Abstract

The amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) plays a central pathophysiological role in Alzheimer’s disease, but little is known about the concentration and dynamics of this secreted peptide in the extracellular space of the human brain. We used intracerebral microdialysis to obtain serial brain interstitial fluid (ISF) samples in 18 patients who were undergoing invasive intracranial monitoring after acute brain injury. We found a strong positive correlation between changes in brain ISF Aβ concentrations and neurological status, with Aβ concentrations increasing as neurological status improved and falling when neurological status declined. Brain ISF Aβ concentrations were also lower when other cerebral physiological and metabolic abnormalities reflected depressed neuronal function. Such dynamics fit well with the hypothesis that neuronal activity regulates extracellular Aβ concentration.

Aβ is the principal constituent of the hallmark amyloid plaques found in Alzheimer’s disease and is the target of many potential treatments for the disease (1). However, little is known about the concentration and dynamics of this secreted peptide in the extracellular space of the human brain where these plaques form. In vitro and animal studies have shown that neuronal and synaptic activity dynamically regulate soluble extracellular Aβ concentrations (2–4). Whether similar regulation of Aβ levels occurs in the human brain is unknown.

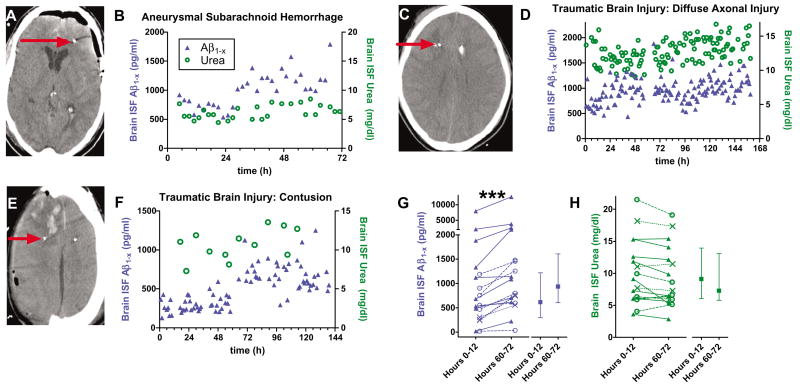

We used intracerebral microdialysis (5) to obtain serial brain interstitial fluid (ISF) samples in 18 intensive care unit (ICU) patients who had sustained acute brain injury and were undergoing invasive intracranial monitoring for clinical purposes. In all patients, Aβ1−x was detected in hourly or bihourly intracranial microdialysis samples. None had a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease or dementia, demonstrating that Aβ is a normal constituent of human brain extracellular fluid (6). The Aβ1−x enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) used detects Aβ species from amino acid 1 to amino acid 28 or greater (3, 7). There were rising trends in brain ISF Aβ concentrations over several hours to days in most patients, though the specific pattern of these trends was variable (Fig. 1, B, D, and F; Fig. 2B; and Fig. 4, A to D). Median brain ISF Aβ1−x at 60 to 72 hours was 59% higher than at 0 to 12 hours (Fig. 1G) (P = 0.0002, Wilcoxon signed rank test). Urea concentrations in the same samples, which control for the stability of the microdialysis catheter function (8), remained stable over the same time frame (Fig. 1H) (median 14% lower, P = 0.06, Wilcoxon signed rank test). Thus, the observed Aβ dynamics are likely to be of cerebral origin and not an artifact of the measurement procedure.

Fig. 1.

Aβ dynamics in human brain ISF assessed with intracerebral microdialysis after acute injury. (A, C, and E) Computerized tomography scans demonstrating location of microdialysis catheters; the radio-opaque gold tips of the catheters are indicated by red arrows. (B, D, and F) Brain ISF Aβ concentrations (blue triangles) measured hourly or bihourly in individual patients. Urea (green circles) was measured in several of the same microdialysis samples. Time (x axis) reflects interval from initiation of microdialysis. (G) Trends over time in brain ISF Aβ (***P = 0.0002, Wilcoxon signed rank test). (Left) Individual patient values. Closed triangles: traumatic brain injury patients with catheters placed in right frontal lobe white matter regions with no apparent focal injury (n = 9); x-symbols: traumatic brain injury patients with catheters placed in pericontusional brain tissue (n = 3); open circles: subarachnoid hemorrhage patients with catheters placed in right frontal lobe white matter (n = 6). (Right) Median, interquartile interval across all 18 patients. (H) Brain ISF urea was essentially stable. (Left) Individual patient values; (right) median, interquartile interval.

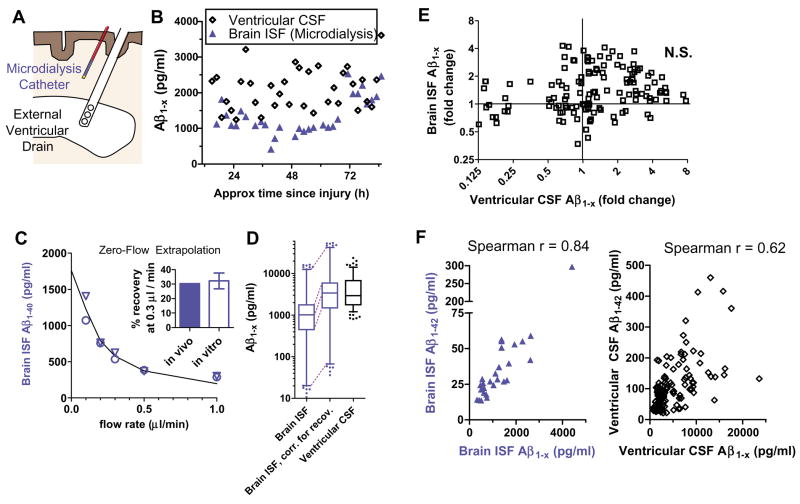

Fig. 2.

Brain ISF Aβ versus ventricular CSF Aβ. (A) Schematic demonstrating placement ofmicrodialysis catheters into subcortical white matter and external ventricular drains into the frontal horn of the lateral ventricle. (B) Simultaneous measurements of Aβ concentrations from brain ISF obtained by microdialysis and from ventricular CSF Aβ in a patient with traumatic brain injury. (C) Assessment of fractional recovery of Aβ during microdialysis. In vivo zeroflow extrapolation from one neurologically normal subject who had microdialysis performed for 24 hours after surgical clipping of an unruptured aneurysm. Triangles and circles represent independent measurements 12 hours apart. This method revealed ~30% recovery at a flow rate of 0.3 μl/min. In vitro recovery at 0.3 μl/min at room temperature (n = 10 catheters) was essentially identical (inset). Error bars (inset) are SEs. (D) Aβ concentrations in 140 paired samples from five patients in which both ventricular CSF and microdialysis measurements were possible. Box: median and interquartile range; whiskers: 5 to 95% confidence interval; circles: outliers. (E) Changes from initial values of Aβ over time in ventricular CSF versus changes from initial values over time in brain ISF. (F) Aβ1–42 concentrations compared with total Aβ1−x concentrations in brain ISF (left) and ventricular CSF (right). The correlation in brain ISF was stronger than in ventricular CSF (P = 0.029, difference test).

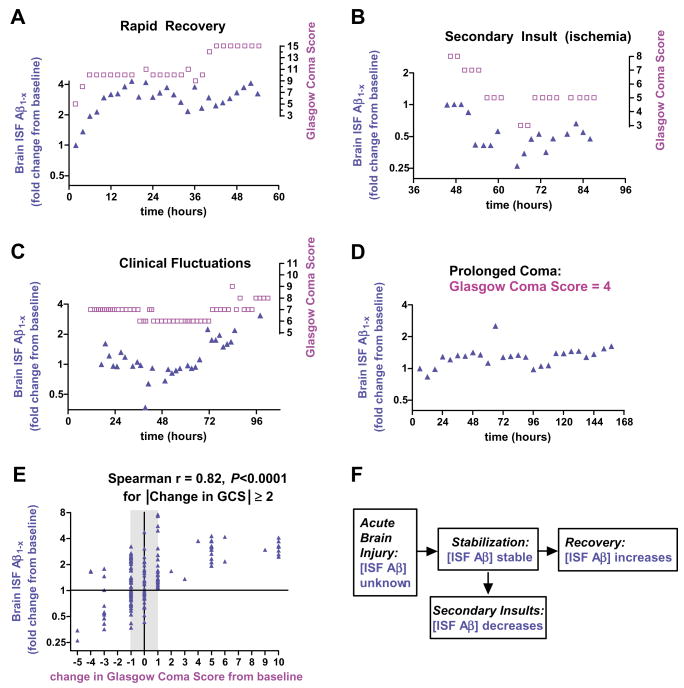

Fig. 4.

Brain ISF Aβ and neurological status. (A to D) Examples of the time course of changes in brain ISF Aβ concentrations and changes in neurological status, as reflected by Glasgow Coma Score (GCS). Aβ changes appear to track (A and B), and in some cases even precede (C), neurological status changes. (E) Correlation of change in brain ISF Aβ from baseline with changes in neurological status across 13 patients in which serial GCS measurements could be reliably obtained (n = 173 paired measurements). (F) Model of brain ISF Aβ dynamics in the setting of acute brain injury.

Aβ1−x concentrations were lower in microdialysate than in concomitantly sampled ventricular cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (Fig. 2, B and D). However, at the flow rate used (0.3 μl/min), the microdialysate is not in complete equilibrium with the surrounding extracellular space (5). To calculate the true brain extracellular concentrations, we used two methods to estimate the fractional recovery of Aβ under these conditions (Fig. 2C). First, we performed in vitro recovery experiments with known concentrations of Aβ. Second, we used in vivo zero-flow extrapolation, which relies on the principle that as flow rate approaches zero, equilibration across the membrane will approach completion (9). These two methods agreed well; recovery of Aβ was ~30% at 0.3 μl/min (Fig. 2C and figs. S1 and S2). After correction for this recovery, the concentrations in ventricular CSF and brain ISF were, on average, very similar (Fig. 2D). However, the range of concentrations in brain ISF was significantly wider (Fig. 2D), and the hour-by-hour dynamics of Aβ changes correlated poorly (Fig. 2, B and E).

The 42–amino acid form of Aβ (Aβ1–42) is of special interest; this form appears to have the greatest propensity to deposit into insoluble plaques, one of the pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease, as well as to aggregate into oligomeric Aβ species, reported to be especially neurotoxic (10–12). Current ELISA methods are not sensitive enough to measure Aβ1–42, Aβ1–40, and Aβ1−x in individual hourly or bihourly microdialysis samples, so 8-hour pools of microdialysis samples were combined for five patients. In these pooled samples, the Aβ1–40/Aβ1–42 ratio was 14 ± 5.2. Aβ1–42 concentrations were lower than Aβ1−x concentrations by a factor of 35 ± 12, and Aβ1–40 concentrations were lower than Aβ1−x concentrations by a factor of 2.5 ± 0.9. Thus, much of the Aβ measured by the Aβ1−x assay does not appear to be either Aβ1–40 or Aβ1–42. Brain ISF Aβ1–42 concentrations were consistently proportional to those of Aβ1−x (Fig. 2F). The relation was similar in ventricular CSF (Fig. 2F), though greater variability was observed. Thus, the observed trends in brain ISF Aβ1−x levels over time likely reflect changes in Aβ1–42 levels as well.

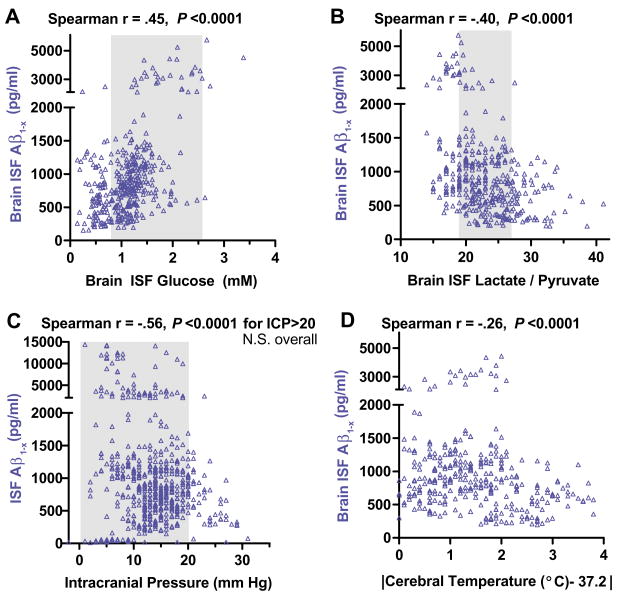

To address potential mechanisms underlying these dynamics, we compared brain ISF Aβ1−x concentrations from single samples with various microdialysis parameters and physiological measures obtained concurrently as part of clinical care in the intensive care unit (Fig. 3 and figs. S3 and S4). A positive correlation with brain ISF glucose (Fig. 3A), as well as negative correlations with brain ISF lactate/pyruvate ratio (Fig. 3B), elevated intracranial pressure (Fig. 3C), and extremes of cerebral temperature (Fig. 3D), were the most salient.

Fig. 3.

Correlations of brain ISF Aβ concentrations with other microdialysis parameters and physiological measures. (A) Brain ISF glucose versus brain ISF Aβ measured in the same microdialysis samples (n = 388 paired measurements). (B) Brain ISF lactate/pyruvate ratio versus brain ISF Aβ (n = 374). (C) Intracranial pressure (ICP) versus brain ISF Aβ (n = 565). (D) Absolute value of the difference between measured temperature cerebral temperature and normal cortical temperature, 37.2°C (27) versus brain ISF Aβ (n = 324). Each point represents a single paired measurement. Data are from 11 to 17 patients. Not all patients had all parameters measured at all time points (see supporting online material). Shaded regions represent mean ± 1 SD of estimated normal values (5, 27, 28).

Thus, brain ISF Aβ increased as overall physiology normalized. Indeed, in several patients, brain ISF Aβ concentrations tracked the patients, global neurological status, as assessed with the Glasgow Coma Score (Fig. 4, A to D); brain ISF Aβ concentrations rose as patients improved, remained stable in clinically stable patients, and appeared to decline when clinical status worsened. The Glasgow Coma Score (13) is a crude but reliable measure of neurological status in severely brain-injured patients that ranges from 3 (deeply comatose) to 15 (eyes open spontaneously, following commands, and speaking appropriately).

To quantify this relation across patients, we plotted change in brain ISF Aβ1−x from single samples versus change in Glasgow Coma Score (Fig. 4E). The clinical importance of a one-point change in the Glasgow Coma Score is often unclear, especially in critically injured, sedated patients. So for our primary analysis, we assessed changes in brain ISF Aβ only at times when Glasgow Coma Score had changed by two or more points from baseline (Fig. 4E). The correlation in this analysis was markedly strong (Spearman r = 0.82, P < 0.0001). The correlation, including one-point changes in Glasgow Coma Score, was still quite robust (Spearman r = 0.52, P < 0.0001). Such correlations were present in both traumatic brain injury patients and subarachnoid hemorrhage patients (r = 0.72, P < 0.0001 and r = 0.39, P = 0.0004, respectively; fig. S5). A much weaker correlation with neurological status was seen for ventricular CSF Aβ(r = 0.20, fig. S6).

What underlies this seemingly surprising association between local brain ISF Aβ levels and global neurological status (Fig. 4F)? Our findings in the human brain are consistent with previous results that indicate a direct causal relation between neuronal activity and extracellular Aβ in vitro (2) or brain ISF Aβ concentrations in mice (3, 4). From this perspective, the correlations between brain ISF Aβ concentrations and the other measured parameters fit well; low glucose and high lactate/pyruvate ratio indicative of abnormal brain metabolism, high intracranial pressure, and extremes of brain temperature all would likely result in impaired neuronal function (5). The absence of a correlation with glutamate levels, brain oxygenation, or cerebral perfusion pressure should not be taken as evidence against the neuronal activity hypothesis, because these parameters were rarely outside of their normal ranges in our patients (fig. S3).

Our findings complement the evidence from lesion studies in mice (14) and imaging studies in humans linking neuronal activity and Aβ deposition (15). However, based on prior results, the speed and magnitude of the dynamics seen here were unexpected. Smaller fluctuations in Aβ levels over hours to days have been observed in lumbar CSF from normal subjects (16).

Global neurological status was better correlated with brain ISF Aβ measurements in our patients than with ventricular CSF Aβ. This was surprising because ISF sampled by microdialysis comes from a relatively restricted area of the brain near the catheter, whereas ventricular CSF is derived from diffuse periventricular brain regions. On the other hand, many of the processes involved in acute brain injury and subsequent ICU care (e.g., sedation, anesthesia, etc.; fig. S7) likely affect neocortical neuronal and/or synaptic activity relatively homogeneously. We hypothesize that sampling from white matter adjacent to any cortical region gives a reliable indicator of global neuronal and/or synaptic function. Changes in global neuronal and/or synaptic function are in turn likely to be directly reflected in changes in the Glasgow Coma Score. In contrast, the relatively weak relation with ventricular CSF in these patients may indicate that factors other than neuronal/synaptic activity contribute much of the variance in ventricular CSF Aβ concentrations. The relation between brain ISF Aβ and CSF Aβ is clearly complex and requires further study. Lumbar CSF (16) may be derived from cortical ISF to a greater extent than ventricular CSF, and future studies will be required to address this issue because lumbar CSF was not obtained in these patients.

It is unlikely that there is a direct relation between the reported deposition of insoluble Aβ after traumatic brain injury (17–19) and the changes in brain ISF Aβ levels that we observed. Aβ deposits have been observed in a minority (approximately one-third) of subjects, whereas the rise in ISF Aβ over time was a nearly universal phenomenon (Fig. 1G). Thus, the relation between our findings and the reported epidemiological link between acute brain injury and the later development of Alzheimer’s disease (20, 21) is unclear.

Similarly, it is unlikely that these dynamics are related to axonal injury. If Aβ were being released into the extracellular space as a consequence of immediate axonal injury, we would have expected to see initially high brain ISF Aβ values, which then would have been expected to fall over time. This is the opposite of what we observed. We recognize that an increase of total tissue or intracellular Aβ levels (22, 23) would not have been detected, because microdialysis samples derive only from the extracellular space. Likewise, an early, transient rise in brain ISF Aβ concentrations would not have been detected, because catheters were implanted 12 to 48 hours after injury.

Our results provide direct information on the true extracellular fluid Aβ levels in the living human brain. To our knowledge, all but one of our patients had an acute brain injury, and none had dementia or Alzheimer’s disease. Nonetheless, this information is useful when considering whether levels of exogenous (10, 12, 24, 25) or endogenous Aβin experimental animals (26) are likely to be physiologically relevant in humans.

Supplementary Material

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/321/5893/1221/DC1

Methods

SOM Text

Figs. S1 to S7

References

References and Notes

- 1.Selkoe DJ. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1375. doi: 10.1172/JCI16783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kamenetz F, et al. Neuron. 2003;37:925. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cirrito JR, et al. Neuron. 2005;48:913. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cirrito JR, et al. Neuron. 2008;58:42. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hillered L, Vespa PM, Hovda DA. J Neurotrauma. 2005;22:3. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seubert P, et al. Nature. 1992;359:325. doi: 10.1038/359325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson-Wood K, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ronne-Engstrom E, et al. J Neurosurg. 2001;94:397. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.94.3.0397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutchinson PJ, et al. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:37. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.1.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walsh DM, et al. Nature. 2002;416:535. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lesne S, et al. Nature. 2006;440:352. doi: 10.1038/nature04533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shankar GM, et al. Nat Med. 2008;14:837. doi: 10.1038/nm1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teasdale G, Jennett B. Lancet. 1974;2:81. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lazarov O, Lee M, Peterson DA, Sisodia SS. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9785. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-22-09785.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buckner RL, et al. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7709. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2177-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bateman RJ, Wen G, Morris JC, Holtzman DM. Neurology. 2007;68:666. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000256043.50901.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts GW, et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57:419. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.4.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith DH, Chen XH, Iwata A, Graham DI. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:1072. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.98.5.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ikonomovic MD, et al. Exp Neurol. 2004;190:192. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jellinger KA. Curr Opin Neurol. 2004;17:719. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200412000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tesco G, et al. Neuron. 2007;54:721. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith DH, et al. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:1005. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65643-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abrahamson EE, et al. Exp Neurol. 2006;197:437. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klyubin I, et al. Nat Med. 2005;11:556. doi: 10.1038/nm1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cleary JP, et al. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:79. doi: 10.1038/nn1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Games D, Buttini M, Kobayashi D, Schenk D, Seubert P. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9:133. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-9s316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corbett R, Laptook A, Weatherall P. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:363. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199704000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reinstrup P, et al. Neurosurgery. 2000;47:701. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200009000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.We thank the participants and their families for their invaluable contributions. We appreciate the assistance of our neurosurgical colleagues for referring patients; M. Pluderi for placing several microdialysis catheters; and P. Bianchi, G. Brandi, M. Carbonara, U. Deledda, B. Hall, L. Magni, E. Milner, J. Sagar, and T. Zoerle for help collecting samples. Valuable discussions with R. Bateman, R. Bullock, J. Cirrito, R. Dacey, M. Diringer, L. Hillered, P. Hutchinson, J. Ladensen, N. Temkin, and W. Powers are acknowledged. We are grateful to Eli Lilly and Co. for providing the antibodies used in the Aβ ELISAs. This work was supported by NIH grant NS049237 (D.L.B.), a Burroughs Wellcome Career Award in the Biomedical Sciences (D.L.B.), NIH grant AG13956 (D.M.H.), and Cure Alzheimer’s Fund (D.M.H.).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/321/5893/1221/DC1

Methods

SOM Text

Figs. S1 to S7

References