Abstract

Our research goal is to discover the principles underlying natural communication among individuals and to establish a methodology for the development of expressive humanoid robots. For this purpose we have developed androids that closely resemble human beings. The androids enable us to investigate a number of phenomena related to human interaction that could not otherwise be investigated with mechanical-looking robots. This is because more human-like devices are in a better position to elicit the kinds of responses that people direct toward each other. Moreover, we cannot ignore the role of appearance in giving us a subjective impression of human presence or intelligence. However, this impression is influenced by behavior and the complex relationship between appearance and behavior. This paper proposes a hypothesis about how appearance and behavior are related, and maps out a plan for android research to investigate this hypothesis. We then examine a study that evaluates the human likeness of androids according to the gaze behavior they elicit. Studies such as these, which integrate the development of androids with the investigation of human behavior, constitute a new research area that fuses engineering and science.

Keywords: Android, human–robot communication, human likeness, appearance and behavior, gaze behavior

1. INTRODUCTION

Our everyday impressions of intelligence are subjective phenomena that arise from our interactions with others. The development of systems that support rich, multimodal interactions will be of enormous value. Our research goal is to discover the principles underlying natural communication among individuals and to establish a methodology for the development of expressive humanoid robots. The top-down design of robots that support natural communication is impossible because human models do not fulfill the necessary requirements. We adopt a constructivist approach that entails repeatedly developing and integrating behavioral models, implementing them in humanoid robots, analyzing their flaws, and then improving and reimplementing them [1].

By following this constructivist approach in a bottom-up fashion, we have developed a humanoid robot, ‘Robovie,’ which has numerous situation-dependent behavior modules and episode rules to govern the various combinations of these modules and rules [2]. This has enabled us to study how Robovie's behavior influences human–robot communication [3]. However, based on the fact that human beings have evolved specialized neural centers for the detection of bodys and faces (e.g., Ref. [4]), we can infer that a human-like appearance is also important. Apart from gestures, human beings may also possess many biomechanical structures that support interaction, including scores of muscles for controlling facial expressions and the vocal tract. Robovie's machine-like appearance will have an impact on interaction, thereby preventing us from isolating the effects of behavior. Other studies have also tended to focus only on behavior and have entrusted the robot's appearance to an artistic designer. However, in order to isolate the effects of behavior from those of appearance, it is necessary to develop an android robot that physically resembles a person. Our study addresses the appearance and behavior problem from the standpoint of both engineering and science. We also explore the essence of communication through the development of androids.

Studies on androids have two research aspects:

The development of a human-like robot based on mechanical and electrical engineering, robotics, control theory, pattern recognition and artificial intelligence.

An analysis of human activity based on the cognitive and social sciences.

These aspects interact closely with each other: in order to make the android human-like, we must investigate human activity from the standpoint of the cognitive and behavioral sciences as well as the neurosciences, and in order to evaluate human activity, we need to implement processes that support it in the android.

Research on the development of communication robots has benefited from insights drawn from the social and life sciences. However, the contribution of robotics to these fields has thus far been insufficient, partly because conventional humanoid robots appear mechanical and, therefore, have an impaired ability to elicit interpersonal responses. To provide an adequate testbed for evaluating models of human interaction, we require robots that allow us to consider the effects of behavior separately from those of appearance.

Conversely, research in the social and life sciences generally takes a human-like appearance for granted or overlooks the issue of appearance altogether. Thus, the applicability of such research is unclear. However, these problems can be potentially overcome through the judicious use of androids in experiments with human subjects. The application of androids to the study of human behavior can be viewed as a new research area that fuses engineering and science, in contrast to existing approaches in humanoid robotics that fail to control for appearance. This paper proposes a direction for android research based on our hypothesis on the relationship between appearance and behavior. It also reports a study that evaluates the human likeness of an android based on human gaze behavior.

Gaze behavior in human–human interaction has been studied in psychology and cognitive science. For example, some psychological researchers studied functions of eye contact in human–human conversation [5], and a relationship between duration of eye contact and interpersonal relationship [6]. According to existing studies on human gaze behavior, we can infer that the gaze behavior is influenced by interpersonal relationship. Conversely, we can infer that the interpersonal relationship can be evaluated by observing the person's gaze behaviors. In this paper, gaze behaviors in human–android interaction are compared with those in huamn–human interaction in order to evaluate human likeness of an android.

2. A RESEARCH MAP BASED ON THE APPEARANCE AND BEHAVIOR HYPOTHESIS

2.1. A hypothesis about a robot's appearance and behavior

It may appear that the final goal of android development should be to realize a device whose appearance and behavior cannot be distinguished from those of a human being. However, since there will always be subcognitive tests that can be used to detect subtle differences between the internal architecture of a human being and that of an android [7, 8], an alternative goal could be to realize a device that is almost indistinguishable from human beings in everyday situations. In the process of pursuing this goal, our research also aims to investigate the principles underlying interpersonal communication.

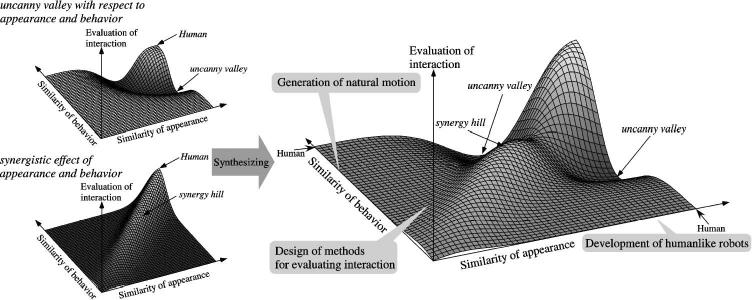

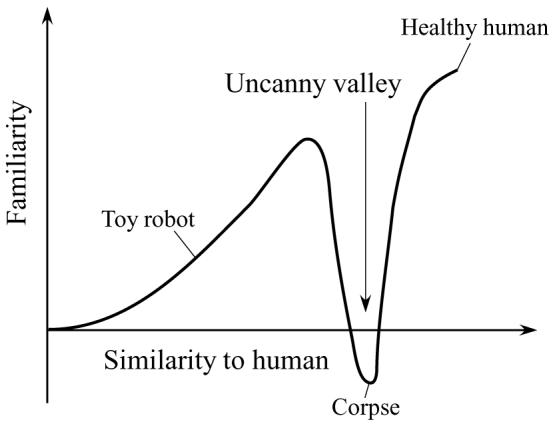

A significant problem for android development is the ‘uncanny valley,’ which was first suggested by Mori [9, 10]. He discussed the relationship between a robot's similarity to a human and a subject's perception of familiarity. A robot's familiarity increases with its similarity until a certain point is reached at which imperfections cause the robot to appear repulsive (Fig. 1). This sudden drop is termed the uncanny valley. A robot in the uncanny valley may seem like a corpse. We are concerned that these robots we create in our development of androids could also fall into the uncanny valley due to imperfections in appearance. Therefore, it is necessary to adopt a methodology that will enable us to overcome the uncanny valley.

Figure 1.

In Fig. 1, the effect of similarity can be decomposed into the effects of appearance and behavior because both factors interdependently influence human–robot interaction. We hypothesize that the relationship between appearance and behavior can be characterized by the graph in Fig. 2, which superimposes graphs derived from the uncanny valley hypothesis with respect to appearance and behavior, as well as the hypothesis that there is a synergistic effect on interaction when appearance and behavior are well matched [11]. Simply put, we hypothesize that an android's un-canniness can be mitigated by its behavior, if the behavior closely resembles that of a person.

Figure 2.

The extended uncanny valley and a map for its investigation.

2.2. The android research map

The axes in Fig. 2 are not clearly defined. How do we quantify similarity and how do we evaluate human–robot interaction? In order to answer these questions, three main research issues need to be addressed.

2.2.1. A method to evaluate human–robot interaction

Human–robot interaction can be evaluated by its degree of ‘naturalness.’ Therefore, it is necessary to compare human–human and human–robot interactions. There are qualitative approaches to measure a mental state using methods such as the semantic differential method. There also exist quantitative methods to observe an individual's largely unconscious behavior, such as gaze behavior, interpersonal distance and vocal pitch. These observable responses reflect cognitive processes that we might not be able to infer from responses to a questionnaire. In this research, we study how a human subject's responses reflect the human-like quality of an interaction and how these responses are related to the subject's mental state.

2.2.2. Implementing natural motion in androids

In order to elucidate the types of motion that make people perceive an android's behavior as being natural, we attempt to mimic an individual's motion precisely and then monitor how a human subject's interaction with the android degrades as we remove some aspect of the android's motion. A straightforward method by which to animate the android is through the implementation of the motion of an actual human subject, as measured by a motion capture system. Most methods that use a motion capture system assume that a human body has the same kinematic structure as a robot and calculate the joint angles using the robot's kinematics (e.g., Ref. [12]). However, since the kinematic structure of humans and robots differ, there is no guarantee that the robot's motion, as generated from the angles, will resemble human motion. Therefore, we require a method that will ensure that the motions we view at the surface of the robot resemble those of a human being [13].

2.2.3. The development of human-like robots

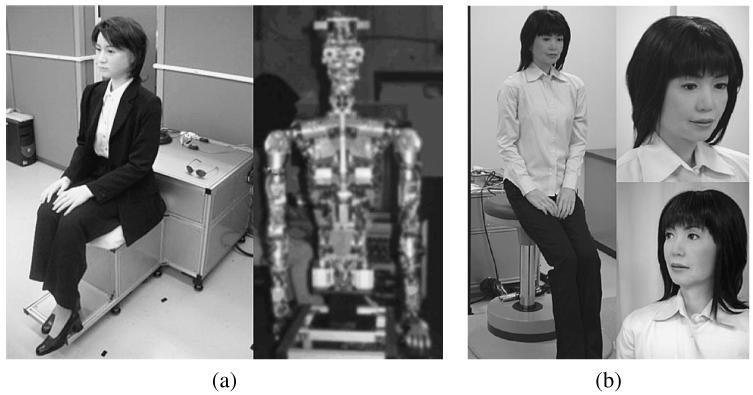

We have developed two androids that are currently being used for experimentation. Repliee R1, shown in Fig. 3, is based on an actual 5-year-old girl. We took a cast of her body to mold the android's skin, which is composed of a type of silicone that has a human-like feel. The silicone skin covers the entire body of the android. To enable it to assume various postures, it has 9 d.o.f. in the head (two for the eyelids, three for the eyes, one for the mouth and three for the neck) and many free joints. All actuators (electrical motors) are embedded within the body. The main limitations of this android are as follows:

Repliee R1's range of motion is limited by the low elasticity of the silicone skin.

The facial expression cannot be changed.

The eye and eyelid mechanisms are not perfectly realized, which is a drawback because people are usually sensitive to imperfections in the eyes.

These limitations must be overcome in order to achieve a human-like appearance.

Figure 3.

The developed android Repliee R1.

Repliee Q1, shown in Fig. 4a, is our other android; this android was developed to realize human-like motion. It has 31 d.o.f. in the upper body. It can generate various kinds of micro-motions such as the shoulder movements that are typically caused by human breathing. Silicone skin covers only its head, neck, hands and forearms, thereby enabling a wide range of motions to be realized. The compliance of the air actuators makes for safer interactions. Highly sensitive tactile sensors mounted just under the android's skin enable contact interaction.

Figure 4.

The developed androids Repliee Q1 (a) and Repliee Q2 (b). The details of the internal mechanism are blurred.

Repliee Q1 has now been upgraded to Repliee Q2 shown in Fig. 4b. It has 42 d.o.f., and can make facial expressions and finger motions in addition to the movements that Repliee Q1 can make. It has 16 d.o.f. in the head (one for the eyebrows, one for the eyelids, three for the eyes, seven for the mouth, one for the cheeks and three for the neck). The face was modeled after a particular Japanese woman in order to realize a more human-like appearance. The facial expressions of the android enable various social interactions.

We are studying the appearance and behavior problem while integrating these research issues. In the next section, we present a study to evaluate the human likeness of the android based on human gaze behavior during communication.

3. EVALUATION OF THE HUMAN LIKENESS OF THE ANDROID

In order to make the android human-like, we must evaluate the human likness of the android. Therefore, as mentioned above, it is necessary to compare human–human and human–android interactions. Apart from the android, Oztop et al. [14] adopted an experimental paradigm of motor interference to investigate how similar the implicit perception of a humanoid robot is to a human agent. They measured the amount of interference in a subject's movement when s/he performed an action which was incongruent to other's action and evaluated the human likeness of the humanoid robot with the interference effect. In the evaluation of a human–robot interaction, methods of evaluating a human subject's (largely unconscious) responses provide a complementary source of information to the insights gleaned from a questionnaire or focus group. Therefore, the difference between human–human and human–android interactions can be evaluated by observing such person's responses as can be influenced by a social relationship to other individuals.

In our previous work, we studied the interaction between the android Repliee R1 and a person [15]. We focused on the subject's gaze fixation during a conversation. The pattern of fixation in the case of the android interlocutor was different from that of a human interlocutor. Many subjects perceived the android's appearance and movement to be artificial. Thus, we concluded that the unnaturalness of the android affected the subjects' gaze fixation.

This paper evaluates the human likeness of the android Repliee Q1, which has an improved appearance and better movement. The evaluation method in the previous work was not considered appropriate for use because the task of the subject was not well controlled. In this study, we focus on a particular aspect of gaze behavior, which is evaluated through a set of experiments. On the one hand, this helps to investigate the design methodology of humanoid robots; on the other hand, by studying the nature of gaze behavior, we can contribute to cognitive science and psychology.

3.1. Breaking eye contact while thinking

Gaze behaviors in human–human interaction have been studied in psychology and cognitive science, and the gaze behavior in human–android interaction can be compared to it. Some gaze behaviors are conscious (e.g., people look at one another to coordinate turn-taking [16]) and others are unconscious. This paper focuses on breaking eye contact while thinking, which is one of the unconscious gaze behaviors.

The tendency to break eye contact during a conversation has been studied in psychology. While thinking, people sometimes break eye contact (avert their eyes from the interlocutor). There are three main theories that explain this behavior:

The arousal reduction theory. There is a fact that arousal is the highest when a person makes eye contact during face-to-face communication [17]. This theory suggests that people break eye contact while thinking to reduce their arousal and concentrate on the problem [18].

The differential cortical activation hypothesis. This hypothesis suggests that brain activation induced by thinking tasks leads individuals to shift their gaze away from the central visual field [19].

The social signal theory. This theory suggests that gaze behavior acts as a social signal — people break eye contact to inform others that they are thinking.

If breaking eye contact were a kind of social signal, we would expect it to be influenced by the interlocutor. Psychological researchers have reported that there is experimental evidence to support the social signal theory [20, 21]. We report an experiment that compares subjects' breaking of eye contact with human and android interlocutors.

We hypothesize that if the manner in which eye contact is broken while thinking acts as a social signal, subjects will produce different eye movements if the interlocutor is not human-like or if the subjects do not consider the interlocutor to be a responsive agent. Conversely, if eye movement does not change, it supports the contention that subjects are treating the android as if it were a person or at least a social agent.

3.2. Experiment 1

3.2.1. Procedure

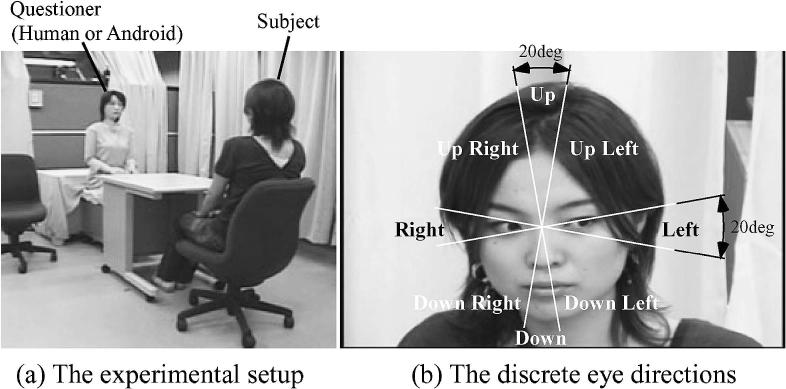

The subjects were made to sit opposite a questioner (Fig. 5a). The subjects' eye movements were measured while they were thinking about the answers to questions posed by the questioner. There were two types of questions: ‘know questions’ and ‘think questions’. The know questions were used as a control condition. Know questions were those to which the subjects already knew the answers (e.g., ‘How old are you?’). Think questions, on the other hand, were those questions to which the subjects did not already know the answers because the subject was compelled to derive the answer (e.g., ‘Please tell me a word that consists of eight letters’).

Figure 5.

The experimental scene and the eight averted gaze directions.

The subjects were asked 10 know questions and 10 think questions in random order. Their faces were videotaped and their gaze direction was coded from the end of the question to the beginning of the answer. The video records of each subject's eye movements were analyzed frame by frame. The average duration of gaze in the eight directions shown in Fig. 5b was then calculated.

Two types of questioners were used: a Japanese person (human questioner) and the android Repliee Q1 (android questioner). In order to make the android appear as human-like as possible, we conducted the experiment of the case of the android questioner in the following manner. A speaker embedded in the android's chest produced a prerecorded voice. In order to make the android appear natural, it was programmed such that it displayed micro-behaviors such as eye and shoulder movements. At first, the experimenter seated beside the android explained the experiment to the subject in order to habituate the subject to the android. During the explanation, the android behaved like an autonomous agent (e.g., it continuously made slight movements of the eyes, head and shoulders, while yawning occasionally). It seemed that the subject actually believed that the android was asking questions autonomously; in reality, however, the questions were being manually triggered by an experimenter seated behind a partition.

The subjects were Japanese adults (six men and six women between 20 and 23 years of age in the case of the human questioner, and four men and four women between 21 and 33 years of age in the case of the android questioner). The subjects to interact with the human questioner were recruited from a university student population and the subjects to interact with the android questioner were recruited from a temporary employment agency. Most of them were unfamiliar with the android. Each subject was asked to read and sign a consent form before the experiment. In order to avoid the subject being asked the same questions, each subject participated in only one case of questioner.

3.2.2. Result

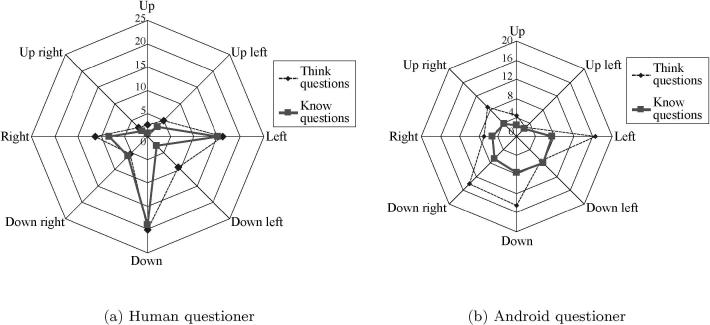

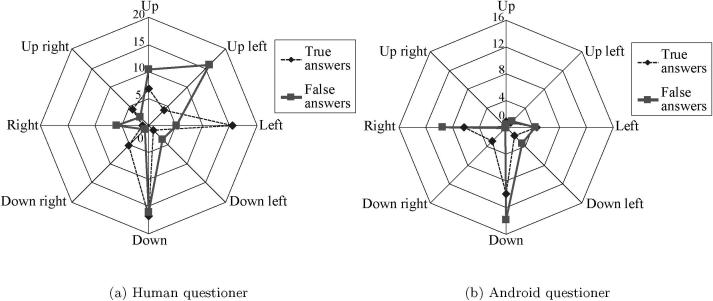

Table 1 shows the average percentage of times that the subjects looked in each eye direction in the case of the human questioner; this has been illustrated by the polar plot in Fig. 6a. In the same manner, Table 2 and Fig. 6b show the results in the case of the android questioner.

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviation of gaze duration (%) in the case of the human questioner (Experiment 1)

| Down right | Down | Down left | Right | Left | Up right | Up | Up left | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Think | Mean | 5.42 | 20.0 | 9.29 | 11.3 | 16.2 | 2.79 | 2.62 | 4.96 |

| SD | 6.73 | 17.3 | 13.1 | 11.4 | 17.3 | 4.36 | 4.66 | 6.37 | |

| Know | Mean | 5.96 | 19.0 | 2.69 | 8.25 | 15.2 | 1.83 | 0.752 | 3.05 |

| SD | 6.43 | 24.8 | 4.07 | 14.5 | 12.8 | 3.40 | 1.87 | 5.76 |

Figure 6.

Average percentage of duration of gaze in eight averted directions (Experiment 1).

Table 2.

Mean and standard deviation of gaze duration (%) in the case of the android questioner (Experiment 1)

| Down right | Down | Down left | Right | Left | Up right | Up | Up left | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Think | Mean | 14.1 | 14.4 | 7.23 | 6.87 | 16.5 | 8.62 | 4.42 | 2.63 |

| SD | 13.8 | 13.9 | 4.41 | 7.89 | 13.3 | 14.2 | 5.93 | 2.26 | |

| Know | Mean | 6.53 | 7.57 | 7.87 | 5.10 | 7.47 | 3.73 | 2.29 | 2.18 |

| SD | 8.26 | 12.0 | 9.77 | 8.47 | 7.41 | 8.36 | 5.73 | 3.47 |

In order to examine the effect of the questioner on the duration of breaking eye contact, a repeated measures three-way ANOVA with one between-subject factor (questioner) and two within-subject factors (question type and eye direction) was conducted. There were significant effects of question type (F(1, 18) = 56.8, P < 0.000001), eye direction (F(7, 126) = 4.28, P < 0.0005) and interaction between questioner and question type (F(1, 18) = 6.41, P < 0.05). No simple main effect of questioner was found. In order to examine the interaction effect, repeated measures two-way question type × eye direction ANOVAs were conducted in the case of both questioner. A significant effect of question type was found (F(1, 112) = 5.74, P < 0.05) in the case of the android questioner; however, no significant effect of question type was found in the case of the human questioner.

As can be seen in Fig. 6a, in the case of the human questioner, subjects tend to avert their eyes downward when a question is asked, even if they are not required to derive the answer. Thus, the averted eye direction does not depend on the question type. It is said that Japanese frequently avoid making eye contact during conversations [22, 23]. Therefore, it may be due to Japanese culture that there is no difference between results of both question types in the case of the human questioner. Meanwhile, for the android questioner, the averted eye direction changes depending on the question type, as can be seen in Fig. 6b. The subjects looked around more frequently for the think questions as compared to the know questions. The subjects' mental state in the case of the android questioner appeared to be different from that in the case of the human questioner. According to our hypothesis, this difference suggests that the subjects consider the android to be a different kind of agent from a person. Experiment 2 was conducted to obtain evidence to support the above inference.

3.3. Experiment 2

In experiment 2, we prepared another situation that required subjects to think about the answer. There is a commonsense belief, known as ‘deceiver stereotype’ [24], in which people who are deceptive avoid eye contact. Some researchers have shown that people use the speaker's eye gaze display to detect and infer deception (e.g., Ref. [25]). It can be inferred that people unconsciously avoid eye contact when they deceive an interlocutor. In the experiment, a questioner posed questions to the subjects, who were told in advance to answer either truthfully or dishonestly. When the subjects were told to answer dishonestly, they had to convince the questioner that they were telling the truth (i.e. they had to deceive the questioner). We measured subjects' eye movements while they were thinking about the answers. We hypothesized that the subjects' gaze behavior would change if they did not treat the android as if it were a person.

3.3.1. Procedure

We conducted an experiment almost identical to that described in Section 3.2.1, except for the fact that in this experiment the subjects were instructed to answer the questions in a particular manner. Before being asked a question, the subjects were shown a cue card on which the word TRUE or FALSE was written by an experimenter seated behind a partition. The questioner could not see the card. If the card had TRUE written on it (true answer), the subjects were instructed to answer the subsequent question truthfully. If the card had FALSE written on it (false answer), they were instructed to answer the subsequent question with a dishonest, but convincing answer. The subjects had to answer five questions truthfully and five questions while lying convincingly. The questions required subjects to provide personal information (e.g., ‘When is your birthday?’); thus, it was impossible for the questioner to know the truth.

The subjects were Japanese adults (five men and six women between 20 and 23 years of age in the case of the human questioner, and six men and 10 women between 21 and 35 years of age in the case of the android questioner). The subjects to interact with the human questioner were the same as those participated in the case of human questioner of Experiment 1 (one subject was removed). The subjects to interact with the android questioner were recruited from a temporary employment agency. Most of them were unfamiliar with the android. Each subject was asked to read and sign a consent form before the experiment. In order to avoid the a subject being asked the same questions, each subject participated in only one case of questioner.

3.3.2. Result

Table 3 shows the average percentage of times that the subjects looked in each eye direction in the case of the human questioner; this is illustrated by the polar plot in Fig. 7a. In the same manner, Table 4 and Fig. 7b show the results in the case of the android questioner.

Table 3.

Mean and standard deviation of gaze duration (%) in the case of the human questioner (Experiment 2)

| Down right | Down | Down left | Right | Left | Up right | Up | Up left | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| True | Mean | 5.22 | 16.7 | 1.12 | 1.07 | 15.4 | 4.04 | 6.81 | 4.02 |

| SD | 8.68 | 18.6 | 3.36 | 2.27 | 13.7 | 11.4 | 10.4 | 6.03 | |

| False | Mean | 0.989 | 16.0 | 3.60 | 6.00 | 5.08 | 2.25 | 10.4 | 15.9 |

| SD | 1.82 | 20.9 | 6.74 | 10.9 | 7.94 | 5.65 | 12.4 | 23.8 |

Figure 7.

Average percentage of duration of gaze in eight averted directions (Experiment 2).

Table 4.

Mean and standard deviation of gaze duration (%) in the case of the android questioner (Experiment 2)

| Down right | Down | Down left | Right | Left | Up right | Up | Up left | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| True | Mean | 2.94 | 9.94 | 1.71 | 6.31 | 4.59 | 0.0682 | 0.941 | 0.878 |

| SD | 6.63 | 14.7 | 6.62 | 13.3 | 7.44 | 0.273 | 2.58 | 2.33 | |

| Flase | Mean | 0.249 | 13.8 | 3.37 | 9.45 | 4.31 | 0.00 | 0.450 | 1.26 |

| SD | 0.859 | 17.6 | 5.49 | 19.3 | 6.63 | 0.00 | 1.23 | 2.95 |

A repeated measures three-way ANOVA with one between-subject factor (questioner) and two within-subject factors (answer type and eye direction) revealed significant effects of questioner (F(1, 25) = 7.21, P < 0.05), eye direction (F(7, 175) = 5.64, P < 0.00001) and interaction between answer type and eye direction (F(7, 175) = 2.72, P < 0.05). In order to examine the interaction effect, repeated measures two-way answer type × eye direction ANOVAs were conducted and no significant effect of answer type was found in the case of both questioners.

As in Experiment 1, the subjects tended to avert their eyes downward when they were asked a question. From the result in Experiment 1, it is predicted that there is a difference in gaze behavior between the two answer types; however, there is no significant difference. This may be because the subjects attempted to show similar reactions in the case of both answer types. Thus, the subjects succeeded in masking their gaze behavior to deceive the questioner.

As can be seen in Fig. 7, contrary to the results obtained in Experiment 1, the subjects looked around more frequently in the case of the human questioner as compared to the case of the android questioner. Daibo and Takimoto [26] have reported that subjects' body motions (e.g., talking and gaze motion) increase when they are required to convince a person of an opinion that is different from their own. They suggested that subjects experience strain or uneasiness due to their deception and their unintentional behavior becomes more apparent. Our results also suggest that subjects experienced a strain when answering the human questioner, but not in the case of the android questioner. The subjects might have believed that the android questioner would be unable to detect their deception. This supports the belief that subjects do not treat the android as if it were a person.

3.4. Summary

In the above experiments, the subjects made unconscious interpersonal responses, i.e. they broke eye contact while thinking, in the case of the android Repliee Q1. This fact suggests that Repliee Q1 is human-like. However, the gaze pattern is different from that in the case of the human questioner. Thus, there still remains an unnaturalness in the communication between the subject and the android.

The difference in gaze behavior with respect to the different questioners suggests that breaking eye contact while thinking is not only induced by brain activity, but also has a social meaning. However, before such evidence can be obtained, it is necessary to compare the gaze behaviors elicited by the android and a person. Furthermore, it was found that the breaking of eye contact could be a response in order to evaluate the android's human likeness. If eye movement in the case of the android questioner is the same as that in interpersonal communication, it is suggested that subjects treat the android as if it were a person or at least a social agent. In order to make the results more convincing, it is necessary to compare these results with those obtained for different questioners, such as more machine-like robots.

4. CONCLUSIONS

This paper proposed a hypothesis about how appearance and behavior are related, and mapped out a plan for android research in order to investigate the hypothesis. The action of breaking eye contact while thinking was considered from the standpoint of the appearance and behavior problem. In the study, we used the android to investigate the sociality of gaze behavior while thinking and obtained evidence that differs from psychological experiments in human studies. Furthermore, it was found that breaking of eye contact could be a measure of an android's human likeness. However, this study is only preliminary and a more comprehensive study is required to explain the results in order to contribute to human psychology.

Acknowledgments

We have developed the android robots Repliee R1, Repliee Q1 and Repliee Q2 in collaboration with Kokoro Company.

Biographies

Takashi Minato obtained his PhD degree in Engineering from Osaka University in 2004. He was a Researcher of CREST, JST since December 2001. He has been an Assistant Professor of the Department of Adaptive Machine Systems, Osaka University since September 2002. He is a member of the Robotics Society of Japan.

Takashi Minato obtained his PhD degree in Engineering from Osaka University in 2004. He was a Researcher of CREST, JST since December 2001. He has been an Assistant Professor of the Department of Adaptive Machine Systems, Osaka University since September 2002. He is a member of the Robotics Society of Japan.

Michihiro Shimada received the BE and ME degrees in Engineering from Osaka University in 2004 and 2006, respectively. He has been on a Doctor course of the Department of Adaptive Machine Systems, Osaka University since April 2006.

Michihiro Shimada received the BE and ME degrees in Engineering from Osaka University in 2004 and 2006, respectively. He has been on a Doctor course of the Department of Adaptive Machine Systems, Osaka University since April 2006.

Shoji Itakura obtained his PhD from Kyoto University (Japan) in 1989 and was a Postdoctoral Fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science at the Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University from 1989 to 1991. He was a Visiting Scientist of Emory University from 1997 to 1998. Since October, 2000, he has been an Associate Professor of the Department of Psychology, Kyoto University (Japan). He studies the comparative development of social cognition and behavior in human and non-human primates. His current work focuses on the development of mentalzing.

Shoji Itakura obtained his PhD from Kyoto University (Japan) in 1989 and was a Postdoctoral Fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science at the Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University from 1989 to 1991. He was a Visiting Scientist of Emory University from 1997 to 1998. Since October, 2000, he has been an Associate Professor of the Department of Psychology, Kyoto University (Japan). He studies the comparative development of social cognition and behavior in human and non-human primates. His current work focuses on the development of mentalzing.

Kang Lee obtained his PhD from the University of New Brunswick (Canada) in 1994, and was a Postdoctoral Fellow at the MRC Cognitive Development Unit (UK) and Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto from 1994 to 1995. He taught in the Department of Psychology, Queen's University (Canada) from 1994 to 2003, first as an Assistant Professor and then an Associate Professor. Between 2003 and 2005, he was an associate professor in the Department of Psychology, University of California, San Diego (USA). Since July 2005 he has been a Professor and Director of the Institute of Child Study at the University of Toronto (Canada). He studies the development of social cognition and behavior. His current work focuses on the development of lying and the development of face and gaze processing.

Kang Lee obtained his PhD from the University of New Brunswick (Canada) in 1994, and was a Postdoctoral Fellow at the MRC Cognitive Development Unit (UK) and Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto from 1994 to 1995. He taught in the Department of Psychology, Queen's University (Canada) from 1994 to 2003, first as an Assistant Professor and then an Associate Professor. Between 2003 and 2005, he was an associate professor in the Department of Psychology, University of California, San Diego (USA). Since July 2005 he has been a Professor and Director of the Institute of Child Study at the University of Toronto (Canada). He studies the development of social cognition and behavior. His current work focuses on the development of lying and the development of face and gaze processing.

Hiroshi Ishiguro received the DE degree from Osaka University, Osaka, Japan, in 1991. In 1991, he started working as a Research Assistant of the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Yamanashi University, Yamanashi, Japan. Then, he moved to the Department of Systems Engineering, Osaka University, as a Research Assistant in 1992. In 1994, he was an Associate Professor in the Department of Information Science, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan, and started research on distributed vision using omnidirectional cameras. From 1998 to 1999, he worked in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of California, San Diego, as a Visiting Scholar. In 2000, he moved to the Department of Computer and Communication Sciences, University, Wakayama, Japan, as an Associate Professor and became a Professor in 2001. He is now a Professor of the Department of Adaptive Machine Systems, Osaka University and a Group Leader at ATR Intelligent Robotics and Communication Laboratories, Kyoto. Since 1999, he has also been a Visiting Researcher at ATR Media Information Science Laboratories, Kyoto, and has developed the interactive humanoid robot, Robovie.

Hiroshi Ishiguro received the DE degree from Osaka University, Osaka, Japan, in 1991. In 1991, he started working as a Research Assistant of the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Yamanashi University, Yamanashi, Japan. Then, he moved to the Department of Systems Engineering, Osaka University, as a Research Assistant in 1992. In 1994, he was an Associate Professor in the Department of Information Science, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan, and started research on distributed vision using omnidirectional cameras. From 1998 to 1999, he worked in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of California, San Diego, as a Visiting Scholar. In 2000, he moved to the Department of Computer and Communication Sciences, University, Wakayama, Japan, as an Associate Professor and became a Professor in 2001. He is now a Professor of the Department of Adaptive Machine Systems, Osaka University and a Group Leader at ATR Intelligent Robotics and Communication Laboratories, Kyoto. Since 1999, he has also been a Visiting Researcher at ATR Media Information Science Laboratories, Kyoto, and has developed the interactive humanoid robot, Robovie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asada M, MacDorman KF, Ishiguro H, Kuniyoshi Y. Cognitive developmental robotics as a new paradigm for the design of humanoid robots. Robotics Autonomous Syst. 2001;37:185–193. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ishiguro H, Ono T, Imai M, Kanda T, Nakatsu R. Robovie: an interactive humanoid robot. Industrial Robot. 2001;28:498–504. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanda T, Ishiguro H, Ono T, Imai M, Mase K. Development and evaluation of an interactive robot ‘Robovie’; Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. on Robotics and Automation; Washington, DC. 2002. pp. 1848–1855. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perrett DI, Oram MW, Ashbridge E. Evidence accumulation in cell populations responsive to faces: an account of generalisation of recognition without mental transformations. Cognition. 1998;67:111–145. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(98)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kendon A. Some functions of gaze-direction in social interaction. Acta Psychologia. 1967;26:22–63. doi: 10.1016/0001-6918(67)90005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Argyle M, Dean J. Eye-contact, distance and affiliation. Sociometry. 1965;28:289–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.French RM. Subcognition and the limits of the Turing Test. Mind. 1990;99:53–65. [Google Scholar]

- 8.French RM. The Turing Test: the first fifty years. Trends Cognitive Sciences. 2000;4:115–121. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01453-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mori M. Bukimi no tani [the uncanny valley] Energy. 1970;7(4):33–35. in Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fong T, Nourbakhsh I, Dautenhahn K. A survey of socially interactive robots. Robotics and Autonomous Systems. 2003;42:143–166. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goetz J, Kiesler S, Powers A. Matching robot appearance and behavior to tasks to improve human-robot cooperation; Proc. IEEE Workshop on Robot and Human Interactive Communication; Silicon Valley, CA. 2003. pp. 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakaoka S, Nakazawa A, Yokoi K, Hirukawa H, Ikeuchi K. Generating whole body motions for a biped humanoid robot from captured human dances; Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. on Robotics and Automation; Taipei. 2003. pp. 3905–3910. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsui D, Minato T, MacDorman KF, Ishiguro H. Generating natural motion in an android by mapping human motion; Proc. IEEE/RSJ Int. Conf. on Intelligent Robot Systems; Edmonton. 2005. pp. 1089–1096. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oztop E, Franklin DW, Chaminade T, Cheng G. Human–humanoid interaction: Is a humanoid robot perceived as a human? Int. J. Humanoid Robotics. 2005;2:537–559. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minato T, Shimada M, Ishiguro H, Itakura S. Development of an android robot for studying human-robot interaction; Proc. 17th Int. Conf. on Industrial and Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence and Expert Systems; Ottawa. 2004. pp. 424–434. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kendon A. Looking in conversations and the regulation of turns at talk: A comment on the papers of G. Beattie and D. R. Rutter et al. Br. J. Social Clin. Psychol. 1978;17:23–24. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gale A, Kingsley E, Brookes S, Smith D. Cortical arousal and social intimacy in the human female under different conditions of eye contact. Behav. Process. 1978;3:271–275. doi: 10.1016/0376-6357(78)90019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Argyle M, Cook M. Gaze and Mutual Gaze. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Previc FH, Murphy SJ. Vertical eye movements during mental tasks: A reexamination and hypothesis. Percept. Motor Skills. 1997;84:835–847. doi: 10.2466/pms.1997.84.3.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCarthy A, Lee K, Muir D. Eye gaze displays that index knowing, thinking and guessing; poster presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Society; Toronto, Ontario. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCarthy A, Muir D. Eye movements as social signals during thinking: age differences; poster presented at the Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Tampa, FL. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kagawa H. The Inscrutable Japanese (Kodansha Bilingual Books) Kodansha International; Tokyo: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishiyama K. Doing Business with Japan: Successful Strategies for Intercultural Communication. University of Hawaii Press; Honolulu, HI: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leathers DG. Successful Nonverbal Communication: Principles and Applications. 3rd edn. Allyn & Bacon; Boston, MA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hemsley GD, Doob NA. The effect of looking behavior on perceptions of a communicator's credibility. J. Appl. Social Psychol. 1978;8:136–144. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daibo I, Takimoto T. Deceptive characteristics in interpersonal communication. J. Jpn Exp. Social Psychol. 1992;32:1–14. in Japanese. [Google Scholar]