Abstract

Only at the highest level of tennis is the number of winners comparable to the number of unforced errors. As the average player loses many more points due to unforced errors than due to winners by an opponent, if the rate of unforced errors can be reduced, it should lead to an increase in points won. This article shows how players can improve their game by understanding and applying the laws of physics to reduce the number of unforced errors.

Keywords: tennis, unforced errors

There are a number of ways in which a player's error rate can be reduced. Errors come about because the ball has hit the net, gone long (an error of depth), or gone wide (a lateral error). The first and second parts of this article discuss lateral and depth errors, and explain how spin and the speed of the hit can increase or decrease the likelihood of an error. The third part describes the theory behind the fastest serve and how players can increase their chances of hitting the serve into the service box. The final part focuses on the “sweet spots”—that is, where exactly on the racket head a player should hit the ball, with specific reference to the maximum power point. It explains how this sweet spot varies from shot to shot, and how players can use this to their advantage depending on the situation—for example, court surface, pace of shot, and use of the wrist.

Reducing lateral errors

Shots aimed straight down the middle of the court give quite a sizeable margin for error—almost 10° to the right or left before the ball lands in the alley. However, most players do not want to play safe and hit every shot down the middle. They want to be aggressive and go for the corners or down the sideline. They may want to (or have to) pass an opponent at the net. They may want to go for an occasional winner or at least make an opponent run for the ball once in a while. But this invites lateral errors.

Laws of physics

However, the number of errors from shots that go wide can be reduced even when players go for corners or sidelines if they remember a piece of critical advice: they should not change the ball angle! If a shot is coming cross court, they should return it cross court. If a shot is hit down the line, they should return it down the line. Changing the ball angle by attempting to return a cross court shot down the line, or return a down the line shot cross court is asking for problems with lateral errors. The reason lies in the physics of ball/racket interaction.

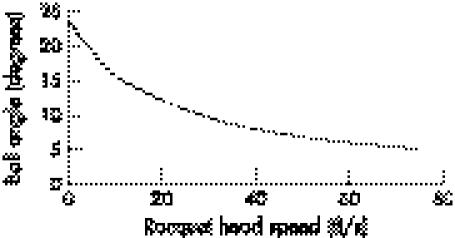

If a return does not change the ball angle, the ball's impact direction is perpendicular to the face of the racket at contact. The ball will then leave the racket in a direction perpendicular to the face of the racket. It will go out in the direction of the racket motion, whether the players swings hard, softly, or somewhere in between. However, this is not the case when a player tries to change the ball angle. The direction that the outgoing ball takes relative to the racket face then depends on how hard the racket is swung. The higher the relative ball/racket speed, the closer the ball will be to perpendicular to the racket face as it leaves the racket. This is illustrated in fig 1. If the swing is slow, the ball leaves the racket at a larger angle.

The same advice holds for the volley. With a hard return, the ball will go close to where it is aimed. However, if a player just tries to block the ball on a volley and is changing angles, the ball will slide off at a large angle, possibly going wide.

Changing angles

However, an opponent will quickly catch on if every shot is returned to where it came from. A player who knows the facts about ball/racket interaction can reduce the errors that may occur even when changing the ball angle. If the ball is not going to be hit hard, it should be aimed a little closer to the centre of the court. With a hard swing, the shot can be aimed closer to the sideline or the corner with confidence.

The famous statement that the angle of reflection equals the angle of incidence holds for light reflecting from a plane mirror, but not for tennis balls rebounding from a racket.

Often, in a match, players ease up when well ahead and do not hit shots quite so hard. This can reduce the errors of depth, but can also lead to a problem. If the ball is still aimed the same way, but the swing is no longer as hard, balls that previously went down the line may now end in the alley.

A similar problem can result from changing the game plan in the middle of a match. A player may become concerned about the final outcome, so instead of hitting out and playing his or her regular game, may decide to play it safer and ease up on the strokes. Again, balls that previously went down the line may now end in the alley. The player ends up making more, not fewer errors. People will claim that the player “choked”, but what actually happened is that they did not understand the laws of physics (fig 1).

Figure 1 Ball angle as it leaves the racket versus racket head speed for an incident ball at 20° and 60 ft/s.

Reducing errors of depth

For a groundstroke to be good, it must clear the net and yet not land beyond the baseline. For a given set of initial conditions (ball speed, hitting height, spin, etc), there is a minimum angle for the ball trajectory off of the strings that will just clear the net. For the same initial conditions, there is also a maximum ball angle off of the strings that will allow the ball to land within the court. To be a “good” shot, a ball must be launched between these two angles, and the difference (maximum angle minus minimum angle) is defined as the vertical angular acceptance or the angular window of acceptance. The larger this acceptance window, the more likely it is for a shot to be good and the less likely it will end up being an error. The size of this acceptance window depends on how hard the ball is hit, how much spin is put on it, the location of the player on the court, and how high above the ground the ball/racket impact takes place. If this window is large compared with the player's variation in vertical angle from shot to shot, the player will be “steady”. If this window is small or comparable to the shot to shot angular variation, the player will make lots of errors.

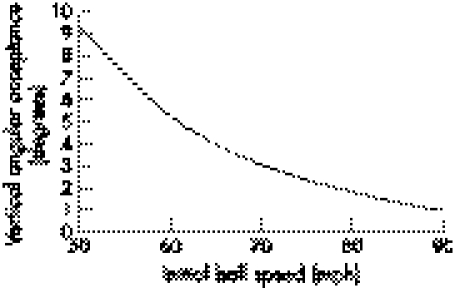

A computer program has been written that calculates the window size as the initial conditions that are under the control of the player are varied, such as ball speed and spin. Figure 2 shows how the angular window for a flat (no spin) groundstroke varies with initial ball speed if all the other variables are held constant. From these data, it is clear that the harder the ball is hit, the smaller is the window through which the ball must go in order to be a good shot. This is independent of the fact that the shot to shot variation in angle may increase as the racket head speed is increased (some players tend to lose some racket head control when they attempt to hit the ball harder).

Figure 2 Angular window versus ball speed.

Ball speed

Figure 2 shows that, as the incident ball speed is increased from 50 to 60 mph (which is from 80 to 96 km/h), the acceptance window shrinks by 43%. If the ball is hit even harder increasing the speed to 70 mph (112 km/h), the window decreases until it is only one third of its original size. This is because the only force that makes a flat (no spin) shot land in the court is gravity. When the ball is hit hard, gravity has less time to pull it down into the court and also the ball has greater resistance to being pulled down. No wonder it is difficult to get those hard shots to land in the court. The player is fighting against both geometry and Sir Isaac Newton, as well as the opponent! What should the player do?

Some players want to hit the ball hard and it is more important to them to do so than to lose points through making errors. There is no advice for them, because they will not heed it. Other players just want to win. This second type of player should reduce their ball speed and by doing so reduce their errors of depth. By how much should they reduce their racket head speed and their ball speed? As fig 2 shows, the window keeps increasing as the ball speed decreases. However, when the window is considerably larger than the “spray” (the variation in vertical angle from shot to shot) and the player is making very few errors of depth, they no longer need to slow their shots down. Hitting harder does have the advantage that it may cause the opponent to make more errors.

Spin

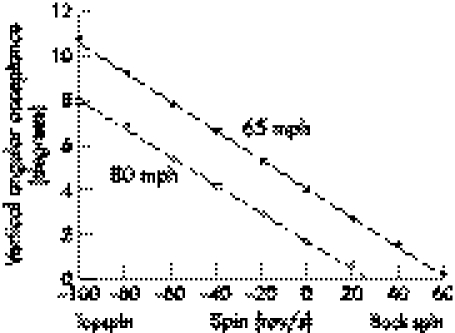

What else can players do to open up their acceptance window, besides not hitting the ball as hard? Hitting the ball when it is higher in its trajectory will increase the window size, but the most effective way is to add topspin, if the shot can be controlled. Figure 3 shows how the acceptance window depends on the spin of the ball. Topspin acts like an additional downward force, helping gravity to pull the ball into the court. The more topspin the ball has, the greater the downward force (called the Magnus force) and the bigger the window.

Figure 3 Vertical acceptance window versus spin for 65 and 80 mph groundstrokes.

If topspin is such a great thing, why does everyone not hit with lots of topspin and why are beginners not taught to hit that way? When you work out the physics of applying topspin to groundstrokes, you discover that a player must swing the racket much harder to achieve topspin than for a flat shot and twice as hard as for a sliced shot. This is because the ball is being hit after it has bounced, and, because of the bounce, the ball acquires a great deal of topspin before it reaches the player. For players to hit with their own topspin, they must not only turn the ball's direction around, but also completely reverse its spin direction. This is why a much higher racket head speed is needed to hit with topspin. For many players, this higher racket head speed is not possible or they lose control of the racket head when they try to do it. So they end up hitting flat strokes or even chopping at the ball, which requires the least racket head speed and the least racket preparation.

The 149 mph (240 km/h) serve

The present world record for serve speed (149 mph or 240 km/h) is held by Rusedski and recently Roddick. Is there an upper limit set by physics and geometry on how fast a serve can be? No! For any player six foot (1.83 m) tall or taller, there is no limit on serve speed set by physics and the geometry of the tennis court.

Bruce Elliott has shown that tennis players hit their serve at a height that is one and a half times their actual height. On this basis, a six foot tall player will strike the ball at a height of nine feet. Rusedski, who is six foot four inches tall, hits the ball at a height of nine feet six inches above the ground. If you take a straight line from the service line and just skim the top of the net, it will cross the plane of the baseline at a height of eight feet nine inches. This means that any player hitting the ball at that height (or higher) does not need gravity to pull the ball down into the service box. Does that mean that it does not matter how tall you are as long as you are over six feet tall? No! Does that mean it is as easy to get in a 149 mph serve as a 100 mph serve? No! Let us examine the effect of gravity and geometry on the ability of a player to make the serve go in.

Firstly, let us look at the groundstroke. A typical groundstroke is hit from the baseline at a height of three feet and must clear a three foot high net. If there were no gravity, the ball would sail over the opposite baseline at a height of three feet (it would travel in a straight line). Air resistance will not make the ball's path deviate from a straight line. Turn on gravity and it will pull the ball into the court. The more time gravity has to work on the ball, the shorter the bounce will be. If the ball is hit hard, gravity has less time to affect the ball, and it will bounce deeper in the court or go long.

The same argument holds for the serve. Even though a serve, for a tall player, can land in the service box without gravity, turning gravity on will make it easier to get the ball to bounce within the box. Hitting the ball hard reduces the time gravity has to act and makes it more difficult to get the serve to go in. The higher the ball is when hit, the more of the service box is available for the ball to land in, just from geometry. So hitting the serve from a higher impact point and not hitting it as hard will increase the chances of the serve being good.

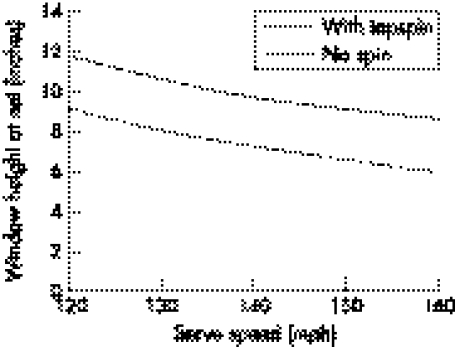

You can think of this in terms of a window at the net (it is called the acceptance window). A player must make the ball go through a certain window if the serve is to be good. The higher the ball impact location, the bigger the window. The higher the ball speed, the smaller the window. Players cannot do much about the height of the ball impact, except be fully extended when they strike the ball. However, no amount of practice will change their own physical dimensions. Players also want to hit their serves hard to make them difficult to return, yet they want to make most of them good. What can they do to get more serves in? Add some topspin. Topspin opens the window by providing an additional downward force (the Magnus force) on the ball. It is as if gravity were increased.

To put topspin on a serve, the racket usually must be moving upward as well as forward at the instant of impact. However, if the racket is moving upward at impact, the server is not hitting the ball at full extension. The topspin will enlarge the window, whereas hitting below full extension will close the window a little, usually leaving a net increase in the acceptance window, which means more serves will go in. Putting topspin on the serve is not as easy to achieve on the court as it is to talk about here, but there is a way around this problem.

Many players hit their serve when the ball they have tossed up reaches its peak. If instead, the player tosses the ball up about 8 inches (20 cm) above the eventual impact point and hits the ball as it is falling, topspin is automatically added to the ball, with no additional effort by the server. It would not be a lot of topspin (about 10 rev/s), but enough to open up the window and allow more serves to go in. If the player is already hitting the ball at a height of 9 feet or more and not hitting it very hard (about 120 mph or 193 km/h), this extra spin will open the window by about 29% as the window is already large (fig 4). If the player tries to hit the serve very hard (150 mph) and succeeds, the acceptance window will be small, but the 10 rev/s of topspin will help to get an extra 41% of the serves in.

Figure 4 Height of acceptance window at the net versus serve speed as it leaves the racket for a shot hit from a height of 9 feet with no spin and with 10 rev/s topspin.

Getting back to the 149 mph serve. How much better is it than a 120 mph serve, assuming that it can be made to go in? It takes a 120 mph serve 0.59 second to go from the racket, through the bounce, and to the opposite baseline. It takes a 149 mph serve 0.47 second for the same trip. This is a difference of 0.12 second, or about one eighth of a second. Whereas a player may have some chance of returning a 120 mph serve (if it is hit near him/her), take away one eighth of a second from the 120 mph time and it is unlikely that it will be returned, unless a correct guess is taken as to where it will be going.

Where on the head should a player hit the ball?

There are three sweet spots on a racket—that is, locations where it feels good to hit the ball. They are the node (minimum vibration point), the centre of percussion (minimum shock or jar point), and the maximum power point (highest ball rebound speed). The location of the node and centre of percussion points of the racket are fixed by the physical parameters of the frame (length, balance, moment of inertia, flexibility, etc). They are located near the centre of the strung area and are usually very close to each other, so if you hit one, you generally hit the other. The maximum power point location is also determined by these same physical parameters and in addition, the style of the stroke and the incoming ball speed. Where the location of the node and centre of percussion can easily be determined in the laboratory (see chapter 6 of The physics and technology of tennis by Howard Brody, Rod Cross, and Crawford Lindsey, RacquetTech Publishers, (an imprint of the USRSA) 2002, Solana Beach, CA. www.racquettech.com), the location of the maximum power point can, and does, vary from shot to shot and player to player. This section describes how the location of the maximum power point is found, why it varies in position from shot to shot, and where on the racket head certain balls thus should be hit.

When rackets are tested for power in the laboratory, balls are fired at a freely suspended racket at rest, and the ratio of ball rebound speed to incident ball speed is determined for various impact points on the head. This ratio (Vrebound/Vincident) is called the apparent coefficient of restitution (ACOR). The term “apparent” is used because the recoil speed of the racket is neglected. The value of the ACOR tends to maximise near the balance point (centre of mass) of the racket and falls off as the ball impact location moves away from balance point toward the tip. The reason for this variation comes from the basic physics of the interaction. When a ball impacts at the centre of mass, no energy goes into racket rotation, as the racket just recoils and does not rotate. The further the ball impact point is from the centre of mass, the greater is the impulsive torque tending to rotate the racket about its centre. As more energy goes into racket rotation, less goes into the ball's rebound, so the ACOR decreases. For a free racket at rest, this leads to lower values of ACOR as the impact point moves away from the balance point and toward the tip of the frame.

If, when a player swings at the ball, the racket is translated (straight line motion only), the maximum ACOR point would be the maximum power location because all points in the racket are moving with the same speed. However, a racket is swung in an arc, not translated in a straight line, so the tip has a higher velocity than the throat. This moves the location of the maximum power point higher up on the head. There is a simple formula for determining the rebounding ball speed if the racket head speed, ACOR, and incoming ball speed are known:

V(hit ball) = ACOR × V(incident ball) + (1 + ACOR) × V(racket)

where V(hit ball) is the rebounding ball speed, V(incident ball) is the incoming ball speed, and V(racket) is the speed of the racket head at the ball impact point.

The variation with respect to location of the racket head speed depends on the nature of the swing (is it “wristy”, etc?). The ACOR also varies with location and depends somewhat on the racket construction. As the formula shows, the ball rebound speed also depends on the incoming ball speed and the racket head speed. A swing that uses a great deal of wrist action will have a much greater racket speed near the tip than near the throat. This will move the maximum power location higher up in the head. Note that the incoming ball speed is multiplied by ACOR, whereas the factor multiplying the racket head speed is (1 + ACOR). As the values of ACOR run from about 0.1 to 0.5, the (1 + ACOR) term does not depend too strongly on the value of ACOR. This effect moves the location of the maximum power point down toward the throat (maximum ACOR location) as the incoming ball speed increases or as the racket head speed decreases. As the incoming ball speed decreases or the racket head speed increases, the maximum power point location moves upward toward the tip.

The limit of all of these factors is the serve, with a swing having a great deal of wrist action, no incoming ball speed, and a large racket head speed. For a typical serve, the maximum power point is up toward the tip of the racket, well above the centre of the head. This extra height above the ground for the ball impact location not only results in higher serve speeds, but also increases the window of acceptance for the serve—that is, the chance that it will go in.

What is already known on this topic

Most of the information available on error reduction in tennis is anecdotal

The advice given ranges from “Don't hit the ball so hard” to “concentrate” to “practice more”

What this study adds

On the basis of computer generated ball trajectories and the physics of ball/racket interaction, specific advice is given on how to reduce errors in tennis shots

Conclusion

Players can reduce the number of errors if they keep the laws of physics in mind.

The first is not to change the ball angle. If a shot is coming cross court, it should be returned cross court. If a shot is hit down the line, it should be returned down the line. Changing the ball angle by attempting to return a cross court shot down the line, or return a down the line shot cross court is asking for problems with lateral errors.

The second piece of advice is to reduce ball speed in order to reduce errors of depth. How much depends on the variation in the shots. If the acceptance window is larger than the spray and very few errors of depth are being made, there is no need for players to slow their shots down any more.

Thirdly, to hit the serve hard to make it difficult to return, but also to get most of them in, some topspin should be added. A way to do this is to toss the ball up about 8 inches (20 cm) above the eventual impact point and hit it as it is falling; topspin is automatically added to the ball, with no additional effort by the server.

Finally, players should try to hit groundstrokes closer to their hand on fast courts (grass, etc) and when their opponent hits a hard shot. They should try to hit shots further out on the racket when playing on slow (clay) courts or against an opponent who hits a soft shot. When they really crank up and try to blast shots, they should aim to hit the ball a bit higher on the racket head. The more wrist used in the stroke, the further out on the head the player should hit the ball.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none declared