Abstract

In 2002, Tennis Australia commissioned a report into the experiences of elite female past players on leaving the professional tennis circuit. Australian players who were in the top 800 of the Women's Tennis Association (WTA) end of year rankings and who had left the professional circuit within the previous 15 years were asked by mail to respond to a questionnaire. The questionnaire asked players to describe their feelings about leaving the tour during the time leading up to leaving the tour to two years after retirement. The main findings of the study suggested that those who planned to leave the tour found the transition process easy, whereas those who did not plan to leave the tour found the process difficult. Most players (66%) did not regret leaving the tour, and, although the remaining players responded that they regretted leaving, none attempted a comeback. Tennis Australia has implemented strategies to assist current players on the professional tour based on the results of this study.

Keywords: tennis, retirement, career transitions, life span development, female athletes

The transition of tennis from an amateur to a professional sport began in the late 1960s, and it continues to become more professional with increasing numbers of tournaments, prize money, and numbers of young players aspiring to become full time. For these athletes, focusing on their elite tennis career is often an all consuming task. They forego education (secondary schooling) and work opportunities and reduce social networks (friends and extended family) to concentrate on tennis training and competition. The single mindedness of professional tennis players is such that they may be taken unawares and be under‐prepared when it comes to retiring from competitive tennis. Whereas in the not too distant past tennis players were most likely to be earning their main income externally to their sporting endeavours, current tennis players are more likely to be financially, and consequently socially, estranged from “the real world” in their attempts to make a full time living from tennis.

It is well established in the area of career transition/retirement from elite sport that athletes are confronted with a wide range of psychological, interpersonal, and financial adjustments when they end their competitive careers.1 Moving away from the gerontological (which likens retirement from sport to retirement from the workplace)2 and thanatological (which likens sports retirement to a form of social death)4 models, many researchers4,5 are currently adopting “transition models” to explore the transition process (where transition is usually defined as “discontinuity in a person's life space”; p 122 of Crook and Robertson6). For example, in Schlossberg's7,8 transition model, three factors interact during a transition: (a) characteristics of the transition—that is, the trigger, timing, source, and duration of the transition; (b) characteristics of the individual—for example, sex, role, age; (c) characteristics of the environment—for example, social support networks.

As some studies have suggested, retirement from sport may be traumatic,9 and athletes must adapt to the ordeal of career termination.10,11,12,13 Conversely, other studies have indicated that athletic retirement may not be traumatic, but rather an important event that influences the retiring athletes' wellbeing and development.14,15,16 Linked to these two schools of thought is whether the retirement from sport was voluntary/planned—that is, under the athlete's own terms—or involuntary/unplanned—where the athlete has had no option because of injury or de‐selection, or has not dealt with the issue while still an athlete. Although questioned,17 it has been well described12,14,18 that voluntary retirement is a positive adjustment factor19 associated with fewer difficulties and greater emotional and social adjustment after retirement. Conversely, involuntary retirement is a negative adjustment factor19 associated with difficulties such as emotional tension and distress20 and increased feelings of anger, failure, and loss.21

Tennis is predominantly an individual sport, and apart from the Fed Cup or Davis Cup where players are selected to represent their country, players, in the main, are not reliant on selection by their national sporting organisation (NSO) to play at international levels. Currently, players participating in professional tournaments enter through the International Tennis Federation and bypass the NSO completely; therefore players generally travel the world as individuals (sometimes supported by a coach, travelling companion, fitness advisor, and/or significant others). Higher ranked national players may be selected to compete as part of a team environment—for example, Fed Cup—for a couple of weeks a year until retirement. Because of the highly individual nature of international tennis, the issues of retirement are not well understood. This is due to the difficulty of keeping track of players (particularly lower ranked players) and locating them once they have retired and re‐entered “normal life”.22

Despite the vast pool of literature on retirement from sport, surprisingly, there is little research on retirement experiences of professional tennis players. In the only known study published on retirement from tennis, Allison and Meyer,22 using a questionnaire approach, surveyed 20 tennis players who had played on the professional tour. The results indicated that the initial response of the athletes was frustration and anxiety, but overall they did not find retirement traumatic. Rather, retirement was a positive experience, with those surveyed perceiving it as an opportunity to re‐establish more traditional societal roles and lifestyles.

In response to concerns about the transition from the professional tour for Australian female players, Tennis Australia commissioned a study into the experiences of elite, internationally ranked players leaving the professional tennis circuit. The study also explored what Tennis Australia, as the NSO, could or should do, if anything, to assist in the career transition of players. A qualitative investigation was planned, so that players could answer a standardised set of questions, with many responses left open for the players' own perceptions and insights to be included. A preliminary report of this work has been presented.23

Method

Approval of the study, conforming to the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki), was granted by the Board of Management, Tennis Australia. The mailing addresses of 82 former elite Australian players were obtained from the Women's Tennis Department. Players were sent a questionnaire accompanied by a covering letter detailing the general purpose of the study and how to respond to the questionnaire. A reply paid envelope was included for returning of the questionnaire. Participants were free to choose to respond or not to the questionnaire. Completed questionnaires were returned by 28 tennis players (34%) and were used in the data analysis. Two uncompleted questionnaires were returned as the potential participants were overseas and felt unable to contribute.

Participants

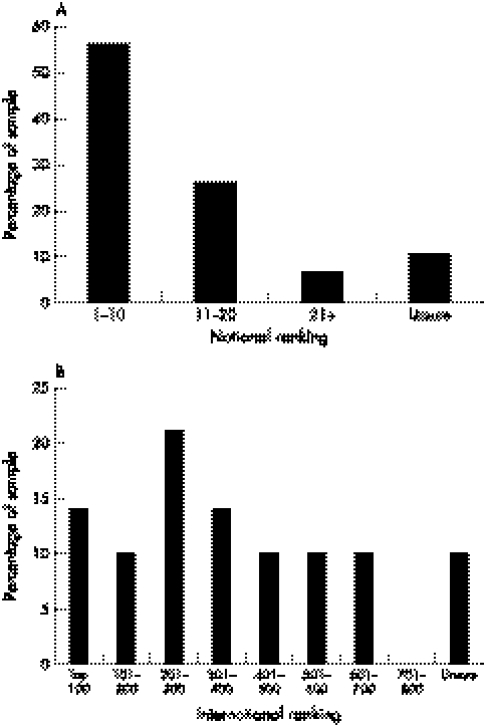

Participants were former elite female Australian tennis players who achieved a top 800 or better in the Women's Tennis Association (WTA) end of year international rankings (mean ranking 320, range 45–700). Figure 1 shows the breakdown of national (Australian) and international rankings. The players in this sample had been retired at the time of data analysis for mean (SD) 6.6 (3.6) years (range 1–15), and had played for 5.7 (3.5) years (range 1–10) on the professional circuit.

Figure 1 Breakdown of national (A) and international (B) rankings of participants in study.

Instrument

The questionnaire was developed by three of the investigators in response to the specific areas of interest defined by Tennis Australia. The eight page questionnaire consisted of both closed and open ended items (29 in total). In addition to a series of demographic questions, the questionnaire asked players to recount (a) factors contributing to their decision to retire, (b) their feelings and emotions before and after leaving the circuit, and (c) how Tennis Australia could have assisted them more in the transition. Therefore the questionnaire provided face validity and was consistent with that developed by Alison and Meyer22 in asking participants to recount their reactions to retirement from the tour.

Data analysis and presentation

Descriptive data are reported, where appropriate, as mean (SD) (range) or as a percentage of the sample. Qualitative data were content analysed, where possible, for key themes and phrases, or reported verbatim in the words of the subjects.

Results

Current tennis involvement

A high percentage of the respondents (88%) reported that they were still involved in tennis: playing (14%); coaching (28%); coaching and playing (25%); coaching, playing, and managing national or state junior tennis teams (14%); tennis administration (7%). Just over half the sample (52%) was satisfied with their current amount of tennis involvement. However, 45% responded that they were not, and one person (3%) was “somewhat satisfied”. Those not satisfied were asked to nominate areas in which they would like to work. Many preferred to coach players of a “higher standard”, to work in the media, to take on a team manager role, or work in tennis administration at state and/or national level.

The level of tennis related involvement was expected to increase in the near future for 24% of the sample or in the distant future for 40%, but some expected it to decrease in the near (4%) or distant (4%) future, and 28% were unsure how their involvement might change. Issues that prevented a former player from increasing their involvement in tennis related activities included “no interest at that stage” (16%), “was pursuing other opportunities” (16%), “having children” (16%), and “didn't know how to get involved/not told about alternatives/felt it was a closed shop” (50%).

Other sport involvement

Just over half the sample (55%) was not involved with other sports. Of those who were, 83% nominated team sports (such as hockey, netball, touch football), whereas the remaining 17% pursued individual sports (running, golf). Reasons for participation in other sports included “team atmosphere” (36%), “enjoyment” (9%), “exercise” (9%), “using coaching skills other than tennis” (9%), “having no expectations about my performance” (18%), “because I'm past my prime in tennis” (9%), and “it's part of my teaching job” (9%).

Leaving the tennis circuit

When it came to leaving the professional circuit, 62% of the sample had been thinking about leaving the circuit before their departure, and their planning usually involved two or more of the following strategies: speaking with the coach, other competitive players, or significant others; reading books about the process of retiring from sport; making other plans—for example, having a family or enrolling at university. Of the remainder of the sample, 24% cited that they did not do much planning, and 14% left the tour because of an unexpected injury.

Process of leaving the tour

As illustrated in table 1, many reasons were typically given for the players' actual departure from the professional circuit. Sixty per cent of the sample claimed that they had made plans or were in the process of making plans to leave the professional tour, with the remaining 40% indicating that they left the tour unplanned (28%) or were forced out through injury (12%). Over half the sample (56%) claimed that they found the transition process easy, with the remainder finding the process difficult.

Table 1 Responses of players on factors contributing to their departure from the circuit.

| • I didn't feel like I had the commitment and dedication to further my career and wanted to pursue another career outside of being a professional athlete (2) |

| • I basically wanted to start another career and learn outside of the tennis world. Knew of the commitment level needed to continue and improve and didn't feel it would be that rewarding. Loss of hunger (4) |

| • I had been accepted into medicine at University and I had deferred a year to continue playing on the circuit. When I found that I was “burning out” and psychologically lacked confidence, I began behaving self destructively (eg believing I'd lost a match before it had even started). I knew I had a “soft option” despite at the time having little interest in medicine (16) |

| • I forgot what it was like to win/couldn't win; lost my passion to be a pro; didn't enjoy the relationship between other girls (superficial) (21) |

| • Travelling with no support for months on end did not help with my tennis. Other players, especially Australians, do not work together for each others' (or the Australian coaches') benefit. Financial issues…(are)…a major one because it is difficult to keep going…(when always)…only travelling on the Satellites, and the next step is difficult to take without support (23) |

| • I played for 10 years and basically I had had enough of being in the tennis world. I lost my competitive edge and wanted to have other experiences. Maybe if I'd scheduled a big break somewhere in my career I may have lasted longer…but I was never injured and had financial obligations so I didn't consider it (27) |

| • (I)…had basically 9 months off with a foot operation, so…(I)…had to basically start (ranking wise) at 200 again, and I wasn't prepared to go back and start over again (32) |

| • (I)…fell ill after the last 3 months of tournaments in Asia where I did well. I felt I wanted a change after training so hard to be in peak condition and not being able to play. It took 6 months to feel well again and I decided to move on to other things in life (e.g. family, new personal development skills and normal life at home) (37) |

| • Having traveled all by myself… (I found that)…trying to organise all aspects of the circuit was very difficult. More support would've made the circuit less stressful and having female support would have been appreciated (either a past player or a coach to give advice…(based on)…their experiences of the circuit (38) |

| • (I)…had to make a decision between work or tennis. (I)…probably didn't have enough belief in myself that I could overcome bulimia and keep playing on circuit. I tried to combine both playing and coaching (apprentice coach at AIS at 22) but it did not work (45) |

| • Injury, not enough support to keep going, financially and psychologically stale once injured…(which)…caused a drop in ranking, thus couldn't stay positive and stay focused, hence…(I)…quit (63) |

| • (I)…had to decide between study or tennis – (I)…couldn't do both. (I)…found the circuit and women extremely ‘bitchy' (awful environment). I was not tough enough (82) |

Subject identification in parentheses.

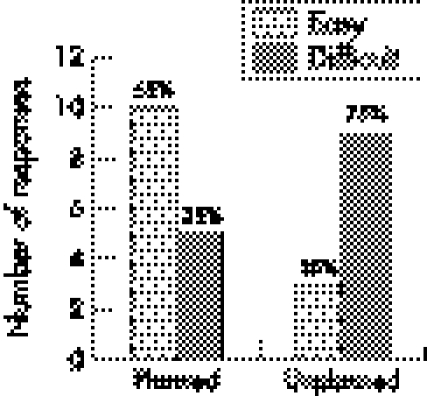

Figure 2 shows associations in the sample between planned and unplanned retirement by easy or difficult transition. Of those who planned to leave the tour, 65% reported an easy transition. Conversely, 75% of those who indicated that their decision was unplanned found the process difficult. All who left the tour because of unexpected injury (and hence were forced out) found the process of leaving the tour easy.

Figure 2 Transition experiences of players leaving the tour.

Regrets and feelings about leaving the tour

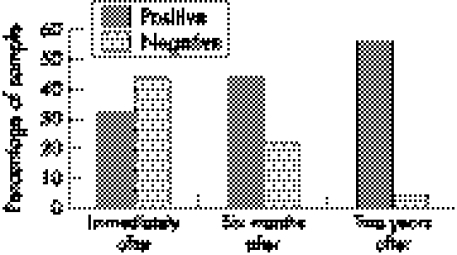

Sixty six per cent of the sample did not regret leaving the professional circuit, and, although the remaining one third regretted their decision, they did not attempt a comeback. Figure 3 shows the perceived feelings on leaving the tour up until two years after retirement. At the time of retirement, 32% had positive feelings about their decision whereas 44% had negative feelings (mainly attributed to their feelings of being “burned out”—that is, weary or fatigued—or sadness at leaving the circuit). At six months, 44% had positive feelings, 22% had negative feelings, and at two years after retirement, 56% reported positive feelings with 4% reporting negative feelings.

Figure 3 Feelings on retirement from professional tennis from the immediate onset to two years after retirement.

Pathways after retirement from competition

With regard to their knowledge of possible pathways in tennis via the NSO or state sporting organisation, 36% of the sample said that they were aware of opportunities for coaching, media, administration, or managing teams, but 64% were not.

Perceived role of the NSO

Players were asked whether there was anything the NSO could have done to change their mind about leaving the professional women's tennis circuit at the time. Sixty four per cent of players suggested that the NSO could have played a role; however, many players gave more than one direct response (table 2). On the other hand, 36% thought that there was nothing more that the NSO could have done (table 3). Other suggestions included: providing a mentor, guidance, or a sport psychologist, especially for those ranked 400–800, as they often fell outside the support given by the NSO (20%); more support given to players as they make the transition from the junior circuit, where a great amount of financial and service support is provided, to the senior circuit, where almost no support is given (8%); extra financial aid to players (4%); keeping players encouraged (4%); staff used by the NSO to be knowledgeable about those who are competing on the tour (4%); making players feel “valued” (4%).

Table 2 Responses and suggestions by participants as to whether the national sporting organisation could have helped with their transition from tennis.

| • Shown recognition before I left (9) |

| • I think that some sort of counselling or advice would have helped. I had been playing tennis for so long that I didn't realise that my life would change or that things would be different without it. I suppose I just wasn't sure what life would be like after tennis and so I think some sort of guidance would have helped so that I knew what to expect. It may have also meant that I would have continued some kind of contact with tennis rather than giving it away altogether (16) |

| • I believe that Tennis Australia should assist players in more ways by giving better information about what pathways they can take. Maybe some kind of careers advisor or a link with some colleges or universities, which will give players an opportunity and correct preparation to step into their new lifestyle a little more easily (21) |

| • It was obvious that I was leaving yet there was no encouragement or incentives to stay. That could have made a difference (26) |

| Initially – keeping players names in the game and when they are ready, keep players involved in the game so they feel able to help other players at any level. (b) Open avenues to past players – media, tournament organisation, Tennis Australia activities, offer opportunities for current and coming players to hear past players' experiences and how they did so well. (c) Communicate with past players – send letters to keep them updated with all activities they can be involved in. (d) Possible training for past players by Tennis Australia staff so that players can sign up and learn of the possible avenues within tennis. (This helps them decide and limit their possibilities of life after tennis.) (e) Provide opportunities to work with older past players whom we looked up to and share their lives and re‐training after tennis (37) |

| • They could have given some job opportunities or suggestions as to what path to take (38) |

| • [Staff member at Tennis Australia]…organised for me to see a careers counselor from the VIS which was very helpful (49) |

| • Tennis Australia could be questioning former players, and having them help present players (53) |

| • If Tennis Australia had offered to pay some expenses then I might have continued to play, but financially I could not support the travel/coaching etc without some income. In the end, I was working with Tennis Australia in my job at the AIS and was well supported in this role (45) |

| • When one loses their passion, focus, desire from what was a childhood goal, it is a huge transition to go from a sportsperson to “everyday normal living”. Things are seen in a different light. I suppose just acknowledgment …[would have been good]…and…[to]…somehow become involved in the Tennis programs would have been good, because when I retired I had a strong urge to be involved still, but was…[too]…intimidated and afraid to put up my hand as a volunteer or employee (63) |

| • Yes. (Provide)…a structure for tennis players if injuries occur or life changing experiences. Maybe phone or correspond to see if any help was needed (74) |

Subject identification in parentheses.

Table 3 Responses by players as to the role of the national sporting organisation in assisting their transition from tennis.

| • No, not really. I sought outside help to enrol in university and for career advice; maybe Tennis Australia could offer counselling and guidance with this (2) |

| • Have been in regular contact with Tennis Australia, and feel they have been helpful (4) |

| • I was OK about stopping tennis as I had my uni to fall back on and a job already organised. I was excited about my future (43) |

| • No, I don't think so. Once I made the decision to leave the tennis circuit it was a lot easier to make a clean break and distance yourself completely from Tennis Australia and all the coaching staff (56) |

| • No (29, 32, 61, 64, 67) |

| • No, I don't believe so. I didn't play for long enough to have too many hang ups. My family was my greatest support. It was just a difficult life decision I had to make as tennis had been my world for so many years (82) |

Subject identification in parentheses.

Players were asked what they thought the NSO could have done to help make the transition process easier. Half the sample (50%) did not have any expectations of assistance from the NSO, 12% thought that there could have been more recognition (or incentives given), 23% thought that the NSO could have offered some guidance, welfare, or vocational education assistance (either directly or indirectly with the provision of contact details of qualified personnel), and 15% said that the NSO had been very helpful in giving them advice about possible career prospects.

Professional assistance with process

Players were asked if they thought using a professional such as a sport psychologist to help with their transition would have helped them. Twenty nine per cent thought that it would not have assisted them, whereas 57% thought that it would have been beneficial. Seven per cent used a sport psychologist and found it to be beneficial, and 4% used one and found it not to be beneficial. One person (4%) was unsure how beneficial it would have been because “it depends on the person” (no clarifying statement was made with reference to who “the person” was). If this service was provided by the NSO, 66% of players said they would have used it, with 30% saying they would not, and one person (4%) said they may or may not have used it.

Advice to other players

All participants in the survey said that, if they were asked to counsel or advise another player considering retirement, they would tell them to think through the process properly to avoid any potential regrets later on (table 4).

Table 4 Responses by players to the question on advising other players considering retirement from tennis.

| • Understand and appreciate what a great experience and opportunity they have had in playing professional tennis and that not many jobs offer such great rewards (2) |

| • Give it everything before you go (9) |

| • I would ask them if they actually do want to leave the circuit or if they just need a break or to just take a different slant (either with coaching, fitness‐wise or psychologically) (16) |

| • You must make sure that you want to work and have a normal life. The travelling part is exciting and there was no rotation, where after tennis, it gets very predictable (23) |

| • I would probably ask them “where do you want to be in 3–5 years time?”. Do they believe they will still enjoy and will still be improving at this time? I think if they have doubts they really need to write down where they think they are and where they want to be. If all is good, keep playing. Finance is obviously a factor as well (21) |

| • Have they achieved personal success? Will they regret anything? (26) |

| • I'd really encourage them to assess if they have “given it everything”. This covers many aspects such as fitness, coaches, support network, scheduling etc. If 100% has been given, I think it would be easier to move on, not come out of retirement or be dissatisfied or frustrated about their tennis achievements. Have a break from the circuit or training before deciding to stop (27) |

| • Be sure you are happy with the effort you have given as you only have a limited time on the circuit (29) |

| • Make peace with your decision as it's hard to come back. Enjoy your last year of playing (37) |

| • Make sure you have given a lot of thought about leaving the circuit. Try not to leave too early as you might regret it years later (38) |

| • Now I would make sure a player has exhausted every possible outlet to receiving aid, support and advice (42) |

| • Make sure they feel satisfied that they have accomplished goals that they have set. Is there anything else they want to achieve before they retire? Have they maximised their ability? Has the passion gone? What is driving them (eg money, achievements)? (45) |

| • Think long and hard before leaving. This opportunity presents itself only once in your life so you need to put in 150% before you even think of throwing it all away. Don't worry too much about education and career. They will always be there but the chance to play professional tennis won't (56) |

| • Try to get as much information and feedback from coaches, players and organisations. Always have a plan for the future that you will be satisfied with (54) |

| • Do they believe that they have achieved everything they wanted to on the circuit to the best of their abilities? In other words, in 5–10 years down the track…(make sure)…they don't look back and regret leaving the circuit when they did (61) |

| • Plan ahead. Make sure they have goals for the future. Take time to really think about their decision, one way or the other. Never make that decision on the spur of the moment. Have no regrets!!!! (64) |

| • Stop for a few days, rest, relax, recover; speak to a mediator or independent person (sports counselor) who has insight rather than just significant others (coach, parents) as they are all biased; have a structured plan to overcome the issues of leaving the circuit (ie not enough support, no training partners, overtired), sport psych sessions (or whatever it is the player needs). It needs to be done via an independent person via Tennis Australia (eg through liaising with the coach and parents and significant others) (63) |

| • To be sure about their decision as it is extremely hard to make a comeback. Have plans/ideas as to what they are going to do after tennis (67) |

| • Be 100% certain. Make sure you have an idea about what you want to do and have no regrets. Move on, as life is too short! (74) |

| • Make sure you feel you have given it your best shot. You never want to die wondering what could have been (82) |

Subject identification in parentheses.

Discussion

This aim of this research was to investigate the experiences of elite Australian past players leaving the professional tennis circuit. The main findings were that most players had planned their retirement and they did not regret leaving the tour, and none of those sampled who admitted that they did not plan their retirement and/or expressed regret at leaving the tour attempted a comeback.

Previous authors24,25 have suggested that the gerontological and thanatological models for examining retirement are limited in practice because they are unable to characterise adequately the nature and dynamics of the career transition process. The findings from this study support this view and are consistent with the tenets of transition models, which focus on a process (rather than considering retirement as a single event) and mediating factors (such as the support systems for the athlete) of retirement. However, this study also highlights the idiosyncrasies of athletes retiring from professional tennis that may differ from the retirement experiences of elite athletes from other sports. This suggests that retirement should be treated as a sport specific issue using qualitative data to facilitate understanding of athletes' personal experiences of leaving elite sport.17

The sample size in this study is relatively small (28 participants). However, it should be noted that the comments made in response to the questions on reasons for and reactions to retirement are almost identical with those to similar questions posed by Allison and Meyer22 to 20 internationally ranked professional players, about 17 years earlier. The similarities between the two studies highlight the uniqueness of the professional tennis tour compared with other sports at the elite level. Although players may still leave the tour voluntarily or involuntarily, involuntary retirement may not have the same impact on tennis players as on athletes from other sports. Contributing factors may be the highly individual nature of professional tennis—comradery is not strong, with players speaking of superficial relationships and “bitchy” environments—and the fact that “selection” (by an NSO) to participate at the highest level does not exist (except in a few special circumstances such as the Fed Cup). Allison and Meyer22 reported that professional players who left the tour “…not only indicated frustration and anxiety but at the same time…saw retirement as an opportunity to reestablish a normal lifestyle…” (p 219). Similar feelings were reported by participants in this study.

The attitudinal change from negative to positive feelings seen in the sample reflects the common reactions to ending a professional sporting career. Petitpas et al26 have suggested that emotional and attitude changes may range from several months to several years, with athletes describing the time as a “rollercoaster ride”. Although not explicitly conveyed by the sample, another factor that may contribute to the positive feelings expressed by 56% of responders in this study is that 88% of the sample maintained contact with tennis (to various extents) in a variety of roles including coaching/assistant coaching, management, and/or administration. Allison and Meyer22 found that 90% of their sample felt either a “…sense of satisfaction” (50%) or “…feelings of stability/acceptance with their decision” (40%) in leaving professional tennis. These authors suggest that the high percentage of satisfaction/acceptance can be explained by most of their sample (75%) continuing to be involved with tennis in similar roles to those outlined in this study.

A secondary question investigated was whether the NSO could or should play a role in the retirement process. A number of the participants were competing on the professional tour when the Women's Tennis Department at Tennis Australia did not exist. The Women's Department was formed in 1996, with player development issues taking focus in the department in 1999, and the initiation of a specialist touring squad, for players ranked between 100 and 300, beginning in 2001. This may explain why over 60% of the sample cited little assistance from the NSO as a factor in their decision to leave (despite 50% not having any expectations of assistance) and suggesting that the NSO could have played a role in “changing their mind” about retiring. Given the current profile and role of the Women's Department in Australian tennis, further research on its role in a player's consideration of retirement is continuing.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study shows that, given the uniqueness of the professional tennis tour, a transition model of retirement, which emphasises processes and mediating factors, is well suited to tennis retirement studies. Further, the data from this study and that of Allison and Meyer22 suggest that the issue of retirement from sport should be treated as “sport specific” rather than generalising findings across the broader sporting framework. Future research should use qualitative methods with in depth interviews of athletes and develop specific methodologies and meaningful questions, such as the reasons behind “voluntary” retirement, for particular groups of athletes based on the uniqueness and idiosyncrasies of their sporting environments.17,22

As a result of these findings, which have been reported to the Board of Management of Tennis Australia, a number of initiatives have been recommended and established, particularly with the view of aiming to support lower ranked Australian players currently outside the top 300 on the tour.

What is already known on this topic

Research on career transition in tennis was limited to one study

The findings of that study suggested that retirement from the professional tennis circuit was not necessarily a traumatic experience, although some players reported initial adjustment problems

What this study adds

This study advances our knowledge of the transition process for Australian female tennis players leaving the professional international circuit

Critical issues for players when retiring and the role that a national sporting organisation (NSO) can play to assist players are identified

These include:

Setting up of a dedicated Women's Tennis web page as a central contact point for players on tour, which includes resources on the process of retirement26 and recommended autobiographical books on the topic to read

Player education19 on time and self management when playing tournaments

Recognition of player achievements, such as awarding results certificates and recognition on the Tennis Australia website

Establishing an “employment opportunities”19 section on the web page for recruiting coaches, administrators, and managers.

After the implementation of these initiatives, Tennis Australia might follow up with a study to examine the effectiveness of such initiatives in assisting players to make optimal career transitions.

Acknowledgements

This research project was commissioned and funded by Tennis Australia (the governing body of tennis in Australia).

Footnotes

Competing interests: none declared

References

- 1.Lavellee D, Anderson M B. Leaving sport: easing career transitions. In: Anderson MB, ed. Doing sport psychology. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2000249–260.

- 2.Rosenberg E. Gerontological theory and athletic retirement. In: Greendorfer SL, Yiannakis A, eds. Sociology of sport: diverse perspectives. West Point, NY: Leisure Press, 1981118–126.

- 3.Rosenberg E. Athletic retirement as social death: concepts and perspectives. In: Theberge N, Donnelly P, eds. Sport and the sociological imagination. Fort Worth: Texan Christian University Press, 1984245–258.

- 4.Parker K B. ‘Has‐beens' and ‘wanna‐bes': transition experiences of former major college football players. Sport Psychologist 19948287–304. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swain D. A Withdrawal from sport and Schlossberg's model of transitions. Sociol Sport J 19918152–160. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crook J M, Robertson S E. Transition out of elite sport. Int J Sport Psychol 22115–127. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlossberg N K. A model for analyzing human adaptation to transition. Couns Psychol 198192–18. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schlossberg N K.Counseling adults in transition: linking practice with theory. New York: Springer, 1984

- 9.Chow B C. Support for elite athletes retiring from sport: The case in Hong Kong. Journal of the International Council for Health, Physical Education, Recreation, Sport and Dance 20023836–41. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogilvie B C, Howe M. The trauma of termination from athletics. In: Williams JM, ed. Applied sport psychology. Palo Alto, CA: Mayfield, 1986365–382.

- 11.Ogilvie B C, Taylor J. Career termination issues among elite athletes. In: Singer RN, Murphy M, Tennant LK, eds. Handbook of research on sport psychology. New York: Macmillan, 1993761–775.

- 12.Werthner P, Orlick T. Retirement experiences of successful Olympic athletes. Int J Sport Psychol 198617337–363. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zaichkovsky L, Lipton G, Tucci G. Factors affecting transition from intercollegiate sport. In: Lidor R, Bar‐Eli M, eds. Innovations in sport psychology: linking theory and practice. Netanya, Israel: The Zinman Colege of Physical Education and Sport Sciences and The Wingate Institute for Physical Education and Sport, 1997782–784.

- 14.Blinde E, Greedorfer S. A reconceptualization of the process of leaving the role of competitive athlete. International Review for Sociology of Sport 19852087–93. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coakley J. Leaving competitive sport: retirement or rebirth? Quest 1983351–11. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wylleman P, De Knop P, Menkehorst H.et al Career termination and social integration among elite athletes. In: Serpa S, Alves J, Ferreira V, et al, eds. Proceedings of the 8th World Congress of Sport Psychology. Lisbon: Universidade Tecnica de Lisboa, 1993902–906.

- 17.Kerr G, Dacyshyn A. The retirement experiences of elite female gymnasts. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 200012115–133. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lavellee D, Gordon S, Grove R. Retirement from sport and loss of athletic identity. Journal of Personal and Interpersonal Loss 19972129–147. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinclair D A, Hackford D. The role of the sport organization in the career transition process. In: Lavallee D, Wylleman P, eds. Career transitions in sport: international perspectives. Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology Inc, 2000131–142.

- 20.Svoboda B, Vanek M. Retirement from high level competition. In: Orlick T, Partington J, Salmela J, eds. Mental training: for coaches and athletes. Ottawa: Coaching Association of Canada and Sport in Perspective Inc, 1982166–175.

- 21.Ungerleider S. Olympic athletes' transition from sport to workplace. Percept Mot Skills 1997841287–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allison M T, Meyer C. Career problems and retirement among elite athletes: the female tennis professional. Sociol Sport J 19985212–222. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young J A, Kane R, Pain M. Elite female past players's experiences in leaving the professional tennis circuit. Medicine and Science in Tennis 200494–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor J, Oligivie B C. A conceptual model of adaptation to retirement among athletes. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 199461–20. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy S M. Transitions in competitive sport: maximizing individual potential. In: Murphy SM, ed. Sport psychology interventions. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1995331–346.

- 26.Petitpas A, Champagne D, Chartrand J.et alAthlete's guide to career planning: keys to success from the playing field to professional life. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1997