Abstract

DNA repair, checkpoint pathways and protection mechanisms against different types of perturbations are critical factors for the prevention of genomic instability. The aim of the present work was to analyze the roles of RAD17 and HDF1 gene products during the late stationary phase, in haploid and diploid yeast cells upon gamma irradiation. The checkpoint protein, Rad17, is a component of a PCNA-like complex—the Rad17/Mec3/Ddc1 clamp—acting as a damage sensor; this protein is also involved in double-strand break (DBS) repair in cycling cells. The HDF1 gene product is a key component of the non-homologous end-joining pathway (NHEJ). Diploid and haploid rad17Δ/rad17Δ, and hdf1Δ Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutant strains and corresponding isogenic wild types were used in the present study. Yeast cells were grown in standard liquid nutrient medium, and maintained at 30°C for 21 days in the stationary phase, without added nutrients. Cell samples were irradiated with 60Co γ rays at 5 Gy/s, 50 Gy ≤ Dabs ≤ 200 Gy. Thereafter, cells were incubated in PBS (liquid holding: LH, 0 ≤ t ≤ 24 h). DNA chromosomal analysis (by pulsed-field electrophoresis), and surviving fractions were determined as a function of absorbed doses, either immediately after irradiation or after LH. Our results demonstrated that the proteins Rad17, as well as Hdf1, play essential roles in DBS repair and survival after gamma irradiation in the late stationary phase and upon nutrient stress (LH after irradiation). In haploid cells, the main pathway is NHEJ. In the diploid state, the induction of LH recovery requires the function of Rad17. Results are compatible with the action of a network of DBS repair pathways expressed upon different ploidies, and different magnitudes of DNA damage.

Keywords: DNA double-strand break repair, γ rays, Stationary phase, Yeast

Introduction

The transmission of genetic information by duplication, transcription and translation is essential for the continuity of life. DNA repair, checkpoint pathways and protection mechanisms against different types of perturbations are critical factors, selected by evolution, for the prevention of genomic instability. Analysis of low eukaryotes such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae has provided understanding of the signal transduction cascades resulting in cell cycle arrest in response to DNA damage [1–3]. The interconnection of sensors of damage and effectors of DNA repair in cycling and non-cycling cells, either upon exposure to genotoxic agents or in normal metabolic conditions is currently under investigation. Checkpoints are signaling pathways that monitor the genome integrity and ensure the correct succession of cell cycle events. These checkpoints are triggered by several forms of DNA damage and various factors that block replication. An example of a damage-recognition protein is represented by S. cerevisiae Rad17 and its various homologues, i.e. Rad1 in humans. These proteins are components of a PCNA-like complex—the Rad17/Mec3/Ddc1 clamp—that is loaded by RFCs-Rad24 [3–5]. Recently, we demonstrated that this protein is also involved in double-strand break (DBS) repair. In eukaryotic cells, it is known that DBSs can be repaired at least by two pathways: homologous recombination and non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ). In the NHEJ pathway, two polypeptide subunits of 70 and 80 kDa (termed Ku in human cells, and Hdf in S. cerevisiae) bind to free double-stranded DNA ends and, in combination with Rad50 and Lig IV, secure the end joining. In humans, this pathway also involves a DNA-protein kinase (DNA PK), and acts in VDJ-specific recombination in the immune system [6, 7].

The aim of the present work was to analyze the roles of Rad17 and Hdf1 in genome stability during the late stationary phase, in haploid and diploid cells, upon gamma irradiation and nutrient stress. The stationary phase is the stage of growth kinetics during which no apparent change in cell number is observed. Hence, most cells maintain viability without added nutrients and contain an unreplicated set of DNA, just like in the G1 phase [8]. A comparison between the present observations regarding Rad17 and Hdf1 functions in stationary phase and these corresponding to the exponential phase of growth obtained previously [9] may provide some clues to the regulatory networks involved.

Materials and Methods

Yeast Strains and Culture Conditions

Diploid S. cerevisiae mutant strain rad17Δ/rad17Δ (WS9156), the corresponding isogenic wild type WS9154 [4, 9], and haploid strains SX46A and corresponding isogenic SX46Ahdf1Δ [7, 10] were used in the present study. The WS9154 diploid strain was constructed by mating the haploid SX46A (mating type a) and the haploid WS8105-C (of opposite mating type). WS9154 is isogenic to the previously described WS9131 [7], except for a TRP + marker (Wolfram Siede, personal communication). These strains were kindly provided by Prof. W. Siede.

Yeast cells were grown in liquid nutrient medium YPD [1% yeast extract (USB, Cleveland, OH), 2% bactopeptone (USB), and 2% glucose (Sigma, St. Louis, MO)], and maintained at 30°C for 21 days in the stationary phase [8], with aeration by shaking, without added nutrients.

Treatments were performed using stationary phase samples (N, 5–7 × 107 cells per ml). Solid nutrient medium was YPDA (YPD + 2% Agar, USB).

Treatments

Cell samples were washed two times with deionized water, resuspended in PBS at 4°C and irradiated with 60Co gamma rays (220 Excell Nordion) at 5 Gy/s, 50 Gy ≤ Dabs ≤ 200 Gy (IR). Thereafter, cells were incubated in PBS at 30°C (liquid holding: LH, 0 ≤ t ≤ 24 h). Either immediately after irradiation (IR) or after different times after incubation in PBS, aliquots of the cell suspensions and respective unirradiated controls were removed for DNA chromosomal analysis and for surviving fraction determinations in YPDA [9, 13].

Chromosomal DNA Analysis

Cell samples were washed twice and resuspended in 0.5 M phosphate buffer (pH 7) to a concentration of 5 × 108 cells/ml. DNA was isolated in low-melting agarose plugs upon enzymatic treatment (lyticase, proteinase K; Sigma, St Louis, MO). Chromosome separation was carried out by transverse alternating field electrophoresis (TAFE; Gene Line II, Beckman, Fullerton, CA). Analysis of chromosomal DNA bands was performed by laser densitometry of the gel photograph negatives (Software: Gel Scan XL Pharmacia) [9, 12, 13]. Each photograph shows the chromosomal bands corresponding to each cell sample (5 × 108 cells/ml). In the case of DNA double-strand break induction, a decrease in corresponding band intensity and a concomitant increase in interspersed fluorescence between bands are observed. Quantification is possible after laser absorbance analysis [14]. Estimation of mean values of induced DNA double-strand breaks (DBSs) and of corresponding standard deviations were based on the Poisson distribution as: − L Ix/Io, where Ix corresponds to the integral (surface) of a given chromosomal band in the densitograms after treatment and Io is the integral of the same chromosomal band in the respective control sample [9, 13–16].

Results

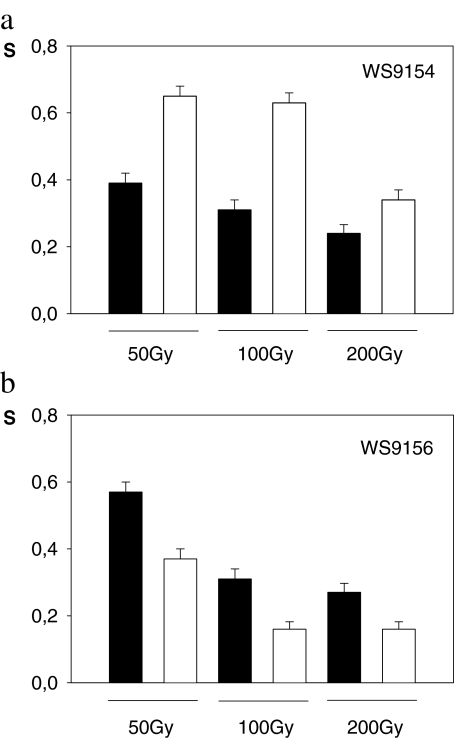

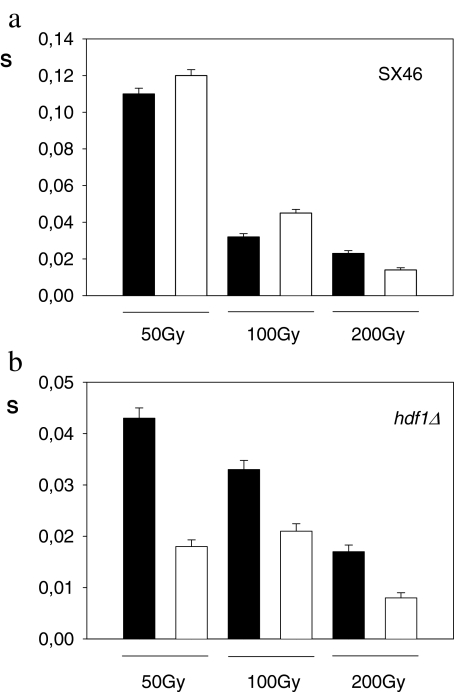

In the late stationary phase, upon nutrient and oxidative stress (nutrient depletion, IR exposure + LH), the wild type diploid strain WS9154 exposed to 50–200 Gy showed a decrease in survival fraction as a function of absorbed dose and an increase in survival after liquid holding (24 h in PBS, at 30°C; Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Bar diagrams showing the relative frequency of survival for different absorbed doses. Samples were plated in nutrient medium either immediately after irradiation (black bars: t = 0 h) or after 24 h incubation in buffer (white bars: t = 24 h). a: WS9154 wild type; b: rad17/rad17 mutant strain. Error bars correspond to binomial confidence intervals (p ≤ 0.05)

The rad17Δ/rad17Δ isogenic mutant strain exhibited similar radiosensitivity as the corresponding wild type strain, as measured by survival. However, in this case, no LH recovery was observed in the analyzed dose range (compare Fig. 1a and b).

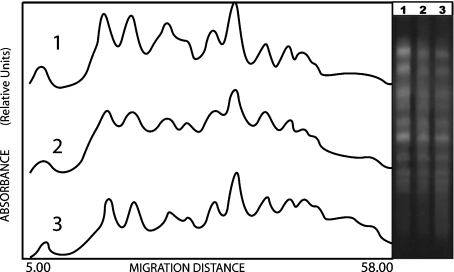

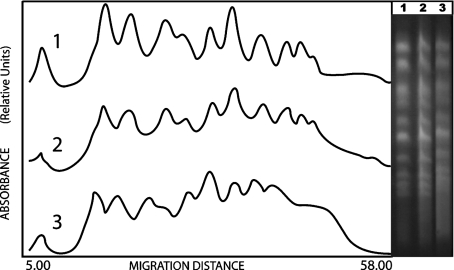

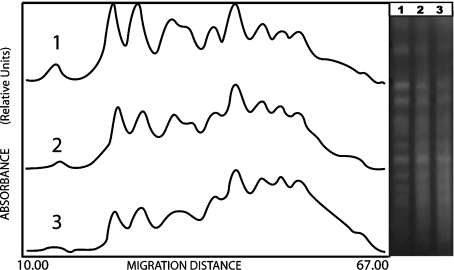

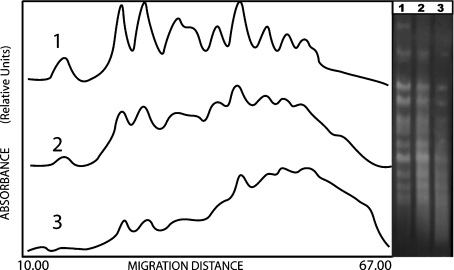

In correspondence to observations regarding survival, the WS9154 wild type strain showed a significant decrease of DSBs during LH (Fig. 2). Furthermore, in the same conditions, rad17Δ/rad17Δ mutant strain exhibited a significant increase of DSBs during LH (thus, a DNA degradation; see “smear” between chromosomal bands, Fig. 3). DBS mean values determinations after 100 Gy, and corresponding standard deviations, are given in Table 1 (see Section 2).

Fig. 2.

Left panel laser densitograms corresponding to diploid WS9154 strain. (1) control sample t = 0 h; (2) irradiated sample, D = 100 Gy, t = 0 h; (3) irradiated sample, D = 100 Gy, t = 24 h. The right panel shows the corresponding gel photograph after electrophoretic chromosomal separation. An increase of DNA fluorescence between bands indicates DNA fragmentation (see Section 2)

Fig. 3.

Left panel laser densitograms corresponding to the rad17/rad17 diploid mutant strain. (1) control sample t = 0 h; (2) irradiated sample, D = 100 Gy, t = 0 h; (3) irradiated sample, D = 100 Gy, t = 24 h. The right panel shows the corresponding gel photograph after electrophoretic separation. An increase of DNA fluorescence between bands indicates a higher DNA fragmentation than that observed in wild type (Fig. 2)

Table 1.

DSBs per genome ± standard deviation as determined by Poisson distribution, D = 100 Gy

| Strain | DSB (t = 0) | DSB (t = 24 h) |

|---|---|---|

| WS 9154 | 7.0 ± 2.6 | 1.1 ± 1.0 |

| WS 9156 | 7.0 ± 2.6 | 12.0 ± 3.4 |

| SX46 | 5.0 ± 2.2 | 2.0 ± 1.5 |

| Hdf1 | 6.0 ± 2.4 | 13.0 ± 3.6 |

In case of the SX46A haploid wild type strain and the isogenic SX46Ahdf1Δ mutant strain, surviving fractions as a function of absorbed doses are given in Fig. 4. Clearly, a low increase in survival during LH after 50–100 Gy is observed in the wild type strain (Fig. 4a). In the same conditions, the SX46A hdf1Δ mutant strain showed no LH survival or recovery. (Fig. 4b). Indeed, a significant survival decrease was observed after irradiation and LH in this mutant strain. Note that the hdf1Δ mutant strain is significantly more sensitive than the corresponding wild type for relatively low doses.

Fig. 4.

Bar diagrams showing the relative frequency of survival for different absorbed doses. Samples were plated in nutrient medium either immediately after irradiation (black bars: t = 0 h) or after 24 h incubation in buffer (white bars: t = 24 h). a: SX46 haploid wild type; b: SX46 hdf1Δ mutant strain. Error bars correspond to binomial confidence intervals (p ≤ 0.05)

In correspondence to observations regarding surviving fractions, pulsed-field electrophoresis of DNA indicated low DBS decreases after 50–100 Gy + LH in the SX46A haploid wild type strain (Fig. 5, Table 1). On the other hand, in case of the isogenic hdf1Δ mutant strain, a high DNA degradation—thus, a significant increase in DSBs—was observed (Fig. 6, Table 1).

Fig. 5.

Left panel laser densitograms corresponding to the haploid SX46 wild type strain. (1) control sample t = 0 h; (2) irradiated sample, D = 100 Gy, t = 0 h; (3) irradiated sample, D = 100 Gy, t = 24 h. The right panel shows the corresponding gel photograph after electrophoretic separation. An increase of DNA fluorescence between bands indicates DNA fragmentation

Fig. 6.

Left panel laser densitograms corresponding to SX46 hdf1Δ haploid mutant strain. (1) control sample t = 0 h; (2) irradiated sample, D = 100 Gy, t = 0 h; (3) irradiated sample, D = 100 Gy, t = 24 h. The right panel shows the corresponding gel photograph after electrophoretic separation. An increase of DNA fluorescence between bands indicates a higher DNA fragmentation than that observed in wild type (Fig. 5)

Discussion

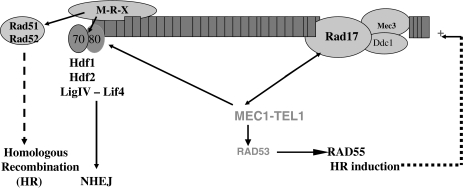

It is known that there are, at least, two main DNA DBS sensors in yeast and other eukaryotic cells: the Rad17-Mec3-Ddc1 complex and the Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 (MRX) complex. Both sensors have orthologous protein-complexes in other eukaryotes, including man [3, 17–19]. MRX sensor functions both in NHEJ and homologous recombination [20–22]. Mec1/hATM, a PI3 kinase, is at the core of a transduction cascade interacting at DBS-induced sites with sensors as well as with downstream effectors, enabling the amplification of the DNA damage response [3, 23] (see Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Rad17 and Hdf1 play essential roles in maintaining genome stability and chromosomal recovery in late stationary phase cells after exposure to gamma rays. Damage sensors are MRX (top, left) and Rad17-complex (top, right). In the haploid state the most probable DSBs repair pathway is NHEJ (MRX-Hdf1-Hdf2-LigIV-Lif4). In the diploid state, homologous recombination pathways depend on RAD17-MEC1-RAD53-RAD55-RAD51 gene products, as well as on MRX-Rad52 securing LH survival, and DSB repair [7, 10, 19]. Mec1/hATR and Tel1/hATM kinases are at the core of the network and interact with sensors at DNA damage and with downstream effectors, enabling the signal amplification [3, 17, 18, 21, 22]. (LigIV ligase IV, Lif4 LigIV co-factor)

Our results demonstrated that the proteins Rad17, as well as Hdf1, a key component of NHEJ, play essential roles in DBS repair and survival after irradiation, in diploid and haploid yeast, respectively, in late stationary phase, and upon nutrient stress (LH after irradiation; Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6).

Regarding the Rad17 protein, its function in DBS repair and survival, during liquid holding after radiation damage, was clearly evidenced by comparing responses of the diploid wild type strain WS9154 and isogenic mutant strain WS9156, deleted in RAD17 gene. In these conditions, the DNA repair function is independent of division delay, since the analysed cells are fixed in G1 (Figs. 1, 2 and 3).

Previously, and using the same diploid strains, we demonstrated that the Rad17 protein is essential for DBS repair in the early stationary phase and during LH, after exposure to 1,000 Gy in the presence of nitrogen [11]. On the other hand, the cycling rad17/rad17 mutant cells showed no DBS repair in utrient medium, upon exposure to low doses of radiomimetic bleomycin, indicating the dual function of this gene in checkpoint determination and DNA repair [9]. Other authors using the diploid WS9131 strain (extensively isogenic to WS9154, see Section 2) and the SX46A haploid strain, showed that the resistant component of survival curves corresponding to stationary haploid and diploid cells depends on the RAD52 gene product, thus, on homologous recombination (HR). In the haploid SX46A strain, no influence of the RAD52 gene on survival of G1 stationary cells was observed. Interestingly, and in accordance with the present results, the HDFI gene product was involved in radiation resistance only in the absence of HR in G1 haploid stationary cells and upon deletion of RAD52 in the resistant component of the cell populations [7]. In the present study, it was shown that the magnitudes of LH survival and DBS repair of the stationary SX46A (more than 95% G1 cells), depended on the HDF1 gene, and were significantly lower than in the case of the diploid WS9154 (no possibility of sister chromatid exchange, nor of homologous chromosome exchange; compare Figs. 1, 2, 4 and 5, see Table 1).

In the late stationary phase, according to present results, the main pathways for DBS repair during LH include Rad17 and Hdf1 in diploid and haploid yeast, respectively. In haploids, the main pathway involved in the DNA damage response is NHEJ. In the diploid state, the induction of LH recovery requires the function of Rad17 complex, most probably in coordination with Mec1-Rad53-Rad 55-Rad57 inducible HR [9, 19]. The contribution to HR by an inducible pathway including MEC1, RAD53 and RAD 55 was indicated by other authors on the basis of molecular data. In fact, Rad55 phosphorylation in response to gamma ray damage depended on Mec1 and Rad53 checkpoint kinases and was essential for DNA damage-induced recombination [19].

The present results and the data we have mentioned from the literature are compatible with the action of a network of DBS repair pathways expressed upon different ploidies and different magnitudes of DNA damage upon combined nutrient stress and radiation damage (see Fig. 7).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Lourdes Blanc for expert technical assistance. This work was supported in part by PEDECIBA and Universidad de la República, Uruguay.

References

- 1.Hartwell, L., Weinert, T.A.: Checkpoints: controls that ensure the order of cell cycle events. Science 246, 629–634 (1989). doi:10.1126/science.2683079 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Elledge, S.J.: Cell cycle checkpoints: preventing an identity crisis. Science 274, 1664–1672 (1996). doi:10.1126/science.274.5293.1664 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Nyberg, K.A., Michelson, R.J., Putnam, C.W., Weinert, T.A.: Toward maintaining the genome: DNA damage and replication checkpoints. Annu. Rev. Genet. 36, 617–656 (2002). doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.36.060402.113540 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Zhang, H., Zhu, Z., Vidanes, G., Mbangkollo, D., Liu, Y., Siede, W.: Characterization of DNA damage-stimulated self-interaction of Saccharomyces cerevisiae checkpoint protein Rad17p. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 26715–16723 (2001). doi:10.1074/jbc.M103682200 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Majka, J., Burgers, P.M.: Yeast Rad17/Mec3/Ddc1: a sliding clamp for the DNA damage checkpoint. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 2249–2254 (2003). doi:10.1073/pnas.0437148100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Friedberg, E.C., Walker, G.C., Siede, W., Schutz, R.A., Ellenberger, T.: In: DNA repair and mutagenesis, 2nd edn, pp. 711–717. ASM, Washington (2006)

- 7.Siede, W., Friedl, A.A., Dianova, I., Eckardt-Schupp, F., Friedberg, E.C.: The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ku autoantigen homologue affects radiosensitivity only in the absence of homologous recombination. Genetics 142, 91–102 (1996) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Werner-Washburne, M., Braun, E., Johnston, G.C., Singer, R.A.: Stationary phase in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Rev. 57, 383–401 (1993) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Bracesco, N., Candreva, E.C., Keszenman, D., Sánchez, A.G., Soria, S., Dell, M., Siede, W., Nunes, E.: Roles of Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAD17 and CHK1 checkpoint genes in the repair of double strain breaks in cycling cells. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 46, 401–407 (2007). doi:10.1007/s00411-007-0119-y [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Friedl, A., Kiechle, M., Fellerhoff, B., Eckardt-Schupp, F.: Radiation-induced chromosome aberrations in S. cerevisiae: influence of DNA repair pathways. Genetics 148, 975–988 (1998) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Nunes, E., Bracesco, N., Candreva, E., Keszenman, D., Salvo, V., Siede, W.: Checkpoint determinant and DNA repair: dual function of the RAD17 gene of S. cerevisiae. In: Abstracts of the XIV International Biophysics Congress, IUPAB, Buenos Aires, p. 43 (2002)

- 12.Geigl, E.M., Eckardt-Schupp, F.: The repair of double-strand breaks and S1 nuclease-sensitive sites can be monitored chromosome-specifically in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Mol. Microbiol. 5, 1615–1620 (1991). doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01908.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Keszenman, D., Candreva, E., Nunes, E.: Cellular and molecular effects of bleomycin are modulated by heat shock in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat. Res. 459, 29–41 (2000) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Friedberg, E.C., Walker, G.C., Siede, W., Schutz, R.A., Ellenberger, T.: In: DNA repair and mutagenesis, 2nd edn, p. 666. ASM, Washington (2006)

- 15.Baur, M.: Analyse der Rolle von Glutathion bei der Induktion und Reparatur von Doppelstrangbrueche mit Hilfe der Puls-Feld-Gelelektrophorese in Hefe. Dissertation, Ph.D. Thesis, Biology Faculty, L-Maximilians University, Munich, Germany (1990)

- 16.Keszenman, D.J., Candreva, E.C., Sánchez, A.G., Nunes, E.: RAD6 gene is involved in heat shock induction of bleomycin resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 45, 36–43 (2005). doi:10.1002/em.20083 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Sánchez, Y., Desany, B.A., Jones, W.J., Liu, Q., Wang, B., Elledge, S.J.: Regulation of RAD53 by the ATM-like kinases MEC1 and TEL1 in yeast cell cycle checkpoint pathways. Science 271, 357–360 (1996). doi:10.1126/science.271.5247.357 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Lowndes, N.F., Murguia, J.R.: Sensing and responding to DNA damage. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 10, 17–25 (2000). doi:10.1016/S0959-437X(99)00050-7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Bashkirov, V., King, J., Bashkirova, E., Schmuckli-Maurer, J., Heyer, W.: DNA repair protein Rad55 is a terminal substrate of the DNA damage checkpoints. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 4393–4404 (2000). doi:10.1128/MCB.20.12.4393-4404.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Lewis, L.K., Resnik, M.A.: Tying up loose ends: nonhomologous end-joining in Sacharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat. Res. 451, 71–89 (2000). doi:10.1016/S0027-5107(00)00041-5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Palmbos, P.L., Daley, J.M., Wilson, T.E.: Mutations of the Yku80 C terminus and Xrs2 FHA domain specifically block yeast nonhomologous end joining. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 10782–10790 (2005). doi:10.1128/MCB.25.24.10782-10790.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.De la Torre-Ruiz, M.A., Lowndes, N.A.: The Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA damage checkpoint is required for efficient repair of double strand breaks by non-homologous end joining. FEBS Lett. 467, 311–315 (2000). doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(00)01180-7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Soutoglou, E., Misteli T.: Activation of the cellular DNA damage response in the absence of DNA lesions. Science 320, 1507–1510 (2008). doi:10.1126/science.1159051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]