Abstract

Objectives

To synthesise data on the impact on health and key socioeconomic determinants of health and health inequalities reported in evaluations of national UK regeneration programmes.

Data Sources

Eight electronic databases were searched from 1980 to 2004 (IBSS, COPAC, HMIC, IDOX, INSIDE, Medline, Urbadisc/Accompline, Web of Knowledge). Bibliographies of located documents and relevant web sites were searched. Experts and government departmental libraries were also contacted.

Review methods

Evaluations that reported achievements drawing on data from at least two target areas of a national urban regeneration programme in the UK were included. Process evaluations and evaluations reporting only business outcomes were excluded. All methods of evaluation were included. Impact data on direct health outcomes and direct measures of socioeconomic determinants of health were narratively synthesised.

Results

19 evaluations reported impacts on health or socioeconomic determinants of health; data from 10 evaluations were synthesised. Three evaluations reported health impacts; in one evaluation three of four measures of self reported health deteriorated, typically by around 4%. Two other evaluations reported overall reductions in mortality rates. Most socioeconomic outcomes assessed showed an overall improvement after regeneration investment; however, the effect size was often similar to national trends. In addition, some evaluations reported adverse impacts.

Conclusion

There is little evidence of the impact of national urban regeneration investment on socioeconomic or health outcomes. Where impacts have been assessed, these are often small and positive but adverse impacts have also occurred. Impact data from future evaluations are required to inform healthy public policy; in the meantime work to exploit and synthesise “best available” data is required.

Keywords: evidence based policy, health inequalities, regeneration, systematic review, healthy public policy

Policies and interventions that tackle the root causes of poor health have recently been promoted by the UK and other EU governments as an important component of national strategies to improve health and reduce health inequalities.1,2,3,4,5,6 The need to ground these strategies on evidence has also been highlighted.2,7,8 Most recently the Wanless report stated that “every opportunity to generate evidence from current policy and practice needs to be realised”, and pointed to the value of systematic review methods in this regard.2 National programmes of urban regeneration, or area based initiatives (ABIs), are one example of large scale investment tackling urban deprivation and the socioeconomic determinants of health, for example, employment, education, income, and housing; in the UK £11 billion has been spent on these initiatives over the past 20 years. The potential for this significant investment to lead to health improvement may seem obvious and indeed is currently used as a justification of such large scale investment (box 1).1,9,10,11 However a systematic review of the impacts of ABI programmes on health or the socioeconomic determinants of health has not yet been done.

The dearth of data validating links between regeneration12 or housing investment within regeneration programmes13 and subsequent health improvement has already been established in both systematic13 and non‐systematic reviews.12 But these reviews have relied largely on the results of formal research studies. Other relevant data and valuable lessons from previous policy interventions may remain hidden within government reports of policy evaluations. For example, large scale evaluations of ABIs are commissioned by government departments but their findings are rarely published in academic journals and the public health value of the evaluations' findings seems to have been overlooked. In addition, evaluations of ABI programmes may be more likely to prioritise assessments of socioeconomic outcomes, over health outcomes. Impacts on socioeconomic outcomes have been recommended as a pragmatic and more immediate alternative to assessments of health impacts where health impact data are absent or difficult to obtain.4 A systematic examination of both the health and the socioeconomic impacts reported in national ABI evaluations may therefore allow exactly the type of synthesis called for by Wanless.2

What is the evidence that national programmes of urban regeneration (ABIs) improve health?

We carried out a synthesis of evaluations of national ABI programmes in the UK over 24 years (1980–2004) to examine the evidence that such major investments can have an impact on population health, the socioeconomic determinants of health, and health inequalities. We used existing systematic review methods for this synthesis.14

Methods

Search strategy

We searched for the original reports of national evaluations of all the UK government's nine national ABI programmes since 1980. (A brief description of each ABI programme's activities, focus, years of implementation, and level of funding in the UK since 1980 is provided in table 1.) Eight electronic databases were searched (Bath Information and Data Services International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (BIDS IBSS, 1980–2004), COPAC (1980–2004), Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC, 1988–2004), IDOX Information Service (1980–2004), INSIDE (1980–2004), Ovid Medline (1980–2004), Urbadisc/Accompline (1980–2004), Web of Knowledge (1980–2004)). Because of the specific nature of the review topic, the databases were searched for any text containing the programme names or their commonly used abbreviations (for example, SRB for single regeneration budget). Relevant government departmental libraries were contacted for details of archived reports. Bibliographies of located documents and identified relevant web sites were also searched (http://www.odpm.gov.uk/,http://www.landecon.cam.ac.uk/urban/urgsrb.html). Authors of national ABI evaluations and an author's (AK) own experience in this specialist field were drawn on to identify experts; identified experts were contacted to ask about further documentation available that may not have been identified by our search strategy.

Table 1 Main activities and funding of national ABI programmes in the UK since 1969.

| ABI programme (ordered by date)+estimated expenditure | Main focus of programme |

|---|---|

| Urban Programme 1969–1980s about £274m/year | Grant based programme to deal with areas of special social need through supplementation of existing programmes covering economic, environmental, employment and social projects. |

| Urban Development Corporations (UDC) 1981–1998 £2120m | Property and economic regeneration to attract inward investment. |

| Estate Action 1985–1995 £1975m | Housing led regeneration, addressing both improvements to physical aspects of housing as well as housing management.47 |

| New Life for Urban Scotland (New Life) 1988–1998 £485m | Comprehensive multi‐agency regeneration programme to improve housing, environment, service provision, training and employment for local people in four areas.48 |

| Small Urban Renewal Initiatives (SURI) 1990–2003 £160m+ | Housing led regeneration to widen housing choice, improve quality of housing quality and the local environment, improve economic prospects and lever public and private funding.27 |

| City Challenge 1992–1998 £1162.5m | Comprehensive multi‐agency regeneration to improve quality of life of residents in run down areas.35 |

| Single Regeneration Budget (SRB) 1995–2001 £5703m + £20301m from private sector | Comprehensive multi‐agency regeneration through initiatives on employment, training, economic growth, housing, crime, environment, ethnic minorities and quality of life (including health, sport, and cultural opportunities).32 |

| Regeneration Partnerships (now known as Social Inclusion Partnerships (SIPs)) 1996 £52m | Coordinated approach to tackle and prevent social exclusion and demonstrate innovative practices. Main activities focus on education and training, and initiatives to reduce poverty, crime, and promote employment, enterprise, empowerment, and health.34 |

| New Deal for Communities (NDC) £2000m 1998–2008 | Neighbourhood based programme delivered through multi‐agency partnerships. Aims: to reduce inequalities in crime, worklessness, education, housing, and health between the 39 target areas and the rest of England. Key characteristics of this programme are: long term commitment to deliver real change, communities in partnership with key agencies, community involvement and ownership, joined up thinking and solutions, and action based on evidence about “what works” and what doesn't.49 |

Box 1 The potential for health improvement is currently an important justification for large scale public investment in ABIs

“Local neighbourhood renewal and other regeneration initiatives are in a particularly good position to address health inequalities because they have responsibility for dealing with the wider determinants that have impact on people's physical and mental health.”1

“The benefits of including health in the strategy of regeneration strategy are twofold. First there are the direct benefits of improving peoples' physical and mental health and wellbeing. Second are the indirect benefits for employment, quality of life, levels of stress and the cost of hospital admissions or medicines.”9

“Area regeneration has a key contribution to make to improving health. It tackles the social, economic, and environmental problems of multiple deprivation. And it embodies the concerted approach the government seeks to foster.”10

Aims of current national ABI (New Deal for Communities). “Lower worklessness and crime, and better health, skills, housing and physical environment.”

To narrow the gap on these measures between the most deprived neighbourhoods and the rest of the country.”11

A tally of available funding for programmes included in our review produced an estimate that over £11bn (16bn euros) of public money has been spent on ABIs in England alone between 1980 and 2002.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Evaluations that reported achievements or impacts drawing on data from at least two target areas of a national ABI programme in the UK were included. Evaluations of single target areas or of projects within programme areas were excluded as the review aimed to assess the general impacts of a national programme; we assumed that single area evaluations may be less able than multi‐area evaluations to account for local peculiarities that may influence outcomes. Annual reports and routine audits of programme activity were excluded unless they were presented as an evaluation or assessment of the programme's achievements. Where it was clear that the document reported on a process or strategy for delivering urban regeneration rather than on the outcomes of ABI investment these documents were excluded (for example, the use of inter‐agency partnership working in the delivery of ABI programmes). All methods of evaluation were included (for example, qualitative, quantitative case study, retrospective or prospective studies). Evaluations reporting only business and enterprise outcomes were not included.

Screening and selection

Titles of identified documents were screened by one reviewer to exclude obviously irrelevant or duplicate documents, after which titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers. Where there was disagreement or uncertainty the full document was obtained and screened independently by two reviewers. Data extraction was carried out by RA and HT.

Data extraction

Impact data, defined as a measure of change in a given outcome over time, were extracted for health and selected socioeconomic outcomes. Health outcomes were any direct measure of health (quality of life, wellbeing, health, morbidity, mortality) or intermediate measure of health (for example, registration/use/satisfaction with local health services). Socioeconomic outcomes relevant to the determinants of health were defined as outcomes pertaining to housing, education, training, income, or employment. These included both direct measures (for example, household income, housing quality) and intermediate measures (receipt of welfare, satisfaction, with housing). Impacts on crime and neighbourhood outcomes (for example, satisfaction with local shops) were also extracted. Gross output data (reports of monies spent and investment activity, for example, number of dwellings built or improved, use of new sports centre) were not extracted.

Data synthesis

Impact data on direct health outcomes and direct measures of socioeconomic determinants of health were synthesised. Stakeholders' and evaluators' overall assessment of impacts on direct outcomes were not included in the synthesis. Intermediate outcomes were not included in the data synthesis.

Results

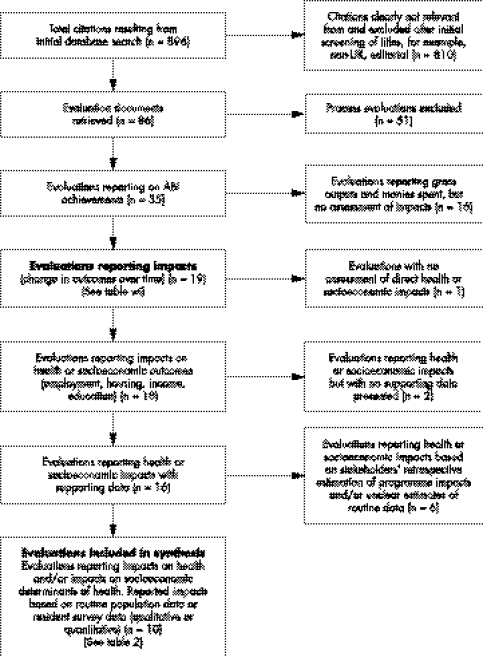

A total of 896 references were identified of which 86 initially appeared relevant; 35 were included in the final review (fig 1). Sixteen evaluations used gross outputs exclusively to report programme achievement. Nineteen evaluations assessed health and social impacts and were included in the first stage of the review (see table w1 on line http://www.jech.com/supplemental).15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34

Figure 1 Flow diagram of identifying included evaluations.

Impact evaluations: methods, data quality and choice of outcome measures

Nine evaluations were carried out prospectively.23,24,26,27,28,30,31,34 All but two20,26 of the impact evaluations used a case study approach, where the evaluators selected a few sites to represent the national programme. Detailed reporting of evaluation methods, data sources, and sample sizes was poor; in two evaluations some impacts were reported without any supporting data.23,24 Furthermore, evaluators frequently reported that data on included outcomes were unavailable, resulting in non‐reporting17,23,24,29 or presentation of incomplete data in the final document.16,19,28,34

Evaluations assessing impacts relied heavily on routine statistics collected by the UK government as well as stakeholders' perceptions or the evaluators' overall estimates of impacts. Six evaluations included a prospective survey of residents,23,24,26,28,32,34 one of which was a panel survey of the same residents at both time points.32 Ten of the 19 impact evaluations reported impacts on direct health or socioeconomic outcomes (table 2).18,22,25,26,27,28,30,31,32,34

Table 2 Summary of direct impacts on health and socioeconomic status reported in evaluations of national (UK) area based initiatives.

| Programme (dates of data collection)Number of case study areas included in evaluation/total number of target areas included in programme | Outcome measure used(number of case study areas where data reported/no of case study areas included in evaluation) | Overall impact and range across case study areas | Direction of overall impact | Range of effects across case study areas includes zero * | Improvement reported over and above national or regional trends over same time period * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impacts on health outcomes | |||||

| SRB32 (1996 v 1999)Panel survey in three target areas | self reported “good health” | 44% v 40%, −4% (range −6% to +2%) | Deterioration | Yes | |

| self reported “not good health” | 26% v 28%, +2% (range −7% to +8%) | Deterioration | Yes | ||

| self reported “health worse in past three years” | 29% v 35%, +6% (range 0% to +13%) | Deterioration | Yes | ||

| self reported “health improved in past three years” | 7% v 10%, +3% (range +2% to +4%) | Improvement | No | ||

| New Life26 (1988 v 1994)All four target areas | standardised mortality (three areas) | 131 v 114, −17 (range −29 to +12) | Improvement | Yes | |

| SRB31 (1994 v 1998)Two case study areas | crude mortality rate (%per 1000) (one area) | 12.5% v 13.1%, −0.6% (range −1% to −0.2%) | Improvement | No | |

| standardised mortality (England = 100) (one area) | 122 v 118 (range −7 to −1) | Improvement | No | ||

| Impacts on employment | |||||

| New Life26 (1988 v 1998)All four target areas | employment rate (% of working age in employment) | 41% v 47%, +6% (range −9% to +20%) | Improvement | Yes | |

| SRB32 (1996 v 1999)Panel survey in three target areas | employment rate (% of working age in employment) | 56% v 60%, +4% (range +3% to +5%) (England data 1996–1999, +4%, 78% v 82%) | Improvement | No | No |

| SURI (1993 1998)27 | number of households with at least one person economically active | +9%, compared with non‐SURI area −5% | Improvement | Yes | |

| Impacts on unemployment | |||||

| Urban Programme18 (1981/82 v 1991)Two target areas | % unemployed | +3.25% London data 1981 v 1991 +0.5% | Deterioration | No | |

| SRB31 (1995 v 1997)Two target areas | % of population unemployed (one area) | 4.5% v 3.2%, −1.3% (range −1.5% to −1.2%) standardised rate 120 v 133 (range +6 to +23) | Small improvement | No | No |

| New Life26 (1988 v 1998)All four target areas | % of working age registered unemployed or economically inactive | 58.5% v 53.2%, −5.3% (range −20% to +9%) | Improvement | Yes | |

| SRB32 (1996 v 1999)Panel survey in three target areas | % of working age population economically inactive | 29% v 25%, −4% (range −7% to −4%) England data 10% v 10% | Improvement | No | Yes |

| City challenge28 (1992 v 1994)14 of 31 target areas | unemployment rate (seven areas) | 21.9% v 21.6%, +0.3% (range −2.4% to +3.0%) | Unclear‐ mixed impacts | Yes | |

| SIP34 (1996 v 1999/2000)All nine target areas | unemployment rate (three areas) | 10.7% v 6.9% −3.8% (range −4.9% to −1.7%) Scotland data 1996 v 1999, −4.6% | Improvement | No | No |

| SRB30 (data collection over four years, dates not specified)Three target areas | unemployment rate (one area) | 15% v 4.2%, −10.8% England data 8.4% v 4.7%, −3.6% | Improvement | Yes | |

| Estate Action25 (1991 v 1997/98)Seven case study areas | % change in number of unemployment claimants over six years: in target area v local district | −29.5% (range −11% to −48%) v −36.9% (range −22% to −42.2%) | Improvement | No | No |

| SIP34 (1996 v 1999/2000)All nine target areas | % change in numbers of unemployment claimants (five areas) | −32% (range −44% to −17%) | Improvement | No | |

| Impacts on long term unemployment | |||||

| City challenge28 (1992 v 1994)14 of 31 target areas | % of unemployed who have been unemployed >12 months (five areas) | 40.9% v 42.8%, +2.9% (range −4.1% to +5.8) | Deteriorated | Yes | |

| SRB30 (data collection over four years, dates not specified)Three target areas | % of unemployed who have been unemployed >12 months (one area) | 40% v 23%, −17% England data 38% v 26%, −12% | Improvement | Yes | |

| SRB31 (1995 v 1997)Two target areas | % of unemployed + employed who are unemployed >12 months (one area) | 4.4% v 2.8%, −1.6% (range −2.3% to −1.3%), standardised rates compared with all England increased 129 v 167 (range +15 to +71) | Small improvement | No | No |

| Impacts on educational attainment | |||||

| New Life26 (1988 v 1994)All four target areas | pupils obtaining 1+ highers (two areas) | 12.5% v 15%, +2.5% (range +2% & +3%) | Improvement | No | |

| pupils obtaining 3+ standard grades (two areas) | 69% v 79%, +12% (range +4% & +16%) | Improvement | No | ||

| attendance rates at secondary school (two areas) | 74% v 82.5%, +11.5% (range +9% and +14%) | Improvement | No | ||

| City Challenge28 (1992 v 1994)14 of 31 target areas | pupils achieving >4 GCSEs grade A‐C | 16.3% v 20.8%, +4.5% (range +1.6% to +10.4%) | Improvement | No | |

| School leavers with no GCSEs | 14.8% v 14.2%, +0.6% (range −8.3% to +3.8%) | Unclear‐ mixed impacts | Yes | ||

| SRB30 (1994 v 1997)Three target areas | pupils achieving >4 GCSEs grade A‐C (one area) | 41.6% v 45.8%, +4.2% English data 43.3% v 45.1%, +1.8% | Improvement | Yes | |

| SRB31 (1994 v 1999)Two target areas | pupils achieving >4 GCSEs (one area) | 50.3% v 56.1% +5.8% (range +4.3% to +7.3%) | Improvement | No | |

| standardised rate where England = 100 (one area) | 116 v 117 (range −2 to +3) | Little or no improvement | Yes | No | |

| SRB32 (1996 v 1999)Panel survey in three target areas | any member of household with CSE/GCSE/O level | 53% v 54%, +1% (range −10% to +3%) | Small improvement | Yes | |

| taken part in training in past three years | 22% v 29%, +7% | Improvement | |||

| Impacts on household income | |||||

| New Life26 (1988 v 1994)All four target areas | households with incomes below £100/week | 65.3% v 48.8%, −16.5% (range −34% to +3%) | Improvement | Yes | |

| SRB32 (1996 v 1999)Panel survey in three target areas | households with incomes below £100/week | 30% v 26%, −4% (range −10% to −3%) England data 19% v 16%, −4% | Improvement | No | No |

| Impacts on housing quality and rent | |||||

| UDCs223 of 11 target areas | % of residents from local target areas now living in new/improved housing (two areas) | 42.5% | Improvement | ||

| Estateaction25 (1990/91 v 1997/98)Seven case study areas | Average weekly rent in LA housing 1990/1–1997/8 (areas) | +99.3% (range +8.9% to +324%) | Increased housing costs | No | |

| Average housing association weekly rent compared with previous local authority (four areas) | +116.8% (range +83.7% to +162.5%) | Increased housing costs | No | ||

*Where data provided in the evaluation report.

Data synthesis of direct impacts on health and socioeconomic status

Impacts on direct health and socioeconomic outcomes reported in the evaluations were self reported health status, mortality rates, employment (long term unemployment, employment, unemployment), household income, educational attainment, housing quality, and housing costs (rent) (table 2). A narrative synthesis of these impacts is presented below.

Impacts on self reported health and mortality rates

Impacts on self reported health or mortality rates were reported in three evaluations.26,31,32 In one evaluation that surveyed the same residents before and after the programme, three of four measures of self reported health deteriorated, typically by ±3.8%.32 Two other evaluations reported overall improvements in mortality rates (standardised mortality rate 131 v 11426 and 122 v 118,31 crude mortality rate −0.6%31) although standardised mortality rates increased in some case study areas in one of these evaluations.26

Impacts on employment and unemployment

Employment measures were the most frequently included outcome measure and data were reported in nine evaluations.18,25,26,27,28,30,31,32,34 Improvements were reported in all but one evaluation.18 However, this simple tally of positive impacts conceals the specifics of type of outcome assessed, negative effects, and missing data.

Three evaluations reported improvements in employment (% working age in employment +6%26 +4%32 and number of households with at least one person economically active +9%27), but in one of these evaluations employment rate fell in two of the four case study areas26 and in another evaluation there was no additional improvement when compared with the national trend in employment rates.32

Eight evaluations reported impacts on unemployment outcomes; in six of these positive impacts were reported (% unemployed −1.3%,31 unemployment rate −3.8%,34 −10.8%30 numbers of unemployment claimants −32%,34 −29.5%,25 and % working age economically inactive −5.3%,26 −4%,32). In two evaluations overall impact on employment outcomes were negative (unemployment rate +0.3%,28 % unemployed‐ +3.35%18). While improvements in unemployment measures were regularly reported, in two evaluations a mix of negative and positive impacts on unemployment measures were reported across case study areas26,28 and in a further three evaluations the improvements reported were similar to national or regional trends over the same time period.25,31,34

Impact on long term unemployment was reported in three evaluations (% of unemployed who have been unemployed >12 months,28,30 and % of (unemployed + employed population) who have been unemployed >12 months31). In two evaluations of the SRB long term unemployment fell (−1.6%31 and −17%30), although in one of these evaluations rates of long term unemployment increased relative to standardised English rates.31 In one evaluation of City Challenge an overall increase in long term unemployment was reported, although both increases and decreases were reported within individual case study areas (range −4.1% to +5.8%).28

Impacts on educational attainment

Five evaluations (1988–1999) reported impacts on school achievement. Improvements in proportions of “pupils obtaining >4 GCSEs” or “>2 standard grades” (Scotland) were consistently reported in the four evaluations that included this outcome (mean impact +6.25%).26,28,30,31 However, similar improvements in the proportion of “pupils obtaining >4 GCSEs” were also reported across England over this time and two evaluations reported little or no improvement when the findings were compared with national data.30,31 Despite overall improvements, both negative and positive impacts on the proportion of respondents reporting “any member of household with CSE/GCSE/O level”32 or “school leavers with no GCSEs”28 were reported across case study areas in two evaluations.

Impacts on household income

The number of households with incomes below £100 per week was assessed in two evaluations26,32 and an overall improvement was reported. However, in one of these evaluations a range of negative and positive impacts on this outcome were reported across the four case study areas (−34% to +3%).26

Impacts on housing quality and rent

The proportion of original residents living in improved housing after ABI investment was only reported in one evaluation (42.5%).22 Another evaluation assessed changes in housing costs; average social housing rent doubled over the period of investment, seven to eight years.25

Discussion

This review is a direct response to Wanless's call to tap “every opportunity to generate evidence from current policy and practice”.2 The use of conventional systematic review methods to synthesise impact data for both socioeconomic outcomes as well as health outcomes is a novel attempt to present evidence tailored to inform healthy public policy. The data synthesis suggests that previous ABIs may have small positive impacts (median size of positive impact reported ±5.5%, range 1.0% to 32.0%, for example, unemployment rate −3.8%,34 households with income of less than £100 −4%32) across a range of key socioeconomic determinants of health, although these impacts may mirror national trends. Small positive health impacts are also reported, but adverse health impacts remain a real possibility.

However, reports of impacts in the evaluations of ABIs are rare. In the UK, evaluation of ABI achievement has relied heavily on reports of gross outputs and monies spent (for example, number of new houses built), rather than reports of the actual impacts effected by the investment (for example, change in the proportion of residents living in poor quality housing). Even when an impact evaluation has been attempted this has often been unsuccessful. Evaluators frequently reported difficulties with data collection, preventing clear conclusions around impacts. This made identifying relevant evidence to synthesise for this review difficult. Common problems reported by evaluators included a lack of baseline data, lack of routine data that conform to target area boundaries, incomparable data between case study areas and a limited time scale in which to observe change in key outcomes.19,27,28,29,34,35,36,37 Data were often collected at an area level rather than an individual level, and panel surveys to assess impacts on the original residents before and after the ABI investment were used in only one evaluation.32 The potential, therefore, for this significant public investment to ameliorate deprivation and improve health and reduce inequalities remains unknown. Moreover, the possibility of adverse impacts of ABI investment on residents is also largely unknown.

What this paper adds

What is already known on this subject?

Strong links between socioeconomic circumstances and health are currently used to support large scale investment in national programmes of urban regeneration. Yet the potential for this investment to contribute to a health improvement strategy remains unknown. Evaluations of national urban regeneration programmes may harbour valuable data of the health and socioeconomic impacts of this large scale investment, but these data have not been systematically reviewed.

What does this study add?

Regeneration programmes may lead to some small positive impacts on health and socioeconomic circumstances, but adverse impacts are also a possibility. To date evaluations of national regeneration investment have rarely assessed impacts on health or impacts on the socioeconomic determinants of health; far less is reported on the social distribution of these impacts.

Impact evaluations that can be used to inform both public policy and healthy public policy are urgently required. In addition, innovative approaches to exploiting “best available evidence” can be used to inform the development of healthy public policy now.

Policy implications

Impact evaluations that can be used to inform both public policy and healthy public policy are urgently required. In addition, innovative approaches to exploiting “best available evidence” can be used to inform the development of healthy public policy now.

Implications for evidence based healthy public policy

The dearth of health impact data to inform the development of healthy public policy has already been established across a number of policy areas.13,38,39,40 In this review, the lack of socioeconomic impact data questions assumptions that ABI investment will reduce socioeconomic deprivation. In addition, the lack of data on both health impacts and socioeconomic impacts may undermine the rhetoric that links such investment to health gains and reductions in health inequalities.1,9,10,11,42,43 However, the absence of impact data does not provide grounds for inaction,8,41 and it would be wrong to conclude that there is no research evidence to support hypothetical links between ABI investment and health impact. For example, in the UK both the Black Report and the Acheson Report presented data from a wealth of cross sectional and longitudinal studies to establish clear links between socioeconomic circumstances and poor health.42,43

Improving the evidence base for healthy urban regeneration policy

Evaluations of ABIs need improving if they are to be used to inform the development of healthy public policy or to inform prospective health impact assessments of regeneration programmes. Detailed descriptions of variations in programme delivery and contextual factors that may account for variations in outcomes between areas are essential,44 and are already available in most ABI evaluations. In addition, evaluation of complex programmes, like ABIs, requires clear theories or hypotheses specifying pathways through which health and social outcomes might improve.45 To date these have been missing from both evaluations and programmes, even where health improvement is a key objective.

While health impact data remain on the public health “wish list”, “best available” evidence should be exploited.2 This will typically entail rigorous syntheses of socioeconomic impact data as a proxy for health impact data (the approach taken by this review). The extreme heterogeneity of interventions, contexts, methods, and outcomes is an inherent characteristic of this type of systematic review and synthesis will be methodologically challenging as well as producing findings that may often draw attention to uncertainty rather than offering tangible policy recommendations; however, establishing what is not known is essential to good practice.46 In the face of such uncertainty alternative sources of data can also provide evidence to direct policy and practice. Systematic reviews of cross sectional research evidence may help prioritise interventions and develop research informed theories for possible health impacts of policies which can then be tested through evaluation.

Conclusion

Despite significant public investment in national ABI programmes there is still little evidence to demonstrate the impacts on socioeconomic or health outcomes. Where impacts have been assessed, a small overall positive impact is suggested though adverse impacts are also possible. The few impacts reported rarely related to the original residents of target areas, thus the potential for ABI investment to improve the health or socioeconomic status of people or impact on inequalities remains uncertain.

Future evaluations need to incorporate clear theories of change informed by existing research evidence. In addition, an assessment of the actual impacts on original residents of target areas is required if the potential of such programmes to improve health and reduce health inequalities is to be confirmed. In the meantime, evidence syntheses that exploit best available data may be the best way to develop healthy public policy which is evidence informed.

A table giving details of specific health or social impacts included and reported in national evaluation is available on line (http://www.jech.com/supplemental).

Supplementary Material

Contributors

HT and RA were the principal reviewers, carrying out searches, screening, selection, and data extraction. HT and MP prepared the data synthesis. All authors contributed to planning the review and writing the paper. HT is the guarantor for this paper.

Footnotes

Funding: HT and MP are funded by the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Executive Health Department. The funding sources had no involvement in the substantive direction of this review. MP, RA, AK also received funding as part of the ESRC Evidence Network.

Competing interests: none declared.

Ethical approval: none required.

A table giving details of specific health or social impacts included and reported in national evaluation is available on line (http://www.jech.com/supplemental).

References

- 1.Department of Health Tackling health inequalities: summary of the 2002 cross cutting spending review. London: HM Treasury and Department of Health, 2002

- 2.Wanless D.Securing good health for the whole population. London: HM Treasury and Department of Health, HMSO, 2004

- 3.Cabinet Office Modernising government. London: Stationery Office, 1999

- 4.Mackenbach J P, Bakker M J, for the European Network on Interventions and Policies to Reduce Inequalities in Health Tackling socio‐economic inequalities in health: analysis of European experiences. Lancet 20033621409–1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackenbach J P, Stronks K. A strategy for tackling health inequalities in the Netherlands. BMJ 20023251029–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrne D. Enabling good health for all: a reflection process for a new EU health strategy. (European Commision for health and consumer protection) http://europa.eu.int/comm/health/ph_overview/Documents/byrne_reflection_en.pdf

- 7.Mackenbach J P. Tackling inequalities in health: the need for building a systematic evidence base. J Epidemiol Community Health 200357162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macintyre S, Petticrew M. Good intentions and received wisdom are not enough. J Epidemiol Community Health 200054802–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions Health and regeneration. London: Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions, 1996

- 10.Scottish Office Working together for a healthier Scotland. Edinburgh: The Stationery Office, 1998

- 11.Social Exclusion Unit A new commitment to neighbourhood renewal: national strategy action plan. London: HMSO, Social Exclusion Unit, The Cabinet Office, 2001

- 12.Elliott E, Landes R, Popay J.et alRegeneration and health: a selected review of research. London: Kings Fund, 2001

- 13.Thomson H, Petticrew M, Morrison D. Health effects of housing improvement: systematic review of intervention studies. BMJ 2001323187–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.CRD Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness: CRD's guidance for those carrying out or commissioning reviews. 2nd ed. York: CRD, 2001

- 15.Department of the Environment Evaluation of environmental projects funded under the Urban Programme. London: HMSO, 1986

- 16.JURUE An evaluation of industrial and commercial improvement Areas. Birmingham: ECOTEC Research and Consulting, 1984

- 17.Martin S. New jobs in the inner city: the employment impacts of projects assisted under the Urban Development Grant programme. Urban Studies 198926627–638. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baldock R O. Ten years of the Urban Programme 1981–91: the impact and implications of its assistance to small businesses. Urban Studies 1998352063–2083. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Department of Environment Transport and the Regions Urban development corporations: performance and good practice. London: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, 1998

- 20.Centre for Local Economic Strategies Interim monitoring report: urban development corporations. Manchester: Centre for Local Economic Strategies, 1989

- 21.Employment Committee The employment effects of urban development corporations. House of Commons session 1987–88, third report 1988

- 22.Deas I, Robson B, Bradford M. Re‐thinking the urban development corporation “experiment”: the case of Central Manchester, Leeds and Bristol. Progress in Planning 2000541–72. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Department of the Environment An evaluation of six early estate action schemes. London: HMSO, 1996

- 24.Department of the Environment The design improvement controlled experiment (DICE): an evaluation of the impact, costs and benefits of estate re‐modelling. London: Department of the Environment, 1997

- 25.Cole I, Shayer S, in association with the Northern Consortium of Housing Associations Beyond housing investment: regeneration, sustainability and the role of housing associations. Sheffield: Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research, Sheffield‐Hallam University, 1998

- 26.Cambridge Policy Consultants An evaluation of the new life for urban Scotland initiative in Castlemilk, Ferguslie Park, Wester Hailes and Whitfield. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive Central Research Unit, 1999

- 27.Pawson H, Munro M, Carley M.et alSmaller urban renewal initiatives (SURIs): an interim evaluation. Edinburgh: a report to Scottish Homes, 1998

- 28.Russell H, Dawson J, Garside P.et alCity Challenge interim national evaluation. Liverpool: Department of the Environment, European Institute for Urban Affairs, Liverpool John Moores University, 1996

- 29.Russell G, Johnston T, Pritchard J.et alFinal evaluation of City Challenge. London: KPMG Consulting commissioned by Department of the Environment Transport and the Regions, 2000

- 30.Brennan A, Rhodes J, Tyler P.Evaluation of the SRB challenge fund: first final evaluation of three SRB short duration case studies. Cambridge: Department of Land Economy, University of Cambridge, 1999

- 31.Brennan A, Rhodes J, Tyler P.Evaluation of the Single Regeneration Budget Challenge Fund: second final evaluation of two SRB short duration case studies (discussion paper 114). Cambridge: Department of Land Economy, University of Cambridge, 2000

- 32.Rhodes J, Tyler P, Brennan A.et alLessons and evaluation evidence from ten Single Regeneration Budget case studies: mid‐term report. London: Department for Transport, Local Government and the Regions, 2002

- 33.Rhodes J, Tyler P, Brennan A.et alEvaluation of the Single Regeneration Budget Challenge fund: summary of household survey results: 1996–199 (discussion paper 122). Cambridge: Department of Land Economy, University of Cambridge and MORI, 2002

- 34.Scottish Executive Central Research Unit National evaluation of the former regeneration programmes. Edinburgh: Central Research Unit, 2001

- 35.Johnston T, Russell G, Pritchard J.et alWhat works‐ learning the lessons: final evaluation of City Challenge. London: Department of the Environment Transport and the Regions, 1998

- 36.JURUE, Ecotec Consulting Birmingham Assessment of the employment effects of economic development projects funded under the Urban Programme. London: Department of the Environment Inner Cities Directorate, HMSO, 1986

- 37.Bourn J.The achievements of the second and third generation urban development corporations. London: HMSO, 1993

- 38.Morrison D S, Petticrew M, Thomson H. What are the most effective ways of improving population health through transport interventions? Evidence from systematic reviews. J Epidemiol Community Health 200357327–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Egan M, Petticrew M, Ogilvie D.et al New roads and human health: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2003931463–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Millward L, Kelly M, Nutbeam D.Public health intervention research: the evidence. London: Health Development Agency, 2001

- 41.Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S, Frankel S. How policy informs the evidence. BMJ 2001322184–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Acheson D.Independent inquiry into inequalities in health report. London: HMSO, 1998

- 43.Black D, Morris J, Smith C.et alInequalities in health: the Black Report and the Health Divide. London: Penguin Books, 1992

- 44.Rychetnik L, Frommer M, Hawe P.et al Criteria for evaluating evidence on public health interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 200256119–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pawson R, Tilley N. How to design a realistic evaluation. In: Realistic evaluation. London: Sage, 1997

- 46.Smith R. Nothingness: the role of journals. BMJ 2004328og. httpbmj.comcgicontentfull3287438og [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pinto R R. An analysis of the impact of estate action schemes. Local Government Studies 19931937–55. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scottish Office New life for urban Scotland. Edinburgh: HMSO, 1990

- 49.Neighbourhood Renewal Unit Evidence into practice: New Deal for Communities national evaluation. London: Department for Transport, Local Government and the Regions, 2002

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.