Abstract

Introduction

Thrombomodulin (TM) is an important anti-coagulant protein that is down-regulated on endothelial cells overlying atherosclerotic plaques. We investigated the effects of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) ligands, fenofibrate and rosiglitazone, on the expression of TM ex vivo by advanced carotid atheromas, and in vitro by endothelial cells.

Methods

Adjacent carotid atheroma biopsies were incubated in vehicle control or PPAR ligand in explant culture for 4 days. Human aortic endothelial cells were incubated with PPAR ligands in vitro. TM expression was measured by Western blotting and flow cytometry. TM activity was assessed by generation of activated protein C.

Results

The PPAR-α activator, fenofibrate, up-regulated total TM expression within carotid explants by 1.7-fold (P<0.001) with no effect on activity. Rosiglitazone treatment had no effect on protein levels but reduced activity by 73% of the control (P<0.05). We noted disparate effects of PPAR ligands in atheroma samples from different patients and postulated that the response of endothelial cells to medication was influenced by the atheromatous environment. Incubation of human aortic endothelial cells with fenofibrate alone led to a dose-dependent increase in TM expression (P<0.05), however, in the presence of oxidized LDL a dose-dependent reduction in TM expression was induced by fenofibrate (P<0.05).

Conclusions

The ability of fenofibrate to increase endothelial cell and carotid atheroma TM protein expression suggests a potential therapeutic role for this medication. The response to PPAR ligands likely varies depending on the exact constituents of individual atherosclerotic plaques, such as the relative amount of oxidized LDL.

Keywords: Fenofibrate, rosiglitazone, thrombomodulin, atherosclerosis, endothelial cells

Thrombomodulin (TM) is a transmembrane anticoagulant glycoprotein expressed by endothelial cells and its secretion into the circulation has been associated with atherosclerosis as an indicator of endothelial cell stress [1–4]. TM binds thrombin which activates protein C, leading to the inhibition of two co-factors in the clotting cascade, FVa and FVIIIa [5, 6]. TM is down-regulated in atherosclerotic arteries [7] and circulating plasma levels have been positively correlated with symptomatic peripheral and coronary artery disease [8]. The reduced expression of TM in advanced atherosclerosis may play an important role in determining the occurrence of thrombo-embolic events during plaque rupture. Therapeutic methods of up-regulating TM expression could be of significant value [9].

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are transcription factors that control genes associated with lipid and lipoprotein metabolism, glucose homeostasis and inflammation [10]. A number of medication groups including the thiazolidinediones (TZDs) and the fibric acid derivative fenofibrate have been demonstrated to activate PPARs and have pleiotropic effects on atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease [11–14]. We and other groups have demonstrated the expression of PPARs within symptomatic advanced atherosclerosis and identified them as potential drug targets [15–17]. The purpose of this study was to investigate the ability of PPAR- α and -γ ligands to acutely modify TM expression in unstable human atheromas.

Materials and Methods

Patients

This study was approved by the local ethics committees and informed consent was obtained from participating patients. Entry criteria were: a) a transient ischaemic attack (TIA) or stroke ≤6 weeks prior to carotid endarterectomy, b) internal or common carotid stenosis >70% defined by velocity criteria on duplex as previously described [18]. Exclusion criteria included: a) patients with amaurosis fugax alone, non-focal, atypical or distant neurological symptoms, b) asymptomatic patients, c) patients not receiving a Statin or anti-platelet medication. Clinical, imaging and serum characteristics of the patients were prospectively measured and recorded as previously described [19, 20].

Specimens

A conventional endarterectomy was performed and specimens were immediately placed in cold culture medium and brought to the laboratory for experimental work [19]. Specimens were dissected into the proximal internal carotid (PIC) and common carotid (CC) endarterectomy sites for primary assessment by immunohistochemistry (4 patients, 4 biopsies) or explant culture (20 patients for each drug treatment; 10 assessed by Western blotting and 10 for TM activity).

Explant culture

Explant cultures were carried out in vitro as previously described [15, 19]. Briefly, paired biopsies from the macroscopically diseased portion of both the PIC and CC were placed in tissue culture wells, intima up, in 1 ml of medium and incubated at 37°C/5% CO2. Biopsies were stabilized in culture for 24 hours prior to replacement of culture media with or without PPAR- α or -γ ligand. Thus one sample from each site was incubated in the presence of a PPAR α (fenofibrate 10µM) or a PPARγ (rosiglitazone 4.2µM) ligand, while the other acted as a control. The culture medium was replaced every 48 hours. After 5 days in culture, explants were stored at −80°C for later assessment of TM expression or activity.

Cell culture

Human aortic endothelial cells (HAEC) (Cambrex Bio Science Australia) were cultured to sub-confluence at 37°C/5% CO2 in EGM-2 culture media (Cambrex Bio Science Australia). For experiments cells were passaged with trypsin-versene to 24-well plates (104 cells/well). HAEC purity was confirmed by the typical ‘cobblestone’ morphology of endothelial cells and by immunohistochemistry showing positive staining for Von Willebrand Factor and CD31 and negative staining for smooth-muscle α-actin. Cells were used between passages 3 to 5. TM is constitutively expressed by resting endothelial cells. In order to assess the effect of PPAR medication on TM expression, preliminary time course and dose-response studies with tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α were carried out to determine an optimal treatment time and dose. These experiments showed that incubating endothelial cells with 100U/mL of TNF-α for 24 hours resulted in a 40–70% reduction in the surface expression of TM. These parameters were chosen to assess the effect of PPAR ligands on surface TM, as they permitted the detection of an increase or decrease in TM expression.

Oxidation of Low density Lipoprotein

Low density lipoprotein was oxidized as previously described [21]. Briefly LDL (Calbiochem, Merk Pty Ltd) was resuspended to a final concentration of 2mg/mL in PBS and 2µM CuSO4. The solution was irradiated by UV light (254 nm, 0.65 mW/cm2) for 12 hours at 4°C (UVGL-15 compact UV lamp, UVP). Oxidation was confirmed by a 3-fold increase of absorbance at 234nm, as previously observed [21].

Flow cytometry

Following culture with medication or carrier control (DMSO), HAECs were collected in wash buffer [PBS/BSA(0.1%)/sodium azide (0.1%)], and incubated on ice with a monoclonal antibody to TM (DakoCytomation, 1009, 2.5µg/ml) or IgG negative control (Dako, DAKG01, 2.5µg/ml) for 30 minutes, washed and incubated a further 30 minutes with a secondary FITC-labeled anti-mouse IgG (Dako, F0479, 20µg/ml) prior to fluorescence-activated cell scanning (FACS). The cell-associated fluorescence of 10 000 events per sample was analysed in a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) using the Cell Quest software. Cells showing positive staining for propidium iodide were excluded from analysis by gating. TM expression was quantified by measuring the mean fluorescence intensity (MFLI) in the FL-1 channel. The MFLI of each sample was expressed as a percent of MFLI of the control sample (untreated cells) to allow statistical analysis across multiple experiments.

Immunohistochemistry

Serial cryostat sections (5µm) of biopsies taken from the PIC were exposed to antibodies directed against the endothelial cell marker CD31 (JC70A, 4.5µg/mL, Dakocytomation) and TM (24FM, 1µg/mL, Serbio, France) and developed using the Envision immunoperoxidase system (DakoCytomation) [15, 19].

Western blotting

Western blotting was used to quantify TM (D-3, 4.5□g/mL, SantaCruz Biotechnology) in carotid explants cultured with and without a PPAR- α or -γ ligand. Tissue samples were ground under liquid nitrogen and total protein extracted and quantified using the Bradford method (Coomassie Brilliant Blue G250 dye, Biorad). 30µg of total protein was loaded into each lane. In preliminary studies we found that for these endarterectomy samples careful loading of pre-assessed protein amounts was a better measure of consistent loading than probing gels with control antibodies such as those raised against actin or tubulin [15,19]. Treated and control samples from each patient were always run on the same membrane to ensure comparable exposure conditions. Blots were developed with chemiluminescence (ECL advance, Amersham) and digitally captured (Bio-Rad, Chemidoc XRS) and analyzed (Bio-Rad, Quantity One). Densitometry was used to quantify bands representing TM which were recognized at 105kD molecular weight as previously described [22]. Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of adjusted band density units and also expressed as the proportional fold change compared between treated and non-treated biopsies of atheroma.

Thrombomdulin activity assay

Cryopreserved tissue was thawed, rinsed in chilled buffer (20mM Tris pH7.4, 0.1M NaCl, 1mM CaCl2) and homogenised under liquid nitrogen. The ground tissue was washed three times in the rinse buffer (to remove exogenous clotting factors) prior to incubation with 5mg/mL human serum albumin, 5µg/mL Protein C (Enzyme research laboratories) and 0.1µg/mL thrombin (Enzyme research laboratories) at 37°C with shaking for 2hrs. To stop the reaction, 0.1mg/mL anti-thrombin III (Enzyme research laboratories) and 25U/mL heparin was added. Activated Protein C activity (APC) was measured by adding 100µL of chromogenic substrate S2366 (1.5mM, Chromogenix) in 100mM CsCl and 30mM Tris pH 7.4. The hydrolysis of the substrate was followed at 5 second intervals at 405nm in a microplate reader (Sunrise Tecan plate reader), and activity reported as change in absorbance/ min, as previously described [23, 24], normalized to total protein extracted from the sample after the activity assay. For every assay run a thrombin alone control was included. The activity level for this reaction was always much lower than that of the samples and all values presented have had the residual thrombin activity removed. Standard curves using commercially available APC were used to determine how much APC was generated in the activity assays. A change of 0.2 absorbance units/min was generated by 0.19±0.004mg APC (data not shown). Given the range of doses of medications and the variety of different culture conditions examined it was not feasible to carry out detailed activity assays in cultured endothelial cells.

Data analysis

The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare TM expression and activity in explants that were treated and non-treated with PPAR- α and -γ ligands. Results were presented as mean ± standard error of both density units and relative ratios. For the assessment of medication on TM surface expression by endothelial cells, data was compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test.

Results

Effect of PPAR ligands on TM expression by HAECs in vitro

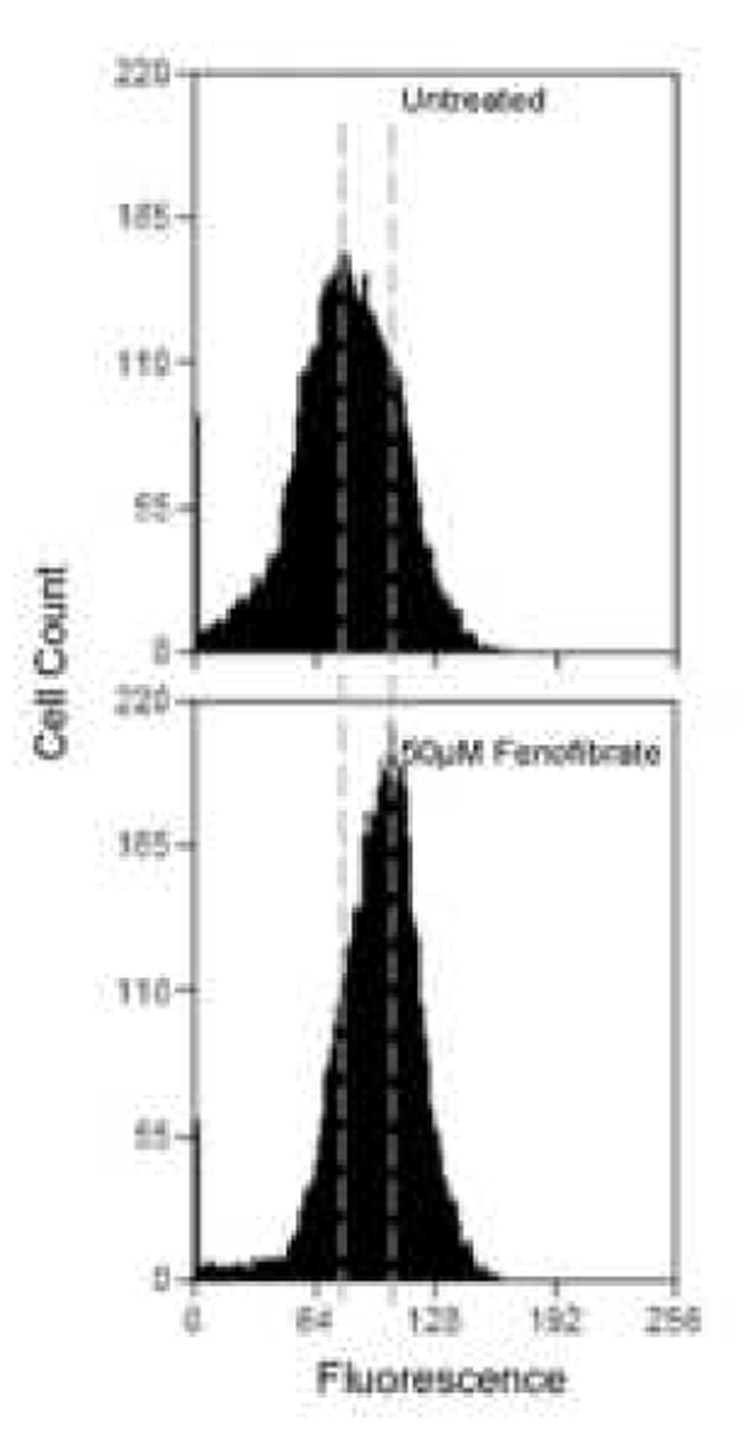

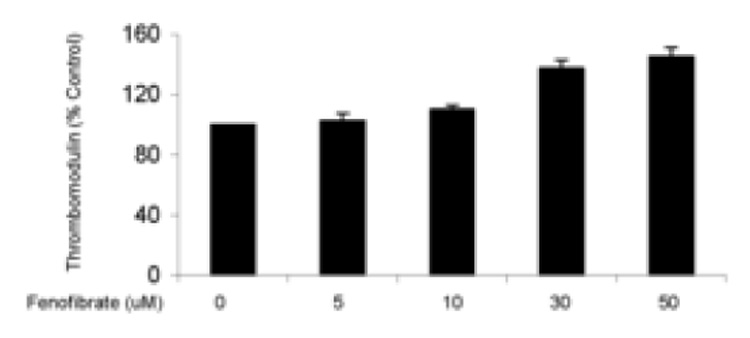

The HAECs constitutively expressed surface TM. Fenofibrate and rosiglitazone dose-dependently increased and decreased TM expression respectively (Figure 1). While we only carried out limited activity assays in cultured cells, we found that in the presence of 10µM fenofibrate TM activity reduced to 62±5% of that measured in cells cultured with vehicle control (n=6, p<0.05).

Figure 1.

Endothelial surface thrombomodulin expression assessed by flow cytometry. (a) Representative histograms show a change in TM expression when cells are exposed to 50µM fenofibrate. The increase in mean fluorescence can be seen by the overall shift of the curve to the right. Overall results from treating cells with increasing concentrations of fenofibrate (b) or rosiglitazone (c) for 24 hours are shown as bar charts. Results are expressed as a % of untreated cells ± standard error. N=3, p<0.05.

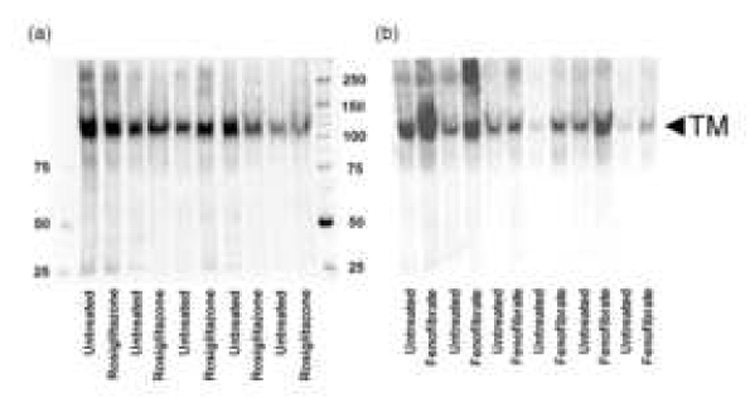

Effect of PPAR ligands on TM expression and activity by carotid atheroma explants

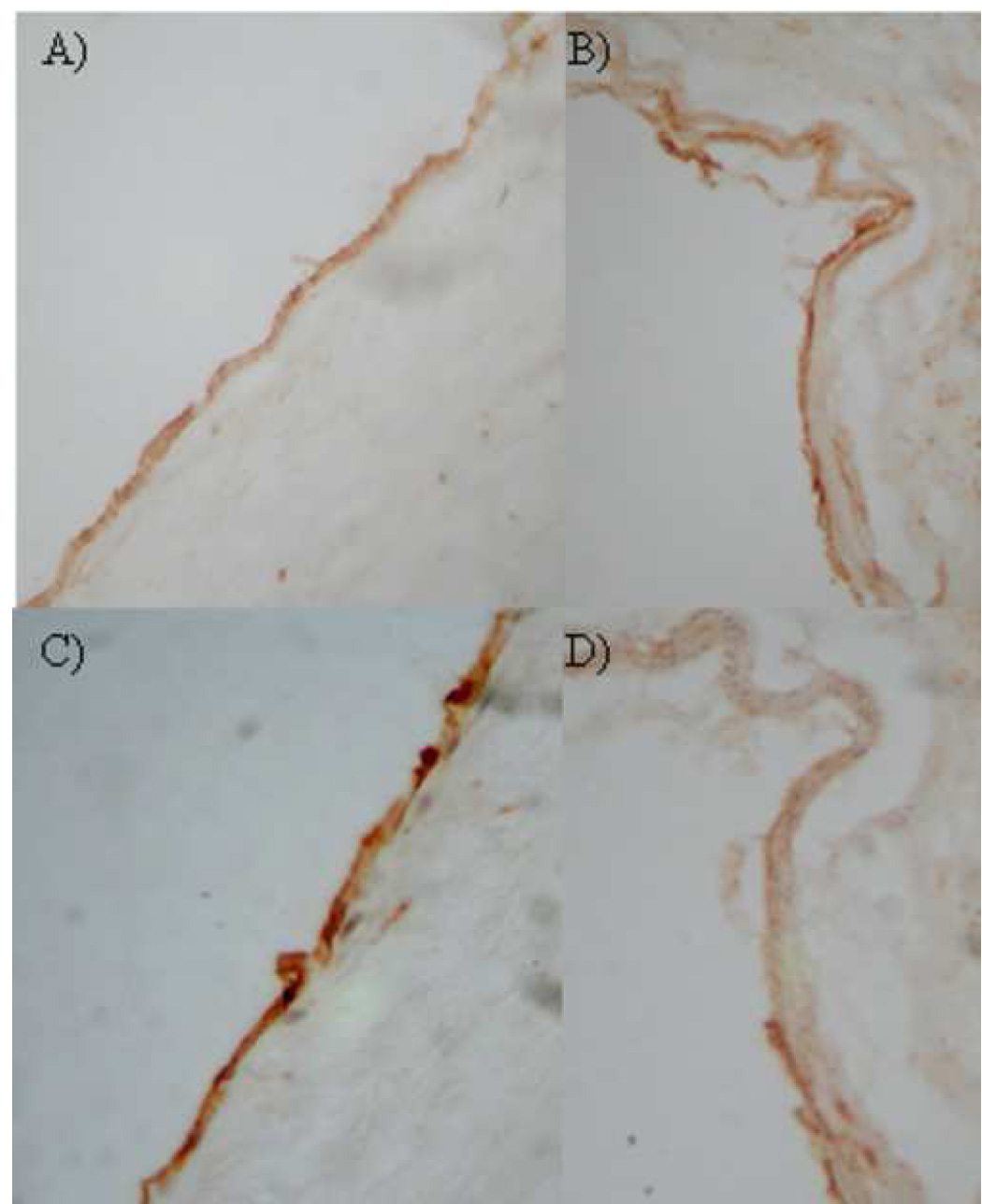

TM expression was demonstrated within the endothelium of unstable carotid atheromas using immunohistochemistry (Figure 2). Reduced expression of TM was noted at the shoulder of the atherosclerotic plaques (Figure 2d). We assessed the effect of PPAR ligands on the expression and activity of TM in carotid atheromas using Western blotting and activity assays. Incubation of atheroma biopsies with PPAR ligands led to changes in TM seen to vary substantially from one sample to another. In the first 10 samples assessed, the mean relative atheroma TM concentration increased by 1.7 fold (p<0.001) following incubation with fenofibrate for 4 days, with high standard errors noted (Table 1, Figure 3). However, in a further experiment in which TM activity was assessed, no effect of fenofibrate was observed (Table 1). Similar disparity in the effect of medication on expression and activity was demonstrated for rosiglitazone. Rosiglitazone has no significant effect on TM concentration but reduced activity to 73% of the control (p<0.01) (Table 1, Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Representative photomicrographs of atherosclerotic carotid plaque. Shown are x40 magnification photomicrographs of immunostaining for CD31 (a and b) and TM (c and d). Expression of TM was reduced towards the shoulder of the plaque (iv).

Table I.

Effect of fenofibrate and rosiglitazone on the expression and activity of TM in symptomatic carotid atheromas.

| Rosiglitazone | Fenofibrate | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio | Ratio | |||||||

| Control | Treatment | Control | Treatment | Control | Treatment | Control | Treatment | |

| Thrombomodulin Expression | ||||||||

| Western Blot (adjusted band density units) | ||||||||

| 60 ±44 | 67 ±36 | 1.26 | 41 ±25 | 55 ±36* | 1.69 ±1.21* | |||

| 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||||

| ±0.60 | ||||||||

| Activity Rate (absorbance change/ min/ mg protein) | ||||||||

| 0.20 | 0.13 | 0.72 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 1.0 | 1.01 | ||

| 1.0 | ||||||||

| ±0.16 | ±0.08* | ±0.38* | ±0.19 | ±0.22 | ±0.48 | |||

Shown are the adjusted band density units and activity rates (actual values and ratios) for paired atheroma samples exposed to rosiglitazone or fenofibrate (treatment) or incubated alone (control) for 4 days. Samples to be compared were included in the sample blot for equivalent conditions (Figure 3). All results are mean± standard error for 10 paired samples.

p<0.01.

Figure 3.

Western blots showing assessment of TM in paired treatment and control carotid atheroma biopsies from patients with recent symptoms. a) Paired biopsies incubated with or without rosiglitazone and b) paired biopsies incubated with or without fenofibrate. Also shown are molecular weight markers.

Effect of PPAR ligands on TM expression by HAECs cultured in a pro-atherosclerotic environment

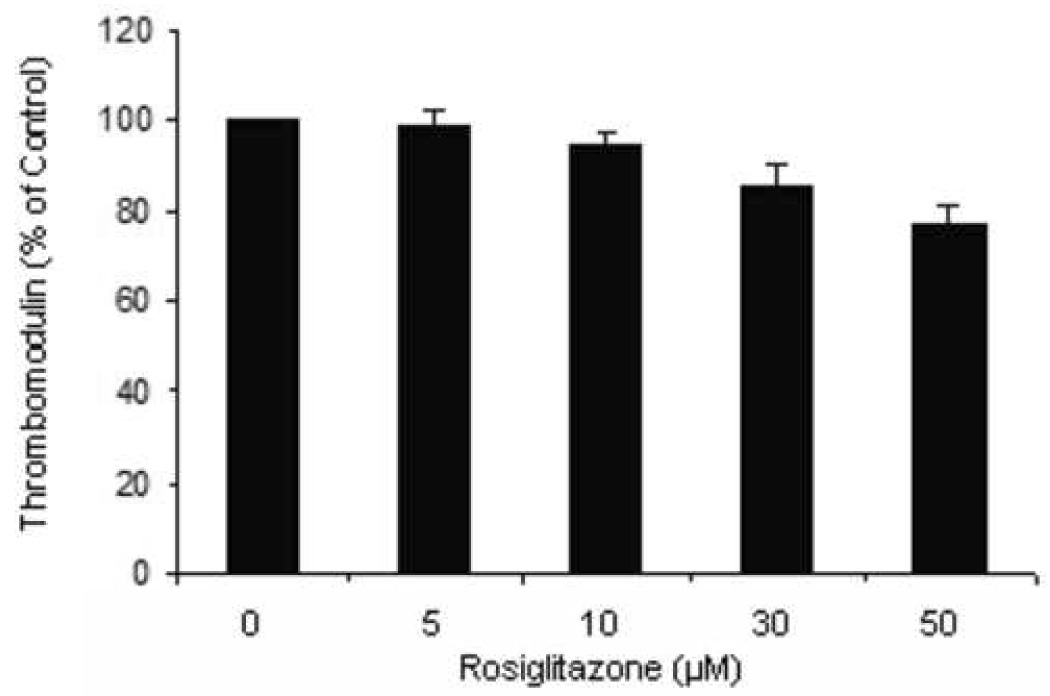

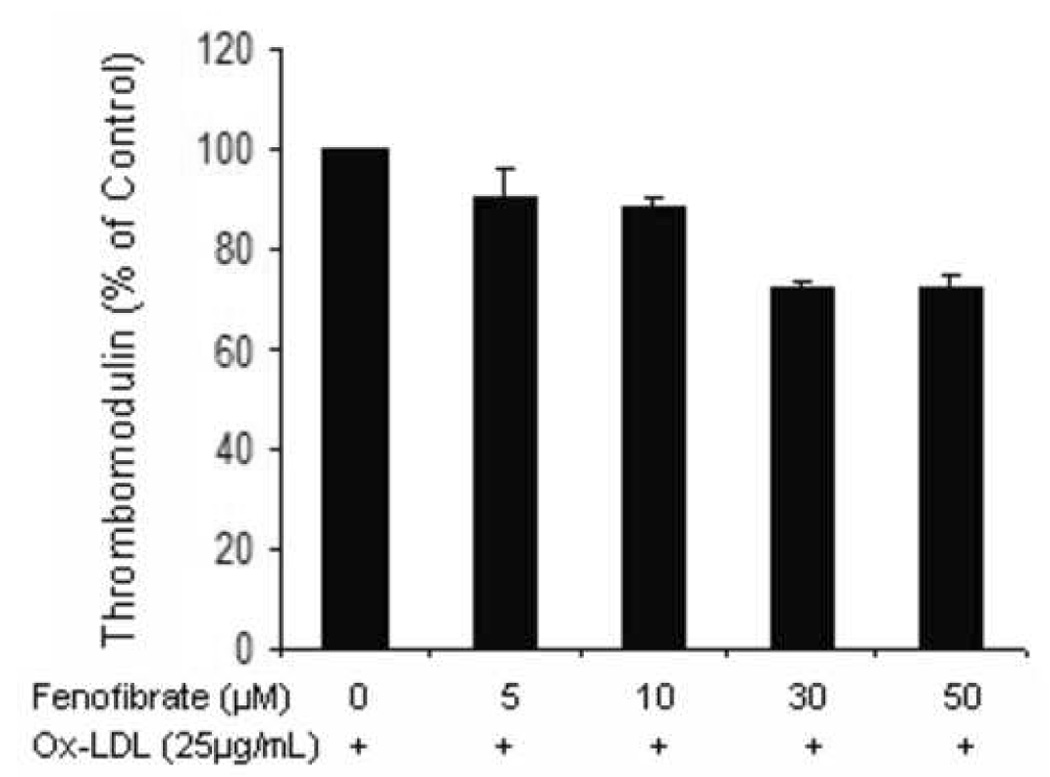

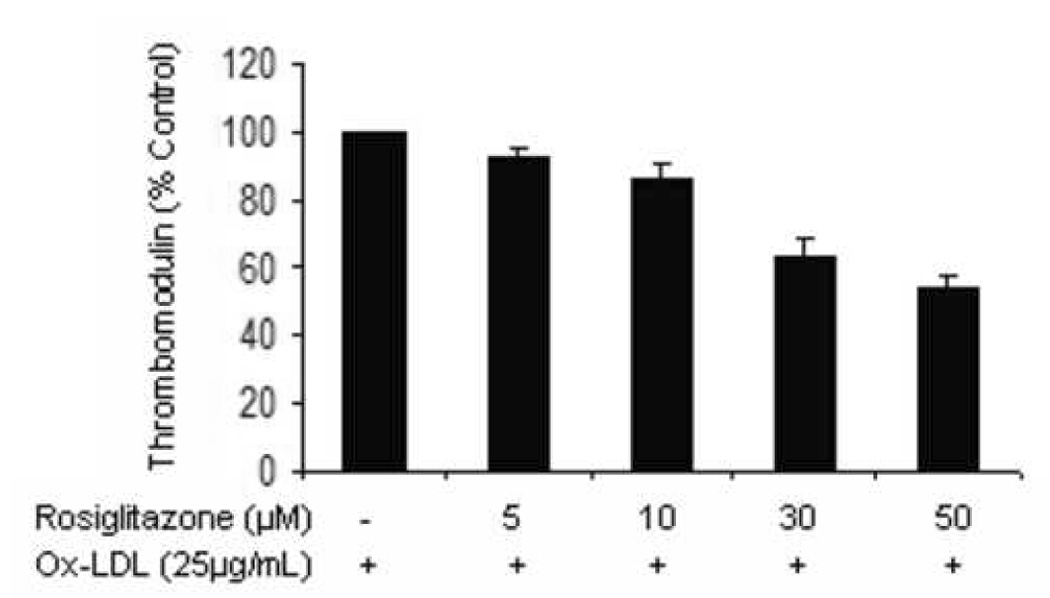

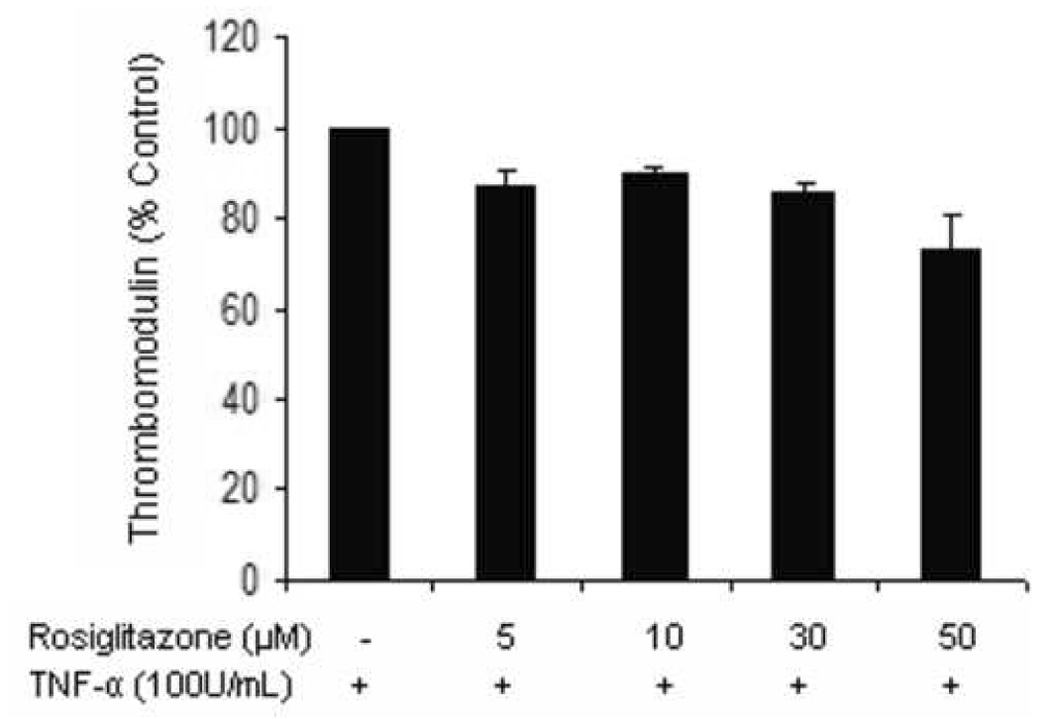

In order to further investigate the sample to sample variation in the effects of PPAR ligands on TM expression by carotid explants, we assessed the effect of PPAR ligands on HAEC TM surface expression in the presence of factors previously demonstrated within atheroma, including TNF-α and oxidized LDL. In the presence of TNF-α (100U/mL), fenofibrate had no significant effect on HAEC surface TM expression (100.0, 99.2, 96.5, 121.8, 130.3 % of control TM expression when treated with 0, 5, 10, 30, 50 µM fenofibrate, respectively, p=0.057). In the presence of oxidized LDL, fenofibrate dose-dependently reduced TM expression (Figure 4). The effect of rosiglitazone to downregulate HAEC TM expression was more pronounced in the presence of oxidized LDL than TNF-α (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Aortic endothelial cells incubated with ox-LDL (25µg/mL) in the presence of increasing concentrations of fenofibrate for 24 hrs were assessed for surface TM expression by flow cytometry. The experiment was carried out on 3 separate occasions in triplicate. Results are expressed as a % of untreated cells ± standard error. P<0.05.

Figure 5.

Aortic endothelial cells incubated with ox-LDL (25µg/mL, a) or TNF-α (100U/mL, b) in the presence of increasing concentrations of rosiglitazone for 24 hrs were assessed for surface TM expression by flow cytometry. The experiments were carried out on 3 separate occasions in triplicate. Results are expressed as a % of untreated cells ± standard error. P<0.05.

Discussion

Symptomatic atherosclerotic lesions are associated with a high risk of subsequent events compared to asymptomatic ones [9]. Medical stabilisation of such plaques would help reduce fatal events and lower the number of surgical interventions required. The present study investigated the potential of the PPAR ligands, rosiglitazone and fenofibrate, to modify TM expression and activity. Our findings suggest a possible role for the PPAR-α ligand, fenofibrate in acutely up-regulating TM levels within the endothelium of unstable atheromas. We and other investigators have previously demonstrated the ability of PPAR ligands to favourably modify tissue factor expression in atherosclerotic tissue [15, 25–28]. Using similar study design we recently demonstrated that both fenofibrate and rosiglitazone reduced tissue factor expression and activity in recently symptomatic carotid atheromas in vitro [15].

TM expression plays a key role in determining vessel thrombogenicity. Analysis of aortic atherosclerotic lesions has shown many cells types other than endothelial cells to express TM [29], however we failed to detect TM in smooth muscle cells, monocytes or macrophages within carotid atheromas. TM was expressed within intimal endothelial cells (Figure 1). Furthermore, although many studies report the expression of PPAR isotypes as being cell or tissue type specific, PPAR-α and –γ are both expressed by endothelial cells [30]. Our previous studies demonstrate minimal tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) activity in unstable carotid atheroma [15]. These data suggest that endothelial TM should be the primary target in strategies aimed at improving the anticoagulant capacity of unstable atheroma. For these reasons we studied the expression of TM by endothelial cells in response to PPAR ligands in vitro.

Initial experiments incubating endothelial cells with the PPAR-α ligand fenofibrate for 24 hours dose-dependently increased TM expression (Figure 1). In contrast the PPAR-γ ligand, rosiglitazone, reduced HAEC surface TM levels (Figure 1). These findings suggested a potential favourable effect of fenofibrate in unstable atheromas. We investigated these findings further in carotid atheroma samples incubated with medication for 4 days in vitro, using protocols we had previously found to be reproducible [15,19]. We similarly demonstrated the ability of fenofibrate to upregulate expression of TM but demonstrated no effect of rosiglitazone (Table I, Figure 3). We did however note significant variation in response from carotid atheroma samples from different patients which was greater than we had previously experience with tissue factor. In addition the findings from activity assays performed on a different sub-group of samples gave different findings. These studies failed to demonstrate the ability of fenofibrate to upregulate TM activity (Table I).

There are a number of possible reasons for the disparity between the findings of our TM expression and activity assays in carotid atheroma samples. Firstly, in order to assess TM activity we utilized homogenized atheroma biopsies which had been incubated with or without medication. We did not extract total cellular protein from the samples until after the activity assays (in order to normalize the assay results). We used this approach since utilizing total protein prior to the assay may have interfered with the activity assessment.

We also reasoned that the whole atheroma would give a more realistic assessment of the situation in patients. In contrast for Western blotting total protein extraction was required prior to TM estimation by antibody recognition. These different methods of assessment can thus be expected to disagree. In a previous study for example we demonstrated expression of TFPI protein in carotid atheroma samples but were unable to identify any TFPI activity [15]. We did find concordance between the protein expression and activity findings for tissue factor in the same study however [15]. In view of this and the fact that the findings varied from one patient to another we carried out further cell culture studies.

It has been demonstrated in a large number of randomized trials that the effect of medications vary from one patient to another. In this study we have identified one of the mechanisms that may underlie this variation in response. We found that HAEC expression of TM was consistently up-regulated by fenofibrate, however in the presence of TNF-α or oxidized LDL these effects were altered. In particular when HAECs were incubated with fenofibrate in the presence of oxidized LDL the effect of the medication was reversed (Figure 1 and Figure 4). While it is impossible to replicate the atheromatous environment in vitro, both TNF-α and oxidized LDL have been demonstrated within atherosclerosis and shown to modulate TM expression, supporting the relevance of these studies [31–35]. There are a number of other mechanisms which may account for the inter-sample variation in response to PPAR ligand incubation in this study. We used macroscopically similar biopsies taken from adjacent sites of carotid atheroma as treatment and control pairs for our explant studies. In a previous study we demonstrated that there was little variation in thrombogenicity of these paired biopsies and also demonstrated consistent changes with tissue factor [15]. However, part of the variability in findings from different samples may result from the heterogenity of atheroma.

Our results demonstrate that the PPAR-α ligand fenofibrate increase endothelial TM expression. This finding suggests the potential value of fenofibrate in patients with unstable atheroma. However, the effects of fenofibrate in vivo will likely vary from one atherosclerotic plaque to another due to the differing environments present. The development of imaging techniques or biomarkers which can quantify the characteristics of atheroma, such as TNF or oxidized LDL levels, in different patients may ultimately assist in better targeting of therapies.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by funding from the National Heart Foundation, Australia and the NIH (R01 HL080010-01), USA. JG is a Practitioner Fellow of the NHMRC, Australia (431503). The funding source had no role in the design of the study or analysis of the results.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Weiler H, Isermann BH. Thrombomodulin. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:1515–1524. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seigneur M, Dufourcq P, Conri C, Constans J, Mercie P, Pruvost A, Amiral J, Midy D, Baste J, Boisseau MR. Levels of plasma thrombomodulin are increased in atheromatous arterial disease. Thromb Res. 1993;71:423–431. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(93)90116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerdes VEA, Kremer Hovinga JA, ten Cate H, Brandjes DPM, Buller HR. Soluble thrombomodulin in patients with established atherosclerosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:200–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.0562f.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu KK, Aleksic N, Ballantyne CM, Ahn C, Juneja H, Boerwinkle E. Interaction between soluble thrombomodulin and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in predicting risk of coronary heart disease. Circulation. 2003;107:1729–1732. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000064894.97094.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suzuki K, Stenflo J, Dahlback B, Teodorsson B. Inactivationof human coagulation factor V by activated protein C. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:1914–1920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiseil W, Canfield W, Ericsson LH, Davie EW. Anticoagulant properties of bovine plasma protein C following activation by thrombin. Biochemistry. 1977;16:5824–5830. doi: 10.1021/bi00645a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laszik ZG, Zhou XJ, Ferrell GL, Silva FG, Esmon CT. Down-regulation of endothelial expression of endothelial cell protein C receptor and thrombomodulin in coronary atherosclerosis. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:797–802. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61753-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seigneur M, Dufourcq P, Conri C, Constans J, Mercie P, Pruvost A, Amiral j, Midy D, Baste J, Boisseau MR. Levels of plasma thrombomodulin are increased in atheromatous arterial disease. Thromb Res. 1993;71:423–431. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(93)90116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golledge J, Greenhalgh RM, Davies AH. The symptomatic carotid plaque. Stroke. 2000;31:771–781. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.3.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duval c, Chinetti G, Trottein F, Fruchart J, Staels B. The role of PPARs in atherosclerosis. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8:422–430. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(02)02385-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mukherjee R, Davies PJ, Crombie DL, Bischoll ED, Cesario RM, Jow L, Hamann LG, Boehm Mf, Mondon CE, Nadzan AM, Paterniti JR, Heyman RA. Sensitization of diabetic and obese mice to insulin by retinoid X receptor agonists. Nature. 1997;386:407–410. doi: 10.1038/386407a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klappacher GW, Glass CK. Roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ in lipid homeostasis and inflammatory responses of macrophages. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2002;13:305–312. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200206000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halabi CM, Sigmund CD. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ and its agonists in hypertension and atherosclerosis. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2005;5:389–398. doi: 10.2165/00129784-200505060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsueh WA, Bruemmer D. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ: implications for cardiovascular disease. Hypertension. 2004;43:297–305. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000113626.76571.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Golledge J, Mangan S, Clancy P. Effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor ligands in modulating tissue factor and tissue factor pathway inhibitor in acutely symptomatic carotid atheromas. Stroke. 2007;38:1501–1508. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.474791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehrabi MR, Haslmayer P, Humpeler S, Strauss-Blasche G, Marktl W, Tamaddon F, Serbecic N, Wieselthaler G, Thalhammer T, Glogar HD, Ekmekcioglu C. Quantitative analysis of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) expression in arteries and hearts of patients with ischaemic or dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail. 2003;5:733–739. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(03)00148-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Legedz L, Vidal H, Loizon e, Feugier P, Bricca G. Peroxysome proliferator-activated receptors' gene expression in type 2 diabetic atheroma. Eur J Clin Invest. 2004;34:634–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2004.01397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Golledge J, Ellis M, Sabharwal T, Sikdar T, Davies AH, Greenhalgh RM. Selection of patients for carotid endarterectomy. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30:122–130. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(99)70184-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golledge J, McCann M, Mangan S, Lam A, Karan M. Osteoprotegerin and osteopontin are expressed at high concentrations within symptomatic carotid atherosclerosis. Stroke. 2004;35:1636–1641. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000129790.00318.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes melitius. Diabetes care. 2006;29 (Suppl 1):S43–S48. [PubMed]

- 21.Krisko A, Kveder M, Pifat G. Effect of caffeine on oxidation susceptibility of human plasma low density lipoprotiens. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2005;355:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki K, Kusumoto H, Deyashiki Y, Nishioka J, Maruyama I, Zushi M, Kawahara S, Hinda G, Yamamoto S, Horiguchi S. Structure and expression of human thrombomodulin, a thrombin receptor on endothelium acting as a cofactor for protein C activation. The EMBO J. 1987;6:1891–1897. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02448.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang HC, Shi GY, Jiang SJ, Shi CS, Wu CM, Yang HY, Wu HL. Thrombomodulin-mediated cell adhesion: involvement of its lectin-like domain. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46750–46759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305216200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gosling M, Golledge J, Turner RJ, Powell JT. Arterial flow conditions downregulate thrombomodulin on saphenous vein endothelium. Circulation. 1999;99:1047–1053. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.8.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neve BP, Corseaux D, Chinetti G, Zawadzki C, Fruchart J, Duriez P, Staels B, Jude B. PPARα agonits inhibit tissue factor expression in human monocytes and macrophages. Circulation. 2001;103:207–212. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marx N, Mackman N, Schonbeck U, Yilmaz N, Hombach V, Libby P, Plutzky J. PPARα activators inhibit tissue factor expression and activity in human monocytes. Circulation. 2001;103:213–219. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eligini S, Banfi C, Brambilla M, Camera M, Barbier SS, Poma F, Tremoli E, Colli S. 15-deoxy-12,14- prostaglandin J2 inhibits tissue factor expression in human macrophages and endothelial cells: evidence for ERK1/2 signaling pathway blockade. Thromb Haemost. 2002;88:524–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanehara H, Tohda G, Oida K, Suzuki J, Ishii H, Miyamori I. Thrombomoduline expressoin by THP-1 but not vascular cells is upregulated by pioglitazone. Thromb Res. 2003;108:227–234. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(03)00056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tohda G, Oida K, Okada Y, Kosaka S, Okada E, Takahashi S, Ishii H, Miyamori I. Expression of thrombomodulin in atherosclerotic lesions and mitogenic activity of recombinant thrombomodulin in vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:1861–1869. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.12.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inoue I, Shino K, Noji S, Awata T, Katayama S. Expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) in primary cultures of human vascular endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;246:370–374. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeGraba TJ. Expression of inflammatory mediators and adhesion molecules in human atherosclerotic plaque. Neurology. 1997;49:S15–S19. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.5_suppl_4.s15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skoog T, Dichtl W, Boquist S, Skoglund-Andersson C, Karpe F, Tang R, Bond MG, de Faire U, Nilsson J, Eriksson P, Hamsten A. Plasma tumour necrosis factor-α and early carotid atherosclerosis in healthy middle-aged men. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:376–383. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu M, Ylitalo K, Salonen R, Salonen JT, Taskinen M. Circulating oxidized low-density lipoportein and its association with carotid intima-media thickness in asymptomatic members of familial combined hyperlipidemia families. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1492–1497. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000135982.60383.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nan B, Lin P, Lumsden AB, Yao Q, Chen C. Effects of TNF-a and curcumin on the expression of thrombomdulin and endothelial protein C receptor in human endothelial cells. Thromb Res. 2005;115:417–426. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishii H, Tezuka T, Ishikawa H, Takada K, Oida K, Horie S. Oxidized phospholipids in oxidized low-density lipoprotein down-regulate thrombomodulin transcription in vascular endothelial cells through a decrease in the bindng of RARβ-RXRα heterodimers and Sp1 and Sp3 to their binding sequences in the TM promoter. Blood. 2003;101:4765–4774. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]