Abstract

Growing research finds that reports of discrimination are associated with mental health. However, many US studies are focused on regional samples and do not control for important confounders such as other stressors and health conditions. The present study examines the association between self-reported racial discrimination and DSM-IV defined mental disorders among Asian respondents to the 2002–2003 US National Latino and Asian American Study (n=2,047).

Logistic regression analyses indicated that self-reported racial discrimination was associated with greater odds of having any DSM-IV disorder, depressive disorder, or anxiety disorder within the past 12 months -- controlling for sociodemographic characteristics, acculturative stress, family cohesion, poverty, self-rated health, chronic physical conditions, and social desirability. Further, multinomial logistic regression found that individuals who reported discrimination were at a twofold greater risk of having one disorder within the past 12 months, and a threefold greater risk of having two or more disorders.

Thus, self-reported discrimination was associated with increased risk of mental disorders among Asian Americans across the United States and this relationship was not explained by social desirability, physical health, other stressors, and sociodemographic factors. Should these associations ultimately be shown enduring and causal, they suggest that policies designed to reduce discrimination may help improve mental health.

Keywords: discrimination, Asian Americans, race, mental health, health disparities, USA

A hallmark report by the Surgeon General of the United States lists racial discrimination as a critical risk factor for mental disorders (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). However, while prior studies have laid an important foundation for the Surgeon General’s finding, it is difficult to know if the association between self-reported discrimination and mental disorders might be due to other factors such as a socially desirable response style and other stressors. In this study, we focus on the relationship between self-reported discrimination and mental disorders, controlling for potential confounders, among a nationally representative sample of Asian Americans (AAs). Our major hypothesis is that reports of discrimination will be associated with mental disorders after accounting for physical health conditions, other stressors, sociodemographic characteristics, and socially desirable responses.

Discrimination among Asian Americans

Discrimination can be defined as actions from individuals and institutions that negatively and systematically impact socially defined groups with less power (Jones, 2000). Asians have experienced a long history of discrimination within the U.S., including the exclusion of AAs from numerous rights, such as citizenship, suffrage, land ownership and due process under the law (Okihiro, 2001; Zia, 2000). Discrimination was institutionalized through Congressional actions (e.g. Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882), Presidential declarations (e.g. Executive Order 9066 interning Japanese Americans), and interpretations of the Supreme Court (e.g. United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind, ruling Asian Indians ineligible for citizenship in 1923). Many of these actions resulted from fears of a “yellow peril,” that hordes of unscrupulous and “unassimilable” persons would threaten the “American” way of life and economy (Chan, 1991).

More recent reports document that AAs experience hate crimes, racial profiling by police, and employment discrimination (Lai & Arguelles, 2003; Lien, 2002; Umemoto, 2000; Young & Takeuchi, 1998; U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, 1992). Although explicit racial prejudice has diminished over time (Bobo, 2000), a sizeable group of Americans voice negative sentiments about AAs. In 2001, one in four Americans agreed that Chinese Americans are “taking away too many jobs from Americans” and one in five Americans endorsed that Chinese Americans “don’t care what happens to anyone but their own kind” (Committee of 100, 2001). A national audit study in 2001 found that Asian American homebuyers encountered systematic discrimination in the housing market 21.5% of the time, a level similar to that of African Americans (Turner, Ross, Bednarz, Herbig, & Lee, 2003).

Discrimination and Mental Health

Reports of experiences with discrimination have been associated with several mental health indicators, including self-rated mental health status, self-esteem, happiness, depression, and generalized anxiety disorder among Blacks, Latinos and Whites (Finch, Kolody, & Vega, 2000; Kessler, Michelson, & Williams, 1999; Landrine & Klonoff, 1996; Schneider, Hitlan, & Radhakrishnan, 2000). Several studies have examined the association between perceived discrimination and mental health among Asian and Pacific Islanders worldwide, including Southeast Asian refugees and Koreans in Canada (Noh, Beiser, Kaspar, Hou, & Rummens, 1999; Noh & Kaspar, 2003); Vietnamese youth in Finland (Liebkind, 2004); South Asians and Chinese in the United Kingdom (Bhui, Stansfeld, Mckenzie, Karlsen, Nazroo, & Weich, 2005; Karlsen & Nazroo, 2002); and Pacific Islanders and Southeast Asians in New Zealand (Pernice & Brook, 1996).

Studies in the U.S. are also finding similar associations. Perceived discrimination was associated with depressive symptoms (Mossakowski, 2003) and substance use (Gee, Delva, & Takeuchi, in press) among Filipino Americans in Honolulu and San Francisco. Perceived discrimination was also associated with poor mental health (Gee, 2002) and decreased use of mental health services (Spencer & Chen, 2004) among Chinese Americans in Los Angeles. Rumbaut (1994) found that discrimination was associated with depressive symptoms among Filipino, Vietnamese, Laotian and Cambodian elementary school youth in San Diego. Yoshikawa, Wilson, Chae, and Cheung (2004) reported associations between discrimination and depressive symptoms among a convenience sample of gay AAs in a northeast city. Liang, Li, and Kim (2004), however, did not find associations between discrimination and mental health symptoms among AA students at a mid-Atlantic university. These studies have all focused on mental health symptoms, but have not examined if discrimination might also be associated with mental disorders. An investigation of disorders will aid clinicians and inform the allocation of resources.

How might discrimination influence mental disorders? Discrimination may lead to affective reactions (e.g. sadness) and shape one’s appraisal of their world (Harrell, 2000). Discrimination may also influence one’s self-concept by hindering their ability to control their environment, reinforcing secondary social status, and impacting self-esteem (Dubois, Burk-Braxton, Swenson, Trevendale, & Hardesty, 2002). Williams and Williams-Morris (2000) suggested that discrimination may assault victims’ ego identity and contribute to the internalization of negative stereotypes. Discrimination may also threaten one’s sense of control and foster hopelessness (Perlow, Danoff-Burg, Swenson, & Pulgiano, 2004). These factors in turn may lead to depression, anxiety and other mental disorders (Williams & Williams-Morris, 2000). Further, contemporary discrimination is more symbolic and covert than discrimination of the past (National Research Council, 2004). The subtle nature of current-day discrimination lends itself to ambiguity which may lead to rumination, a risk factor for depression (Harrell, 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema, Larson, & Grayson, 1999).

Discrimination may also act as a stressor (Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999; Harrel, 2000). Stressors are “conditions of threat, demands, or structural constraints that … question the operating integrity of the organism” (Wheaton, 1999, p.177). Illness may result when stressors exceed one’s ability to meet these demands (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Stressors associated with discrimination should be examined independent of other stressors (Harrell, 2000). However, most studies of discrimination often do not measure other stressors, leaving open whether discrimination proxies for other stressors rather than be an important factor per se (Williams, Neighbors, & Jackson, 2003).

To address this issue, we examine three other potential stressors: acculturative stress, low family cohesion, and poverty. Acculturative stress refers to the strains of adjustment among migrants, including the burdens of learning a new culture, worries about legal status, and potential guilt for leaving behind loved ones (Berry, Kim, Minde, & Mok, 1987). Acculturative stress has been associated with depression, anxiety and other health outcomes among Korean (Noh and Kaspar, 2003) and Latino immigrants (Finch & Vega, 2003; Hovey, 2000). Family cohesion denotes the emotional bonding between family members. Individuals from low cohesion families are often at higher risk for depression, suicidal ideation, anxiety and social avoidance (Harris & Molock, 2000; Reinherz, Paradis, Giaconia, Stashwick, & Fitzmaurice, 2003). Poor family functioning was associated with depression among Chinese Americans (Crane, Ngai, Larson, & Hafen, 2005). Discrimination was associated with parent-child conflict among Asian and other immigrant families, possibly because youths’ experiences with discrimination conflicted with their parents’ expectations of a meritocritous society (Rumbaut, 1994). Racial discrimination has been associated with lower socioeconomic position, including limited educational attainment, lower probability of employment and advancement, and depressed wages (Krieger, 1999; Williams, et al., 1997). Among AAs, reports of discrimination were associated with education and economic mobility (Goto, Gee, & Takeuchi, 2002; Cabezas, Tam, Lowe, Wong, & Turner, 1989). Socioeconomic position, in turn, is associated with mental disorders (Eaton & Muntaner, 1999). For example, the National Co-Morbidity Replication Survey found a threefold greater odds of major depression for people in poverty compared to those not in poverty (Kessler, et al., 2003).

In addition to these stressors, we consider physical illness as another potential stressor. Illnesses bring with them numerous demands, including worries about finances and prognosis, adherence to therapy, and potential life changes (Beverridge, Berg, Wiebe, & Palmer, 2006; Patterson & Garwick, 1994). Prior studies report that discrimination is associated with a variety of physical conditions, including high blood pressure, physical health conditions and poor self-rated health (Krieger & Sidney, 1996; Williams, et al., 2003). Physical health problems, in turn, may lead to mental health problems and vice versa (Creed, 1999; Roose, Glassman, & Seidman, 2001). Thus, physical health can be considered both an independent stressor as well as a potential consequence of discrimination.

An important consideration in studies of discrimination and mental disorders are potential response factors. One such factor is socially desirable reporting, the tendency for individuals to answer surveys in ways to make them “look good” and avoid looking “bad” (Paulhus, 1991). Social desirability is associated with increased responsiveness to social influence, avoidance of evaluation by others, and minimization of conflict (Kiecolt & McGrath, 1979; Paulhus, 1991). Among Asians, social desirability may be related to “saving face,” whereby individuals tend to understate problems to prevent shaming their families. (Gong, Gage, & Takada, 2003; Zane & Yeh, 2002). Social desirability has been associated with lower reporting of discrimination and may bias the association between self-reported discrimination and health (Krieger, Smith, Naishadham, Hartman, & Barbeau, 2005).

Hence, our study examines whether self-reported discrimination is associated with increased risk of mental disorders after controlling for a variety of potential stressors, socially desirable reporting, and sociodemographic characteristics.

Methods

Sample

The data come from the US National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS), a household survey conducted between 2002 and 2003. The current analyses focus on the Asian respondents. Three components comprise the sampling design: (1) core sampling of primary sampling units (metropolitan statistical areas and counties) and secondary sampling units (from continuous groupings of Census blocks) were selected using probability proportional to size, from which housing units and household members were sampled; (2) high-density supplemental sampling of census-block groups with greater than 5% density of target ethnic groups; (3) second respondent sampling to recruit participants from households from which a primary respondent had already been interviewed. Weights were developed to account for joint probabilities of selection for these three components and designed to allow the sample estimates to be nationally representative (Heeringa, Warner, Torres, Duan, Adams, & Berglund, 2004).

Respondents were adults residing in any of the fifty states and Washington, D.C. Trained interviewers with cultural and linguistic backgrounds similar to those of the respondent administered the survey in the respondent’s choice of Cantonese, English, Mandarin, Spanish, Tagalog, or Vietnamese with computer-assisted software. The survey was translated from English to the other languages using standard techniques (translation and back-translation). Interviews were conducted face-to-face unless respondents requested a telephone interview. Our sample includes a total of 2095 AA adults (1611 primary; 484 second respondents). The response rates (AAPOR-RR3 method) for primary and secondary respondents were 69.3%, and 73.7%, respectively (Heeringa et al., 2004). Further details of the study design can be found elsewhere (Alegria, Takeuchi, Canini, Duan, Shrout, & Meng, 2005; Heeringa et al., 2004).

The study oversampled Chinese (n=600), Vietnamese (n=508) and Filipinos (n=502)(Table 1). In addition, there are 148 Asian Indians, 115 Japanese, 84 Koreans, 38 Pacific Islanders, and 82 other Asians. About 53% of respondents were female, 65% were married/living with partner. They were 41 years old on average. Most (77%) were foreign-born, although two-thirds indicated “good” or “excellent” English proficiency. About 68% resided in the West, 16% in the Northeast, 9% in the Midwest and 8% in the South. Although 64% of respondents were employed and many had completed college (42%), a sizeable number of respondents were in poverty (18%) and did not complete high school (15%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the National Latino and Asian American Study Sample (weighted); n=2047

| Any DSM-IV disorder past 12 months, % | 9.19 |

| DSM-IV depressive disorder past 12 months, % | 4.73 |

| DSM-IV anxiety disorder past 12 months, % | 5.75 |

| Number of DSM-IV disorders, past 12 months, % | |

| None | 91.53 |

| One | 5.64 |

| Two or more | 2.83 |

| Everyday discrimination, mean (SE) | 1.82 (0.03) |

| Female, % | 52.55 |

| Age, mean (SE) | 41.23 (0.89) |

| Married/living with partner, % | 65.39 |

| Ethnic group, % | |

| Vietnamese | 12.93 |

| Filipino | 21.59 |

| Chinese | 28.69 |

| Other Asian or Pacific Islander | 36.79 |

| Generation,% | |

| 1. Born outside U.S. | 76.94 |

| 2. Born U.S. & parents born abroad | 13.68 |

| 3. Respondent and parents all born in the U.S. | 9.38 |

| English proficiency good/excellent, % | 66.19 |

| Region, % | |

| Midwest | 8.91 |

| Northeast | 15.67 |

| South | 7.83 |

| West | 67.59 |

| In poverty, % | 17.55 |

| Employed, % | 63.69 |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 15.15 |

| High school graduate | 42.90 |

| College graduate or more | 41.96 |

| Family cohesion, mean (SE) | 11.01 (0.06) |

| Physical health conditions, mean (SE) | 1.33 (0.06) |

| Self-rated health, mean (SE) | 3.49 (0.04) |

| Social desirability, mean (SE) | 2.26 (0.08) |

Measures

Dependent variables

The dependent variables were mental disorders using the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WHM-CIDI; World Health Organization, 1998). The WHM-CIDI is a cross-cultural psychiatric epidemiologic protocol that systematically operationalizes the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) and is designed to be administered by lay interviewers. Participants’ responses to the CIDI are then used to classify an individual as meeting the DSM-IV criteria for a mental disorder or not. Any 12-month disorder was a binary variable that indicated the presence or absence of any of the following 11 disorders: major depressive disorder, dysthymia, panic disorder, agoraphobia without panic, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, drug abuse, and drug dependence within the past 12 months.

We also examined two disorder categories that were relatively prevalent within our population and associated with discrimination in prior research: 12-month Depressive Disorders (major depressive disorder or dysthymia) and 12-month Anxiety Disorders (panic disorder, agoraphobia without panic, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder). These two outcomes were also binary. Substance use problems were not examined as distinct outcomes because of low rates (the prevalence of alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, drug abuse or drug dependence was 1.3%).

It is increasingly recognized that individuals may have more than one mental health problem. We also classified individuals as having no 12-month condition, any one of the 11, or two or more conditions (co-morbid).

Independent Variables

In following text, α and KR-20 respectively refer to Cronbach’s alpha and the Kuder-Richardson-20 indicators of internal consistency reliability for the present sample (Cudek, 1980).

Everyday discrimination

This 9-item scale (α = 0.91) adopted from the Detroit Area Study measures perceptions of chronic and routine unfair treatment (Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997). Respondents indicated how often (almost every day; at least once a week; a few times a month; a few times a year; less than once a year; never) they experienced: being treated with less courtesy than other people; treated with less respect; received poorer service at restaurants; people act as if they think you are not smart, as if they are afraid of you, as if you are dishonest, or as if you are not as good as they are; being called names or insulted; threatened or harassed. Following prior usage, items are summed and averaged across items. The range is from 1 (never) to 6 (experience discrimination almost every day).

Family cohesion

Using items derived from the Circumplex Model of Marital and Family Systems (Olson, 1986), respondents indicated agreement (1=strongly disagree to 4=strongly agree) with the following items: “Family members like to spend free time with each other,” “Family members feel very close to each other,” and “Family togetherness is very important.” The scale ranges from 3–12, with higher scores indicating greater family cohesion (α=0.92).

Poverty

A binary variable indicated whether the family income was beneath the federal poverty threshold for the corresponding family size in 2000 (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2006).

Acculturative stress

A10-item scale adapted from the Mexican American Prevalence and Services Survey (Vega, Kolody, Aguilar-Gaxioloa, Alderte, Catalano, & Caraveo-Anduaga, 1998) captured strains associated with culture change (Cervantes, Padilla, Amado, & Salgado de Snyder, 1990). Immigrant respondents indicated whether they felt: guilty for leaving behind family and friends; living in the U.S. has limited their contact with family/friends; the same level of respect as they had in their country of origin; difficulties interacting with others because of their language; treated badly because of their language skills; difficulties finding work because of ethnicity; were questioned about legal status; concerns of being deported; avoid seeking health services due to fear of immigration officials. The range was 0–10, with zero indicating the least and 10 the most acculturative stress (KR20=0.59). Only immigrants were asked about acculturative stress.

Physical health conditions

The WMH-CIDI checklist of lifetime physical problems (World Health Organization, 1998) assessed arthritis/rheumatism, chronic back/neck problems, frequent/severe headaches, other chronic pain, hay fever and other seasonal allergies, stroke, heart attack, heart disease, high blood pressure, asthma, tuberculosis, other chronic lung disease, diabetes/high blood sugar, ulcer in stomach/intestine, HIV/AIDS, epilepsy/seizure, and cancer. These items were summed (range 1–10).

Self-rated physical health

Respondents answered “how would you rate your overall physical health?” on a scale from “1=poor” to “5=excellent” (Idler, Hudson, & Leventhal, 1999).

Social desirability

The widely-used Marlowe and Crowne 10-item inventory (Crowne & Marlowe, 1960) was administered. Representative items included: “I never met a person that I didn’t like;” “I always win at games;” “I have never been bored.” Affirmative responses (yes/no) were summed. The range is 0–10, with higher scores indicating more social desirability (KR20=0.71).

Sociodemographic characteristics

Demographic information included: gender (1=female; 0=male), age, region (Northeast, South, Midwest and West), current employment (1=currently employed; 0=other), education and generation (0=immigrant respondent; 1=respondent U.S. born, but one parent is an immigrant; 2=respondent and both parents U.S. born), years in the United States, marital status (married/living with partner=1; 0=other). Language proficiency was assessed with, “How well do you speak English?” (1=excellent/good; 0=fair/poor).

Analytic Plan

Analyses employed multivariate regression techniques to model the association between discrimination and 12-month mental disorders. We examined whether these associations were explained by physical health conditions, other stressors, sociodemographic characteristics and social desirability. One outlier was removed and 47 cases with missing data were excluded, leaving a sample of 2047. All models were weighted to account for sample design using the Stata (v9.2) software (StataCorp, 2005).

Our first set of analyses used logistic regression to examine the potential association between discrimination and disorders (any, depressive, and anxiety) among the entire sample. Our second analyses used logistic regression, focusing on the immigrants (n=1,639). This analysis considered whether the effects of discrimination were explained by two factors that are especially relevant for immigrants, acculturative stress and years in the United States. Our third analyses used multinomial logistic regression to examine the potential association between discrimination and co-morbid disorders (ordered logit was not used because the parallel regression assumption was not met).

Results

Table 1 describes the participants’ responses. Participants reported high family cohesion (11.0 on a 3–12 scale). On average, respondents endorsed 2.3 of 10 indicators of social desirability. The prevalence of any DSM-IV disorder, any DSM-IV major depressive disorder, and DSM-IV anxiety disorder over the past 12 months was 9.19%, 4.73%, and 5.75%, respectively. Participants reported 1.3 chronic illnesses on average and a mean self-rated health of 3.5 (between good and very good). As with prior studies (Williams, et al., 1997) respondents perceived relatively infrequent encounters with everyday discrimination (1.8 on a 1–6 scale).

The bivariate associations between mental disorders and major covariates showed that discrimination, family cohesion, poverty, self-rated health, physical health conditions, and social desirability were associated with any disorder, depressive disorders and anxiety disorders (Table 2). These findings suggest the need to adjust the association between discrimination and mental disorders to avoid confounding.

Table 2.

Association between Self-Reported Discrimination and Mental Disorders. Logistic Regression. National Latino and Asian American Study (n=2047)

| ANY DISORDER | ANXIETY DISORDER | DEPRESSIVE DISORDER | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bivariate OR [CI] | Multivariate OR [CI] | Bivariate OR [CI] | Multivariate OR [CI] | Bivariate OR [CI] | Multivariate OR [CI] | |

| Discrimination | 2.24*** [1.80, 2.79] | 1.90*** [1.55, 2.32] | 2.70*** [2.06, 3.54] | 2.24*** [1.59, 3.15] | 1.94*** [1.40, 2.70] | 1.72*** [1.29, 2.30] |

| Poverty | 1.47 [0.95, 2.28] | 0.95 [0.54, 1.86] | 1.92* [1.00,3.70] | 0.98 [0.53, 1.82] | 1.80* [1.02,3.18] | 1.56 [0.80, 3.05] |

| Family Cohesion | 0.78*** [0.72, 0.85] | 0.91 [0.82, 1.02] | 0.72*** [0.66, 0.78] | 0.86** [0.77, 0.95] | 0.77*** [0.68, 0.87] | 0.86* [0.74, 0.99] |

| Physical Health Conditions | 1.37*** [1.22, 1.54] | 1.43** [1.27, 1.60] | 1.39*** [1.19, 1.62] | 1.54*** [1.23, 1.94] | 1.46*** [1.29, 1.66] | 1.43** [1.23, 1.60] |

| Self-Rated Physical Health | 0.77* [0.62, 0.95] | 0.93 [0.73,1.19] | 0.67** [0.53, 0.86] | 0.79 [0.57, 1.10] | 0.73* [0.55, 0.97] | 0.93 [0.68, 1.27] |

| Social Desirability | 0.85** [0.77, 0.94] | 0.89 [0.79, 1.00] | 0.79* [0.65, 0.95] | 0.84 [0.68, 1.04] | 0.87* [0.78, 0.98] | 0.91 [0.78, 1.06] |

N.B. The multivariate models are also adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, education, employment, marital status, language proficiency, generation and region.

OR = Odds Ratio

CI = 95% Confidence Interval

p>=0.05;

p>= 0.01;

p >=0.001

The multivariate models (Table 2) indicate that discrimination was a consistent predictor of having any, depressive and anxiety disorder even after accounting for a variety of factors. A one-unit increase in the report of discrimination was associated with a 1.9 greater odds of being classified with any DSM-IV mental disorder within the past 12 months, controlling for sociodemographic characteristics, family cohesion, poverty, physical health, and social desirability. Supplemental analyses (available from authors) determined that physical health conditions, but not poverty, family cohesion, or social desirability, was a major determinant of the decrease in the odds ratio from bivariate to the full model. Physical health conditions were also significantly associated with any disorders. Although significant in the bivariate analysis, social desirability was not significant in the multivariate model.

The patterns seen for any disorder were also seen for depressive and anxiety disorders. In both bivariate and multivariate models, discrimination was associated with a higher odds of being classified with depressive and anxiety disorders.

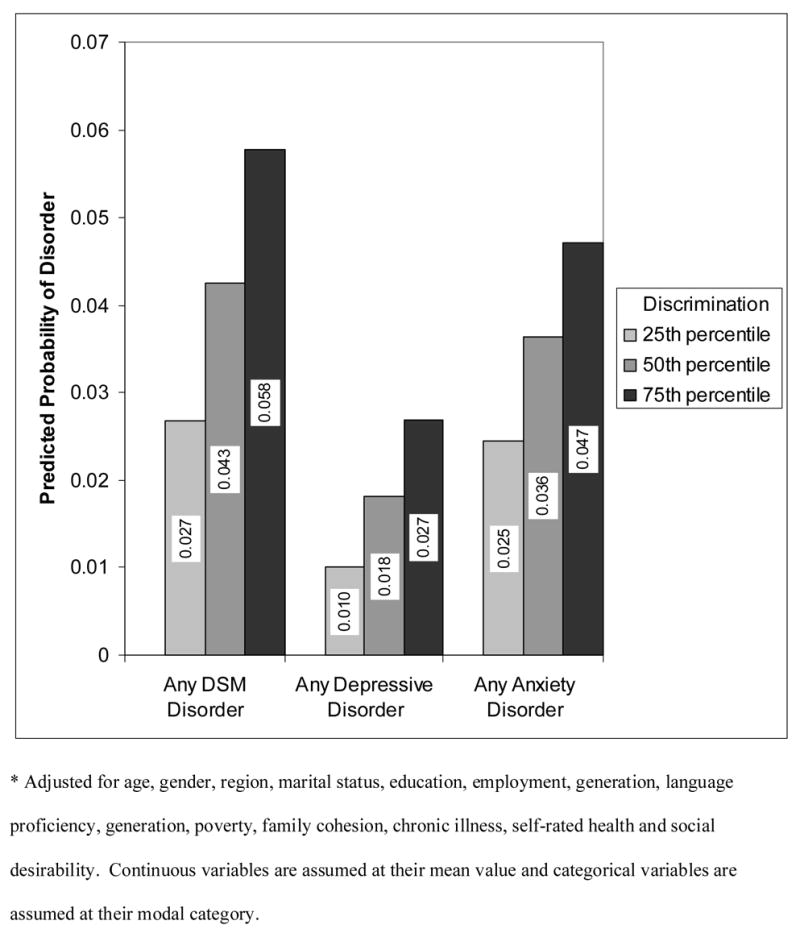

Probabilities are often more intuitively understood than odds (Figure 1). For someone reporting at the low quartile of discrimination (less than once a year), their predicted probability of any mental disorder was 0.027. Their probability of any disorder, 0.043, was nearly 60% greater if they perceived a median level of discrimination (approximately once a year). The probability of any disorder more than doubled to 0.058 if they were at the upper quartile of discrimination (a few times a year).

Figure 1.

Predicted Probabilities of 12-month DSM IV Disorders by Self-reported Discrimination (Adjusted)*: National Latino and Asian American Study (n=2095)

Although respondents had a greater probability of having an anxiety disorder than a depressive disorder, the effects of discrimination appeared stronger for depressive disorders. Specifically, the probability for anxiety disorders increased by 93% between the lower to the upper quartiles of discrimination. In contrast, the probability of a depressive disorder rose by 169% across the same range.

The analyses for immigrants only (Table 3) controlled for the covariates listed in Table 2 with two modifications: (1) generation was excluded (all immigrants are first generation); (2) acculturative stress and years in the U.S. were included. Again, discrimination was a consistent predictor across all models. Model A1 shows that acculturative stress (OR=1.18) was associated with any disorder. However, in the full model (A2), acculturative stress was non-significant. Similar patterns are evident for depressive disorders. For anxiety disorders, acculturative stress was not significant regardless of whether discrimination was in the model (C1 & C2). However, discrimination was a significant predictor of anxiety disorders. Diagnostic tests indicated that the non-significance of acculturative stress was not due to multicollinearity with discrimination. An additional concern is that some of the acculturative stress items (i.e. difficulties finding work because of ethnicity, treated badly because of language, level of respect in country of origin) overlap with everyday discrimination. In supplemental analyses (available from authors), we replicated our analyses excluding the overlapping items from the acculturative stress scale and found similar results. Thus, discrimination is a more robust predictor of mental disorders than acculturative stress and discrimination appears to account for the association between acculturative stress and depressive disorders.

Table 3.

Association between Self-Reported Discrimination and Mental Disorders among Immigrants. Logistic Regression. National Latino and Asian American Study (n=1639)

| Any Disorder | Anxiety Disorders | Depressive Disorders | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model A1 | Model A2 | Model B1 | Model B2 | Model C1 | Model C2 | |

| OR [CI] | OR [CI] | OR [CI] | OR [CI] | OR [CI] | OR [CI] | |

| Acculturative Stress | 1.18* [1.03, 1.35] | 1.09 [0.95, 1.25] | 1.10 [0.96, 1.27] | 1.02 [0.87, 1.21] | 1.31** [1.08, 1.60] | 1.18 [0.99, 1.42] |

| Years in the U.S. | 1.03 [0.99, 1.08] | 1.03 [0.98, 1.07] | 1.02 [0.98, 1.06] | 1.02 [0.97, 1.06] | 1.03 [0.96, 1.11] | 1.02 [0.95, 1.10] |

| Discrimination | 1.98** [1.41, 2.79 | 1.88** [1.24, 2.86] | 2.17** [1.31, 3.62] | |||

N.B. Controlling for age, gender, ethnicity, education, employment, marital status, language proficiency, region, poverty, family cohesion, physical health conditions, self-rated physical health, and social desirability.

OR = Odds Ratio

CI = 95% Confidence Interval

The association between discrimination and co-morbid mental disorders was estimated using multinomial logistic regression (Table 4). For the full sample, discrimination was associated with a higher risk (RRR=1.98) of having one disorder compared to no disorders. Further, discrimination was associated with a higher risk of having two or more disorders compared to having no disorders (RRR=3.07). A similar pattern emerged for the immigrant subset of our study which further controls for acculturative stress and years in the U.S. Supplemental analyses (not shown) using Poisson regression to model the association between counts of mental disorders and discrimination found similar results. Hence, discrimination was not only associated with having a mental order, but also with increased risk of having multiple mental disorders. Additional analyses considered whether gender, generation or years in the U.S. moderated discrimination, but these interactions were non-significant.

Table 4.

Association between Self-Reported Discrimination and Co-Morbid 12-Month DSM-IV Disorders for the Full and Immigrant Samples. Multinomial logistic regression. National Latino & Asian American Study

| Zero Disorders | One Disorder | Two or more disorders | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRR | CI | RRR | CI | |||

| Full Sample (n=2047) Discriminationa | Reference | 1.98 | (1.37, 2.85)*** | 3.07 | (1.93, 4.87)*** | |

| Immigrant Sample (n=1639) Discriminationb | Reference | 1.74 | (1.17, 2.58)*** | 3.18 | (1.80, 5.62)*** | |

Controlling for age, gender, ethnicity, education, employment, marital status, language proficiency, generation, region, poverty, family cohesion, physical health conditions, self-rated physical health, and social desirability

Controlling for same covariates in (a) except that generation is excluded and years in the U.S. and acculturative stress are included.

RRR=Relative Risk Ratio

CI = 95% Confidence Interval

p>=0.05;

p>= 0.01;

p >=0.001

Discussion

Our data indicate that self-reported discrimination was associated with 12-month mental disorders and co-morbidity among AAs. We challenged the association between discrimination and mental disorders with several potential confounders, including other stressors, health conditions, and social desirability. Discrimination was a robust predictor of mental disorders when these factors and other sociodemographic characteristics were controlled.

One challenge came from other stressors as measured by low family cohesion, poverty, and acculturative strains. Most studies of discrimination do not consider other potential stressors, leaving open whether discrimination constitutes a unique stressor or simply captures these unmeasured stressors. Although family cohesion, poverty and acculturative stress were associated with mental disorders in unadjusted models, they were not significantly associated with disorders in fully adjusted models. Discrimination, however, remained an important correlate of mental disorders. We did not measure all possible stressors (e.g. job strain), and focused on specific types of stressors rather than more global inventories (e.g. life events). However, our findings indicate that discrimination is associated with mental disorders independent of poverty, family cohesion and acculturative stress.

Remarkably, even among immigrants, discrimination appeared to be a more important predictor of mental disorders than acculturative stress or years in the United States. It is often reported that immigrants’ mental health worsens due to the stressors associated with adjustment in a new culture (Vega, Sribney, Aguilar-Gaxiola, & Kolody, 2004). Although acculturative stress was associated with mental disorders, acculturative stress was no longer significant once we included discrimination. Finch and colleagues (2001) also found that acculturative stress (measured by language conflict and legal status) was not associated with chronic health conditions among Mexican Americans after including discrimination. In contrast, Noh and Kasper (2003) reported that acculturative stress was associated with depression among Koreans in Toronto, but that this association varied by level of discrimination and type of coping response. Gee, Ryan, Holt, and Laflamme (2006) reported that the association between discrimination and mental health strengthened with increasing years in the U.S. among Latino and Black immigrants. However, the current data did not find a main effect for years in the U.S. or an interaction between years and discrimination. Further research is needed to clarify the potential relationships between discrimination and acculturation. That said, our findings and the literature indicate that discrimination is associated with health independent of acculturation. Hence, our findings do not invalidate the claim that adjustment is a stressful process, but do buttress arguments that an important issue in cultural adjustment involves dealing with discrimination (Berry, 2003; Finch, Hummer, Kolody & Vega, 2001).

The second challenge involved physical health conditions. Physical health attenuated, but did not eliminate the association between discrimination and mental disorders. This finding is consistent with arguments that discrimination, mental disorders and physical conditions lie on a common causal pathway. That is, discrimination may directly cause mental and physical disorders and these disorders may cause one another. For example, discrimination may lead to heart disease which leads to anxiety. Thus, part of the relationship between discrimination and mental health may be mediated by physical health conditions (conversely, physical health may be mediated by mental health). We are unable to establish these pathways with cross-sectional data, but these ideas should be investigated in future research.

The third challenge involved social desirability, a reporting tendency associated with the seeking of approval or the avoidance of disapproval. These ideas resonate with “loss of face,” the avoidance of shaming oneself or one’s family, which may be especially important for AAs (Gong, et al., 2003; Zane & Yeh, 2002). In our study, social desirability did not influence the relationship between discrimination and mental disorders. This finding is important because response factors are always a threat to the validity of self-reported data. Other studies have found that the association between self-reported ethnic harassment and mental health is not confounded by affective disposition (tendency to complain about innocuous events) (Schneider et al., 2000). Although this gives us more confidence, future work should examine other potential response (e.g. memory) and personality factors (e.g. optimism). We discuss some other response factors below.

The associations between discrimination and health were stronger for depressive disorders than for anxiety disorders, suggesting that the potential effects of discrimination vary by outcome. Prior studies have also found associations between discrimination and depression and anxiety among Asians in the U.S. and internationally (Bhui, et al., 2005; Gee, 2002; Karlsen & Nazroo, 2002; Noh & Kaspar, 2003). Although AAs were not examined, Kessler and colleagues (1999) found that everyday discrimination (using a measure similar to ours) was associated with a 2.1 greater odds of depression and 3.3 greater odds of generalized anxiety disorder among the U.S. general population. It would have been informative to disaggregate our disorders into more specific categories, but small numbers of cases precluded disaggregation. Further, health associations likely vary by the type of discrimination measured. For example, the potential effects of structural discrimination may differ from those of interpersonal discrimination (Gee, 2002). Our study only considers interpersonal discrimination, therefore it is possible that the exclusion of other types of discrimination (e.g. structural, internalized oppression) may underestimate the full association of discrimination with mental disorders.

The average levels of discrimination reported by AAs nationwide (1.8 on a 1–6 point scale) are relatively close to those reported by African Americans in Detroit (2.3, using the same scale) (Williams et al., 1997). This suggests that discrimination may be a shared experience that may help foster bridges between diverse groups. Further, discrimination may have been underreported for several reasons. First, the everyday discrimination scale was designed for African Americans and does not measure several phenomena that may be especially relevant for Asians, such as being a “perpetual foreigner” or stereotyped as passive (Liang et al., 2004; Young & Takeuchi, 1998). Second, potential undesirable consequences of reporting, including invalidation by others, may cause individuals to reappraise a discriminatory incident as non-discriminatory to avoid such challenges (Harrell, 2000; Kuo, 1995). Third, experiences of discrimination may be simply forgotten or unrecognized. Underreporting of discrimination would tend to bias our findings towards the null.

Discrimination may also be overreported in some circumstances, as when individuals encounter paranoia. This raises questions about the causal direction between discrimination and mental disorders. That is, although we presume that discrimination causes mental disorders, it is possible that mental disorders cause one to experience and/or perceive discrimination. We cannot establish these directions given cross-sectional data. However, several prospective studies have reported that discrimination predicts illness (Jackson, et al., 1996; Schulz, Gravlee, Williams, Israel, Mentz, & Rowe, 2006). Pavalko, Mossakowski, and Hamilton (2003) found that self-reported discrimination predicted illness, but that illness did not predict reports of discrimination over a period of seven years. That said, more longitudinal research is needed.

Before concluding, a few additional caveats should be mentioned. First, the NLAAS oversampled Chinese, Filipinos and Vietnamese, but we did not disaggregate our analysis by ethnic subgroup because cell sizes became sparse. In NLAAS, Filipinos reported the highest levels of discrimination (mean=1.9) and Vietnamese the lowest (mean=1.5), suggesting that future studies should investigate possibly higher risk among Filipinos. Further, our sample includes some Pacific Islanders, but their experiences are largely not represented in our data. Hence, our analyses apply to AAs in the aggregate, but future research should investigate Pacific Islanders and subgroups within Asians and Pacific Islanders. Second, we focus on psychiatric disorders as defined by the DSM-IV. While this allows for comparability with other studies, DSM-IV criteria may be biased towards western ways of expressing mental health problems and may underestimate rates of mental disorders (Takeuchi, Chun, Gong, & Shen, 2002).

Despite the caveats, our study has several strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first nationally representative study of discrimination and mental disorders among AAs. Additionally, we employ standard measures that allow for comparability with other studies. Finally, we control for a number of important factors, including social desirability.

In conclusion, our study finds that self-reported discrimination is associated with greater chance of having a mental disorder and multiple mental disorders within the past year among Asian Americans. It is important to note that the analyses presented here represent a conservative test of the association between self-reported discrimination and mental disorders. That perceived discrimination still has an association with mental disorders given the other variables is impressive. There are several avenues for future research, including an assessment of the factors that may buffer against the effects of discrimination, ethnic subgroup differences, and a more detailed examination of the specific disorders. Moreover, there is a critical need for longitudinal studies. It is still premature to conclude that discrimination causes mental disorders, but these caveats do not preclude the continuation and development of civil rights legislation and multicultural training. Indeed, if discrimination is found to be a causal risk factor for mental disorders, as our results imply, then policies designed to promote civil rights may not only buttress the foundations of a civil society, but also a healthy one.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wendy Lin and several anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on a prior draft of this paper. This article is dedicated in memorium of our dear friend, Lucy Shum, and her fight for social justice and mental health parity.

Footnotes

Author Comments: The National Latino and Asian American Study is funded by the National Institute of Mental Health Grant # U01 MH62209 and U01 MH62207 with additional support from the Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Dr. Gilbert C Gee, Email: gilgee@umich.edu, University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI UNITED STATES

Michael Spencer, Email: spencerm@umich.edu, University of Michigan.

Juan Chen, Email: juanc@umich.edu, University of Michigan.

Tiffany Yip, Email: tyip@fordham.edu, Fordham University.

David T. Takeuchi, Email: dt5@u.washington.edu, University of Washington.

References

- Alegria M, Takeuchi DT, Canino G, Duan N, Shrout P, Meng X. Considering context, place, and culture: The National Latino and Asian American study. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2005;13:208–220. doi: 10.1002/mpr.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Conceptual approaches to acculturation. In: Chun K, Organista PB, Marin G, editors. Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, Kim U, Minde T, Mok D. Comparative studies of acculturative stress. International Migration Review. 1987;21:491–511. [Google Scholar]

- Beverridge RM, Berg CA, Wiebe DJ, Palmer DL. Mother and adolescent representations of illness ownership and stressful events surrounding diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2006;31:818–827. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhui K, Stansfeld S, McKenzie K, Karlsen S, Nazroo J, Weich S. Racial/ethnic discrimination and common mental disorders among workers: Findings from the EMPIRIC Study of Ethnic Minority groups in the United Kingdom. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:496–501. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.033274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobo L. Racial attitudes and relations at the close of the Twentieth Century. In: Smelser N, Wilson WJ, Mitchell F, editors. America becoming: Racial trends and their implications. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2000. pp. 262–299. [Google Scholar]

- Caughy MO, O’Campo P, Muntaner C. Experiences of racism among African American parents and the mental health of their preschool-aged children. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:2118–2124. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes RC, Padilla AM, Amado M, Salgado de Snyder N. Reliability and validity of the Hispanic Stress Inventory. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1990;12:76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Chan S. Asian Americans: An interpretive history. Boston, MA: Twayne Publishers; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson A, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans. American Psychologist. 1999;54:805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee of 100. American attitudes towards Chinese Americans and Asian Americans. New York: Committee of 100; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Crane DR, Ngai SW, Larson JH, Hafen M. The influence of family functioning and parent-adolescent acculturation on North American Chinese adolescent outcomes. Family Relations. 2005;54:400–410. [Google Scholar]

- Creed F. The importance of depression following myocardial infarction. Heart. 1999;82:406–408. doi: 10.1136/hrt.82.4.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowne DP, Marlowe D. A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1960;24:349–354. doi: 10.1037/h0047358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudek R. A comparative study of indices for internal consistency. Journal of Educational Measurement. 1980;17:117–130. [Google Scholar]

- DuBois DL, Burk-Braxton C, Swenson LP, Tevendale HD, Hardesty JL. Race and gender invluences on adjustment in early adolescence. Child Development. 2002;73:1573–1592. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton WW, Muntaner C. Socioeconomic stratification and mental disorder. In: Horwitz AV, Scheid TL, editors. A handbook for the study of mental health: Social contexts, theories, and systems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 259–283. [Google Scholar]

- Finch B, Kolody B, Vega WA. Perceived discrimination and depression among Mexican-origin adults in California. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41:295–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch B, Vega WA. Acculturation stress, social support, and self-rated health among Latinos in California. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2003;5:109–117. doi: 10.1023/a:1023987717921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch BA, Hummer RA, Kolody B, Vega WA. The role of discrimination and acculturative stress in Mexican-origin Adults’ physical health. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2001;23:399–429. [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC. A multilevel analysis of the relationship between institutional racial discrimination and health status. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:615–623. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Chen J, Spencer M, See S, Kuester O, Tran D, Takeuchi DT. Social support as a buffer for perceived unfair treatment among Filipino Americans: Differences between San Francisco and Honolulu. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:677–684. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Delva J, Takeuchi DT. Perceived unfair treatment and the use of prescription medications, illicit drugs and alcohol dependence among Filipino Americans. American Journal of Public Health. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.075739. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Ryan AM, Laflamme D, Holt J. The association between self-reported discrimination and mental health status among African descendents, Mexican Americans and Other Latinos in the New Hampshire REACH Study: The added dimension of immigration. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1821–1828. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.080085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong F, Gage SL, Tacata L. Helpseeking behavior among Filipino Americans: A cultural analysis of face and language. Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31:469–488. [Google Scholar]

- Goto SG, Gee GC, Takeuchi DT. Strangers still? The experience of discrimination among Chinese Americans. Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30:211–224. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP. A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:42–57. doi: 10.1037/h0087722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris TL, Molock SD. Cultural orientation, family cohesion, and family support in suicide ideation and depression among African American college students. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior. 2000;30:341–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heerenga S, Warner J, Torres M, Duan N, Adams T, Berglund P. Sample designs and sampling methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:221–240. doi: 10.1002/mpr.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovey JD. Acculturative stress, depression, and suicidal ideation in Mexican immigrants. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2000;6:134–151. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.6.2.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, Hudson SV, Leventhal H. The meanings of self-ratings of health. Research on Aging. 1999;21:458–476. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Brown TN, Williams DR, Torres M, Sellers SL, Brown K. Racism and the physical and mental health status of African Americans: a thirteen year national panel study. Ethnicity and Disease. 1996;6:132–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C. Levels of racism: A theoretical framework and a gardener’s tale. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:1212–1215. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.8.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsen S, Nazroo JY. Relation between racial discrimination, social class, and health among ethnic minority groups. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:624–631. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merkangas KR, Rush J, Walters EE, Wang PS. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Journal of American Medical Association. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Michelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40:208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt JK, McGrath E. Social desirability responding in the measurement of assertive behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1979;47:640–642. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. Embodying inequality: a review of concepts, measures, and methods for studying health consequences of discrimination. International Journal of Health Services. 1999;29:295–352. doi: 10.2190/M11W-VWXE-KQM9-G97Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Sidney S. Racial discrimination and blood pressure: the CARDIA study of young Black and White adults. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86A:1370–1378. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.10.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:1576–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo WH. Coping with racial discrimination: The case of Asian Americans. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 1995;18:109–127. [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, Klonoff EA. The schedule of racist events: A measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. Journal of Black Psychology. 1996;22:144–168. [Google Scholar]

- Lai E, Arguelles D. The new face of Asian Pacific America. San Francisco: Asian Week; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Liang CTH, Li LC, Kim BSK. The Asian American Racism-Related Stress Inventory: Development, factor analysis, reliability, and validity. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51:103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Liebkind K. Acculturation and stress: Vietnamese youth in Finland. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1996;27:61–180. [Google Scholar]

- Lien P. Public resistance to electing Asian Americans in Southern California. Journal of Asian American Studies. 2002;5.1:51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Mossakowski KN. Coping with perceived discrimination: Does ethnic identity protect mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:318–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Measuring racial discrimination. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Noh S, Beiser M, Kaspar V, Hou F, Rummens J. Perceived racial discrimination, depression, and coping: A study of Southeast Asian refugees in Canada. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40:193–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh S, Kaspar V. Perceived discrimination and depression: Moderating effects of coping, acculturation and ethnic support. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:232–238. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Larson J, Grayson C. Explaining the gender difference in depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:1061–1072. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.5.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okihiro G. The Columbia guide to Asian America history: A resource guide to Asian American literature. New York: Columbia University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Olson DH. Circumplex Model VII: Validation Studies and FACES III. Family Process. 1986;25:337–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1986.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson JM, Garwick AW. The impact of chronic illness on families: A family systems perspective. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1994;16:131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus DL. Measurement and control of response bias. In: Robinson JP, Shaver P, Wrightsman LS, editors. Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes. San Diego: Academic Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Pavalko E, Mossakowski KN, Hamilton V. Does perceived discrimination affect health? Longitudinal relationships between work discrimination and women’s physical and emotional health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:18–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlow HM, Danoff-Burg S, Swenson RR, Pulgiano D. The impact of ecological risk and perceived discrimination on the psychological adjustment of African American and European youth. Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;32:375–389. [Google Scholar]

- Pernice R, Brook J. Refugees’ and immigrants’ mental health: association of demographic and post-immigration factors. Journal of Social Psychology. 1996;136:511–519. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1996.9714033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinherz HZ, Paradis AD, Giaconia RM, Stashwick CK, Fitzmaurice G. Childhood and adolescent predictors of major depression in the transition to adulthood. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:2141–2147. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roose SP, Glassman AH, Seidman SN. Relationship between depression and other medical illnesses. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;286:1687–1690. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.14.1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut R. The crucible within: ethnic identity, self-esteem, and segmented assimilation among children of immigrants. International Migration Review. 1994;28:748–794. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider KT, Hitlan RT, Radhakrishnan P. An examination of the nature and correlates of ethnic harassment experiences in multiple contexts. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2000;85:3–12. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.85.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz AJ, Gravlee CC, Williams DR, Israel B, Mentz G, Rowe Z. Discrimination, symptoms of depression, and self-rated health among African American women in Detroit: Results from a longitudinal analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1265–1270. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MS, Chen J. Discrimination and mental health service use among Chinese Americans. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:809–814. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.5.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 9. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi DT, Chun CA, Gong F, Shen H. Cultural expressions of distress. Health. 2002;6:221–235. [Google Scholar]

- Turner MA, Ross SL, Bednarz BA, Herbig C, Lee SJ. Discrimination in metropolitan housing markets: Phase 2 Asians and Pacific Islanders. Washington, D.C.: The Urban Institute, Metropolitan Housing and Communities Policy Center; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of the Census. Poverty Thresholds in 2000. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. Civil rights issues facing Asian Americans in the 1990s. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Commission on Civil Rights; 1992. pp. 1–233. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental health: Culture, race and ethnicity--A supplement to Mental health: A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD.: US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration, Center for Mental Health Services; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umemoto K. From Vincent Chen to Joseph Ileto: Asian Pacific Americans and hate crime policy. In: Ong P, editor. The state of Asian Pacific America: Transforming race relations. Los Angeles: LEAP Asian Pacific American Public Policy Institute and UCLA Asian American Studies Center; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vega W, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxioloa S, Alderte E, Catalano R, Caraveo-Anduaga H. Lifetime prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders among urban and rural Mexican Americans in California. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:771–778. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.9.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Sribney WM, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Kolody B. 12-Month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders among Mexican Americans: nativity, social assimilation, and age determinants. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2004;192:532–541. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000135477.57357.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B. The nature of stressors. In: Horwitz AV, Scheid TL, editors. A handbook for the study of mental health: Social contexts, theories, and systems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 176–197. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Neighbors H, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:200–208. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Willams-Morris R. Racism and mental health: the African American experience. Ethnicity and Health. 2000;5:243–268. doi: 10.1080/713667453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socioeconoomic status, stress, and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2:335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Disability Assessment Schedule II (WHO-DAS II) Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh CJ, Arora AK, Inose M, Okubo Y, Li RH, Greene P. The cultural adjustment and mental health of Japanese immigrant youth. Adolescence. 2003;38:481–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H, Wilson PA, Chae DH, Cheng JF. Do family and friendship networks protect against the influence of discrimination and HIV risk among Asian and Pacific Islander gay men? AIDS Educ Prev. 2004;16:84–100. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.1.84.27719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young K, Takeuchi DT. Racism. In: Lee LC, Zane NWS, editors. Handbook of Asian American Psychology. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1998. pp. 401–432. [Google Scholar]

- Zane N, Yeh M. The use of culturally based variables in assessment: Studies on loss of face. In: Kurasaki K, Okazaki S, Sue S, editors. Asian American mental health: Assessment theories and methods. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zia H. Asian American dreams: The emergence of an American people. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2000. [Google Scholar]