Abstract

Immune function is likely to be shaped by multiple infections over time. Infection with one pathogen can confer cross-protection against heterologous pathogens. We tested the hypothesis that latent murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (γHV68) infection modulates host inflammatory responses and susceptibility to mouse adenovirus type 1 (MAV-1). Mice were infected intranasally (i.n.) with γHV68. 21 days later, they were infected i.n. with MAV-1. We assessed cytokine and chemokine expression by quantitative reverse transcriptase real-time PCR, cellular inflammation by histology, and viral loads by quantitative real-time PCR. Previous γHV68 infection led to persistently upregulated IFN-γ in lungs and spleen and persistently upregulated CCL2 and CCL5 in the lungs. Previous γHV68 infection amplified MAV-1-induced CCL5 upregulation and cellular inflammation in the lungs. Previous γHV68 infection was associated with lower MAV-1 viral loads in the spleen but not the lung. There was no significant effect of previous γHV68 on IFN-γ expression or MAV-1 viral loads when the interval between infections was increased to 44 days. In summary, previous γHV68 infection modulated lung inflammatory responses and decreased susceptibility to a heterologous virus in an organ- and time-dependent manner.

Introduction

The herpesviruses are double-stranded DNA viruses that have the ability to establish lifelong latency in their host. Studies of the pathogenesis of the human gammaherpesviruses, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, are limited due to the species-specificity of the viruses. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (γHV68) provides a useful model to study the pathogenesis of a gammaherpesvirus in its natural host. Similar to its human counterparts, γHV68 establishes latency in B lymphocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells following an initial phase of lytic replication (Flano et al., 2000; Stewart et al., 1998). In some cases, lung epithelial cells may also harbor latent virus (Stewart et al., 1998). Viral latency is maintained by a complicated interplay between host and virus. A number of γHV68 gene products are involved in active modulation of host immune responses, including the γHV68 K3 protein, which downregulates MHC class I (Boname et al., 2004), and the γHV68 M3 protein, which sequesters host chemokine proteins (Parry et al., 2000; Van Berkel et al., 2000). While both K3 and M3 are lytic genes, they are also expressed during latent infection (Rochford et al., 2001) and so may also contribute to the maintenance of latency. γHV68 infection induces long-term changes in patterns of cytokine expression. We have reported persistent upregulation of lung CCL5 expression up to 29 days following intranasal (i.n.) γHV68 infection (Weinberg et al., 2002), and production of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interferon (IFN)-γ remains upregulated in the spleen up to at least 41 days post-infection (d.p.i.) (Barton et al., 2007). It is unclear whether these long-term alterations in cytokine production are the result of a “resetting” of baseline host cytokine production following acute γHV68 infection or if they are the result of ongoing stimulation triggered by intermittent reactivation of latent virus.

It is also unclear whether viral immunomodulatory functions or ongoing host immune responses to latent infection affect the pathogenesis of subsequent infections. The majority of individuals are infected with EBV during childhood (Rickinson and Kieff, 2001). Most are also infected with other herpesviruses, such as herpes simplex virus and cytomegalovirus, that establish persistent infections. While persistent viruses typically do not cause clinically significant disease in immunocompetent hosts, their presence may have unrecognized effects on the way in which their hosts respond to subsequent immunologic stimuli. In a recent report, Barton and colleagues demonstrated increased resistance to the intracellular pathogens Listeria monocytogenes and Yersinia pestis, but not to West Nile virus (WNV), in mice latently infected with γHV68 or with murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV, Barton et al., 2007). The protection afforded by latent γHV68 was linked to prolonged IFN-γ production and macrophage activation following i.n. γHV68 infection (Barton et al., 2007) and appeared to be a process distinct from previously described mechanisms of cross protection such as heterologous immunity (Selin et al., 2006) or nonspecific activation of CD8+ memory T cells (Berg et al., 2003).

Latent γHV68 infection is established following both i.n. and intraperitoneal (i.p.) infection (Tibbetts et al., 2003). Specific comparisons of long-term changes in cytokine production or other immune function in specific compartments (for example, lung and spleen) following different routes of inoculation have not been performed. It is possible, however, that these γHV68-induced immunologic changes differ depending on the route of infection. In the present study, we investigated whether γHV68 latency was associated with altered susceptibility to acute respiratory infection with an unrelated virus, mouse adenovirus type 1 (MAV-1). In addition, we sought to define effects on long-term alterations in lung and spleen cytokine and chemokine expression in the setting of latent γHV68 infection.

Results

Latent γHV68 infection is associated with upregulated lung and spleen IFN-γ expression

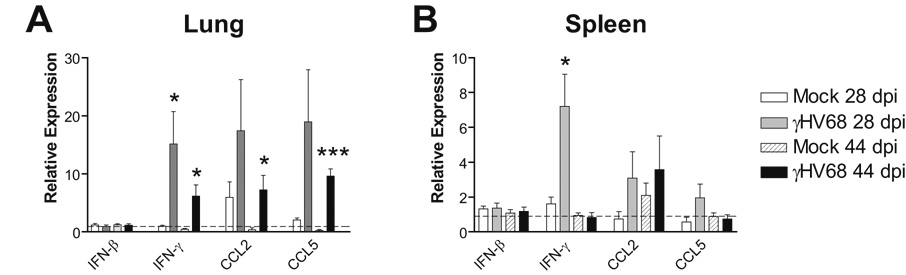

We and others have described pulmonary inflammation induced by acute γHV68 infection (Sarawar et al., 2002; Weinberg et al., 2004; Weinberg et al., 2002). The expression of a variety of cytokines and chemokines is upregulated in the lungs following i.n. inoculation with γHV68. Protection against bacterial challenge conferred by latent γHV68 infection is likely to be due at least in part to long-term changes in cytokine expression, in particular persistent IFN-γ upregulation, induced by latent γHV68, as measured in the serum (Barton et al., 2007). We used quantitative reverse transcriptase real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) to determine whether local lung and spleen expression of IFN-γ and other cytokines was persistently upregulated by latent γHV68 infection. Compared to γHV68-naïve mice, baseline IFN-γ expression prior to MAV-1 infection was significantly upregulated in the lungs of γHV68-infected mice at 28 days following infection (Fig. 1A, 0.99 ± 0.18 fold vs. 15.13 ± 5.59 fold higher than reference animals mock infected i.p.). IFN-γ expression remained upregulated in the lungs of γHV68-infected mice at 44 days following infection, although the magnitude of this effect was less than at 28 days following γHV68 infection (Fig. 1A, 0.45 ± 0.12 fold vs. 6.19 ± 1.92 fold higher than reference animals) following γHV68 infection. This effect was less pronounced in the spleens of γHV68-infected mice at 28 d.p.i. (Fig. 1B, 1.62 ± 0.38 fold vs. 7.22 ± 1.84 fold higher than reference animals) and was absent in spleens at 44 d.p.i. (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Long-term effects of γHV68 infection on cytokine and chemokine expression. Mice were mock infected or infected i.n. with 4 × 104 PFU γHV68. Expression of the indicated transcripts in lung (A) and spleen (B) was measured using qRT-PCR. Data were normalized to GAPDH expression and are presented as expression relative to a reference group (mice mock infected i.p.; dotted line on each graph). For experimental groups, data represent means ± SEM (n=5 animals per group; *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001 compared to γHV68-naïve mice at the same time point.

We assayed other cytokines and chemokines at these time points in order to determine whether persistent effects of γHV68 infection were specific to IFN-γ or were more generalized. CCL2 and CCL5 are chemokines that can be induced by IFN-γ (Casola et al., 2002; Martin and Dorf, 1991; Pype et al., 1999; Stellato et al., 1995) and that are upregulated in the lung during both γHV68 (Weinberg et al., 2002) and MAV-1 (Weinberg et al., 2005) respiratory infection. Both CCL2 and CCL5 remained upregulated in the lungs of γHV68-infected mice at 28 and 44 d.p.i. compared to γHV68-naïve mice (Fig. 1A). The effects of γHV68 infection on lung CCL2 and CCL5 expression were of a similar magnitude to the effect on IFN-γ expression and diminished to a similar degree between 28 and 44 d.p.i. Neither CCL2 nor CCL5 were upregulated in the spleens of γHV68-infected mice compared to γHV68-naïve mice at 28 or 44 d.p.i. (Fig. 1B). Lung and spleen expression of IFN-β were unaffected by γHV68 infection at these time points (Fig. 1A and 1B), as were lung and spleen expression of IL-4 and CXCL1 (data not shown).

Latent γHV68 infection modulates MAV-1-induced lung CCL5 expression

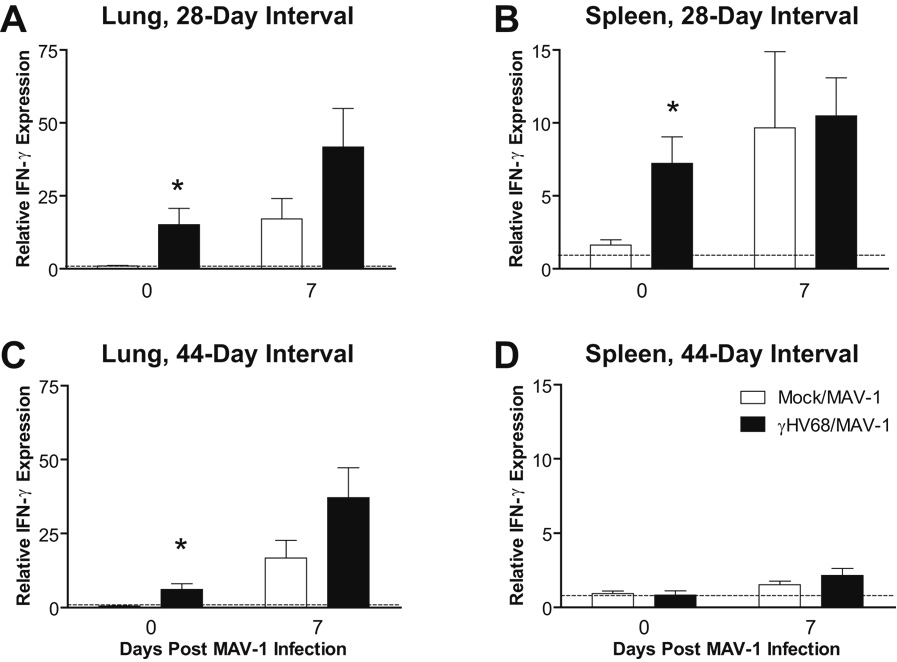

We have previously characterized acute MAV-1 respiratory infection (Weinberg et al., 2005). Following i.n. infection of mice with 105 plaque-forming units (PFU) MAV-1, peak viral gene expression and titers of infectious virus are detected at 7 d.p.i. Infectious virus is no longer detected in the lungs by plaque assay by 14 d.p.i., although MAV-1 DNA can be detected in the lung by nested PCR and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) up to at least 44 d.p.i. (unpublished data). Like γHV68, MAV-1 respiratory infection induces the upregulation of multiple chemokines and the influx of immune cells into the lung (Weinberg et al., 2005). To determine whether latent γHV68 infection modulates host responses to acute MAV-1 respiratory infection, we inoculated mice i.n. with MAV-1 after the establishment of γHV68 latency. When MAV-1 infection followed γHV68 infection by either 28 or 44 days, IFN-γ expression was further induced in the lung and spleen 7 days after MAV-1 infection (Figs. 2A–D), but there were no statistically significant differences between γHV68-naïve and γHV68-infected mice in the levels of MAV-1-induced IFN-γ expression.

FIG. 2.

Effects of γHV68 infection on MAV-1-induced lung and spleen IFN-γ expression. Mice were mock infected or infected i.n. with 4 × 104 PFU γHV68. All mice were then infected i.n. with 105 PFU MAV-1 after 28 days (A, B) or 44 days (C, D). Lung (A,C) and spleen (B,D) IFN-γ expression was measured using qRT-PCR. Data were normalized to GAPDH expression and are presented as expression relative to a reference group (mice mock infected i.p.), whose value is set to 1 in each case. For experimental groups, data represent means ± SEM (n=5 to 10 animals per group; * P<0.05 by Student’s t test compared to γHV68-naïve group at the same time point).

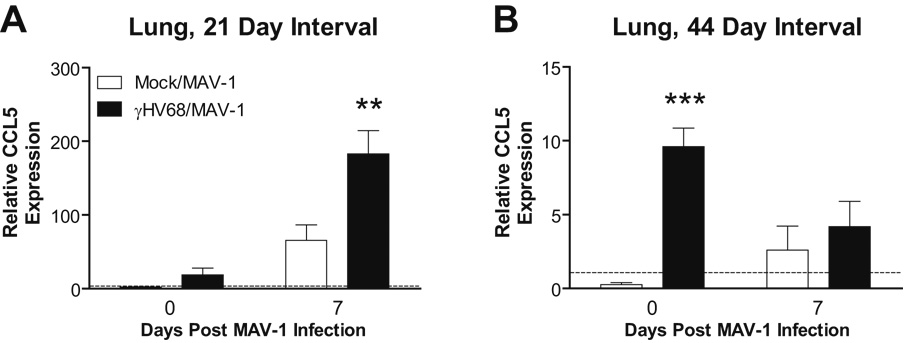

MAV-1 infection upregulated lung expression of CCL5 at 7 d.p.i. in γHV68-naïve mice compared to levels measured before MAV-1 infection. When MAV-1 infection followed γHV68 infection by 28 days, CCL5 upregulation at 7 days post-MAV-1 infection was significantly greater in the lungs of γHV68-infected mice compared to γHV68-naïve mice (Fig. 3A, compare open and dark bars at 7 days post MAV-1 infection). Increased time between γHV68 and MAV-1 infections was associated with dampening, rather than amplification, of lung CCL5 responses induced by MAV-1 (Fig. 3B). When mice were infected with MAV-1 44 days following γHV68 infection, levels of CCL5 expression decreased from their already elevated baseline in γHV68-infected mice at 7 days post-MAV-1 infection.

FIG. 3.

Effects of γHV68 infection on MAV-1-induced lung CCL5 expression. Mice were mock infected or infected i.n. with γHV68. All mice were then infected i.n. with MAV-1 after 28 days (A) or 44 days (B). Lung CCL5 expression was measured using qRT-PCR before MAV-1 infection and then at 7 days following MAV-1 infection. Data were normalized to GAPDH expression and are presented as expression relative to a reference group (mice mock infected i.p.), whose value is set to 1 in each case. Data represent means ± SEM (n=5 to 10 animals per group; ** P<0.01 and *** P<0.001 by Student’s t test compared to γHV68-naïve group at the same time point).

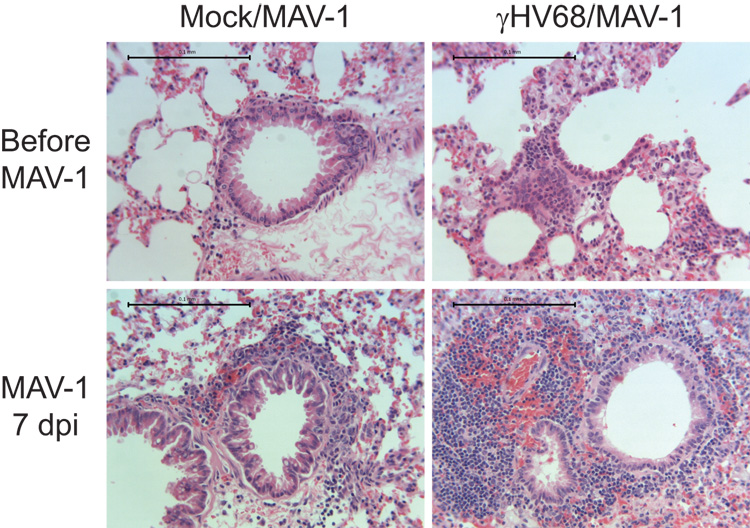

Latent γHV68 infection amplifies MAV-1-induced lung cellular inflammation

To determine whether cellular inflammatory responses corresponded with chemokine expression in the lung, we evaluated histological changes in hematoxylin and eosin-stained lung sections. Lungs from mock-infected mice showed little evidence of cellular inflammation. Lungs of mice infected i.n. with γHV68 had persistent mononuclear cellular infiltrates surrounding airways at 21 d.p.i. (Fig. 4). As we have previously described (Weinberg et al., 2005), acute MAV-1 respiratory infection in γHV68-naïve mice induced a patchy mononuclear cell infiltrate focused around medium and large airways. At 7 days post-MAV-1 infection, there was more cellular inflammation in the lungs of γHV68-infected mice compared to γHV68-naïve mice (Fig. 4). In these mice, dense, nodular collections of mononuclear cells were observed adjacent to many airways. Latent γHV68 therefore amplified cellular inflammation in the lungs of mice subsequently infected with MAV-1.

FIG. 4.

γHV68 amplifies MAV-1-induced lung cellular inflammation. Mice were mock infected or infected i.n. with γHV68. All mice were then infected i.n. with MAV-1 after 28 days. Lungs were harvested before MAV-1 infection and then at 7 d.p.i. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections were prepared from paraffin-embedded sections. Images are representative of at least 2 animals per condition. Scale bars, 100 µm.

MAV-1 viral loads are lower in spleens of γHV68-infected mice

Barton and colleagues reported that latent γHV68 infection established following i.n. inoculation confers protection against subsequent i.p. challenge with L. monocytogenes and either i.n. or subcutaneous challenge with Y. pestis, but not against footpad inoculation with WNV (Barton et al., 2007). To determine whether latent γHV68 decreased susceptibility to a respiratory viral infection, we challenged mice i.n. with MAV-1 28 days following i.n. γHV68 infection. We quantified MAV-1 viral loads in lungs using qPCR. Previous reports by other groups (Lenaerts et al., 2006; Lenaerts et al., 2005) use qPCR to quantify MAV-1 viral loads in a manner similar to that used on our study. In addition, a recent publication demonstrates good correlation between qPCR measurements of γHV68 viral loads and plaque assay data during acute respiratory infection (Ptaschinski and Rochford, 2008). Although plaque assays may reveal subtle differences in viral replication missed by qPCR, we relied on qPCR to provide sensitive and specific measurements of both MAV-1 and γHV68 DNA and to avoid the potential confusion of plaques being formed by two different viruses present in organs of coinfected animals.

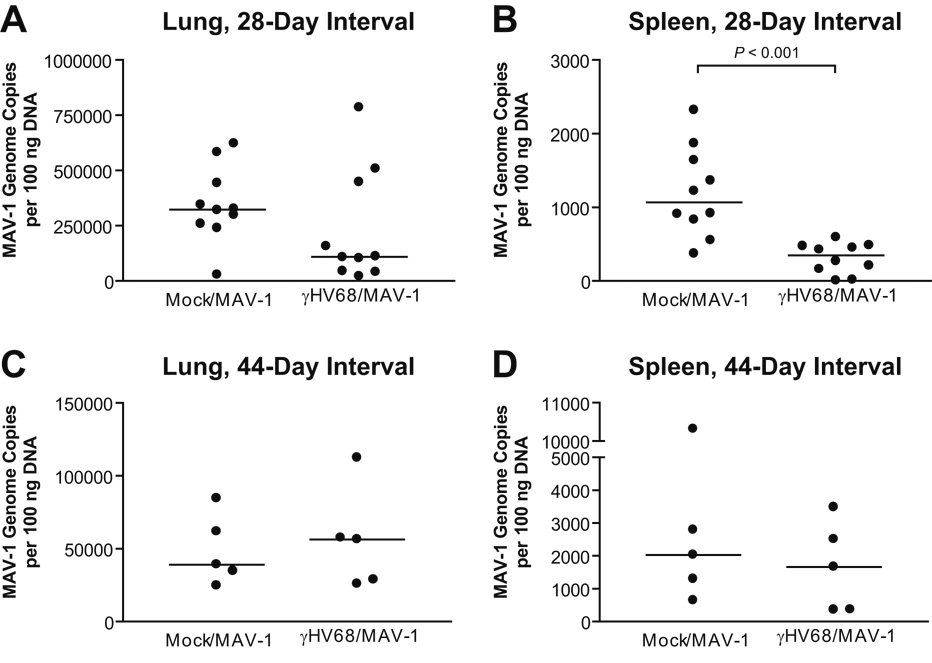

At 7 days post-MAV-1 infection, MAV-1 viral loads were not significantly different in the lungs of γHV68-infected mice compared to γHV68-naïve mice (Fig. 5A). The spleen is another target organ for MAV-1 following i.n. infection (Kajon et al., 1998). We quantified MAV-1 viral loads using qPCR to determine whether latent γHV68 affected levels of MAV-1 in the spleen. Overall, MAV-1 viral loads were lower in the spleen than in the lung at 7 d.p.i. (compare Y-axes in Figs. 5A and 5B). MAV-1 viral loads were significantly lower in the spleens of γHV68-infected mice compared to γHV68-naïve mice (Fig. 5B, 1198 ± 193 MAV-1 genome copies per 100 ng DNA in γHV68-naïve mice versus 308 ± 65 in γHV68-infected mice, mean ± SEM, P<0.001). By this measure in the spleen, the principal reservoir for latent γHV68, γHV68-infected mice were therefore less susceptible to subsequent infection with MAV-1. We observed a similar effect, with lower MAV-1 viral loads in the spleens of γHV68-infected mice compared to γHV68-naïve mice, when γHV68 was delivered i.p. rather than i.n. (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Effects of γHV68 on MAV-1 viral loads. Mice were mock infected or infected i.n. with γHV68. All mice were then infected i.n. with MAV-1 after 28 days (A, B) or 44 days (C, D). MAV-1 viral loads were measured by quantitative real-time PCR in the lungs (A, C) and spleens (B, D) of coinfected mice at 7 days following MAV-1 infection. Data are expressed as genome copies of MAV-1 per 100 ng input DNA. Symbols represent values for individual mice and horizontal bars represent medians for each group. P values calculated using the Mann-Whitney rank sum test compare MAV-1 viral loads in γHV68-infected mice to MAV-1 viral loads in γHV68-naive mice. Any P value not presented was > 0.05.

Latent γHV68 infection confers protection against subsequent bacterial infection when the bacterial infection occurs up to 3 months following i.n. γHV68 infection (Barton et al., 2007). To determine whether the effects of latent γHV68 infection on subsequent MAV-1 infection lasted beyond 28 days, we infected animals i.n. with MAV-1 44 days following γHV68 infection. After this interval between infections, there were no differences in MAV-1 viral loads at 7 d.p.i. between γHV68-infected and γHV68-naïve mice in the lungs (Fig. 5C) or spleen (Fig. 5D). To address the possibility that prior γHV68 infection influenced MAV-1 viral loads at times later than 7 days post MAV-1 infection, we conducted an additional experiment in which MAV-1 infection followed γHV68 infection by 38 days. There were no significant differences in MAV-1 lung and spleen viral loads between γHV68-infected and γHV68-naïve mice at 14 days following MAV-1 infection (Supplemental Figure).

Acute MAV-1 infection does not increase γHV68 viral loads

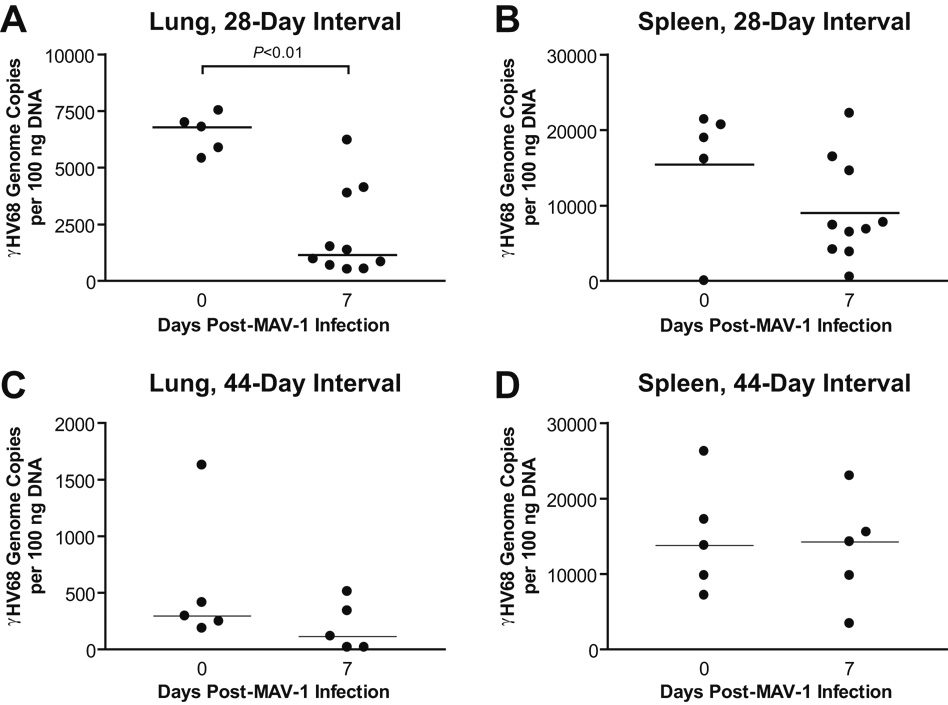

Reactivation from latency is a critical component of the gammaherpesvirus life cycle. While the molecular events that lead to gammaherpesvirus reactivation are increasingly understood, the physiological stimuli that trigger reactivation are not well described. Inflammatory challenges, including intra-abdominal bacterial infection (Cook et al., 2002) and administration of exogenous TNF-α (Koffron et al., 1999), have been reported to induce the reactivation of latent MCMV in vivo. To determine whether acute MAV-1 infection induced reactivation of latent γHV68, we quantified γHV68 viral loads in the lungs and spleens of latently infected mice that were subsequently infected with MAV-1. We detected γHV68 DNA in the lungs and spleens of γHV68-infected mice at 28 and 44 d.p.i. (Fig. 6). When MAV-1 infection followed γHV68 infection by 28 days, lung γHV68 viral loads decreased between 0 and 7 days post-MAV-1 infection (Fig. 6A) but spleen viral loads remained essentially unchanged (Fig. 6B). MAV-1 infection had no effect on lung or spleen γHV68 viral loads when γHV68 and MAV-1 infections were separated by 44 days (Figs. 6C and 6D). While it is likely that low-level γHV68 reactivation in these experiments escaped detection by the molecular assay we used, our data indicate that acute MAV-1 infection was not associated with increases in γHV68 DNA levels.

FIG. 6.

Acute MAV-1 infection does not alter γHV68 viral loads. Mice were mock infected or infected i.n. with γHV68. All mice were then infected i.n. with MAV-1 after 28 days (A, B) or 44 days (C, D). γHV68 viral loads were measured using quantitative real-time PCR in lungs (A, C) and spleens (B, D) before MAV-1 infection and then at 7 days following MAV-1 infection. Data are expressed as genome copies of γHV68 per 100 ng input DNA. Symbols represent values for individual mice and horizontal bars represent medians for each group. P values calculated using the Mann-Whitney rank sum test compare γHV68 viral loads before and after MAV-1 infection. Any P value not presented was > 0.05.

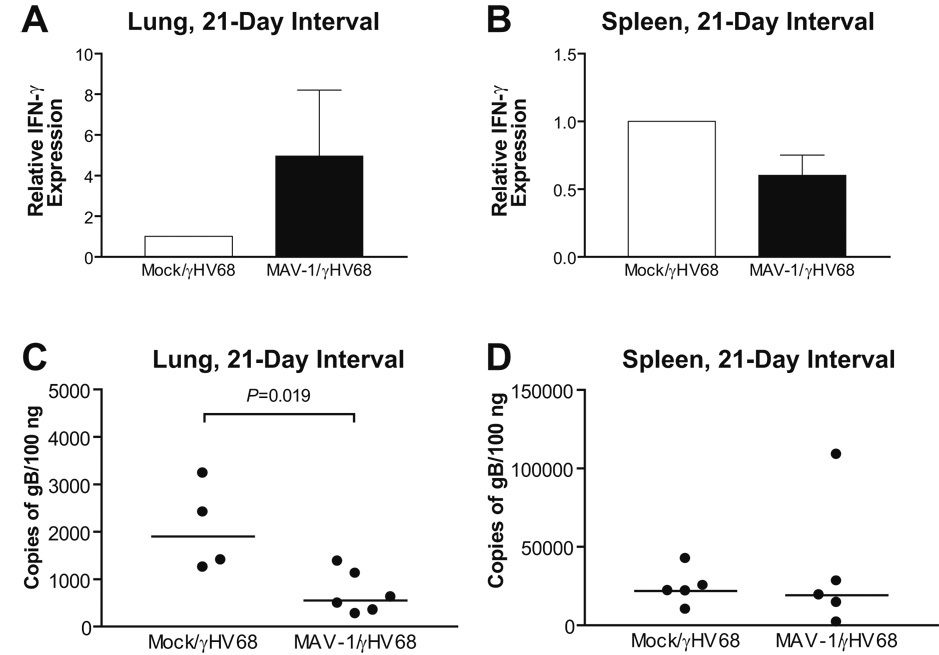

Prior MAV-1 infection modulates susceptibility to acute γHV68 infection

Latent infection with either γHV68 or MCMV was shown to confer cross protection to bacterial pathogens (Barton et al., 2007). Our results suggest that latent γHV68 conferred resistance to subsequent MAV-1 infection. To determine whether cross protection to γHV68 could be established following MAV-1 infection, we infected mice i.n. with MAV-1. 21 days later, MAV-1-naïve and MAV-1-infected mice were then infected i.n. with γHV68. We used qRT-PCR to measure lung and spleen IFN-γ expression and qPCR to measure lung and spleen γHV68 viral loads at 7 days post-γHV68 infection. Lung IFN-γ expression induced by γHV68 was increased in MAV-infected mice relative to MAV-1-naïve mice (Fig. 7A), while spleen IFN-γ expression induced by γHV68 was modestly decreased in MAV-infected mice relative to MAV-1-naïve mice (Fig. 7B). Increased lung IFN-γ expression correlated with significantly lower γHV68 viral loads in the lungs of MAV-1-infected mice (Fig. 7C, 2071 ± 464 γHV68 genome copies per 100 ng DNA in MAV-1-naïve mice versus 701 ± 182 in MAV-1-infected mice, mean ± SEM, P=0.019). In contrast, prior MAV-1 infection had no effect on spleen γHV68 viral loads (Fig. 7D). Prior MAV-1 infection was therefore capable of altering susceptibility to subsequent γHV68 infection in a manner that correlated with organ-specific changes in IFN-γ expression.

FIG. 7.

Effects of prior MAV-1 infection on acute γHV68 infection. Mice were mock infected or infected i.n. with MAV-1. All mice were then infected i.n. with γHV68 after 21 days. Lung (A) and spleen (B) IFN-γ expression was measured using qRT-PCR. Data was normalized to GAPDH expression and are presented as expression in MAV-1-infected mice relative to MAV-1-naïve mice, whose value is set to 1. γHV68 viral loads were measured by quantitative real-time PCR in the lungs (C) and spleens (D) of coinfected mice at 7 days following γHV68 infection. Data are expressed as genome copies of γHV68 per 100 ng input DNA. Symbols represent values for individual mice and horizontal bars represent medians for each group. P values calculated using the Mann-Whitney rank sum test compare γHV68 viral loads in MAV-1-infected mice to γHV68 viral loads in MAV-1-naïve mice. Any P value not presented was > 0.05.

Discussion

The immune system depends on a state of memory established following a primary infection to provide some measure of protection from subsequent infection with the same pathogen. Accumulating evidence suggests that cross-protection, in which a primary infection with one pathogen confers protection from subsequent infection with an unrelated pathogen, can occur in a variety of circumstances and via several different mechanisms. In this study, we report that prior γHV68 infection alters responses to subsequent MAV-1 respiratory infection. Mice previously infected with γHV68 had lower MAV-1 viral loads in the spleens than did γHV68-naïve mice. We demonstrate that this effect was organ-specific, present in spleen but not lung, despite upregulation of IFN-γ expression in both organs at the time of MAV-1 infection. Both IFN-γ upregulation and the effect of previous γHV68 infection on MAV-1 viral loads diminished with increased time between γHV68 and MAV-1 infections. The ability to provide cross protection was not limited to latent γHV68 infection, because we observed lower γHV68 viral loads in the lungs during acute γHV68 infection of mice persistently infected with MAV-1 compared to MAV-1-naïve mice.

Similar to previous work by Barton and colleagues (2007), we report persistent upregulation of IFN-γ expression associated with latent γHV68 infection. Like human adenoviruses, MAV-1 is relatively resistant to direct effects of IFN-γ in vitro (Kajon and Spindler, 2000). This is likely due to immunomodulatory effects of the MAV-1 E1A gene, because E1A-null MAV-1 mutant viruses are more sensitive to IFN-γ than wild type MAV-1 (Kajon and Spindler, 2000). IFN-γ likely plays a role in vivo, however, because mice deficient for IFN-γ show more extensive MAV-1 replication than wild type mice (K.R. Spindler, personal communication). We found that local expression of IFN-γ remained upregulated in the lungs and spleen at time points after acute γHV68 infection has typically resolved. γHV68-infected mice had lower spleen MAV-1 viral loads following acute MAV-1 respiratory infection than did γHV68-naïve mice. Despite increased levels of IFN-γ expression in the lungs of γHV68-infected mice, however, we observed no differences in lung MAV-1 viral loads. Latent γHV68 is more abundant in the spleen than in the lungs (Fig. 6), which may lead to differences in local IFN-γ production stimulated by latent virus. Organ-specific differences in the way macrophages or other cell types respond to upregulated IFN-γ, chemokines or other mediators stimulated by latent γHV68 may also account for the lack of an effect of latent γHV68 on MAV-1 viral loads in the lung.

We also assessed lung expression of CCL2 and CCL5, chemokines that likely contribute to the control of viral infection by recruiting cells such as monocytes, lymphocytes, NK cells and dendritic cells (Luster, 1998). CCL2 and CCL5 expression is increased in the lungs of infected mice during acute MAV-1 respiratory infection (Weinberg et al., 2005), suggesting that these chemokines or cells they recruit recruited play roles in the control of acute MAV-1 infection. Similar to our previous findings (Weinberg et al., 2002), persistent chemokine upregulation was present in the lungs at 28 and 44 days following i.n. γHV68 infection. CCL2 and CCL5 production can be induced by IFN-γ (Casola et al., 2002; Martin and Dorf, 1991; Pype et al., 1999; Stellato et al., 1995), potentially linking persistent IFN-γ upregulation in the lungs of γHV68-infected mice to persistent upregulation of these chemokines. Persistent inflammation following γHV68 infection did not seem to be a universal, nonspecific phenomenon. We did not observe persistent upregulation of a type I interferon (IFN-β), a classic Th2-type cytokine (IL-4), or an additional chemokine (CXCL1), further suggesting that much of the persistent inflammation associated with γHV68 infection is driven by IFN-γ.

When acute MAV-1 infection followed γHV68 by 28 days, enhanced immunopathology and greater CCL5 upregulation were present in the lungs of γHV68-infected mice compared to γHV68-naïve controls. Chronic stimulation by increased local levels of CCL2, CCL5, or other mediators not measured in our study may prime immune cells resident in the lung to respond more exuberantly to acute MAV-1 infection, leading to even more pronounced cellular infiltrates in the lungs of γHV68-infected mice following MAV-1 infection. Alternatively, CCL5 production by the increased number of recruited inflammatory cells may account for the increased levels of CCL5.

The cellular infiltrates induced by acute MAV-1 infection of γHV68-infected mice resemble the follicular-like accumulation of lymphocytes termed bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue, or BALT. BALT has been described in a number of situations, often in the context of chronic inflammation (Tschernig and Pabst, 2000). Histological findings similar to those we report here, including BALT, were described in association with a variety of viral coinfections, in which increased BALT was frequently seen in coinfected animals compared to naïve animals infected with a single virus (Chen et al., 2003). In some cases, such as acute vaccinia virus (VV) infection of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV)-, MCMV- or influenza-immune mice, increased pulmonary pathology in coinfected animals was associated with decreased titers of the second pathogen, while in other cases (acute LCMV or acute MCMV infection of influenza-immune mice) it was associated with increased viral titers. Different patterns of cytokine induction specific to different viruses may account for opposite effects on subsequent infection with an unrelated virus. Alternatively, Chen and colleagues suggested that increased numbers of macrophages and lymphocytes recruited by acute LCMV or MCMV infection in influenza-immune mice could serve as targets of infection for LCMV and MCMV, allowing for increased titers of these viruses in influenza-immune mice (Chen et al., 2003). A similar effect during acute MAV-1 infection of γHV68-infected mice could balance out any cross-protection afforded by latent γHV68 infection, resulting in the lack of apparent differences in lung viral loads that we report.

Previous viral infection has been shown to alter host responses to subsequent viral challenges. For instance, mice infected with LCMV that were then infected with VV demonstrated improved survival, augmented viral clearance and altered immunopathology compared to LCMV-naïve mice (Chen et al., 2001). This effect was associated with the accumulation of LCMV-specific IFN-γ-producing memory CD8+ T cells following VV challenge. Similar effects on VV pathogenesis by immunity to MCMV or influenza A virus were also associated with enhanced Th1-type cytokine responses induced by VV (Chen et al., 2003). Latent γHV68 infection conferred protection from subsequent infection by the bacterial pathogens, L. monocytogenes and Y. pestis, but not by a viral pathogen, WNV (Barton et al., 2007). In that report, γHV68-mediated cross-protection also involved increased IFN-γ production but occurred in a T cell-independent manner. Instead, the authors showed that peritoneal macrophages were activated and exhibited increased bactericidal activity in mice latently infected with γHV68. They suggested that these effects were the result of ongoing subclinical reactivation of latent γHV68 and chronic stimulation of IFN-γ.

The generation of cross-protective responses can depend on the timing between infections. For instance, increased susceptibility to bacterial infection (L. monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella typhimurium) was noted when bacterial infection occurred 2 days following LCMV infection (Navarini et al., 2006). When bacterial infection was delayed until 5 days following LCMV infection in this study, LCMV-immune mice cleared L. monocytogenes better than LCMV-naïve controls (Navarini et al., 2006). On the other hand, Barton and colleagues demonstrate that the effects of latent γHV68 on subsequent bacterial infection remain fairly consistent over at least 12 weeks, although the magnitude of the effect was somewhat less at later time points (Barton et al., 2007). We demonstrate that γHV68-mediated cross-protection from MAV-1 became less pronounced over a relatively short time period. γHV68-mediated effects were different when mice were challenged with MAV-1 at 28 days versus 44 days following γHV68 infection. Spleen MAV-1 viral loads were significantly lower in γHV68-infected mice when infected with MAV-1 at 28 days, but this effect was absent when MAV-1 infection occurred 44 days following γHV68 infection. This may in part relate to the disappearance of upregulated spleen IFN-γ expression in mice latently infected with γHV68 (Fig. 2D). The γHV68 inoculum dose that we used (4 × 104 PFU) was similar to the dose used by Barton and colleagues (104 PFU) in their study reporting increased levels of IFN-γ in the serum as long as 41 days following i.n. γHV68 infection (Barton et al., 2007). Mouse strain-specific differences in immune responses to γHV68 between the BALB/c mice used in our study and the C57BL/6 mice used by Barton and colleagues may account for some of the differences between the coinfection models. Compared to C57BL/6 mice, BALB/c mice exhibited greater levels of lung IFN-γ production and viral gene expression in the lungs during acute γHV68 infection (Weinberg et al., 2004). In that study, however, we did not assess cytokine production at time points beyond 15 d.p.i. that would correspond to predominantly latent γHV68 infection. Taken together, our data suggest that it is more likely a persistent perturbation in host immune function induced by γHV68 infection, rather than latent γHV68 infection per se, that leads to decreased MAV-1 viral loads in the spleens of γHV68-infected animals.

An individual’s accumulated history of infections is likely to shape immune responses to subsequent pathogens, with each infection producing both short- and long-term changes in immune function. In this report, we expand on the understanding of how γHV68 modulates host immune responses to and control of a second pathogen, MAV-1. Changes mediated by γHV68 may be beneficial if they result in accelerated clearance of a pathogen, such as with MAV-1 in the spleens of γHV68-infected mice. This protection may come at the cost of enhanced immunopathology, such as that seen in the lungs following MAV-1 infection of γHV68-infected mice. Alterations in innate and adaptive immunity due to genetic differences engineered in knockout mice modulate host susceptibility to various pathogens. An increasing number of genetic differences are being identified in humans that result in altered immune responses and susceptibility to pathogens. Our work and work with other coinfection models highlight the fact that a history of infections, latent virus or otherwise, must be considered in addition to host genetic factors regulating immune responses when considering how a particular host will respond to an infection.

Materials and Methods

Viruses, mice and infections

Wild type γHV68 (WUMS strain, ATCC VR-1465) was grown in owl monkey kidney cells and titers of viral stocks were determined by plaque assay on 3T3 cells as previously described (Weinberg et al., 2002). Wild type MAV-1, kindly provided by Kathy Spindler (University of Michigan), was grown and passaged in NIH 3T6 fibroblasts, and titers of viral stocks were determined by plaque assay on 3T6 cells as previously described (Cauthen et al., 2007).

Four- to six-week old male BALB/c mice were purchased from Harlan and maintained in microisolator cages. Under light anesthesia with ketamine and xylazine, mice were inoculated either i.p. with 4 × 104 PFU γHV68 diluted to a total of 100 µl in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or i.n. with 4 × 104 PFU γHV68 diluted to a total volume of 40 µl in sterile PBS. Control mice were inoculated i.p. or i.n. with conditioned media at an equivalent dilution in PBS. Following infection, mice were returned to their cages and allowed to recover. Either 28, 38 or 44 days following γHV68 infection, mice were infected i.n. with 105 PFU MAV-1 under light anesthesia with ketamine and xylazine. Some mice were euthanized immediately prior to MAV-1 infection and the remainder at 7 days post-MAV-1 infection. Organs were harvested, snap frozen and stored at −20°C until processed further. In some mice, the order of infection was reversed so that they were initially mock infected or infected i.n. with MAV-1 and then infected i.n. with γHV68 21 days later. Organs were then harvested at 7 days post-γHV68 infection. All animal work complied with all relevant federal and institutional policies.

Histology

In a subset of mice, lungs were harvested and fixed in 10% formalin. Prior to fixation, lungs were gently inflated with PBS via the trachea to maintain lung architecture. After fixation, organs were embedded in paraffin, and 5 µm sections were cut for histopathology. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin to evaluate cellular infiltrates. Processed sections were viewed through a Laborlux 12 microscope (Leitz). Digital images were obtained with an EC3 digital imaging system (Leica Microsystems) using Leica Acquisition Suite software (Leica Microsystems). Scale bars were added to images using Leica Acquisition Suite software. Color balance was adjusted and images were assembled in Adobe Illustrator CS2 (Adobe Systems); otherwise, no image manipulation was used.

Isolation of RNA and DNA from organs

The left lung was homogenized with sterile glass beads and 1 ml TRIzol Reagent (Gibco-BRL) using a Mini Beadbeater (Biospec Products). The homogenates were incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes, and then 200 µl of chloroform were added to each sample. Following a 3-minute incubation at room temperature, the tubes were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The aqueous phase was transferred to a new microcentrifuge tube, and total RNA was precipitated with isopropanol. DNA was extracted from lung and spleen using the DNeasy® Tissue Kit (Quiagen Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Measurement of viral load

γHV68 and MAV-1 viral loads were measured in organs using qPCR. γHV68 and MAV-1 viral loads were determined in separate reactions using primers and probe to detect a 70 bp region of the γHV68 gB gene or a 59 bp region of the MAV-1 E1A gene (Table 1). 5 µl of extracted DNA were added to reactions containing TaqMan Universal PCR Mix (Applied Biosystems), forward and reverse primers (each at 300 nM final concentration for γHV68 gB, 200 nM final concentration for MAV-1 E1A) and probe (200 nM final concentration for γHV68 gB and MAV-1 E1A) in a 25 µl total reaction volume. qPCR analysis on an ABI Prism 7300 machine (Applied Biosystems) consisted of 40 cycles of 15 seconds at 90°C and 60 seconds at 60°C. Standard curves generated using known amounts of plasmid containing the γHV68 gB gene of the MAV-1 E1A gene were used to convert cycle threshold values for experimental samples to copy numbers of γHV68 gB DNA or MAV-1 E1A DNA, respectively. Copy numbers were standardized to the amount of input DNA and were expressed as copies of viral genome per 100 ng DNA. Triplicate measurements for each virus were made for each sample.

Table 1.

Primers and probes used for real-time PCR analysis.

| Target | Oligonucleotide | Sequence (5’ to 3’) |

|---|---|---|

| MAV-1 E1A | Forward Primer | GCACTCCATGGCAGGATTCT |

| Reverse Primer | GGTCGAAGCAGACGGTTCTTC | |

| Probe | TACTGCCACTTCTGC | |

| γHV68 gB | Forward Primer | GGCCCAAATTCAATTTGCCT |

| Reverse Primer | CCCTGGACAACTCCTCAAGC | |

| Probe | ACAAGCTGACCACCAGCGTCAACAAC | |

| IFN-γ | Forward Primer | AAAGAGATAATCTGGCTCTGC |

| Reverse Primer | GCTCTGAGACAATGAACGCT | |

| IFN-β | Forward Primer | AGCTCCAAGAAAGGACGAACAT |

| Reverse Primer | GCCCTGTAGGTGAGGTTGATCT | |

| GAPDH | Forward Primer | TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAG |

| Reverse Primer | GGATGCAGGGATGATGTTC |

Analysis of cytokine and chemokine gene expression

Cytokine gene expression was quantified in RNA extracted from organs using qRT-PCR. 2.5 µg of RNA was reverse transcribed using MMLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The resultant cDNA was amplified using gene expression assays for murine CCL2, CCL5, CXCL1, IL-4 and GAPDH (Applied Biosystems). 2 µl of cDNA were added to reactions containing TaqMan Universal PCR Mix and 1.25 µl each of 20x gene expression assay mix for a target cytokine and GAPDH in a 25 µl total reaction volume. The murine IFN-γ gene expression assay from Applied Biosystems did not reliably detect IFN-γ expression in BALB/c mice, although it did detect expression in C57BL/6 mice (data not shown). To detect murine IFN-γ in BALB/c mice, we used primers shown in Table 1. 2 µl of cDNA were added to reactions containing TaqMan Power SYBR Green PCR Mix and forward and reverse primers (each primer at 200 nM final concentration) in a 25 µl total reaction volume. A separate reaction was prepared with GAPDH primers (Table 1, each primer at 200 nM final concentration) for each sample. Murine IFN-β was detected in an identical manner using the primers shown in Table 1. qRT-PCR analysis consisted of 40 cycles of 15 seconds at 90°C and 60 seconds at 60°C. Melt curve analyses were performed for reactions using SYBR green. Quantification of target gene expression was normalized to GAPDH and expressed as fold change from control groups using the comparative CT method (Fink et al., 1998).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed for statistical significance using Microsoft Excel or Prism 3 for Macintosh (GraphPad Software Incorporated). For chemokine and cytokine expression data, differences between groups were analyzed using Student’s t test. For viral load data, differences between groups were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Greg Stempfle and Amy Lake for expert technical assistance and Kathy Spindler, Mike Imperiale and Beth Moore for helpful comments on the manuscript. JBW was supported by a University of Michigan Janette Ferrantino Young Investigator Award, a Child Health Research Center Junior Investigator Award (NIH K12 HD28820), NIH R21 HL080282 and NIH K08 HL083103. In addition, this research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through the University of Michigan’s Cancer Center Support Grant (NIH P30 CA46592).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barton ES, White DW, Cathelyn JS, Brett-McClellan KA, Engle M, Diamond MS, Miller VL, Virgin HWt. Herpesvirus latency confers symbiotic protection from bacterial infection. Nature. 2007;447(7142):326–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg RE, Crossley E, Murray S, Forman J. Memory CD8+ T cells provide innate immune protection against Listeria monocytogenes in the absence of cognate antigen. J Exp Med. 2003;198(10):1583–1593. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boname JM, Coleman HM, May JS, Stevenson PG. Protection against wild-type murine gammaherpesvirus-68 latency by a latency-deficient mutant. J. Gen. Virol. 2004;85(Pt 1):131–135. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19592-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casola A, Henderson A, Liu T, Garofalo RP, Brasier AR. Regulation of RANTES promoter activation in alveolar epithelial cells after cytokine stimulation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283(6):L1280–L1290. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00162.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauthen AN, Welton AR, Spindler KR. Construction of mouse adenovirus type 1 mutants. Methods Mol Med. 2007;130:41–59. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-166-5:41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HD, Fraire AE, Joris I, Brehm MA, Welsh RM, Selin LK. Memory CD8+ T cells in heterologous antiviral immunity and immunopathology in the lung. Nat Immunol. 2001;2(11):1067–1076. doi: 10.1038/ni727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HD, Fraire AE, Joris I, Welsh RM, Selin LK. Specific history of heterologous virus infections determines anti-viral immunity and immunopathology in the lung. Am. J. Pathol. 2003;163(4):1341–1355. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63493-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook CH, Zhang Y, McGuinness BJ, Lahm MC, Sedmak DD, Ferguson RM. Intra-abdominal bacterial infection reactivates latent pulmonary cytomegalovirus in immunocompetent mice. J. Infect. Dis. 2002;185(10):1395–1400. doi: 10.1086/340508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink L, Seeger W, Ermert L, Hanze J, Stahl U, Grimminger F, Kummer W, Bohle RM. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR after laser-assisted cell picking. Nat Med. 1998;4(11):1329–1333. doi: 10.1038/3327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flano E, Husain SM, Sample JT, Woodland DL, Blackman MA. Latent murine gamma-herpesvirus infection is established in activated B cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages. J. Immunol. 2000;165(2):1074–1081. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajon AE, Brown CC, Spindler KR. Distribution of mouse adenovirus type 1 in intraperitoneally and intranasally infected adult outbred mice. J. Virol. 1998;72(2):1219–1223. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1219-1223.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajon AE, Spindler KR. Mouse adenovirus type 1 replication in vitro is resistant to interferon. Virology. 2000;274(1):213–219. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffron A, Varghese T, Hummel M, Yan S, Kaufman D, Fryer J, Leventhal J, Stuart F, Abecassis M. Immunosuppression is not required for reactivation of latent murine cytomegalovirus. Transplant. Proc. 1999;31(1–2):1395–1396. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)02041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenaerts L, Daelemans D, Geukens N, De Clercq E, Naesens L. Mouse adenovirus type 1 attachment is not mediated by the coxsackie-adenovirus receptor. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(16):3937–3942. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenaerts L, Verbeken E, De Clercq E, Naesens L. Mouse adenovirus type 1 infection in SCID mice: an experimental model for antiviral therapy of systemic adenovirus infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005;49(11):4689–4699. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.11.4689-4699.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luster AD. Chemokines-chemotactic cytokines that mediate inflammation. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;338(7):436–445. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802123380706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CA, Dorf ME. Differential regulation of interleukin-6, macrophage inflammatory protein-1, and JE/MCP-1 cytokine expression in macrophage cell lines. Cell Immunol. 1991;135(1):245–258. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(91)90269-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarini AA, Recher M, Lang KS, Georgiev P, Meury S, Bergthaler A, Flatz L, Bille J, Landmann R, Odermatt B, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. Increased susceptibility to bacterial superinfection as a consequence of innate antiviral responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103(42):15535–15539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607325103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry CM, Simas JP, Smith VP, Stewart CA, Minson AC, Efstathiou S, Alcami A. A broad spectrum secreted chemokine binding protein encoded by a herpesvirus. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191(3):573–578. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptaschinski C, Rochford R. Infection of neonates with murine gammaherpesvirus 68 results in enhanced viral persistence in lungs and absence of infectious mononucleosis syndrome. J Gen Virol. 2008;89(Pt 5):1114–1121. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83470-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pype JL, Dupont LJ, Menten P, Van Coillie E, Opdenakker G, Van Damme J, Chung KF, Demedts MG, Verleden GM. Expression of monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1, MCP-2, and MCP-3 by human airway smooth-muscle cells. Modulation by corticosteroids and T-helper 2 cytokines. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;21(4):528–536. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.21.4.3660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickinson AB, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology. 4th ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. pp. 2575–2627. 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Rochford R, Lutzke ML, Alfinito RS, Clavo A, Cardin RD. Kinetics of murine gammaherpesvirus 68 gene expression following infection of murine cells in culture and in mice. J. Virol. 2001;75(11):4955–4963. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.11.4955-4963.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarawar SR, Lee BJ, Anderson M, Teng YC, Zuberi R, Von Gesjen S. Chemokine induction and leukocyte trafficking to the lungs during murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (MHV-68) infection. Virology. 2002;293(1):54–62. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selin LK, Brehm MA, Naumov YN, Cornberg M, Kim SK, Clute SC, Welsh RM. Memory of mice and men: CD8+ T-cell cross-reactivity and heterologous immunity. Immunol Rev. 2006;211:164–181. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00394.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellato C, Beck LA, Gorgone GA, Proud D, Schall TJ, Ono SJ, Lichtenstein LM, Schleimer RP. Expression of the chemokine RANTES by a human bronchial epithelial cell line. Modulation by cytokines and glucocorticoids. J Immunol. 1995;155(1):410–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JP, Usherwood EJ, Ross A, Dyson H, Nash T. Lung epithelial cells are a major site of murine gammaherpesvirus persistence. J. Exp. Med. 1998;187(12):1941–1951. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.12.1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibbetts SA, Loh J, Van Berkel V, McClellan JS, Jacoby MA, Kapadia SB, Speck SH, Virgin HW. Establishment and maintenance of gammaherpesvirus latency are independent of infective dose and route of infection. J. Virol. 2003;77(13):7696–7701. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.13.7696-7701.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschernig T, Pabst R. Bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT) is not present in the normal adult lung but in different diseases. Pathobiology. 2000;68(1):1–8. doi: 10.1159/000028109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Berkel V, Barrett J, Tiffany HL, Fremont DH, Murphy PM, McFadden G, Speck SH, Virgin HW. Identification of a gammaherpesvirus selective chemokine binding protein that inhibits chemokine action. J. Virol. 2000;74(15):6741–6747. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.15.6741-6747.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg JB, Lutzke ML, Alfinito R, Rochford R. Mouse strain differences in the chemokine response to acute lung infection with a murine gammaherpesvirus. Viral Immunol. 2004;17(1):69–77. doi: 10.1089/088282404322875467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg JB, Lutzke ML, Efstathiou S, Kunkel S, Rochford R. Elevated chemokine responses are maintained in lungs after clearance of viral infection. J. Virol. 2002;76(20):10518–10523. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.20.10518-10523.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg JB, Stempfle GS, Wilkinson JE, Younger JG, Spindler KR. Acute respiratory infection with mouse adenovirus type 1. Virology. 2005;340(2):245–254. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.