Abstract

Background

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) are members of the TGF-β superfamily of proteins that have multiple functional roles in mammalian development. A role for BMP4 in adult vascular remodeling has recently been suggested. We evaluated the expression of Bmp4 during neointimal lesion development in vivo. We then assessed the role BMP4 signaling on SMC function during neointimal lesion development.

Materials and Methods

Heterozygous Bmp4lacZ/+ mice were used to evaluate in-vivo Bmp4 expression after carotid ligation. β-galactosidase (β-gal) activity was evaluated in histologic sections 1 to 14 days after carotid ligation and this was compared with control carotid arteries. The effects of recombinant human (rh) BMP4 on smooth muscle cell (SMC) migration and proliferation were evaluated using a rat aortic SMC line. We next assessed the effects of BMP4 signaling by over-expressing a constitutively active BMP receptor (BMPR-IA/Alk-3) using adenovirus-mediated gene transfer. SMC proliferation, migration, and apoptosis were evaluated in adenovirus transfected cells.

Results

Ligated carotid arteries expressed endothelium-specific β-gal staining after 1 day. Staining intensity increased at both 3 days and 1 week after ligation and remained stable at 2 weeks while no β-gal staining was observed in control vessels. Endothelial-specific expression of β-galactosidase was confirmed through positive staining for PECAM-1. When human recombinant BMP4 was added to cultured SMCs, it inhibited migration but did not affect cultured SMC proliferation. SMCs infected with adenovirus encoding for the active BMP receptor Alk-3 demonstrated dose-dependent receptor expression. Alk-3 over-expressing cells showed a dose-dependent decrease in proliferation and migration but no effect on apoptosis.

Conclusions

These results demonstrate that endothelial Bmp4 expression is responsive to flow alterations in-vivo, and furthermore, that activating the BMP signaling cascade results in decreased SMC proliferation and migration. This suggests that BMPs may counterbalance the effect of mitogen up-regulation observed during the development of neointimal hyperplasia.

Keywords: Bone morphogenetic Proteins, BMPs, shear stress, endothelial cell, smooth muscle cell, proliferation, migration, arterial remodeling, mouse

The endothelium of actively remodeling arteries is known to secrete factors that control medial SMC function [1]. The inward remodeling and neointimal development seen in diseased arteries is mediated by numerous factors that may stimulate or inhibit vascular smooth muscle cell migration and proliferation. One family of proteins thought to play an important role of vascular development and remodeling is the TGF-β superfamily of signaling molecules. The bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) are the largest subgroup of the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) protein superfamily, and over 20 BMP subfamily members have been identified in human and mouse [2]. Although they were named for their ability to induce ectopic cartilage and bone formation in vivo [3], these proteins have subsequently been shown to play key regulatory roles in a diverse set of developmental processes [4]. In embryonic cardiovascular development, BMPs are a key element in the induction of cardiac myogenesis [5]. BMP2 and BMP6 have been detected in adult human atherosclerotic arteries and are implicated in pathologic arterial calcification [6, 7]. BMPs act primarily through binding with two types of transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptors that are classified as type I (Alk-2, -3, and -6) and type II (BMPR-II, ActR-IIA and ActR-IIB). Activation of BMP receptors initiates phosphorylation of downstream signaling molecules known as receptor-regulated Smads [8]. BMP signaling is tightly controlled by extracellular inhibitory molecules including noggin, and through a series of positive and negative intracellular cofactors including the inhibitory Smads 6 and 7 [9].

BMP4 is one of the regulatory molecules in the TGF-β/BMP family. It functions at multiple stages of mammalian development and adult tissue remodeling including mesoderm induction, cartilage and bone induction, limb growth and differentiation, and fracture repair [10, 11]. Recently, cultured endothelial cells have been shown to express BMP4 in response to both cytokines and oscillatory shear stress [12]. Additionally, flow alterations in PTFE arterial grafts result in increased BMP4 mRNA levels that are accompanied by decreased expression of the extracellular BMP inhibitor noggin [13]. In this study, we evaluated the in vivo expression of BMP4 in mice after carotid ligation. We then evaluated the effects of BMP signaling on SMC proliferation, migration, and apoptosis using adenovirus-mediated delivery of a constitutively active BMP receptor. Our results suggest that BMP4 may counterbalance the effects of mitogens and chemoattractants that are activated during neointimal lesion formation.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Bmp4lacZneo heterozygous mice were generated and maintained as previously described [14]. The neor cassette was subsequently removed by crossing α-actin-Cre transgenic mice with Bmp4lacZneo heterozygous mice, and Bmp4lacZ heterozygous mice were backcrossed with outbred ICR mice to maintain the line.

Carotid ligation

A total of 30 male Bmp4lacZ/+ mice weighing 20 to 25 grams underwent unilateral left carotid ligation as previously described and under protocols approved by the Vanderbilt Animal Care and Use Committee [15]. General anesthesia was administered using ketamine 50-mg/kg and xylazine 10-mg/kg administered by intramuscular injection. Using sterile technique, a midline cervical incision was made and the left carotid bifurcation was exposed. The distal common carotid artery was ligated using 6-0 silk suture. The incision was then closed and animals were allowed to recover in a warm and dry environment. At time 0 (control) and at 1, 3, 7, and 14 days after carotid ligation, animals were euthanized by ketamine and xylazine overdose. Perfusion fixation was then carried out via cardiac puncture using fresh 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The right and left carotid arteries were dissected and harvested with care to avoid intimal damage. All protocols complied with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Animal Laboratory Resources, Commission on Life Sciences, National Research Council, Washington: National Academy Press, 1996).

Identification of β-gal expression in carotid specimens

After harvesting, carotid specimens were further fixed for 1 hour in 4% paraformaldehyde and stained using X-gal solution as previously described [16, 17]. Gross specimen photography was performed using a Zeiss Axiophot microscope. Carotid vessels with a granular blue staining pattern were counted as positive, while specimens with only mild, non-granular, diffuse blue staining or no staining were counted as negative for β-gal expression. Histologic examination was conducted using paraffin-embedded 5μm sections that were counter-stained with eosin for evaluation of X-gal staining.

Immunohistochemistry

After noting the intimal localization of β-gal positive cells, an additional 3 mice underwent carotid ligation and harvest at the 3 day post-ligation time point. Carotids were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 5-μm sections. Immunostaining was then performed using an antibody to the endothelial cell specific molecule PECAM-1 (BD Pharmingen; San Diego, CA) and a secondary antibody containing horseradish peroxidase (HRP). HRP positive cells were then identified by colorimetric methods with a Vectastain kit. (Vector laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

Adenoviral transfection of SMCs

Embryonic rat aortic SMC (A-10 cells; ATCC, Manassas, VA) were grown to 80% confluence then made quiescent by incubation in medium (DMEM) containing 0.5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for 24 hours. Cells were then exposed to various multiplicities of infection of a replication defective adenovirus encoding for Alk-3, a constitutively active form of the BMP receptor type 1A (BMPR-IA), tagged with hemagglutinin (HA) to allow for confirmation of protein expression (generously provided by M. Fujii, T. Imamura and K. Miyazono), or Ad.LacZ as a control [18]. High-titered stocks of recombinant viruses were grown in 293 cells and purified. Infection of cells using recombinant adenoviruses was performed at a multiplicity of infection up to 500 plaque forming units(pfu)/cell. After 24 more hours, cells were detached using trypsin, counted, and used for migration or proliferation studies as described below.

Confirmation of transgene expression was confirmed by immunofluorescence staining and western blotting. Briefly, 24 hours after transfection with Alk-3 or control adenovirus, cells in chamber slides were washed, fixed with ethanol, and incubated with rabbit anti-HA-antibody (Novus Biologicals, Inc, Littleton, CO) after appropriate blocking steps. Cells were then visualized by fluorescence microscopy after incubating in secondary FITC-labeled antibody and counterstaining with Hoechst nuclear stain. Transgene expression was also evaluated by western blotting. Using mouse anti-HA.11 antibody (Covance Research Products, Inc, Berkely, CA), western blots were performed on cell lysates of adenovirus-infected and control cells.

SMC Proliferation

Rat A-10 cells were grown in 24 well culture plates to 60% confluence and then made quiescent by incubation in medium containing 0.1% FBS. For experiments using recombinant human BMP4 (rhBMP4) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), cells were then incubated in DMEM containing 10% serum and rhBMP4 at 0, 50 or 200 μg/ml. 3H-thymidine incorporation was measured 24 hours later. For adenovirus transfection experiments, cells were transfected with Alk-3 adenovirus or control adenovirus at various concentrations. After 24 hours, cells were placed back into growth medium containing 10% FBS. Cells were then incubated with 1 μCi/ml for 24 hours and evaluated for 3H-thymidine incorporation by liquid scintillation counter. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

SMC Migration

SMC migration was evaluated by a modified Boyden chamber assay using 24-well plates with polycarbonate membranes containing 0.8 μm pores (Corning Life Sciences, Acton MA). Initially, we evaluated the effects of rhBMP4 on SMC migration. Rat A-10 cells were incubated in medium containing 0, 50, or 200 ng/ml hrBMP4 for one hour prior to placing in the top well of a chamber containing PDGF-BB (10 ng/ml) in the bottom well. Cells were allowed to migrate for 6 hours at 37°C. Membranes were then cut from their chambers, fixed, stained with Diff-Quik solution (Dade Behring Inc, Deerfield IL), and placed onto slides. Non-migrating cells were removed using a cotton-tipped swab. Migrated cells on the inferior surface of the membrane were counted under a light microscope at 200X magnification. We next evaluated the effects of Alk-3 expression on PDGF-induced SMC migration. Alk-3 transfected and control Ad.LacZ transfected SMCs were added to polycarbonate membranes (20,000 cells/membrane) above wells containing PDGF-BB (10 ng/ml). Membranes were then processed as above. The percent of migrated SMCs was counted in each of 3 separate wells for each treatment. All migration experiments were repeated at least 3 times to insure reproducibility.

Cell staining for apoptosis

Staining for apoptotic nuclei was performed using the Promega DeadEnd Colorimetric TUNEL staining kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were transfected with Alk-3 or control adenovirus as described above. After 24 hours, cells were fixed, made permeable, and then incubated in biotinylated nucleotide mix. Slides were then incubated in streptavidin-HRP followed by detection with DAB chromogen. Brown nuclei were counted as a percent of total nuclei in four separate 200X fields. Cells exposed to DNase solution were used as a positive control.

Statistics

For proliferation and migration experiments, differences were assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test and individual groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test with a significance assessed at the 95% confidence level.

Results

Bmp4lacZ is induced in endothelial cells following carotid ligation

In order to study the expression of Bmp4 during neointimal development in-vivo, left carotid arteries of Bmp4lacZ/+ mice were evaluated before and at 1, 3, 7, and 14 days after ligation. Gross evaluation of the ligated carotid vessels revealed a characteristic punctate staining pattern consistent with arterial β-gal activity. No staining was seen in 5 of 6 control specimens. (Figure 1A). The sixth specimen had mild, diffuse staining but this was less than in ligated vessels. Blue staining increased following carotid ligation and was most prominent at day 7 (Figure1B-D).

Figure 1.

Bmp4lacZ is induced after carotid ligation. Left carotid arteries from Bmp4lacZ/+ mice were harvested at ay 0 (control), and days 1, 3, and 7 post-ligation (B-D) and stained in X-ga solution. Punctate blue staining demonstrates Bmp4lacZ positive cells.

Histologic evaluation of ligated carotid segments demonstrated an endothelial-specific staining pattern with only sparse and infrequent staining of medial SMC (Figure 2). Staining intensity followed that observed on gross evaluation of specimens. We noted mild staining in 5 of 6 carotids at 1 day, moderate staining in 3 of 4 carotids at 3 days, intense staining in 7 of 7 carotids at 1 week, and moderate staining in 3 of 3 carotids at 14 days after ligation. No more than 3 positive SMC were identified in any one specimen, while complete absence of SMC staining was identified in most sections. Immunohistochemical staining for PECAM-1 demonstrated an intact endothelium without evidence of denudation or internal elastic membrane disruption. (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Bmp4lacZ is induced in intimal but not in medial or adventitial cells. Left carotid arteries from Bmp4lacZ/+ mice were harvested at day 0 (control) (A), and day 3, 7, and 14 after ligation (B-D) and stained in X-gal solution before being processed for histology. Sections were counterstained with nuclear fast red. Arrows indicate intimal cells

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry using anti-PECAM-1 antibody demonstrates intact endothelium in ligated carotid vessels. A) PECAM-1 antibody. B) PBS control. Arrows denote PECAM-1 positive cells in intima.

BMP receptor activation inhibits SMC proliferation

We initially evaluated whether direct addition of rhBMP4 protein to rat A-10 cells would inhibit proliferation. When rhBMP4 was added to proliferating rat A-10 cells, there was no effect on 3H-thymidine incorporation except at very high doses over 1000 ng/ml (data not shown). However, serum is known to contain extracellular inhibitors of BMP signaling including noggin and this may have affected our results. In order to bypass the effects of extracellular BMP inhibitors, we next evaluated the effects of BMP signaling by transfecting cells with a constitutively active form of BMPR-IA/Alk-3. We first evaluated our ability to express the receptor in rat A-10 cells in vitro. Our adenovirus construct included an HA tag and when rat A-10 cells were infected with 500 pfu/cell adenovirus encoding for Alk-3, immunofluorescence staining using an anti-HA antibody demonstrated intense staining in over 80% of the cells. Western blot analysis demonstrated a dose-dependent increase in HA, while there was no HA protein noted in cells transfected with a control virus. (Figure 4). SMC proliferation as assessed by 3H-thymidine incorporation was reduced to 88.8% following transfection with 100 pfu/cell Alk-3 adenovirus and to 46.9% following transfection with 500 pfu/cell (P<0.05). There was no effect on proliferation when cells were transfected with control LacZ adenovirus.(Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Adenoviral transfection with the constitutively active BMP type IA receptor. Hoechst stain demonstrates nuclear fluorescence in cells transfected with the Ad.LacZ (A) and Ad.Alk-3 (B). Anti-HA immunostaining for A10 cells transfected with the null vector Ad.LacZ (C) and Ad.Alk-3 (D). Anti-HA western blot demonstrates dose-responsive expression following transfection with the Ad.Alk-3 vector at 100 and 500 pfu/cell (E).

Figure 5.

Signaling via the BMP receptor Alk-3 inhibits SMC proliferation. Quiescent rat A10 cells were infected with 100 or 500 pfu of Ad.Alk-3 or control Ad.LacZ. After 24 hours, cells were detached using trypsin, counted and plated for evaluation of 3H-thymidine incorporation. Ad.Alk-3 transfected cells demonstrate a dose dependent decrease in 3H-thymidine incorporation compared to uninfected cells and control cells infected with Ad.LacZ. * P < 0.05 compared to LacZ control. Experiment performed twice with similar results.

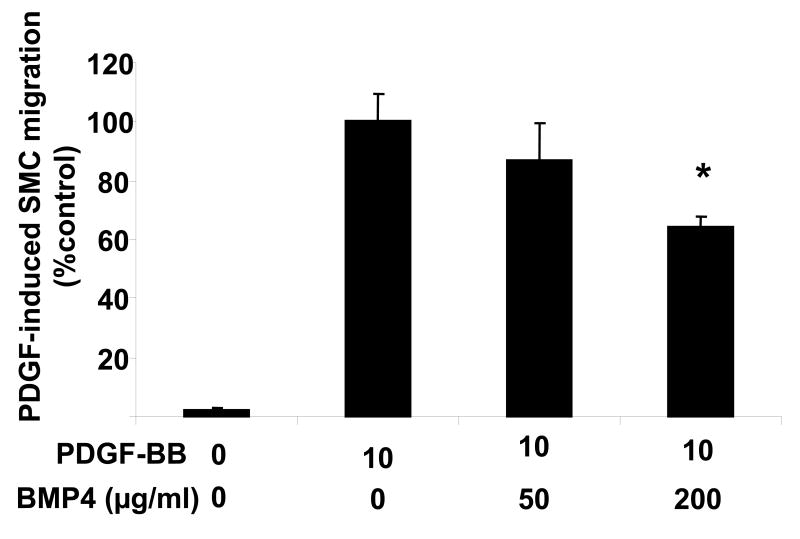

BMP receptor activation inhibits SMC migration

We next evaluated the effects of rhBMP4 on PDGF-induced SMC migration. This is because PDGF expression is sensitive to changes in flow, and PDGF is thought to play a major role in SMC migration during pathologic arterial remodeling [19, 20]. Rat A-10 cells exposed to BMP4 exhibited less PDGF-induced migration in a dose dependent manner. Cells exposed to 50 μg/ml rhBMP4 showed reduction in migration to 86% of control, while those exposed to 200 μg/ml showed a reduction to 64% of control (P<0.05).(Figure 6A)

Figure 6.

Rat aortic SMCs exposed to rhBMP4 show decreased migration. Rat A-10 cells were detached, counted, and then incubated in increasing concentrations of rhBMP4 for one hour prior to seeding in a modified Boyden chamber for evaluation of migration in response to PDGF placed in the lower well. There is decreased PDGF-induced SMC migration with the highest dose of rhBMP4 used. P<0.05 versus no BMP4. Results are shown from one of three separate experiments with similar results.

We next evaluated whether the effects of BMP4 on SMC migration could be reproduced by expression of active BMP receptor. Transfection of rat A10 cells with Ad.LacZ had no effect on PDGF-induced SMC migration; however, we observed a significant and dose-dependent reduction in SMC migration in cells infected with 10, 100, and 500 pfu/cell of the Alk-3 adenovirus to 49%, 23%, and 1% of control cells respectively (P<0.05). The effect of Alk-3 was unrelated to cellular viability as there was no effect of adenovirus infection on cell number (data not shown), or on apoptosis as assessed by TUNEL staining. (Figure 7) This suggests that flow-induced changes in endothelial BMP4 expression may work to counterbalance the effects of mitogens and chemo-attractants such as PDGF that contribute to pathologic arterial remodeling.

Figure 7.

Infection with Ad.Alk-3 inhibits PDGF-induced SMC migration. Quiescent rat A10 cells were infected with 100 or 500 pfu of Ad.Alk-3 or control Ad.LacZ. After 24 hours, cells were detached using trypsin, counted and plated for evaluation of PDGF-induced migration on transwell migration system. Ad.Alk-3 infected cells show a dose dependent decrease in migration toward 10-ng/ml PDGF in bottom well. (* P < 0.05 compared to lacZ control). Experiment performed three times with similar results.

Discussion

In the present study, we have demonstrated that endothelial Bmp4-lacZ expression is increased after carotid ligation in mice. We further show that BMP4 decreases SMC migration and that signaling via the BMP receptor Alk-3 limits proliferation and migration of SMCs. Because SMCs contribute to negative inward remodeling and intimal hyperplasia, increased BMP4 expression may serve to limit the pathologic effects of growth factors such as FGF and PDGF that promote SMC migration and proliferation. This suggests that increased expression of endothelial BMP4 may have protective effects during the development of intimal hyperplasia.

It is widely accepted that the endothelial lining of blood vessels can serve as a mechanical transducer that is capable of responding to changes in blood flow [21, 22]. Arterial changes occur through the release of vasoactive agents, growth factors, and chemoattractants from the endothelium [23]. These endothelium-derived factors then exert their effects on medial SMCs that undergo phenotypic changes. However, arterial remodeling is a complex and tightly regulated process that involves numerous counterbalancing factors, and long-term adaptation occurs through structural remodeling of the arterial wall. These changes are mediated by agents that influence smooth muscle cell migration, proliferation, apoptosis, and matrix synthesis or degradation.

One such family of agents that is thought to play a central role in structural remodeling of the vessel wall is the TGF-β superfamily of intercellular signaling proteins. Increased Bmp4 mRNA levels have been demonstrated in mouse aortic endothelial cells (MAEC) exposed to oscillatory, but not laminar, shear stress in vitro [12]. The mouse carotid ligation model is characterized by a sudden decrease in blood flow in the ligated carotid artery [24]. In mice, carotid ligation does not lead to thrombosis as in other species, but results in an oscillatory flow pattern that occurs with every cardiac cycle. While the physiologic relevance of this model to human pathology has been questioned [25], it has provided a reliable and reproducible system to evaluate the factors affecting intimal hyperplasia so long as appropriate precautions are used [26]. Carotid ligation induces proliferation of medial SMCs and results in extensive neointima formation in the presence of an endothelial lining. After 3-4 weeks, the luminal area is reduced to 80% due to negative remodeling and neointima formation [15]. We observed an increase in Bmp4lacZ expression in response to carotid ligation. These findings are consistent with the in vitro data suggesting that Bmp expression in mouse endothelial cells is responsive to oscillatory shear stress conditions.

A role for BMPs in graft neointimal development was convincingly demonstrated by Hsieh et al. who identified increased BMP4 levels in PTFE grafts exposed to high flow. BMP4 mRNA expression was slightly increased by day 1 but significantly increased at 7 days compared to normal flow grafts [13]. We observed a similar time course of Bmp4-lacZ induction in ligated mouse carotid arteries. Expression in our model was evident on day 1 and it peaked at day 7. It persisted for at least 14 days after ligation. Interestingly, Kumar et al have shown that medial SMC proliferation peaks at 5 days after ligation and decreases back to near baseline levels by 28 days, whereas intimal SMC proliferation peaks at 5 days and remains elevated until 14 days at which time it begins to decrease [15]. Our β-gal staining intensity was strongest at 7 days suggesting that BMP4 expression peaks at approximately the same time as SMC proliferation. This suggests that BMP4 may be increased in order counterbalance the effects of mitogens such as PDGF that are known to affect SMC proliferation during neointimal development. Further studies to determine the late expression patterns of Bmp4 are warranted, as are studies to relate Bmp4 expression to specific shear rates in the arterial wall.

Experiments regarding the effects of BMPs on SMC proliferation have yielded conflicting results that are possibly related to species differences or to differing experimental conditions. Using adenoviral expression methods, Nakaoka et al showed that BMP2 inhibited SMC proliferation and this resulted in decreased intimal hyperplasia in a rat carotid injury model [27]. Wong et al also demonstrated that BMP2 inhibits human VSMC proliferation and further showed that this occurred via the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21Cip1/Waf1[28]. SMCs exposed to rhBMP7 also exhibited decreased proliferation rates [29]. However, Willette et al failed to demonstrate anti-proliferative effects of BMP2 on vascular SMCs [30]. Most interestingly, BMP4 has been shown to induce opposite effects on proliferation in central versus peripheral pulmonary SMCs [31]. While BMPs share similarities in structure and function, it is also likely that BMP2, 4, and 7 activate different signaling programs that depend on a diverse set of intracellular signaling mechanisms. Our data using adenovirus-mediated over-expression of a constitutively active BMP receptor is consistent with an inhibitory effect of BMPs on SMC proliferation. This is in agreement with data from Nakaoka et al who demonstrated that adenovirus-mediated over expression of BMP2 inhibited SMC proliferation in the rat carotid injury model [27]. But we were unable to demonstrate an effect of rhBMP4 on SMC DNA synthesis and this may have been due to the use of human BMP4 protein on rat derived SMCs or to the presence of small amounts of BMP inhibitors, such as noggin, in our proliferation assays.

We did not see an effect of Alk-3 on SMC apoptosis in our rat aortic SMC line. It is possible, however, that longer expression times are needed to demonstrate apoptosis or that effects of Alk-3 over expression on apoptosis are dependent on the specific cell line studied. For example, Wong failed to demonstrate an effect of rhBMP2 on a human aortic SMC apoptosis after 24 hours [28], while Zhang et al observed increased apoptosis in pulmonary artery SMCs harvested from patients with primary pulmonary hypertension and treated with rhBMP2 for 48 hours [32]. Increased SMC apoptosis has recently been demonstrated in baboon neointimal cells exposed to rhBMP4 but only after 48 and 72 hours [13]. It is also possible that the effects of BMPs on SMC apoptosis are transduced through other signaling mechanisms that do not involve Alk-3. The known activation of signaling via the p21cip1/waf1 pathway involved in proliferation may also be involved in apoptosis and BMP2 has been shown to increase expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 [32]. This pathway may have been bypassed by over-expression of intracellular Alk-3. Efforts to evaluate the effects of BMPs on apoptosis in vivo will help to direct future studies.

With respect to the effect of BMPs on SMC migration, we were able to show that both exposure to BMP4 protein and activation of BMP signaling via Al k-3 significantly decreased PDGF-induced SMC migration. While previous studies have focused on the direct chemotactic effects of BMPs on vascular cells [30], we modeled our experiments on the ability of endothelial cells to produce multiple chemoattractant factors and the ability of SMCs to activate multiple signaling pathways simultaneously. Our data suggests that activating BMP signaling pathways in medial SMCs would inhibit migration and thus reduce pathologic arterial changes. It remains possible, however, that endothelial BMP secretion could induce migration out of the media and into the sub-endothelial space. Future experiments using cell-specific deletion of Bmp4 expression in mice will help to address many of these questions.

In the present study, we present in-vivo evidence that endothelial Bmp4 expression is induced by alterations in blood flow. Based on its inhibitory effects on SMC migration and proliferation in-vitro, we suggest that during the complex process of neointimal development, BMP4 may serve to counterbalance the proliferative and chemoattractant effects of factors such as FGF and PDGF that are also upregulated in vivo. BMPs share membrane bound receptors with other TGF-β family members and signal through the Smad family of intracellular signaling molecules. As such, our data adds a level of complexity to our understanding of TGF-β/BMP mediated arterial responses. It is likely that the final arterial response is related to the sum of proliferative and chemotactic stimuli of mitogens and the growth and migration inhibitory effects of factors such as the BMPs.

Figure 8.

Adenoviral expression of Ad.Alk-3 does not increase apoptosis. Rat A-10 cells transfected with Ad.Alk-3 or control adenovirus underwent evaluation for apoptosis after 24 hours using a Colorimetric TUNEL staining kit. Brown nuclei were counted as a percent of total nuclei in four separate 200X fields. One group of cells was exposed to DNase solution for use as a positive control. (P<0.05 compared with Ad.LacZ control.)

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a Mentored Clinical Scientist Development Award HL069926 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (RG) and grants from the Lifeline Foundation, and the William J. von Liebig Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kipshidze N, Dangas G, Tsapenko M, Moses J, Leon MB, Kutryk M, Serruys P. Role of the endothelium in modulating neointimal formation: Vasculoprotective approaches to attenuate restenosis after percutaneous coronary interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:733–739. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao X, Chen D. The BMP signaling and in vivo bone formation. Gene. 2005;357:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wozney JM, Rosen V, Celeste AJ, Mitsock LM, Whitters MJ, Kriz RW, Hewick RM, Wang EA. Novel regulators of bone formation: Molecular clones and activities. Science. 1988;242:1528–1534. doi: 10.1126/science.3201241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hogan BL. Bone morphogenetic proteins: multifunctional regulators of vertebrate development. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1580–1594. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.13.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schultheiss TM, Burch JBE, Lassar AB. A role for bone morphogenetic proteins in the induction of cardiac myogenesis. Genes Dev. 1997;11:451–462. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.4.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bostrom K, Watson KE, Horn S, Wortham C, Herman IM, Demer LL. Bone morphogenetic protein expression in human atherosclerotic lesions. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:1800–1809. doi: 10.1172/JCI116391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schluesener HJ, Meyermann R. Immunolocalization of BMP-6, a novel TGF-beta-related cytokine, in normal and atherosclerotic smooth muscle cells. Atherosclerosis. 1995;113:153–156. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(94)05438-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ten Dijke P. Bone morphogenetic protein signal transduction in bone. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22 1:S7–11. doi: 10.1185/030079906X80576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pogue R, Lyons K. In: BMP Signaling in the Cartilage Growth Plate Current Topics in Developmental Biology. Schatten GP, editor. Academic Press; 2006. pp. 1–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiao K, Kulessa H, Tompkins K, Zhou Y, Batts L, Baldwin HS, Hogan BL. An essential role of Bmp4 in the atrioventricular septation of the mouse heart. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2362–2367. doi: 10.1101/gad.1124803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shore EM, Xu M, Shah PB, Janoff HB, Hahn GV, Deardorff MA, Sovinsky L, Spinner NB, Zasloff MA, Wozney JM, Kaplan FS. The human bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP-4) gene: molecular structure and transcriptional regulation. Calcif Tissue Int. 1998;63:221–229. doi: 10.1007/s002239900518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sorescu GP, Sykes M, Weiss D, Platt MO, Saha A, Hwang J, Boyd N, Boo YC, Vega JD, Taylor WR, Jo H. Bone Morphogenic Protein 4 Produced in Endothelial Cells by Oscillatory Shear Stress Stimulates an Inflammatory Response. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31128–31135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300703200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsieh PCH, Kenagy RD, Mulvihill ER, Jeanette JP, Wang X, Chang CMC, Yao Z, Ruzzo WL, Justice S, Hudkins KL. Bone morphogenetic protein 4: Potential regulator of shear stress-induced graft neointimal atrophy. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawson KA, Dunn NR, Roelen BA, Zeinstra LM, Davis AM, Wright CV, Korving JP, Hogan BL. Bmp4 is required for the generation of primordial germ cells in the mouse embryo. Genes Dev. 1999;13:424–436. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.4.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar A, Lindner V. Remodeling with neointima formation in the mouse carotid artery after cessation of blood flow. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:2238–2244. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.10.2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guzman RJ, Lemarchand P, Crystal RG, Epstein SE, Finkel T. Efficient and selective adenovirus-mediated gene transfer into vascular neointima. Circulation. 1993;88:2838–2848. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.6.2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kume T, Deng KY, Winfrey V, Gould DB, Walter MA, Hogan BL. The forkhead/winged helix gene Mf1 is disrupted in the pleiotropic mouse mutation congenital hydrocephalus. Cell. 1998;93:985–996. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujii M, Takeda K, Imamura T, Aoki H, Sampath TK, Enomoto S, Kawabata M, Kato M, Ichijo H, Miyazono K. Roles of Bone Morphogenetic Protein Type I Receptors and Smad Proteins in Osteoblast and Chondroblast Differentiation. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:3801–3813. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.11.3801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malek AM, Gibbons GH, Dzau VJ, Izumo S. Fluid shear stress differentially modulates expression of genes encoding basic fibroblast growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor B chain in vascular endothelium. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:2013–2021. doi: 10.1172/JCI116796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dardik A, Yamashita A, Aziz F, Asada H, Sumpio BE. Shear stress-stimulated endothelial cells induce smooth muscle cell chemotaxis via platelet-derived growth factor-BB and interleukin-1alpha. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:321–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langille BL, F OD. Reductions in arterial diameter produced by chronic decreases in blood flow are endothelium-dependent. Science. 1986;231:405–407. doi: 10.1126/science.3941904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langille BL. Arterial remodeling: relation to hemodynamics. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1996;74:834–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gimbrone MA, Jr, Topper JN, Nagel T, Anderson KR, Garcia-Cardena G. Endothelial dysfunction, hemodynamic forces, and atherogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;902:230–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06318.x. discussion 239-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindner V, Fingerle J, Reidy MA. Mouse model of arterial injury. Circ Res. 1993;73:792–796. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.5.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korshunov VA, Berk BC. Flow-Induced Vascular Remodeling in the Mouse: A Model for Carotid Intima-Media Thickening. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:2185–2191. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000103120.06092.14.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myers DL, Liaw L. Improved Analysis of the Vascular Response to Arterial Ligation Using a Multivariate Approach. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:43–48. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63094-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakaoka T, Gonda K, Ogita T, Otawara-Hamamoto Y, Okabe F, Kira Y, Harii K, Miyazono K, Takuwa Y, Fujita T. Inhibition of rat vascular smooth muscle proliferation in vitro and in vivo by bone morphogenetic protein-2. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2824–2832. doi: 10.1172/JCI119830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong GA, Tang V, El-Sabeawy F, Weiss RH. BMP-2 inhibits proliferation of human aortic smooth muscle cells via p21Cip1/Waf1. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;284:E972–979. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00385.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dorai H, Vukicevic S, Sampath TK. Bone morphogenetic protein-7 (Osteogenic Protein-1) inhibits smooth muscle cell proliferation and stimulates the expression of markers that are characteristic of SMC phenotype in vitro. J Cell Physiol. 2000;184:37–45. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200007)184:1<37::AID-JCP4>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Willette RN, Gu JL, Lysko PG, Anderson KM, Minehart H, Yue TL. BMP-2 gene expression and effects on human vascular smooth muscle cells. J Vasc Res. 1999;36:120–125. doi: 10.1159/000025634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang X, Long L, Southwood M, Rudarakanchana N, Upton PD, Jeffery TK, Atkinson C, Chen H, Trembath RC, Morrell NW. Dysfunctional Smad signaling contributes to abnormal smooth muscle cell proliferation in familial pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Res. 2005;96:1053–1063. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000166926.54293.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang S, Fantozzi I, Tigno DD, Yi ES, Platoshyn O, Thistlethwaite PA, Kriett JM, Yung G, Rubin LJ, Yuan JX. Bone morphogenetic proteins induce apoptosis in human pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L740–754. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00284.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]