Abstract

Most clinical trials use 6 mo or 1 yr follow-ups as proxies for life-time smoking cessation. Retrospective studies have estimated 2–15% of smokers relapse each year after the first 1 year of abstinence, but these have methodological problems such as memory bias. We searched for prospective studies of adult quitters that reported the number of participants abstinent at 1 yr follow-up and who remained abstinent at ≥ 2 year follow-ups. We included studies that reported the percent who remained lapse-free, did not continue treatment after 1 yr, and had ≤ 10% lost to follow-up. We did not locate any population-based studies but did locate eight randomized, controlled trials, all testing nicotine medications. After deleting one trial with outlier results, a meta-analysis estimated the annual incidence of relapse after 1 yr to be 10%; however, the small sample sizes resulted in a wide 95% confidence interval (5–17%) suggesting this estimate is not very accurate. We conclude a non-significant amount of relapse occurs after 1 yr. Better quantification of this relapse rate is important to improve estimates of lifelong abstinence and reductions in morbidity and mortality from smoking cessation.

Keywords: Nicotine dependence, relapse, smoking, smoking cessation, tobacco, tobacco use disorder

1. Introduction

The goal of tobacco control policies and smoking cessation treatment among adult smokers is to induce life-long abstinence (Burns, 2000; US Department of Health and Human Services, 1990). Most clinical trials and cohort studies use 6 mo or 1 yr follow-ups as proxy measures to estimate life-long abstinence (Pierce & Gilpin, 2003). Few trials have examined abstinence after 1 yr (Etter & Stapleton, 2006).

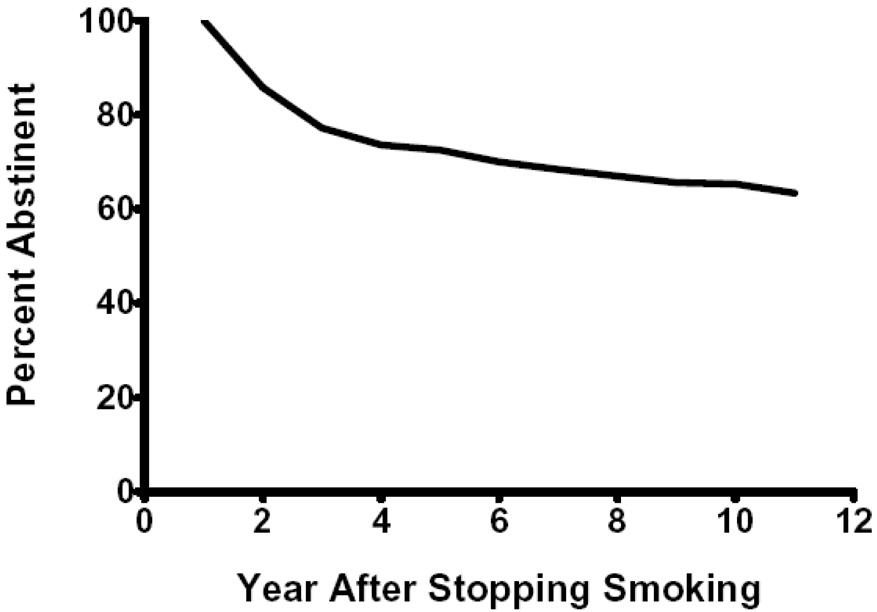

Whether 1 yr follow-ups are good proxies for lifelong abstinence depends on how much relapse occurs after 1 yr. Relapse to smoking after a quit attempt is greatest in the first few weeks and decreases rapidly over time (Hughes, Keely, & Naud, 2004). In retrospective data sets of non-treatment samples, among those abstinent at 1 yr, 2–15% relapse each year thereafter (Gilpin, Pierce, & Farkas, 1997; Hammond & Garfinkel, 1963; Hammond & Garfinkel, 1964; Kirscht, Brock, & Hawthorne, 1987; US Dept Health and Human Services, 1990). The best retrospective estimate of relapse was from the population-based US National Health and Nutrition Examination Study (NHANES) Follow-up Study done in 1982–1984 (Figure 1) (US Dept Health and Human Services, 1990). The percent of 1 yr abstainers who relapsed in the second and third years were 14% and 10% and this decreased to < 5% in the years thereafter. Although the NHANES survey has the asset of using a large, representative sample, it was collected over 20 yrs ago and was reported only in an appendix of the 1990 Surgeon General’s Report. Perhaps more importantly, retrospective reports of abstinence are often invalid, especially when they require recall of events occurring several years previously (Gilpin & Pierce, 1994).

Figure 1.

Retrospective reports of relapse after 1 yr of abstinence from the 1982–1984 US National Health and Nutrition Examinations Study.

A few prospective studies have examined long-term follow-up. A recent review of 12 studies of nicotine replacement (NRT) efficacy focused on whether efficacy (i.e. odds ratio) persisted after 1 yr (Etter et al., 2006). Our analyses of data from Table 3 of that article indicates 31% in the placebo group and 33% in the active group relapsed between the 1 yr follow-up and the long-term follow-up; however, these rates are hard to interpret because the long-term follow-up varied widely (from 3–8 yrs) and the data do not allow determination of the annual rate of relapse. In addition, these estimates are likely inflated because the studies counted loss-to-follow-ups as relapses and several studies had rates of loss-to-follow-up of > 20%.

2. Methods

We searched for prospective (i.e. cohort) studies of relapse after 1 yr; these could include uncontrolled studies. We initially obtained possible studies via searching the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction database (www.cochrane.org), the database used in the 2000 USPHS Guideline (Fiore et al., 2000), and the first author’s collection of 16 other meta-analyses on smoking cessation treatments. We also searched Pub Med by searching for “(nicotin* OR tobacco OR smok*) AND (stop* OR quit* OR relaps* OR cessation) AND long” in the title of clinical trials. A similar search substituted the phrase “1 OR 2 OR 3 … OR 15” for the phrase “long”. These searches were limited to “clinical trials” in “humans”. Similar searches were conducted with PsychInfo, EMBASE, SSCI, and the Center for Disease Control Tobacco Information and Prevention Database. The author also asked those on the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco (SRNT) and College on Problems of Drug Dependence (CPDD) list-serves and those who authored relevant abstracts at recent CPDD, SRNT, National/World Congresses on Tobacco or Health, and Society for Behavioral Medicine meetings to send publications on this topic. This search resulted in 99 articles read by the first author.

3. Inclusion Criteria

Given that we are interested in relapse, we required report of prolonged abstinence (i.e., not point prevalence abstinence) both at the 1 yr and later follow-ups. When a study was unclear or stated the number/percent abstinent “at” a follow-up, we assumed this was point-prevalent abstinence. This requirement eliminated several large, population-based and semi-population based studies such as the Community Intervention Trial for Smoking Cessation (COMMIT Research Group, 1995). We also excluded studies whose treatment continued beyond 1 yr as this could influence relapse rates. This eliminated the Lung Health Study (Anthonisen et al., 1994) and the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (Hughes, Hymowitz, Ockene, Simon, & Vogt, 1981), both of which were large trials with multiple post-1yr follow-ups. To increase external validity, we excluded studies of “special populations”; e.g., of adolescents, pregnant smokers, elderly smokers, minority smokers and non-cigarette tobacco users. We excluded studies that had only 1.5 yr follow-ups because they would contribute little information.

Most studies assumed that those who could not be reached were smokers. In this scenario, high relapse rates could be solely due to low contact rates. For example, one study reported that almost all the “relapse” was due to loss of follow-ups (Richmond & Kehoe, 2007). We chose to exclude studies that had >10% lost-to-follow-up between contacts or that did not report the number lost-to-follow-up. Some trials used survival analyses which assumes those missing are not more likely to be smokers (Hosmer & Lemeshow, 1999). Given this is unlikely, (Hughes et al., 2003; Hall et al., 2001) we excluded these studies.

4. Results

We did not locate any natural history studies or population-based studies. We did locate eight prospective studies (reported via 12 articles) that met our inclusion criteria (Blondal, 1989; Blondal, Franzon, & Westin, 1997; Blondal, Gudmundsson, Olafsdottir, Gustavsson, & Westin, 1999; Clavel-Chapelon, Paoletti, & Benhamou, 1992; Clavel-Chapelon, Paoletti, & Benhamou, 1997; Glavas, rumboldt, & Rumboldt, 2003; Mikkelsen, Tonnesen, & Norregaard, 1994; Stapleton, Sutherland, & Russell, 1998; Sutherland et al., 1992; Tonnesen, Norregaard, & Sawe.U, 1992; Tonnesen et al., 1988; Tonnesen et al., 1992; Tonnesen, Norregaard, Simonsen, & Sawe, 1991). All of these studies were included in the Etter and Stapleton review (Etter et al., 2006); however, four of the trials in that earlier review were not included in our review because they had high rates of lost-to-follow-up. The first and second authors and two students read the articles and coded them for the variables in Table 1. The small amount of disagreement (<10%) was settled by a discussion between the two raters.

Table 1.

Prospective Studies of Relapse After 1 Year

| Study | Follow-ups (yrs) | Percentlost to f/u | Groups | Percent using active tx at 1 yr f/u | Fraction relapsed between 1 yr and last f/u | Percent relapsed/yr by tx group | Percent relapsed/yr in entire study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blondal 89 | 2 | 0% | Gum | 2% | 1/30 | 3% | 4% |

| Placebo | 1/22 | 5% | |||||

| Blondal, 97 | 2 | <1% | NNS | 45% | 5/20 | 25% | 21% |

| PIacebo | 2/13 | 15% | |||||

| Tonneson, 88 | 2 | <1% | 4mg Gum/High Dependence | 6% | 3/12 | 25% | 35% |

| 2mg Gum/High Dependence | 2/4 | 50% | |||||

| 2mg Gum/Low Dependence | 6/23 | 26% | |||||

| Placebo/Low Dependence | 7/12 | 58% | |||||

| Tonneson, 91 | 3 | 0% | Patch | 0% | 9/24 | 19% | 17% |

| Tonneson, 92 | Placebo | 2/7 | 14% | ||||

| Mikkelsen 94 | |||||||

| Sutherland, 92 | 3.5 | 10% | NNS | 43% | 5/33 | 6% | 11% |

| Stapleton, 98 | PIacebo | 8/14 | 23% | ||||

| Clavel, 92 | 4 | 3% | Placebo + Sham | 0% | 7/25 | 9% | 13% |

| Clavel, 97 | Placebo + Acupuncture | 4/18 | 7% | ||||

| Gum + Sham | 10/23 | 14% | |||||

| Gum + Acupuncture | 16/30 | 17% | |||||

| Glavas 03 | 5 | 0% | Patch | 0% | 3/13 | 6% | 5% |

| Placebo | 1/9 | 3% | |||||

| Blondal, 99 | 6 | 0% | Patch + NNS | 13% | 13/32 | 8% | 7% |

| Patch + Placebo | 3/13 | 5% |

F/u = follow up, NNS = nicotine nasal spray, Sham = sham acupuncture, tx = treatment, yr = year

All eight studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of NRT that had follow-ups ranging from 2–6 yrs post-quit date. The incidence of lost-to-follow-ups was essentially nil in seven studies. All but one study (Blondal, 1989) clearly stated they “confirmed” self-report via carbon monoxide levels. Only one study (Tonnesen et al., 1991) had more than one follow-up. The eight studies reported on 20 groups; i.e., on 12 treatment groups and 8 placebo groups. The sample sizes were small; the number of 1 yr quitters ranged from 4–33/study group and 31–96/study. In six of the studies, few or none were using NRT at one year follow-up. In two studies, almost half of participants were using NRT at the one-year; however, neither of these studies allowed NRT use beyond 1 yr (Table 1). Since the results of these two trials did not appear to differ from the other six, we included them. Studies varied on when the follow-up occurred; thus, to compare relapse incidence across studies, we converted results to the incidence of relapse/extra year after the 1 yr follow-up (nb--this comparison assumes relapse incidence does not decrease with longer follow-ups-- an issue we address in the discussion).

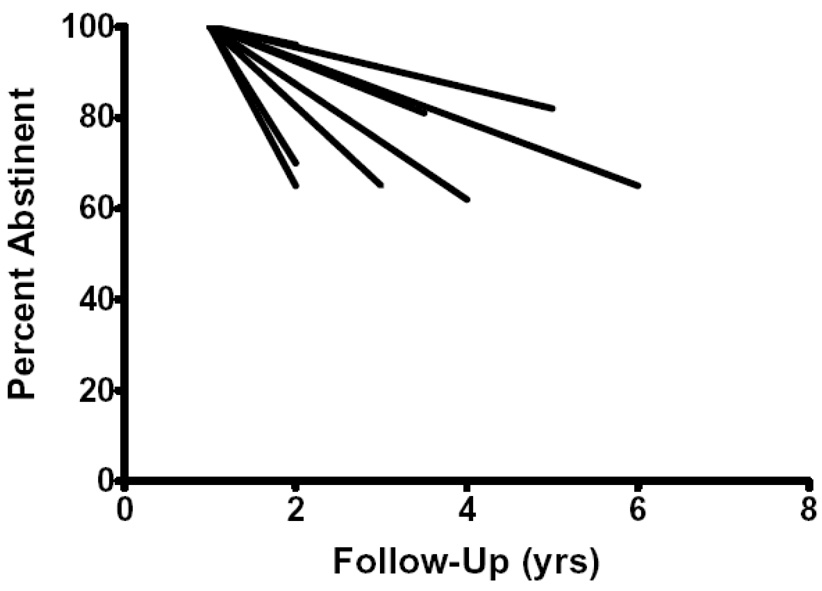

Across both study groups and studies, the annual incidence of relapse was typically <20% (Table 1). All but one of the studies reported relapse rates of <25%. One study (Tonnesen et al., 1988) appeared to be an outlier as it reported the four highest relapse rates in the data set (i.e. 25–50%). We attempted to collate the results by entering annual relapse rates for each of the 20 study groups into a meta-analysis (Einarson, 1997). Several incidence rates were near zero. To prevent these from having an inflated weight and bias the results, we used an arcsine transformation. Nevertheless, the chi-square test for homogeneity suggested the results were heterogeneous across study groups (p=.01) precluding an accurate meta-analytic estimate (Einarson, 1997). We deleted the one outlier study (Tonnesen et al., 1988) and the results remained heterogeneous. We thought some of the heterogeneity could be due to the small sample sizes; thus, we increased the sample size by making the study, not the experimental group, the unit of analysis. Since this required combining those who had previously been in active and placebo groups, we tested whether the incidence of relapse after 1 yr differed in these two treatments and it did not. The results across studies remained heterogeneous (p = .01). Finally, we repeated this study-based meta-analysis and deleted the outlier study. Although there remained some variability (see Figure 2), the results were statistically homogenous (p=.11) with a relapse rate of 10%/yr; however, the 95% CI was wide (5–17%) suggesting little accuracy.

Figure 2.

Prospective incidence of relapse after abstinence at 1 yr in trials that met inclusion criteria.

5. Discussion

Our major finding is the paucity of valid, generalizable, detailed estimates of the incidence of relapse after 1 yr. The validity of most studies that report long term follow-ups is compromised by their use of point prevalence outcomes, by high rates of lost-to-follow-ups, or by continued treatment after 1 yr. We did locate eight long-term studies that avoided these problems and report their results; however, the internal validity of these studies was limited by their small number and sample sizes, and their external validity was limited by their use of treatment seekers, which are a minority of smokers.

After deleting one study as an outlier, our meta-analysis estimated the incidence of relapse to be 10%/yr. This estimate is similar to the 10–14% relapse incidence reported in the second and third years of the NHANES survey (US Dept Health and Human Services, 1990) and to the 2–15% rates reported in other large retrospective studies (Gilpin et al., 1997; Hammond et al., 1963; Hammond et al., 1964; Kirscht et al., 1987; US Dept Health and Human Services, 1990). Although this 10% incidence of relapse may appear small, if it continues year after year, then, for example, after 5 yrs, 41% of 1 yr quitters would have relapsed. Our included studies did not have multiple follow-ups to test whether the incidence of relapse decreases over time. In the previously mentioned NHANES study and in two other large studies that did not meet our inclusion criteria (Anthonisen et al., 1994; Hughes et al., 1981; US Dept Health and Human Services, 1990), the incidence of relapse appeared to be less in later years, which would decrease concerns about the cumulative effect of late relapses. For the reasons listed above, we believe our estimate of 10% annual relapse rates should be considered preliminary.

In summary, our study suggests (a) the annual rate of relapse after 1 yr is likely substantial, especially when it cumulates over years, (b) annual relapse rates are likely to be near 10%, and (c) future estimates need to report prolonged abstinence outcomes, and invest time and effort to insure low rates of lost-to-follow-up. Improving the accuracy of the rate of post 1 yr relapse is especially important to determine how adequate 6 mo or 1 yr abstinence rates are as proxies for life-long abstinence. It is also important to improve calculations of the benefits of cessation or treatment on morbidity and mortality reduction (US Department of Health and Human Services, 1990). We would encourage those conducting either treatment or cohort studies to continue to follow abstinent smokers after 1 yr, and to report these outcomes.

Acknowledgements

This analysis was supported by NIDA Senior Scientist Award DA-00490(JRH) and Institutional Training Grant DA-07242(ENP)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anthonisen NR, Connett JE, Kiley JP, Altose MD, Bailey WC, Buist AS, Conway WA, Jr, Enright PL, Kanner RE, O'Hara P, Owens GR, Scanlon PD, Tashkin DP, Wise RA. Effects of smoking intervention and the use of an inhaled anticholinergic bronchodilator on the rate of decline of FEV. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;272:1497–1505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondal T. Controlled trial of nicotine polacrilex gum with supportive measures. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1989;149:1818–1821. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1989.00390080080018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondal T, Franzon M, Westin A. A double-blind randomized trial of nicotine nasal spray as an aid in smoking cessation. European Respiratory Journal. 1997;10:1585–1590. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10071585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondal T, Gudmundsson LJ, Olafsdottir I, Gustavsson G, Westin A. Nicotine nasal spray with nicotine patch for smoking cessation: Randomised trial with six year follow up. British Medical Journal. 1999;318:285–289. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7179.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns D. Population impact of smoking cessation: Proceedings of a conference on what works to influence cessation in the general population; Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Clavel-Chapelon F, Paoletti C, Benhamou S. A randomised 2X2 factorial design to evaluate different smoking cessation methods. Revue d'Epidemiologie et de Sante Publique. 1992;40:187–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clavel-Chapelon F, Paoletti C, Benhamou S. Smoking cessation rates 4 years after treatment by nicotine gum and acupuncture. Preventive Medicine. 1997;26:25–28. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.9997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COMMIT Research Group. Community Intervention Trial for Smoking Cessation (COMMIT): I. Cohort results from a four-year community intervention. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85:183–192. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.2.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einarson T. Pharmacoeconomic applications of meta-analysis for single groups using antifungal onychomycosis lacquers as an example. Clinical Therapeutics. 1997;19:559–569. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(97)80140-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etter J, Stapleton J. Nicotine replacement therapy for long-term smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. Tobacco Control. 2006;15:280–285. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.015487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, Dorfman SF, Goldstein MG, Gritz ER, Heyman RB, Jaen CR, Kottke T, Lando HS, Mecklenburg RE, Mullen PD, Nett LM, Robinson L, Stizer ML, Tommasello AC, Villejo L, Wewers ME. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Public Health Service; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin E, Pierce JP. Measuring smoking cessation: Problems with recall in the 1990 California Tobacco Survey. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 1994;3:613–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin EA, Pierce JP, Farkas AJ. Duration of smoking abstinence and success in quitting. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1997;89:572–576. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.8.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glavas D, Rumboldt M, Rumboldt Z. Smoking cessation with nicotine replacement therapy among health care workers: randomized double-blind study. Croatian Medical Journal. 2003;44:219–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SM, Delucchi K, Velicer WF, Kahler CW, Ranger-Moore J, Hedeker D, Tsoh J, Niaura R. Statistical analysis of randomized trials in tobacco treatment: Longitudinal designs with dichotomous outcome. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2001;3:193–203. doi: 10.1080/14622200110050411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond EC, Garfinkel L. The influence of health on smoking habits. National Cancer Institute Monograph. 1963;19:269–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond EC, Garfinkel L. Changes in cigarette smoking. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1964;33:49–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Survival Analysis: Regression Modeling of Time to Event Data. 1st Edition. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes GH, Hymowitz N, Ockene JK, Simon N, Vogt TM. The multiple risk factor intervention trial (MRFIT) Preventive Medicine. 1981;10:476–500. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(81)90061-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction. 2004;99:29–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Keely J, Niaura R, Ossip-Klein D, Richmond R, Swan G. Measures of abstinence from tobacco in clinical trials: Issues and recommendations. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2003;5:13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirscht JP, Brock BM, Hawthorne VM. Cigarette smoking and changes in smoking among a cohort of Michigan adults. American Journal of Public Health. 1987;77:501–502. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.4.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen KL, Tonnesen P, Norregaard J. Three-year outcome of two-and three-year sustained abstainers from a smoking cessation study with nicotine patches. Journal of Smoking-Related Disease. 1994;5:95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce J, Gilpin E. A minimum 6-month prolonged abstinence should be required for evaluating smoking cessation trials. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2003;5:151–153. doi: 10.1080/0955300031000083427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond R, Kehoe L. Ten-year survival outcome of the nicotine transdermal patch with cognitive behavioural therapy. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2007;31:282–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2007.00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton JA, Sutherland G, Russell MAH. How much does relapse after one year erode effectiveness of smoking cessation treatments? Long term follow up of randomised trial of nicotine nasal spray. British Medical Journal. 1998;316:830–831. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7134.830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland G, Stapleton JA, Russell MAH, Jarvis MJ, Hajek P, Belcher M, Feyerabend C. Randomised controlled trial of nasal nicotine spray in smoking cessation. Lancet. 1992;340:324–329. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91403-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonnesen P, Fryd V, Hansen M, Helsted J, Gunnersen A, Forchammer H, et al. Effect of nicotine chewing gum in combination with group counseling in the cessation of smoking. New England Journal of Medicine. 1988;318:15–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198801073180104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonnesen P, Norregaard J, Sawe U. Two-year outcome in a smoking cessation trial with a nicotine patch. Journal of Smoking Related Disease. 1992;3:241–245. [Google Scholar]

- Tonnesen P, Norregaard J, Simonsen K, Sawe U. A double-blind trial of a 16-hour transdermal nicotine patch in smoking cessation. New England Journal of Medicine. 1991;325:311–315. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108013250503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Rockville, MD: Office on Smoking & Health; The Health Benefits of Smoking Cessation. A Report of the US Surgeon General. 1990

- US Dept Health and Human Services. National trends in smoking cessation. Washington: U.S: Government Printing Office; The Health Benefits of Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General. 1990