Abstract

Objective

To compare injury risk in elite football played on artificial turf compared with natural grass.

Design

Prospective two‐cohort study.

Setting

Male European elite football leagues.

Participants

290 players from 10 elite European clubs that had installed third‐generation artificial turf surfaces in 2003–4, and 202 players from the Swedish Premier League acting as a control group.

Main outcome measure

Injury incidence.

Results

The incidence of injury during training and match play did not differ between surfaces for the teams in the artificial turf cohort: 2.42 v 2.94 injuries/1000 training hours and 19.60 v 21.48 injuries/1000 match hours for artificial turf and grass respectively. The risk of ankle sprain was increased in matches on artificial turf compared with grass (4.83 v 2.66 injuries/1000 match hours; rate ratio 1.81, 95% confidence interval 1.00 to 3.28). No difference in injury severity was seen between surfaces. Compared with the control cohort who played home games on natural grass, teams in the artificial turf cohort had a lower injury incidence during match play (15.26 v 23.08 injuries/1000 match hours; rate ratio 0.66, 95% confidence interval 0.48 to 0.91).

Conclusions

No evidence of a greater risk of injury was found when football was played on artificial turf compared with natural grass. The higher incidence of ankle sprain on artificial turf warrants further attention, although this result should be interpreted with caution as the number of ankle sprains was low.

Keywords: injuries, football, surface properties, soccer, artificial turf

Grass is the traditional surface for football matches and training, but many regions in the world have a climate that makes development of adequate natural grass pitches difficult. Furthermore, modern specially designed football stadiums have a roof under which grass pitches do not thrive.

The use of artificial football pitches has been put forward as a solution to these problems.1 A comparison between first‐generation artificial turf and natural grass pitches revealed that the utility of artificial pitches was 12 times greater than grass pitches and the maintenance costs only 15%.2 However, playing football on first and second generation artificial turf has the disadvantage of a distorted bounce and roll of the ball and a there was concern that the risk of injury was greater. Renström et al2 reported results from a 2‐year study in Sweden in 1975 when the first artificial surface was introduced. They observed that football played on artificial turf in cleated boots increased the rate of injury. Engebretsen and Kase3 studied 16 teams over a 2‐year period in Norway in the 1980s. They found 30 injuries/1000 match hours on artificial turf compared with 20 injuries/1000 hours on grass; the difference was not statistically significant probably because of small numbers. Similar results were reported by Hort4 in the 1970s: more overuse injuries were found when football was played on artificial turf compared with natural grass. However, these two studies were too small for the results to reach statistical significance. In 1991, Árnason et al5 investigated the risk of injury in Icelandic elite football. They found a significantly higher injury risk on artificial turf than on natural grass (25 v 10 injuries/1000 hours of exposure, p<0.01). The relationship between artificial surfaces and a greater risk of injury, however, is poorly documented because the few studies reported have been small with methodological limitations.

The negative experience with first‐generation artificial surfaces led to the development of improved artificial turf especially designed for football with playing characteristics similar to natural grass. Third‐generation artificial turf pitches were introduced in the late 1990s, made of long (>40 mm) and much more widely spread fibres of polypropylene or polyethylene filled with rubber granules. The use of the term “football turf” instead of “artificial or synthetic turf of the 3rd generation” is the official terminology chosen by FIFA and UEFA for artificial turf most suitable for football based on test criteria identical with those of the best natural turf.

Positive preliminary experience from youth tournaments encouraged FIFA to allow international matches to be played on these new surfaces.6 However, no studies have evaluated injury risk when elite football is played on football turf. The aim of this study was to examine the injury risk associated with playing elite football on artificial turf compared with natural grass. On the basis of experience from studies on previous generation artificial turfs, our hypothesis was that injury risk is higher when football is played on artificial turf than when it is played on natural grass.

Methods

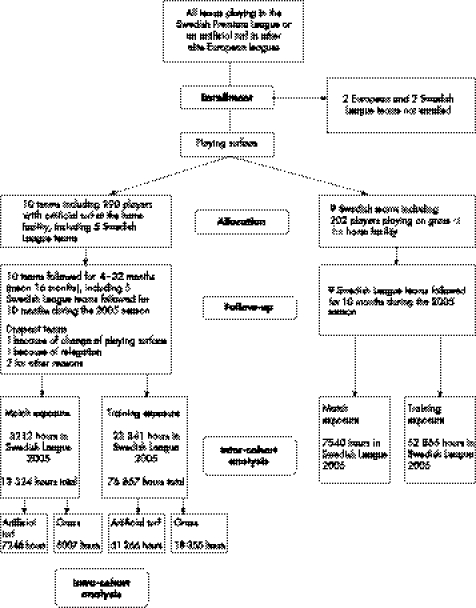

A prospective two‐cohort design was used for the study (fig 1). Male players from 10 elite European football clubs that had reported the installation of football turf (third‐generation artificial turf) to UEFA during the 2003–4 season constituted the study cohort. UEFA defines elite level as the two highest national football league divisions. Intra‐cohort differences in injury incidence on football turf and grass were used to assess the effect of the playing surface. To adjust for any home ground effect and to further evaluate the impact of the playing surface, the Swedish teams in the artificial turf cohort were also compared with a control cohort consisting of the players from Swedish Premier League clubs playing their home matches on grass.

Figure 1 Flow chart of the prospective two‐cohort study design and analysis.

Study period and subjects

The artificial turf cohort comprised 10 teams (290 players; mean (SD) age 25 (5) years (range 16–39)) who entered the study between February 2003 and January 2005. Two European clubs with artificial turf at their home ground were not included in the study, one because of language difficulties and the other because of lack of resources.

The control cohort comprised nine (202 players; mean (SD) age 24 (5) years (range 16–37)) of the 11 Swedish Premier League teams with grass at their home grounds; they delivered complete data during the 2005 season. One team declined participation because of lack of resources, and one team was unable to deliver complete data and was excluded.

All first team players who agreed to participate signed an informed consent form. Data from both cohorts were collected until November 2005. The clubs in the artificial turf cohort collected data over 4–32 months (mean (SD) 16 (9) months) (table 1), and all clubs in the control cohort participated over 10 months.

Table 1 Details of the 10 football teams who played on third‐generation artificial surfaces.

| Team | Study period | Time of data collection (months) | Country | League division* | Season | Type of artificial turf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Feb 2003–Oct 2005 | 32 | Sweden | 2nd | Spring–Autumn | Mondoturf |

| 2 | Jan 2004–Oct 2005 | 19 | Sweden | 2nd | Spring–Autumn | Saltex |

| 3 | Jul 2004–April 2005 | 8 | Sweden | 1st | Spring–Autumn | Fieldturf |

| 4 | Jan 2005–Oct 2005 | 10 | Sweden | 1st | Spring–Autumn | Limonja |

| 5 | Jan 2005–Oct 2005 | 10 | Sweden | 1st | Spring–Autumn | Fieldturf |

| 6 | Jan 2004–Oct 2005 | 20 | Finland | 1st | Spring–Autumn | Mondoturf |

| 7 | April 2004–Oct 2004 | 7 | Norway | 2nd | Spring–Autumn | Astroplay |

| 8 | Jan 2004–April 2004 | 4 | Austria | 1st | Autumn–Spring | Polytan |

| 9 | July 2003–Oct 2005 | 26 | Netherlands | 1st/2nd | Autumn–Spring | Arcadis |

| 10 | Oct 2003–May 2005 | 19 | Scotland | 1st | Autumn–Spring | XL turf |

*1st and 2nd divisions are the two highest domestic leagues.

Data collection included individual exposure and injury registration (by team medical staff) on standard forms. Data from players who left the study (because of transfer or other reasons) or clubs that left the study (one artificial turf cohort team dropped out because the playing surface at their home ground was changed, one team was relegated to a lower division, and two discontinued data collection for other reasons) before the end of the study in November 2005 were included in the analysis for the entire time of their participation.

Study procedure and validity

The development and validation of the protocols and methodology used in the present study have been described previously.7 The definitions and data collection procedures used follow the recommendations of the consensus statement for football injury studies.8

Player exposure and surface type were registered for all training sessions and matches (including matches with reserve teams) on a standard form by a member of the squad present at all training session and matches (same person throughout the study for each team). The team medical staff recorded all injuries on a standard form immediately after the event. All forms were sent to the study group on a monthly basis, and regular feedback was given to ensure complete records. All teams and contact persons were provided with a study manual describing all procedures related to injury and exposure registration to increase the reliability of the records.

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Linköping University, Sweden, and the whole study design was approved by FIFA and UEFA.

Definitions

A recordable injury was defined as an injury resulting from football training or match play leading to a player being unable to take full part in training or match play at any time after the injury. A player was considered injured until cleared by the team medical officer for full participation in team training and match play. Injuries were divided into four categories of severity according to the length of absence from training sessions and matches: slight (1–3 days); minor (4–7 days); moderate (8–28 days); severe (>28 days).

Training exposure was defined as any physical activity carried out under the supervision of the team coach. Match exposure for players participating included all matches (first, reserve and national teams) .

Analyses

The primary outcome measure was injury incidence (injuries/1000 hours of exposure) in training and match play. Secondary outcomes included injury severity and incidences of various injury types. In the intra‐cohort analysis, injury incidences in the artificial turf group were aggregated and compared between exposure on grass and artificial turf. In the inter‐cohort analysis, comparisons were made with the control group who played on natural grass. For this analysis, total exposure time and injuries during the same period (January to October 2005) for the five Swedish teams in the artificial turf cohort (table 1, teams 1–5) were used for comparison with the control cohort.

In addition, to adjust for a home ground effect, exposure and traumatic injuries sustained during home league matches during the 2005 season were analysed specifically. Injury incidences were compared between groups using rate ratios with 95% confidence intervals (rate ratio/exp(1.96 × standard error of log(rate ratio)) to rate ratio × exp(1.96 × standard error of log(rate ratio))).9 The significance level was set at p<0.05.

Results

Intra‐cohort analysis

Exposure

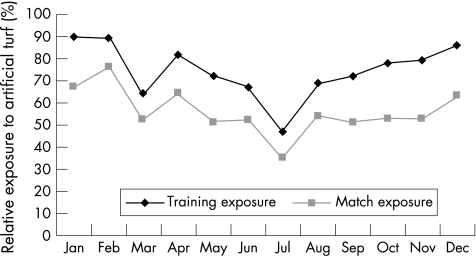

A total of 90 191 hours of football exposure were recorded during the study period in the artificial turf cohort; 65% of training and match exposure was on artificial turf, 27% on grass, and 8% on other surfaces (table 2). The relative exposure to artificial turf varied between teams, ranging from 47% to 81% (median 70%). As seen in fig 2, the relative exposure to artificial turf was highest at the beginning and end of the year for both training and matches.

Table 2 Exposure and injuries on different surfaces for the 10 teams playing at facilities with third‐generation artificial surfaces.

| Artificial turf | Grass | Other surface | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure (hours) | 58512 | 24362 | 7317 |

| Training | 51266 | 18355 | 7246 |

| Match play | 7246 | 6007 | 71 |

| Injuries (number) | 483 | 274 | 18 |

| Training | 301 | 100 | 12 |

| Match play | 182 | 174 | 6 |

Figure 2 Relative exposure to artificial turf and grass during the year.

Injury incidence and injury pattern

A total of 775 injuries was recorded, of which 455 (59%) were traumatic (5.04/1000 hours) and 320 (41%) overuse injuries (3.54/1000 hours). For the intra‐cohort analysis of injury incidence on artificial turf compared with natural grass, only traumatic injuries were included. This analysis showed no difference between surfaces in overall injury incidence during training or match play (table 3).

Table 3 Intra‐cohort analysis of injury incidence on artificial turf and grass.

| Artificial turf | Grass | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Incidence | No | Incidence | RR (95% CI) | |

| Training injuries (trauma) | |||||

| Total | 124 | 2.42 | 54 | 2.94 | 0.82 (0.60 to 1.13) |

| Slight | 38 | 0.74 | 20 | 1.09 | 0.68 (0.40 to 1.17) |

| Minor | 33 | 0.64 | 10 | 0.54 | 1.18 (0.58 to 2.40) |

| Moderate | 35 | 0.68 | 20 | 1.09 | 0.63 (0.36 to 1.09) |

| Severe | 18 | 0.35 | 4 | 0.22 | 1.61 (0.55 to 4.76) |

| Lower extremity | 115 | 2.24 | 48 | 2.62 | 0.86 (0.61 to 1.20) |

| Sprain | 48 | 0.94 | 12 | 0.65 | 1.43 (0.76 to 2.70) |

| Ankle sprain | 27 | 0.53 | 6 | 0.33 | 1.61 (0.67 to 3.90) |

| Knee sprain | 16 | 0.31 | 6 | 0.33 | 0.95 (0.37 to 2.44) |

| Strain | 32 | 0.62 | 24 | 1.31 | 0.48 (0.28 to 0.81)** |

| Hamstring strain | 14 | 0.27 | 8 | 0.44 | 0.63 (0.26 to 1.49) |

| Groin strain | 7 | 0.14 | 6 | 0.33 | 0.42 (0.14 to 1.24) |

| Match injuries (trauma) | |||||

| Total | 142 | 19.60 | 129 | 21.48 | 0.91 (0.72 to 1.16) |

| Slight | 36 | 4.97 | 35 | 5.83 | 0.85 (0.54 to 1.36) |

| Minor | 44 | 6.07 | 40 | 6.66 | 0.91 (0.59 to 1.40) |

| Moderate | 46 | 6.35 | 41 | 6.83 | 0.93 (0.61 to 1.42) |

| Severe | 16 | 2.21 | 13 | 2.16 | 1.02 (0.49 to 2.12) |

| Lower extremity | 128 | 17.66 | 107 | 17.82 | 0.99 (0.77 to 1.28) |

| Sprain | 51 | 7.04 | 34 | 5.66 | 1.24 (0.81 to 1.92) |

| Ankle sprain | 35 | 4.83 | 16 | 2.66 | 1.81 (1.00 to 3.28)* |

| Knee sprain | 15 | 2.07 | 16 | 2.66 | 0.78 (0.38 to 1.57) |

| Strain | 27 | 3.73 | 37 | 6.16 | 0.60 (0.37 to 0.99)* |

| Hamstring strain | 13 | 1.79 | 14 | 2.33 | 0.77 (0.36 to 1.64) |

| Groin strain | 6 | 0.82 | 9 | 1.50 | 0.55 (0.20 to 1.55) |

*p<0.05, **p<0.01.

RR, Rate ratio.

Ligament sprain (n = 151), contusion (n = 134) and muscle strain (n = 127) were the most common traumatic injury types. No abrasions or lacerations were recorded. The intra‐cohort analysis showed an increased risk of ankle sprain on artificial turf, reaching significant levels in match play (table 3). In contrast, the rate of lower extremity strains was lower on artificial turf (p<0.05) (table 3).

There was no difference in incidence of severe injuries between surfaces, although the tendency was that fewer severe injuries occurred on grass in training (table 3).

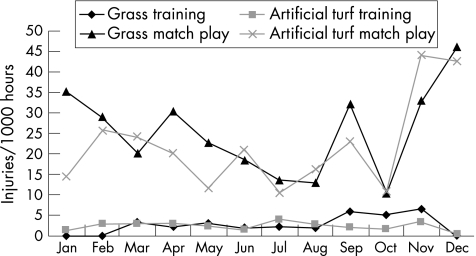

Figure 3 shows the rates of traumatic injury during match and training over the year. Match injury incidence was high at the beginning and end of the year, with another peak in September.

Figure 3 Distribution of traumatic injury incidence during the year.

Inter‐cohort analysis

The five Swedish teams in the artificial turf cohort registered a total of 26 553 hours of exposure (23 341 training, 3212 match play) and 177 injuries. In the control cohort, there were 60 406 hours of football exposure (52 866 training, 7540 match play) and 443 injuries recorded. The inter‐cohort comparison showed that teams in the artificial turf cohort had a lower match injury incidence than the control cohort (p<0.05), whereas the incidence during training was similar (table 4). When data were reduced to include exposure and traumatic injuries only during home league games, the incidence of injury was still lower for the artificial turf teams (p<0.01) (table 4). Compared with the control cohort, players in the artificial turf cohort had a lower incidence of lower extremity strains (p<0.01).

Table 4 Inter‐cohort analysis of injury incidence for teams playing on facilities with third‐generation artificial surfaces compared with control teams playing on natural grass at home.

| Artificial turf | Control | RR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Incidence | No | Incidence | ||

| Total injuries | |||||

| All injuries | 177 | 6.67 | 443 | 7.33 | 0.91 (0.76 to 1.08) |

| Primary | 149 | 5.61 | 377 | 6.24 | 0.90 (0.74 to 1.09) |

| Re‐injury† | 28 | 1.05 | 66 | 1.09 | 0.97 (0.62 to 1.50) |

| Overuse | 74 | 2.79 | 148 | 2.45 | 1.14 (0.86 to 1.50) |

| Primary | 60 | 2.26 | 115 | 1.90 | 1.19 (0.87 to 1.62) |

| Re‐injury† | 14 | 0.53 | 33 | 0.55 | 0.97 (0.52 to 1.80) |

| Trauma | 103 | 3.88 | 295 | 4.88 | 0.79 (0.63 to 0.99) |

| Primary | 89 | 3.35 | 262 | 4.34 | 0.77 (0.61 to 0.98)* |

| Re‐injury† | 14 | 0.53 | 33 | 0.55 | 0.97 (0.52 to 1.80) |

| Training injuries (trauma) | |||||

| Total | 54 | 2.31 | 121 | 2.29 | 1.01 (0.73 to 1.39) |

| Slight | 21 | 0.90 | 33 | 0.62 | 1.44 (0.83 to 2.49) |

| Minor | 11 | 0.47 | 34 | 0.64 | 0.73 (0.37 to 1.45) |

| Moderate | 14 | 0.60 | 40 | 0.76 | 0.79 (0.43 to 1.46) |

| Severe | 8 | 0.34 | 14 | 0.26 | 1.29 (0.54 to 3.09) |

| Lower extremity | 43 | 1.84 | 109 | 2.06 | 0.89 (0.63 to 1.27) |

| Sprain | 21 | 0.90 | 27 | 0.51 | 1.76 (0.99 to 3.12) |

| Ankle sprain | 10 | 0.43 | 18 | 0.34 | 1.26 (0.58 to 2.73) |

| Knee sprain | 8 | 0.34 | 9 | 0.17 | 2.01 (0.78 to 5.22) |

| Strain | 10 | 0.43 | 40 | 0.76 | 0.57 (0.28 to 1.13) |

| Hamstring strain | 5 | 0.21 | 13 | 0.25 | 0.87 (0.31 to 2.44) |

| Groin strain | 5 | 0.21 | 9 | 0.17 | 1.26 (0.42 to 3.75) |

| Match injuries (trauma) | |||||

| Total | 49 | 15.26 | 174 | 23.08 | 0.66 (0.48 to 0.91)* |

| Slight | 19 | 5.92 | 43 | 5.70 | 1.04 (0.60 to 1.78) |

| Minor | 8 | 2.49 | 51 | 6.76 | 0.37 (0.17 to 0.78)** |

| Moderate | 17 | 5.29 | 57 | 7.56 | 0.70 (0.41 to 1.20) |

| Severe | 5 | 1.56 | 23 | 3.05 | 0.51 (0.19 to 1.34) |

| Lower extremity | 39 | 12.14 | 150 | 19.89 | 0.61 (0.43 to 0.87)** |

| Sprain | 20 | 6.23 | 40 | 5.31 | 1.17 (0.67 to 2.01) |

| Ankle sprain | 11 | 3.42 | 26 | 3.45 | 0.99 (0.49 to 2.01) |

| Knee sprain | 9 | 2.80 | 14 | 1.86 | 1.51 (0.65 to 3.49) |

| Strain | 8 | 2.49 | 51 | 6.76 | 0.37 (0.17 to 0.78)** |

| Hamstring strain | 4 | 1.25 | 20 | 2.65 | 0.47 (0.16 to 1.37) |

| Groin strain | 2 | 0.62 | 18 | 2.39 | 0.26 (0.06 to 1.12) |

| Home league matches | |||||

| Exposure (h) | 868 | 1740 | |||

| Traumatic injuries | 8 | 9.21 | 48 | 27.59 | 0.33 (0.16 to 0.71)** |

*p<0.05; **p<0.01.

†Re‐injury of the same type and at the same site within 2 months of the final rehabilitation day of the index injury.

RR, Rate ratio.

Discussion

The strength of this study is that it is based on an injury recording system and a player sample specifically developed to address this issue. The recording of data followed the international consensus agreements on procedures for epidemiological studies of football injuries recommended by FIFA and UEFA.8 The only available data source on the injury risk associated with artificial turf for elite players is the few elite clubs already playing on artificial turf. We therefore contacted 12 elite European clubs that had installed third‐generation artificial turf surfaces in 2003–4 and invited them to participate in the study. Ten of these accepted and provided data. Nine of the 11 clubs in the Swedish Premier League that play on natural grass at their home stadiums acted as a control cohort.

The principal finding of this study was that both intra‐cohort and inter‐cohort analyses revealed that the injury incidence was similar when elite‐level football was played on either artificial turf or natural grass. The incidences of injury during training and match play found in the present study are comparable to the findings of other studies on elite football in Europe.10,11,12,13,14,15

The relative exposure to training and match play on artificial turf compared with natural grass was high in November to February, probably because of poor climate and grass pitch condition at that time of the year. The rate of traumatic match injuries was also high during these months, both on artificial turf and grass. This may imply that the rate ratio between injuries sustained on artificial turf and natural grass observed during matches in this study (0.91) may be somewhat overestimated. Had exposure on artificial turf and grass been more evenly distributed during these two months of the year when the risk of injury is high, the rate ratio would probably have been even lower. This would further support the conclusion that the overall risk of injury on artificial turf is no higher than on grass.

The only significant difference in injury pattern in this study was a higher risk of ankle sprain during matches on artificial turf and a lower risk of lower extremity muscle injuries. However, these differences in injury pattern should be interpreted with caution. Comparison of injury incidences between surfaces for specific injury sub‐groups is restricted by small numbers, and we must consider the possibility of type II error resulting from limited data. However, the tendency towards a lower rate of severe injuries on grass during training should be investigated further.

What is already known on this topic

Artificial turf pitches for football have advantages in terms of lower maintenance costs and a higher utilisation compared with natural grass pitches.

The first and second generation artificial surfaces have been associated with a higher risk of injury and changed injury pattern.

The injury risk on third‐generation artificial turf is not known.

What this study adds

This is the first study to evaluate the risk of injury in football played on third‐generation artificial turf pitches (football turf) compared with natural grass.

The data show no increase in injury incidence when elite football is played on artificial turf compared with natural grass.

From the medical point of view, there is no contraindication to expansion of artificial turf technology.

Previous studies evaluating injury patterns on the first two generations of artificial turf reported a higher incidence of overuse injuries.4 As a result one particular feature of third‐generation artificial surfaces is improved shock absorption. Even though a causal relationship between this intervention and a reduction in overuse injury is difficult to establish using our study design, the artificial turf cohort did not show a higher injury incidence than the control cohort. Similarly, the incidence of overuse injury in the artificial turf cohort is well in line with the overall incidence of overuse injury (2.6–5.6/1000 hours of exposure) found in previous studies on elite football in Europe using the same study design.13,14,15 Although not conclusive, this is an encouraging observation.

Wounds, burns and friction injuries have been reported to be more common on artificial turf.1,2,16 Injuries that did not result in absence from full training or matches were not included in this study, and we may therefore have underestimated this problem.

It is well known that the causes of football injury are multifactorial and there are many confounding risk factors to consider.17,18,19,20 One advantage of our intra‐cohort design was that the same teams were followed when they played their home matches on artificial turf, with most of their away matches being played on natural grass. This eliminated many of the confounding factors related to inter‐team differences—for example, variation in reporting and differences in climate. On the other hand, comparison with the control cohort allowed us to adjust for a home ground effect and evaluate the effect of playing surface on the rate of overuse injury. The study was limited by the fact that it was performed at a time when third‐generation artificial turf was allowed and progressively introduced for competitive matches at elite level. A number of different brands of artificial surfaces were included in the study and not all of these met the quality criteria subsequently drawn up by FIFA. Future studies would be better controlled if FIFA standardised testing is introduced universally. Furthermore, even though the study used the only data source available, the small database is still a limitation of the study, especially in sub‐group analysis.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the club doctors and contact persons for collection of exposure and injury data.

Footnotes

Funding: This research was funded by UEFA, the Swedish Sports Confederation (Sports Research Council) and Praktikertjänst AB.

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Ekstrand J, Nigg B M. Surface‐related injuries in soccer. Sports Med 1989856–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Renström P, Peterson L, Edberg B.Valhalla artificial pitch at Gothenburg 1975–1977, a two‐year evaluation. Sweden: Naturvårdsverket, 1977

- 3.Engebretsen L, Kase T. [Soccer injuries and artificial turf]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 19871072215–2217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hort W. Behandlung von schäden auf konststoffboden. BISP Köln 19779176–181. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Árnason Á, Gudmundsson Á, Dahl H A.et al Soccer injuries in Iceland. Scand J Med Sci Sports 1996640–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.FIFA Laws of the game. FIFA 2005

- 7.Hägglund M, Waldén M, Bahr R.et al Methods for epidemiological study of injuries to professional football players: developing the UEFA model. Br J Sports Med 200539340–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuller C W, Ekstrand J, Junge A.et al Consensus statement on injury definitions and data collection procedures in studies of football (soccer) injuries. Br J Sports Med 200640193–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirkwood B, Sterne J.Essential medical statistics. 2nd edn. Malden: Blackwell Science, 2003

- 10.Andersen T E, Tenga A, Engebretsen L.et al Video analysis of injuries and incidents in Norwegian professional football. Br J Sports Med 200438626–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ekstrand J, Waldén M, Hägglund M. A congested football calendar and the wellbeing of players: correlation between match exposure of European footballers before the World Cup 2002 and their injuries and performances during that World Cup. Br J Sports Med 200438493–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawkins R D, Fuller C W. A prospective epidemiological study of injuries in four English professional football clubs. Br J Sports Med 199933196–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hägglund M, Waldén M, Ekstrand J. Injury incidence and distribution in elite football: a prospective study of the Danish and the Swedish top divisions. Scand J Med Sci Sports 20051521–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walden M, Hagglund M, Ekstrand J. UEFA Champions League study: a prospective study of injuries in professional football during the 2001–2002 season. Br J Sports Med 200539542–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waldén M, Hägglund M, Ekstrand J. Injuries in Swedish elite football: a prospective study on injury definitions, risk for injury and injury pattern during 2001. Scand J Med Sci Sports 200515118–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaulrapp H, Siebert C, Rosemeyer B. [Injury and exertion patterns in football on artificial turf]. Sportverletz Sportschaden 199913102–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bahr R, Holme I. Risk factors for sports injuries: a methodological approach. Br J Sports Med 200337384–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ekstrand J, Karlsson J, Hodson A.Football medicine. London: Martin Dunitz (Taylor & Francis Group), 2003562

- 19.Mechelen Wv, Hlobil H, Kemper H Incidence,severity, aetiology and prevention of sports injuries. Sports Med 19921482–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meeuwisse W H. Assessing causation in sport injury: a multfactorial model. Clin J Sport Med 19944166–170. [Google Scholar]