Abstract

Many recombinant eukaryotic proteins tend to form insoluble aggregates called inclusion bodies, especially when expressed in Escherichia coli. We report the first application of the technique of three-phase partitioning (TPP) to obtain correctly refolded active proteins from solubilized inclusion bodies. TPP was used for refolding 12 different proteins overexpressed in E. coli. In each case, the protein refolded by TPP gave either higher refolding yield than the earlier reported method or succeeded where earlier efforts have failed. TPP-refolded proteins were characterized and compared to conventionally purified proteins in terms of their spectral characteristics and/or biological activity. The methodology is scaleable and parallelizable and does not require subsequent concentration steps. This approach may serve as a useful complement to existing refolding strategies of diverse proteins from inclusion bodies.

Keywords: three-phase partitioning, protein refolding, recombinant ribonuclease A, CcdB mutants, human CD4, inclusion bodies

Upon expression in Escherichia coli, many recombinant proteins form dense, insoluble aggregates called inclusion bodies (Taylor et al. 1986). It is therefore necessary to develop efficient and scalable procedures for solubilization and refolding of recombinant proteins from inclusion bodies (Misawa and Kumagai 1999; Middelberg 2002). Refolding is typically carried out using either simple dilution into appropriate refolding conditions, dialysis or on a column (Stempfer et al. 1996; Rogl et al. 1998). Finding appropriate refolding conditions is generally the most difficult step of the purification process. Aggregation and precipitation of protein during refolding are commonly encountered problems. Factorial and other screens for refolding have been developed (Hofmann et al. 1995; Armstrong et al. 1999; Bajaj et al. 2004) to facilitate the search of appropriate refolding conditions. In the present study we describe the first application of the technique of three-phase partitioning (TPP) (Lovrien et al. 1995; Dennison and Lovrien 1997; Jain et al. 2004; Przybycien et al. 2004) to obtain active refolded proteins from solubilized inclusion bodies without any chromatographic steps. We have used TPP to refold 12 different proteins from inclusion bodies, namely, ribonuclease A (RNase A) (Crook et al. 1960; Wagner et al. 1983; Laity et al. 1993; delCardayré et al. 1995; Okorokov et al. 1995), the first two domains of human CD4 (CD4D12) (Dalgleish et al. 1984; Doyle and Strominger 1987; Sharma et al. 2005), five insoluble constructs of the protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) from Drosophila melanogaster (Madan and Gopal 2008), and five highly unstable and aggregation prone mutants of the E. coli proteins controller of cell division or death B (CcdB), maltose binding protein (MBP), and thioredoxin (Trx) (Chakshusmathi et al. 2004; Bajaj et al. 2005; Das et al. 2007). In each case we show that TPP-refolded protein is folded/active and that recovery yields and purification time are superior or comparable to conventional methods.

Results

The general strategy

Figure 1 schematically represents the optimized general method of refolding proteins by TPP that was applied for all the proteins studied here. The earlier experience of using TPP for concentration and purification of proteins has shown that the two critical parameters which need to be optimized are (1) ammonium sulfate concentration at each step and (2) ratio of t-butanol volume to aqueous phase volume. For application of this technique to refolding, these parameters were standardized in the case of RNase A. This standardization was carried out first with the help of native RNase A (Sigma Chemical Co.) and then extended to the inclusion bodies of recombinant RNase A. The ammonium sulfate concentration was varied from 5% (wv−1) to 50% (wv−1). Similar conditions were found to work well with inclusion bodies of other proteins. As Figure 1 shows, TPP was carried out twice. In the first step, using only 5% (wv−1) ammonium sulfate was favorable. The ratio of t-butanol to aqueous phase volume was fixed at 1:1 as this ratio has worked well in the earlier TPP experiments (Dennison and Lovrien 1997; Jain et al. 2004). The first TPP, in the case of native RNase A, did not precipitate the protein at the interfacial layer. With solubilized inclusion bodies, this step was useful in removing host cell proteins as the interfacial precipitate. TPP was repeated with the aqueous phase of the first TPP step. Again t-butanol in equal volume was added. While working with native RNase A, the amount of ammonium sulfate required to be added to recover the maximum amount of the enzyme activity as the interfacial layer was determined. This was found to be 35% (wv−1). A similar amount was then used in this step while working with solubilized inclusion bodies.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation for refolding of proteins from inclusion bodies by TPP.

At the end of the dialysis step (Fig. 1), the protein obtained with solubilized inclusion bodies of RNase A was found to be inactive. However, it was found that, while left open to air, it slowly regained activity. Maximum activity was reached at the end of 24 h. In the case of the other 11 inclusion bodies, this step was not required and active protein was obtained at the end of dialysis itself. It is worth noting that RNase A has four disulfide bridges; CD4D12 has 2; Trx has 1; CcdB, PTPs, and MBP have no disulfide bonds. In all 12 of the proteins we examined, an identical TPP procedure was followed and neither the ammonium sulfate nor the t-butanol concentration was changed. It is therefore recommended that, for a new protein, a similar procedure is followed. In case it does not work then optimization of the above two parameters can be attempted. Since the procedure is simple to implement, a variety of conditions can be screened in parallel, over the course of a few days.

Characterization of TPP-refolded RNase A

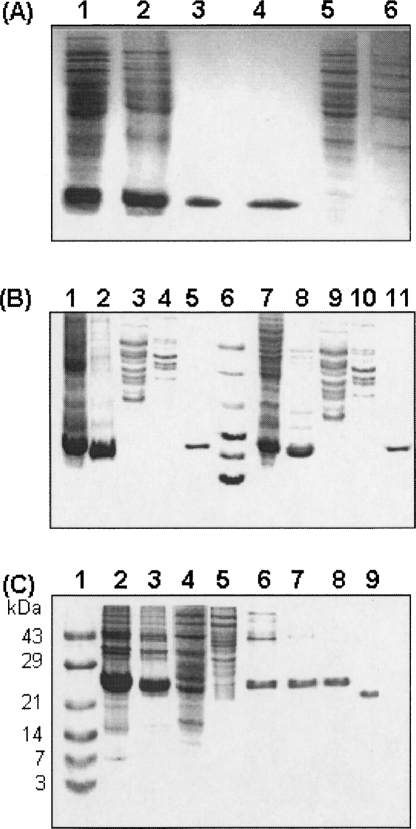

The RNase A refolded by the TPP method was characterized and compared to protein purified from inclusion bodies by the conventional method (Laity et al. 1993) as well as that obtained from a commercial source. RNase A purified from inclusion bodies without TPP required a redox buffer to ensure proper refolding. This material has identical structure and activity to nonrecombinant material purified from bovine pancreas as described previously (Laity et al. 1993). RNase A inclusion bodies at different steps of TPP were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2A). The second interfacial precipitate (lane 4) shows a single band of RNase A having a purity comparable to that of commercially available RNase A (type XIIA) from Sigma Chemical Co. (lane 3). The nondenaturing cathodic gel electrophoresis of refolded RNase A (Supplemental Fig. 1, lanes 2, 3) shows bands comparable to that of Sigma RNase A (lane 1). The fluorescence emission spectrum of the TPP-refolded RNase A upon excitation at 278 nm was compared to that of Sigma RNase A (Fig. 3A). Both have an emission maximum at 307 nm, indicating that the refolded protein is comparable to the commercially available one. The far- and near-UV CD spectra of the TPP-refolded RNase A are also comparable to that of RNase A from Sigma (Fig. 3B,C). The thermodynamic parameters for the binding of 3′-CMP to refolded RNase A obtained from isothermal titration calorimetry were compared to those obtained for the commercially available protein. The binding isotherms (Fig. 4) obtained by fitting the data to a single site binding model indicate similar thermodynamic parameters for the two RNase A samples. The values for the association constant (K a), ΔH0, ΔS, and ΔG0 for commercial (Sigma Chemical Co.) RNase A were 1.0 × 104 M−1, −12.4 kcal/mol−1, −23.1 cal/mol−1deg−1, and −6.0 kcal/mol−1, respectively, while the corresponding binding parameters obtained for the TPP-refolded RNase A were 7.4 × 103 M−1, −15.6 kcal/mol−1, −34.4 cal/mol−1deg−1, and −6.0 kcal/mol−1, respectively. Average experimental errors are ±0.5 and ±0.1 kcal/mol for ΔH0 and ΔG0, respectively. The 2′–3′ cyclic CMP hydrolyzing activity of the refolded RNase A was also compared to that of Sigma RNase A (Supplemental Fig. 2). Both samples exhibit comparable activities.

Figure 2.

TPP purification monitored by SDS-PAGE. (A) Fifteen percent SDS-PAGE analysis of RNase A inclusion bodies at different steps of TPP; (lane 1) unwashed inclusion bodies; (lane 2) washed inclusion bodies with 50 mM PBS/pH 7.4/1 mM EDTA containing 2 M urea; (lane 3) commercial RNase A (Sigma Chemical Co.); (lane 4) refolded RNase A obtained from interfacial precipitate of second TPP; (lane 5) interfacial precipitate of first TPP; (lane 6) aqueous phase of second TPP. (B) Fifteen percent SDS-PAGE analysis of inclusion bodies of CcdB mutants subjected to TPP; (lane 1) unwashed inclusion bodies of CcdB-F17P; (lane 2) washed inclusion bodies of CcdB-F17P with 50 mM PBS/pH 7.4/0.5% Triton X-100; (lane 3) interfacial precipitate of first TPP; (lane 4) aqueous phase of second TPP; (lane 5) refolded and purified CcdB-F17P by TPP; (lane 6) molecular weight marker; (lane 7) unwashed inclusion bodies of CcdB-M97K; (lane 8) washed inclusion bodies of CcdB-M97K; (lane 9) interfacial precipitate of first TPP; (lane 10) aqueous phase of second TPP; (lane 11) refolded and purified CcdB-M97K by TPP. (C) Fifteen percent SDS-PAGE analysis of inclusion bodies of CD4D12 subjected to TPP CD4D12; (lane 1) molecular weight marker; (lane 2) unwashed inclusion bodies of CD4D12; (lane 3) washed inclusion bodies of CD4D12 with 50 mM PBS/pH 7.4/0.5% Triton X-100; (lane 4) interfacial precipitate of first TPP; (lane 5) aqueous phase of second TPP; (lane 6) refolded and purified CD4D12 by TPP; (lane 7) refolded and purified CD4D12 after subjected to the 50-kDa polyethersulfone membrane (PALL Lifesciences) once; (lane 8) refolded and purified CD4D12 after subjected to the 50-kDa polyethersulfone membrane (PALL Lifesciences) twice; (lane 9) refolded and purified CD4D12 in the absence of DTT.

Figure 3.

Spectroscopic characterization of refolded RNase A. (A) Fluorescence emission spectra of RNase A. The samples at a concentration of 100 μg/mL−1 (∼7 μM) were excited at 278 nm and the emission spectra from 290 to 400 nm were recorded, using excitation and emission slit widths of 2 nm and 5 nm, respectively. Fluorescence spectra of unfolded RNase A (3), refolded RNase A (2), Sigma RNase A (1) are shown after correction for buffer contribution. (B) The far-UV CD spectra of refolded RNase A (○) and Sigma RNase A (△) for 0.5 mg/mL−1 protein recorded in a 1-mm path length cuvette from 200 to 250 nm. (C) The near-UV CD spectra of the two samples recorded for 0.5 mg/mL−1 protein in a 1-cm path length cuvette from 250 to 350 nm. The symbols are the same as in B.

Figure 4.

The binding isotherm of RNase A and 3′-CMP. RNase A (55 μM) in 0.2 M sodium acetate buffer, pH 6.0 containing 0.2 M NaCl, was titrated with small injections of 3′-CMP solution in the same buffer. The enthalpy data were fitted to a single site binding model. (A) Binding isotherm for refolded RNase A; (B) binding isotherm for Sigma RNase A.

Characterization of TPP-refolded CcdB

The SDS-PAGE of the CcdB mutants at different steps of TPP is shown in Figure 2B. Characterization of the two TPP-purified single-site mutants, CcdB-F17P and CcdB-M97K, was carried out using fluorescence and circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy and compared to wild-type (WT) CcdB purified by conventional methods. Comparison of the fluorescence and CD spectra of the TPP-refolded CcdB mutants with those of WT-CcdB indicated a well-folded structure. CcdB is predominantly a β-sheet protein. The CD spectrum of the WT shows a minimum at 208 nm, characteristic of β-sheet content (Fig. 5). The CD spectra of the two single-site mutants, CcdB-F17P and M97K, also showed the characteristic minima at 208 nm (Fig. 5, i); however, there were slight alterations in the spectra especially for the M97K mutant. The fluorescence spectrum showed a maximum at 340 nm in native buffer. When the protein is unfolded in guanidium chloride (GdmCl), the maximum is shifted to 360 nm (Fig. 5, ii). The fluorescence spectrum of the F17P mutant showed a maximum at 340 nm for the folded protein, similar to WT as well as the expected shift to higher wavelength upon denaturation (Fig. 5, ii). In contrast to the WT, the fluorescence decreased upon denaturation. In the case of the M97K mutant, the fluorescence maximum of the native protein was redshifted to 350 nm. This might be because the M97K mutation perturbs the fluorescence of the nearby W99 residue. Like WT-CcdB, this mutant also shows an increase in fluorescence intensity upon denaturation.

Figure 5.

(i) Far-UV CD spectra for CcdB proteins in 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5: WT-CcdB (●), CcdB-F17P (○), and CcdB-M97K (△). (ii) Fluorescence emission spectra (AU, arbitrary units) from 300 to 400 nm for CcdB proteins in 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, using excitation and emission slit widths of 2 nm and 5 nm, respectively. Protein samples at a concentration of ∼1 μM were incubated either in buffer (●) or in buffer containing 5 M GdmCl (○) for 3 h before spectral acquisition. (A) WT-CcdB, (B) CcdB-F17P, and (C) CcdB-M97K.

Equilibrium unfolding studies in the presence of GdmCl were also carried out for all three proteins at 25°C. The denaturation data were fitted to a two-state unfolding model with subunit dissociation (Bajaj et al. 2004) to obtain values of ΔG° and C m (Fig. 6). WT-CcdB was calculated to have a free energy of unfolding (ΔG°) of 21.3 (±0.4) kcal/mol−1 and a C m of 2.2 (±0.07) M. These values are similar to the values obtained for WT-CcdB from earlier studies (Bajaj et al. 2004). The ΔG° and C m values obtained for CcdB-F17P were 12.2 (±0.3) kcal/mol−1 and 0.6 (±0.2) M, respectively. This indicates that the F17P mutation is a highly destabilizing mutation. The unfolding transition for the CcdB-M97K mutant did not show a sigmoidal transition and hence could not be fitted to the two-state unfolding model (Fig. 6, bottom panel). In contrast to the refolded material that was obtained by TPP, the CcdB mutants could not be purified by conventional refolding of the inclusion bodies as described in Materials and Methods. When cells were grown in the presence of the compatible solutes sorbitol or betaine, a small fraction of the protein was found in the soluble fraction. However, this degraded during protein purification, even when purification was carried out in the presence of sorbitol/betaine and protease inhibitors.

Figure 6.

Equilibrium GdmCl denaturation profiles for CcdB proteins in 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, at 25°C. (Top panel) WT-CcdB, (middle panel) CcdB-F17P, and (bottom panel) CcdB-M97K. The theoretical curves (black line) were obtained for WT-CcdB and CcdB-F17P by fitting the melts to a global fit function of two-state unfolding in conjunction with subunit dissociation for a dimeric protein. The data for the M97K mutant could not be fitted, though there may be an unfolding transition between 0 and 0.5 M.

Characterization of MBP and Trx mutants refolded by TPP

Two mutants of MBP with substitutions of buried hydrophobic residues by Asp had been made previously in order to examine if phenotypes/solubilities of Asp mutants could be used to probe residue burial in proteins (Bajaj et al. 2005). Similar to the situation with CcdB, these could not be refolded/purified by conventional chromatographic procedures but were successfully refolded by TPP. Following TPP, the mutants were shown to be active in a maltose binding assay monitored by fluorescence spectroscopy (Supplemental Table 1; Ganesh et al. 1997). The SDS-PAGE profiles for the MBP mutants obtained after the second round of TPP are shown in Supplemental Figure 3A. In other work aimed at studying the effect of signal peptide on protein stability, the signal peptide of MBP had been fused to Trx. The resulting protein was insoluble and refractory to conventional refolding procedures. However, using TPP the protein was purified in high yield and was shown to be active by its ability to catalyze insulin reduction (Supplemental Table 2). The SDS-PAGE profile for the Trx mutant obtained after second round of TPP is shown in Supplemental Figure 3B.

Characterization of CD4D12 refolded by TPP

The SDS-PAGE of CD4D12 refolded by TPP is shown in Figure 2C. The characterization of refolded CD4D12 protein was carried out by CD and fluorescence spectroscopy and its activity was determined using surface plasmon resonance (SPR). The CD and fluorescence spectra of refolded CD4D12 (Fig. 7) are similar to that obtained earlier for this protein (Sharma et al. 2005) indicating that the protein is correctly folded. The CD spectrum showed a minimum at 210 nm characteristic of β-sheet proteins. The fluorescence spectrum showed an emission maximum at 344 nm. CD4D12 activity was assayed for its ability to bind HIV-1 gp120 using SPR as described previously (Varadarajan et al. 2005). Figure 7C shows that TPP-refolded CD4D12 binds gp120 immobilized on the chip surface as has been shown previously for CD4D12 prepared by conventional methods. The K d value for the binding was estimated to be 11 nM, similar to the previously published values of 15–20 nM for the gp120:CD4D12 complex (Sharma et al. 2005). We had previously shown that CD4D12 purified without TPP was highly aggregation prone (Sharma et al. 2005). The protein aggregated upon storage at 4°C within a few days and even upon thawing of frozen solutions. In contrast, material purified by TPP did not aggregate under either of these conditions. The protein concentration after dialysis for this protein was 0.5 mg/mL.

Figure 7.

(A) Fluorescence emission spectrum of CD4D12 in PBS, pH 7.4, from 300 to 420 nm using excitation and emission slit widths of 2 nm and 5 nm, respectively. Fluorescence spectra of unfolded CD4D12 (2), refolded CD4D12 (1). (B) Far-UV CD spectrum of CD4D12 in PBS, pH 7.4. (C) Biacore data: sensorgram overlays for the binding of different concentrations of CD4D12 to surface immobilized gp120. Traces 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively, indicate 50 nM, 100 nM, 150 nM, and 200 nM concentrations of CD4D12. Surface density 1000RU; buffer 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4)-150 mM NaCl-3 mM EDTA–0.005% P20; flow rate, 30 μL/min−1. The dissociation constant K d for the gp120:CD4D12 complex was estimated to be 11 nM from the Biacore data.

Table 1 summarizes the comparison of the results obtained by TPP with other reported methods in the case of these proteins. The data on the characterization of the proteins refolded by TPP are given in Table 2.

Table 1.

Comparison of results obtained by TPP with conventional methods

Table 2.

Characterization of different proteins refolded by TPP

Characterization of PTP domains of D. melanogaster refolded by TPP

The SDS-PAGE profiles for the PTP constructs obtained after the second round of TPP are shown in Figure 8. The PTPs once purified were tested for phosphatase activity using para-nitro phenyl phosphate (pNPP) as the substrate as reported earlier (Madan and Gopal 2008). Phosphatase activity of the TPP-purified proteins was compared with the catalytic activity of PTPs purified from the soluble fraction using Ni-NTA affinity chromatography. These latter constructs purified by conventional methods had an additional 45 residues at the N terminus. This extension was essential for preventing these PTP domains from forming inclusion bodies upon overexpression in E. coli (Madan and Gopal 2008). Most constructs lacking the N-terminal extension could not be refolded by conventional methods and could only be refolded using TPP. All the constructs used for TPP lacked this N-terminal extension. As can be seen from Figure 8, four of five PTPs purified by TPP (DPTP52F, DLAR, DPTP99A, and DPTP69) showed comparable or more phosphatase activity as compared to the proteins purified by conventional methods. DPTP10D was found to be inactive although 18 mg/L−1 of the protein was obtained by TPP purification, which was ninefold higher compared to the yield obtained when the protein was refolded by rapid dilution (Table 1). The data show that, with the possible exception of the DPTP10D construct, the N-terminal extension is not required for activity of the protein.

Figure 8.

(A) Twelve percent SDS-PAGE showing isolated and washed inclusion bodies of Drosophila PTPs after sonication. Lane 1 shows the molecular weight marker. Lanes 2–6 show the isolated inclusion bodies of DPTP52F, DPTP69D, DPTP99A, DLAR, and DPTP10D, respectively. (B) Twelve percent SDS-PAGE showing the purified Drosophila PTPs after second round of TPP. Lanes 1–5 show the interfacial precipitates of DPTP52F, DPTP69D, DPTP99A, DLAR, and DPTP10D, respectively. (C) Phosphatase activity of Drosophila PTPs purified by TPP of 8 M urea solubilized inclusion bodies (dark gray). The PTP activity was measured in the interfacial precipitates obtained after the second round of TPP. Phosphatase activity obtained is much more than that of PTP constructs harboring an N-terminal extension of 45 amino acids and purified by conventional methods (light gray). No activity was recovered for DPTP10D (*). One unit liberates one micromole of para-nitrophenol/min at 37°C, pH 7.2, under these assay conditions.

Discussion

While TPP has previously been used for protein concentration and purification (Dennison and Lovrien 1997; Jain et al. 2004), in the present study we have applied TPP to successfully refold and purify a variety of recombinant proteins from inclusion bodies, several of which could not be purified by conventional procedures. There is a debate about the exact mechanism of TPP-mediated refolding (Lovrien et al. 1995; Dennison and Lovrien 1997; Jain et al. 2004; Kiss and Borbas 2003). However, both ammonium sulfate and alcohols have been reported to be useful additives during refolding (Middelberg 2002). While ammonium sulfate is more widely known as a useful additive during refolding, t-butanol has also been reported to promote refolding of heat denatured glutamate dehydrogenase (Lovrien et al. 1995). It is also possible that, in most of the (other) cases, t-butanol also acts as an “aggregation suppressor” (Tsumoto et al. 2003), since a mildly hydrophobic alkyl group in this case would bind to exposed hydrophobic groups in unfolded protein molecules/folding intermediates. The protein refolding during TPP, thus, appears to be caused by the synergy of ammonium sulfate and t-butanol in acting as a “folding enhancer” (Tsumoto et al. 2003). These molecules stabilize the native structure of proteins and typically facilitate unfolded proteins/folding intermediates to collapse into compact structures, though in some cases such additives can promote aggregation (Tsumoto et al. 2003; Lange et al. 2005).

We show that TPP-mediated refolding from inclusion bodies works for proteins with and without disulfide bonds, for single- and multidomain proteins and for monomeric and dimeric ones. The methodology is scaleable and parallelizable and, unlike refolding by dilution, does not require subsequent concentration steps. In fact, here the refolded protein is obtained as a precipitate which can be dissolved/formulated in a desired fashion. We anticipate that this simple methodology will serve as a useful complement to existing methods for refolding of diverse proteins from inclusion bodies.

Materials and Methods

Strains and expression plasmids

E. coli BL21 (DE3) was used for protein expression of RNase A, mutants of MBP and Trx, human CD4D12, PTPs. E. coli CSH501 was used for expressing WT-CcdB and its mutants. The plasmids used for expression of these proteins were pET-22b(+) containing RNase A insert (kindly provided by Drs. H. Scheraga and M. Narayan, Cornell University), pBAD24 containing MBP224D and MBP264D inserts, pET20b(+) containing (A14E)malETrx insert, pET-28a containing human CD4D12 insert (kindly provided by Dr. M.M. Balamurali, Indian Institute of Science), pET22b containing DLAR, DPTP10D, DPTP69D, DPTP52F, and DPTP99A inserts, and pBAD24 containing CcdB-F17P and CcdB-M97K inserts.

Overexpression in E. coli

The plasmid pET-22b(+) containing the coding region for full-length bovine pancreatic RNase A insert was transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3). A single colony was picked and inoculated into 5 mL LB medium containing 100 μg/mL−1 ampicillin. The tube was shaken overnight at 37°C at 200 rpm. One percent of primary inoculum was transferred into 1 L fresh LB broth (amp+) and grown at 37°C with vigorous shaking until A600 reached 0.8. Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mM and the culture was further grown under similar conditions for 12 h. The above procedure was repeated for the transformation of the plasmids pBAD24 containing MBP224D and MBP264D inserts, pET22b containing DLAR, DPTP10D, DPTP69D, DPTP52F, and DPTP99A inserts, and pET20b(+) containing (A14E)malETrx insert (showing leaky expression) into E. coli BL21 (DE3). The plasmid pET-28a expressing CD4D12 was transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3), and 50 μg/mL−1 kanamycin was used as the selection marker. In case of MBP224D and MBP264D, induction was carried out by adding L-arabinose (0.2%) and the culture was further grown under similar conditions for 12 h. The plasmid pBAD24 expressing CcdB mutants F17P or M97K was transformed into expression strain E. coli CSH501. Induction was carried out by adding L-arabinose (0.2%) and the culture was further grown under similar conditions for 12 h.

Isolation of inclusion bodies

Cells were harvested, sonicated in resuspension buffer (RNase A, and CcdB mutants, 50 mM Tris/pH 8.0/1 mM EDTA/10% glycerol/200 μM PMSF; MBP mutants, Trx mutant, and PTPs, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, containing 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 100 μM PMSF; CD4D12, PBS/pH 7.4/100 μM PMSF) 10 times with 30-sec pulses on ice, and centrifuged at 9000g for 30 min at 4°C. The inclusion body pellet was washed (thrice) with washing buffer (RNase A, 50 mM PBS/pH 7.4/1 mM EDTA and further with buffer containing 2 M urea; CcdB mutants, MBP mutants, Trx mutant, PTPs, and CD4D12, 50 mM PBS/pH 7.4/0.5% Triton X-100) and centrifuged at 9000g for 30 min.

Refolding and purification of proteins without TPP

Upon expression, RNase A was found in inclusion bodies. Inclusion bodies were suspended in 7 M GdmCl in 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, containing 3 mM EDTA at room temperature for 3 h. The suspension was then diluted with ice-cold 20 mM acetic acid and dialyzed extensively against 20 mM acetic acid at 4°C. This was then centrifuged at 12,000g at 4°C, and to the supernatant were added GSH, GSSG, and arginine to final concentrations of 2.5 mM, 1.25 mM, and 0.5 M, respectively. The pH of this mixture was adjusted to pH 8.0 and dialyzed extensively against 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 at 4°C to refold the protein. Dialysis was carried out for 48 h with buffer changes every 6 h. The enzyme was finally purified by cation exchange chromatography using a Mono S HR5/5 column (Laity et al. 1993).

WT-CcdB was expressed in soluble form. After cell lysis, protein was purified from the soluble fraction by ammonium sulfate fractionation followed by gel filtration and anion exchange chromatography as described earlier (Bajaj et al. 2004). Many destabilized mutants of CcdB including F17P and M97K are targeted to inclusion bodies. In order to purify the F17P and M97K mutants, two different approaches were taken. In the first approach, inclusion bodies were treated as described in Citovsky et al. (1990). The pellet obtained after sonication of the cells was resuspended in buffer L (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, and 1 mM PMSF) with 1 M NaCl followed by centrifugation at 12,000g for 5 min at 4°C. The pellet obtained was treated with 4 M urea at 70°C followed by resuspension again in 4 M urea at 56°C. Finally the solubilized protein was separated from insoluble aggregates by centrifugation at 15,000g for 10 min at 4°C. This was then extensively dialyzed against buffer L to refold the protein, which was then purified by gel filtration chromatography. Since yields were very low using the above procedure, expression and purification of F17P and M97K were attempted in the presence of compatible solutes such as 0.5 M sorbitol and 10 mM betaine (Barth et al. 2000). Cells were grown to an A600 of 0.5 at 37°C, supplemented with 0.5 M sorbitol, 4% NaCl, and 10 mM betaine and incubated for an additional 30 min before induction with 0.2% arabinose. After overnight incubation, cells were harvested and resuspended in lysis buffer (75 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF). Cells were sonicated and the nucleic acids were precipitated by 0.01% polyethylene glycol at 4°C. The solution was made 80% (wv−1) in ammonium sulfate at 4°C. The pellet was redissolved in 3–6 mL of 20 mM Tris, pH 8.5, and loaded on a Sephacryl S-100 gel filtration column pre-equilibrated with the same buffer at 4°C. The fractions containing CcdB were pooled and purified using a Resource Q (6 mL, Amersham-Pharmacia) ion exchange column at room temperature using a gradient of 50 mM to 300 mM NaCl. For both of these mutants, the proteins were observed to be degraded during gel filtration and no protein was observed after ion exchange chromatography. Attempts were made to purify in the presence of sorbitol and betaine by incorporating these solutes in the resuspension, gel filtration, and ion-exchange equilibration buffers, but even then neither mutant could be purified. Similar attempts to refold and purify mutants of MBP, Trx, and all PTP constructs lacking an N-terminal extension were unsuccessful.

His-tagged CD4D12 was purified from inclusion bodies essentially as described previously (Varadarajan et al. 2005). The inclusion bodies were resuspended in 6 M GdmCl in PBS at room temperature for 4 h. The solution was then centrifuged at 9000g for 30 min to remove insoluble material. The supernatant was applied to a Ni-NTA column and eluted under denaturing conditions with 6 M GdmCl in PBS containing 300 mM imidazole at room temperature. The eluted sample was extensively dialyzed against PBS at 4°C to get the refolded protein.

Refolding of solubilized inclusion bodies by three-phase partitioning (TPP)

Washed inclusion bodies were subjected to solubilization with 8 M urea/100 mM DTT at 25°C for 3 h. The solubilized sample was saturated with ammonium sulfate (5%, wv−1) and vortexed gently to dissolve the salt. Following this, t-butanol was added in 1:1 (vv−1) ratio of solubilized sample to t-butanol. After incubation for 1 h at 25°C, the mixture was centrifuged (4000g for 5 min) to facilitate separation of phases. Three phases were formed: the upper organic phase, an interfacial precipitate, and lower aqueous phase (see Fig. 1). The aqueous layer was subjected to a second round of TPP. The aqueous phase was saturated with ammonium sulfate (35%, wv−1) followed by addition of t-butanol (in 1:1 [vv−1] ratio of aqueous phase to t-butanol). Again three phases were formed and collected. The interfacial precipitate was dissolved and dialyzed against 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.1, containing 0.1 M NaCl in case of RNase A; 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 for CcdB mutants; 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, containing 150 mM NaCl in case of MBP mutants; 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.0 in case of Trx mutant; 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, containing 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA in case of PTPs; PBS, pH 7.0, for CD4D12 (two changes at an interval of 2 h and final dialysis for 6–7 h at 4°C). In all the cases the interfacial precipitate from the second TPP was used after dissolution and dialysis for activity measurements. In case of CD4D12 to remove a few higher molecular weight contaminants, the refolded protein solution was subjected to ultrafiltration using a 50-kDa polyethersulfone membrane (PALL Lifesciences). In the control experiment, solubilized inclusion body samples of the same protein concentration were subjected to dialysis for the same time without TPP. For refolding RNase A, after dialysis the sample was kept for air oxidation in an open vessel at 25°C for 24 h.

Assay for RNase A

The activity of refolded RNase A was assayed using the method of Crook et al. (1960) to monitor hydrolysis of 2′–3′ cyclic CMP (Sigma Chemical Co.) to cytidine 3′ monophosphate.

Assay for PTPs

The phosphatase activity was assayed using pNPP as the substrate (Madan and Gopal 2008).

Binding assay for MBP

The binding of maltose to MBP was assayed fluorimetrically by observing a redshift and quenching in the intrinsic tryptophan of MBP upon maltose binding (Ganesh et al. 1997).

Assay for Trx

The activity of Trx was assayed by the insulin aggregation assay (Das et al. 2007).

Protein estimation

The protein concentrations were estimated using an extinction coefficient of 9.56 mM−1cm−1 for RNase A (Connelly et al. 1990), 1.4 mL/mg−1cm−1 for CcdB (Van Melderen et al. 1996), and 18,450 M−1cm−1 for CD4D12 as calculated from the amino acid sequence (Pace et al. 1995). The protein concentration of pure MBP was estimated using 1.46 mL/mg−1cm−1 as an extinction coefficient (Ganesh et al. 1997). The protein concentration in other cases was estimated by the dye-binding method using bovine serum albumin as the standard protein (Bradford 1976).

Gel electrophoresis

SDS-PAGE was performed according to Laemmli (1970). Proteins were visualized using Coomassie Blue stain. Cathodic gel electrophoresis under nondenaturing condition in the case of RNase A was performed as described in Goldenberg (1989), using β-alanine/acetic acid, pH 4.0. Ten percent polyacrylamide gel was run at 20 mA at 4°C. Fixing and staining were performed with 12.5% trichloroacetic acid and 0.1% Coomassie Brilliant Blue.

Fluorescence measurements

Fluorescence spectra of the refolded proteins were recorded on a SPEX Fluoromax 3 spectrofluorimeter at 25°C using a 1-cm cuvette. For RNase A, 100 μg/mL−1 (∼7 μM) protein was taken in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and the fluorescence emission spectrum was recorded from 290 to 400 nm upon excitation at 278 nm. The excitation and emission slit widths were kept at 2 nm and 5 nm, respectively. For the other proteins, excitation was at 280 nm, and emission in the 300–400 nm range was recorded in each case with excitation and emission slit widths of 2 nm as described previously (Bajaj et al. 2004). Typically, 0.5–1.0 μM protein in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, was used for the CcdB and CD4D12 proteins. All fluorescence spectra were normalized and corrected for buffer contributions.

Circular dichroism measurements

Far-UV CD spectra were recorded on a Jasco J715 spectropolarimeter using a cell with a path length of 0.1 cm. Typical spectral accumulation parameters were a scanning rate of 50 nm/min with a 2-nm bandwidth over the wavelength range 195–250 nm for the CcdB mutants and CD4D12 and 200–250 nm for RNase A with six scans averaged for each far-UV spectrum. The protein concentrations were 0.5 mg/mL−1 in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, for RNase A and 10–15 μM for the CcdB and CD4D12 proteins in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5. The CD data are presented in terms of mean residue ellipticity (MRE) as a function of wavelength, calculated according to the procedure described earlier (Schmid 1989) using a protein concentration of 20 μM. All CD spectra were corrected for buffer contributions. The near-UV CD of RNase A was recorded from 250 to 340 nm using 0.5 mg/mL−1 (∼35 μM) protein in a 1-cm path length cuvette.

Isothermal titration calorimetry of 3′-CMP binding to RNase A

The thermodynamic parameters for the binding of 3′-CMP to RNase A were determined by ITC; 55 μM RNase A was taken in 0.2 M Na acetate buffer, pH 6.0, containing 0.2 M NaCl in the calorimeter cell and titrated with 3, 5, or 10 μL injections of 2.0 mM 3′-CMP solution in the same buffer from the syringe at 25°C. The enthalpy data thus obtained were fitted to a single site binding model to determine the thermodynamic parameters of binding.

Isothermal denaturation

Equilibrium unfolding as a function of GdmCl concentration was monitored by fluorescence spectroscopy. Fluorescence measurements were performed using a SPEX Fluoromax-3 spectrofluorimeter with a 1-cm cell at 25°C. The excitation wavelength was fixed at 280 nm and the emission wavelength was 385 nm for WT-CcdB, 340 nm for CcdB-F17P, and 350 nm for CcdB-M97K. The slit widths were 2 nm for both excitation and emission monochromators. Each measurement was an average of three readings. The concentration of GdmCl was calculated from measurements of the refractive index. The unfolding data were fitted to a function described previously (Bajaj et al. 2004) to obtain values of ΔG° and C m.

Biacore experiments

All experiments were performed with a BIACORE 2000 (Biacore) optical biosensor at 25°C. One thousand resonance units of purified JR-CSF gp120 were attached by amine coupling to the surface of a CM5 chip. Binding of various concentrations of TPP-refolded CD4D12 to the surface immobilized gp120 was examined. A naked sensor surface without gp120 served as a negative control for each binding interaction. Serial dilutions of CD4D12 were run across each sensor surface at four different concentrations in a running buffer of PBS + 0.05% Tween-20 at a flow rate of 30 μL/min. In all cases, the sensor surface was regenerated between each binding reaction by using one to two washes of 10 mM NaOH for 60 sec at 10 μL/min. Each binding curve was corrected for nonspecific binding by subtraction of the signal obtained from the negative control flow cell. Kinetic constants for association and dissociation were derived from linear transformations of the exported binding data using at least four concentrations of analyte. Kinetic parameters obtained were compared with those estimated by fitting the data to the simple 1:1 Langmuir interaction model by using the BIA EVALUATION 3.1 software.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge partial financial support provided by the Department of Science and Technology (DST) and Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India Organizations. Financial support provided by ICMR to S.R. in the form of a Senior Research Fellowship is also gratefully acknowledged. M.D. and B.B. are DBT postdoctoral fellows. We thank Dr. R. Kulothungan for the Trx mutant plasmid.

Footnotes

Supplemental material: see www.proteinscience.org

Reprint requests to: Munishwar N. Gupta, Chemistry Department, Indian Institute of Technology Delhi, Hauz Khas, New Delhi 110 016, India; e-mail: munishwar48@yahoo.co.uk; fax: 91-011-26581073.

Abbreviations: CcdB, controller of cell division or death B; CD4D12, first two domains of human CD4; C m, the denaturant concentration at which one half of the protein molecules are unfolded; GdmCl, guanidium chloride; IPTG, isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside; MBP, maltose binding protein; PTPs, protein tyrosine phosphatases; RNase A, ribonuclease A; SPR, surface plasmon resonance; TPP, three-phase partitioning; Trx, E. coli thioredoxin.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.036939.108.

References

- Armstrong, N., de Lencastre, A., Gouaux, E. A new protein folding screen: Application to the ligand binding domains of a glutamate and kainate receptor and to lysozyme and carbonic anhydrase. Protein Sci. 1999;8:1475–1483. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.7.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj, K., Chakshusmathi, G., Bachhawat-Sikder, K., Surolia, A., Varadarajan, R. Thermodynamic characterization of monomeric and dimeric forms of CcdB (controller of cell division or death B protein) Biochem. J. 2004;380:409–417. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj, K., Chakrabarti, P., Varadarajan, R. Mutagenesis-based definitions and probes of residue burial in proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005;102:16221–16226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505089102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth, S., Huhn, M., Matthey, B., Klimka, A., Galinski, E.A., Engert, A. Compatible-solute-supported periplasmic expression of functional recombinant proteins under stress conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:1572–1579. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.4.1572-1579.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakshusmathi, G., Mondal, K., Lakshmi, G.S., Singh, G., Roy, A., Ch, R.B., Madhusudhanan, S., Varadarajan, R. Design of temperature-sensitive mutants solely from amino acid sequence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004;101:7925–7930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402222101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citovsky, V., Knorr, D., Schuster, G., Zambryski, P. The P30 movement protein of tobacco mosaic virus is a single-strand nucleic acid binding protein. Cell. 1990;60:637–647. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90667-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, P.R., Varadarajan, R., Sturtevant, J.M., Richards, F.M. Thermodynamics of protein-peptide interactions in the ribonuclease S system studied by titration calorimetry. Biochemistry. 1990;29:6108–6114. doi: 10.1021/bi00477a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook, E.M., Mathias, A.P., Rabin, B.R. Spectrophotometric assay of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease by the use of cytidine 2′:3′-phosphate. Biochem. J. 1960;74:234–238. doi: 10.1042/bj0740234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgleish, A.G., Beverley, P.C., Clapham, P.R., Crawford, D.H., Greaves, M.F., Weiss, R.A. The CD4 (T4) antigen is an essential component of the receptor for the AIDS retrovirus. Nature. 1984;312:763–767. doi: 10.1038/312763a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das, M., Kobayashi, M., Yamada, Y., Sreeramulu, S., Ramakrishnan, C., Wakatsuki, S., Kato, R., Varadarajan, R. Design of disulfide-linked thioredoxin dimers and multimers through analysis of crystal contacts. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;372:1278–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- delCardayré, S.B., Ribo, M., Yokel, E.M., Quirk, D.J., Rutter, W.J., Raines, R.T. Engineering ribonuclease A: Production, purification and characterization of wild-type enzyme and mutants at Gln11. Protein Eng. 1995;8:261–273. doi: 10.1093/protein/8.3.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennison, C., Lovrien, R. Three phase partitioning: Concentration and purification of proteins. Protein Expr. Purif. 1997;11:149–161. doi: 10.1006/prep.1997.0779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, C., Strominger, J.L. Interaction between CD4 and class II MHC molecules mediates cell adhesion. Nature. 1987;330:256–259. doi: 10.1038/330256a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh, C., Shah, A.N., Swaminathan, C.P., Surolia, A., Varadarajan, R. Thermodynamic characterization of the reversible, two-state unfolding of maltose binding protein, a large two-domain protein. Biochemistry. 1997;36:5020–5028. doi: 10.1021/bi961967b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg, D.P. Analysis of protein conformation by gel electrophoresis. In: Creighton T.E., editor. Protein structure. A practical approach. Oxford University Press; UK: 1989. pp. 225–250. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, A., Tai, M., Wong, W., Glabe, C.G. A sparse matrix screen to establish initial conditions for protein renaturation. Anal. Biochem. 1995;230:8–15. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain, S., Singh, R., Gupta, M.N. Purification of recombinant green fluorescent protein by three-phase partitioning. J. Chromatogr. A. 2004;1035:83–86. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss, E., Borbas, R. Protein adsorption at liquid/liquid interface with low interfacial tension. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2003;31:169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laity, J.H., Shimotakahara, S., Scheraga, H.A. Expression of wild-type and mutant bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A in Escherichia coli . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1993;90:615–619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange, C., Patil, G., Rudolph, R. Ionic liquids as refolding additives: N′-alkyl and N′-(ω-hydroxyalkyl) N-methylimidazolium chlorides. Protein Sci. 2005;14:2693–2701. doi: 10.1110/ps.051596605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovrien, R.E., Conroy, M.J., Richardson, T.I. Molecular basis for protein separations. In: Gregory R.B., editor. Protein-solvent interactions. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1995. pp. 521–553. [Google Scholar]

- Madan, L.L., Gopal, B. Addition of a polypeptide stretch at the N-terminus improves the expression, stability and solubility of recombinant protein tyrosine phosphatases from Drosophila melanogaster . Protein Expr. Purif. 2008;57:234–243. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middelberg, A.P.J. Preparative protein refolding. Trends Biotechnol. 2002;20:437–443. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(02)02047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misawa, S., Kumagai, I. Refolding of therapeutic proteins produced in Escherichia coli as inclusion bodies. Biopolymers. 1999;51:297–307. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1999)51:4<297::AID-BIP5>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okorokov, A.L., Panov, K.I., te Poele, R.H., Breukelman, H.J., Furia, A., Karpeisky, M., Beintema, J.J. An efficient system for active bovine pancreatic ribonuclease expression in Escherichia coli . Protein Expr. Purif. 1995;6:472–480. doi: 10.1006/prep.1995.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace, C.N., Vajdos, F., Fee, L., Grimsley, G., Gray, T. How to measure and predict the molar absorption coefficient of a protein. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2411–2423. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przybycien, T.M., Pujar, N.S., Steele, L.M. Alternative bioseparation operations: Life beyond packed-bed chromatography. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2004;15:469–478. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogl, H., Kosemund, K., Kuhlbrandt, W., Collinson, I. Refolding of Escherichia coli produced membrane protein inclusion bodies immobilised by nickel chelating chromatography. FEBS Lett. 1998;432:21–26. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00825-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, F.X. Spectral methods of characterizing protein conformation and conformational changes. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, D., Balamurali, M.M., Chakraborty, K., Kumaran, S., Jeganathan, S., Rashid, U., Ingallinella, P., Varadarajan, R. Protein minimization of the gp120 binding region of human CD4. Biochemistry. 2005;44:16192–16202. doi: 10.1021/bi051120s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stempfer, G., Holl-Neugebauer, B., Rudolph, R. Improved refolding of an immobilized fusion protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 1996;14:329–334. doi: 10.1038/nbt0396-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanimizu, N., Ueno, H., Hayashi, R. Replacement of His12 or His119 of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A with acidic amino acid residues for the modification of activity and stability. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2002;94:39–44. doi: 10.1263/jbb.94.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, G., Hoare, M., Gray, D.R., Marston, F.A.O. Size and density of protein inclusion bodies. Biotechnology. 1986;43:553–557. [Google Scholar]

- Tsumoto, K., Ejima, D., Kumagai, I., Arakawa, T. Practical considerations in refolding proteins from inclusion bodies. Protein Expr. Purif. 2003;28:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s1046-5928(02)00641-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Melderen, L., Thi, M.H., Lecchi, P., Gottesman, S., Couturier, M., Maurizi, M.R. ATP-dependent degradation of CcdA by Lon protease. Effects of secondary structure and heterologous subunit interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:27730–27738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varadarajan, R., Sharma, D., Chakraborty, K., Patel, M., Citron, M., Sinha, P., Yadav, R., Rashid, U., Kennedy, S., Eckert, D., et al. Characterization of gp120 and its single-chain derivatives, gp120-CD4D12 and gp120-M9: Implications for targeting the CD4i epitope in human immunodeficiency virus vaccine design. J. Virol. 2005;79:1713–1723. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1713-1723.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, A.P., Iordachel, M.C., Wagner, L.P. A simple spectrophotometric method for the measurement of ribonuclease activity in biological fluids. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods. 1983;8:291–297. doi: 10.1016/0165-022x(83)90003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]