Abstract

IL-10 reduces cytokine expression in non-muscle tissues, but its effect on skeletal muscle remains undefined. Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that endogenous IL-10 acts to reduce cytokines in the gastrocnemius muscle by comparing IL-6 and TNFα expression in wild-type (IL-10+/+) and IL-10 deficient (IL-10−/−) mice following an inflammatory insult induced by peripheral LPS. IL-6 mRNA expression increased following LPS for both IL-10+/+ and IL-10−/− mice; the response was greater and prolonged in IL-10−/− mice. Muscle TNFα mRNA also increased, but without differences between genotypes. IL-6 protein concentrations were elevated by LPS with a greater and prolonged response for IL-10−/− mice, but TNFα did not change. These results provide the first in vivo evidence that endogenous IL-10 attenuates IL-6 expression by skeletal muscle in response to LPS.

Keywords: IL-6, IL-10, LPS, skeletal muscle, gastrocnemius

1. INTRODUCTION

Emerging data have clearly demonstrated physiologically significant autocrine and paracrine roles of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 that is released from skeletal muscle(Frost and Lang, 2005; Pedersen and Febbraio, 2005), such that it has been suggested to be a “myokine,” a cytokine released from muscle cells (Keller et al., 2001; Steensberg et al., 2000). Skeletal muscles also produce the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNFα (Frost et al., 2002; Phillips and Leeuwenburgh, 2005; Plomgaard et al., 2005), and the majority of data suggest that TNFα is a key contributor to muscle protein loss following infection. Factors that regulate IL-6 and TNFα expression in skeletal muscle continue to be elucidated, and the importance of identifying these factors is crucial since skeletal muscle comprises the largest organ system in the body (40–50% of body mass). Thus, skeletal muscle can play a pivotal role in both local and systemic responses to an inflammatory insult. A potentially important regulator of IL-6 and TNFα expression and release is IL-10, the prototypical anti-inflammatory cytokine that has been shown to suppress the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines by cells of the innate immune system (Moore et al., 2001). It was recently reported that the expression of TNFα and IL-1β in response LPS is significantly greater in the plasma and livers of IL-10−/− mice as compared to IL-10+/+ mice (Zhong et al., 2006). IL-6 and TNFα protein content are also increased in the brains of IL-10−/− mice as compared to IL-10+/+ controls (Agnello et al., 2000). While these data support the idea that IL-10 is an important regulator of both IL-6 and TNFα in response to an inflammatory stimuli, the potential role of IL-10 in regulating skeletal muscle-derived IL-6 or TNFα is unknown.

In response to LPS, skeletal muscle produces numerous cytokines including TNFα, IL-1β and IL-6 (Frost et al., 2002; Lang et al., 2003) which all have effects on muscle protein balance by affecting protein synthesis or degradation (Argiles et al., 2005; Frost and Lang, 2005). While TNFα and IL-1β display classic properties of pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-6 has both pro-and anti-inflammatory properties (Tilg et al., 1997). IL-6 has been implicated in muscle atrophy (Haddad et al., 2005) and muscle protein catabolism; however, increases in plasma IL-6 have been shown to increase expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines including IL-10 (Steensberg et al., 2003). Since evidence in other organs suggests that IL-10 deficiency increases the IL-6 response to LPS (Agnello et al., 2000; Zhong et al., 2006), it is intriguing to evaluate whether this also occurs in muscle. Further, IL-10 also contributes to inhibiting the TNFα response (de Waal Malefyt et al., 1991), but it is unknown whether loss of endogenous IL-10 would result in elevated levels of TNFα in skeletal muscle in response to an inflammatory insult.

Cytokine expression by muscle has striking systemic implications. For example, cytokine release from muscle during exercise has been directly linked to central fatigue (i.e. cytokine sickness) via their interaction with the central nervous system (Carmichael et al., 2006; Meeusen et al., 2006). Exaggerated pro-inflammatory cytokine release following intense exercise (± high heat), including release of IL-6, impacts the brain to cause mood disturbances, loss of energy, sleep disturbances, fever, depressed food and water intake, underperformance syndrome and an increased score on the sickness impact profile (Robson, 2003). Also, major depressive disorders can develop on a background of cytokine-induced sickness behavior (Dantzer, 2006; Dantzer and Kelley, 2007). A reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα directly correlates with the psychopathological improvement of patients with major depressive disorders (Lanquillon et al., 2000). Since, muscle is the largest organ in the body, elucidating the mechanisms that temper its pro-inflammatory cytokine response would provide useful information needed to control the central and systemic impact of muscle cytokines.

To date, no studies have reported how the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10, impacts expression of IL-6 or TNFα in skeletal muscle in response to an inflammatory insult. Systemic injection of IL-10 has been reported to promote inflammation in humans (reviewed in Scumpia and Moldawer, 2005) and i.p. injection of IL-10 exacerbates clinical symptoms of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice (Cannella et al., 1996). Here we avoided the problems associated with systemic injection of IL-10 by using a genetic model to assess the role of endogenous IL-10 in regulating muscle-derived IL-6 and TNFα. The primary objective of the present experiments was to test the hypothesis that the absence of endogenous IL-10 is associated with a greater in vivo IL-6 response in mouse skeletal muscle. The results confirm that skeletal muscle markedly increases expression of IL-6, less so for TNFα, in response to LPS and also reveal a dramatically enhanced expression of IL-6, but not TNFα, by skeletal muscle in the absence of endogenous IL-10.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental design

Adult (10–11 wk old), male, IL-10−/− (Jackson labs strain B6.129P2-Il10tm1Cgn/J) or the background wild-type (C57BL/J6) IL-10+/+ control mice were housed individually under specific pathogen-free conditions for 1 week after arrival. Mice were randomly assigned to one of the following groups (n = 4/group/genotype): 1) 4 h saline (excipient) control 2) 24 h saline control; 3) 4 h LPS; or 4) 24 h LPS. IL-10−/− mice were ‘Generation N10F33 (20-Dec-06), where N = the number of backcrosses. A strain is considered fully congenic after ten generations of backcrossing (N10). We first performed a dose-response experiment measuring the inflammatory response to several doses of LPS (0, 5, 10, and 25 μg/mouse; Sigma, serotype 0127:B8) given i.p. This experiment established that 25 μg of LPS would provide a robust stimulation of cytokine expression and would induce sickness, but without mortality or loss of muscle mass, even with IL-10−/− mice (data not shown). Therefore, LPS was dissolved in sterile saline and injected i.p. at a dose of 25 μg in 0.1 ml for the current study. Sterile saline was used as the vehicle control. Mice were euthanized 4 or 24 h post-injection by carbon dioxide inhalation and both gastrocnemius muscles were quickly removed, trimmed of excess fat and connective tissue, wet weighed, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80 °C. This time course allowed investigation of the response for both the acute and the early recovery periods (Kelley et al., 2003). At sacrifice, blood was drawn into ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-coated tubes and the resultant plasma was stored at −80 °C. All animal use protocols were approved by the Animal Use Committee at the University of Illinois and followed the American Physiological Society Animal Care Guidelines.

mRNA Analyses

Muscle samples (50–60 mg) were homogenized in 1 ml of TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH) and RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s protocol. DNAase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) treatment was performed according to manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentration was determined with a spectrophotometer and the RNA was stored at −80 °C. Quantitative real time RT-PCR was used to determine the expression of IL-6 and TNFα mRNA relative to β-actin. Total RNA (1 μg) from each muscle sample was reverse-transcribed using the Stratascript first strand synthesis system (Stratagene). A 1 μl aliquot of the reverse transcription product was added to a reaction mix containing 1× Full velocity™ SYBR® Green (Stratagene) and 150 nM of the IL-6, TNFα, or β-actin primer pairs. PCR were performed with a Stratagene Mx3000P with the following parameters: a denaturing step at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 10 s at 95 °C and 30 s at 60 °C. The primer sequences were as follows for β-actin: forward 5′-CTGGTCGTACCACAGGCATT-3′, reverse 5′-CTCTTTGATGTCACGCACGA-3′, IL-6: forward 5′-CTTGGGACTGATGCTGGTGA-3′, reverse 5′-TGCAAGTGCATCATCGTTGT-3′ and TNFα: forward 5′-ACCCCCTGAGTCTGCTCAAT-3′, reverse 5′-CCTGGTGGGACTTGGTTGTA-3′ (Operon, AL) and generated fragments of 209, 191, and 177 bp, respectively. Fluorescence measurements were taken at the end of each 60 °C product extension period. After amplification, a melting curve analysis was performed to verify amplification product specificity and absence of primer-dimer complexes. In initial experiments, PCR products were separated on 2% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide, and photographed under UV light to validate that the PCR products were the appropriate size and no artifact bands were present. All PCR reactions were performed in duplicate for each reverse transcription product. Relative expression of IL-6 and TNFα was normalized by subtracting the corresponding β-actin threshold cycle (CT) values and using the ΔΔCT comparative method (Schmittgen et al., 2000). β-actin CT values were not different across genotype, treatment or time. Data are expressed as fold changes relative to saline controls.

Protein Analyses

Gastrocnemius muscles were homogenized in 10 volumes of an ice-cold buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 2 mM potassium phosphate, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM ethyleneglycol bis(aminoethylether) tetraacetic acid, 10 % glycerol, 1 % Triton X-100, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 3 mM benzamidine, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 0mM leupeptin, 5 mg/ml aprotinin, and 1 mM 4-[(2-aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride] using a motor driven glass pestle. The homogenates were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 20 min at 4 °C and the supernatants were removed as the detergent-soluble fraction. Protein concentrations were determined using the BioRad Protein Assay with bovine serum albumin for the standard curve. Samples were stored in aliquots at −80 °C.

ELISA

IL-6 and TNFα concentrations were measured by validated kits (Endogen, IL) with detection limits of 7 and 9 pg, respectively. Plasma and muscle cytokine concentrations were expressed as pg/ml of plasma and pg/mg muscle protein, respectively.

Statistical Analyses

All data are presented as means ± SEM. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to assess main effects of genotype (IL-10+/+ vs. IL-10−/−), treatment (saline vs. LPS), time (hours post LPS) or interactions between genotype and treatment for all variables. If significant differences were found, the Bonferroni post-hoc test was used to determine the source of the difference. Since there were no significant differences between the saline-injected groups (4 vs. 24 h within strain), these data were pooled for a single saline control group. All analyses were performed with Graphpad Prism 4.0 with the significance level set at p<0.05.

3. RESULTS

Changes in body and muscle weight

Across all groups, initial body weights of the IL-10+/+ and IL-10−/− were not significantly different (22.1 ± 0.3 g vs. 21.5 ± 0.3 g, respectively). As expected, LPS depressed body weight even after 4 h of injection; an effect that was sustained at 24 h (Table 1). Although IL-10−/− mice have slightly smaller gastrocnemius muscle compared to wild-type controls, 25 μg LPS did not change muscle weight (Table 1). Muscle weights are frequently expressed relative to body weight (muscle weight/body weight) to determine if muscle size is specifically altered relative to all body tissues. Relative gastrocnemius muscle weight was not different between genotypes (5.59 ± 0.13 for IL-10+/+ versus 5.72 ± 0.03 mg/g IL-10−/−, p>0.05) and was not affected by LPS treatment (data not shown). These findings confirmed that we had chosen a dose of LPS that induces loss of body weight (we have previously noted that this same dose is associated with LPS-induction of sickness behavior and reduced food intake (Dantzer et al., 1998)). However, the dose of LPS lacked a cachexic effect on muscle, as hypothesized.

Table 1.

Body and muscle weights for IL-10+/+ and IL-10−/− mice following i.p. treatment with excipient or LPS.

| IL-10+/+ | IL-10−/− | |

|---|---|---|

| Body Weight (Δ, g) | ||

| Saline | 0.1 ± 0.1 | −0.1 ± 0.1 |

| 4 h post LPS | −0.7 ± 0.1 † | −0.8 ± 0.1 † |

| 24 h post LPS | −1.1 ± 0.1 † | −1.3 ± 0.1 † |

| Gastrocnemius Weight (mg) | ||

| Saline | 132 ± 2 | 120 ± 2 * |

| 4 h post LPS | 125 ± 4 | 121 ± 4 |

| 24 h post LPS | 126 ± 2 | 123 ± 3 |

Values are mean ± SEM

p<0.05 comparing IL-10+/+ and IL-10−/− within time

p<0.05 compared to saline within strain

Changes in muscle IL-6 and TNFα mRNA expression

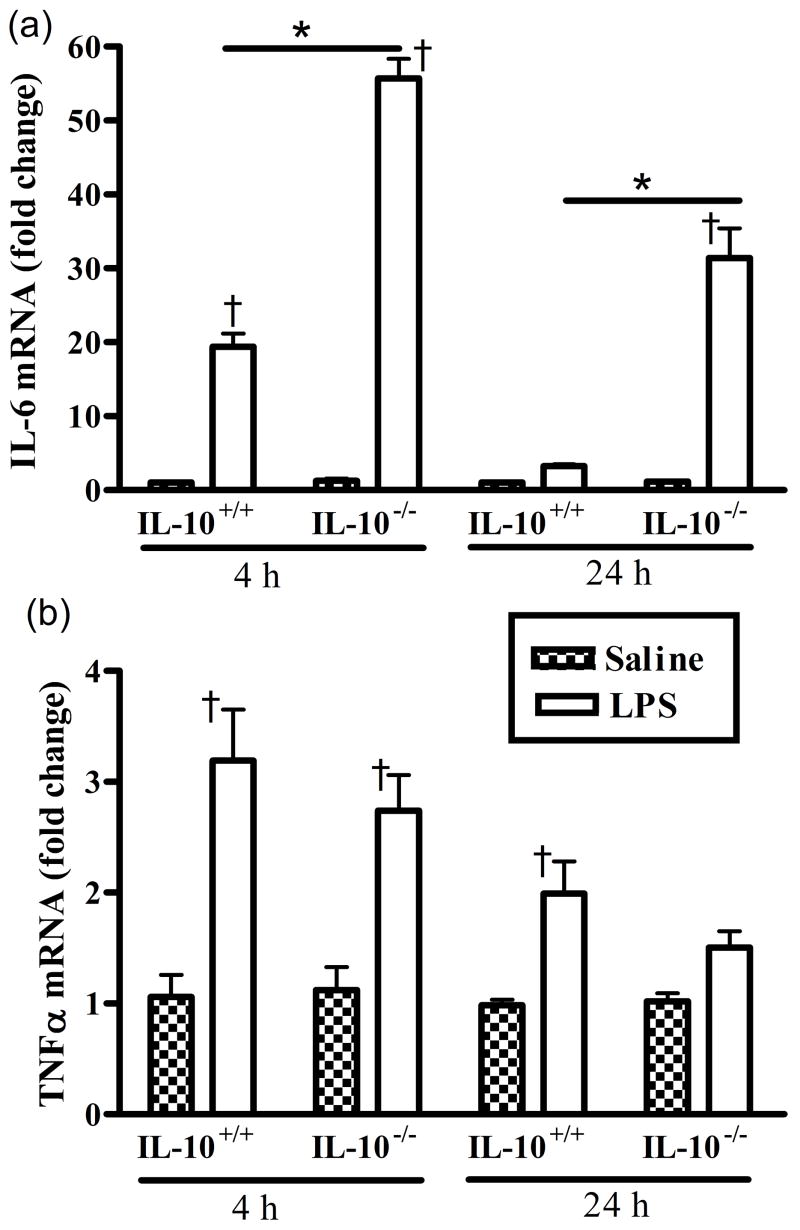

There were no significant genotype differences in IL-6 or TNFα mRNA between saline control groups, thus data are presented as fold changes following LPS relative to saline control for both cytokines. There were significant main effects of genotype and time (hours post LPS), and a significant interaction of genotype and time for the IL-6 mRNA response (Fig. 1a). The response to LPS was greater (p<0.05) in the IL-10−/− mice compared to the IL-10+/+ mice at both 4 and 24 h. IL-6 mRNA expression was markedly increased relative to the corresponding saline controls for both IL-10+/+ and IL-10−/− mice at 4 h post LPS, the response of IL-10−/− mice being more that twice that of the wild-type mice. After 24 h, IL-6 mRNA had returned to normal in wild-type muscles, but was still elevated by over 30-fold in muscles from IL-10−/− mice.

Figure 1.

LPS increases mRNA expression of both (a) IL-6 and (b) TNFα in gastrocnemius muscles of IL-10+/+ wild-type and IL-10−/− mice. Data are expressed as fold changes relative to control (set at 1.0 indicated by the dashed line). * p<0.05 comparing IL-10+/+ and IL-10−/− within time, † p<0.05 compared to corresponding saline control within genotype.

There was a significant main effect of time, but not genotype for TNFα mRNA expression (Fig. 1b). TNFα mRNA expression was slightly, but significantly, increased relative to the corresponding saline controls for both IL-10+/+ and IL-10−/− mice at 4 h post LPS. TNFα mRNA relative expression did not differ across genotype, but was still significantly increased in wild-type IL-10+/+ mice after 24 h.

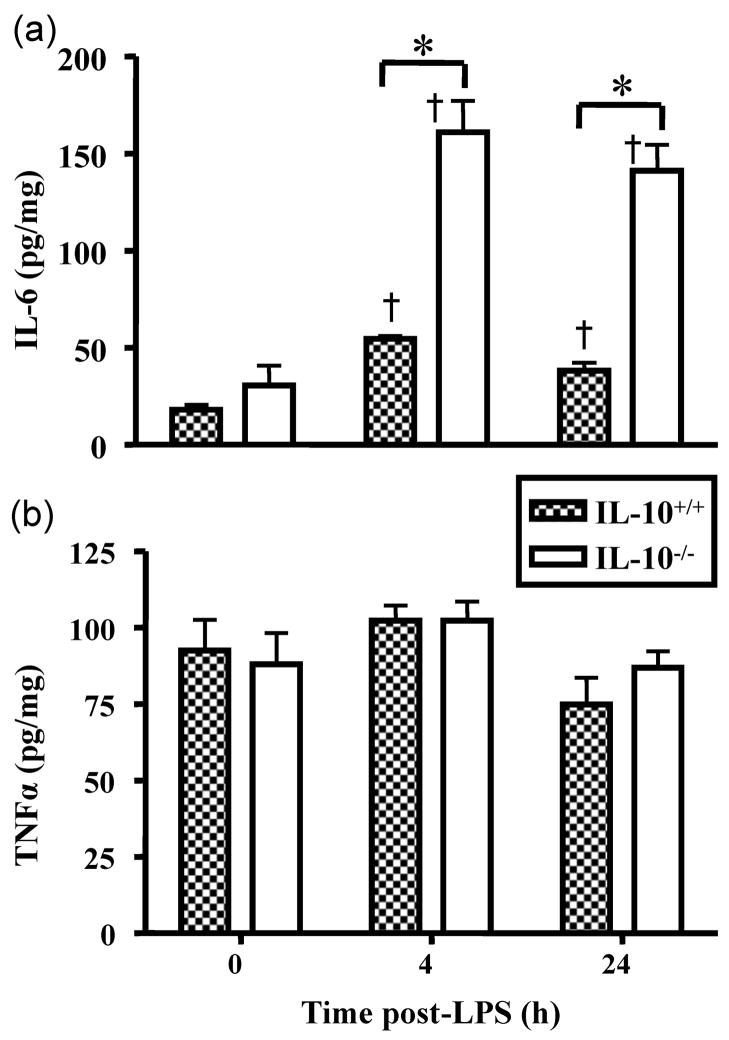

Changes in IL-6 and TNFα protein concentration

There were significant main effects of genotype and time and a significant interaction for the IL-6 concentrations in gastrocnemius muscle (Fig. 2a). IL-6 levels in saline-treated mice did not differ across genotype. IL-6 concentrations were significantly elevated 4 and 24 h post LPS injection in both IL-10+/+ and IL-10−/− mice. Muscle IL-6 concentrations were returning towards control levels for IL-10+/+ mice by 24 h post LPS, but IL-6 levels were still markedly increased at 24 h for IL-10−/− mice compared to wild-type mice. At both time points, muscle IL-6 concentrations were significantly greater in the IL-10−/− mice as compared to the IL-10+/+ mice. There were no significant effects of LPS, time or genotype on TNFα levels in skeletal muscle (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2.

LPS increases protein content of (a) IL-6 and (b) TNFα in gastrocnemius muscles of IL-10+/+ wild-type and IL-10−/− mice. * p<0.05 comparing IL-10+/+ and IL-10−/− within time, † p<0.05 compared to corresponding saline within genotype.

To determine if systemic cytokine concentrations paralleled muscle cytokine expression, IL-6 and TNFα were quantified in plasma. There were significant main effects of genotype and time and a significant interaction for the IL-6 concentrations in plasma (Table 2). Plasma IL-6 concentrations did not differ across phenotype for saline-treated mice. Similar to muscle, IL-6 concentrations were significantly elevated 4 h post LPS injection in both IL-10+/+ and IL-10−/− mice, but remained elevated at 24 h post LPS only in IL-10−/− mice. At both time points, the plasma IL-6 concentrations were significantly greater in the IL-10−/− mice as compared to the IL-10+/+ mice, paralleling the changes in muscle. There was a significant effect of time and genotype for TNFα plasma concentrations (Table 2). In the IL-10+/+ mice, TNFα was below assay detection limits following saline or LPS injection. In IL-10−/− mice, TNFα was not detected in saline-treated animals, but TNFα was significantly elevated 4 h post-LPS before returning to near baseline at 24 h.

Table 2.

Plasma IL-6 and TNFα for IL-10+/+ and IL-10−/ − mice following i.p. treatment with excipient or LPS.

| IL-10+/+ | IL-10−/ − | |

|---|---|---|

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | ||

| Saline | 13 ± 2 | 18 ± 2 |

| 4 h post LPS | 5617 ± 389 † | 7673 ± 355 *,† |

| 24 h post LPS | 19 ± 2 | 3471 ± 276 *,† |

| TNFα (pg/ml) | ||

| Saline | ND | ND |

| 4 h post LPS | ND | 403 ± 40 *,† |

| 24 h post LPS | ND | 14 ± 4 |

Values are mean ± SEM, ND, not detectable

p<0.05 comparing IL-10+/+ and IL-10−/ − within time

p<0.05 compared to saline within strain

4. DISCUSSION

These results provide the first in vivo evidence that IL-10 is an important regulator of skeletal muscle IL-6 expression following an acute inflammatory stimulus. The absence of IL-10 was associated with significantly greater IL-6 mRNA and protein expression in the gastrocnemius which parallels the elevated IL-6 concentrations in the plasma. IL-10 deficiency increased muscle and plasma IL-6 in the acute inflammatory phase and markedly extended the elevation of this cytokine. In the muscle of IL-10+/+ mice, IL-6 mRNA levels had returned to control values by 24 h, while in IL-10−/− mice, IL-6 expression at 24 h had only slightly decreased compared to levels at 4 h. The significance of these findings is underscored by the large contribution of muscle to total body mass and that muscle-derived IL-6 can act in both an autocrine fashion (Keller et al., 2003) and can be released into the plasma to exert systemic effects (Febbraio and Pedersen, 2002; Pedersen et al., 2001; Steensberg et al., 2000). These findings strongly support our hypothesis that endogenous IL-10 is tempering pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion by skeletal muscle.

The striking (20 to 50 fold) rise in steady-state IL-6 mRNA that occurred within 4 h of LPS injection indicates that increases in gene transcription likely contributed to the elevations in IL-6 protein in the gastrocnemius and probably the plasma. Previous work has reported up to a 106-fold increase in IL-6 mRNA after LPS treatment (Frost et al., 2002); however, a greater response as compared to the present findings were not surprising due to differences in time of tissue collection post LPS injection, LPS dose, and mouse strain. Frost and colleagues used a 10-fold higher LPS dose, collected muscle at an earlier time point (2 h) and used C3H/HeSnJ mice. In addition, they utilized ribonuclease protection assays to quantify mRNA which yielded very low baseline transcript levels thus resulting in a large fold increase relative to baseline (Frost et al., 2002). Similar to the prolonged increase of IL-6 protein in the absence of IL-10, IL-6 mRNA at 24 h dropped only 33 % from 4 to 24 h post-LPS in muscles from IL-10−/− mice as compared to an 87 % drop in muscles of IL-10+/+ mice. Thus, in the absence of IL-10, the increases in IL-6 expression are not attenuated and perhaps they may be accentuated by a positive auto-regulatory role of IL-6 in skeletal muscle (Keller et al., 2003).

These studies were initiated in response to a growing recognition of the interaction between muscle and the brain. We recently published evidence that IL-6 secretion by cultured muscle cells is suppressed by IL-10 (Strle et al., 2007) confirming this proto-typical anti-inflammatory role of IL-10 that was initially described in other systems. We had also shown that IL-10 blocks LPS-induced sickness behavior of mice (Bluthe et al., 1999). Along with the age-dependent decline in endogenous IL-10 that is directly linked to elevated endogenous brain IL-6 expression (Ye and Johnson, 2001), we wanted to determine if endogenous IL-10 inhibited the expression of IL-6 within muscle. Clearly this is the case. The current study forms a basis for future work to define the role of pro-and anti-inflammatory cytokine secretion from skeletal muscle on central function and in particular on sickness and depressive-like behaviors. Although it is clear that pro-inflammatory cytokines from muscle have a systemic role (Febbraio and Pedersen, 2002; Pedersen et al., 2001; Steensberg et al., 2000) it awaits determination as to the impact of muscle IL-6 on behavioral changes associated with infection.

In contrast, to the marked differences in IL-6 between genotypes, the only difference between genotypes for TNFα was observed in the plasma. In all plasma samples from IL-10+/+ mice and saline-injected IL-10−/− mice, TNFα concentrations were below assay detection limits. The absence of a rise in plasma or muscle TNFα protein in the present study suggests that our low dose of LPS, which was specifically selected not have a systemic cachexic response, was inadequate to overcome the anti-inflammatory action of IL-10 in wild-type mice. In IL-10−/− mice, plasma TNFα was significantly elevated 4 h post-LPS before returning to near baseline at 24 h. Although LPS did increase TNFα mRNA in the gastrocnemius muscle in both wild-type and IL-10−/− mice, this small 1-fold increase was clearly not adequate to increase muscle levels of the cytokine.

Steady state TNFα mRNA was significantly increased in response to LPS in both genotypes, however, the magnitude of the responses were much smaller than that found with IL-6. This is not unexpected based upon previously reported differences in the TNFα vs. IL-6 mRNA responses in skeletal muscle. For example, in mouse skeletal muscle, TNFα and IL-6 mRNA were increased 9.5- and 106-fold, respectively, 2 h following LPS injection (Frost et al., 2002). A smaller rise in TNFα as compared to IL-6 mRNA in response to LPS has also been reported in rat skeletal muscle (Lang et al., 2003) wherein TNFα and IL-6 mRNA were increased ~10- and ~75-fold, respectively following LPS administration. Finally, IL-6 mRNA expression appears to be more sensitive to LPS than TNFα mRNA as significant increases in TNFα mRNA in rat skeletal muscle were not apparent until the highest LPS dose of 1000 μg/kg while increases in IL-6 mRNA were evident at 10, 100, and 1000 μg/kg doses (Lang et al., 2003).

It is now clear that skeletal muscle dramatically increases its synthesis of IL-6 in response to stimuli as diverse as LPS (Frost et al., 2002; Lang et al., 2003) and exercise (Keller et al., 2001; Pedersen and Febbraio, 2005; Steensberg et al., 2000). This is supported by our recent report that a clonal population of murine C2C12 muscle cells, that do not contain macrophages or neutrophils, synthesize abundant amounts of IL-6 and that IL-6 production is inhibited by IL-10 (Strle et al., 2007). Similarly IL-6 secretion by cultured muscle cells is directly increased by LPS (Frost et al., 2003; Frost et al., 2006). Evidence suggests that this elevation in muscle IL-6 contribute to muscle atrophy, even in healthy animals (Haddad et al., 2005).

Similarly, TNFα is considered to be pro-inflammatory and is implicated in muscle wasting (Frost and Lang, 2005). Skeletal muscle fibers have been shown to produce TNFα in a fiber type specific manner in both humans (Plomgaard et al., 2005) and rats (Phillips and Leeuwenburgh, 2005). TNFα is associated with accelerated skeletal muscle protein loss both in vitro (Li and Reid, 2000) and in vivo (Flores et al., 1989; Goodman, 1991). In the present study, we found that the absence of IL-10 was associated with a significantly greater plasma TNFα response, but that this did not extend to an increase in skeletal muscle content of TNFα. Thus, further investigation is necessary to determine if IL-10 deficiency may increase skeletal muscle TNFα expression in response to LPS but that such a response may require higher doses of LPS.

The novelty of the present results is that an in vivo genetic model was used to demonstrate that IL-10 is an important physiological regulator of skeletal muscle IL-6 expression. Further, the regulatory role of IL-10 on IL-6 in skeletal muscle is not limited to only the acute phase of the inflammatory response, but is evident up to 24 hours after LPS injection. These results clearly demonstrate the importance of anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10, in regulating both systemic and muscular responses to inflammatory stimuli.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH RO3 AR049855 to KAH, R01 AG 023580 to R.W. Johnson, USDA AG 2004-35206-14144 to RHM and NIH RO1 AI 50442 to KWK.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agnello D, Villa P, Ghezzi P. Increased tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 production in the central nervous system of interleukin-10-deficient mice. Brain Res. 2000;869:241–243. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argiles JM, Busquets S, Lopez-Soriano FJ. The pivotal role of cytokines in muscle wasting during cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:2036–2046. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluthe RM, Castanon N, Pousset F, Bristow A, Ball C, Lestage J, Michaud B, Kelley KW, Dantzer R. Central injection of IL-10 antagonizes the behavioural effects of lipopolysaccharide in rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1999;24:301–311. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(98)00077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canella B, Gao YL, Brosnan C, Raine CS. IL-10 fails to abrogate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neurosci Res. 1996;45:735–746. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19960915)45:6<735::AID-JNR10>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael MD, Davis JM, Murphy EA, Brown AS, Carson JA, Mayer EP, Ghaffar A. Role of brain IL-1beta on fatigue after exercise-induced muscle damage. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R1344–1348. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00141.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R. Cytokine, sickness behavior, and depression. Neurol Clin. 2006;24:441–460. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, Bluthe RM, Gheusi G, Cremona S, Laye S, Parnet P, Kelley KW. Molecular basis of sickness behavior. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;856:132–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, Kelley KW. Twenty years of research on cytokine-induced sickness behavior. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Waal Malefyt R, Abrams J, Bennett B, Figdor CG, de Vries JE. Interleukin 10(IL-10) inhibits cytokine synthesis by human monocytes: an autoregulatory role of IL-10 produced by monocytes. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1209–1220. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.5.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Febbraio MA, Pedersen BK. Muscle-derived interleukin-6: mechanisms for activation and possible biological roles. Faseb J. 2002;16:1335–1347. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0876rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores EA, Bistrian BR, Pomposelli JJ, Dinarello CA, Blackburn GL, Istfan NW. Infusion of tumor necrosis factor/cachectin promotes muscle catabolism in the rat. A synergistic effect with interleukin 1. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1614–1622. doi: 10.1172/JCI114059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RA, Lang CH. Skeletal muscle cytokines: regulation by pathogen-associated molecules and catabolic hormones. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2005;8:255–263. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000165003.16578.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RA, Nystrom GJ, Lang CH. Lipopolysaccharide regulates proinflammatory cytokine expression in mouse myoblasts and skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;283:R698–709. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00039.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RA, Nystrom GJ, Lang CH. Lipopolysaccharide and proinflammatory cytokines stimulate interleukin-6 expression in C2C12 myoblasts: role of the Jun NH2-terminal kinase. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R1153–1164. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00164.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RA, Nystrom GJ, Lang CH. Multiple Toll-like receptor ligands induce an IL-6 transcriptional response in skeletal myocytes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R773–784. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00490.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman MN. Tumor necrosis factor induces skeletal muscle protein breakdown in rats. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:E727–730. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1991.260.5.E727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad F, Zaldivar F, Cooper DM, Adams GR. IL-6-induced skeletal muscle atrophy. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:911–917. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01026.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller C, Steensberg A, Pilegaard H, Osada T, Saltin B, Pedersen BK, Neufer PD. Transcriptional activation of the IL-6 gene in human contracting skeletal muscle: influence of muscle glycogen content. Faseb J. 2001;15:2748–2750. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0507fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller P, Keller C, Carey AL, Jauffred S, Fischer CP, Steensberg A, Pedersen BK. Interleukin-6 production by contracting human skeletal muscle: autocrine regulation by IL-6. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;310:550–554. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley KW, Bluthe RM, Dantzer R, Zhou JH, Shen WH, Johnson RW, Broussard SR. Cytokine-induced sickness behavior. Brain Behav Immun. 2003;17 Suppl 1:S112–118. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(02)00077-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang CH, Silvis C, Deshpande N, Nystrom G, Frost RA. Endotoxin stimulates in vivo expression of inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-1beta, -6, and high-mobility-group protein-1 in skeletal muscle. Shock. 2003;19:538–546. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000055237.25446.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanquillon S, Krieg JC, Bening-Abu-Shach U, Vedder H. Cytokine production and treatment response in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22:370–379. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YP, Reid MB. NF-kappaB mediates the protein loss induced by TNF-alpha in differentiated skeletal muscle myotubes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;279:R1165–1170. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.4.R1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeusen R, Watson P, Dvorak J. The brain and fatigue: new opportunities for nutritional interventions? J Sports Sci. 2006;24:773–782. doi: 10.1080/02640410500483022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O’Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen BK, Febbraio M. Muscle-derived interleukin-6--a possible link between skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, liver, and brain. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19:371–376. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen BK, Steensberg A, Schjerling P. Muscle-derived interleukin-6: possible biological effects. J Physiol. 2001;536:329–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0329c.xd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips T, Leeuwenburgh C. Muscle fiber specific apoptosis and TNF-alpha signaling in sarcopenia are attenuated by life-long calorie restriction. Faseb J. 2005;19:668–670. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2870fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomgaard P, Penkowa M, Pedersen BK. Fiber type specific expression of TNF-alpha, IL-6 and IL-18 in human skeletal muscles. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2005;11:53–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson P. Elucidating the unexplained underperformance syndrome in endurance athletes : the interleukin-6 hypothesis. Sports Med. 2003;33:771–781. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200333100-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen TD, Zakrajsek BA, Mills AG, Gorn V, Singer MJ, Reed MW. Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction to study mRNA decay: comparison of endpoint and real-time methods. Anal Biochem. 2000;285:194–204. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scumpia PO, Moldawer LL. Biology of interleukin-10 and its regulatory roles in sepsis syndromes. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:S468–S471. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000186268.53799.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steensberg A, Fischer CP, Keller C, Moller K, Pedersen BK. IL-6 enhances plasma IL-1ra, IL-10, and cortisol in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;285:E433–437. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00074.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steensberg A, van Hall G, Osada T, Sacchetti M, Saltin B, Klarlund Pedersen B. Production of interleukin-6 in contracting human skeletal muscles can account for the exercise-induced increase in plasma interleukin-6. J Physiol 529 Pt. 2000;1:237–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00237.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strle K, RH MCC, Tran L, King A, Johnson RW, Freund GG, Dantzer R, Kelley KW. Novel activity of an anti-inflammatory cytokine: IL-10 prevents TNFalpha-induced resistance to IGF-I in myoblasts. J Neuroimmunol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilg H, Dinarello CA, Mier JW. IL-6 and APPs: anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive mediators. Immunol Today. 1997;18:428–432. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye SM, Johnson RW. An age-related decline in interleukin-10 may contribute to the increased expression of interleukin-6 in brain of aged mice. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2001;9:183–192. doi: 10.1159/000049025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong J, Deaciuc IV, Burikhanov R, de Villiers WJ. Lipopolysaccharide-induced liver apoptosis is increased in interleukin-10 knockout mice. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1762:468–477. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]