Abstract

The nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) is a key regulator of adipocyte differentiation in vivo and ex vivo and has been shown to control the expression of several adipocyte-specific genes. In this study, we used chromatin immunoprecipitation combined with deep sequencing to generate genome-wide maps of PPARγ and retinoid X receptor (RXR)-binding sites, and RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) occupancy at very high resolution throughout adipocyte differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells. We identify >5000 high-confidence shared PPARγ:RXR-binding sites in adipocytes and show that during early stages of differentiation, many of these are preoccupied by non-PPARγ RXR-heterodimers. Different temporal and compositional patterns of occupancy are observed. In addition, we detect co-occupancy with members of the C/EBP family. Analysis of RNAPII occupancy uncovers distinct clusters of similarly regulated genes of different biological processes. PPARγ:RXR binding is associated with the majority of induced genes, and sites are particularly abundant in the vicinity of genes involved in lipid and glucose metabolism. Our analyses represent the first genome-wide map of PPARγ:RXR target sites and changes in RNAPII occupancy throughout adipocyte differentiation and indicate that a hitherto unrecognized high number of adipocyte genes of distinctly regulated pathways are directly activated by PPARγ:RXR.

Keywords: Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor, nuclear receptor, ChIP-seq, adipocyte differentiation

Adipogenesis is one of the best characterized differentiation processes. Several preadipocyte cell culture models have been developed and used to carefully dissect the sequence of molecular events governing the adipogenic process. Among these adipogenic cell lines, the murine 3T3-L1 preadipocyte cell line (Green and Kehinde 1974) represents one of the best characterized models. Upon addition of adipogenic inducers, including glucocorticoids, cAMP elevating agents, and insulin/insulin-like growth factor, these cells undergo one to two rounds of mitotic clonal expansion followed by growth arrest and terminal differentiation. Several gain- and loss-of-function experiments have revealed an intricate interplay of activating and inhibitory signals involved in the regulation of the adipogenic process (MacDougald and Mandrup 2002; Rosen and MacDougald 2006).

The nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ; NR1C3) is an obligatory key regulator of adipocyte differentiation in vivo as well as ex vivo (Farmer 2006). In addition, PPARγ acts as a transcriptional activator of many adipocyte-specific genes involved in lipid synthesis, handling and storage of lipids, growth regulation, insulin signaling, and adipokine production (Lehrke and Lazar 2005). PPARγ is also necessary for maintenance of the adipocyte phenotype and for survival of adipocytes in white adipose tissue in vivo (Imai et al. 2004). PPARγ binds to peroxisome proliferator response elements (PPREs) as a heterodimer with members of the retinoid X receptor (RXR; NR2B) nuclear receptor subfamily. The PPREs characterized are primarily of the DR1 type (Palmer et al. 1995).

PPARγ can be activated by polyunsaturated fatty acids and fatty acid derivatives (Kliewer et al. 1997; Nagy et al. 1998); however, the nature of the physiologically relevant agonists has remained elusive. Interestingly, during adipocyte differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells, there is a boost in the synthesis of endogenous PPARγ agonists around day 2 (Madsen et al. 2003; Tzameli et al. 2004), which appears to be important for triggering the adipogenic conversion.

PPARγ exists as two isoforms—PPARγ2, which is highly adipocyte-specific, and PPARγ1, which is more widely expressed in different cell types. The level of both PPARγ isoforms, but PPARγ2 in particular, is low in preadipocytes and strongly induced early in the differentiation process. Members of the transcription factor family CAAT/enhancer-binding proteins (C/EBPs) are known to activate expression from the PPARγ2 promoter (Clarke et al. 1997).

In this study, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) combined with deep sequencing (ChIP-seq) to map all binding sites of PPARγ and RXR during adipocyte differentiation. Furthermore, we performed parallel RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) ChIP-seq throughout differentiation. These analyses provide a comprehensive and high-resolution genome-wide map of PPARγ:RXR target sites during the conversion of preadipocytes to mature adipocytes. The coupling with RNAPII occupancy enables us to relate PPARγ: RXR binding to transcriptional events at close-by genes and furthermore provides the first genome-wide map of RNAPII occupancy during a differentiation process.

Results

Genome-wide mapping of PPARγ- and RXR-binding sites during adipocyte differentiation

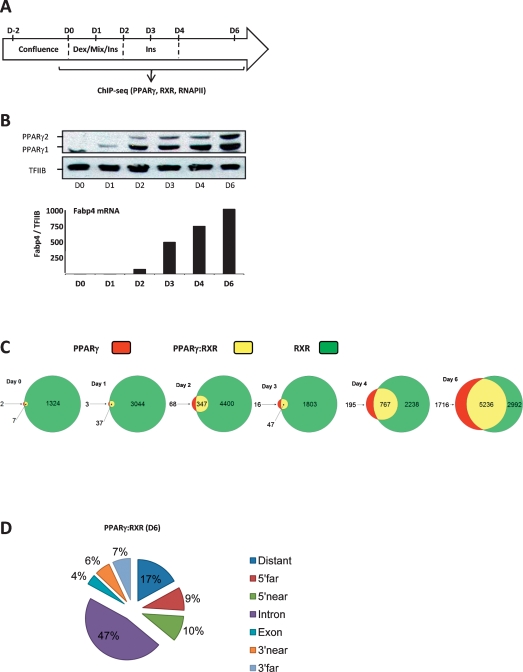

Cultures of the 3T3-L1 preadipocyte cell line are induced to differentiate in a highly synchronous manner by subjecting 2-d post-confluent cells to a cocktail of adipogenic inducers (Fig. 1A). The cells subsequently undergo mitotic clonal expansion, followed by growth arrest, induction of adipocyte gene expression, and accumulation of lipid droplets. The percentage of differentiated cells, as assessed by lipid-filled cells, is routinely on the order of 95%. The induction of PPARγ expression represents an early key event in the differentiation process and is followed by a major wave of induction of adipocyte-specific genes like the adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein (Fabp4) (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Genome-wide mapping of PPARγ:RXR-binding sites during adipocyte differentiation. (A) Experimental outline. Adipocyte differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells was induced by exposing two post-confluent cells to standard DMI procedure. Cells were harvested at days 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 for mRNA, protein, and chromatin preparation. (B) Expression of PPARγ by Western blotting and mRNA levels of the target gene Fabp4 during adipogenesis. RNA levels were determined by real-time PCR and normalized to TFIIB, and the day 0 level was set to 1. (C) The number of PPARγ- and RXR-binding sites detected by ChIP-seq during adipogenesis. Peaks were called using FindPeak (<0.001 FDR). Results are shown as Venn diagrams representing the number of target sites during differentiation for PPARγ only (red), RXR only (green), and shared PPARγ:RXR (yellow). Circle sizes are representative of the number of binding sites on a given day. (D) Genomic position of shared PPARγ:RXR-binding sites on day 6. Binding sites were divided into the following categories based on their position relative to the nearest gene (PinkThing): distant (>25 kb), 5′ far (25–5 kb), 5′ near (5–0 kb), intragenic, intronic, intragenic, exon, 3′ near (0–5 kb), and 3′ far (5–25 kb).

To obtain a temporal genome-wide map of PPARγ: RXR target sites during adipocyte differentiation, we sampled chromatin throughout differentiation (days 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6) and subjected that to high-resolution ChIP-seq analysis using antibodies specific for PPARγ and RXR, respectively. Following initial testing of chromatin quality and the ChIP efficiency by ChIP-PCR (data not shown), we submitted the ChIPed DNA to deep sequencing (Supplemental Table S1).

From these ChIP-seq analyses, we generated genome-wide high-resolution maps of PPARγ- and RXR-binding sites (FDR level <0.001). The total number of mapped sequence tags for the different days of differentiation was equalized relative to the day with the lowest number of mapped tags. The Venn diagrams in Figure 1C illustrate the number of binding sites for PPARγ and RXR at the different days. The highest number of sites is observed at day 6, where a total of 6952 and 8228 target sites for PPARγ and RXR, respectively, can be identified. Among these are 5236 shared target sites, which represent 75% and 64% of all identified PPARγ- and RXR-binding sites on day 6, respectively. ChIP-PCR on a different biological replica showed that 30 out of 31 randomly picked shared binding sites of variable peak intensity could be validated (Supplemental Fig. S1). Four of the eight reporter constructs containing cloned PPARγ:RXR-binding regions were responsive to PPARγ transactivation in NIH-3T3 fibroblasts (Supplemental Fig. S2).

In keeping with the very low levels of PPARγ at day 0, only nine PPARγ target sites were detected at this day. The number remains low at day 1; however, at day 2, there is a significant increase in the number of detectable PPARγ target sites to 415. This increase coincides with the significant increase in PPARγ1 and PPARγ2 expression (Fig. 1B) and with the reported boost in endogenous agonist production (Madsen et al. 2003; Tzameli et al. 2004). At day 3, there is a transient drop in the number of detectable PPARγ target sites, while the numbers increase significantly at days 4 and 6. ChIP-PCR analysis of PPARγ:RXR binding on three different biological replicas confirmed that PPARγ occupancy drops at day 3 for most binding sites, but that it remains detectable by ChIP-PCR, indicating that the low number may be a matter of sensitivity (Supplemental Fig. S3). The extent of this drop in occupancy at day 3 varies between different differentiations, but the observation is robust. Notably, 94%–100% of the shared PPARγ:RXR target sites found at days 0–4 were also shared target sites at day 6, indicating that once bound by the PPARγ:RXR heterodimer, these sites retain their accessibility, although occupancy drops on day 3.

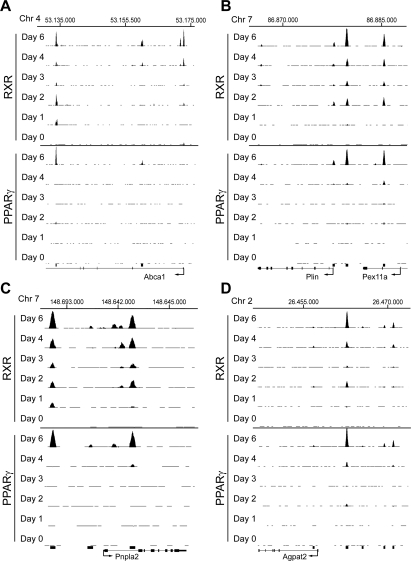

In contrast to PPARγ, RXR binds to >1000 target sites already at the preadipocyte stage, and we detect several thousand RXR-binding sites throughout the differentiation process. We cannot rule out that the high number of RXR target sites compared with PPARγ target sites is in part due to differences in recoveries between the antibodies used. However, the many RXR target sites at early states of differentiation are in agreement with RXR being a heterodimerization partner for several other nuclear receptors. As an example of this, the Abca1 gene contains an “RXR-only” site previously characterized as an LXR:RXR-binding site in the proximal promoter region (Fig. 2A; Supplemental Fig. S4A; Uehara et al. 2007). In addition, shared PPARγ:RXR target sites are identified in that locus.

Figure 2.

Identification of PPARγ:RXR-binding sites at selected gene loci during adipocyte differentiation. (A–D) ChIP-seq data during 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation viewed in the University of California at Santa Cruz (UCSC) browser showing PPARγ- and RXR-binding sites for Abca1 (Y-axis scale on PPARγ and RXR tracks 10–70) (A), Plin and Pex11a (Y-axis scale on PPARγ and RXR tracks 10–150) (B), Pnlpa2 (Y-axis scale on PPARγ and RXR tracks 10–90) (C), and Agpat2 (Y-axis scale on PPARγ and RXR tracks 10–200) (D). The Y-axis shows the number of mapped tags. Base positions are indicated above all binding profiles. Black bars below the tracks indicate PPARγ:RXR target sites detected at day 6. See Supplemental Figure S4 for further details.

Throughout differentiation, we detect a large number of “PPARγ-only” and “RXR-only” sites. Notably, however, we found that a high percentage of these (e.g., 75% of day 4 PPARγ-only sites and 69% of day 4 RXR-only sites) sites become occupied by the PPARγ:RXR heterodimer at day 6. This indicates that the heterodimer composition may change throughout adipogenesis and/or that there are several PPARγ:RXR-binding sites, where occupancy of one heterodimerization partner falls just below detection limit at the early days of differentiation. In support of this notion, we find that if tested by ChIP-PCR, some but not all sites detected as RXR-only-binding sites at day 2 or 3 are indeed occupied by both PPARγ and RXR at these days (Supplemental Fig. S3). In addition, we find that several sites identified as PPARγ-only at day 6 display RXR occupancy when tested by ChIP PCR (Supplemental Fig. S1). Variations and a low degree of overlap among low-intensity binding sites have been published previously for STAT1 and p53 ChIP–chip data (Euskirchen et al. 2007; Smeenk et al. 2008).

Genomic location of PPARγ:RXR target sites

Using PinkThing (http://pinkthing.cmbi.ru.nl), we assigned the 5236 identified PPARγ:RXR-binding sites detected on day 6 to a total of 3352 genes based on proximity, and target sites were grouped depending on their position relative to the nearest gene (Fig. 1D). This analysis shows that only 10% of all PPARγ:RXR-binding sites in mature adipocytes are located within the first 5 kb upstream of the transcriptional start site (TSS). Notably, 50% of all target sites are located within genes. A similar high percentage of intragenic binding sites was shown recently for ERα in MCF-7 cells and in mouse liver (Carroll et al. 2006; Gao et al. 2008). Another noticeable feature is that numerous genes have several adjacent PPARγ: RXR-binding sites.

The shared PPARγ:RXR target sites identified throughout adipocyte differentiation encompass several of the previously reported PPARγ:RXR regulatory target sites and numerous novel binding sites near well-characterized, as well as novel, putative PPARγ-regulated genes (Fig. 2A–D; Supplemental Fig. S4A–D). Among these, we confirm PPARγ:RXR binding to the well-established PPREs located between the PPAR target genes perilipin (Plin) and Pex11a (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Fig. S4B). In addition to the previously characterized binding site (Nagai et al. 2004; Shimizu et al. 2004), we identify a novel target site within the first intron of Pex11a as well as a less-intense PPARγ:RXR-binding site at the TSS of Plin. For the recently identified PPAR target gene Pnpla2 (Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 2) encoding adipocyte triglyceride lipase (Atgl), we identify two novel target sites (Fig. 2C; Supplemental Fig. S4C); one located ∼3000 base pair (bp) upstream of the TSS, just outside a previously investigated proximal promoter region (Kim et al. 2006), and a binding site in intron 1, as recently proposed (Kershaw et al. 2007). Furthermore, the acylglycerophosphate transferase 2 (Agpat2) gene encoding one of the enzymes involved in triglyceride syntheses was recently reported to be important for adipocyte differentiation (Gale et al. 2006). However, no regulatory elements have been identified for this gene. We identify clear PPARγ and RXR binding to a target site 10 kb upstream of the TSS as well as minor PPARγ:RXR binding to several adjacent target sites (Fig. 2D; Supplemental Fig. S4D).

Motif search reveals DR1 as the predominant cis-acting element

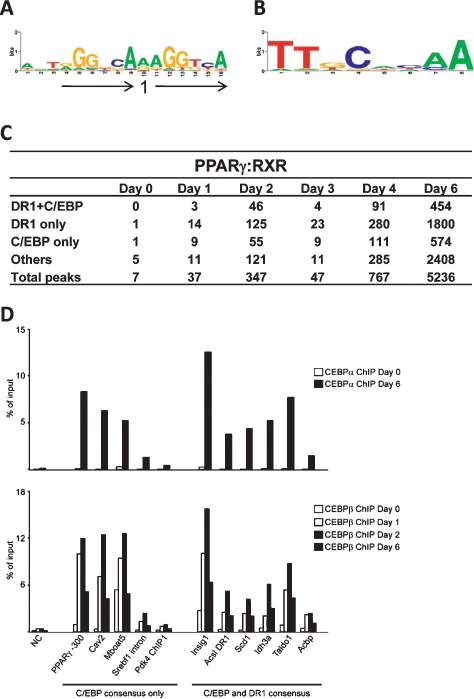

To elucidate specific sequence motifs underlying PPARγ- and RXR-binding sites at the different days of differentiation, a de novo motif search was performed. When searching for motifs with length between 15 and 25 bp, the analysis almost exclusively yielded motifs reminiscent of DR1. Thus, our genome-wide analysis of in vivo binding sites corroborates and extends DR1 as the main cis-acting element for high-affinity binding of PPARγ:RXR heterodimers. We observe higher conservation of the RXR bound (3′) than of the PPARγ 5′ half-sites, in agreement with earlier reports (Temple et al. 2005). In addition, we observe some conservation of the 5′ sequence flanking sequence reminiscent of the previously reported 5′ extension (Hsu et al. 1998).

Based on the DR1 motifs found in the de novo search, a common Position Weight Matrix (PWM) for the DR1 motif was created and used to scan all the PPARγ- and RXR-binding sites detected during differentiation (Fig. 3A–C; Supplemental Table S2). Interestingly, even though the highest abundance of DR1 elements is found at shared PPARγ:RXR sites, DR1 is also highly represented in RXR-only- and PPARγ-only-binding sites. The large number of DR1 containing RXR-only sites at the early phase of adipogenesis suggests that RXR hetero/homodimers other than PPARγ:RXR may bind to PPREs in the early phase of adipogenesis. Furthermore, this suggests that the specificity of the DR1 to distinguish between PPARγ:RXR dimers and possibly other hetero/homodimers is not determined by the central motif, a notion that is further supported by the finding that PWM’s independently established for the shared PPARγ:RXR- (days 4 and 6) and RXR-only-binding sites (days 0–2) are nearly identical (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Co-occurrence of DR1 and C/EBP motifs at shared PPARγ:RXR-binding sites. (A) Web logo of DR1 consensus motif PWM generated based on de novo motif search of PPARγ:RXR-binding sites. (B) Web logo of C/EBP consensus motif PWM derived from combined C/EBP-like motifs that were revealed by the MD module in the RXR-only-binding sites of days 0–2 and the shared PPARγ:RXR-binding sites of days 4–6 (see the Materials and Methods for details). (C) The number of matches for co-occurring DR1 + C/EBP, single occurrences of DR1 and C/EBP, and occurrence of other motifs in shared PPARγ:RXR-binding sites at the indicated days. (D) C/EBP transcription factors occupies shared PPARγ:RXR sites. Chromatin isolated at the indicated days of differentiation, and ChIP-PCR was performed using antibodies against C/EBPβ or C/EBPα. (NC) No gene control. Recoveries are shown as the percent of input. Results are representative of at least two experiments.

Motif searching with lengths between 8 and 10 bp yielded more candidate motifs, one of the abundant being the DR1 half-site. The occurrence of the half-site did not vary much from that of the DR1 (data not shown). Another well-scoring motif was that of the C/EBPs, a family of transcriptional regulators involved in adipogenesis. A C/EBP consensus site PWM was generated and used to screen for occurrence of C/EBP sites at PPARγ- and RXR-binding sites (Fig. 3B,C; Supplemental Table S2). The DR1 and C/EBP motifs co-occur at relatively high frequency, and the distance between these co-occurring DR1 and C/EBP motifs varied primarily between 1–140 bp with an average distance of 91 bp for all shared binding sites but no preference for a particular distance (Supplemental Fig. S5). These results suggest that C/EBPs and PPARγ:RXR are binding in close proximity and are likely to cooperate in binding and/or transcription regulation. Another remarkable finding is the high percentage of C/EBP motifs without an accompanying DR1. Interestingly, ChIP-PCR showed that C/EBPα is indeed associated with 10 out of 11 investigated PPARγ:RXR target sites overlapping with a C/EBP consensus sequence in adipocytes (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, C/EBPβ occupancy is detected at the same sites, but occupancy in this case peaks at day 2. This pattern of C/EBP occupancy is in keeping with the expression pattern of C/EBP subtypes and previous ChIP-PCR analyses of C/EBP binding to well-established C/EBP sites including the well-characterized C/EBP-binding site in the PPARγ2 proximal promoter (position −300) (Salma et al. 2006). Notably, C/EBP factors were found to co-occupy PPARγ:RXR-binding sites both with and without a consensus DR1 element.

Differential recruitment of PPARs and RXR to target sites during adipogenesis

The fact that we see a large number of RXR-binding sites without PPARγ early in differentiation as well as differences between the relative, temporal recruitment of PPARγ and RXR, indicated that other receptors than PPARγ might dimerize with RXR for binding to these sites and may play a role in the early phase of differentiation. One likely candidate for RXR heterodimerization is PPARδ, which is expressed at low constitutive levels throughout differentiation and has been reported to potentiate PPARγ-stimulated adipocyte differentiation and directly activate some PPARγ target genes (Hansen et al. 2001; Matsusue et al. 2004).

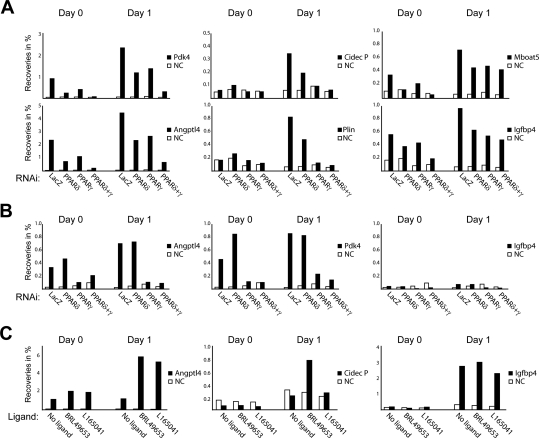

To investigate the relative contribution of PPARγ and PPARδ as heterodimerization partners of RXR on these sites at early stages of differentiation, we generated lentiviral vectors for shRNA-mediated knockdown of PPARγ and PPARδ, respectively. Analysis of mRNA expression showed a robust (70%–90%) and specific knockdown of PPARδ and PPARγ, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S6). PPARα mRNA was not detectable in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes.

Interestingly, when we examined the RXR occupancy at several PPARγ:RXR-binding sites, we observed that the investigated target sites could be split up in different groups based on the relative contribution of PPARδ:RXR and PPARγ:RXR heterodimers to RXR occupancy (Fig. 4A). First, on the few PPARγ:RXR-binding sites that are occupied already at day 0 (e.g., target sites adjacent to Pdk4 and Angptl4), knockdown of either PPARδ or PPARγ resulted in reduction of RXR binding. Further reduction of RXR binding was observed by knockdown of both PPARs. This suggests that PPARγ and PPARδ are bound to these sites very early during adipogenesis. A second group of sites established early in differentiation includes, e.g., binding sites at the Cidec promoter and the Plin enhancer (Fig. 4A) as well as binding sites adjacent to the Obcf2b gene and a peak identified at −3000 of the Cidec gene (data not shown). RXR occupancy was dramatically reduced by knockdown of PPARγ and to a variable degree also by PPARδ knockdown. This indicates that even early in differentiation, establishment of RXR binding to these target sites is mainly dependent on PPARγ. Finally, target sites assigned to Igfbp4 and Mboat5 (Fig. 4A), as well as binding sites assigned to Acox1, Pex13, and Adipor2 (data not shown) have substantial RXR occupancy even if both PPARγ and PPARδ are knocked down. Thus, these sites are likely to be occupied by non-PPAR RXR hetero-/homodimers prior to PPAR:RXR heterodimer binding later in adipogenesis. In keeping with this, we were unable to detect PPARγ occupancy at the site assigned to Igfbp4 at the early days (Fig. 4B). In contrast, PPARγ occupancy was readily detected at the sites assigned to Angptl4 and Pdk4, and knockdown of PPARγ resulted in almost complete ablation of PPARγ occupancy (Fig. 4B). Importantly, no reduction of PPARγ occupancy was observed upon PPARδ knockdown at any of the sites investigated (Fig. 4B; data not shown). Together these data indicate that a considerable amount of RXR binding on several target sites at the early days of differentiation may represent RXR hetero-/homodimers other than PPARγ:RXR.

Figure 4.

Temporal and compositional differences in RXR dimer occupancy at PPARγ:RXR-binding sites in early adipogenesis. (A) Effect of PPARδ and PPARγ knockdown on binding of RXR to target sites at days 0 and 1. Preadipocytes were infected with shRNA-expressing lentivirus prior to confluence. shRNAi directed against LacZ was used as control. Chromatin was isolated at days 0 and 1, and RXR ChIP-PCR was performed for the indicated target sites. Recoveries are shown as the percent of input. (NC) No gene control. (B) PPARγ ChIP-PCR for the indicated target sites on the same chromatin as in A. (C) Day 0 and day 1 preadipocytes were treated with a specific agonist of PPARγ (1 μM BRL49653/rosiglitazone) or PPARδ (1 μM L165041) for 6 h before chromatin was harvested. RNAPII ChIP-PCR was performed using primers located within the body of the indicated genes. RNAPII antibody and DNA were analyzed as in A. All results are representative of a minimum of two independent experiments.

To further evaluate the nature of RXR heterodimers occupying the different types of target sites, we treated preadipocytes with PPAR subtype-specific agonists and determined intragenic RNAPII occupancy at target genes. In keeping with the knockdown results, we found that agonists for PPARγ (rosiglitazone) as well as PPARδ (L165041) were able to induce an increase in RNAPII occupancy at the gene encoding Angptl4, whereas only PPARγ agonists are able to enhance RNAPII occupancy at the Cidec gene, where RXR binding is primarily dependent on PPARγ (Fig. 4C). In contrast, no increase in RNAPII occupancy was observed on the Igfbp4 gene. These results are in agreement with the observation that Igfbp4-adjacent binding sites retain RXR binding even if both PPARs are knocked down. Collectively, our results suggest a role for PPARγ-independent RXR binding to target sites early during adipocyte differentiation.

Transcriptional regulation during adipogenesis

In order to map active transcription by RNAPII during adipogenesis and to couple this to PPARγ and RXR occupancy, we determined the occupancy of the RNAPII by genome-wide RNAPII ChIP-seq during adipocyte differentiation. The number of annotated sequence tags within Ensembl genes (from +250 to the end of the gene) was determined for genes larger than 1 kb and used as a measure of transcriptional activity. Regions encompassing promoters were avoided in order not to compromise our analysis by the presence of paused RNAPII at the promoter without productive transcription (Margaritis and Holstege 2008). In the RNAPII profiles (e.g., see Supplemental Fig. S7), we observe “waviness” of RNAPII occupancy within individual genes. This waviness is due in part to the presence of numerous repeat sequences scattered around the genome and is commonly observed in profiles of RNAPII or histone marks. As repetitive sequences are not unique, they cannot be annotated and placed on the genome track, and the presence of a “valley” indicates the presence of such repetitive sequences (Wang et al. 2008).

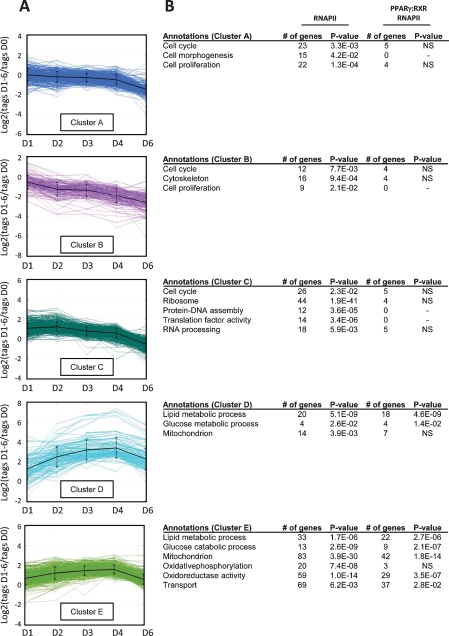

Significantly expressed genes are defined as those having a minimum of eight sequence tags per 1 kb on at least 2 d. By relating these numbers of sequence tags to that at day 0 we determined the fold induction or repression of transcriptional activity relative to day 0. The regulated genes were subjected to cluster analysis using the k-means algorithm and five distinct clusters were identified encompassing a total of 1625 regulated genes (Fig. 5A). Gene Ontology (GO) analyses reveal several functional categories in which regulated genes are overrepresented (Fig. 5B). Due to the hierarchical structure of GO categories, the same gene can be assigned with multiple GO terms. In clusters A and B, we find genes functionally linked to cell morphogenesis and cytoskeleton. RNAPII occupancy on these genes decreases from day 0 to day 6 (Fig. 5B), probably reflecting the change in cell motility and exit from cell cycle during the acquisition of the adipogenic phenotype. Genes such as those encoding proteins involved in actin organization (e.g., Cdc42 effector protein 1 and Cofilin-1) map to these two clusters. In contrast, cluster C contains genes that show a transient increase in RNAPII occupancy at days 1 and 2. Genes linked to cellular proliferation—i.e., cell cycle (e.g., Chromosome condensation protein 1 and several cyclins), RNA processing (e.g., RNA splice factors), and ribosome and translation factor activity (e.g., ribosomal structural proteins, and translation initiation and elongation factors)—map to this cluster. These findings are in agreement with the induction of clonal expansion and subsequent requirement for growth arrest before terminal differentiation can occur (Otto and Lane 2005). In addition, cluster C also contains genes encoding transcription factors the expression of which peaks during early adipogenesis; e.g., Cebpb and Egr2 (Krox20) (Rosen and MacDougald 2006).

Figure 5.

Clustering of genes based on their changes in RNAPII occupancy during differentiation reveals five distinct clusters. RNAPII ChIP-seq was performed during differentiation, and the relative overall occupancy in the genes was calculated as described using Log2 ratios of RNAPII occupancy at each day relative to day 0. (A) Genes with regulated RNAPII binding were separated into five distinct clusters using the k-means algorithm with squared Euclidean distance. (B) The clustered genes were assigned to biological function based on GO using the web tool DAVID. The total number of genes within a given cluster that belongs to a particular GO category as well as the P-value for the category is indicated (RNAPII). The number of genes with associated PPARγ:RXR target sites is listed with the corresponding P-values (PPARγ:RXR RNAPII). Significance level: P < 0.05; (NS) not significant.

Clusters D and E contain genes with increased RNAPII occupancy during differentiation (Fig. 5A). Several genes are functionally grouped within GO categories involved in glucose and lipid metabolic processes and oxidoreductase activity (Fig. 5B). Cluster E contains a large group of genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation (e.g., NADH dehydrogenases, cytochrome c oxidases, and parts of the ATP synthase mitochondrial F0 complex). In both clusters, D and E genes coding for proteins implicated in lipid metabolic processes are overrepresented. These include well-described genes such as Agpat2, Lpl, and Plin involved in the synthesis, transport, and storage of triglycerides as well as genes encoding the SCD1 and SCD2 fatty acid desaturases. The binding of RNAPII to genes within the functional annotated groups of clusters D and E is in accordance with the role of the adipocyte in lipid storage and lipid handling.

The RNAPII occupancy on genes correlated well with ongoing transcription as measured by qPCR using intron–exon primer pairs for detection of the primary transcript (pre-mRNA) (Supplemental Fig. S8). The median Spearman correlation factor between RNAPII occupancy and primary transcript levels for 30 genes is 0.83 (Supplemental Table S3). In agreement with the RNAPII occupancy, we observe a drop during adipogenesis in primary transcript levels from genes in clusters A and B, such as Cdkn2a and Actb (Supplemental Fig. S8). In contrast, primary transcripts from genes encompassed in clusters D and E, such as Lpl and Pgk1, are progressively induced during differentiation. In keeping with the fact that mRNA levels not only depend on transcription but also on stability, mRNA levels correlated less well with RNAPII occupancy (median Spearman correlation factor 0.60) (Supplemental Table S3; Supplemental Fig. S8). In order to relate high-confidence shared PPARγ:RXR-binding sites to transcriptional regulation, we investigated how many of the active RNAPII-occupied genes had shared PPARγ:RXR target sites assigned (Supplemental Table S4). Interestingly, regulated genes with assigned PPARγ:RXR target sites are very significantly associated with the up-regulated genes of cluster D and E but not with clusters A, B, and C (Fig. 5B). In fact, more than half of all induced genes (53%)—i.e., 74% and 47% of the regulated genes in clusters D and E, respectively—have PPARγ:RXR-binding sites assigned. Thus, cluster D, which contains genes that are more dramatically induced during adipogenesis as compared with cluster E, has the highest occurrence of assigned PPARγ:RXR target sites. Notably, all GO categories identified in clusters D and E, except the oxidative phosphorylation pathway, had a significant association with PPARγ:RXR target sites. Our finding corroborates and extends the importance of PPARγ:RXR as regulator of the adipocyte gene program and very importantly indicates that PPARγ:RXR directly activates a much broader spectrum of adipocyte genes than previously recognized.

PPARγ:RXR occupancy in the PPARγ and C/EBPα loci

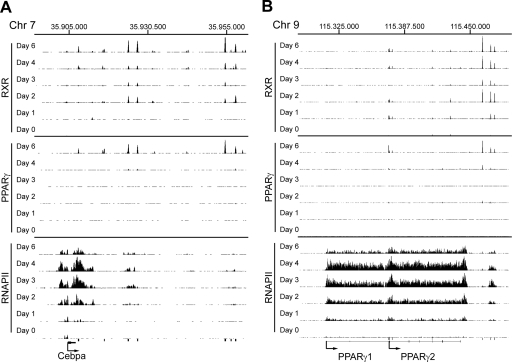

PPARγ has been reported to directly activate the expression of several transcription factors of importance for adipogenesis as well as lipogenesis. Importantly, PPARγ and C/EBPα have been shown to mutually activate the expression of each other, thereby supporting the maintenance of the differentiated stage. Our motif analysis further suggests that PPARγ:RXR and C/EBPs cooperate in binding and/or transcription regulation during adipogenesis. A C/EBP-binding site has been reported in the PPARγ2 promoter (Clarke et al. 1997); however, a PPARγ regulatory sites in the C/EBPα locus has not been identified. Visual inspection of the C/EBPα locus shows two prominent PPARγ:RXR target sites ∼20 kb downstream from the gene and two less-intense PPARγ:RXR peaks, one just downstream from the gene and another ∼8 kb downstream (Fig. 6A). Both of the latter as well as one of the prominent peaks overlap with a DR1 sequence.

Figure 6.

PPARγ:RXR binding and RNAPII occupancy at Cebpa and PPARγ loci. ChIP-seq data are viewed in the University of California at Santa Cruz browser for the Cebpa locus (Y-axis scale on PPARγ and RXR tracks 10–90 and RNAPII tracks 5–50) (A) and the PPARγ locus (Y-axis scale on PPARγ and RXR tracks 10–200 and RNAPII tracks 5–60) (B). Black bars below the tracks indicate PPARγ:RXR target sites detected at day 6.

Interestingly, we also observe PPARγ:RXR-binding sites just upstream of the PPARγ2 promoter (Fig. 6B). These sites encompasse the reported C/EBP-binding site, as well as an additional C/EBP consensus site (data not shown), suggesting that on these sites, PPARγ:RXR binding may be established via DNA-bound C/EBP. Indeed, we observe that C/EBPβ and C/EBPα are associated with this region (Fig. 3B). In addition, we observe PPARγ:RXR binding to three prominent sites ∼15–25 kb downstream from the PPARγ locus, and one of these sites overlaps with a DR1 consensus.

It is well established that PPARγ agonists induce the expression of their own receptor in developing adipocytes (Lehmann et al. 1995), and it has been suggested that PPARγ induces the expression of C/EBPα, which in turn activates the PPARγ2 promoter. Our results indicate that PPARγ may also activate its own expression as well as that of C/EBPα by directly targeting sites located in the 3′ distal region as well as in the promoter of these loci. Future studies will be required to dissect the importance of the identified target sites.

Clustering of metabolic pathways regulation reveals distinct temporal activation

GO analysis of regulated genes with adjacent PPARγ: RXR-binding sites showed that these, in particular, cluster in categories involved in lipid and glucose metabolism (Fig. 5B). This observation is strengthened by a more in-depth investigation of metabolic pathways, which reveals that almost all genes encoding proteins involved in fatty acid handling and storage (fatty acid uptake, glycerolipid synthesis, and lipid droplet associated proteins) as well as lipolysis have adjacent PPARγ: RXR-binding sites and thus are potentially regulated by PPARγ (Fig. 7). Examples of these genes include previously well-characterized PPARγ target genes such as Plin and lipoprotein lipase (Lpl), in addition to Acsl1, Agpat2, and several genes that have not been described previously as direct PPARγ target genes (Supplemental Fig. S7A–D). Interestingly, most genes encoding enzymes in the glycolytic pathway as well as the pentose phosphate pathway also have nearby PPARγ:RXR target sites (Fig. 7). These include HK2 and Taldo1 (Supplemental Fig. S7E,F).

Figure 7.

PPARγ:RXR binding is associated with the majority of the genes involved in glucose and lipid metabolism. Genes with at least one assigned PPARγ:RXR site (by PinkThing) are marked in green. The letter in the parentheses denotes which cluster the gene belongs to according to the profile of RNAPII occupancy (Fig. 5). Genes with previously described adjacent PPARγ:RXR sites are indicated with an asterisk. (LD) Lipid droplet; (TCA) tricarboxylic acid cycle. Gene names are provided in Supplemental Table S5.

In order to investigate the functional importance of the PPARγ:RXR target sites, we knocked down PPARγ expression prior to induction of differentiation and determined the ability of PPARγ to activate gene expression of these genes at day 2. By limiting the analyses to early time points, we circumvent the fact that blunting PPARγ expression will inhibit differentiation and the induction of other transcription factors that might regulate these genes. The results clearly demonstrate that PPARγ plays a critical role in the induction of multiple putative target genes already at this early time point (day 2) of differentiation (Supplemental Fig. S9).

In addition, to test if expression of the same set of genes is sensitive to PPARγ agonists, we treated day 6 adipocytes for 12 h with the PPARγ-selective ligand rosiglitazone (Supplemental Fig. S10). This treatment led to a modest but significant increase in the mRNA level of well-characterized target genes such as Fabp4 and Gpd1, as well as many novel putative target genes involved in lipogenesis (Agpat2, Acsl1, Gpat3) and glucose metabolism (Hk2, Taldo1). This suggests that these genes are indeed direct PPARγ:RXR target genes. The relatively modest induction is explained by the high level of these transcripts in adipocytes; the fact that transcription of these genes is controlled by multiple factors; and probably by the presence of the endogenous agonists. Notably, most of the target genes involved in lipogenesis and lipid storage are found in cluster D, whereas genes encoding enzymes in the glycolytic pathway as well as the pentose phosphate pathway predominantly cluster in E (Fig. 7).

In conclusion, our data provide a comprehensive genome-wide map of RNAPII occupancy during adipocyte differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells and represent, to our knowledge, the first global RNAPII profile through a differentiation process. Interestingly, PPARγ:RXR-binding sites are found in the vicinity of more than half of all genes to which RNAPII occupancy is induced during adipocyte differentiation, thereby supporting the role of PPARγ not only in adipogenesis per se but also as a direct regulator of a large number of genes expressed in mature adipocytes.

Discussion

In this study, we present the first genome-wide ChIP-seq profiling of PPARγ- and RXR-binding sites and RNAPII occupancy in mature adipocytes and throughout adipogenic differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells. The combination of a comprehensive and high-resolution genome-wide map of PPARγ:RXR target sites and a global map of RNAPII occupancy enables us to correlate PPARγ:RXR binding at a genome-wide scale with transcriptional events during adipogenesis.

The largest number of shared PPARγ:RXR target sites were identified in mature adipocytes (day 6), where a total of 6952 and 8228 binding sites were mapped for PPARγ and RXR, respectively. Of these, 5236 were shared high-confidence PPARγ:RXR-binding sites. In contrast, at the onset of differentiation (days 0–1), few of these are occupied, and in several cases, only RXR occupancy can be detected by ChIP-seq. Interestingly, RNAi experiments as well as agonist experiments indicate that PPARδ:RXR occupy several RXR target sites that later become occupied by PPARγ:RXR. Moreover, we observe different temporal and compositional patterns of occupancy through the early days of differentiation. Thus, RXR binding to some targets sites on day 0 is PPARδ-dependent but become highly PPARγ-dependent with only little PPARδ dependency at day 1. In contrast, other sites are primarily occupied by non-PPAR RXR hetero- or homodimers at days 0 and 1. In addition, we identify a very small group of sites that are co-occupied by PPARγ: RXR and PPARδ:RXR heterodimers already at day 0.

The early PPARδ:RXR occupancy at PPARγ:RXR target sites may account for the reported ability of PPARδ to promote and/or counteract adipogenesis (Hansen et al. 2001; Shi et al. 2002; Matsusue et al. 2004). It has previously been shown that an exchange from early C/EBPβ to late C/EBPα binding occurs at C/EBP response elements during adipocyte differentiation (Salma et al. 2006). Our data suggest that a similar mechanism could regulate the transcription factor association with PPARγ: RXR-binding sites as differentiation progresses. The early RXR binding prior to the presence of PPARγ on the late PPARγ:RXR target site might serve as a mark needed for subsequent PPARγ-dependent binding and/or activation of transcription of the corresponding target genes. A temporal exchange in RXR partners on these sites might, for example, be required for the remodeling of such loci in order to render these ready for PPARγ binding and subsequent transactivation. Our investigations indicate temporal differences in PPARγ binding to distinct classes of PPAR:RXR-binding sites and support a model where PPARγ is recruited to some RXR preoccupied target sites, as well as sites not previously bound by RXR during adipogenesis. Additional binding studies throughout adipogenesis using ChIP-grade antibodies for PPARδ and other potential RXR partners are needed to further substantiate when and how receptor subtypes are exchanged at PPARγ:RXR target sites.

It remains unclear why certain sites are occupied by the PPARγ:RXR heterodimer at early time points, when PPARγ levels are very low. It is possible that the heterodimer has particularly high affinity for these DNA sites or that the chromatin structure and epigenetic markings are particularly favorable. Alternatively, there may be synergistic binding through interaction of multiple heterodimers or through interaction with other transcription factors such as C/EBPs. Notably, similar 5′ half-site conservation was found when motif searches were conducted separately using RXR-only-binding site sequences from days 0–2 or shared PPARγ:RXR-binding sites at late stage of adipogenesis (data not shown). The high degree of DR1 conservation, even for non-PPARγ-bound sites, suggests that the DR1 sequence per se is not discriminating between different RXR heterodimers.

A de novo motif search of the RXR- and PPARγ-binding site sequences yielded the DR1 as the overriding motif, thereby confirming the importance of DR1 sequences for PPARγ:RXR dimers in binding to the genome (Palmer et al. 1995). Motif searches with width 8 to 10 yielded the DR1 half-site and the C/EBP motif as main candidates. Interestingly, we observe abundant co-occurrence of C/EBP and DR1 motifs that are primarily between 1 and 140 bp apart. Of importance, C/EBPα and C/EBPβ ChIP-PCR confirmed that C/EBPα and C/EBPβ bind to 10 out of 11 PPARγ:RXR target sites encompassing a C/EBP consensus sequence (Fig. 3D). This indicates that there is indeed a high degree of overlap between PPARγ:RXR- and C/EBP-binding sites, and that members of the C/EBP family directly cooperate with PPARγ:RXR in the activation of a hitherto unrecognized number of target genes. In some cases, C/EBPs and PPARγ:RXR may bind to neighboring sites, whereas in other cases, co-occupancy (in particular, where no DR1 elements can be found) may be due to looping and interaction between PPARγ:RXR and C/EBP complexes located at distant sites. Indeed, we observe numerous PPARγ:RXR-binding sites, where only a C/EBP consensus is found without the presence of a DR1 consensus, supporting the idea that PPARγ:RXR may bind indirectly to DNA possibly via looping and interaction with C/EBP-containing complexes. The functional significance of C/EBP and PPARγ:RXR co-occupancy remains to be determined; however, one possibility is that C/EBPβ and C/EBPα by means of their ability to recruit the high mobility group I nonhistone proteins [HMGI (Y)] (Melillo et al. 2001) and the SWI/SNF complex (Kowenz-Leutz and Leutz 1999; Pedersen et al. 2001), respectively, render chromatin more accessible to PPARγ:RXR.

Our genome-wide maps of RNAPII occupancy throughout the gene body provide a direct readout of transcriptional activation or repression by transcription factors and thus yield insights beyond what is typically obtained by mRNA expression profiling. Our analysis shows that RNAPII occupancy and transcriptional activity measured as the level of pre-mRNA (short-lived primary transcript) correlate very well (median Spearman correlation factor of 0.83), whereas the correlation with mature mRNA is lower as differential stability of the mRNA contributes to the level of transcript accumulation. In agreement, a very recent analysis of the transcriptome by deep sequencing also demonstrated a good correlation between RNAPII occupancy at promoters and the level of transcription (Sultan et al. 2008). Our analysis clearly shows that RNAPII occupancy in the body of genes serves as an excellent measure transcriptional activity over the respective loci.

Based on the temporal pattern of RNAPII occupancy, we defined specific clusters of similarly regulated genes during adipocyte differentiation. Clusters containing genes with decreased RNAPII occupancy during differentiation are highly enriched for genes involved in cytoskeleton and cell morphogenic processes, reflecting the changes of the cellular cytoskeleton associated with the conversion from elongated fibroblast morphology to a more-rounded adipocyte shape. Another cluster contains genes that show a transient increase in RNAPII occupancy at days 1 and 2. Genes involved in cellular proliferation—i.e., cell cycle, protein–DNA assembly, and RNA processing—map to this cluster. These findings are in agreement with the induction of clonal expansion during the early phase of preadipocyte conversion to mature adipocytes (Bernlohr et al. 1985) and with other reports on gene expression during adipogenesis (Ross et al. 2002). In contrast, two clusters show increased RNAPII occupancy during adipocyte differentiation. These clusters contain several functionally related genes within lipid metabolism in particular, but also within carbohydrate metabolism, mitochondrial function (including oxidative phosphorylation), oxidoreductase activity, and transport. The most significantly induced group of genes (cluster D) encompasses a large number of genes involved in lipid metabolism.

Interestingly, when target sites were assigned to genes based on proximity, we find that PPARγ:RXR-binding sites are particularly enriched in the vicinity of genes to which RNAPII occupancy is induced during adipogenesis (clusters D and E). In fact, 74% and 47% of the induced genes in clusters D and E, respectively, could be assigned to nearby PPARγ:RXR-binding sites. We found that PPARγ:RXR binding could be associated with a significant number of genes involved in glycerolipid handling, synthesis, and storage. Surprisingly, also a large number of genes encoding enzymes involved in glucose metabolism, including glycolysis, glyceroneogenesis, and the pentose phosphate pathways, have adjacent PPARγ:RXR-binding sites. PPARγ has been reported previously to regulate glucose metabolism in adipocytes (Anghel et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2007). In particular, genes encoding enzymes involved in adipogenic glycerol synthesis from pyruvate and glucose such as Pepck and Gpd1 have been shown to be PPARγ targets (Reshef et al. 2003; Patsouris et al. 2004). However, the data presented here indicate that the transcriptional regulation of glucose metabolism by PPARγ:RXR potentially goes beyond the regulation of glycerol synthesis and includes the majority of the enzymes involved in breakdown and modulation of glucose. The direct involvement of PPARγ in the regulation of several of these genes was confirmed using RNAi and a PPARγ-specific agonist. It is thus likely that PPARγ:RXR-regulated transcription could play a central role to meet the specified metabolic needs of the adipocyte not just to handle lipids, but also to stimulate production of redox equivalents for de novo lipogenesis and glycerol for use in glycerolipid synthesis.

In conclusion, these data provide a comprehensive genome-wide map of RNAPII occupancy during adipocyte differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells and represent, at least to our knowledge, the first approach to directly link global RNAPII profiles with nuclear receptor-binding sites through a differentiation process. Our study also provides the first positional and temporal map PPARγ and RXR occupancy during adipocyte differentiation at a global scale. We show that at the early days of differentiation, several of these sites bind not only PPARγ:RXR but also PPARδ:RXR as well as non-PPAR RXR hetero-/homodimers. Importantly, our data also provide a comprehensive temporal map of RNAPII occupancy at genes throughout 3T3-L1 adipogenesis, thereby uncovering groups of similarly regulated genes belonging to glucose and lipid metabolic pathways. The majority of the up-regulated but very few down-regulated genes have assigned PPARγ:RXR target sites, thereby underscoring the importance of PPARγ:RXR in gene activation during adipogenesis and indicating that a hitherto unrecognized high number of adipocyte genes are directly activated by PPARγ:RXR.

Materials and methods

3T3-L1 cell culture

The 3T3-L1 fibroblasts were differentiated to adipocytes by stimulation with 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, dexamethasone, and insulin as described previously (Helledie et al. 2002). Cells were harvested at days 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 during adipocyte differentiation, and protein, mRNA, and chromatin were prepared and analyzed by Western blotting, RealTime qPCR, and ChIP as described previously (Nielsen et al. 2006).

ChIP and ChIP-seq

ChIP experiments were performed according to standard protocol as described in Nielsen et al. (2006). The antibodies used were RNAPII antibody (AC-0555-100; Diagenode), PPARγ antibody (H-100, sc7196; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), RXR antibody (Δ197, sc774; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), C/EBPα antibody (14AA, sc61; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), and C/EBPβ antibody (C-19, sc150; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies). ChIP-seq sample preparation for sequencing was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina).

Data analysis and normalization

The image files generated by the Genome Analyzer were processed to extract DNA sequence data and mapped to the mouse genome using the Illumina Analysis Pipeline allowing one mismatch. The total number of sequenced fragments and mapped fragments is shown in Supplemental Table 1.

To correct for differences in sequencing depth and mapping efficiency among ChIP-seq samples at different time points, the total number of tags of each ChIP-seq sample was uniformly equalized relatively to the sample with the lower number of tags. The RNAPII, RXR, and PPAR samples were normalized as independent groups.

Peak detection

Detection of putative PPARγ- and RXR-binding sites was performed using FindPeaks (Fejes et al. 2008) at an FDR level <0.001 for the normalized tracks. The FDR-based minimum height threshold was raised with three reads for every track.

Clustering of RNAPII-regulated genes

The number of sequence tags within Ensembl gene bodies (+250 bp to end of gene) was counted for genes of the normalized RNAPII tracks. Ratios of log2 values of the average sequence tag number per 1 kb were calculated for each day during differentiation relative to day 0, and regulated genes were assigned when deviating more than ±1.5 times standard deviations from the mean; genes <1 kb were filtered out; and a final requirement of minimally eight tags on at least 2 d was applied to reduce noise. Clustering was performed using the k-means algorithm with squared Euclidean distance. The best-fitting number of clusters (5) was determined using the Gap statistic (Tibshirani et al. 2001) coupled with an iterative clustering process with k ranging from 2 to 10. These clustering processes were performed using Gene ARMADA (A. Chatziioannou, P. Moulos, V. Aidinis, and F. Kolisis, in prep.), which can be accessed at http://www.eie.gr/nhrf/institutes/ibrb/programmes/metabolicengineering-softwaretools.html.

Annotation of genes

Overrepresented GO (Ashburner et al. 2000) categories within GO annotation of RNAPII-regulated genes were determined using the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID; http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov) (Dennis et al. 2003). Assigning binding sites to nearest genes was performed by PinkThing (http://pinkthing.cmbi.ru.nl). All sequence analyses were conducted based on the Mus musculus NCBI m37 genome assembly (mm9; July 2007) accessed from Ensembl (release 49).

Motif search

The coordinates of peak maxima for each peak set (PPARγ-only-, RXR-only-, and PPARγ:RXR-binding sites for each day) were collected and extended by 200 bp on each side to create 400-bp genomic windows. DNA sequences were retrieved using Galaxy (http://main.g2.bx.psu.edu), and five distinct sequence sets corresponding to RXR days 0–2 and PPARγ:RXR days 4, six binding sites were used for initial motif search. The motif discovery program MD module (Liu et al. 2002) was applied to each set with motif widths varying from 8 to 10 and from 15 to 25 using the top 100 sequences. The top 20 scoring output motifs for each length were collected, curated, and converted to PWMs, which were clustered and compared against JASPAR v3 database using STAMP (Mahony and Benos 2007). Motif clusters of interest were converted to consensus PWMs to search all the peak sets for the occurrence of the respective motifs, and a specific sequence background model was generated using the RSAT tools (van Helden 2003) and used to determine score cutoffs as described (Smeenk et al. 2008). After interrogating the input sequences for the consensus motifs, we determined the overlap among the outputs for each motif.

RNAi knockdown and ligand experiments

shRNAi oligo DNA directed against PPARδ, PPARγ, and lacZ was cloned into pSicoR PGK Puro vectors (Addgene), and lentiviral particles were produced in Human Embryonic Kidney 293T cells as described (Ventura et al. 2004). 3T3-L1 cells were infected with shRNAi-expressing lentivira and selected for 3–4 d before cells were harvested for ChIP experiments on day 0 or day 1 of differentiation as described.

For ligand experiments, 3T3-L1 cells at days 0 and 1 of differentiation were incubated with PPARγ (Rosiglitazone) or PPARδ (L165041) specific agonists for 6 h before harvest for ChIP experiments as described.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Real-time qPCR was performed using SYBR Green mix (Sigma) with an MX3000 machine (Stratagene). If possible, exon–exon junction-spanning primers were used for determinations of primary transcript levels and exon-spanning primers for mRNA levels. Expression levels were normalized to TfIIb mRNA, which did not significantly vary during adipocyte differentiation. The primer sequences used for real-time qPCR are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Mandrup and Stunnenberg laboratories for fruitful discussions and comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by grants to the EU FP6 STREP project X-TRA-NET and EU FP6 IP HEROIC, and grants from the Danish Natural Science Research Council, the Danish Diabetes Association, and the Lundbeck Foundation. We are grateful to P. Sauerberg, Novo Nordisk A/S, for rosiglitazone/BRL40653.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.501108.

References

- Anghel S.I., Bedu E., Vivier C.D., Descombes P., Desvergne B., Wahli W. Adipose tissue integrity as a prerequisite for systemic energy balance: A critical role for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:29946–29957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702490200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M., Ball C.A., Blake J.A., Botstein D., Butler H., Cherry J.M., Davis A.P., Dolinski K., Dwight S.S., Eppig J.T., et al. Gene Ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernlohr D.A., Bolanowski M.A., Kelly T.J., Lane M.D. Evidence for an increase in transcription of specific mRNAs during differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:5563–5567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll J.S., Meyer C.A., Song J., Li W., Geistlinger T.R., Eeckhoute J., Brodsky A.S., Keeton E.K., Fertuck K.C., Hall G.F., et al. Genome-wide analysis of estrogen receptor binding sites. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:1289–1297. doi: 10.1038/ng1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke S.L., Robinson C.E., Gimble J.M. CAAT/enhancer binding proteins directly modulate transcription from the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ 2 promoter. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;240:99–103. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis G., Sherman B., Hosack D., Yang J., Gao W., Lane H.C., Lempicki R. DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:P3. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-5-p3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euskirchen G.M., Rozowsky J.S., Wei C.L., Lee W.H., Zhang Z.D., Hartman S., Emanuelsson O., Stolc V., Weissman S., Gerstein M.B., et al. Mapping of transcription factor binding regions in mammalian cells by ChIP: Comparison of array- and sequencing-based technologies. Genome Res. 2007;17:898–909. doi: 10.1101/gr.5583007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer S.R. Transcriptional control of adipocyte formation. Cell Metab. 2006;4:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fejes A.P., Robertson G., Bilenky M., Varhol R., Bainbridge M., Jones S.J.M. FindPeaks 3.1: A tool for identifying areas of enrichment from massively parallel short-read sequencing technology. Bioinformatics. 2008.;24:1729–1730. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale S.E., Frolov A., Han X., Bickel P.E., Cao L., Bowcock A., Schaffer J.E., Ory D.S. A regulatory role for 1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate-O-acyltransferase 2 in adipocyte differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:11082–11089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509612200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H., Fält S., Sandelin A., Gustafsson J.A., Dalman-Wright K. Genome-wide identification of estrogen receptor α binding sites in mouse liver. Mol. Endocrinol. 2008;22:10–22. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green H., Kehinde O. Sublines of mouse 3T3 cells that accumulate lipid. Cell. 1974;1:113–116. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen J.B., Zhang H., Rasmussen T.H., Petersen R.K., Flindt E.N., Kristiansen K. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor δ (PPARδ)-mediated regulation of preadipocyte proliferation and gene expression is dependent on cAMP signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:3175–3182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005567200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helledie T., Grontved L., Jensen S.S., Kiilerich P., Rietveld L., Albrektsen T., Boysen M.S., Nohr J., Larsen L.K., Fleckner J., et al. The gene encoding the acyl-CoA-binding protein is activated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ through an intronic response element functionally conserved between humans and rodents. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:26821–26830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111295200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu M.H., Palmer C.N., Song W., Griffin K.J., Johnson E.F. A carboxyl-terminal extension of the zinc finger domain contributes to the specificity and polarity of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor DNA binding. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:27988–27997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.27988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai T., Takakuwa R., Marchand S., Dentz E., Bornert J.M., Messaddeq N., Wendling O., Mark M., Desvergne B., Wahli W., et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ is required in mature white and brown adipocytes for their survival in the mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004;101:4543–4547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400356101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw E.E., Schupp M., Guan H.P., Gardner N.P., Lazar M.A., Flier J.S. PPARγ regulates adipose triglyceride lipase in adipocytes in vitro and in vivo. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;293:E1736–E1745. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00122.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.Y., Tillison K., Lee J.H., Rearick D.A., Smas C.M. The adipose tissue triglyceride lipase ATGL/PNPLA2 is downregulated by insulin and TNF-α in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and is a target for transactivation by PPARγ. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006;291:E115–E127. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo. 00317.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer S.A., Sundseth S.S., Jones S.A., Brown P.J., Wisely G.B., Koble C.S., Devchand P., Wahli W., Willson T.M., Lenhard J.M., et al. Fatty acids and eicosanoids regulate gene expression through direct interactions with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors α and γ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1997;94:4318–4323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowenz-Leutz E., Leutz A. A C/EBP β isoform recruits the SWI/SNF complex to activate myeloid genes. Mol. Cell. 1999;4:735–743. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80384-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann J.M., Moore L.B., Smith-Oliver T.A., Wilkison W.O., Willson T.M., Kliewer S.A. An antidiabetic thiazolidinedione is a high affinity ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:12953–12956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.12953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrke M., Lazar M.A. The many faces of PPARγ. Cell. 2005;123:993–999. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.S., Brutlag D.L., Liu J.S. An algorithm for finding protein–DNA binding sites with applications to chromatin-immunoprecipitation microarray experiments. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:835–839. doi: 10.1038/nbt717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDougald O.A., Mandrup S. Adipogenesis: Forces that tip the scales. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2002;13:5–11. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00517-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen L., Petersen R., Sørensen M.B., Jørgensen C., Hallenborg P., Pridal L., Fleckner J., Amri E.Z., Krieg P., Furstenberger G., et al. Adipocyte differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes is dependent on lipoxygenase activity during the initial stages of the differentiation process. Biochem. J. 2003;375:539–549. doi: 10.1042/bj20030503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahony S., Benos P.V. STAMP: A Web tool for exploring DNA-binding motif similarities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W253–W258. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margaritis T., Holstege F.C. Poised RNA polymerase II gives pause for thought. Cell. 2008;133:581–584. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsusue K., Peters J.M., Gonzalez F.J. PPARβ/δ potentiates PPARγ-stimulated adipocyte differentiation. FASEB J. 2004;18:1477–1479. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1944fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melillo R.M., Pierantoni G.M., Scala S., Battista S., Fedele M., Stella A., De Biasio M.C., Chiappetta G., Fidanza V., Condorelli G., et al. Critical role of the HMGI(Y) proteins in adipocytic cell growth and differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:2485–2495. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.7.2485-2495.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Nagai S., Shimizu C., Umetsu M., Taniguchi S., Endo M., Miyoshi H., Yoshioka N., Kubo M., Koike T. Identification of a functional peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor responsive element within the murine perilipin gene. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2346–2356. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy L., Tontonoz P., Alvarez J.G., Chen H., Evans R.M. Oxidized LDL regulates macrophage gene expression through ligand activation of PPARγ. Cell. 1998;93:229–240. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen R., Grontved L., Stunnenberg H.G., Mandrup S. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor subtype- and cell-type-specific activation of genomic target genes upon adenoviral transgene delivery. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:5698–5714. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02266-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto T.C., Lane M.D. Adipose development: From stem cell to adipocyte. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2005;40:229–242. doi: 10.1080/10409230591008189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer C.N.A., Hsu M.H., Griffin K.J., Johnson E.F. Novel sequence determinants in peroxisome proliferator signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:16114–16121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.27.16114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patsouris D., Mandard S., Voshol P.J., Escher P., Tan N.S., Havekes L.M., Koenig W., Marz W., Tafuri S., Wahli W., et al. PPARα governs glycerol metabolism. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;114:94–103. doi: 10.1172/JCI20468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen T.A., Kowenz-Leutz E., Leutz A., Nerlov C. Cooperation between C/EBPα TBP/TFIIB and SWI/SNF recruiting domains is required for adipocyte differentiation. Genes & Dev. 2001;15:3208–3216. doi: 10.1101/gad.209901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reshef L., Olswang Y., Cassuto H., Blum B., Croniger C.M., Kalhan S.C., Tilghman S.M., Hanson R.W. Glyceroneogenesis and the triglyceride/fatty acid cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:30413–30416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R300017200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen E.D., MacDougald O.A. Adipocyte differentiation from the inside out. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:885–896. doi: 10.1038/nrm2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross S.E., Erickson R.L., Gerin I., DeRose P.M., Bajnok L., Longo K.A., Misek D.E., Kuick R., Hanash S.M., Atkins K.B., et al. Microarray analyses during adipogenesis: Understanding the effects of Wnt signaling on adipogenesis and the roles of liver X receptor α in adipocyte metabolism. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:5989–5999. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.16.5989-5999.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salma N., Xiao H., Imbalzano A.N. Temporal recruitment of CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins to early and late adipogenic promoters in vivo. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2006;36:139–151. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Hon M., Evans R.M. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor δ, an integrator of transcriptional repression and nuclear receptor signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002;99:2613–2618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052707099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu M., Takeshita A., Tsukamoto T., Gonzalez F.J., Osumi T. Tissue-selective, bidirectional regulation of PEX11 α and perilipin genes through a common peroxisome proliferator response element. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:1313–1323. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.1313-1323.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeenk L., van Heeringen S.J., Koeppel M., Driel M.A., Bartels S.J.J., Akkers R.C., Denissov S., Stunnenberg H.G., Lohrum M. Characterization of genome-wide p53-binding sites upon stress response. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3639–3654. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultan M., Schulz M.H., Richard H., Magen A., Klingenhoff A., Scherf M., Seifert M., Borodina T., Soldatov A., Parkhomchuk D., et al. A global view of gene activity and alternative splicing by deep sequencing of the human transcriptome. Science. 2008;321:956–960. doi: 10.1126/science.1160342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple K.A., Cohen R.N., Wondisford S.R., Yu C., Deplewski D., Wondisford F.E. An intact DNA-binding domain is not required for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) binding and activation on some PPAR response elements. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:3529–3540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411422200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani R., Walther G., Hastie T. Estimating the number of clusters in a data set via the gap statistic. J. R. Stat. Soc. [Ser A] 2001;63:411–423. [Google Scholar]

- Tzameli I., Fang H., Ollero M., Shi H., Hamm J.K., Kievit P., Hollenberg A.N., Flier J.S. Regulated production of a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ ligand during an early phase of adipocyte differentiation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:36093–36102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405346200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehara Y., Miura S., von Eckardstein A., Abe S., Fujii A., Matsuo Y., Rust S., Lorkowski S., Assmann G., Yamada T., et al. Unsaturated fatty acids suppress the expression of the ATP-binding cassette transporter G1 (ABCG1) and ABCA1 genes via an LXR/RXR responsive element. Atherosclerosis. 2007;191:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Helden J. Regulatory sequence analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3593–3596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura A., Meissner A., Dillon C.P., McManus M., Sharp P.A., Van Parijs L., Jaenisch R., Jacks T. Cre-lox-regulated conditional RNA interference from transgenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004;101:10380–10385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403954101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Renes J., Bouwman F., Bunschoten A., Mariman E., Keijer J. Absence of an adipogenic effect of rosiglitazone on mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes: Increase of lipid catabolism and reduction of adipokine expression. Diabetologia. 2007;50:654–665. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0565-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Zang C., Rosenfeld J.A., Schones D.E., Barski A., Cuddapah S., Cui K., Roh T.Y., Peng W., Zhang M.Q., et al. Combinatorial patterns of histone acetylations and methylations in the human genome. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:897–903. doi: 10.1038/ng.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]