Abstract

Progesterone’s effects on hippocampal dependent behavior and synaptic connectivity maybe mediated through the progestin receptor (PR). Although estrogen induces PR mRNA and cytosolic PR in the hippocampus, nuclear PR immunoreactivity is undetectable by light microscopy, suggesting that PR is present at extranuclear sites. To determine whether this is the case, we used immunoelectron microscopy to examine PR distribution in the hippocampal formation of proestrus rats. Ultrastructural analysis revealed that PR labeling is present in extranuclear profiles throughout the CA1 and CA3 regions and dentate gyrus, and, in contrast to light microscopic findings, in nuclei of a few pyramidal and subgranular zone cells. Most neuronal PR labeling is extranuclear and is divided between pre- and post-synaptic compartments; approximately 30% of labeled profiles were axon terminals and 30% were dendrites and dendritic spines. In most laminae, except in CA3 stratum lucidum, about 15% of PR-immunoreactive profiles were unmyelinated axons. In stratum lucidum, where the mossy fiber axons course, more than 50% of PR labeled profiles were axonal. The remaining 25% of PR labeled profiles were glia, some resembling astrocytes. PR labeling is strongly dependent on estrogen priming as few PR labeled profiles were detected in ovariectomized, oil-replaced females. Synapses formed by PR-labeled terminals were predominantly asymmetric, consistent with a role for progesterone in directly regulating excitatory transmission. These findings suggest that some of progesterone’s actions in the hippocampal formation may be mediated by direct and rapid actions on extranuclear PRs and that PRs are well positioned to regulate progesterone-induced changes at synapses.

Keywords: estrogen-inducible progestin receptors, progesterone, extranuclear

INTRODUCTION

The ovarian steroid hormone progesterone has been implicated in a variety of functions in the brain, including cognition (Sandstrom and Williams, 2001), neuroprotection (Robertson et al., 2006; Stein, 2007), and dendritic remodeling (Woolley et al., 1990; Woolley and McEwen, 1993). In the hippocampal formation (HF) of female rats, progesterone counterbalances the effects of estrogen. While estrogen facilitates hippocampal-dependent learning, progesterone treatment after estrogen priming attenuates hippocampal-dependent performance (Sandstrom and Williams, 2001). Estrogen increases synaptic connectivity in females while progesterone decreases it in a receptor-dependent manner (Woolley and McEwen, 1993). Progesterone reduces incidence of epileptic activity both directly (Edwards et al., 2000) and through synthesis to allopregnanolone (Frye and Rhodes, 2005). In addition, progesterone has neuroprotective effects after traumatic or ischemic brain injury both alone and after estrogen priming (O’Connor et al., 2007; Sayeed et al., 2007; see review: Schumacher et al. 2007).

Understanding the actions of progesterone in the female HF has been hampered by the lack of readily detected nuclear progestin receptors (PRs) in this region. Although PR mRNA is present in the HF, no light microscopic reports to date have localized PR protein in specific hippocampal cell types or compartments (Guerra-Araiza et al. 2000; Camacho-Arroyo et al. 1998; Guerra-Araiza et al., 2002). Other steroid receptors, such as the alpha and beta isoforms of estrogen receptors, have extranuclear as well as nuclear locations in the HF that have been demonstrated by our laboratories using immunoelectron microscopy (Milner et al., 2005; Milner et al., 2001). The existence of extranuclear estrogen receptors, along with the ability of the PR antagonist RU486 to block progesterone’s effects on hippocampal plasticity (Woolley and McEwen, 1993) suggests the possibility that PRs may be present at extranuclear sites in the HF.

PR mRNA expression in the HF and other brain regions is increased during proestrus and with estrogen-replacement (Guerra-Araiza et al. 2000; Camacho-Arroyo et al. 1998; Guerra-Araiza et al., 2002). An estrogen-inducible PR protein has been detected in the HF of steroid-replaced rats by immunoblotting (Guerra-Araiza et al., 2003, Villamar-Cruz et al. 2006). In addition, estrogen-replacement increased PR binding in the CA subfield of the HF (Parsons et al., 1982). This suggested that anatomical identification of the PR protein likewise might be optimized during proestrus, the high-estrogen animals. Thus, to identify whether extranuclear PRs are present, and if so, to characterize their subcellular distribution, the present study used immunoelectron microscopy to examine PR in the HF of proestrus rats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Female adult Sprague-Dawley rats (225 – 250 grams and approximately 70 days old at time of arrival), from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) were obtained and were housed with 12:12-hr light/dark cycles with food and water available ad libitum. Estrous cycle stage was determined using vaginal smear cytology (Turner and Bagnara, 1971) and females were assessed for at least two full cycles. The proestrus (high estrogen) stage was examined in this study since high levels of gonadal steroids are known to produce maximal expression of nuclear PRs (Haywood et al., 1999). On the morning of proestrus as confirmed by vaginal smears, animals were sacrificed. Blood levels of estradiol were assessed by radioimmunoassay and found to be 10 pg/ml higher in proestrus animals than in diestrus animals collected at the same time. In addition, uterine weights were approximately 21% heavier in proestrus rats (0.8 ± 0.07 grams) versus diestrus (0.63 ± 0.04 grams). In a parallel study, female rats were ovariectomized and administered 10 μg estradiol benzoate (Sigma) in 100 μl sesame oil subcutaneously twice 24 hours apart and sacrificed 48 hours after the last treatment and a total of 7 days after ovariectomy. Control rats were injected with 100 μl sesame oil only. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Rockefeller University and Weill-Cornell Medical College Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

Immunocytochemistry

Antibodies

PR labeling was examined using three antibodies that recognize both the A and B isoforms of the human progestin receptor. A rabbit polyclonal antiserum to a peptide corresponding to amino acids 922-933 from Chemicon International (1:1000; Temucula, CA); a rabbit polyclonal antiserum to a peptide corresponding to amino acids 533-547 from Dako (1:500; Carpinteria, CA); and a rabbit polyclonal antiserum to a peptide corresponding to amino acids 412-526 from Lab Vision (1:1000; Fremont, CA). Due to the lack of detectable PR in the HF by light microscopy, PR labeling was confirmed in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus where intense nuclear labeling was detected with all three antibodies (Dako: Fig. 1B, Chemicon and Lab Vision not shown).

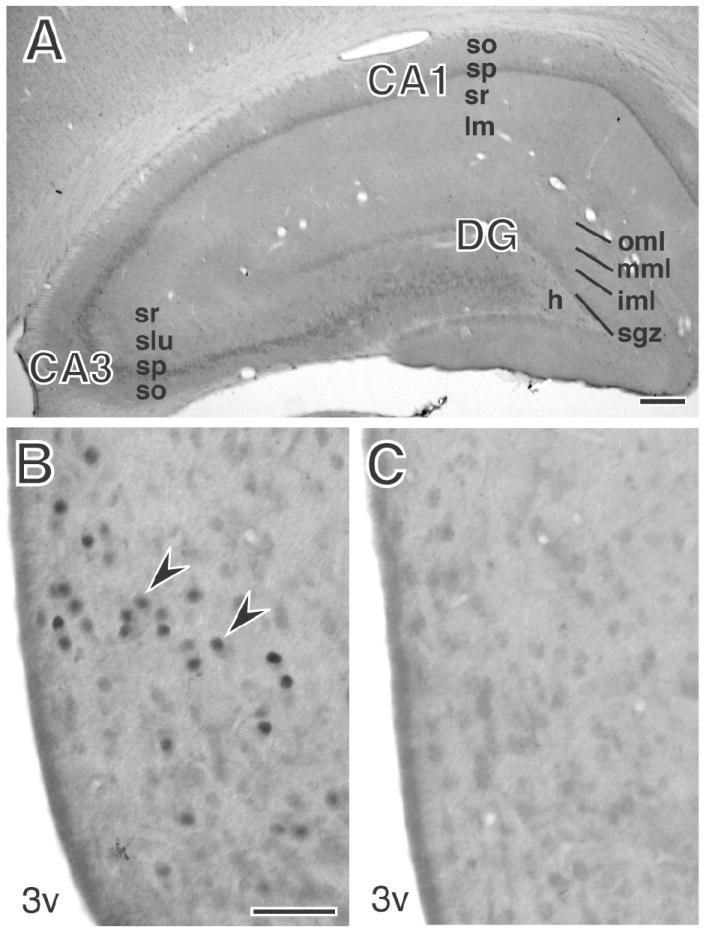

Figure 1. Immunohistochemical analysis of PR-ir labeling and antibody controls.

A: By light microscopy no PR-labeling was detected in the dorsal hippocampal formation. Hippocampal lamina examined by EM are indicated. B,C: The arcuate nucleus labeled for PR with the Dako antibody (B) or PR antibody preadsorbed with blocking peptide (C). PR labled nuclei are visible by light microscopy in the arcuate nucleus (arrows). Scale bar = 40 μm A. 200 μm B, C. DG, dentate gyrus; so, stratum oriens; sp, stratum pyramidale; sr, stratum radiatum; slm, stratum lacunosum-moleculare; slu, stratum lucidum; oml, mml, iml, outer, middle, and inner molecular layer; sgz, subgranular zone; h, hilus.

The specificity of the three antibodies has been previously described by immunoblot and immunohistochemistry. All three antibodies were generated to recognize both the A and the B isoforms of human PR. The Chemicon antibody recognizes PRA and PRB in estrogen-treated hypothalamic cell lines and rat uterus (Fitzpatrick et al., 1999). The Lab Vision antibody recognizes PRA and PRB in transfected cell lines and breast cancer cells (Hanekamp et al., 2004). The Dako antibody has been the most widely used for characterization of PR location and was used in this study for the semiquantitative counts of PR-immunoreactivity. Specificity of this antibody has been demonstrated by sucrose density gradients and absence of labeling in adsorption controls by immunoprecipitation methods (Traish and Wotiz, 1990), by preadsorption with the immunizing peptide (Traish and Wotiz, 1990; Haywood et al., 1999; Quadros et al., 2002; Quadros et al., 2007), and in thymus, uterus, and brain of PR knock-out mice (Kurita et al., 1998; Tibbetts et al., 1999; Quadros et al., 2007). As an additional control, the Dako antibody (1:500) was preadsorbed with 150 μg/ml of the immunizing peptide overnight at 4°C before incubating with the tissue. After preadsorption of the antibody, no nuclear PR immunoreactivity was detected in the arcuate nucleus by light microscopy (LM; Fig. 1C) and few PR immunoreactive (ir) profiles were detected in the HF by electron microscopy (EM; not shown).

Preparation of tissue

Rats were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (150 mg/kg, i.p.) and perfused through the ascending aorta sequentially with solutions of: 1) 10 -15 ml saline (0.9%) containing 1000 units of heparin; 2) 50 ml of 3.75% acrolein (Polysciences, Washington, PA) and 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M phosphate buffer (PB; pH 7.4); and 3) 200 ml of 2% paraformaldehyde in PB. Each brain was removed from the skull, cut into 5 mm coronal blocks and post-fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in PB for 30 min. Sections (40-μm-thick) through the HF were cut on a vibrating microtome (Leica, Wien, Austria) and collected into PB. Sections were stored in cryoprotectant (30% sucrose, 30% ethylene glycol in PB) at -20 C until immunocytochemical processing.

Pre-embedding Immunocytochemistry

Pre-embedding peroxidase immunocytochemistry was adapted (Milner et al., 2001) from Hsu et al. (1981). Briefly, sections were incubated in: (1) PB to remove cryoprotectant; (2) 1% sodium borohydride in PB, 30 min; (3); 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in Tris-saline solution (TS; 0.9% NaCl in 0.1 M Tris, pH 7.6) to block non-specific antibody binding, 30 min; (4) PR antiserum in 0.1% BSA/TS, 1 day at room temperature (~23 °C) followed by 4 days at 4°C; (5) 1:400 of anti-mouse or rabbit biotinylated-IgG, 30 min; (6) a 1:100 dilution of peroxidase-avidin complex (Vectastain Elite Kit), 30 min; and (7) 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) and H2O2 in TS, 6 min. All incubations were separated by washes in TS.

To more discretely localize PR, some sections were labeled using the immunogold procedure (Chan et al., 1990). For this, sections were processed through steps 1 through 4 described above except that the dilution of the PR primary antibody was 1:500. Sections then were incubated in goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin conjugated to 1 nm gold particles (1:50; Electron Microscopy Sciences (EMS), Fort Washington, PA) in 0.08% BSA and 0.01% gelatin in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) for 2 hours at room temperature. Sections were rinsed in PBS, post-fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 10 minutes, and rinsed in PBS followed by 0.2 M sodium citrate buffer (pH 7.4). The conjugated gold particles were enhanced by incubation in a silver solution (IntenSE; Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) for 5 - 7 minutes.

Sections for electron microscopy were fixed in 2% osmium tetroxide in PB and embedded in EMBed 812 (EMS) between two sheets of plastic (Chan et al., 1990). Sections through the area of interest were selected and glued on Epon chucks. Ultrathin sections (70 nm) from the Epon tissue interface of each section were cut on a Leica UTC ultramicrotome, collected on grids, and counterstained with uranyl acetate and Reynold’s lead citrate. Final preparations were viewed and analyzed on a Tecnai Biotwin electron microscope (FEI) equipped with an Advanced Microscopy Techniques digital camera (software version 3.2; Danvers, MA). To prepare photomicrographs for figures, levels, sharpness (using the unsharp mask), brightness and contrast were adjusted in Adobe Photoshop 7.0. Final figures were assembled in Quark Xpress 6.1.

Analysis of PR immunoreactivity

Electron microscopic examination of PR immunoreactivity was conducted on one block per area from one section per animal. Anatomically matched sections were chosen from each animal and at least 3 animals were analyzed for each hippocampal area. Thin sections were selected for analysis only if they were immediately adjacent to the tissue-plastic interface to reduce false-negatives due to differential penetration of markers (Sternberger, ed. 1986; Zaborszky et al., ed. 2006). For semi-quantitative counts, two 3025-μm2 grid squares were examined in fields from each lamina in the CA1 region, CA3 region and dentate gyrus from a mid-septotemporal level of the hippocampal formation (Swanson approximately level 32 (Swanson, 2000); AP -3.90 to -4.20 from Bregma). Only profiles with intact membranes were counted. All profiles containing PR-immunoreactivity were categorized according to the nomenclature outlined by Peters et al. (1991). PR labeled profiles were a) categorized by type (somata, dendrites, axons or glia); and b) qualitatively described in terms of the pattern of labeling, including association with subcellular locations (e.g., organelles, plasmalemma). PR labeled dendritic shafts were usually between 0.5 and 2 um in minimum diameter, contacted by terminals and sometimes gave rise to dendritic spines. Dendritic spines were usually small (<0.2 um in diameter) and contacted by terminals that formed asymmetric synapses. Unmyelinated axons were usually < 0.1 um and sometimes contained synaptic vesicles. Axon terminals were >0.1um in diameter, contained numerous vesicles and sometimes formed synaptic contacts. Synaptic contacts formed by terminals were classified as asymmetric or symmetric to provide morphological indications of the type of transmitter within the axon terminal (Carlin et al., 1980). Glial cell profiles were identified by their irregular shapes and thin processes; astrocytic profiles were identified further by the presence of filament bundles.

RESULTS

No PR immunoreactivity was detected in the HF by light microscopy (Fig. 1A). However, using EM, PR immunoreactivity was found in neurons and glia in all areas of the HF examined. Three antibodies were used to locate PR and all showed qualitatively similar staining patterns and immunoreactivity strength. The Dako antibody was used for further semiquantitative analysis. In preadsorption controls for the Dako antibody, no nuclear PR labeling was detected in the arcuate nucleus by light microscopy (Fig. 1B, C) and only 15 labeled profiles, including dendritic spines, axon terminals, and glia, were detected by EM in a 6050-μm2 area of CA1stratum radiatum. In comparison, 346 labeled profiles per 6050-μm2 were found in the CA1 stratum radiatum of non-preadsorbed tissue processed in parallel, confirming the ability of preadsorbing the antibody with the antigen to eliminate nearly all (about 96%) of the labeling for PR.

As an additional control, since PR expression in the HF has been shown to be dependent upon estrogen induction (Parsons et al., 1982; Guerra-Araiza et al., 2003), we examined PR-ir profiles in ovariectomized females that were injected with estradiol or oil. In animals that received oil, EM examination of PR-immunoreactivity revealed only 35 profiles (consisting of dendrites, axons and glia) per 6050-μm2 in the CA1 stratum radiatum. In animals that received estradiol, the number (207 profiles per 6050-μm2), and types (pre- and postsynaptic compartments and glia) of PR-labeled profiles were similar to those in the CA1 stratum radiatum of proestrus females. This finding suggests that the extranuclear PR detected in the HF is highly dependent on the presence of circulating estrogen.

The results of semiquantitative analysis showed that the relative distribution of PR-ir profiles varied between hippocampal region and within laminae of each region. PR-labeled profiles were present in all lamina of the three hippocampal regions examined, with the greatest numbers of PR-ir profiles observed in the neuropil in lamina lacking principal cells (Table 1, 2). In all regions, PR immunoreactivity was the most prevalent in axons and axon terminals (Table 1, 2).

Table 1.

Distribution of PR immunoreactive profiles in the principal cell layers of the Hippocampal Formation

| Cell layers | Dendrites | Soma | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axons | Terminals | shafts | spines | Glia | Unknown | Cytoplasm | Nuclei | |

| CA1 SP | 79 | 115 | 67 | 23 | 153 | 10 | 22 | 3 |

| CA3 SP | 96 | 69 | 41 | 16 | 105 | 12 | 39 | 0 |

| SGZ | 10 | 39 | 27 | 1 | 28 | 4 | 30 | 4 |

SP, stratum pyramidale; SGZ, subgranular zone

Table 2.

Distribution of PR immunoreactive profiles in the Hippocampal Formation1

| Hippocampal Subregion | Axons | Terminals | Dendritic shafts | Dendritic spines | Glia | Unknown |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA1 | ||||||

| st. oriens | 123 (14.14%) | 272 (31.26%) | 131 (15.06%) | 128 (14.71%) | 183 (21.03%) | 32 (3.68%) |

| st. radiatum | 200 (19.25%) | 359 (34.55%) | 142 (13.67%) | 156 (15.01%) | 156 (15.01%) | 25 (2.41%) |

| st. lacumole-moleculare | 180 (27.57%) | 150 (22.97%) | 147 (22.51%) | 42 (6.43%) | 114 (17.46%) | 19 (2.91%) |

| CA3 | ||||||

| st. oriens | 111 (12.83%) | 258 (29.83%) | 155 (17.92%) | 97 (11.21%) | 187 (21.62%) | 51 (5.90%) |

| st. radiatum | 491 (57.09%) | 142 (16.51%) | 88 (10.23%) | 17 (1.98%) | 101 (11.74%) | 14 (1.63%) |

| St. lucidum | 98 (14.26%) | 226 (32.90%) | 118 (17.18%) | 115 (16.74%) | 94 (13.68%) | 34 (4.95%) |

| DG | ||||||

| outer ml. | 85 (10.84%) | 204 (26.02%) | 180 (22.96%) | 90 (11.48%) | 193 (24.62%) | 30 (3.83%) |

| middle ml. | 77 (10.16%) | 159 (20.98%) | 190 (25.07%) | 108 (14.25%) | 196 (25.86%) | 28 (3.69%) |

| inner ml. | 86 (10.58%) | 205 (25.22%) | 181 (22.26%) | 102 (12.55%) | 202 (24.85%) | 34 (4.18%) |

| hilus | 149 (23.21%) | 179 (27.88%) | 79 (12.13%) | 78 (12.15%) | 113 (17.60%) | 41 (6.39%) |

| total | 1600 | 2154 | 1411 | 933 | 1539 | 308 |

A total of 6050 μm2 was examined from each lamina per block from three rats.

st., stratum; ml., molecular layer

Somata and dendrites contain PR immunoreactivity

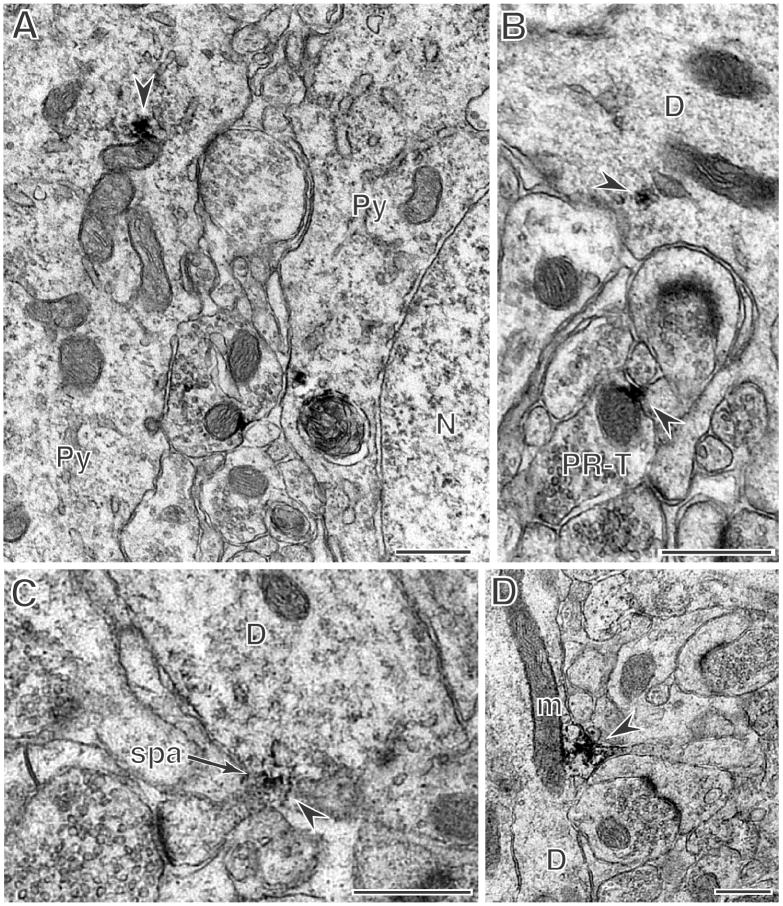

Most PR-peroxidase labeling was at extranuclear sites. However, although no nuclear labeling is detected at the light microscopic level, a few PR-labeled nuclei were found in the pyramidal cell layer of the CA1 and CA3 regions and in the subgranular zone of the DG (Table 1). No labeled nuclei were found in the granule cell layer. Within nuclei, PR-immunoperoxidase was sparse and located near the nuclear membrane or associated with heterochromatin (not shown). In comparison, relatively more PR immunoreactivity was found in the perikarya of pyramidal cells in the CA1 (Fig. 2A) and CA3 regions and in cells in the subgranular zone of the DG (Table 1). In the cytoplasm, patches of PR immunoreactivity were in close proximity to mitochondria and affiliated with endoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. PR immunoreactvity is in select somata, dendrites, and axons throughout the hippocampal formation.

A: PR-labeling (arrow) is found in the cytoplasm of a CA1 pyramidal cell (Py) but not the nucleus (N). B: In CA1 stratum radiatum, a dendrite (D) contains PR-labeling (arrow) near a saccule of endoplasmic reticulum. In the same field, an axon terminal (PR-T) contains peroxidase labeling (arrow) on a mitochondrion. (Chemicon antibody) C: Dendritic PR immunoreactivity is seen near the base of a dendritic spine (arrow) associated with a spine apparatus (spa) in the medial molecular layer of the dentate gyrus. D: In a dendrite in the CA3 stratum radiatum, peroxidase labeling is found near a mitochondrion (m) near the base of a dendritic spine (arrow). All micrographs show the Dako antibody unless otherwise indicated. Scale bars = 500 nm.

PR-labeled dendrites were identified throughout the hippocampal formation. In the CA1 and CA3, some PR-labeled dendrites clearly emanated from the somata of pyramidal cells. In the neuropil, patches of PR immunoreactivity were found in close proximity to elongated mitochondria in both dendrites and axons. Similar to the somata, patches of PR labeling were affiliated with mitochondria (Fig. 2B, D) although PR-ir particles were not present on the mitochondrial membrane when examined by immunogold (Fig. 3C). In addition, dendritic PR immunoreactivity was detected near mitochondria and the spine apparatus near the base of dendritic spines (Fig. 2C, D, 3C).

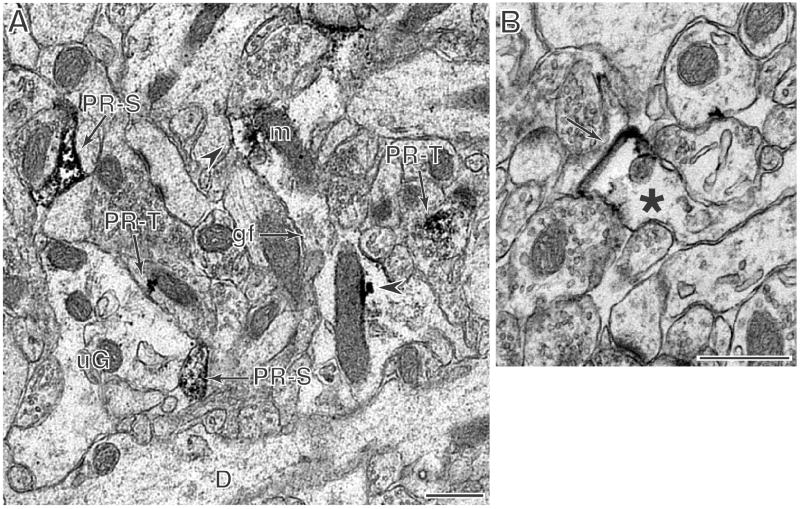

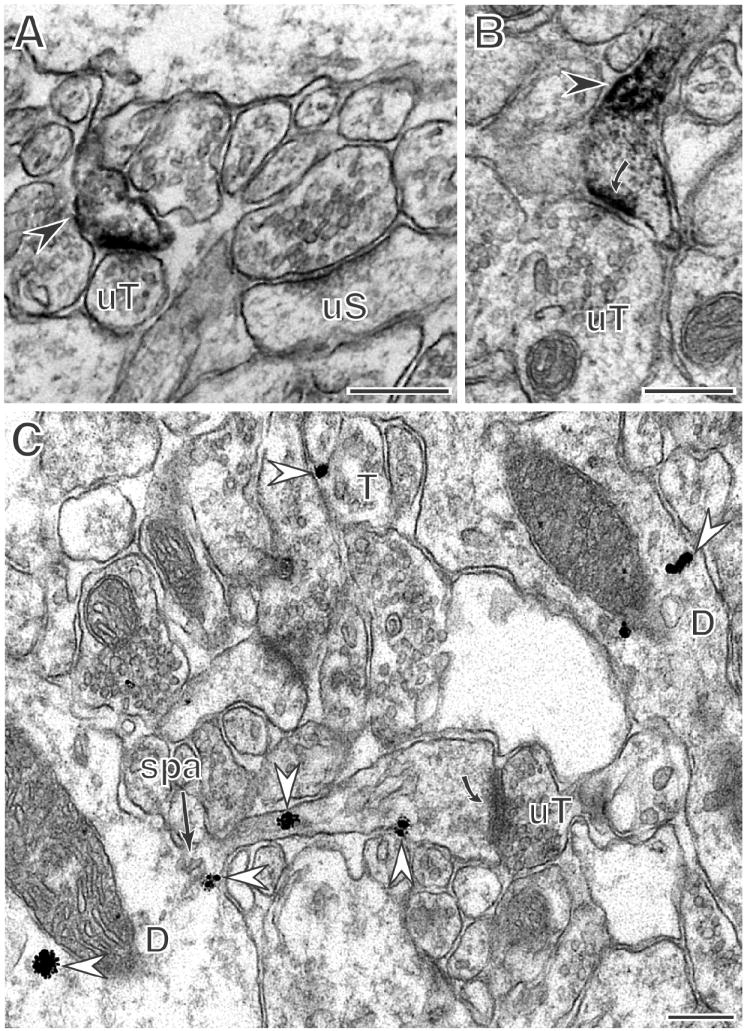

Figure 3. In all hippocampal subregions, PR immunoreactivity is in dendritic spines.

A: On the same dendrite (D) in the CA1 stratum radiatum, adjacent spines are unlabeled (uS) or labeled for PR (arrow). Both spines form synapses with unlabeled axon terminals (uT). (Lab Vision antibody) B: In the dentate gyrus inner molecular layer, PR peroxidase labeling is in the shaft of a dendritic spine (curved arrow) apposed to an unlabeled terminal (uT). C: In CA1 stratum radiatum, immunogold labeling for PR-ir (arrows) is found in the shaft and head of a dendritic spine, near the base of the spine associated with a spine apparatus (spa), and in dendrites where it is often in close proximity to mitochondria. All micrographs show the Dako antibody unless otherwise indicated. Scale bars = 500 nm.

Extranuclear PR is found in dendritic spines

Dendritic spines throughout the HF were labeled for PR. In some instances, dendritic spines were continuous with the shafts of large dendrites, some of which arose from pyramidal neurons. PR-immunoperoxidase labeling was affiliated with the postsynaptic density and surrounding membrane and within the cytoplasm of the spine head (Fig. 3A, B). With immunogold labeling, PR immunoreactivity was detected on the plasma membrane and in the cytoplasm of the spine head (Fig. 3C) but was not seen on the postsynaptic density. Using both immunoperoxidase and immunogold, PR-immunoreactivity within spines was affiliated with the spine apparatus (Figs. 2D, 3C). When the opposing terminals could be visualized, PR-ir spines were exclusively contacted by unlabeled axon terminals containing numerous small synaptic vesicles that formed asymmetric synapses (Fig. 3, 6A).

Figure 6. PR-ir labeling is in glial profiles.

A: In the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus, an astrocytic profile identified by the presence of glial filaments (gf) contains PR peroxidase labeling (arrowhead) adjacent to mitochondria (m) and contacts an unlabeled dendrite (D). An unlabeled astrocytic profile (ug) abuts the same dendrite and contacts two PR-labeled dendritic spines (PR-S, arrows) and a labeled axon terminal (PR-T, arrow). (Dako antibody) B: In CA1 stratum radiatum, a PR-labeled astrocytic profile (*) forms a gap junction with an unlabeled glial profile (arrow). (Lab vision antibody) Scale bars = 500 nm.

Semiquantitative analysis revealed that the proportion of PR-labeled profiles that were dendritic spines varied somewhat by region; however, in most of the neuropil, PR-ir spines accounted for ~15% of labeled profiles (Table 2). Two exceptions were seen: in the CA1 stratum lacunosum-moleculare 6% of PR-labeled profiles were spines and in the CA3 stratum lucidum only 1.5% of PR-labeled profiles were spines. In all areas examined, there was relatively more PR labeling in the dendritic shafts than in the spines emanating from dendrites (Table 2). Throughout the HF dendritic profiles labeled for PR amounted to ~20% of all labeled profiles.

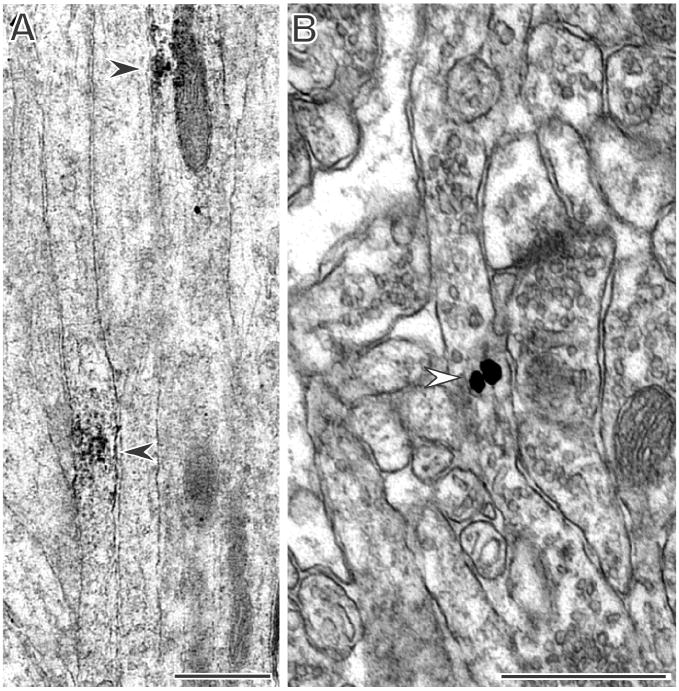

PR-ir axons are found in all hippocampal regions

Semiquantitative analysis of all lamina revealed that PR-labeled axons accounted for ~10% of all labeled profiles except in the CA3 stratum lucidum where PR-labeled axons made up 57% of all labeled profiles (Table 1). In the stratum lucidum of the CA3 region, PR-labeled axons were unmyelinated and appeared within the mossy fiber pathway (Fig. 4A). Unmyelinated PR-ir axons were also detected in the other lamina of the CA3 as well as in the CA1 and DG (Table 1, 2). Immunogold labeling revealed that PR-ir particles were found on synaptic vesicles within axons (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. PR immunoreactivity is in axons.

A: Clusters of PR peroxidase labeling (arrows) are found in axons in CA3 stratum lucidum. B: Immunogold labeling for PR is found on synaptic vesicles (arrow) in an axon in the CA1 stratum radiatum. Both A and B are labeled with the Dako antibody. Scale bars = 500 nm.

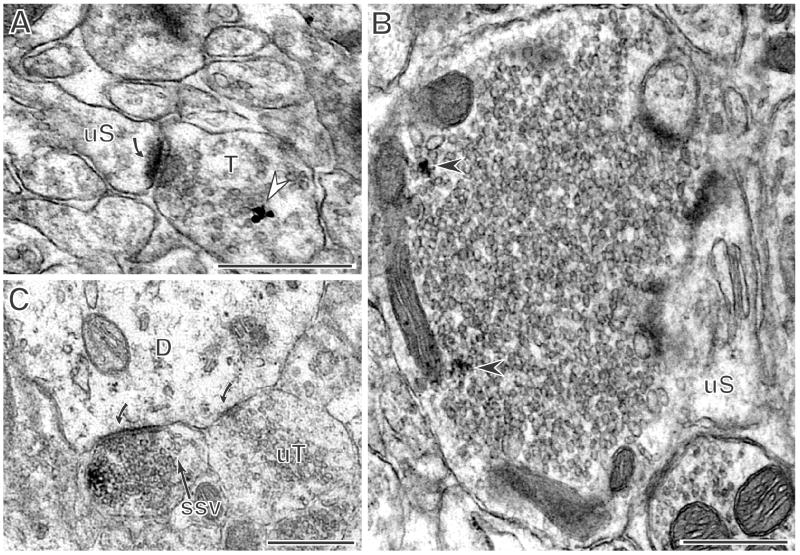

Extranuclear PR is found in axon terminals

In all regions PR labeled terminals comprised 20% to 30% of the labeled profiles (Table 1). Axon terminals with PR immunoreactivity contained numerous small synaptic vesicles and occasional dense core-vesicles. The majority of axon terminals ranged in size from 0.4-1.4 μm and had an average diameter of 0.8 μm. However, in the CA3 stratum lucidum, larger mossy fiber terminals also were labeled and ranged in size from 1.5 to 3 μm. In terminals, immunoperoxidase labeling had two types of distribution patterns. First, patches of PR immunoreactivity were associated with mitochondria (Fig. 2B, 5B, 6A), although these were not found on the mitochondrial membrane but rather were on endomembranes affiliated with mitochondria when examined by immunogold labeling (not shown). Second, PR immunoperoxidase product was associated with small synaptic vesicles (Fig. 5B, C, 6A). When visualized with immunogold, PR-ir particles were found over small synaptic vesicles (Fig 5A). Although PR immunoperoxidase labeling was sparse and thus appeared to be present at lower levels in axon terminals in comparison to dendritic spines, the presynaptic PR labeling was also discrete and consistently detected in sections from all animals. When visible, the majority of synaptic contacts formed by PR–ir terminals were of the asymmetric (excitatory) type and were made with unlabeled dendritic spines (Fig. 5A, B, 6A). The rare exceptions were in stratum radiatum of the CA3, where a few PR-ir terminals made symmetric synapses on the shafts of unlabeled dendrites (Fig. 5C) and in the CA1, where a small number of PR-ir terminals contacted PR-labeled pyramidal cells (not shown).

Figure 5. PR immunoreactivity is in axon terminals including mossy fiber terminals.

A: PR-immunogold labeling (arrow) is on synaptic vesicles in an axon terminal in CA1 stratum radiatum. B: A PR-labeled mossy fiber terminal (arrows) contacts an unlabeled spine (uS) in CA3 stratum lucidum. C: A PR-ir terminal (arrow) containing small synaptic vesicles (ssv) forms a symmetric synapse (curved arrow) with a dendrite in the CA3 stratum radiatum. An adjacent unlabeled terminal (uT) also forms a symmetric synapse (curved arrow) with the same dendrite. All micrographs labeled with the Dako antibody. Scale bars = 500 nm.

PR immunoreactivity is found in glial cells

PR labeling was found on glia processes throughout the HF. Depending on the hippocampal area and lamina between 10 – 25% of labeled profiles were identified as glia (Table 2). Most PR-ir glial processes were small and scattered throughout the neuropil. Most glial profiles also contained glial filaments, identifying them as originating from fibrous astrocytes (Fig. 6). In some instances, PR-labeled profiles formed gap junctions with other unlabeled astrocytic profiles (Fig. 6B). PR-immunoreactivity was apparent in the cytoplasm in close proximity to mitochondria and the cell wall but was not detected on these membranes when immunogold labeling for PR was used (not shown).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that PR immunoreactivity is found primarily in extranuclear portions of neurons and glia of the HF. This labeling coincides with the high levels of estradiol present in proestrus female rats, and along with data showing that estrogen treatment increases PR immunoreactivity, this suggests that virtually all of the labeling is dependent on prior estrogen priming. PR immunoreactivity was found in axons and axon terminals as well as dendrites and dendritic spines, with most of the last receiving excitatory inputs. Low levels of PR labeling were present in the nuclei of a few pyramidal neurons in the CA1 region and in a few cells in the subgranular zone. These findings support previous reports of hippocampal PR expression at the mRNA level while explaining the lack of detectable nuclear labeling at the light microscopic level.

Methodological Considerations

PR immunoreactivity was localized using three antibodies to different portions of the PR protein and all of which recognize both the A and B isoforms of the PR. All three antibodies labeled similar extranuclear sites when examined by EM. In addition, all three antibodies labeled nuclei in the arcuate nucleus. Since the Dako antibody is the most widely used for the study of PR immunoreactivity, this antibody was used to label sections for the semiquantitative analysis. Because PR-ir nuclei in the HF were detectable only by EM, their numbers were likely underestimated since previous studies have shown that larger profiles such as nuclei are more easily resolved by LM than by EM single-section analysis (Venkatesan et al., 1996). Furthermore, high levels of Triton are often useful to detect modest levels of nuclear immunoreactivity. Since Triton was not used for these studies, the infrequency of nuclear labeling may not be diagnostic of a complete absence of PR; rather the presence of sparse PR-labeling within nuclei may reflect the highly sensitive ability of immunoperoxidase to reveal low levels of expression. In contrast, small profiles (i.e. dendritic spines and axon terminals) are more easily resolved by EM; however, they also may be underestimated because the DAB reaction product for low abundance proteins may not fill the profile (Aoki et al., 2001). The subcellular distribution of PR-immunoreactivity was similar to, yet distinct from, that of other steroid receptors (Milner et al., 2001; Milner et al., 2005; Tabori et al., 2005).

Both the A and B isoforms of PR have been detected in the HF (Guerra-Araiza et al., 2003). These isoforms are highly homologous and are the product of a single gene. (Kastner et al., 1990; Giangrande et al., 1997; Giangrande and McDonnell, 1999;). As a result of the strong homology between PR-A and PR-B few distinctions have been made between the actions of each receptor. Since all three antibodies used in this study recognized both PR isoforms, the identification of any selectivity in isoform distribution must await further study.

Studies of neural PR binding suggest that there are two cytosolic PR pools in the brain: estrogen-sensitive and estrogen-insensitive (MacLusky and McEwen, 1978; MacLusky and McEwen, 1980). In HF, PR binding can be induced by estrogen in the CA1 region (Parsons et al., 1982), and whole-HF immunoblotting experiments have shown that the protein levels of both PR isoforms are up-regulated by estrogen and down-regulated by progesterone (Guerra-Araiza et al., 2003). In the present study, many PR-ir profiles were found throughout the HF in proestrus females and in estradiol-replaced ovariectomized females. In contrast, few PR-ir profiles were detected in the HF of ovariectomized and oil-replaced females. This suggests that levels of PR immunoreactivity in all fields of the HF may be regulated by estrogen. These findings are similar to our recent study of PRs at extranuclear sites in the rostral ventrolateral medulla during proestrus (Milner et al., 2007).

Nuclear and extranuclear PR is detected in principal cell layers

In addition to the nuclear labeling described above, PR labeling was detected by EM in perikarya of some pyramidal neurons and subgranular dentate cells, and in dendrites just emerging from somata. In addition, PR-labeled axons and axon terminals were found in the pyramidal cell layers. Together these locations suggest the possibility of modest progesterone regulation of somatic excitability directly at the cell body and through modulation of inputs to somata. Glia labeled for PR were also found interspersed in the cell layers, where they also may modulate neuronal excitability (Sul et al. 2004).

The cellular and subcellular distribution of PR immunoreactivity is most similar to previous reports for the beta form of the estrogen receptor (ERβ) (Milner et al., 2005). ERβ is primarily extranuclear and detected in somata, dendrites, dendritic spines, axons, and axon terminals of pyramidal cells and other neurons throughout the HF. ERβ is also detected within newly born neurons labeled with doublecortin in the subgranular zone of the DG and in astrocytes that form gap junctions (Herrick et al., 2006). Subcellularly, ERβ is also present near mitochondria and plasma membranes (Milner et al. JCN 2005). The alpha form of the estrogen receptor (ERα) is also found in axons and axon terminals, dendritic spines, and glia. However, in contrast to the expression patterns of ERβ and PR in the subcellular compartments of principal cells, interneurons in the HF have ERα labeled nuclei (Milner et al., 2001). The similarities in extranuclear ER and PR distribution are consistent with the possibility of colocalization at the level of individual spines. Although this cannot be established with the present data, such colocalization would provide an anatomical basis for highly compartmentalized interactions between ERs and PRs.

Classically, steroid receptors belong to the family of nuclear transcription factors that regulate gene expression. The discovery of extranuclear steroid receptors that can modulate rapid signaling to both alter protein activation and regulate gene expression led to the idea that nuclear and extranuclear receptor signals converge to generate changes in cell behavior (Hammes and Levine, 2007). Extranuclear ERs have been reported to have rapid non-genomic actions (Levin, 2005; Woolley, 2007). Similarly, PRs have been implicated in rapid progesterone-induced signaling in other steroid-sensitive tissues, including mammary, endometrial (Ballare et al., 2006), and prostate (Lange et al., 2007), suggesting that extranuclear PRs could have similar rapid actions in the HF. Our observation that PR is primarily extranuclear suggests that the reported effects of PR activation on synaptogenesis and neuroprotection (Woolley and McEwen, 1993) are mediated solely by signal transduction.

PR immunoreactivity is mostly in presynaptic cellular compartments

Extranuclear PR was found mostly in presynaptic sites throughout the neuropil. In axons and axon terminal PR immunoreactivity was found on small synaptic vesicles. Presynaptically, the putative association of PR with vesicles suggests that PR could be involved in vesicle loading or release, in effect modulating the strength of the synapse. PR could also be involved in synaptic scaling of excitatory inputs to postsynaptic neurons as well as in reversing estrogen-induced synaptogenesis and spinogenesis (Woolley and McEwen, 1993).

The majority of presynaptic PR-labeled profiles were terminals that formed asymmetric synapses on dendritic spines. This suggests that most of the PR-labeled terminals were glutamatergic afferents, particularly those arising from Schaffer-collateral or entorhinal pathways. The presence of PR in presumptive glutamatergic cells and projections suggests that progesterone–induced neuroprotection or spinogenesis could be a result of progesterone acting directly on cells to modulate excitability. Estrogen-induced spinogenesis has been demonstrated to depend on N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA)-type glutamatergic receptor activation (Woolley and McEwen, 1994). Reversal of estrogen’s effects on dendrites may be facilitated by progesterone regulation of intracellular Ca2+ signaling, since progesterone alone potentiated but in combination with estradiol attenuated glutamate-induced increases in [Ca2+] in primary hippocampal cultures (Nilsen and Brinton, 2002).

Some mossy fibers and granule cell axons also contained PR-immunoreactivity. In addition to glutamate, mossy fibers also contain opioid peptides and BDNF that are also known to fluctuate over the estrous cycle (see review Drake et al., 2007; Scharfman 2003). Moreover, we have recently found that in estrogen-treated ovariectomized animals progesterone further decreases enkephalin levels in the mossy fibers (Williams et al. SFN abstract). Progesterone may also blocking estrogen-induced opioid release in the medial preoptic nucleus as suggested by its ability to prevent estrogen-induced internalization of μ-opioid receptor (Sinchak and Micevych, 2001).

In rare instances, PR-labeled terminals formed symmetric synapses with CA1 pyramidal cell bodies and the dendrites of CA3 pyramidal cells. These observations suggest that PR is on a small minority of inhibitory afferents.

PR immunoreactivity is in postsynaptic cellular compartments

PR-labeling was found in dendritic shafts and spines, the majority of which are believed to originate in pyramidal cells. Dendritic spines mediate most glutamatergic excitatory inputs (Peters et al., 1991); changes in dendritic spine morphology are correlated with induction of long-term potentiation (LTP) (Yuste and Bonhoeffer, 2001). Estrogen enhances LTP magnitude, increases NMDA receptor transmission, as well as regulates NMDA receptor subunit expression and distribution within spines (Gazzaley et al., 1996; Woolley et al., 1997; Foy et al. 1999; Adams et al., 2004; Smith and McMahon, 2005; Smith and McMahon, 2006). During the estrous cycle, estrogen up-regulates dendritic spine synapse density in an NMDA receptor dependent manner (Woolley and McEwen, 1994) and progesterone rapidly down-regulates spine density. (Woolley and McEwen, 1993). Whether progesterone may modulate NMDA receptors prior to down-regulation of dendritic spines is not known; however, the present anatomical data are consistent with a direct role of PR in spine plasticity. PR labeling in dendrites is associated with the spine apparatus and mitochondria, suggesting that local regulation of synaptic protein expression and degradation could be under the control of progesterone-bound PR.

Cytoplasmic PR labeling was sometimes associated with endomembranes near mitochondria in dendrites, axons and axon terminals. Endoplasmic reticula associated with mitochondria are believed to regulate Ca2+ signals involved in synaptic and neuronal plasticity (Cammarata et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2004). The association of PR with endomembranes near mitochondria as well as the spine apparatus suggests that PR may have a role in Ca2+ sequesation. Activation of another steroid receptor, ERβ, has been reported to inhibit Ca2+ currents in the rostral ventrolateral medulla (Wang et al., 2006). Proximity to mitochondria also positions PR such that localized interactions between PR and cytoplasmic signaling molecules, particularly molecules that regulate the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway or oxidative stress (see review Schumacher et al., 2007), could contribute to progesterone-regulated neuroprotection. The effects of traumatic brain injury on mitochondrial respiration and cell loss have been reversed by low physiologic levels of progesterone in the CA1 and CA3 hippocampal regions and high physiologic levels increased cell survival in the CA3 region (Robertson et al., 2006)

Glial profiles contain PR immunoreactivity

PR-ir glial processes were found throughout the neuropil. Because microglia do not express mRNA for PR (Sierra, et al. 2008), the peroxidase labeling found here is believed to be present in astrocytes. PR mRNA and function has been described in astrocytes derived from rat forebrain (Jung-Testas et al. 1992) and cortex (Lacroix-Fralish et al., 2006). Astrocytes play a role in synaptic transmission, generate trophic factors and direct the development and maturation of individual synapses (Villoslada and Genain, 2004; Nishida and Okabe, 2007; Perea and Araque, 2007). Progesterone actions on glia in culture lead to production of agrin, further supporting a role for astrocytes and progesterone in synaptic remodeling (Tournell et al., 2006). In other brain areas, activation of glial PR has been reported to increase glial proliferation and promote myelination (Ghoumari et al., 2003; Ghoumari et al., 2005). For example, in the midbrain, estrogen-inducible PR may play a role in attenuating of the neuroinflammatory response by astrocytes to toxic stimuli (Kipp et al., 2007). Glial activation also contributes to the neuroprotective actions of ovarian steroids during spinal cord injury (De Nicola et al., 2006). Interestingly, glia cells are also capable of synthesizing neurosteroids, including progesterone, which can contribute to progesterone’s neuroprotective and organizational actions (Garcia-Segura and Melcangi, 2006). PR labeling was also found on gap junctions between astrocytic processes. Gap junctions provide direct access for exchange of chemical signals between adjacent cells. This type of steroid receptor localization has also been described by our laboratory for ERβ and the androgen receptor (Milner et al., 2005; Tabori et al., 2005).

Functional implications and Conclusions

Although many effects of progesterone are mediated through its metabolite allopregnanolone, which acts on GABAA receptors, a direct effect of progesterone via PRs is suggested by the ability of RU486 to block progesterone’s effects on hippocampal plasticity (Woolley and McEwen, 1993) and the present data demonstrating PRs at the sites implicated in progesterone’s physiological actions. In addition to plasticity, the presence of PRs at the same subcellular locations as estrogen receptors is consistent with a role for PRs in progesterone’s attenuation of estrogen-induced neuroprotection (Rosario et al., 2006). The frequency of PR-ir profiles in the animals in proestrus with high estrogen levels differs markedly from the low number of PR-ir profiles in the ovariectomized and oil-replaced animals. This suggests that the pool of extranuclear PR identified here is largely estrogen-inducible; however, this must be clarified in future studies.

PR immunoreactivity was found in pre- and postsynaptic sites throughout the hippocampus. The almost complete restriction of PR-labeled terminals to the excitatory-type morphology suggests a role for progesterone in the local regulation of synaptic plasticity. Modest PR immunoreactivity was present in neuronal nuclei in addition to the much more abundant labeling at extranuclear sites. These findings suggest that progesterone’s effects may be multipronged, involving direct and indirect genomic actions as well as rapid nongenomic actions, and targeting hippocampal neurons and glia.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Scott Herrick and Katherine Mitterling for technical assistance.

Grant sponsor: NIH grants NS007080 (B.S.M.), T32 DK07313 (B.S.M.; E.M.W.), DA08259 (T.A.M), HL18974 (T.A.M.) and minority postdoctoral supplement to DA08259 (A.T.-R.)

References

- Adams MM, Fink SF, Janssen WGM, Shah RA, Morrison HJ. Estrogen modulates synaptic N-Methyl-d-Asparatate receptor subunit distribution in the aged hippocampus. J Comp Neurol. 2004;474:419–426. doi: 10.1002/cne.20148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki C, Miko I, Oviedo H, Mikeladze-Dvali T, Alexandre L, Sweeney N, Bredt DS. Electron microscopic immunocytochemical detection of PSD-95, PSD-93, SAP-102, and SAP-97 at postsynaptic, presynaptic, and nonsynaptic sites of adult and neonatal rat visual cortex. Synapse. 2001;40(4):239–257. doi: 10.1002/syn.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballare C, Vallejo G, Vicent GP, Saragueta P, Beato M. Progesterone signaling in breast and endometrium. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;102(1-5):2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho-Arroyo I, Guerra-Araiza C, Cerbón MA. Progesterone receptor isoforms are differentially regulated by sex steroids in the rat forebrain. Neuroreport. 1998;9(18):3993–6. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199812210-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammarata PR, Chu S, Moor A, Wang Z, Yang SH, Simpkins JW. Subcellular distribution of native estrogen receptor alpha and beta subtypes in cultured human lens epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78:861–871. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2003.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlin RK, Grab DJ, Cohen RS, Siekevitz P. Isolation and characterization of postsynaptic densities from various brain regions: enrichment of different types of postsynaptic densities. J Cell Biol. 1980;86(3):831–845. doi: 10.1083/jcb.86.3.831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J, Aoki C, Pickel VM. Optimization of differential immunogold-silver and peroxidase labeling with maintenance of ultrastructure in brain sections before plastic embedding. J Neurosci Methods. 1990;33(2-3):113–127. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(90)90015-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Nicola AF, Gonzalez SL, Labombarda F, Deniselle MC, Garay L, Guennoun R, Schumacher M. Progesterone treatment of spinal cord injury: Effects on receptors, neurotrophins, and myelination. J Mol Neurosci. 2006;28(1):3–15. doi: 10.1385/jmn:28:1:3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djebaili M, Hoffman SW, Stein DG. Allopregnanolone and progesterone decrease cell death and cognitive deficits after a contusion of the rat pre-frontal cortex. Neuroscience. 2004;123(2):349–359. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake CT, Chavlin C, Milner TA. Opioid systems in the dentate gyrus. Prog Brain Res. 2007;163:245–63. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards HE, Epps T, Carlen PL, M NJ. Progestin receptors mediate progesterone suppression of epileptiform activity in tetanized hippocampal slices in vitro. Neuroscience. 2000;101(4):895–906. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00439-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick SL, Berrodin TJ, Jenkins SF, Sindoni DM, Deecher DC, Frail DE. Effect of estrogen agonists and antagonists on induction of progesterone receptor in a rat hypothalamic cell line. Endocrinology. 1999;140(9):3928–3937. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.9.7006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foy MR, Xu J, Xie X, Brinton RD, Thompson RF, Berger TW. 17beta-estradiol enhances NMDA recceptor-mediated EPSPs and long-term potentiation. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:925–929. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.2.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, Rhodes ME. Estrogen-priming can enhance progesterone’s anti-seizure effects in part by increasing hippocampal levels of allopregnanolone. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;81(4):907–916. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaley AH, Weiland NG, McEwen BS, Morrison JH. Differential regulation of NMDAR1 mRNA and protein by estradiol in the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1996;16(21):6830–6838. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-21-06830.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Segura LM, Melcangi RC. Steroids and Glial Cell Function. GLIA. 2006;54:485–498. doi: 10.1002/glia.20404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoumari AM, Dusart I, El-Etr M, Tronche F, Sotelo C, Schumacher M, Baulieu EE. Mifepristone (RU486) protects Purkinje cells from cell death in organotypic slice cultures of postnatal rat and mouse cerebellum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(13):7953–7958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1332667100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoumari AM, Wehrle R, Sotelo C, Dusart I. Bcl-2 protection of axotomized Purkinje cells in organotypic culture is age dependent and not associated with an enhancement of axonal regeneration. Prog Brain Res. 2005;148:37–44. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(04)48004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giangrande PH, McDonnell DP. The A and B isoforms of the human progesterone receptor: two functionally different transcription factors encoded by a single gene. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1999;54:291–313. discussion 313-294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giangrande PH, Pollio G, McDonnell DP. Mapping and characterization of the functional domains responsible for the differential activity of the A and B isoforms of the human progesterone receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(52):32889–32900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.32889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra-Araiza C, Cerbón MA, Morimoto S, Camacho-Arroyo I. Progesterone receptor isoforms expression pattern in the rat brain during the estrous cycle. Life Sci. 2000;66(18):1743–52. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00497-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra-Araiza C, Coyoy-Salgado A, Camacho-Arroyo I. Sex differences in the regulation of progesterone receptor isoforms expression in the rat brain. Brain Res Bull. 2002;59(2):105–9. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(02)00845-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra-Araiza C, Villamar-Cruz O, Gonzalez-Arenas A, Chavira R, Camacho-Arroyo I. Changes in progesterone receptor isoforms content in the rat brain during the oestrous cycle and after oestradiol and progesterone treatments. J Neuroendocrinol. 2003;15(10):984–990. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.01088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammes SR, Levin ER. Extranuclear steroid receptors: nature and actions. Endocrine Rev. 2007;28(7):726–741. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanekamp EE, Kuhne LM, Grootegoed JA, Burger CW, Blok LJ. Progesterone receptor A and B expression and progestagen treatment in growth and spread of endometrail cancer cells in nude mice. Endocriine-Related Cancer. 2004;11:831–841. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haywood SA, Simonian SX, van der Beek EM, Bicknell RJ, Herbison AE. Fluctuating estrogen and progesterone receptor expression in brainstem norepinephrine neurons through the rat estrous cycle. Endocrinology. 1999;140(7):3255–3263. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.7.6869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrick SP, Waters EM, Drake CT, McEwen BS, Milner TA. Extranuclear estrogen receptor beta immunoreactivity is on doublecortin-containing cells in the adult and neonatal rat dentate gyrus. Brain Res. 2006;1121(1):46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.08.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu SM, Raine L, Fanger H. Use of avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) in immunoperoxidase techniques: a comparison between ABC and unlabeled antibody (PAP) procedures. J Histochem Cytochem. 1981;29(4):577–580. doi: 10.1177/29.4.6166661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung-Testas I, Renoir M, Bugnard H, Greene GL, Baulieu EE. Demonstration of steroid hormone receptors and steroid action in primary cultures of rat glial cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1992;41(3-8):621–31. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(92)90394-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastner P, Krust A, Turcotte B, Stropp U, Tora L, Gronemeyer H, Chambon P. Two distinct estrogen-regulated promoters generate transcripts encoding the two functionally different human progesterone receptor forms A and B. Embo J. 1990;9(5):1603–1614. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08280.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipp M, Karakaya S, Johann S, Kampmann E, Mey J, Beyer C. Oestrogen and progesterone reduce lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-18 in midbrain astrocytes. J Neuroendocrinology. 2007;19(10):819–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2007.01588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurita T, Young P, Brody JR, Lydon JP, O’Malley BW, Cunha GR. Stromal progesterone receptors mediate the inhibitory effects of progesterone on estrogen-induced uterine epithelial cell deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis. Endocrinology. 1998;139(11):4708–4713. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.11.6317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange CA, Gioeli D, Hammes SR, Marker PC. Integration of rapid signaling events with steroid hormone receptor action in breast and prostate cancer. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:171–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.031905.160319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ER. Integration of the extranuclear and nuclear actions of estrogen. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19(8):1951–1959. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLusky NJ, McEwen BS. Oestrogen modulates progestin receptor concentrations in some rat brain regions but not in others. Nature. 1978;274(5668):276–278. doi: 10.1038/274276a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLusky NJ, McEwen BS. Progestin receptors in rat brain: distribution and properties of cytoplasmic progestin-binding sites. Endocrinology. 1980;106(1):192–202. doi: 10.1210/endo-106-1-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner TA, Mitterling K, Iadecola C, Waters EM. Ultrastructural localization of extranuclear progestin receptors relative to C1 neurons in the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Neurosci Letters. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.11.036. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner TA, Ayoola K, Drake CT, Herrick SP, Tabori NE, McEwen BS, Warrier S, Alves SE. Ultrastructural localization of estrogen receptor beta immunoreactivity in the rat hippocampal formation. J Comp Neurol. 2005;491(2):81–95. doi: 10.1002/cne.20724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner TA, McEwen BS, Hayashi S, Li CJ, Reagan LP, Alves SE. Ultrastructural evidence that hippocampal alpha estrogen receptors are located at extranuclear sites. J Comp Neurol. 2001;429(3):355–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen J, Brinton RD. Impact of progestins on estradiol potentiation of the glutamate calcium response. Neuroreport. 2002;13(6):825–830. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200205070-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida H, Okabe S. Direct astrocytic contacts regulate local maturation of dendritic spines. J Neurosci. 2007;27(2):331–340. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4466-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor CA, Cernak I, Johnson F, Vink R. Effects of progesterone on neurologic and morphologic outcome following diffuse traumatic brain injury in rats. Exp Neurol. 2007;205(1):145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons B, Rainbow TC, MacLusky NJ, McEwen BS. Progestin receptor levels in rat hypothalamic and limbic nuclei. J Neurosci. 1982;2(10):1446–1452. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-10-01446.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perea G, Araque A. Astrocytes potentiate transmitter release at single hippocampal synapses. Science. 2007;317(5841):1083–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1144640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Palay SL, Webster HD. The fine structure of the nervous system. New York: Oxford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Quadros PS, Pfau JL, Goldstein AY, De Vries GJ, Wagner CK. Sex differences in progesterone receptor expression: a potential mechanism for estradiol-mediated sexual differentiation. Endocrinology. 2002;143(10):3727–3739. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-211438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quadros PS, Pfau JL, Wagner CK. Distribution of progesterone receptor immunoreactivity in the fetal and neonatal rat forebrain. J Comp Neurol. 2007;504(1):42–56. doi: 10.1002/cne.21427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson CL, Puskar A, Hoffman GE, Murphy AZ, Saraswati M, Fiskum G. Physiologic progesterone reduces mitochondrial dysfunction and hippocampal cell loss after traumatic brain injury in female rats. Exp Neurol. 2006;197(1):235–243. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario ER, Ramsden M, Pike CJ. Progestins inhibit the neuroprotective effects of estrogen in rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 2006;1099(1):206–210. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.03.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandstrom NJ, Williams CL. Memory retention is modulated by acute estradiol and progesterone replacement. Behav Neurosci. 2001;115(2):384–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayeed I, Wali B, Stein DG. Progesterone inhibits ischemic brain injury in a rat model of permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2007;25(2):151–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfman HE, Mercurio TC, Goodman JH, Wilson MA, MacLusky NJ. Hippocampal excitability increases during the estrous cycle in the rat: a potential role for brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Neurosci. 2003;23(37):11641–52. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-37-11641.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher M, Guennoun R, Ghoumari A, Massaad C, Robert F, El-Etr M, Akwa Y, Rajkowski K, Baulieu EE. Novel perspectives for progesterone in hormone replacement therapy, with special reference to the nervous system. Endocrine Reviews. 2007;28(4):387–439. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra A, Gottfried-Blackmore A, Milner TA, McEwen BS, Bulloch K. Steroid Hormone Receptor Expression and Function in Microglia. GLIA. 2008 doi: 10.1002/glia.20644. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinchak K, Micevych PE. Progesterone blockade of estrogen activation of μ-opioid receptors regulates reproductive behavior. J Neurosci. 2001;21(15):5723–5729. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05723.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CC, McMahon LL. Estrogen-induced increase in the magnitude of long-term potentiation occurs only when the ratio of NMDA transmission to AMPA transmission is increased. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2650–2659. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0762-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CC, McMahon LL. Estrogen-induced increase in the magnitude of long-term potentiation is prevented by blocking NR2B-containing receptors. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8517–8522. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5279-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein DG. Progesterone exerts neuroprotective effects after brain injury. Brain Res Rev. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.06.012. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberger LA. Immunohistchemistry. New York, NY: Wiley; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Sul JY, Orosz G, Givens RS, Haydon PG. Astrocytic connectivity in the Hippocampus. Neuron Glia Biol. 2004;1(1):3–11. doi: 10.1017/s1740925x04000031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW. Brain Maps: Structure of the rat brain. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tabori NE, Stewart LS, Znamensky V, Romeo RD, Alves SE, McEwen BS, Milner TA. Ultrastructural evidence that androgen receptors are located at extranuclear sites in the rat hippocampal formation. Neuroscience. 2005;130(1):151–163. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibbetts TA, DeMayo F, Rich S, Conneely OM, O’Malley BW. Progesterone receptors in the thymus are required for thymic involution during pregnancy and for normal fertility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(21):12021–12026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tournell CE, Bergstrom RA, Ferreira A. Progesterone-induced agrin expression in astrocytes modulates glia-neuron interactions leading to synapse formation. Neuroscience. 2006;141(3):1327–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traish AM, Wotiz HH. Monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies to human progesterone receptor peptide-(533-547) recognize a specific site in unactivated (8S) and activated (4S) progesterone receptor and distinguish between intact and proteolyzed receptors. Endocrinology. 1990;127(3):1167–1175. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-3-1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CD, Bagnara JT. General Endocrinology. Philadelphia: W B Saunders; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesan C, Song XZ, Go CG, Kurose H, Aoki C. Cellular and subcellular distribution of alpha 2A-adrenergic receptors in the visual cortex of neonatal and adult rats. J Comp Neurol. 1996;365(1):79–95. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960129)365:1<79::AID-CNE7>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villamar-Cruz O, Manjarrez-Marmolejo J, Alvarado R, Camacho-Arroyo I. Regulation of the content of progesterone and estrogen receptors, and their cofactors SRC-1 and SMRT by the 26S proteasome in the rat brain during the estrous cycle. Brain Res Bull. 2006;69(3):276–81. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villoslada P, Genain CP. Role of nerve growth factor and other trophic factors in brain inflammation. Prog Brain Res. 2004;146:403–414. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(03)46025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Drake CT, Rozenblit M, Zhou P, Alves SE, Herrick SP, Hayashi S, Warrier S, Iadecola C, Milner TA. Evidence that estrogen directly and indirectly modulates C1 adrenergic bulbospinal neurons in the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Brain Research. 2006;1094:163–178. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.03.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams TJ, Torres-Reveron A, Gore AC, McEwen BS, Milner TA. Estrogen differentially affects leu-enkephalin and dynorphin immunoreactivity in the dorsal hippocampus of young, mature and old female rats. Annual Meeting Soc Neurosci 625.3 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS. Acute effects of estrogen on neuronal physiology. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:657–680. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS, Gould E, Frankfurt M, McEwen BS. Naturally occurring fluctuation in dendritic spine density on adult hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 1990;10(12):4035–4039. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-12-04035.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS, McEwen BS. Roles of estradiol and progesterone in regulation of hippocampal dendritic spine density during the estrous cycle in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1993;336(2):293–306. doi: 10.1002/cne.903360210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS, McEwen BS. Estradiol regulates hippocampal dendritic spine density via an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-dependent mechanism. J Neurosci. 1994;14(12):7680–7687. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-12-07680.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS, Weiland NG, McEwen BS, Schwartzkroin PA. Estradiol increases the sensitivity of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells to NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic input: correlation with dendritic spine density. J Neurosci. 1997;17(5):1848–1859. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-05-01848.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SH, Liu R, Perez EJ, Wen Y, Stevens SM, Jr, Valencia T, Brun-Zinkernagel AM, Prokai L, Will Y, Dykens J, Koulen P, Simpkins JW. Mitochondrial localization of estrogen receptor beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4130–4135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306948101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuste R, Bonhoeffer T. Morphological changes in dendritic spines associated with long-term synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:1071–1089. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaborszky L, Wouterlood FG, Lanciego JL, editors. Neuroanatomical Tract-Tracing 3: Molecules, Neurones, Systems. New York, NY: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]