Abstract

Background

Classical Salmonella serotyping is an expensive and time consuming process that requires implementing a battery of O and H antisera to detect 2,541 different Salmonella enterica serovars. For these reasons, we developed a rapid multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based typing scheme to screen for the prevalent S. enterica serovars Enteritidis, Hadar, Heidelberg, and Typhimurium.

Results

By analyzing the nucleotide sequences of the genes for O-antigen biosynthesis including wba operon and the central variable regions of the H1 and H2 flagellin genes in Salmonella, designated PCR primers for four multiplex PCR reactions were used to detect and differentiate Salmonella serogroups A/D1, B, C1, C2, or E1; H1 antigen types i, g, m, r or z10; and H2 antigen complexes, I: 1,2; 1,5; 1,6; 1,7 or II: e,n,x; e,n,z15. Through the detection of these antigen gene allele combinations, we were able to distinguish among S. enterica serovars Enteritidis, Hadar, Heidelberg, and Typhimurium. The assays were useful in identifying Salmonella with O and H antigen gene alleles representing 43 distinct serovars. While the H2 multiplex could discriminate between unrelated H2 antigens, the PCR could not discern differences within the antigen complexes, 1,2; 1,5; 1,6; 1,7 or e,n,x; e,n,z15, requiring a final confirmatory PCR test in the final serovar reporting of S. enterica.

Conclusion

Multiplex PCR assays for detecting specific O and H antigen gene alleles can be a rapid and cost-effective alternative approach to classical serotyping for presumptive identification of S. enterica serovars Enteritidis, Hadar, Heidelberg, and Typhimurium.

Background

There are approximately 15 cases of salmonellosis per 100,000 persons annually in the United States, more than double the 2010 Healthy People goal of 6.8 cases/100,000 individuals per year [1]. In order to reduce human illnesses, epidemiological measures have been implemented to reduce the source(s) of infection. Because food animals and poultry are recognized as important reservoirs of Salmonella [2,3], the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Food Safety Inspection Service (FSIS) implemented an "in plant" Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) program to reduce the prevalence of foodborne pathogen contamination in meats, eggs, and milk. Although in-plant HACCP programs have been successful, further reductions in Salmonella contamination may require application of a risk reduction strategy to the farm environment. On-farm control programs have been effective in the past when they have been directed against vertically-transmitted S. enterica serovars (such as S. enterica serovar Enteritidis and S. enterica serovar Gallinarum) [4], but it is unclear whether this approach could be effective against all serovars. A more achievable goal may be to mitigate those S. enterica serovars that are most frequently associated with severe human illness. To further reduce Salmonella contamination in or on the final food product, producers may need to reduce its prevalence in animals brought into the meat processing plant. Producers may also need to accurately identify the source of Salmonella within a specific setting, in order to identify the points where an intervention [5] may be effective. Such an approach would require knowing whether these serovars are present on the farm. Also, determining the appropriate S. enterica serovar is a necessary first step in any epidemiological investigation of foodborne outbreaks; followed then by strain typing, using molecular based methods including pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) [6] or amplified fragment length polymorphism that is needed to match patient strain to source [7]. Serotyping can be a formidable task because of the numerous antisera required and the expertise necessary for interpreting the agglutination reactions, thereby limiting its efficacy as a large scale screening tool.

There are currently 2,541 S. enterica serovars recognized based on antigenic differences in the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) O-antigen; and phase 1 (H1) and phase 2 (H2) flagellar antigens [8]. Salmonella can be further separated into monophasic and biphasic based on whether they express only one (H1) or both flagellar antigens (H1 and H2). The antigenic formula 4,5,12 (O): i (H1): 1,2 (H2) is the biphasic S. enterica serovar Typhimurium and 1,9,12 (O):g,m (H1):- (no H2) identifies the monophasic S. enterica serovar Enteritidis. Among the 2,541 S. enterica serovars identified to date, 10 S. enterica serovars: Typhimurium, Enteritidis, Newport, Heidelberg, Javiana, 4, [5], 12:i:-, Montevideo, Muenchen, Saintpaul, and Braenderup, currently account for 66% of all cases of laboratory-confirmed salmonellosis in the U.S. [8]. Between 1998–2006, S. enterica serovars Enteritidis, Hadar, Heidelberg, and Typhimurium also accounted for 48% of all S. enterica serovars isolated from poultry, including chicken broilers, ground chicken and ground turkey, in the U.S. [9]. Worldwide, two serovars, Enteritidis and Typhimurium are responsible for 79% of reported cases of salmonellosis [10].

Salmonella serotyping is based on the identification of the variable O and H antigens. Because the antigenic composition of the O, H1 and H2 antigens are a reflection of their unique DNA sequence alleles [11,12], PCR and similar nucleotide-based methods have made it possible to accelerate the identification of serotypes based upon the identification of unique genes or gene arrangements [13-18] and use as a diagnostic tool [19]. We report here on the development and validation of a serologically-correlative PCR-based assay that could solve a number of the logistical challenges faced by diagnostic and food microbiology labs.

Results and discussion

Multiplex PCR differentiation of Salmonella enterica serovars Enteritidis, Hadar, Heidelberg, and Typhimurium

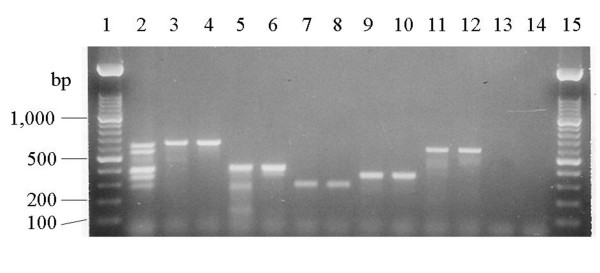

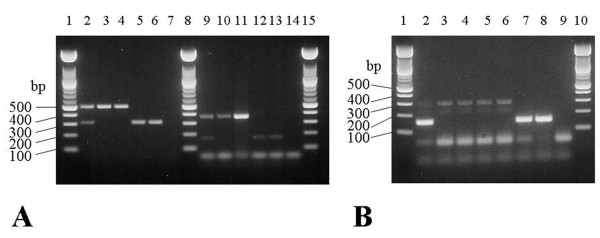

We developed multiplex PCRs targeted to the O, H1, and H2 alleles associated with four S. enterica serovars Enteritidis, Hadar, Heidelberg, and Typhimurium. Specific PCR primers to identify specific Salmonella serogroups, H1 and H2 alleles were designed based on the divergence of the glycosyl synthase genes, the unique linkage between two genes for a specific O-antigen of Salmonella, or allele-specific sequences within the hypervariable region of H1 and H2 antigen genes. In the primer design, a unique amplicon size was selected in order to facilitate development of a multiplex PCR (Table 1, Fig. 1 &2). The ability of the multiplex PCR to correctly identify serogroups (Fig. 1) was evaluated for 239 Salmonella isolates representing forty-three different serotypes which belonged to one of the six major serogroups, A, B, C1, C2, D1 and E1. With the exception of serogroups A and D1, which produce the same size amplicons (Kappa = 0.98), the multiplex PCR accurately distinguished salmonellae belonging to serogroups B, C1, C2, and E1 (Kappa = 1.00) (Table 2). The inability to distinguish serogroups A and D1 is due to the high degree of nucleotide sequence homology between the prt (paratose synthase) genes [20]. The fliC multiplex PCRs successfully detected the H1, i, r, or z10, alleles (Fig. 2A) and no amplicons were produced for serovars with other H1, flagellins (Kappa = 1.00) (Table 2). However, the fliC g,m primer set produced the same size amplicon only for salmonellae that possessed both the g and m, or g alone, or either epitope, g or m, in combination with other serotype-specific epitopes, or non-motile salmonellae that possess the fliC g,m allele [21] and therefore it did not have the specificity of the other H1 primer sets (Kappa = 0.58 vs. 1.00) (Table 2). To complement our PCR-based H allelotyping, a fljB multiplex PCR was designed to detect the H2 antigen alleles by targeting conserved regions within fljB alleles encoding the antigen complexes I: 1,2; 1,5; 1,6; 1,7 or II: e,n,x; e,n,z15 and producing unique size amplicons (Table 1, Fig. 2B). The expected size amplicons were produced for only those S. enterica serovars belonging to H2 antigen complexes I: 1,2; 1,5; 1,6: 1,7 and. II: e,n,x; e,n,z15 (Fig. 2B). The H2 multiplex PCR however could not distinguish H2 1,2 allele (Kappa = 0.75) or e,n,x (Kappa = 0.54) among the different H2 alleles within each antigen complex; for example indistinguishable amplicons were produced for Salmonella isolates bearing 1,2 vs 1,5; 1,6; or 1,7 (Table 2).

Table 1.

Primers used for multiplex PCR to detect and differentiate Salmonella enterica serogroups and serovars

| Target gene1 | Nucleotide sequence | Expected Size (bp) |

| O-antigen multiplex | ||

| abe1 (B) | F: GGCTTCCGGCTTTATTGG | 561 |

| R: TCTCTTATCTGTTCGCCTGTTG | ||

| wbaD-manC (C1) | F: ATTTGCCCAGTTCGGTTTG | 341 |

| R: CCATAACCGACTTCCATTTCC | ||

| abe2 (C2) | F: CGTCCTATAACCGAGCCAAC | 397 |

| R: CTGCTTTATCCCTCTCACCG | ||

| prt (A/D1) | F: ATGGGAGCGTTTGGGTTC | 624 |

| R: CGCCTCTCCACTACCAACTTC | ||

| wzx – wzy (E1) | F: GATAGCAACGTTCGGAAATTC | 281 |

| R: CCCAATAGCAATAAACCAAGC | ||

| H1-1 multiplex | ||

| fliC (i) | F: AACGAAATCAACAACAACCTGC | 508 |

| R: TAGCCATCTTTACCAGTTCCC | ||

| fliC (g,m) | F: GCAGCAGCACCGGATAAAG | 309 |

| R: CATTAACATCCGTCGCGCTAG | ||

| H1-2 multiplex | ||

| fliC (r) | F: CCTGCTATTACTGGTGATC | 169 |

| R: GTTGAAGGGAAGCCAGCAG | ||

| fliC (z10) | F: GCACTGGCGTTACTCAATCTC | 363 |

| R: GCATCAGCAATACCACTCGC | ||

| H2 multiplex | ||

| fljB (I: 1,2; 1,5; 1,6; 1,7) | F: AGAAAGCGTATGATGTGAAA | 294 |

| R: ATTGTGGTTTTAGTTGCGCC | ||

| fljB (II: e,n,x; e,n,z15) | F: TAACTGGCGATACATTGACTG | 152 |

| R: TAGCACCGAATGATACAGCC | ||

1Indicates the unique genes or the junctions between the two genes used for designing PCR primers. () = antigen(s) detected.

Figure 1.

Multiplex PCR for identifying serogroup-specific, Salmonella O antigen biosynthesis gene(s). Lanes1 and 15: 100 bp MW standard; lane 2, multiplex PCR control for five Salmonella serogroups; lane 3: S. enterica serovar Paratyphi A [A]; lane 4: S. enterica serovar Enteritidis [D1]; lane 5: S. enterica serovar Muenchen [C2]; lane 6: S. enterica serovar Hadar [C2]; lane 7: S. enterica serovar Anatum [E1]; lane 8: S. enterica serovar London [E1]; lane 9: S. enterica serovar Infantis [C1]; lane 10: S. enterica serovar Tennessee [C1]; lane 11: S. enterica serovar Saintpaul [B]; lane 12, S. enterica serovar Typhimurium [B]; lane 13: E. coli K12 LE392, negative control; and lane 14: no DNA control. The sizes of the PCR amplicons are 624 bp for serogroup A/D1, 561 bp for serogroup B, 341 bp for serogroup C1, 397 bp for serogroup C2, and 281 bp for serogroup E1.

Figure 2.

Multiplex PCR for identifying Salmonella H1 and H2 gene alleles. (a) Multiplex PCR for identifying H1 antigen gene alleles: i, g,m, r, and z10. Lanes 2–7: H1-1 multiplex PCR for i and g,m antigens. Lanes 9–14: H1-2, multiplex PCR for antigens r and z10. Lanes 1, 8, and 15: 100 bp MW standard; lane 2: H1-1 multiplex PCR control; lane 3: S. enterica serovar Typhimurium [i]; lane 4: S. enterica serovar Kentucky [i]; lanes 5 and 6: S. enterica serovar Enteritidis [g,m]; lane 7: no DNA control; lane 9: H1-2 multiplex PCR control; lane 10: S. enterica serovar Hadar [z10]; lane 11: S. enterica serovar Mbandaka [z10]; lane12: S. enterica Heidelberg [r]; lane 13: S. enterica serovar Infantis [r]; and lane 14: no DNA control. The sizes of the PCR amplicons are: 508 bp for i, 309 bp for g,m, 169 bp for r, and 363 bp for z10. (b) Multiplex PCR for identifying H2 antigen complexes I: 1,2, 1,5, 1,6, 1,7 and II: e,n,x, e,n,z15 respectively. Lanes 1 and 10: 100 bp MW standard; lane 2: multiplex PCR control for H2 antigen complexes I: 1,2; 1,5; 1,6; 1,7 and II: e,n,x; e,n,z15; lane 3: S. enterica serovar Typhimurium [1,2]; lane 4: S. enterica serovar Infantis [1,5]; lane 5: S. enterica serovar Anatum [1,6]; lane 6, S. enterica serovar Bredeney [1,7]; lane 7: S. enterica serovar Hadar [e,n,x]; lane 8: S. enterica serovar Mbandaka [e,n,z15]; and lane 9: no DNA control. The sizes of the PCR amplicons are 294 bp for H2 antigen complex I: 1,2; 1,5; 1,6; 1,7 and 152 bp for H2 antigen complex II: e,n,x and e,n,z15.

Table 2.

Comparison of multiplex PCR to serotyping for identifying Salmonella O alleles B; C1; C2; D1 or E1; H1 alleles i; g,m; r or z10;and H2 alleles 1,2 or e,n,x

| Phase 1 PCRs | Phase 2 multiplex PCR | ||||||||||||||

| Antigenic Formula | O muliplex PCR | i/g,m multiplex PCR | r/z10multiplex PCR | ||||||||||||

| O | H1 | H2 | S. enterica Serovars | Animal Origin (n)1 | B | C1 | C2 | D1 | E1 | i | g,m | r | z10 | 1,2 | e,n,x |

| A | a | 1,5 | Paratyphi A | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| B | b | 1,2 | Paratyphi B | 1 (1) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| B | e,h | 1,2 | Saintpaul | 1(1) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| B | e,h | 1,5 | Reading | 1(2) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| B | f,g | - | Derby | 1(1) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B | i | 1,2 | Typhimurium | 1, 4–6 (74) | 74 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 74 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 74 | 0 |

| B | l,v | 1,7 | Bredeney | 1(1) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| B | 1,v | e,n,z15 | Brandenburg | 1(2) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| B | b | - | Java | 6(1) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B | e,h | e,n,x | Chester | 1(2) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| B | f,g,s | - | Agona | 1 (1) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B | r | 1,2 | Heidelberg | 1, 3–6(24) | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 24 | 0 |

| B | z | 1,5 | Kiambu | 1(1) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| B | z | 1,7 | Indiana | 1(2) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| B | z10 | 1,2 | Haifa | 6 (1) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| C1 | b | l,w | Ohio | 1(1) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C1 | c | 1,5 | Choleraesuis | 1, 6(6) | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| C1 | c | 1,5 | Paratyphi C | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| C1 | d | l,w | Livingstone | 6(1) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C1 | g,m,s | - | Montevideo | 1, 5(12) | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C1 | k | 1,5 | Thompson | 1(1) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| C1 | m,t | - | Oranienburg | 1(1) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C1 | z29 | - | Tennessee | 1(1) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C1 | e,h | e,n,z15 | Braenderup | 1(2) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| C1 | r | 1,5 | Infantis | 1(2) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| C1 | z10 | e,n,z15 | Mbandaka | 1(14) | 0 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 14 |

| C1 | z28 | - | Lille | 1(1) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C2 | d | 1,2 | Muenchen | 5(3) | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| C2 | e,h | 1,2 | Newport | 4,5(1) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| C2 | i | z6 | Kentucky | 1(24) | 0 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C2 | z10 | e,n,x | Hadar | 1 (10) | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 |

| D1 | a | 1,5 | Miami | 5(1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| D1 | a | 1,5 | Sendai | 5(1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| D1 | g,m | - | Enteritidis | 1(20) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| D1 | g,p | - | Dublin | 2, 6(3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| D1 | l,v | 1,5 | Panama | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| D1 | - | - | Gallinarum | 1(4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| D1 | f,g,t | - | Berta | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| D1 | l,z28 | 1,5 | Javiana | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| E1 | e,h | 1,5 | Muenster | 1(2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| E1 | l,v | 1,7 | Give | 1(2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| E1 | e,h | 1,6 | Anatum | 1, 5 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| E1 | l,v | 1,6 | London | 1(2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Total | 239 | 114 | 43 | 38 | 34 | 10 | 98 | 44 | 26 | 25 | 135 | 30 | |||

| False Positives | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 18 | ||||

| False Negatives | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Kappa2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.98 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.58 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.75 | 0.54 | ||||

11 = poultry; 2 = bovine; 3 = swine, 4 = other (includes dog, heron, horse, opossum, parrot, rabbit, and snake); 5 = human; and 6 = unknown. Numbers in parentheses indicate the numbers of isolates for each serovar.

2Agreement between PCR allelotyping and conventional serotyping results

Comparison of multiplex PCR allelotyping of O, H1, and H2 genes with conventional serotyping in differentiating S. enterica serovars Enteritidis, Hadar, Heidelberg and Typhimurium

Validation of the allelotyping method is important for its integration with conventional Salmonella culture and typing methods used in diagnostic and food microbiology [22-25]. We therefore assessed the allelotyping multiplex PCR against the standard conventional Salmonella serotyping method in identifying Salmonella O, H1 and H2 antigens for 43 different serovars of salmonellae isolated mainly from chicken carcasses and poultry environments (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 3.

Allelotyping PCR scheme for presumptive identification of S. enterica serovars Enteritidis, Hadar, Heidelberg, and Typhimurium

| O-multiplex | H1-multiplexes1 | H2-multiplex | Serovars | Sensitivity5 | Specificity5 |

| B | i | I2 | Typhimurium | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| B | r | I | Heidelberg | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| C2 | z10 | II3 | Hadar | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| A/D1 | g,m | -4 | Enteritidis | 1.00 | 0.96 |

1Identifies H1 alleles i; g,m; r; or z10

2 Covers H2 alleles 1,2; 1,5; 1,6; and 1,7

3 Covers H2 alleles e,n,x and e,n,z15

4 PCR negative for H2-multiplex

5Sensitivity and specificity of the allelotyping PCR scheme relative to conventional serotyping in identifying S. enterica serovars Enteritidis, Hadar, Heidelberg, and Typhimurium among the 239 isolates examined in this study.

The allelotyping PCR scheme for identifying S. enterica serovars Enteritidis, Hadar, Heidelberg and Typhimurium is envisioned to work as follows. An initial multiplex PCR is performed to determine which O antigen allele that an isolate possesses and a serogroup designation is given or unknown, based on PCR results. If the isolate possesses O alleles for serogroups B, C2, or A/D1, then a 2nd allelotyping PCR is done to determine the presence of H2 alleles: i; g,m; r; or z10. Based on the results of this 2nd allelotyping PCR, an H1 allele type can be given an isolate as either being i; g,m; r; z10 or unknown, if no amplicons with the expected size for the H1 allelotyping PCR are produced. If both O and H1 allelotyping PCR detects O and H1 alleles associated with S. enterica serovars Enteritidis, Hadar, Heidelberg, and Typhimurium, then a 3rd final H2 allelotyping PCR is performed to further differentiate the isolate to serovar level. Therefore, identifying one allele for each O, H1, and H2 allelotyping PCR, as listed in Table 3; it is possible to discern the serovar for isolates typed using this PCR-based scheme. For example, identification of serogroup B, H1 i, and H2 I antigen complex by multiplex PCR presumptively identifies the isolate as S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (Sensitivity = 1.00; Specificity = 1.00) (Table 3). The expansion of O-antigen PCR to detect serogroups C1 and E1, affords a laboratory the opportunity to detect other S. enterica serovars, as the antigenic formula for O, H1 and H2 antigens defines the serovar. Therefore, we were able to identify additional S. enterica serovars with our multiplex PCRs including Haifa [B; z10; 1,2], Infantis [C1; r; 1,5], and Mbandaka [C1; z10, e,n,z15]. We can also identify monophasic S. enterica serovars (ex. Montevideo: [C1; g,m,s; -]) by including a generic Salmonella fljB (H2) PCR test [14]. Isolates negative for O, H1, and H2 alleles by our multiplex PCR screen would need to be characterized by traditional serotyping, RFLP PCR [14], or PCR screens that identify the other H1 and H2 alleles [15,16,22]. The limitations with our multiplex PCR are that it cannot distinguish among serogroup/serovar variants that arise due to phage conversion and the resulting chemical/antigenic alteration of the somatic O antigen [8] (ex. Hadar vs. Istanbul), or subtle point mutations in H2 antigen gene, fljB responsible for loss of flagellar expression observed in some S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains [26]. Our multiplex PCRs were designed to be used as a rapid screen for S. enterica serovars: Enteritidis, Hadar, Heidelberg, and Typhimurium, targeting key genes/alleles that differentiate these serovars from the rest. As a diagnostic test, our allelotyping PCR was also designed to minimize the cost of this test to a few individual PCR tests, with a minimum number of primers needed for this typing scheme. Unfortunately, our H2 multiplex PCR cannot discern differences within the H2 antigen complexes (Table 2) to make a definitive serovar designation for S. enterica serovars with the same O and H1 antigens as our target serovars (S. enterica serovars: Typhimurium [H2: 1,2] vs. Lagos [H2: 1,5]; Heidelberg [H2: 1,2] vs. Bradford [H2: 1,5], Winneba [H2: 1,6] or Remo [H2: 1,7]; or Hadar [H2: e,n,x] vs. Glostrup [H2: e,n,z15]). Also, the allelotyping primers for H1 g,m allele identifies those H1 alleles bearing g or m in any possible combination (Table 2), therefore H1 multiplex would not be able to discern serogroup D1, S. enterica serovars Enteritidis [H1: g,m] from Blegdam [g,m,q]. While the possibility of encountering these alternate serovars may be remote based on epidemiological data [8,9], it is still a possibility, and where a reporting laboratory may require confirmatory testing there are additional PCR based tests that can discern these allelic differences to make a final, definitive serovar designation possible [15,16]. Alternatively, the H2 amplicons can be sequenced to definitively identify the H2 allele. Although several multiplex PCRs have been developed to assist laboratories in identification of S. enterica serovars [15-17,22], our results are the first to focus on, validate and describe a PCR-based scheme for assisting diagnostic labs in differentiating S. enterica serovars: Enteritidis, Hadar, Heidelberg, and Typhimurium.

Conclusion

The conventional Salmonella serological serotyping scheme is a time-consuming, labor-intensive and expensive procedure. With this PCR based allelotyping scheme, specific S. enterica serovars can be differentiated rapidly. The method is cost-effective and needs little technical training. This multiplex PCR allows large service laboratories to rapidly identify S. enterica serovars of public health importance including Enteritidis, Hadar, Heidelberg, and Typhimurium and focus conventional efforts towards identification of unusual serovars.

Methods

Bacterial strains

The S. enterica isolates used in this study were from multiple animal species, including human, poultry, livestock and wildlife [27-30], and serotyped by the National Veterinary Service Laboratory (NVSL; Ames, IA) using classical methods (Table 2). The isolates were used to test the specificity of PCRs specific for O, H1 and H2 alleles described in Table 1. Additional Salmonella isolates of unknown serovars were obtained from two poultry farms in northeast Georgia [25,31] as well as salmonellae isolated from routine submissions to the Poultry Diagnostic and Research Center (PDRC) in Athens, GA.

Isolation and serotyping of Salmonella

We sampled the commercial chicken broiler house environment and chicken carcasses for Salmonella as previously described [31]. The processing, enrichment, isolation and final diagnostic confirmation of Salmonella from samples is described in detail elsewhere [31]. Serotyping was done using standard serological typing procedures for Salmonella O, H1 and H2 antigens [32].

PCR primer design

From comparative analysis of the wba operon for Salmonella serogroups A/D1, B, C1, C2, and E1 [20,33-37] we identified serogroup-specific gene(s) (National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Accession #: M29682, X56793, X61917, M84642, X60665) for PCR primer design. Similarly, we identified from an alignment within the central variable region [11,38,39] of fliC (H1) and fljB (H2) alleles (NCBI accession #: D13689, M84974, AF15949, AF332601, U06199, U06206, U06225, U06197, M84973, Z15086, D78639, Z15071, Z15072, Z15069, U06205, U06204, AF420426, AF420425, AF045151, U17175, U17171, U17172, AF425736, AF425737), using the DNA analysis software AlignPlus® version 3.0 (Scientific and Educational Software), candidate sequences to differentiate Salmonella with the H1 flagellin antigens i, g,m, r, z10, and the H2 flagellin antigen complexes 1,2, 1,5, 1,6, 1,7 and e,n,x, e,n,z15 alleles. We analyzed these gene sequences, using the GeneRunner® (Hastings software; Hastings, NY) DNA analysis software, and identified suitable primer sets that were compatible in a single multiplex PCR reaction and designed to produce an amplicon with size unique for the sequence(s) targeted by a specific primer set (Table 1).

Multiplex allelotyping PCR for Salmonella O, H1, and H2 antigen genes and differentiating S. enterica serovars Enteritidis, Hadar, Heidelberg, and Typhimurium

The O-antigen multiplex PCR was designed to detect serogroup A/D1, B, C1, C2, or E1 specific genes or alleles (Table 1). The O-antigen multiplex PCR was performed using the Amplitron II Thermolyne thermocycler (Barnstead; Dubuque, IA), using HotStart PCR tubes (Molecular Bio-Products, Inc., San Diego, CA). Each reaction had a final concentration of 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.3, 0.25 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 0.5 μM primer, 0.2 mM deoxynucleotides (Boehringer Mannheim; Indianapolis, IN), 0.5 units of Taq DNA polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim), and 1 μl of whole cell template. The PCR was performed with pre-amplification heating as described by D'Aquilla et al. [40]. The program parameters for PCR include an initial five minutes incubation at 85°C, to mix the two PCR reaction mixes, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 1 min), annealing (55°C for 1 min), and extension (72°C for 1 min). Amplicons were separated on 1.5% agarose gel with Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer [41] and ethidium bromide (0.2 μg/ml) at 100 V. The 100-bp ladder (GIBCO/BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) was used as a molecular weight (MW) standard for determining the MW of the PCR products. Various S. enterica serovars belonging to serogroups A/D1, B, C1, C2, E1 were used in the PCR to test the specificity of the primer sets.

The H1-1 multiplex PCR was used to identify isolates with antigens i or g, m; while the H1-2 multiplex PCR was designed to detect isolates with antigens r or z10. Finally, the H2 multiplex PCR was created to differentiate isolates with either H2 antigen complexes 1,2; 1,5; 1,6; 1,7; or e,n,x; e,n,z15. In order to identify the H1 and H2 alleles, capillary PCR reaction was performed to amplify the alleles of fliC and fljB by three multiplex PCRs with the Rapidycler™ hot-air thermocycler (Idaho Technologies; Idaho Falls, ID) [42] in 10-μl capacity capillary tubes. We sought to reduce the expense of reagents and reaction time by utilizing a capillary thermocycler that accommodates very low reaction volumes. The 10-μl PCR mix for the fliC i and g,m multiplex consisted of 2.0 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Tris (pH 8.3), 0.25 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 0.5 μM of each primer, 0.2 mM deoxynucleotides, 5% DMSO, 1.0 units of Taq DNA polymerase, and 1 μl whole cell template. For fliC r and z10 multiplex, 3.0 mM MgCl2 and 1.0 μM of each primer were used for each reaction. For the amplification of the H2 alleles, the fljB multiplex consisted of 3.75 mM MgCl2, 62.5 mM Tris, pH 8.3, 0.31 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 0.5 μM of each primer, 0.2 mM deoxynucleotides, 5% DMSO, 1.0 units of Taq DNA polymerase, and 1 μl whole cell template in a 10 μl volume. The program parameters for the hot-air thermocycler were an initial heating step of 94°C for 1 min; 94°C for 1 sec, 55°C for 1 sec, and 72°C for 20 sec with a slope of 2.0 for 40 cycles; and a final extension at 72°C for 4 min. Amplicons were detected as described above. The specificity of the PCR detection was tested against various Salmonella serovars possessing the relevant fliC and fljB alleles (Table 2). Escherichia coli LE392 served as a negative control. Whole cell template for all multiplex PCRs was prepared according to the procedures of Hilton et al. [43].

Statistics

Kappa statistics were calculated to evaluate the agreement between the classical serotyping systems and multiplex PCR for each of the antigen groups examined. Sensitivity and specificity of the allelotyping PCR scheme relative to conventional serotyping was calculated for S. enterica serovars Enteritidis, Hadar, Heidelberg, and Typhimurium.

Abbreviations

CDC: Center for Disease Control and Prevention; FSIS: Food Safety Inspection Service; HACCP: Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point; NCBI: National Center for Biotechnology Information; NPIP: National Poultry Improvement Plant; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; PFGE: pulsed-field gel electrophoresis; RFLP: restriction fragment polymorphism; SNP: single nucleotide polymorphism; USDA: United States Department of Agriculture.

Authors' contributions

JJM designed, directed, and supervised most aspects of this project. YH designed, and optimized the multiplex PCRs described in this study, as well as wrote the first draft of this manuscript. MDL and CH were involved in translation of these molecular tests to the diagnostic lab. CH was instrumental in our access to poultry farms and companies to obtain samples/isolates for testing. TL assessed the multiplex PCR in identifying S. enterica serovars for isolates submitted to the PDRC diagnostic lab. MDL and DW were involved in instruction, supervision, and interpretation of classical serotyping. MM and SA assisted in conventional serotyping of isolates. LW did statistical analyses of PCR vs. classical serotyping. RB evaluated and interpreted the statistical tests. MM, TL, and SA roles in this study were beyond those normally associated with their jobs and the University of Georgia or FDA. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

USDA NRICGP grant 99-35212-8680, USDA Formula Funds, and the State of Georgia's Veterinary Medicine Agricultural Research Grant supported this work. We thank Dr. Douglas Waltman for his helpful comments and advice.

Contributor Information

Yang Hong, Email: yang.hong@primuslabs.com.

Tongrui Liu, Email: jmaurer@uga.edu.

Margie D Lee, Email: mdlee@uga.edu.

Charles L Hofacre, Email: chofacre@uga.edu.

Marie Maier, Email: jmaurer@uga.edu.

David G White, Email: david.white@fda.hhs.gov.

Sherry Ayers, Email: sherry.ayers@fda.hhs.gov.

Lihua Wang, Email: yang.hong@primuslabs.com.

Roy Berghaus, Email: berghaus@uga.edu.

John J Maurer, Email: jmaurer@uga.edu.

References

- Vugia D, Cronquist A, Hadler J, Tobin-D'Angelo M, Blythe D, Smith K, Lathrop S, Morse D, Cieslak P, Jones T, Holt KG, Gruzewich JJ, Scallan E, Angulo FJ, Griffin PM, Tauxe RV, Greene SK. Preliminary FoodNet data on the incidence of infection with pathogens transmitted commonly through food-10 states, 2006. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 2007;56:336–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson S. Estimating the incidence of food-borne Salmonella and the effectiveness of alternative control measures using the Delphi method. Int J Food Microbiol. 1997;35:195–204. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(96)01235-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Painter J, Woodruff R, Braden C. Surveillance for foodborne-disease outbreaks-United States, 1998–2002. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 2006:1–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous National Poultry Improvement Plan and Auxiliary Provisions. Code of Federal Regulations. 2007;9:1–153. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez S, Hofacre CL, Lee MD, Maurer JJ, Doyle MP. Animal sources of salmonellosis in humans. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2002;221:492–497. doi: 10.2460/javma.2002.221.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerner-Smidt P, Hise K, Kincaid J, Hunter S, Rolando S, Hyytia-Trees E, Ribot EM, Swaminathan B, PulseNet Taskforce. PulseNet USA: a five-year update. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2006;3:9–19. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2006.3.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstedt BA, Heir E, Vardund T, Kapperud G. Fluorescent amplified-fragment length polymorphism genotyping of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovars and comparison with pulsed-field gel electrophoresis typing. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1623–1627. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.4.1623-1627.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmonella Surveillance Annual Summary. 2005. http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dbmd/phlisdata/salmtab/2005/SalmonellaAnnualSummary2005.pdf

- Serotype Profile of Salmonella from Meat and Poultry http://www/fsis.usda.gov/PDF/Serotypes_Profile_Salmonella_Tables_&_Figures.pdf

- WHO Global Salmonella Survey, Progress Report http://www.who.int/salmsurv/links/GSSProgressReport2005.pdf

- Joys TM. The covalent structure of the phase-1 flagellar filament protein of Salmonella typhimurium and its comparison with other flagellins. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:15758–15761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel G, Reeves P. Biosynthesis of O-antigens: genes and pathways involved in nucleotide sugar precursor synthesis and O-antigen assembly. Carbohydr Res. 2003;338:2503–2519. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2003.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curd H, Liu D, Reeves PR. Relationships among the O-antigen gene clusters of Salmonella enterica groups B, D1, D2, and D3. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1002–1007. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.4.1002-1007.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauga C, Zabrovskaia A, Grimont PAD. Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of some flagellin genes of Salmonella enterica. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2835–2843. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.2835-2843.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echeita MA, Herrera S, Garaiznar J, Usera MA. Multiplex PCR-based detection and identification of the most common Salmonella second-phase flagellar antigens. Res Microbiol. 2002;153:107–113. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(01)01295-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echeita MA, Usera MA. Rapid identification of Salmonella spp. phase 2 antigens of the H2 antigenic complex using "multiplex PCR". Res Microbiol. 1998;149:757–761. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(99)80022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk JMC, Kongmuang U, Reeves PR, Lindberg AA. Selective amplification of abequose and paratose synthase genes (rfb) by polymerase chain reaction for identification of Salmonella major serogroups (A, B, C2, and D) J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2118–2123. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.8.2118-2123.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer JJ, Schmidt D, Petrosko P, Sanchez S, Bolton L, Lee MD. Development of primers to O-antigen biosynthesis genes for specific detection of Escherichia coli O157 by PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:2954–2960. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.7.2954-2960.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez S. Making PCR a normal routine of the food microbiology lab. PCR Methods in Foods. 2006. pp. 51–68.

- Verma NK, Reeves PR. Identification and sequence of rfbS and rfbE, which determine antigenic specificity of group A and group D salmonellae. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5694–5701. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.10.5694-5701.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Smith NH, Nelson K, Crichton PB, Old DC, Whittam TS, Selander RK. Evolutionary origin and radiation of the avian-adapted non-motile salmonellae. J Med Microbiol. 1993;38:129–139. doi: 10.1099/00222615-38-2-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Leon S, Ramiro R, Arroyo M, Diez R, Usera MA, Echeita MA. Blind comparison of traditional serotyping with three multiplex PCRs for the identification of Salmonella serotypes. Res Microbiol. 2007;158:122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder I, Nietfeld JC, Galland J, Yearly T, Sargeant JM, Oberst R, Tamplin ML, Luchansky JB. Comparison of cultivation and PCR-hybridization for detection of Salmonella in porcine fecal and water samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:2477–2484. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.7.2477-2484.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y, Berrang M, Liu T, Hofacre C, Sanchez S, Wang L, Maurer JJ. Rapid detection of Campylobacter coli, C. jejuni and Salmonella enterica on poultry carcasses using PCR-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:3492–3499. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.6.3492-3499.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Liljebjelke K, Bartlett E, Hofacre C, Sanchez S, Maurer JJ. Application of nested polymerase chain reaction to detection of Salmonella in poultry environment. J Food Prot. 2002;65:1227–1232. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-65.8.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamperini K, Soni V, Waltman D, Sanchez S, Theriault EC, Bray J, Maurer JJ. Molecular characterization reveals Salmonella enterica serovar 4,[5],12:i:- from poultry is a variant Typhimurium serovar. Avian Dis. 2007;51:958–964. doi: 10.1637/7944-021507-REGR.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltran P, Plock SA, Smith NH, Whittam TS, Old DC, Selander RK. Reference collection of strains of the Salmonella typhimurium complex from natural populations. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:601–606. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-3-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd EF, Wang FS, Beltran P, Plock SA, Nelson K, Selander RK. Salmonella reference collection B (SARB): strains of 37 serovars of subspecies I. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:1125–1132. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-6-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson CR, Quist C, Lee MD, Keyes K, Dodson SV, Morales C, Sanchez S, White DG, Maurer JJ. Genetic relatedness of Salmonella isolates from nondomestic birds in Southeastern United States. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1860–1865. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.5.1860-1865.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swamy SC, Barnhart HM, Lee MD, Dreesen DW. Virulence determinants invA and spvC in salmonellae isolated from poultry products, wastewater, and human sources. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3768–3771. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.10.3768-3771.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljebjelke KA, Hofacre CL, Liu T, White DG, Ayers S, Young S, Maurer JJ. Vertical and horizontal transmission of Salmonella within integrated broiler production system. Foodborne Path Dis. 2005;2:90–102. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2005.2.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous . Difco Manual. 11. Sparks: Difco Laboratories, Division of Becton Dickinson and Co; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Brown PK, Romana LK, Reeves PR. Molecular analysis of the rfb gene cluster of Salmonella serovar Muenchen (strain M67): the genetic basis of the polymorphism between groups C2 and B. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1385–1394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang XM, Neal B, Santiago F, Lee SJ, Romana LK, Reeves PR. Structure and sequence of the rfb (O-antigen) gene cluster of Salmonella serovar typhimurium (Strain LT2) Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:695–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Romana LK, Reeves PR. Sequence and structural analysis of the rfb (O antigen) gene cluster from a group C1 Salmonella enterica strain. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:1843–1855. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-9-1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Verma NK, Romana LK, Reeves PR. Relationship among the rfb regions of Salmonella serovars A, B, and D. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4814–4819. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.15.4814-4819.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Romana LK, Reeves PR. Molecular analysis of a Salmonella enterica group E1 rfb gene cluster: O antigen and the genetic basis of the major polymorphism. Genetics. 1992;130:432–443. doi: 10.1093/genetics/130.3.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten BJ, Joys TM. Molecular analyses of the Salmonella g flagellar antigen complex. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5359–5365. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.17.5359-5365.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanegas RA, Joys TM. Molecular analyses of the phase-2 antigen complex 1, 2 of Salmonella spp. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3863–3864. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.13.3863-3864.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Aquilla RT, Bechtel LJ, Videler JA, Eron JJ, Gorczyca P, Kaplan JC. Maximizing sensitivity and specificity of PCR by pre-amplification heating. Nucl Acids Res. 1991;19:3749. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.13.3749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T, Eds . Molecular Cloning: a Laboratory Manual. 2. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Wittwer CT, Fillmore GC, Hillyard DR. Automated polymerase chain reaction capillary tubes with hot air. Nucl Acids Res. 1989;17:4353–4357. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.11.4353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton AC, Banks JG, Penn CW. Optimization of RAPD for fingerprinting Salmonella. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1997;24:243–248. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.1997.00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]