Abstract

Objective

To describe the design, implementation, baseline data, and feasibility of establishing a disease management program for smoking cessation in rural primary care.

Method

The study is a randomized clinical trial evaluating a disease management program for smoking cessation. The intervention combined pharmacotherapy, telephone counseling, and physician feedback, and repeated intervention over two years. The program began in 2004 and was implemented in 50 primary care clinics across the State of Kansas.

Results

Of eligible patients, 73% were interested in study participation. 750 enrolled participants were predominantly Caucasian, female, employed, and averaged 47.2 years of age (SD=13.1). In addition to smoking, 427 (57%) had at least one additional major risk factor for cardiovascular disease (diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol, heart disease or stroke). Participants smoked on average 23.7 (SD=10.4) cigarettes per day, were contemplating (61%) or preparing to quit (30%), were highly motivated and confident of their ability to quit smoking, and reported seeing their physicians multiple times in the past twelve months (Median=3.50; Mean=5.48; SD=6.58).

Conclusion

Initial findings demonstrate the willingness of patients to enroll in a two-year disease management program to address nicotine dependence, even among patients not ready to make a quit attempt. These findings support the feasibility of identifying and enrolling rural smokers within the primary care setting.

Keywords: disease management, smoking cessation, tobacco use, nicotine dependence, rural health, primary care

INTRODUCTION

Although cigarette smoking is commonly considered a voluntary social act, nicotine dependence can be more accurately characterized as a chronic disease typically involving cycles of repeated quit attempts and smoking relapse (Fiore, 2000, 2008). Most models of drug dependence account for the majority of drug users experiencing challenges with abstinence and expect relapse prior to achieving long-term abstinence. However, most smoking cessation interventions offer only a single, short-term (i.e., 1–12 week) intervention and do not include a mechanism for assisting non-responders or those who relapse (Fiore, 2000; Silagy et al., 1994).

Physicians have contact with over 70% of smokers each year (Lopez-Quitero et al., 2006). Physicians who intervene, even with brief advice, can impact a patient’s smoking behavior (Pine et al, 1999; Russell et al., 1979). Unfortunately, physicians' offices often are poorly equipped to provide management of nicotine addiction in accordance with established guidelines (Rothemich et al., 2008; Orlandi, 1987; Kottke et al., 1988). Smoking cessation counseling competes with other clinical tasks and, beyond brief advice, many physicians do not routinely counsel patients who smoke (Rothemich et al., 2008; Steinberg et al., 2007; Ockene, 1987; Wells et al., 1986). Further, only a subset of smokers trying to quit receive pharmacotherapy (Steinberg et al., 2007; Ellerbeck et al., 2001; Control, 1993). However, when smoking cessation treatment is offered within primary care, the majority of patients who smoke choose to participate (Fiore et al., 2004).

Disease management programs have been created to address problems commonly encountered in chronic disease care (Eberhardt, 2001; Epstein & Sherwood, 1996). Chronic illness management and smoking cessation have been inadequately addressed in a clinical practice environment designed for acute complaints (Ellerbeck et al., 2001; Ashton, 1999; Jencks et al., 2000). Effective chronic disease management and smoking cessation programs both require systems to identify patients in need of service, track changes in health care needs over time, assure treatment in accordance with best practices, and pro-actively engage patients in behavior change (Fiore, 2000; Glasgow et al., 2001; Kottke et al., 1988). Many disease management programs utilize ‘case managers’ and proactive telephone contacts to coordinate and deliver specific elements of evidence-based care (Philbin, 1999; Rich, 1999; Rich, 2001; Wagner, 1998, 2000). Case managers function as an entity outside of the physician’s office, providing resources unavailable in the typical practice.

We developed KAN-QUIT, a disease management smoking cessation program integrated into primary care clinics in the state of Kansas. KAN-QUIT was designed to provide the support systems needed to address nicotine dependence as a chronic disease within the existing primary care system. Within this disease management program, ‘case managers’ (counselors) are part of an external intervention team able to assess and track smokers, provide behavioral counseling, and coordinate management of nicotine dependence with the primary care physician. KAN-QUIT also provides multiple opportunities for smokers to make new or repeated quit attempts.

A disease management program may be particularly suitable for primary care practices with reduced access to community-level behavioral change programs. Rural communities have higher smoking prevalence (Doescher et al., 2006) and limited cessation resources (Ellerbeck et al., 2001, 2003). Rural-dwelling adults have lower rates of health insurance coverage (Rowland & Lyons, 1989), travel longer distances for health care, and have access to fewer health care providers, particularly fewer specialists (Eberhardt, 2001). Higher rates of tobacco use, high rates of poverty, and limited access to health care strongly support the need for developing new avenues for smoking cessation in rural communities.

The goal of the KAN-QUIT study is to evaluate the effectiveness of high and low intensity disease management programs for nicotine dependence. This paper provides a preliminary report to describe the design, early implementation, and implications for adoption of disease management concepts in addressing nicotine dependence.

METHODS

All study procedures were approved and monitored by the human subjects committee of the University of Kansas Medical Center (KUMC).

Participants

Participants were recruited from fifty primary care practices within the Kansas Physicians Engaged in Practice Research (KPEPR) Network, a geographically diverse group of Kansas rural primary care clinics engaged in collaborative research with KUMC. Recruitment started in 2004, ended in 2005, and was performed by trained medical students during a rural, primary care research elective. Students universally screened all patients seen during their rotation and maintained a log of the number of patients queried and the number reporting current smoking. Patients were also accepted for screening if referred by office staff. Although we did not randomly sample from the entire population of each clinic, we believe the result is a sample broadly representing patients from rural primary care clinics. Patients were informed about the study and completed written consent. Participant information was forwarded daily to the research staff at KUMC. Trained study staff contacted participants via telephone within 6 weeks of screening to verify eligibility and conduct the baseline survey.

Eligible smokers were at least 18 years old, reported smoking at least 10 cigarettes per day for at least 25 of the past 30 days, spoke English, considered one of our participating physicians to be their regular doctor, and had a working home or cellular telephone. Individuals were excluded if pregnant or planning to become pregnant in the next two years, planning on moving in the next two years, displayed signs of dementia or other mental health disorders that would interfere with study participation, or lived with a smoker already enrolled in the study. While most smoking cessation trials enroll only individuals interested in stopping smoking, intention to quit smoking was not a criterion for participation. Instead, we utilized the ‘disease registry’ approach recommended for chronic disease management (Bonomi et al., 2002) and recruited smokers regardless of their willingness to commit to a smoking cessation attempt.

Design

The study utilized a randomized, three-arm design with intervention occurring over the course of 24 months. Participants were randomized to treatment at the individual level using simple randomization. Treatment involved four, 6-month cycles within each arm. Participants were randomized to either 1) a comparison group (C) receiving health educational mailings and an offer for free nicotine replacement therapy or bupropion every 6 months, 2) low-intensity disease management (LDM) receiving C plus a low-intensity disease management program, or 3) high-intensity disease management (HDM) receiving C plus a high intensity disease management program. At each 6-month interval, the low-intensity disease management program (LDM) included up to 2 telephone counseling sessions and a physician progress report, while the high-intensity disease management program (HDM) included up to 6 telephone-based counseling sessions plus additional progress report feedback to the physician.

Intervention

Health Education

All participants received a health education package including an incentive gift, a welcome letter, information about nicotine replacement and bupropion use for smoking cessation, and two brochures containing smoking cessation information -You Can Quit Smoking (USDHHS) and When Smokers Quit (American Cancer Society).

Pharmacotherapy

All participants were offered the choice of free bupropion or nicotine patch every six months during the study. Treatment consisted of a 6-week course of 21mg/day nicotine patch or a 7-week course of bupropion 300mg/day. Participants indicated intention to use pharmacotherapy by returning a stamped postcard included with the health educational materials or calling research staff at a toll-free number. For participants requesting the nicotine patch, research staff assessed risks and benefits and screened for contraindications via telephone. Those reporting absolute contraindications were ineligible for the patch and were offered the option of bupropion. Research staff faxed relative contraindication information to the primary care physician who either approved or disapproved patch use. Nicotine patches were mailed to eligible participants with instruction for use. If a participant requested bupropion, staff assessed risks and benefits and screened for contraindications via telephone. Participants’ current medications were reviewed by a registered pharmacist utilizing the Micromedex database to identify potential drug interactions with bupropion. Participants with absolute contraindications were denied bupropion and offered the option of the nicotine patch. Research staff faxed an assessment addressing relative contraindications and potential drug interactions along with a prescription request form to the patient’s physician. The physician made final assessment of the safety of bupropion use and, if appropriate, faxed back the signed prescription. Bupropion was mailed to eligible participants with instruction for use.

Telephone Counseling

Counseling involved a patient-centered approach based on the principles of Motivational Interviewing (MI) (Miller and Rollnick, 1991). Controlled studies have demonstrated the efficacy of MI-based counseling for alcohol (e,g,, Bien et al., 1993; Handmaker et al., 1999; Miller et al., 1993; Senft et al., 1997), heroin (Saunders et al., 1995), and nicotine addiction (Butler et al., 1999; Colby et al., 1998). Counselors completed comprehensive training and attended weekly supervision. All counseling sessions were audio-taped to assure integrity of the MI sessions.

Progress Reports to Primary Care Providers

For LDM and HDM participants, progress reports describing tobacco use, quit plan, use of pharmacotherapy, and recommendations for follow-up were faxed to their provider. A progress report was sent after the first MI counseling call (for LDM and HDM participants) and after the last MI counseling call (for HDM only) at each cycle of the study. Additional progress reports were sent every time a participant set a quit date within both HDM and LDM groups.

Measures

Baseline assessment included age, gender, race/ethnicity, annual income, education level, employment status, and marital status. Smoking history assessed number of cigarettes smoked per day, number of previous quit attempts, longest prior abstinence, previous nicotine replacement use, previous bupropion use, stage of readiness to stop smoking (Velicer et al., 1995; DiClemente et al., 1991), and the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) (Heatherton et al., 1991). Importance and confidence in quitting smoking was assessed using a 10-point Likert scale with a higher score indicating greater importance or confidence. Social and environmental variables included encouragement from friends or family to quit, smoking status of partner, number of friends that smoke, other smokers in the home, and children in the home.

Participants reported how many times they had seen their regular doctor in the past 12 months, and whether any health care provider had ever told them that they have diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol, stroke, chronic lung disease, heart disease, cancer, or depression. In addition, we identified county location of primary care practices, categorizing each country according to the 5-strata Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) population density categories (frontier, rural, densely settled rural, suburban, and urban).

The primary outcome measure will be 7-day point prevalence smoking abstinence at month 24 (i.e. ‘having smoked no cigarettes, not even a puff in the past 7 days’) to assess accumulative effects of the four 6-month intervals of the disease management intervention. Secondary outcomes will include self-reported point prevalence abstinence at 6, 12, and 18 months; continuous abstinence at 12, 18, and 24 months; biochemically confirmed abstinence at 12 and 24 months; frequency of quit attempts and progression in stage of readiness to stop smoking at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months. We will measure and evaluate potential mediating factors including uptake of pharmacotherapy, counseling calls completed, and discussions with physicians during each 6-month interval of the program. Finally, we intend to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the treatment arms. Intensity of an intervention may be highly correlated with cost, yet more intensive interventions may actually be more cost-effective (Fiore, 2000).

RESULTS

Of 50 rural primary care practices participating in this study, most (78%) of the practices were located in counties designated as frontier, rural or densely settled rural. The remaining practices were located in remote parts of counties designated as urban or semi-urban. Of these, 7 were in remote geographic regions within those counties and 4 were in larger towns (population 15,000–50,000) geographically separated from the five metropolitan municipalities within the state. More than half (57%) of the counties represented have median income below $35,000, and 56% of the counties have more than 11% of the population living below the poverty line.

Out of 80 physicians participating in our study 75% responded to a brief survey about their practice. The majority of physicians were male (68.3%), practicing in family medicine (90%), and highly interested in participating in future research programs (97%).

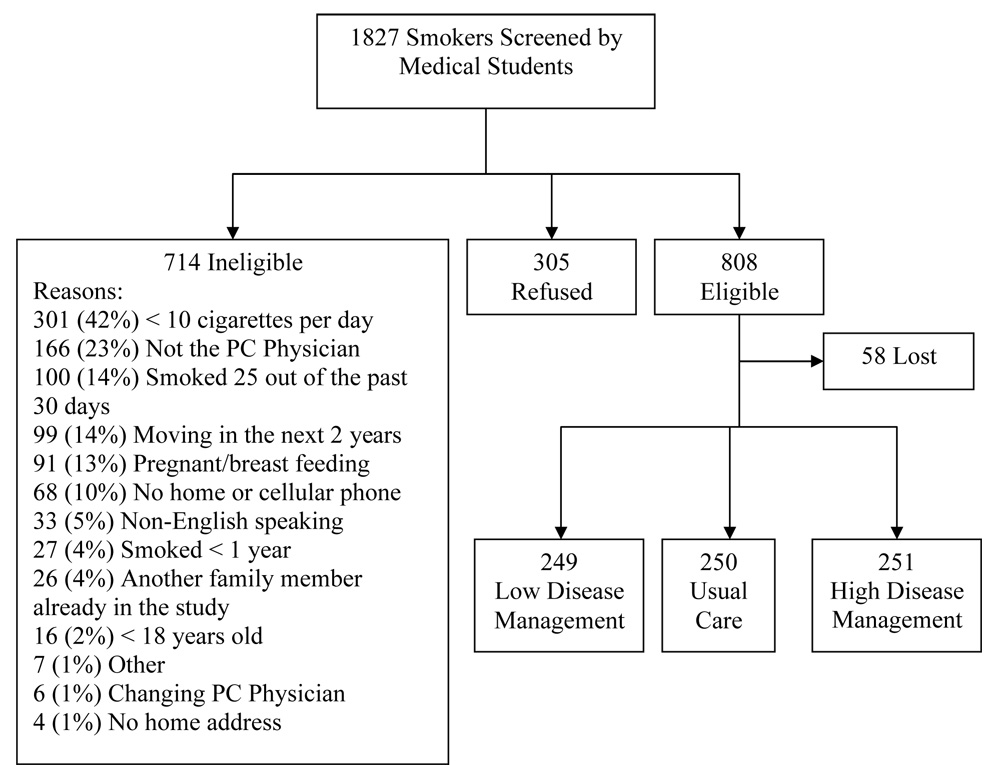

Study recruitment and enrollment data are presented in Figure 1. Of 1827 identified smokers, 305 (16.7%) declined participation, 714 (39.1%) were ineligible, and 808 (44.2%) were eligible for the study. Of 714 ineligible smokers, 401 were ineligible due to light patterns of smoking characterized by smoking fewer than 10 cigarettes per day (42%) or smoking less than daily (14%). Of 808 eligible smokers, 58 (7.2%) were lost to follow-up prior to baseline assessment and randomization, and 750 were randomized to the three treatment conditions.

Figure 1.

Screening and enrollment of study participants, Kansas, United States (2004–2005).

Table 1 presents baseline demographic characteristics of the 750 study participants. Participants were largely Caucasian (>90%), female, employed, and averaged 47.2 years of age (SD=13.1). Almost half the sample had some post-high school education. Similar to national data (Hedley et al., 2004), BMI calculations indicated two thirds of the sample were either overweight (31.2%) or obese (35.5%). Roughly one third of the participants reported being previously diagnosed with depression, high cholesterol, hypertension, or chronic lung disease. In addition to their active smoking status, 427 (57%) had at least one additional major risk factor for cardiovascular disease (diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol, heart disease or stroke).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics and self-reported medical history of rural smokers in Kansas, United States (2004–2005)

| Total | ||

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | ||

| Age | ||

| <=50 years | 440 (58.7) | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 439 (58.5) | |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married/Partner | 504 (67.2) | |

| Divorced | 136 (18.1) | |

| Widowed | 43 (5.7) | |

| Separated | 18 (2.4) | |

| Never Married | 49 (6.5) | |

| Employment Status | ||

| Full time | 437 (58.3) | |

| Part Time | 66 (8.8) | |

| Not Employed | 247 (32.9) | |

| Education | ||

| ≤High School | 385 (51.3) | |

| Diabetes | 101 (13.5) | |

| Hypertension | 258 (34.4) | |

| High Cholesterol | 269 (35.9) | |

| Stroke | 34 (4.5) | |

| Chronic Lung Disease | 202 (26.9) | |

| Heart Disease | 73 (9.7) | |

| Cancer | 37 (4.9) | |

| Depression | 304 (40.5) | |

| Weight, mean (SD) lbs | 182.8 (50.6) | |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) kg/m2 | ||

| < 25 | 248 (33.1) | |

| 25–29 | 235 (31.4) | |

| ≥30 | 266 (35.5) | |

Smoking characteristics are presented in Table 2. Participants on average smoked 23.7 (SD=10.4) cigarettes per day and less than one third reported using menthol cigarettes (21.9%). Many participants had previously used either nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) (52.9%, N=397) or bupropion (32.7%, N=245) to stop smoking. Overall, participants were contemplating quitting, and were highly motivated and confident of their ability to quit smoking. In addition, almost half of the participants reported having a spouse/partner currently smoking (41.2%), having one or more other smokers in the household (46.0%), and having no smoking restrictions in the home (45.5%). Participants reported seeing their physicians multiple times in the past twelve months (Median=3.50; Mean=5.48; SD=6.58).

Table 2.

Smoking history characteristics of rural smokers in Kansas, United States (2004–2005)

| Current Smoking | |

| Current Cigarettes Per Day, mean (SD) | 23.7 (10.4) |

| Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND), mean (SD) | 5.2 (2.2) |

| Smoke mentholated cigarettes | 164 (22%) |

| Brand of cigarettes, n (%) | |

| Marlboro | 277 (37%) |

| Doral | 50 (7%) |

| Camel | 45 (6%) |

| GPC | 37 (5%) |

| Other1 | 341 (45%) |

| Smoking History | |

| Age started smoking regularly, mean (SD), yr | 17.9 (6.5) |

| Number of quit attempts in past 6 months, mean (SD) | 0.72 (1.5) |

| Prior use of pharmacotherapy, n (%) | |

| Nicotine replacement therapy | 397 (53%) |

| Bupropion (Zyban) | 245 (33%) |

| Longest period of past abstinence, n (%) | |

| < 24 hours | 41 (5%) |

| 1–7 days | 147 (20%) |

| 8–30 days | 112 (15%) |

| 1–6 months | 161 (21%) |

| ≥ 6 months | 252 (34%) |

| Never tried quitting | 37 (5%) |

| Psychometric Measures | |

| Readiness to Stop Smoking, n (%) | |

| Precontemplation | 65 (9%) |

| Contemplation | 457 (61%) |

| Preparation | 228 (30%) |

| Confidence in quitting, mean (SD) | 6.1 (2.7) |

| Importance of quitting, mean (SD) | 8.6 (2.1) |

Any other reported brand, each reported by less than 5% of participants

DISCUSSION

The current paper described the design, recruitment, and baseline data for the first evaluation of a disease management program for nicotine dependence. Initial findings from the KAN-QUIT study demonstrate the feasibility of identifying and enrolling rural smokers within the primary care setting. Enrollment shows smokers in primary care settings are willing to participate in a two-year disease management program to address nicotine dependence.

Initial findings from KAN-QUIT participants support the rationale for a disease management approach to treating nicotine dependence. Indeed, 95% of KAN-QUIT participants reported making previous quit attempts, and one third of the sample reported having maintained abstinence for 6 months or more in the past. Although these individuals experienced subsequent relapse, they acknowledged the importance of quitting and were willing to re-engage in treatment. Moreover, these smokers made a commitment to participate in smoking cessation intervention over the course of two years. Such commitment is important given that smokers at all stages of readiness to change were approached for inclusion in the KAN-QUIT program. While the vast majority of treatment interventions have targeted only smokers preparing to stop smoking (Fiore, 2000), the disease management approach is applied to all smokers. Notably, two thirds of the smokers in this sample were not preparing to stop smoking at baseline yet agreed to participate in the two-year KAN-QUIT intervention.

The participants reported high frequency of contact with their primary care provider, highlighting the potential for utilizing the doctor-patient contact to facilitate smoking cessation. Previous data demonstrate the challenges of effectively addressing tobacco use within primary care and emphasize the need for programs to assist the healthcare provider (Ellerbeck et al., 2003). A disease management approach may address this gap. Initial implementation of the KAN-QUIT protocol supports the feasibility of incorporating a disease management program for nicotine dependence, combining telephone counseling and physician feedback, into the primary care setting. While intensive intervention from nicotine dependence specialists is not possible within most primary care settings, identification of smokers and referral to a disease management program is feasible. Telephone counseling further increases access to treatment for smokers. Data from KAN-QUIT supports the feasibility of telephone counseling in the rural setting, as 96% of screened patients reported having a working telephone. The access to external nicotine dependence specialists allows primary care physicians to address nicotine dependence and arrange follow-up within the limited scope of the office visit. The combined telephone counseling and individualized physician feedback is expected to produce client-centered smoking cessation intervention. Compared to standard interventions, tailored interventions may enhance smoking cessation self-efficacy and increase abstinence outcomes (Dijkstra et al., 1999; Shiffman et al., 2000; Shiffman et al., 2001).

The KAN-QUIT intervention provides multiple opportunities to use pharmacotherapy and telephone counseling to aid cessation and abstinence maintenance. Repeated intervention and extended treatment are expected to improve abstinence rates (Shiffman et al., 2004; Durcan et al., 2002; Gonzales et al., 2001; Hays et al., 2001; Hall et al., 2004). Data show that many smokers who relapse following biobehavioral intervention will successfully achieve abstinence with subsequent pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation (Shiffman et al., 2004; Durcan et al., 2002; Gonzales et al., 2001). Due to the chronic nature of tobacco use, extended treatment and repeated intervention may be required to aid quit attempts, increase periods of abstinence, and decrease relapse, thereby improving long-term smoking abstinence (Tonnesen et al., 1996).

Current findings show a notable rate of co-morbidity within this sample of rural smokers. Rates of depression, hypertension, chronic lung disease, diabetes, and obesity suggest the potential need for addressing multiple health issues and health behaviors within an effective intervention. Fifty-seven percent of our participants reported at least one major risk factor for cardiovascular disease in addition to their active smoking, making this a particularly important population requiring intervention to facilitate stopping smoking. Many smoking cessation clinical trials exclude individuals with comorbidity. Because individuals with comorbidity are not excluded from the KAN-QUIT program, this study will be able to examine use of pharmacotherapy within a broad patient base. Furthermore, high rates of comorbidity in our sample emphasize the importance of integrating the primary care provider as a central figure within the smoking cessation intervention to address individual needs related to co-existent diseases and assess potential contraindications to pharmacotherapy use.

The high prevalence (40%) of lifetime depression among smokers in the current study is consistent with previous investigations (Glassman et al., 1990; Hall et al., 1996; Kinnunen et al., 1996). Depressed smokers are less likely to quit smoking (Breslau et al., 1992; Lasser et al., 2000) and those who quit tend to relapse earlier than non-depressed smokers (Glassman et al., 1990; Kinnunen et al., 1996). Smokers with a history of depression are more likely to experience a depressive episode when trying to quit (Covey et al., 1998), and experience more severe withdrawal symptoms (Breslau et al., 1992; Breslau et al., 1993). Due to the paucity of mental health resources within rural communities, a disease management model may be well suited to address key comorbid factors.

One strength of this study is the ability to report elements of external validity, as recommended within the RE-AIM framework (Dzewaltowski et al., 2004). The RE-AIM framework [reach, efficacy/effectiveness, adoption, implementation and maintenance] can be used to evaluate dimensions central to translating research to practice for health promotion interventions, including chronic disease management (Dzewaltowski et al., 2004; Glasgow et al., 2001). Our high level of participation (more than 70% of eligible smokers agreed to study participation) produced a broad sample of rural primary care patients and supports the wide reach of this intervention. Indeed, the high level of participation in KAN-QUIT is notable. In contrast, rates of participation from the general target population are typically unknown (Dzewaltowski et al., 2004). Moreover, KAN-QUIT participants include smokers at all stages of readiness to stop smoking, and include individuals with diverse medical comorbidity. Furthermore, the KAN-QUIT study design will allow evaluation of maintenance of behavior change over the course of two years, providing a unique examination of participant engagement and adherence, relapse and repeated quit attempts, choice and use of pharmacotherapy over time.

Enrollment data from this study points to the need of intervention for light smokers. Of the 1827 patients screened, one in five reported patterns of smoking characterized by smoking fewer than 10 cigarettes per day or smoking less than daily. Although light smokers desire professional help to quit, they are less likely to receive physician advice to stop smoking (Owen et al., 1995) and are typically excluded from clinical trials. However, the USDHHS Clinical Practice Guidelines specifically recommend biobehavioral intervention for all smokers (Fiore, 2000). Therefore, this group must not be overlooked by healthcare providers and should be considered in future research.

CONCLUSIONS

The KAN-QUIT study implements a disease management approach to treating the chronic condition of tobacco use and nicotine dependence. The program incorporates pharmacotherapy, telephone counseling, and physician feedback with repeated intervention over two years. Initial findings support the feasibility of identifying and enrolling rural smokers within the rural primary care setting. Findings show smokers across stages of readiness to stop smoking are willing to enroll in a two-year disease management program to address nicotine dependence.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by grant number CA 1102390 from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to thank Carla Berg, Genevieve Casey, Olivia Chang, Andrea Elyacher, Tresza Hutcheson, Shawn Jeffries, Terri Tapp and the KAN-QUIT associates for their efforts on this project. We are also grateful to the volunteers who participated in this research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

PRECIS

Initial KAN-QUIT findings support the feasibility of initiating a disease management program for tobacco use treatment within a primary care setting and enrolling 750 rural smokers for long-term intervention.

REFERENCES

- Ashton CM. Care of patients with failing hearts: evidence for failures in clinical practice and health services research. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:138–140. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bien TH, Miller WR, Boroughs JM. Motivational interviewing with alcohol outpatients. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1993 [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi AE, Wagner EH, Glasgow RE, Vonkorff M. Assessment of chronic illness care (ACIC): a practical tool to measure quality improvement. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:791–820. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Kilbey MM, Andreski P. Nicotine withdrawal symptoms and psychiatric disorders: findings from an epidemiologic study of young adults. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:464–469. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.4.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Kilbey MM, Andreski P. Nicotine dependence and major depression. New evidence from a prospective investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:31–35. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820130033006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler CC, Rollnick S, Cohen D, Russell I, Bachmann M, Stott N. Motivational consulting versus brief advice for smokers in general practice: A randomized trial. British Journal of General Practice. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- Colby SM, Monti PM, Barnett NP, Rohsenow DJ, Weissman K, Spirito A, Woolard RH, Lewander WJ. Brief motivational interviewing in a hospital setting for adolescent smoking: a preliminary study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:574–578. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Control CFD. Physician and other health-care professional counseling of smokers to quit--United States, 1991. MMWR. 1993;42:854–857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covey LS, Glassman AH, Stetner F. Cigarette smoking and major depression. J Addict Dis. 1998;17:35–46. doi: 10.1300/J069v17n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO, Fairhurst SK, Velicer WF, Velasquez MM, Rossi JS. The process of smoking cessation: an analysis of precontemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:295–304. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra M, Mesters I, DeVries H, Van Breukelen G, Parcel GS. Effectiveness of a social influence approach and boosters to smoking prevention. Health Educ Res. 1999;14:791–802. doi: 10.1093/her/14.6.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doescher MP, Jackson JE, Jerant A, Gary Hart L. Prevalence and trends in smoking: a national rural study. J Rural Health. 2006;22:112–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2006.00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durcan MJ, White J, Jorenby DE, Fiore MC, Rennard SI, Leischow SJ, Nides MA, Ascher JA, Johnston JA. Impact of prior nicotine replacement therapy on smoking cessation efficacy. Am J Health Behav. 2002;26:213–220. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.26.3.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzewaltowski DA, Estabrooks PA, Klesges LM, Bull S, Glasgow RE. Behavior change intervention research in community settings: how generalizable are the results? Health Promot Int. 2004;19:235–245. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dah211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzewaltowski DA, Glasgow RE, Klesges LM, Estabrooks PA, Brock E. RE-AIM: evidence-based standards and a Web resource to improve translation of research into practice. Ann Behav Med. 2004;28:75–80. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2802_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhardt MSID, Makuc DM, et al. Health United States, 2001. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics; 2001. Urban and Rural Health Chartbook. [Google Scholar]

- Ellerbeck EF, Ahluwalia JS, Jolicoeur DG, Gladden J, Mosier MC. Direct observation of smoking cessation activities in primary care practice. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:688–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellerbeck EF, Choi WS, McCarter K, Jolicoeur DG, Greiner A, Ahluwalia JS. Impact of patient characteristics on physician's smoking cessation strategies. Prev Med. 2003;36:464–470. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(02)00055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein RS, Sherwood LM. From outcomes research to disease management: a guide for the perplexed. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:832–837. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-9-199605010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: A US Public Health Service report. The Tobacco Use and Dependence Clinical Practice Guideline Panel, Staff, and Consortium Representatives. Jama. 2000;283:3244–3254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ. Treating tobacco use and dependence: Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: United States Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, McCarthy DE, Jackson TC, Zehner ME, Jorenby DE, Mielke M, Smith SS, Guiliani TA, Baker TB. Integrating smoking cessation treatment into primary care: an effectiveness study. Prev Med. 2004;38:412–420. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, McKay HG, Piette JD, Reynolds KD. The RE-AIM framework for evaluating interventions: what can it tell us about approaches to chronic illness management? Patient Educ Couns. 2001;44:119–127. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00186-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Orleans CT, Wagner EH. Does the chronic care model serve also as a template for improving prevention? Milbank Q. 2001;79:579–612. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00222. iv–v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassman AH, Helzer JE, Covey LS, Cottler LB, Stetner F, Tipp JE, Johnson J. Smoking, smoking cessation, and major depression. Jama. 1990;264:1546–1549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales DH, Nides MA, Ferry LH, Kustra RP, Jamerson BD, Segall N, Herrero LA, Krishen A, Sweeney A, Buaron K, Metz A. Bupropion SR as an aid to smoking cessation in smokers treated previously with bupropion: a randomized placebo-controlled study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;69:438–444. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2001.115750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SM, Humfleet GL, Reus VI, Munoz RF, Cullen J. Extended nortriptyline and psychological treatment for cigarette smoking. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2100–2107. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SM, Munoz RF, Reus VI, Sees KL, Duncan C, Humfleet GL, Hartz DT. Mood management and nicotine gum in smoking treatment: a therapeutic contact and placebo-controlled study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:1003–1009. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handmaker NS, Miller WR, Manicke M. Findings of a pilot study of motivational interviewing with pregnant drinkers. J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60:285–287. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays JT, Hurt RD, Rigotti NA, Niaura R, Gonzales D, Durcan MJ, Sachs DP, Wolter TD, Buist AS, Johnston JA, White JD. Sustained-release bupropion for pharmacologic relapse prevention after smoking cessation. a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2001 doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-6-200109180-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedley AA, Ogden CL, Johnson CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999–2002. Jama. 2004;291:2847–2850. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.23.2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jencks SF, Cuerdon T, Burwen DR, Fleming B, Houck PM, Kussmaul AE, Nilasena DS, Ordin DL, Arday DR. Placebo controlled trial of nicotine chewing gum in general practice. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 2000;289:794–797. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6448.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnunen T, Doherty K, Militello FS, Garvey AJ. Depression and smoking cessation: characteristics of depressed smokers and effects of nicotine replacement. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:791–798. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.4.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kottke TE, Battista RN, Defriese GH, Brekke ML. Attributes of successful smoking cessation interventions in medical practice. A meta-analysis of 39 controlled trials. Jama. 1988;259:2883–2889. doi: 10.1001/jama.259.19.2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: A population-based prevalence study. Jama. 2000;284:2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Quitero C, Crum RM, Neumark YD. Racial-ethnic disparities in report of physician-provided smoking cessation advine: analysis of the 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(8):2235–2239. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.071035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Benefield RG, Tonigan JS. Enhancing motivation for change in problem drinking: a controlled comparison of two therapist styles. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:455–461. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ockene JK. Physician-delivered interventions for smoking cessation: strategies for increasing effectiveness. Prev Med. 1987;16:723–737. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(87)90054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ockene JK. Smoking intervention: the expanding role of the physician. Am J Public Health. 1987;77:782–783. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.7.782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlandi MA. Promoting health and preventing disease in health care settings: an analysis of barriers. Prev Med. 1987;16:119–130. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(87)90011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen N, Kent P, Wakefield M, Roberts L. Low-rate smokers. Prev Med. 1995;24:80–84. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philbin EF. Comprehensive multidisciplinary programs for the management of patients with congestive heart failure. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:130–135. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine D, Sullivan S, Conn SA, David C. Promoting tobacco cessation in primary care practice. Prim Care. 1999;26(3):591–610. doi: 10.1016/s0095-4543(05)70119-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich MW. Heart failure disease management: a critical review. J Card Fail. 1999;5:64–75. doi: 10.1016/s1071-9164(99)90026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich MW. Heart failure disease management programs: efficacy and limitations. Am J Med. 2001;110:410–412. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00632-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothemich SF, Woolf SH, Johnson RE, Burgett AE, Flores SK, Marsland DW, Ahluwalia JS. Effect on cessation counseling of documenting smoking status as a routine vital sign: An ACORN study. An Fam Med. 2008;6(1):60–68. doi: 10.1370/afm.750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland D, Lyons B. Triple jeopardy: rural, poor, and uninsured. Health Serv Res. 1989;23:975–1004. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell MA, Wilson C, Taylor C, Baker CD. Effect of general practitioners' advice against smoking. Br Med J. 1979;2:231–235. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6184.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders B, Wilkinson C, Phillips M. The impact of a brief motivational intervention with opiate users attending a methadone programme. Addiction. 1995 doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.90341510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senft RA, Polen MR, Freeborn DK, Hollis JF. Brief intervention in a primary care setting for hazardous drinkers. Am J Prev Med. 1997;13:464–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Dresler CM, Rohay JM. Successful treatment with a nicotine lozenge of smokers with prior failure in pharmacological therapy. Addiction. 2004;99:83–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Paty JA, Rohay JM, Di Marino ME, Gitchell J. The efficacy of computer-tailored smoking cessation material as a supplement to nicotine polacrilex gum therapy. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1675–1681. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.11.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Paty JA, Rohay JM, Di Marino ME, Gitchell JG. The efficacy of computer-tailored smoking cessation material as a supplement to nicotine patch therapy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;64:35–46. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00237-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silagy C, Mant D, Fowler G, Lodge M. Meta-analysis on efficacy of nicotine replacement therapies in smoking cessation. Lancet. 1994;343:139–142. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90933-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg MB, Nanavati K, Delnevo CD, Abatemarco DJ. Predictors of self-reported discussion of cessation medications by physicians in New Jersey. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:3045–3053. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonnesen P, Mikkelsen K, Norregaard J, Jorgensen S. Recycling of hard-core smokers with nicotine nasal spray. Eur Respir J. 1996;9:1619–1623. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09081619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velicer WF, Fava JL, Prochaska JO, Abrams DB, Emmons KM, Pierce JP. Distribution of smokers by stage in three representative samples. Prev Med. 1995;24:401–411. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract. 1998;1:2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EH. The role of patient care teams in chronic disease management. Bmj. 2000;320:569–572. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells KB, Lewis CE, Leake B, Schleiter MK, Brook RH. The practices of general and subspecialty internists in counseling about smoking and exercise. Am J Public Health. 1986;76:1009–1013. doi: 10.2105/ajph.76.8.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.