Sakano S, Hill D, Strutt B, et al. Bone marrow-derived stem cells initiate pancreatic regeneration. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21(7):763–770. doi: 10.1038/nbt841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Itakura S, Asari S, Rawson J, Ito T, Todorov I, Liu CP, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells facilitate the induction of mixed hematopoietic chimerism and islet allograft tolerance without GVHD in the rat. Am J Transplant. 2007;7(2):336–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Zhou HP, Yi DH, Yu SQ, Sun GC, Cui Q, Zhu HL, et al. Administration of donor-derived mesenchymal stem cells can prolong the survival of rat cardiac allograft. Transplant Proc. 2006;38(9):3046–3051. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Inoue S, Popp FC, Koehl GE, Piso P, Schlitt HJ, Geissler EK, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of mesenchymal stem cells in a rat organ transplant model. Transplantation. 2006;81(11):1589–1595. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000209919.90630.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Wu GD, Nolta JA, Jin YS, Barr ML, Yu H, Starnes VA, et al. Migration of mesenchymal stem cells to heart allografts during chronic rejection. Transplantation. 2003;75(5):679–685. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000048488.35010.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Mei SH, McCarter SD, Deng Y, Parker CH, Liles WC, Stewart DJ. Prevention of LPS-induced acute lung injury in mice by mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing angiopoietin 1. PLoS Med. 2007;4(9):e269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Ortiz LA, Gambelli F, McBride C, Gaupp D, Baddoo M, Kaminski N, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell engraftment in lung is enhanced in response to bleomycin exposure and ameliorates its fibrotic effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(14):8407–8411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432929100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Ortiz LA, Dutreil M, Fattman C, Pandey AC, Torres G, Go K, et al. Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist mediates the antiinflammatory and antifibrotic effect of mesenchymal stem cells during lung injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(26):11002–11007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704421104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Gupta N, Su X, Popov B, Lee JW, Serikov V, Matthay MA. Intrapulmonary delivery of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells improves survival and attenuates endotoxin-induced acute lung injury in mice. J Immunol. 2007;179(3):1855–1863. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Parekkadan B, van Poll D, Suganuma K, Carter EA, Berthiaume F, Tilles AW, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived molecules reverse fulminant hepatic failure. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(9):e941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]