Abstract

A Thr (or Ser) residue on the I-helix is a highly conserved structural feature of cytochrome P450 enzymes. It is believed to be indispensable as a proton delivery shuttle in the oxygen activation process. Previous work showed that P450cin (CYP176A1), which contains an Asn instead of the conserved Thr, is fully functional in the catalytic oxidation of cineole [Hawkes, D.B. et al. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 27725–27732]. To determine whether the substitution of Asn for Thr is specific or general, the conserved Thr252 in P450cam (CYP101) was mutated to generate the T252N, T252N/V253T, and T252A mutants. Steady-state kinetic analysis of the oxidation of camphor by these mutants indicated that the T252N and T252N/V253T mutants have comparable turnover numbers but higher Km values relative to the wild-type enzyme. Spectroscopic binding assays indicate that the higher Km values reflect a decrease in the camphor binding affinity. Non-productive H2O2 generation was negligible with the T252N and T252N/V253T mutants, but, as previously observed, was dominant in the T252A mutant. Our results, and a structure model based on the crystal structures of the ferrous dioxygen complexes of P450cam and its T252A mutant, suggest that Asn252 can stabilize the ferric hydroperoxy intermediate, preventing premature release of H2O2 and enabling addition of the second proton to the distal oxygen to generate the catalytic ferryl species.

The cytochrome P450 (CYP or P450) family of enzymes is involved in oxidative metabolism of a wide range of endo- and exogenous chemicals [1]. P450cam (CYP101) from Pseudomonas putida, the structurally and biochemically best characterized P450 enzyme [2], catalyzes the regio- and stereospecific hydroxylation of camphor to 5-exo-hydroxycamphor. As first established for P450cam, the general P450 catalytic cycle involves (a) substrate binding, (b) reduction of the iron from the ferric to the ferrous state, (c) oxygen binding to form the ferrous dioxy (FeII-O2) complex, (d) uptake of a second electron to give a ferric peroxy anion (FeIII-O2−) intermediate, (e) protonation to give the ferric hydroperoxy (FeIII-OOH) intermediate, (f) protonation of the distal oxygen in this complex with concurrent cleavage of the oxygen-oxygen bond, forming the activated (ferryl) oxidizing species, (g) insertion of the ferryl oxygen into the substrate, and (h) product release [2]. Uncoupled turnover, in which reducing equivalents are employed to reduce molecular oxygen to superoxide or H2O2 can occur by dissociation of the ligand from the ferrous dioxy or ferric hydroperoxide intermediates, respectively. Uncoupled turnover can also involve reduction of the ferryl catalytic species to water by the further uptake of electrons from the electron donor partner. The ferric hydroperoxy intermediate (step e) thus sits at an important branch point of P450 catalysis: dissociation of the hydroperoxy group results in uncoupled H2O2 production, whereas protonation and oxygen-oxygen bond cleavage leads to the productive oxidative pathway [3].

An acid-alcohol side-chain pair, typically an Asp and Thr, is thought in most P450 enzymes to be a requirement for productive dioxygen activation in P450 catalysis [3]. The crystal structures of ferrous camphor- and CO-bound P450cam suggest that Thr252 is a key catalytic residue. This inference is substantiated by the fact that mutation of Thr252 to an Ala, Val, or Leu produces enzymes in which substrate hydroxylation is highly uncoupled from electron transfer [4–7], whereas replacement by a Ser yields a catalytically active enzyme [6]. In one instance is the conserved Thr replaced by a non-hydrogen bonding moiety. In P450eryF, Ala245 replaces what should normally be the conserved Thr [8]. However, the crystal structure of this protein complexed with its normal substrate indicates that the role of the hydroxyl in the normally conserved Thr is satisfied by a hydroxyl group on the substrate itself. This makes P450eryF highly substrate specific, but reintroduction of the Thr in the A245T mutant restores catalytic activity with a variety of other substrate [9]. The critical Thr could serve as a proton for conversion of the ferric hydroperoxy anion into the ferric hydroperoxy intermediate, or could stabilize the ferric hydroperoxy intermediate by a hydrogen bonding interaction, or could help in the placement of a water molecule that in turn serves as a proton source in the dioxygen bond scission step (Fig. 1) [3].

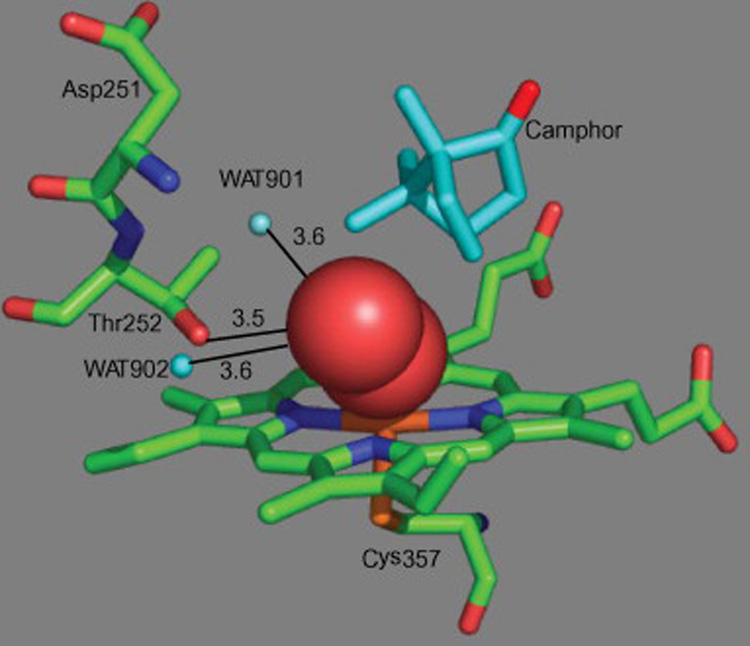

Fig. 1.

View of the O2 complex in the active site of P450cam. The figure was made from the high-resolution X-ray crystal structure (PDB entry: 1DZ8) using the program PYMOL [2]. The red balls represent the dioxygen intermediate.

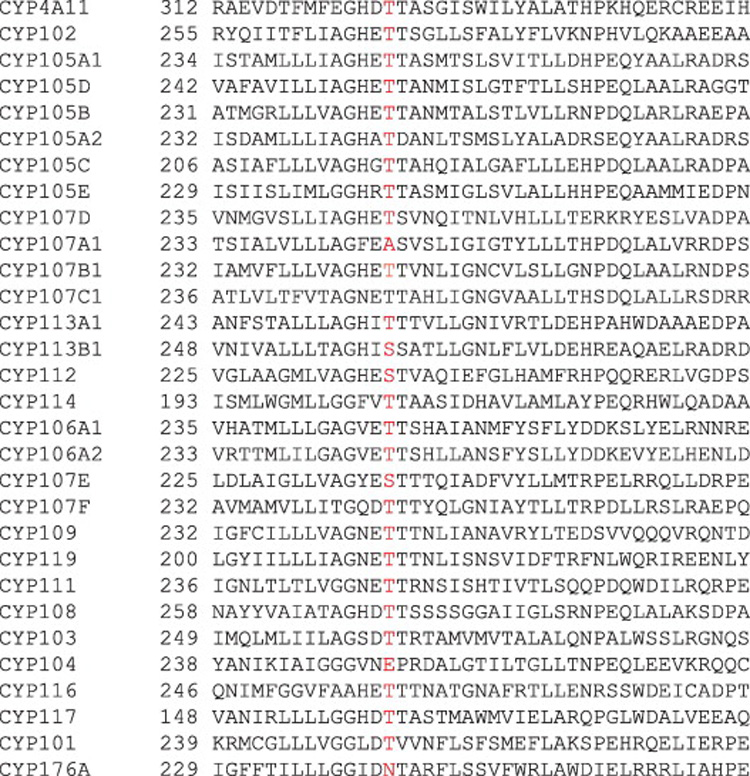

CYP176A (P450cin) from Citrobacter braakii, an organism that can grow on 1,8-cineole as its sole source of carbon and energy [10], is exceptional in that it does not retain the conserved, catalytically important hydroxyl residue (Thr or Ser) in the distal I helix (Fig. 2). The crystal structure of CYP176A suggested that Asn242, the corresponding residue in the I-helix, forms a hydrogen bond with 1,8-cineole [11]. It has also been suggested that this residue, which is part of a stable hydrogen bonding network, substitutes for the conserved Thr and helps to deliver the protons required for oxygen activation [11]. Asn242 may therefore fulfill a dual function by both anchoring the substrate and assisting in proton delivery [11]. In this investigation, we have examined whether the role of Asn in P450cin is specific to that enzyme or is a substitution that is more generally effective in maintaining the P450 catalytic function.

Fig. 2.

Sequence alignment of several P450 enzymes in the vicinity of the highly conserved Thr residue.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and enzymes

(1R)-(+)-Camphor, sodium dithionite, and NADH were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) or Aldrich Chemical Co. (Milwaukee, WI). Other chemicals were of the highest commercially available grade. Recombinant putidaredoxin (Pd) and putidaredoxin reductase (PdR) heterologously expressed in E. coli were kindly provided by Dr. Yongying Jiang (UCSF).

Construction of expression plasmids for P450cam mutants

The putative T252 mutants were constructed from the wild-type pBL(CYP101) vector using Quick-Change mutagenesis (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) with the following primers; 5’-GGCCTGGATAACGTGGTCAATTTC-3’, 5’- GGCCTGGATAACACGGTCAATTTC-3’, and 5’- GGCCTGGATGCGGTGGTCAATTTC-3’ (only forward primers shown, the underlined bases denote mutated codons). The change in nucleotides was confirmed by sequencing. The open reading frames (ORF) for P450cam mutants including a 6 × His carboxyl-terminal tag were cloned into the pCW(Ori+) expression vector using the NdeI and XbaI restriction sites as previously described [12].

Expression and purification

Expression and purification of P450cam mutants were carried out as previously described with some modifications [13]. The E. coli strains transformed with pCW(Ori+) vectors were inoculated into TB medium containing 100 µg/ml ampicillin and 1.0 mM IPTG. The expression cultures were grown in 1 liter Fernbach flasks at 37 °C for 3 h and then at 24 °C with shaking at 200 rpm for 24 h. The solid camphor was added to the culture 1 h before harvest (200 mg/liter). The soluble proteins were separated by ultracentrifugation and purified using the Ni2+-nitrilotriacetate and DEAE Sepharose columns as described previously [14,15]. The fractions containing the 47 kDa protein were pooled and dialyzed with 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4).

Enzyme assays

Camphor oxidation by wild-type P450cam and its mutants was determined using the P450/Pd/PdR system [16]. The reaction mixture contained 200 pmol purified P450 enzyme, 1 nmol Pd, and 200 pmol PdR, in 0.50 ml of 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), along with a specified amount of the substrate. The reactions were initiated by the addition of 50 µl of 10 mM NADH. Incubations were generally done for 10–30 min at 37 °C and terminated by addition of 0.5 ml of CH2Cl2, followed by vortex mixing and centrifugation. The lower organic layer was transferred to a clean tube and analyzed by GC-MS

GC-MS analyses of camphor and its metabolite

Analyses were performed on an Agilent 6850 gas chromatograph coupled to an Agilent 5973 Network Mass Selective Detector in the flame ionization mode as previously described [17]. Helium was used as the carrier gas. The GC was equipped with an HP-5MS cross-linked 5% PH ME Siloxane capillary column (30 m, 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 µm film thickness). The temperature program was 70 °C for 1 min and then 70–280 °C at 15 °C/min or 70 °C for 5 min, 70–160 °C at 5 °C/min, and then 160–280 °C at 20 °C/min. The temperatures were 250 °C for the injection port and 280 °C for the detector. A sample of 3 µl was injected in a 10:1 split ratio onto the column. Identification of camphor and 5-exo-hydroxycamphor was done by co-chromatographic and mass spectrometric comparison with authentic standards.

NADH oxidation and H2O2 formation

NADH oxidation rates for P450cam enzymes were determined in steady state kinetic experiments using the P450/Pd/PdR system in a 1:5:1 ratio, respectively. The P450/Pd/PdR system was preincubated for 5 min at 37 °C in the presence of camphor (2 mM). The reactions were initiated by addition of 10 µl of 10 mM NADH. The decrease of A340 was monitored and the rates were calculated using Δε340 = 6.22 mM−1 cm−1.

H2O2 formation was measured as described elsewhere [18]. Reactions (500 µl) were initiated by adding the NADH and terminated by adding 1 ml of cold CF3CO2H (3%, w/v) after 60 s. H2O2 was determined spectrophotometrically by reaction with ferroammonium sulfate and KSCN as described [19].

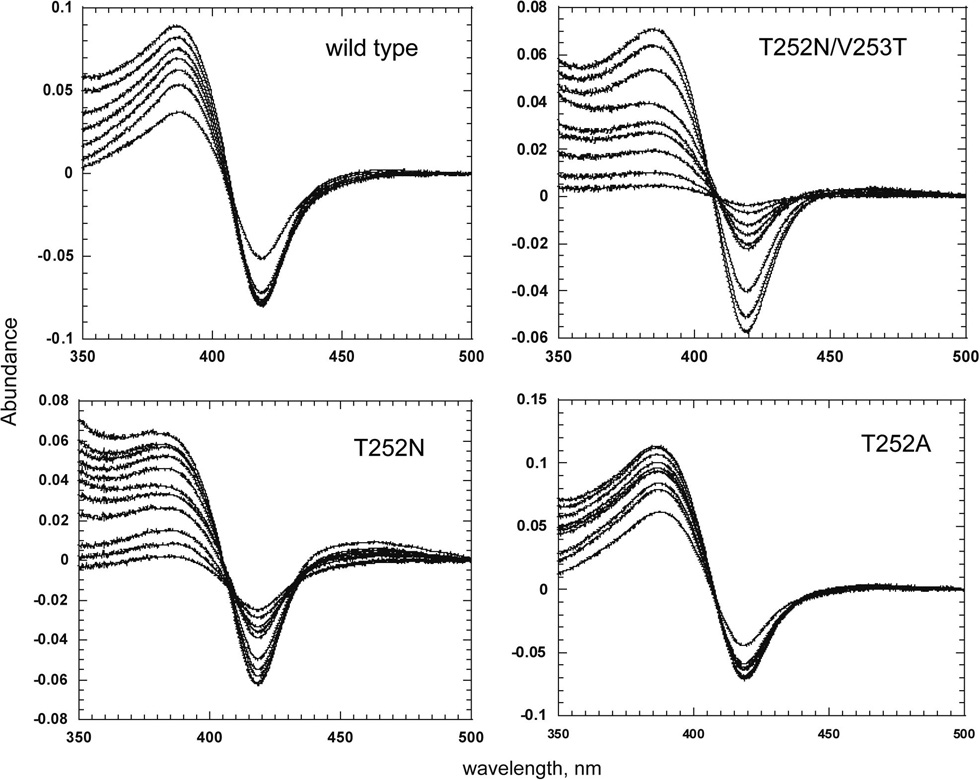

Spectral binding titrations

The substrate binding affinities of wild-type and mutant P450cam enzymes were obtained as previously described with some modifications [20]. Briefly, purified P450cam enzymes were diluted to 1 µM in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and the solutions were then partitioned into two glass cuvettes. The spectroscopic changes (350 – 500 nm) associated with sequential additions of camphor were recorded on a CARY Varian spectrophotometer. The difference in absorbance between the wavelength maximum (390 nm) and minimum (420 nm) was plotted versus the substrate concentration to estimate Kd.

Molecular modeling

Insight II software program (Accelrys Inc, San Diego, CA) was used for the molecular modeling and structural analysis using the crystal coordinates of the ferrous dioxygen complexes of wild-type P450cam and its T252A mutant (accession codes 2A1M and 2A1O in the Protein Data Bank) (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/).

Results

Expression and purification of P450cam mutants

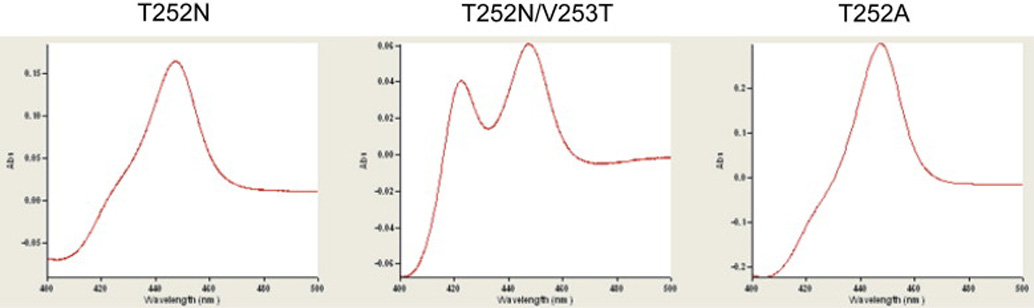

P450cam mutant clones in which Thr252 was replaced by an Asn (T252N) or Ala (T252A) were constructed by site-directed mutagenesis and verified by sequencing. In addition, the amino acid sequence alignment (Fig. 2) shows that Thr243 is adjacent to Asn242 on the I-helix of P450cin. Although the X-ray crystal structure indicates that Thr243 does not project into the active site [11], we have explored a possible catalytic role for the consecutive Asn242-Thr243 sequence by introducing the corresponding sequence into P450cam in a T252N/V253T double mutant. The P450cam mutants were expressed at high levels in E. coli cells and the purified proteins were obtained in good yields (Table 1). There was essentially no 420 nm species in the ferrous-CO spectra of the purified T252N and T252A proteins (Fig. 3), but the presence of both 450 and 420 nm peaks in the T252N/V253T double mutant suggests that some conformational instability is introduced by the double substitution.

Table 1.

Expression of P450cammutant enzymes

| Whole cells | Final purified enzyme | |

|---|---|---|

| P450 | ||

| nmol per liter culture | nmol | |

| Wild-typea | 255 | |

| T252N | 540 | 423 |

| T252N/V253T | 110 | 63 |

| T252A | 2300 | 515 |

Wild-type P450camwas previously reported [17]

Fig. 3.

Spectra of the recombinant, purified P450cam T252N, T252N/V253T, and T252A proteins in the ferrous-CO complexed state.

Camphor hydroxylation activities of wild-type P450cam and mutants

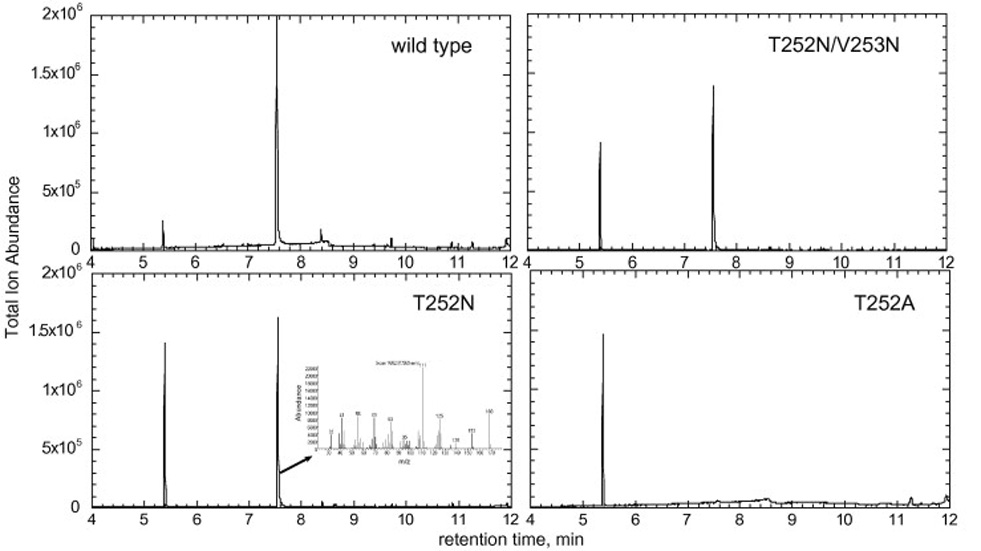

Camphor hydroxylation assays with the wild-type and mutant P450cam proteins were performed using a reconstituted system with P450, Pd and PdR in a 1:5:1 ratio, respectively. The production of 5-exo-hydroxycamphor was established by GC-MS comparison with an authentic standard (Fig. 4). The T252N and T252N/V253T mutants, like the wild-type protein, showed strong camphor hydroxylation activities. However, as previously reported [6], the camphor hydroxylation activity of the T252A mutant was negligible (Fig. 4). These results suggest that the function of the highly conserved Thr residue can be satisfied by an asparagine.

Fig. 4.

GC-MS total ion traces of the camphor oxidation products produced by P450cam and its mutants. The mass spectrum of the product at 7.57 min produced by the T252N mutant is shown in the inset of the appropriate panel.

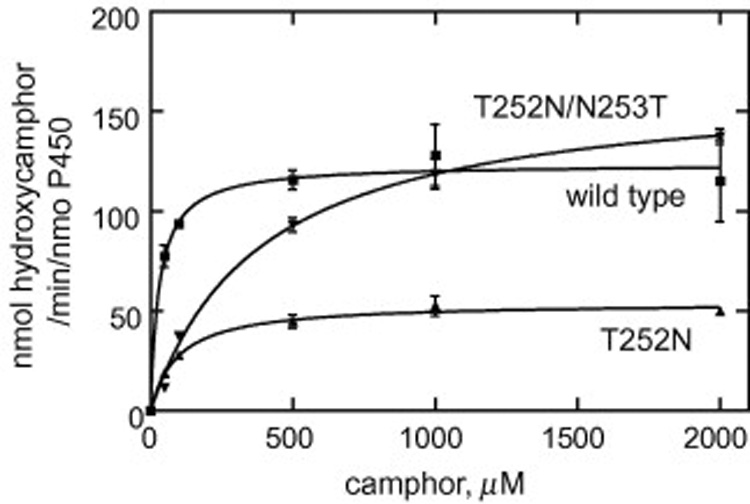

Steady-state kinetics of P450cam wild-type and mutants

In order to more precisely evaluate the changes of enzymatic activity associated with the mutations, steady-state kinetic parameters were obtained by measuring the final reaction product (5-exo-hydroxycamphor). The T252N mutant showed a high turnover number although it was lower than that of the wild-type, while that of the T252N/V253T mutant was similar to that of the wild-type (Fig. 5and Table 2). However, the T252N and T252N/V253T mutants had increased Km values for camphor hydroxylation. This result suggests that the Thr252 mutation influences the Km parameters by decreasing the substrate binding or access.

Fig. 5.

Steady-state kinetics of camphor hydroxylation by wild-type P450cam and its T252 mutants. Each point represents the mean ± SD of a triplicate assay. The kinetic parameters estimated from these plots are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Steady-state kinetic parameters for camphor hydroxylation of P450cam mutant enzymes

| P450 | kcat (min−1) | Km(µM) |

|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 124 ± 6 | 30 ± 10 |

| T252N | 54 ± 2 | 96 ± 15 |

| T252N/V253T | 165 ± 7 | 388 ±51 |

| T252A | NDa | NDa |

Not detected

Coupling efficiency of P450cam wild-type and mutants

The rates of H2O2 formation and NADH consumption were measured to calculate the coupling efficiency of the wild-type and P450cam mutants. In our assays, the wild-type P450cam exhibited a coupling efficiency of 71% as judged by comparison of NADH consumption and 5-hydroxycamphor formation (Table 3). The T252N and T252N/V253T mutants had coupling efficiencies of 42% and 38%, respectively (Table 3). With none of these three enzymes was the formation of H2O2 detected, which suggests that the uncoupling occurred after oxygen activation to produce water. The T252A mutant, in contrast, exhibited a high rate of NADH consumption and the production of both H2O2 and H2O, but no camphor hydroxylation. These results indicate that the asparagine substitution allowed the enzyme to oxidize the substrate with an efficiency and rate approaching that of the wild-type enzyme.

Table 3.

NADH oxidation, and H2O2 formation with wild-type P450camand its mutants.

| P450 | Camphor hydroxylation | NADH consumption | H2O2 formation | H2O formationa | Coupling efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| min−1 | min−1 | min−1 | min−1 | % | |

| Wild-type | 206 | 289 | 0 | 42 | 71 |

| T252N | 92 | 216 | 0 | 62 | 42 |

| T252N/V253T | 132 | 343 | 0 | 106 | 38 |

| T252A | 0 | 427 | 33 | 197 | 0 |

H2O formation was determined by calculating the difference between total NADH utilized and the sum of H2O2 formation and products produced and then dividing by 2 [22].

Substrate binding affinities of wild-type P450cam and mutants

The binding affinities of P450cam and its mutants for camphor were estimated spectrophotometrically (Table 4). Titration of all the enzymes with camphor gave rise to a typical Type I binding spectrum, consistent with displacement of the water coordinated to the heme iron in the resting enzyme (Fig. 6). Wild-type P450cam showed the tightest binding of camphor (Kd = 1.8 µM). In contrast, the replacement of Thr252 by an Asn mutation decreased the substrate binding affinities of the T252N and T52N/V253T to Kd = 34 and 12 µM, respectively. The increased Km values for camphor oxidation are therefore, at least in part, due to the decreased affinities of the mutants for the substrate. The substrate binding affinity of the T252A mutant, which essentially does not oxidize camphor, was similar to that of the wild-type enzyme. The inability of this mutant to oxidize camphor thus results from a mechanism independent of its substrate binding ability.

Table 4.

Estimated substrate binding affinities to P450cam

| Kd(µM) | |

|---|---|

| P450cam | |

| Camphor | |

| Wild-type | 1.8 ± 0.1 |

| T252N | 34 ± 2 |

| T252N/V253T | 12 ± 1 |

| T252A | 2.9 ± 0.2 |

Fig. 6.

Difference spectra showing the binding of camphor to the T252N, T252N/V253T and T252A mutants of P450cam.

Discussion

The interesting finding that the highly conserved I-helix Thr (or Ser) is replaced in P450cin by an Asn reopens the question of the specific role and requirements for the functional group at this position. It is significant in this context that P450cin is very closely related to the prototypical enzyme, P450cam, not only in structure but also with respect to the size, shape, and chemical composition of cineol and camphor, their respective substrates [11]. Although the crystal structure of P450cin complexed with cineol has been determined, it does not fully explain how P450cin compensates for the missing Thr hydroxyl group. As noted in the introduction, several roles can be envisioned for the conserved distal Thr [11]. The finding that replacement of the hydroxyl of Thr252 with a methoxy group in P450cam yields an active, coupled enzyme indicates that the role of the hydroxyl is likely to be as a proton acceptor rather than proton donor [7].

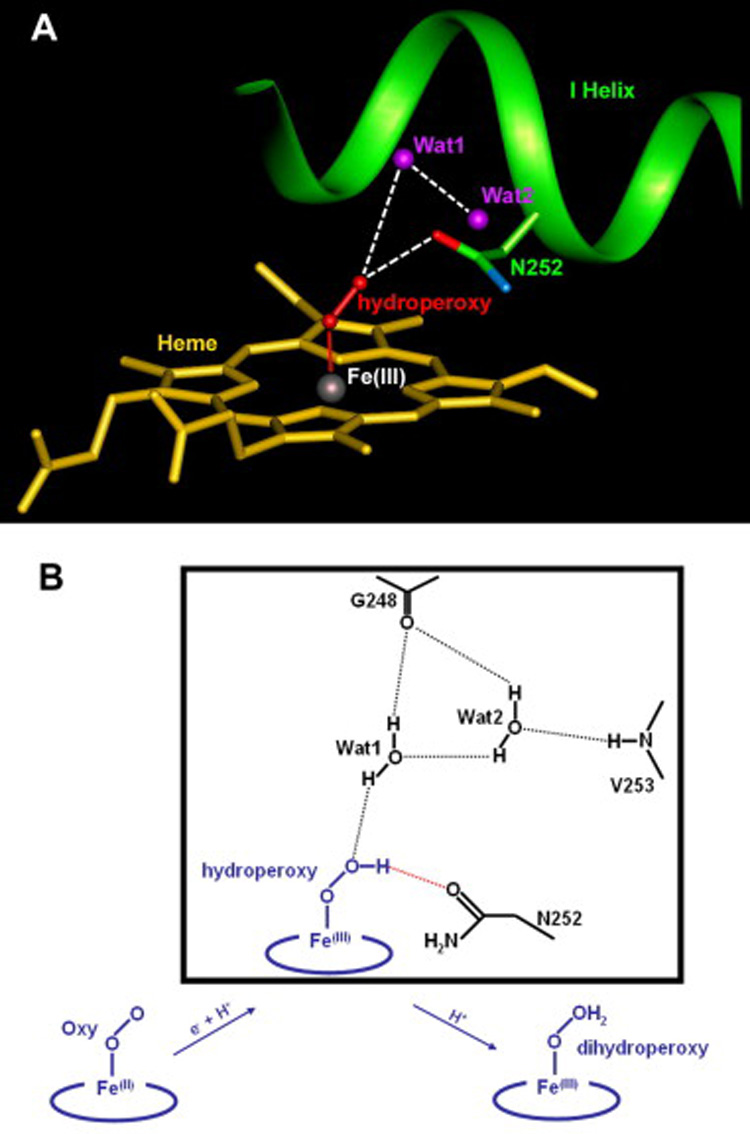

To investigate the molecular basis for the retention of coupling efficiency in the T252N mutant, we have carried out a modeling study using the crystal structures of the ferrous dioxygen complexes of wild-type P450cam and its T252A mutant [2, 21]. Proton transfer is required for scission of the iron-bound dioxygen bond to give the Fe(IV)=O hydroxylating species and it was proposed that the required protons are delivered by a proton shuttle involving a hydrogen-bonding network that includes two water molecules [3]. In the T252A mutant, the consumption of NADH was funneled into the uncoupled production of peroxide and water rather than substrate hydroxylation. However, the two catalytic water molecules are retained in the crystal structure of the T252A mutant, which suggests that the role of Thr252 is not to hold the active site water molecules in place, and that uncoupling does not result from disordering of the two active site water molecules [21]. The early finding that the Thr252 side chain hydroxyl group can be replaced by a methoxy group without a significant change in the coupling efficiency indicates that Thr252 does not serve as a hydrogen bond or proton donor in the dioxygen activation process [7]. It is therefore likely that Thr252 serves as a hydrogen bond acceptor from the ferric hydroperoxy intermediate. This hydrogen bond stabilizes the intermediate until a second proton can be delivered to the terminal oxygen of the hydroperoxide ligand, triggering heterolytic dioxygen bond scission to generate the active hydroxylating species [21]. Our results with the T252N mutant indicate that Asn252 can satisfy this hydrogen bond acceptor function as well as the normal threonine residue. In our model of the T252N mutant in complex with the iron-bound dioxygen, the oxygen atom of the Asn252 side chain can readily assume a conformation that places it in the appropriate position to accept a hydrogen bond from the iron-bound hydroperoxide ligand (Fig. 7). Asn252 cannot hydrogen bond to the two catalytic water molecules in the model structure, but these two water molecules would presumably remain in their usual positions, as found in the T252A mutant. In contrast to the T252A mutant, however, the T252N mutant retains high substrate hydroxylation activity because the Asn252 residue, unlike Ala252, interacts directly with hydroperoxy intermediate and stabilizes it. This enables the T252N to form the normal ferryl hydroxylating species, whereas the absence of this stabilization of the hydroperoxide intermediate by the T252A mutation results in dissocidation of H2O2 from the enzyme and uncoupled turnover.

Fig. 7.

Molecular basis for retention of the substrate oxidizing activity of the T252N mutant. (A) Hypothetical model of the T252N mutant with the iron-bound dioxygen. Wat1 and Wat2 are the catalytic water molecules, which serve as a proton shuttle for the delivery of protons to the distal oxygen. Hydrogen bonds are depicted as dashed lines. (B) Possible oxygen activation mechanism for the T252N mutant. Electron and proton transfer to the ferrous dioxygen complex gives the Fe(III)-OOH hydroperoxy intermediate. A second protonation of the distal oxygen atom lead to cleavage of the O-O bond with release of H2O and formation of the Fe(IV)=O hydroxylating species. The putative hydrogen bond network for the T252A hydroperoxy intermediate is described in a box. The hydrogen bond stabilizing the hydroperoxy intermediate by Asn252, which serves as a hydrogen bond acceptor, is depicted as a red dotted line.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yongying Jiang for a gift of proteins and assistance with GC-MS. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1 GM25515.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Abbreviations used: CYP (P450), cytochrome P450; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; ORF, open reading frames; Pd, putidaredoxin; PdR, putidaredoxin reductase; TB, Terrific Broth; GC-MS, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Kd indicates a dissociation constant estimated by measurement of the UV-visible changes in the P450 heme spectrum.

References

- 1.Ortiz de Montellano PR. In: Cytochrome P450: Structure, Mechanism, and Biochemistry. Ortiz de Montellano PR, editor. New York: Plenum Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schlichting I, Berendzen J, Chu K, Stock AM, Maves SA, Benson DE, Sweet RM, Ringe D, Petsko GA, Sligar SG. Science. 2000;287:1615–1622. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5458.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Makris TM, Denisov I, Schlichting I, Sligar SG. In: Cytochrome P450: Structure, Mechanism, and Biochemistry. Ortiz de Montellano PR, editor. New York: Plenum Press; 2005. pp. 149–182. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raag R, Poulos TL. Biochemistry. 1989;28:7586–7592. doi: 10.1021/bi00445a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raag R, Martinis SA, Sligar SG, Poulos TL. Biochemistry. 1991;30:11420–11429. doi: 10.1021/bi00112a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imai M, Shimada H, Watanabe Y, Matsushima-Hibiya Y, Makino R, Koga H, Horiuchi T, Ishimura Y. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1989;86:7823–7827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.7823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimata Y, Shimada H, Hirose T, Ishimura Y. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995;208:96–102. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cupp-Vickery JR, Poulos TL. Nature Struct. Biol. 1995;2:144–153. doi: 10.1038/nsb0295-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiang H, Tschirret-Guth RA, Ortiz de Montellano PR. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:35999–36006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005811200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hawkes DB, Adams GW, Burlingame AL, Ortiz de Montellano PR, De Voss JJ. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:27725–27732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203382200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meharenna YT, Li H, Hawkes DB, Pearson AG, De Voss J, Poulos TL. Biochemistry. 2004;43:9487–9494. doi: 10.1021/bi049293p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim D, Yukl ET, Moenne-Loccoz P, Ortiz de Montellano PR. Biochemistry. 2006;45:14772–14780. doi: 10.1021/bi061429r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verras A, Alian A, Ortiz de Montellano PR. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2006;19:491–496. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzl035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim D, Cryle MJ, De Voss JJ, Ortiz de Montellano PR. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007;464:213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Auclair K, Moenne-Loccoz P, Ortiz de Montellano PR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:4877–4885. doi: 10.1021/ja0040262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Purdy MM, Koo LS, Ortiz de Montellano PR, Klinman JP. Biochemistry. 2004;43:271–281. doi: 10.1021/bi0356045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang Y, He X, Ortiz de Montellano PR. Biochemistry. 2006;45:533–542. doi: 10.1021/bi051840z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim D, Guengerich FP. Biochemistry. 2004;43:981–988. doi: 10.1021/bi035593f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hildebrandt AG, Roots I, Tjoe M, Heinemeyer G. Methods Enzymol. 1978;52:342–350. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(78)52037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim D, Wu ZL, Guengerich FP. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:40319–40327. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508171200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagano S, Poulos TL. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:31659–31663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505261200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gorsky LD, Koop DR, Coon MJ. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:6812–6817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]