Abstract

Objective

To examine relationships of age, period, and birth cohort to the 5-year incidence of age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

Design

Population-based cohort study with 4 examination visits 5 years apart in 1988–1990, 1993–1995, 1998–2000, and 2003–2005.

Participants

2,968 persons (6,603 participant visits) and 3,588 persons (8,184 participant visits) 43–86 years of age at baseline contributing to the incidence of early and late AMD, respectively.

Methods

Grading of stereoscopic fundus photographs using the Wisconsin Age-Related Maculopathy Grading System.

Main Outcome Measures

5-year incidence of early AMD.

Results

While controlling for age, there was a lower 5-year incidence of early AMD in later than earlier birth cohorts (odds ratio per increasing category, 0.70; 95% confidence interval, 0.62–0.78; P < 0.001). This remained while controlling for smoking, blood pressure, and other related factors. There was no evidence for a period or birth cohort effect with late AMD.

Conclusions

Lower incidence of early AMD in more recent birth cohorts is likely due to unmeasured risk factors for early AMD. Further study of possible unmeasured risk factors that may have caused this cohort effect may help identify new modifiable risk factors for AMD. Diminishing incidence of early AMD in later birth cohorts would be expected to result in lower long-term estimates of future incidence of AMD than current estimates that do not take this effect into account.

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the most common cause of vision loss in adult white Americans.1 The prevalence of AMD, based on data from population-based epidemiological studies, is assumed to be increasing in the United States and elsewhere, in part, because of the increasing longevity of the population.2 Independent of age, other factors, such as cigarette smoking, hypertension, inflammation, multivitamin use, and alcohol consumption, have been shown to be associated with AMD in some, but not all, studies.3

Based on three examinations of the Beaver Dam cohort, there appeared to be a birth cohort effect for the prevalence of early AMD at the time of the 10-year follow-up not explained by risk factors measured at baseline or in a time-dependent approach.4 This cohort effect was assumed to be due to differences in past exposures to unmeasured risk factors. There have now been 15 years of follow-up of the cohort. We now examine the relationships of age, period, and birth cohort to the 5-year incidence of early and late AMD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Population

Methods used to identify the population and description of the population have appeared in previous reports.5–9 Of the 5,924 enumerated persons 43–84 years of age ascertained in a private census from 1987 to 1988, 4,926 participated in the baseline examination in 1988 to 1990.5,6 Greater than 80% of the surviving eligible group (had AMD assessed in at least 2 successive exams) has participated in the 5-year (N=3,722), 10-year (N=2,962), and 15-year N=2,375) follow-up examinations. Comparisons between participants and nonparticipants at each of the examinations appear elsewhere.6–9

Procedures

Similar procedures were used at baseline and follow-up examinations.10–17 Informed signed consent was obtained and Institutional Review Board approval was given by the University of Wisconsin-Madison at the beginning of each examination. Pertinent parts of the examination at both baseline and follow-up examinations consisted of administering a questionnaire to obtain information on demographic characteristics and physical conditions, using standardized protocols for measuring blood pressure, height and weight, and taking stereoscopic 30° color fundus photographs centered on the disc (Diabetic Retinopathy Study DRS] standard field 1) and macula (DRS standard field 2) and a non-stereoscopic color fundus photograph temporal to but including the fovea of each eye. Details of the grading procedure have been described previously.10–12

Definitions

Definitions of the incidence of early and late AMD have been presented elsewhere.10–12 In brief, the incidence of early AMD was defined by the presence of either soft indistinct drusen, or the presence of retinal pigment epithelium depigmentation, or increased retinal pigment together with any type of drusen at follow-up when none of these lesions was present at baseline. The incidence of late AMD was defined by the appearance of either exudative macular degeneration or pure geographic atrophy at follow-up when neither lesion was present at baseline.

The birth cohort (or period) effect was defined as the variation in the incidence of AMD that arose from the different exposures of each birth (period) cohort. In this report, we are also interested in whether the birth (period) cohort effect remains while adjusting for identified risk factors. Birth cohorts were identified categorically by year of birth (1903–07, 1908–12, 1913–17, 1918–22, 1923–27, 1928–32, 1933–37, 1938–42). Periods were identified categorically by the calendar year of the initial examination to identify incidence of AMD (1988–90, 1993–95, 1998–2000). Similarly, age was identified categorically in 5-year bands of the current age at the initial examination to identify incidence of AMD (43–44, 45–49, …, 85–89, 90–94 years).

During the examination, a questionnaire was administered to assess history of smoking, drinking, physical activity, and vitamin and medication use. A subject was classified as a current smoker if he/she had smoked more than 100 cigarettes in his/her lifetime and had not stopped smoking; as a former smoker if he/she had smoked more than this number but had not smoked within the last year prior to the examination; and as a nonsmoker if he/she had smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in his/her lifetime. Pack years smoked was defined as the average number of cigarettes smoked per day divided by 20, multiplied by the number of years smoked. A current heavy drinker was defined as a person consuming four or more servings of alcoholic beverages daily, a former heavy drinker had consumed four or more servings daily in the past but not in the previous year, and a non-heavy drinker had never consumed four or more servings daily on a regular basis. Vitamin use was defined categorically as none, currently taking a single or other combination of vitamins (e.g., B-complex), or currently taking a multi-vitamin. Blood pressure was measured with a random-zero sphygmomanometer according to the Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program protocol, and the average of the two measurements was used for analysis.13 Mean arterial blood pressure was defined as diastolic pressure + 1/3 (systolic – diastolic blood pressure). Height and body weight were measured with participants wearing light clothing and no shoes. Body mass index was defined as weight in kilograms divided by the height in meters squared. Obesity was defined as body mass index greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2. Participants were asked if they engaged in a regular activity long enough to work up a sweat. Persons who on average did such activities less than three times a week were considered to have a sedentary lifestyle. For the purpose of this report, persons were asked to categorize their total household income (< $1,000 (K), 1–4K, 5–9K, 10–19K, 20–29K, 30–44K, 45–59K, > 60K) and highest year of education achieved (0–11 years, 12 years, 13–15 years, 16 + years).

Statistical Methods

SAS version 9 was used for analyzing the data (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Included in the analyses were 2,968 participants (6,603 participant-visits) for the incidence of early AMD and 3,588 participants (8,194 participant-visits) for the incidence of late AMD. Differences in denominators reflected differences in those at risk (for incident early AMD included only persons with no AMD while for late AMD included those with no or early AMD).

Data were structured such that each participant contributed data for one to three 5-year intervals depending on their participation and whether or not they had previously obtained the AMD outcome. Effects of age, period, and birth cohort were assessed using logistic regression models. Because age, period, and birth cohort are linearly dependent, effects of age, period, and birth cohort are not identifiable in a single model without further assumptions. We categorized age and birth year into 5-year bands. Pair-wise combination models (age and period, age and birth cohort) were investigated with continuous, categorical, and ordered factor effects. Akaike’s information criterion was used to determine the best fitting model.18

Multivariate models were employed by including variables that have been shown in other studies to have an effect on period, birth cohort, or AMD. We identified the following as characteristics that could potentially influence the relation between birth (period) cohort and the incidence of AMD: age at the examination, gender, history of smoking status and pack years smoked, heavy alcohol use, vitamin use, sedentary lifestyle, income and education level, mean arterial blood pressure, anti-hypertensive medication use, and obesity. Interactions were explored between birth cohort and each of these potential confounders by including appropriate interaction terms in the model.

RESULTS

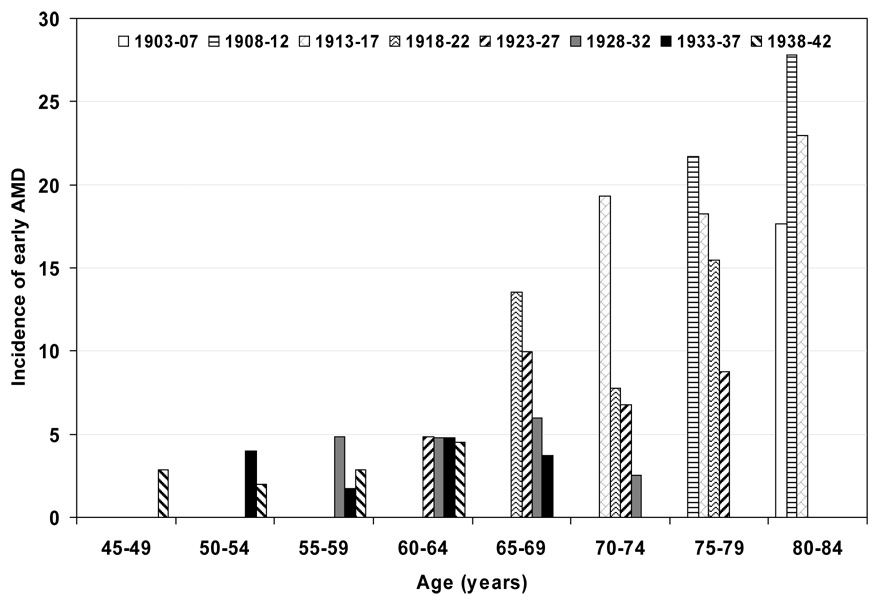

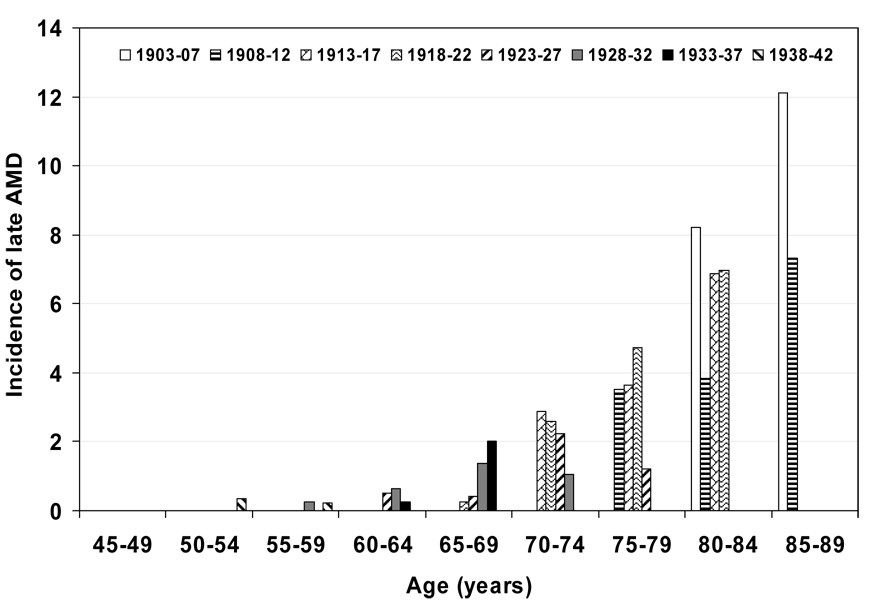

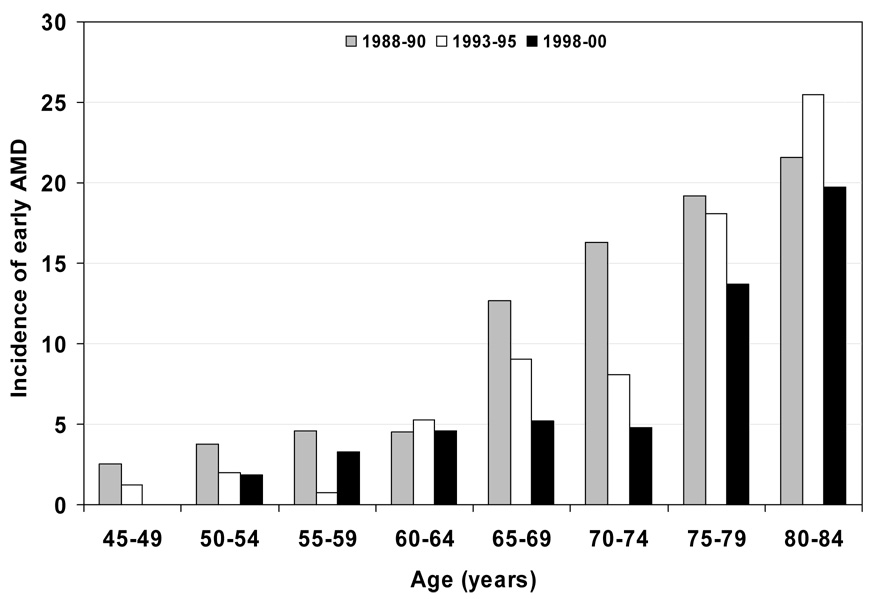

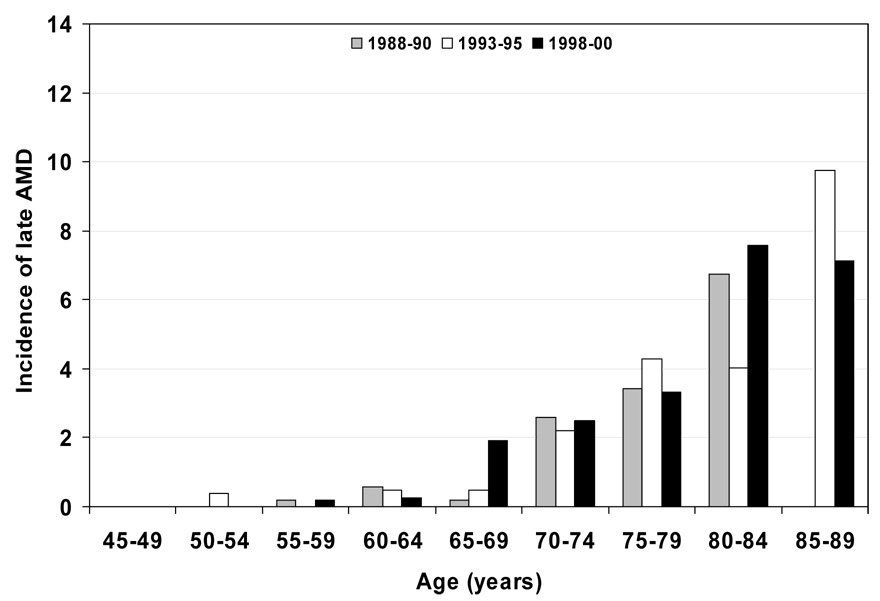

Characteristics of the population at the start of each examination are shown in Table 1. Persons examined at later examinations were less likely to have a history of being current smokers, heavy drinkers, have less education, less income, and more likely to have lower mean arterial blood pressures and have a history of using antihypertensive medications than those seen at earlier examinations. The 5-year incidences of early and late AMD are shown by age and birth cohort (Figure 1 and Figure 3 and Table 2) and age and period (Figure 2 and Figure 4 and Table 3). For most age groups, there was a lower 5-year incidence of early AMD in later birth cohorts or periods. For example, the 5-year incidence rates of early AMD in people examined when they were 65–69 years of age was 14% among those born in 1918–22, 10% among those born in 1923–27, 6% among those born in 1928–32, and 4% among those born in 1933–37.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Population at the Start of Each Examination Phase.

| Characteristic | Baseline 1988–90 N=3,494 Mean (SD) |

BDES2 1993–95 N=2,635 Mean (SD) |

BDES3 1998–00 N=2,067 Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 59.9 (10.2) | 63.0 (9.5) | 66.4 (8.6) |

| Sex, % male | 43.9 | 43.2 | 41.9 |

| Smoking history | |||

| Past, % | 35.7 | 39.4 | 43.0 |

| Current, % | 19.3 | 13.5 | 10.4 |

| Pack years smoked | 16.7 (25.4) | 15.0 (23.5) | 14.7 (23.5) |

| Heavy drinking history | |||

| Past, % | 14.0 | 14.9 | 13.3 |

| Current, % | 2.2 | 1.9 | 1.4 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.8 (5.4) | 29.6 (5.5) | 30.2 (5.9) |

| Mean arterial blood pressure, mmHg | 95.4 (11.7) | 93.8 (11.7) | 93.4 (11.2) |

| < High school education, % | 23.4 | 18.7 | 15.2 |

| < $10,000/year household income, % | 12.2 | 7.5 | 5.1 |

| Vitamin use | |||

| Single or non-standard combination | 9.0 | 19.4 | 21.7 |

| Multivitamin | 25.4 | 29.1 | 46.0 |

| Sedentary lifestyle, % | 74.0 | 70.1 | 70.3 |

| Anti-hypertensive use, % | 33.4 | 38.9 | 50.5 |

Abbreviations: SD=standard deviation; BDES=Beaver Dam Eye Study.

Figure 1.

5-year incidence of early age-related macular degeneration (AMD) by age and birth cohort. Note: data only displayed for subgroups with 30 or more persons; for numbers of persons at risk see Table 2.

Figure 3.

5-year incidence of late age-related macular degeneration (AMD) by age and birth cohort. Note: data only displayed for subgroups with 30 or more persons; for numbers of persons at risk see Table 2.

Table 2.

Five-year incidence of AMD by age and birth year in the Beaver Dam Eye Study.

| 5-year incidence of early AMD |

5-year incidence of late AMD |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Calendar Year Of Birth | N | % | N | % |

| 45–49 | 1938–1942 | 387 | 2.8 | 427 | 0.0 |

| 50–54 | 1933–1937 | 352 | 4.0 | 390 | 0.0 |

| 1938–1942 | 506 | 2.0 | 566 | 0.4 | |

| 55–59 | 1928–1932 | 331 | 4.8 | 390 | 0.3 |

| 1933–1937 | 401 | 1.7 | 459 | 0.0 | |

| 1938–1942 | 416 | 2.9 | 461 | 0.2 | |

| 60–64 | 1923–1927 | 310 | 4.8 | 387 | 0.5 |

| 1928–1932 | 379 | 4.7 | 460 | 0.7 | |

| 1933–1937 | 335 | 4.8 | 381 | 0.3 | |

| 1938–1942 | 111 | 4.5 | 125 | 0.0 | |

| 65–69 | 1918–1922 | 281 | 13.5 | 371 | 0.3 |

| 1923–1927 | 361 | 10.0 | 461 | 0.4 | |

| 1928–1932 | 284 | 6.0 | 362 | 1.4 | |

| 1933–1937 | 81 | 3.7 | 99 | 2.0 | |

| 70–74 | 1913–1917 | 197 | 19.3 | 279 | 2.9 |

| 1918–1922 | 257 | 7.8 | 384 | 2.6 | |

| 1923–1927 | 236 | 6.8 | 311 | 2.3 | |

| 1928–1932 | 79 | 2.5 | 95 | 1.1 | |

| 75–79 | 1908–1912 | 83 | 21.7 | 142 | 3.5 |

| 1913–1917 | 126 | 18.3 | 220 | 3.6 | |

| 1918–1922 | 149 | 15.4 | 212 | 4.7 | |

| 1923–1927 | 57 | 8.8 | 83 | 1.2 | |

| 80–84 | 1903–1907 | 34 | 17.6 | 73 | 8.2 |

| 1908–1912 | 54 | 27.8 | 104 | 3.8 | |

| 1913–1917 | 61 | 23.0 | 102 | 6.9 | |

| 1918–1922 | 29 | 13.8 | 43 | 7.0 | |

| 85–89 | 1903–1907 | 12 | 33.3 | 33 | 12.1 |

| 1908–1912 | 16 | 31.3 | 41 | 7.3 | |

| 1913–1917 | 8 | 0.0 | 14 | 7.1 | |

| 90–94 | 1903–1907 | 1 | 100.0 | 5 | 20.0 |

| 1908–1912 | 1 | 0.0 | 4 | 25.0 | |

Abbreviation: AMD=age-related macular degeneration

Figure 2.

5-year incidence of early age-related macular degeneration (AMD) by age and period. Note: data only displayed for subgroups with 30 or more persons; for numbers of persons at risk see Table 3.

Figure 4.

5-year incidence of late age-related macular degeneration (AMD) by age and period. Note: data only displayed for subgroups with 30 or more persons; for numbers of persons at risk see Table 3.

Table 3.

Five -year incidence of AMD by age and time period in the Beaver Dam Eye Study.

| 5-year incidence of early AMD | 5-year incidence of late AMD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Year of Started Interval | N | % | N | % |

| <45 | 1988–90 | 88 | 0.0 | 91 | 0.0 |

| 45–49 | 1988–90 | 553 | 2.5 | 604 | 0.0 |

| 1993–95 | 81 | 1.2 | 86 | 0.0 | |

| 50–54 | 1988–90 | 500 | 3.8 | 554 | 0.0 |

| 1993–95 | 496 | 2.0 | 547 | 0.4 | |

| 1998–2000 | 54 | 1.9 | 58 | 0.0 | |

| 55–59 | 1988–90 | 434 | 4.6 | 510 | 0.2 |

| 1993–95 | 395 | 0.8 | 451 | 0.0 | |

| 1998–2000 | 457 | 3.3 | 499 | 0.2 | |

| 60–64 | 1988–90 | 421 | 4.5 | 519 | 0.6 |

| 1993–95 | 343 | 5.2 | 422 | 0.5 | |

| 1998–2000 | 371 | 4.6 | 412 | 0.2 | |

| 65–69 | 1988–90 | 387 | 12.7 | 511 | 0.2 |

| 1993–95 | 332 | 9.0 | 415 | 0.5 | |

| 1998–2000 | 288 | 5.2 | 367 | 1.9 | |

| 70–74 | 1988–90 | 270 | 16.3 | 387 | 2.6 |

| 1993–95 | 248 | 8.1 | 362 | 2.2 | |

| 1998–2000 | 251 | 4.8 | 320 | 2.5 | |

| 75–79 | 1988–90 | 120 | 19.2 | 205 | 3.4 |

| 1993–95 | 127 | 18.1 | 210 | 4.3 | |

| 1998–2000 | 168 | 13.7 | 242 | 3.3 | |

| 80–84 | 1988–90 | 51 | 21.6 | 104 | 6.7 |

| 1993–95 | 51 | 25.5 | 99 | 4.0 | |

| 1998–2000 | 76 | 19.7 | 119 | 7.6 | |

| 85–89 | 1988–90 | 3 | 33.3 | 7 | 14.3 |

| 1993–95 | 16 | 25.0 | 41 | 9.8 | |

| 1998–2000 | 19 | 21.1 | 42 | 7.1 | |

| 90–94 | 1993–95 | 1 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.0 |

| 1998–2000 | 2 | 50.0 | 8 | 25.0 | |

Abbreviation: AMD=age-related macular degeneration

We present models for having age and birth cohort as categorical and, in addition, ordered factor variables (Table 4). The 5-year incidence of early AMD was lower for most later birth cohorts compared to earlier birth cohorts, with the strongest effects seen in 1918–22 vs 1913–17 and 1923–1927 compared to the 1918–1922 cohorts. Models containing age and birth cohort, both as ordered factor variables, provided the best fit for both early and late AMD. Later birth cohorts had lower incidence of early AMD (odds ratio [OR] 0.70; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.62–0.78; P < 0.001), while increasing categories of age were not significantly related to incident early AMD (OR 1.08; 95% CI, 0.96–1.21; P = 0.21). Similar associations were found for two lesions characterizing early AMD, retinal pigmentary abnormalities and soft indistinct drusen (data not shown). In contrast, birth cohorts were not related to incidence of late AMD (OR 0.96; 95% CI, 0.78–1.20; P = 0.74), while age was significantly related to incident late AMD (OR 1.86; 95% CI, 1.49–2.33; P < 0.001). Similarly, there was not a significant association of birth cohort, geographic atrophy and neovascular AMD (data not shown). In models including period as opposed to birth cohort, there was a significant relationship such that persons at later periods had lower incidence of early AMD than those at earlier periods (data not shown).

Table 4.

Age and Birth Cohort Models for Incidence of Early and Late AMD.

| Incidence of Early AMD |

Incidence of Late AMD |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contrast | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 50–54 vs 45–49 | 0.91 (0.42–1.94) | 0.80 | CNE* | |

| 55–59 vs 50–54 | 0.97 (0.56–1.69) | 0.91 | 0.72 (0.09–5.49) | 0.75 |

| 60–64 vs 55–59 | 1.26 (0.79–2.03) | 0.33 | 3.31 (0.61,17.88) | 0.16 |

| 65–69 vs 60–64 | 1.44 (0.98–2.13) | 0.07 | 1.76 (0.58–5.34) | 0.31 |

| 70–74 vs 65–69 | 0.68 (0.47–0.97) | 0.03 | 3.20 (1.45–7.07) | 0.004 |

| 75–79 vs 70–74 | 1.32 (0.91–1.94) | 0.15 | 1.55 (0.85–2.83) | 0.15 |

| 80–84 vs 75–79 | 1.10 (0.68–1.77) | 0.70 | 1.60 (0.81–3.15) | 0.18 |

| 85–89 vs 80–84 | 1.07 (0.46–2.49) | 0.88 | 1.50 (0.62–3.62) | 0.37 |

| 90–94 vs 85–90 | 0.34 (0.02–5.97) | 0.46 | 0.37 (0.06–2.11) | 0.26 |

| Age- ordered factor† | 1.08 (0.96–1.21) | 0.21 | 1.86 (1.49–2.33) | <0.001 |

| Year of Birth | ||||

| 1908–12 vs 1903–07 | 1.16 (0.52–2.62) | 0.72 | 0.58 (0.24–1.40) | 0.23 |

| 1913–17 vs 1908–12 | 0.86 (0.53–1.40) | 0.54 | 1.33 (0.63–2.79) | 0.46 |

| 1918–22 vs 1913–17 | 0.53 (0.36–0.77) | <0.001 | 0.98 (0.53–1.78) | 0.94 |

| 1923–27 vs 1918–22 | 0.63 (0.44–0.90) | 0.01 | 0.70 (0.34–1.46) | 0.35 |

| 1928–32 vs 1923–27 | 0.72 (0.49–1.07) | 0.10 | 1.75 (0.71–4.32) | 0.23 |

| 1933–37 vs 1928–32 | 0.79 (0.50–1.26) | 0.32 | 0.60 (0.15–2.51) | 0.49 |

| 1938–42 vs 1933–37 | 1.21 (0.72–2.02) | 0.47 | 0.59 (0.10–3.29) | 0.54 |

| Birth year- ordered factor† | 0.70 (0.62–0.78) | <0.001 | 0.96 (0.78–1.20) | 0.74 |

Abbreviations: AMD=age-related macular degeneration; OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval.

CNE=Cannot estimate.

Ordered factor effects were fit using the categorical variable as a linear effect in separate model.

Multivariate models for each AMD outcome controlling for potential confounders are shown in Table 5. The birth cohort and age effects did not change much from the unadjusted models. Further controlling for other factors not significantly related to birth cohort (e.g., current smoking) did not affect the results (data not shown). There were no significant interactions between birth cohort and age, sex, education, smoking, vitamin or medication use and the incidence of early or late AMD (data not shown).

Table 5.

Multivariate Generalized Estimating Equation Models for 5-year Incidence of Early and Late AMD.

| Incidence of Early AMD |

Incidence of Late AMD |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR 95% CI | P-value | OR 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age-ordered factor* | 1.06 (0.94–1.20) | 0.32 | 1.37 (1.04–1.82) | 0.03 |

| Birth year-ordered factor† | 0.70 (0.62–0.79) | <0.001 | 0.96 (0.74–1.26) | 0.78 |

| Male sex | 0.88 (0.69–1.11) | 0.27 | 0.85 (0.49–1.48) | 0.56 |

| Education-ordered factor | 0.86 (0.76–0.96) | 0.01 | 0.94 (0.73–1.19) | 0.59 |

| Pack years smoked per 10 years | 1.03 (0.99–1.08) | 0.16 | 1.05 (0.95–1.15) | 0.34 |

| Mean arterial bp per 10 mmHg | 0.92 (0.83–1.01) | 0.06 | 0.89 (0.74–1.08) | 0.25 |

| BMI per 10 kg/m2 | 1.06 (0.96–1.18) | 0.22 | 1.26 (1.03–1.54) | 0.03 |

| Vitamin use | ||||

| Multivitamin vs never | 0.87 (0.68–1.11) | 0.25 | 0.97 (0.56–1.68) | 0.91 |

| Single/combination vs never | 1.01 (0.75–1.37) | 0.93 | 0.97 (0.53–1.76) | 0.91 |

| History of heavy drinking | ||||

| Current vs never | 1.29 (0.58–2.88) | 0.54 | 2.45 (0.62–9.73) | 0.20 |

| Past vs never | 0.79 (0.55–1.14) | 0.21 | 0.64 (0.27–1.50) | 0.31 |

| Baseline AMD severity | 7.26 (5.49–x9.59) | <0.001 | ||

Abbreviations: AMD=age-related macular degeneration; OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval; bp=blood pressure; BMI=body mass index.

Age groups (years): 45–49, 50–54, 55–59, 60–64, 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, 85–89.

Birth year groups: 1903–07, 1908–12, 1913–17, 1918–22, 1923–27, 1928–32, 1933–37, 1938–42.

DISCUSSION

Incidence of AMD is often examined by age strata. One advantage of the long-term study of population-based cohorts with multiple examinations is the opportunity to observe whether birth cohort or period affect this relation. In Beaver Dam, we found evidence of lower 5-year incidence of early but not late AMD in later birth and period cohorts. This is consistent with our earlier finding of a lower prevalence of early AMD in later compared to earlier birth cohorts.4 To our knowledge, no other studies have examined a cohort effect on incident AMD. There are many possible reasons why persons born in more recent years or seen in later periods have a lower incidence of early AMD than similarly aged persons born in earlier years or seen in earlier periods. One reason is that persons born at different times or seen in different periods may have differing exposures to factors (e.g., smoking, uncontrolled blood pressure, sedentary lifestyle, intake of multivitamins) and different patterns of care for conditions (e.g., inflammatory or infectious disease) that may affect the incidence of AMD. There may be different levels of vulnerability to such exposures at different times of life or at different stages of AMD. Of risk factors previously reported to be associated with the incidence of AMD, higher mean arterial blood pressure, greater obesity, more frequent history of past heavy drinking, less likelihood of taking vitamins, less income, and less education achieved was found in earlier than in later birth cohorts.3 Many of these findings reflect similar birth cohort effects reported in the United States and elsewhere.19–22 Less education and lower income in the earlier birth cohorts may be markers for unmeasured lifetime exposures to protective (e.g., dietary omega 3’s, leafy vegetables) or deleterious factors (e.g., exposure to diets with high glycemic index or diets high in saturated fats) that may account, in part, for the birth cohort effect found. However, when added to multivariable models, mean arterial blood pressure and education or income level resulted in no attenuation of the cohort effect. We cannot evaluate the effect of childhood and young adult exposures to infectious and inflammatory diseases (e.g., flu epidemic in 1918), patterns of cigarette smoke inhalation and characteristics of cigarette type smoked (tar, nicotine content), or dietary deprivation during periods like the Great Depression in the 1930s and their effect on the incidence of AMD in different birth cohorts. Furthermore, we can not differentiate birth cohort from period effects.

Current forecasts of 25-year estimates of prevalent early AMD are based on the assumption that the earlier observed trends will be similar in future years.2 However, this assumption may not be correct if decreasing incidence of AMD continues with each new birth cohort as observed in the Beaver Dam Eye Study cohort. Lower prevalence of AMD might be expected in the future because current estimates are based on existing data and do not take into account possible drops in incidence as more recently born cohorts age.

The current study, with AMD measured objectively from fundus photographs taken at four examinations 5 years apart in a large population-based cohort, provides data on the cohort effect for this condition. Nevertheless, the results from this study should be interpreted with caution. First, the study participants were white. Therefore, the results from this study may not apply to other racial/ethnic groups. Second, the current analysis was limited to participants who remained alive during each of the 5-year intervals of follow-up. It is possible that risk factors (e.g., education, diet, smoking) may have differentially affected the relationship between participation and mortality and incidence of AMD in different birth cohorts. We have not observed evidence of differences in participation among those at risk of AMD in the different birth and period cohorts making it less plausible that this would explain the reduction of incident AMD in later birth and period cohorts. Third, the power to detect an age-birth cohort and period effects for late AMD is somewhat limited by the low incidence of this outcome.

In summary, we found that persons born in more recent years or examined in a later period have a lower 5-year incidence of early AMD than similarly aged persons born earlier or examined in an earlier period. Observed differences in health care changes (e.g., better control of blood pressure, use of antihypertensive agents) and lifestyle changes (e.g., less smoking) over the previous 15 years do not explain these findings. It is not clear whether other exposures earlier in life (e.g., infectious disease outbreaks such as the flu pandemic of 1918), dietary restrictions specific to a period (e.g., Great Depression), or other unmeasured factors during later life could explain these birth cohort and period differences. Regardless, birth cohort and period effects should be monitored and taken into account when projecting estimates of future prevalence of AMD.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD) Grant No. EY06594, (R Klein, BEK Klein) and, in part, by Research to Prevent Blindness (R. Klein and BEK Klein, Senior Scientific Investigator Awards), New York, NY. The National Eye Institute provided funding for entire study including collection and analyses and of data; RPB provided further additional support for data analyses.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

None of the authors have any proprietary interests.

Reference List

- 1.The Eye Diseases Prevalence Research Group. Causes and prevalence of visual impairment among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:477–485. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman DS, O'Colmain BJ, Munoz B, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:564–572. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein R, Peto T, Bird A, Vannewkirk MR. The epidemiology of age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:486–495. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang GH, Klein R, Klein BE, Tomany SC. Birth cohort effect on prevalence of age-related maculopathy in the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:721–729. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linton KL, Klein BE, Klein R. The validity of self-reported and surrogate-reported cataract and age-related macular degeneration in the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:1438–1446. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klein R, Klein BE, Linton KL, De Mets DL. The Beaver Dam Eye Study: visual acuity. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1310–1315. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein R, Klein BE, Lee KE. Changes in visual acuity in a population. The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:1169–1178. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30526-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein R, Klein BE, Lee KE, et al. Changes in visual acuity in a population over a 10-year period : The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1757–1766. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00769-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein R, Klein BE, Lee KE, et al. Changes in visual acuity in a population over a 15-year period: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:539–549. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein R, Klein BE, Jensen SC, Meuer SM. The five-year incidence and progression of age-related maculopathy: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:7–21. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30368-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein R, Klein BE, Tomany SC, et al. Ten-year incidence and progression of age-related maculopathy: The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1767–1779. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein R, Klein BE, Knudtson MD, et al. Fifteen-year cumulative incidence of age-related macular degeneration: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein R, Klein BE. Manual of Operations. Springfield, VA: US Department of Commerce; 1991. The Beaver Dam Eye Study; pp. 74–112. NTIS Accession No. PB91-149823. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein R, Klein BE. Manual of Operations. Springfield, VA: US Department of Commerce; 1995. The Beaver Dam Eye Study II; pp. 61–90. NTIS Accession No. PB95-273827. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein R, Davis MD, Magli YL, et al. The Wisconsin Age-Related Maculopathy Grading System. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1128–1134. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein R, Davis MD, Magli YL, et al. The Wisconsin Age-Related Maculopathy Grading System. Springfield, VA: US Department of Commerce; 1991. pp. 8–46. NTIS Accession No. PB91-184267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein R, Klein BE, Linton KL. Prevalence of age-related maculopathy. The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:933–943. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31871-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akaike H. Information Theory and the Extension of the Maximum Likelihood Principle. In: Petrov VN, Csaki F, editors. Second International Symposium on Information Theory. Budapest: Akailseoniai-Kiudo; 1973. pp. 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vartiainen E, Jousilahti P, Alfthan G, et al. Cardiovascular risk factor changes in Finland, 1972–1997. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:49–56. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA. 2002;288:1723–1727. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore AA, Gould R, Reuben DB, et al. Longitudinal patterns and predictors of alcohol consumption in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:458–465. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.019471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ding J, Kritchevsky SB, Newman AB, et al. Effects of birth cohort and age on body composition in a sample of community-based elderly. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:405–410. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.2.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]