Abstract

Increased expression of the serine protease urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) in tumor tissues is highly correlated with tumor cell migration, invasion, proliferation, progression, and metastasis. Thus inhibition of uPA activity represents a promising target for antimetastatic therapy. So far, only the x-ray crystal structure of uPA inactivated by H-Glu-Gly-Arg-chloromethylketone has been reported, thus limited data are available for a rational structure-based design of uPA inhibitors. Taking into account the trypsin-like arginine specificity of uPA, (4-aminomethyl)phenylguanidine was selected as a potential P1 residue and iterative derivatization of its amino group with various hydrophobic residues, and structure–activity relationship-based optimization of the spacer in terms of hydrogen bond acceptor/donor properties led to N-(1-adamantyl)-N′-(4-guanidinobenzyl)urea as a highly selective nonpeptidic uPA inhibitor. The x-ray crystal structure of the uPA B-chain complexed with this inhibitor revealed a surprising binding mode consisting of the expected insertion of the phenylguanidine moiety into the S1 pocket, but with the adamantyl residue protruding toward the hydrophobic S1′ enzyme subsite, thus exposing the ureido group to hydrogen-bonding interactions. Although in this enzyme-bound state the inhibitor is crossing the active site, interactions with the catalytic residues Ser-195 and His-57 are not observed, but their side chains are spatially displaced for steric reasons. Compared with other trypsin-like serine proteases, the S2 and S3/S4 pockets of uPA are reduced in size because of the 99-insertion loop. Therefore, the peculiar binding mode of the new type of uPA inhibitors offers the possibility of exploiting optimized interactions at the S1′/S2′ subsites to further enhance selectivity and potency. Because crystals of the uPA/benzamidine complex allow inhibitor exchange by soaking procedures, the structure-based design of new generations of uPA inhibitors can rely on the assistance of x-ray analysis.

Keywords: urokinase-type plasminogen activator, x-ray crystal structure

Tumor cell invasion and metastasis strongly depend on the regulated expression of proteolytic enzymes involved in degradation of the surrounding extracellular matrix (ECM) and in dissociation of cell–cell and/or cell–matrix contacts (1–4). One of these enzymes, the urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA), converts plasminogen into plasmin, a protease with a wide activity spectrum that digests various ECM components, e.g., fibronectin, laminin, and collagen type IV, and activates pro-enzyme forms of matrix metalloproteinases (5). Tumor cells direct the proteolytic activity of uPA, secreted by tumor cells or surrounding stromal cells, to the cell surface via a specific receptor (uPAR, CD87) (6). On binding to uPAR, uPA retains its enzymatic activity, and the rate of conversion of cell surface-associated plasminogen to plasmin is several-fold enhanced. In fact, binding of active uPA to the tumor cell surface via uPAR represents a crucial event for tumor cell proliferation and invasion as well, evidenced by the inhibitory action of compounds that abrogate uPA activity or block uPA/uPAR interaction (for reviews, see refs. 1 and 2). Thus, uPA plays a central role in pericellular proteolysis. Correspondingly, elevated antigen and activity levels of uPA are found in tumor tissues of cancer patients, and a statistically independent prognostic impact has been attributed to uPA in different malignancies (1–3, 7). The strong correlation between increased expression of uPA in tumor cells and the malignant phenotype is substantiated further by the finding that uPA overproduction results in an enhanced cancer cell invasiveness and metastasis (8).

Because the uPA system represents an attractive target for tumor therapy, various approaches have been attempted to interfere with the expression or activity of uPA and uPAR at the gene or protein level, including the application of antisense oligonucleotides or RNA, antibodies, recombinant or synthetic uPA, or uPAR binding-site fragments, as well as synthetic uPA active-site inhibitors (1, 2, 9). However, compared with the many reversible synthetic inhibitors reported for serine proteases such as thrombin and factor Xa (fXa) (10, 11), only a few selective low-molecular-weight uPA inhibitors are presently known (12). The common structural feature of uPA inhibitors is an aromatic moiety substituted with an amidino or guanidino function that as arginine–mimetic compounds are expected to bind to Asp-189 in the arginine-specific S1 pocket of uPA. Compounds that exhibit inhibition constants in the low micromolar range belong to substituted benzamidines and β-naphthamidines, amidinoindoles, and 5-amidino-benzimidazoles, as well as to mono-substituted phenylguanidines. Most of these compounds, however, display little or no selectivity for uPA and thus were found also to inhibit related enzymes like trypsin, thrombin, fXa, or plasmin (12–17). With some of these inhibitors, e.g., (4-amino)benzamidine, benzamidine or amiloride, an inhibition of tumor growth and even angiogenesis has been reported (18, 19). At present, the most potent and selective uPA inhibitors are the benzo[b]thiophen-2-carboxamidines B428 and B623, with Ki values of 0.53 μM and 0.16 μM, respectively (20). It has been demonstrated that these compounds inhibit uPA-mediated processes such as proteolytic degradation of the extracellular matrix as well as in vitro tumor cell adhesion, migration, and invasion. Furthermore, in in vivo studies a remarkable decrease in tumor growth and invasiveness was observed (21–24).

A rational structure-based design of reversible uPA inhibitors is severely hampered by the lack of a sufficiently large set of crystallographic data of uPA/inhibitor complexes; in fact, only the x-ray crystal structure of uPA inactivated by the suicide substrate H-Glu-Gly-Arg-CMK at 2.5 Å has been reported so far (25), possibly because of the difficulties in crystallization of this enzyme.

In the present study, a new class of nonpeptidic highly selective and reversible uPA inhibitors was identified by an iterative derivatization approach followed by a structure–activity relationship-based optimization that led to N-(1-adamantyl)-N′-(4-guanidinobenzyl)urea (WX-293T), which exhibits micromolar inhibition potency. Displacement of benzamidine from crystals of the B-chain-uPA/benzamidine complex (E. Zeslawska, A. Schweinitz, A. Karcher, P. Sondermann, R. H. & U. J., unpublished work) with WX-293T was successful, thus allowing the x-ray structure analysis of the uPA/inhibitor complex at 1.8 Å resolution. It revealed an unexpected binding of the inhibitor across the active site with interactions at both the S1 and S1′ subsites, thus yielding precious structural information for further improvements of potency and selectivity of this promising new type of uPA inhibitors. Because WX-293T exerts little cell toxicity even at high concentrations (up to 40-fold above its Ki-value toward uPA), this compound may represent an attractive lead structure for the development of potent antimetastatic drugs.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis of the Inhibitors.

For the synthesis of the (4-aminomethyl)phenylguanidine derivatives listed in Tables 1–3, the alkylamino group was selectively protected as tert-butyloxycarbonyl (Boc)- or benzyloxycarbonyl (Z)-derivative by exploiting its higher reactivity vs. the aniline function. Subsequent guanidinylation of the aromatic amino group was performed with N,N′-dibenzyloxycarbonyl-N"-triflylguanidine (26) or with N,N′-di-Boc-1-guanylpyrazole (27) in view of a selective amino-/guanidino-protection that takes into account the stability of the amino derivatives toward hydrogenolytic cleavage of the Z- or toward acid treatments for cleavage of the Boc groups in the final deprotection step. Unprotected (4-aminomethyl)-phenylguanidine was used only for the preparation of the thiourea 19 by reaction with 1-adamantylisothiocyanate. Similar guanidinylation and protection procedures were applied for the synthesis of compounds 2, 3, 8, and 9. N-acylation of the suitably guanidino-protected (4-amino)phenylguanidine, (4-aminomethyl)phenylguanidine, (3-aminomethyl)phenylguanidine and d,l-(4-guanidino)phenylalanine methyl ester with (Boc)2O, Boc-Gly-OH and sulfonyl chlorides was performed according to standard procedures. The urethanyl derivatives reported in Table 2 were obtained by reacting suitably guanidino-protected (4-aminomethyl)phenylguanidine derivatives with the commercially available ethyl-, 1-adamantyl-, benzyl-, (2-nitro-4,5-dimethoxy)benzyl-chloroformate, and with (4-phenylazo)benzyl-chloroformate (28). The compounds 16, 22 and 23 (Table 3) were prepared by acylation of (4-aminomethyl)phenyl-2,3-di-Z-guanidine with (1-adamantyl)acetyl chloride, 1-adamantane-carboxylic acid chloride, and benzoyl chloride, whereas compound 18 was obtained by acylation of 1-aminoadamantane with 3-[4-(2,3-di-Z-guanidino)phenyl]propanoic acid via 1-hydroxy-1H-benzotriazole/O-(benzotriazole-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium-tetrafluoroborate. The urea derivatives 17, 20, and 21 were obtained by reaction of (4-aminomethyl)phenyl-2,3-di-Z-guanidine with 1-adamantyl-, phenyl-, and naphtyl-isocyanate, respectively. The di-Z-guanidino-intermediates were deprotected by hydrogenolysis over Pd/C and the di-Boc-guanidino-intermediates by exposure to 95% trifluoroacetic acid. For analytical characterization of the compounds, HPLC and electrospray ionization (ESI)–MS were used, e.g., N-(1-adamantyl)-N′-(4-guanidinobenzyl)urea (WX-293T): HPLC [ET 125/4 Nucleosil 100/C18 columns (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany); linear gradient of MeCN/2% H3PO4 from 5:95 (i) to 90:10 (ii) in 13 min]: retention time 8.6 min; ESI-MS: m/z = 342 [M + H]+, Mr = 341.2 calculated for C19H27N5O1.

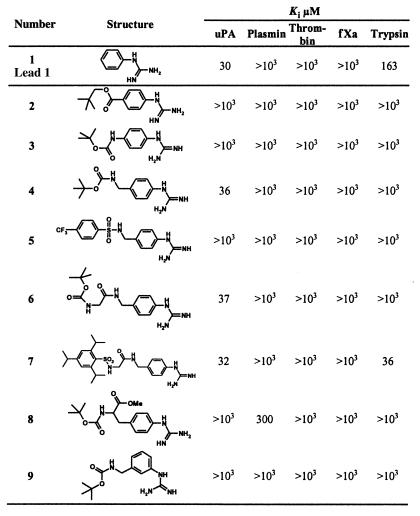

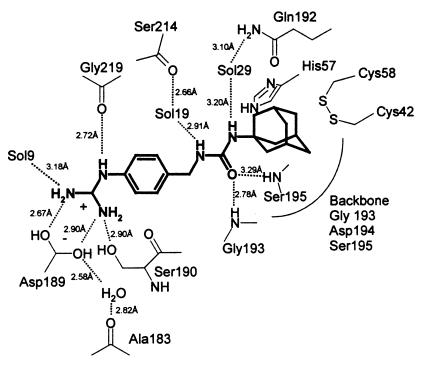

Table 1.

SAR of phenylguanidine derivatives as inhibitors of human uPA and their selectivity vs. other trypsin-like enzymes

Only acyl derivatives of 4-aminomethyl-phenylguanidine retain the inhibitory potency of phenylguanidine itself.

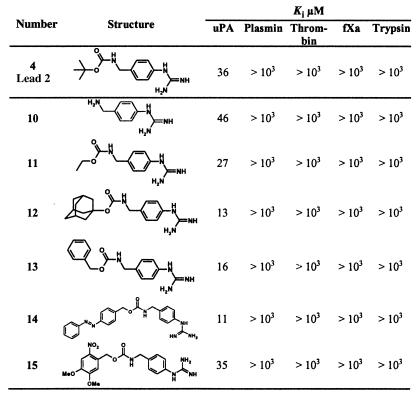

Table 2.

SAR of urethanyl derivatives of (4-aminomethyl)-phenylguanidine as uPA inhibitors: optimization of the hydrophobic moiety in terms of potency and selectivity

Table 3.

Atomic positional scanning of the spacer group in (4-aminomethyl)phenylguanidine derivatives as hydrogen bond donor/acceptor

Enzyme Assays.

The enzyme assays with bovine pancreatic trypsin, bovine thrombin, bovine fXa, human plasmin, human uPA, and single chain tissue PA (tPA) were performed as described previously (29). The Ki values were calculated by using a linear regression program, and the reported Ki values are means from at least three determinations.

X-Ray Structure Analysis.

Truncated recombinant human urokinase consisting of the complete B-chain of activated uPA [called βc-uPA; containing residues Ile-16 (178) to Leu-250 (424) by using the chymotrypsinogen nomenclature (25), with the sequence of full-length urokinase given in brackets] was prepared by expressing the sc-uPA gene including the mutation C122S (292) in Escherichia coli, refolding from inclusion bodies, and activating the inactive material under loss of the short A-chain as described elsewhere (E. Zeslawska, A. Schweinitz, A. Karcher, P. Sondermann, R.H. & U.J., unpublished work). This active βc-uPA was crystallized from a 1 M Li2SO4/0.8 M (NH4)2SO4/0.1 M sodium citrate solution (pH 5.2) in the presence of 6 mM benzamidine at 4°C. (E. Zeslawska, A. Schweinitz, A. Karcher, P. Sondermann, R.H. & U.J., unpublished work). The crystal of dimensions 0.1 × 0.08 × 0.25 mm3 diffracted to Bragg spacings beyond 1.7 Å. The bound benzamidine was replaced by WX-293T (compound 17; Table 3) by soaking the crystals in a suspension of 17 in 1.25 M Li2SO4/1 M (NH4)2SO4/0.125 M sodium citrate pH 5.2 at 4°C for 1 wk.

X-ray diffraction data to 1.8 Å (Table 4) of soaked crystals mounted in glass capillaries were collected at 16°C on a 350-mm MAR-Research (Hamburg, Germany) image plate detector attached to a Rigaku RU 200 rotating anode x-ray generator by using graphite monochromatized CuKα radiation. The densities were integrated, scaled, and converted to amplitudes by using routines from the ccp4 (30) program suite (Table 4). The refined model of benzamidine containing βc-uPA (E. Zeslawska, A. Schweinitz, A. Karcher, P. Sondermann, R.H. & U.J., unpublished work) was used for calculating initial Fo − Fc and 2Fo − Fc Fourier maps. The difference map contoured at 2.5 σ showed clear difference density for the complete inhibitor. This βc-uPA/inhibitor model was subjected to crystallographic refinement cycles with cns (31) by using the Engh and Huber (32) geometric restraints. The force field constants revealed from the energy-minimized inhibitor model were set to 10%. The structure was improved by alternating cycles of manual model building on a Silicon Graphics (Mountain View, CA) workstation with o (33) and by positional and B-factor refinement with bulk solvent correction with cns (31). At stereochemically reasonable sites with densities and difference densities above 1.0 σ and 2.5 σ, water molecules were added. This model converged to an R factor/R free of 20.0/24.0. The final refinement statistics are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Data collection and refinement statistics for the x-ray crystal structure of the uPA/inhibitor 17 (WX-293T) complex

| Data collection statistics | |

|---|---|

| Space group | P212121 |

| Cell constants | a = 52.85 Å, b = 54.77 Å, c = 81.58 Å |

| α = β = γ = 90° | |

| Resolution with data completeness of 60% | 1.8 Å |

| Multiplicity | 2.3 |

| Completeness (overall/2.0 Å/1.8 Å) | 84%/93%/60% |

| R merge (overall/2.0 Å/1.8 Å) | 8.7%/20%/56% |

| Refinement statistics | |

| Resolution range used in refinement | 500.0–1.8 Å |

| No. unique reflections | 20187 |

| R factor | 20.0% |

| R free (5% of the reflections not used in the refinement) | 24.0% |

| rmsd bond length | 0.005 Å |

| rmsd angle | 1.2° |

| rmsd bonded B factors, Å2 | 4.4 |

| Molecules in the asymmetric unit | 1 |

| Protein (no. heavy atoms/average B factor) | 1952/33.3 |

| Inhibitor (no. heavy atoms/average B factor) | 25/24.3 |

| Solvent (no. heavy atoms/average B factor) | 162/53.3 |

| Sulfate ions (no. heavy atoms/average B factor) | 1/52.0 |

rmsd, rms deviation.

Cell Proliferation Assay.

The cytotoxicity of inhibitor 17 (WX-293T) was tested with the human carcinoma cell lines OV-MZ-6 (34), MDA-MB-231, and A431 (both from the American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) by using the CellTiter 96 NonRadioactive Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (Promega), according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Cells were maintained at 37°C in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 10 mM Hepes (all from GIBCO), 100 units penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Biochrom, Berlin). A431 cell culture medium was supplemented with 200 μM l-glutamine (GIBCO). Increasing concentrations of inhibitor 17 (0–1000 μM) or vehicle control (PBS + EtOH) were applied to cell lines OV-MZ-6, MDA-MB-231, or A431 and the cells cultivated for another 48 h. After incubation with the chromogenic solution, the rate of formazan dye formation was determined by measuring the absorbance (560 nm − 640 nm). The 560 nm − 640 nm reading value is directly proportional to the number of living cells.

Results

Design of the (4-Aminomethyl)phenylguanidine-Based uPA Inhibitors.

The human urokinase is a trypsin-like arginine-specific serine protease. Correspondingly, arginine–mimetic compounds represent the most suitable partners for specific electrostatic interaction with the Asp-189 residue located at the bottom of the S1 pocket (25). To identify, among the large set of arginine-mimicking residues, the most suitable one for interaction with the uPA S1 subsite, in the first instance the simple compounds benzamidine, phenylguanidine, benzylcarbamidine, and benzylguanidine were analyzed for their ability to inhibit uPA. In full agreement with a previous report (16), phenylguanidine was found to inhibit uPA with remarkable selectivity and potency (Ki = 30 μM), whereas benzamidine was significantly less potent (Ki = 81 μM) and, more importantly, less selective. Surprisingly, benzylcarbamidine, as the isoster of phenylguanidine, and benzylguanidine were fully inactive toward uPA.

According to the x-ray structure of uPA (25), the space available for P2 substrate residues is severely limited by the insertion of Tyr-97A and Leu-97B if compared with other serine proteases such as trypsin or thrombin, and thus only small-sized amino acid side chains are accepted, preferably glycine (35). The insertion limits also the size of the hydrophobic S3/S4 subsites. In view of these structural properties of the substrate-binding cleft of uPA, phenylguanidine derivatives were synthesized that differed in the length of the P2 spacer and in the nature of the hydrophobic residue as potential interacting partner at the S3/S4 cavity (Table 1). Only the acyl derivatives 4, 6, and 7 of (4-aminomethyl)phenylguanidine were found to retain the inhibitory potency of phenylguanidine itself. Although Nα-sulfonyl derivatives of (3-amidino)phenylalanine have been shown to inhibit several trypsin-like serine proteases, uPA included (17), the sulfonyl derivative 5 and the (4-guanidino)phenylalanine derivative 8 as well as the derivative of (3-aminomethyl)phenylguanidine 9 were fully inactive toward uPA.

To investigate further the effect of the hydrophobic moiety on uPA inhibition, 4-(N-Boc-aminomethyl)phenylguanidine (4) was chosen as the lead compound. Parallel synthesis of a large number of diversomers of the urethanyl-type derivatives of (4-aminomethyl)phenylguanidine led to the compounds listed in Table 2 as the most potent inhibitors, with Ki values ranging between 11 and 36 μM. The results clearly suggest that the hydrophobic residues affect the uPA inhibition to much weaker extents than the spacer. Most importantly, inhibition of plasmin, thrombin, fXa, or trypsin in most cases was not detectable at concentrations up to 1,000 μM.

To optimize the hydrogen-bonding potential of the urethane spacer, the different oxygen and accordingly nitrogen atoms of the spacer were iteratively substituted by atoms with opposite or no hydrogen-bonding potential (Table 3). Because of the commercial availability of the reagents as well as the relatively good Ki value (13 μM), 4-(N-adamantyloxycarbonyl-aminomethyl)phenylguanidine (12) was chosen as lead compound for this purpose. This atomic positional scanning clearly revealed that the nitrogen as well as the carbonyl oxygen of the urethane group is involved in hydrogen-bonding interactions and that their substitution is accompanied by more or less strong reduction of inhibitory potency (16, 18, 19). However, substitution of the urethane moiety with the isosteric ureido group (17, WX-293T) improved the inhibition constant by a factor of 5 (Ki = 2.4 μM), which implicates the formation of an additional hydrogen bond, most probably involving the ureido NH as the new hydrogen donor group. The selectivity ratio of compound 17 vs. plasmin, fXa, and tPA is at least 400 vs. thrombin 250.

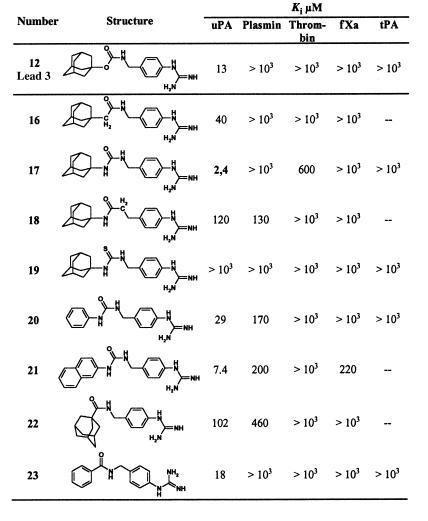

X-Ray Crystal Structure of the uPA/WX-293T Complex.

With the successful expression of βc-uPA and its crystallization as a complex with the low-affinity reversible inhibitor benzamidine (E. Zeslawska, A. Schweinitz, A. Karcher, P. Sondermann, R.H. & U.J., unpublished work), crystals became available for soaking experiments with the described (4-aminomethyl)phenylguanidine-based uPA inhibitors. These x-ray crystallographic analyses yielded a difference electron density map that allowed for the precise identification of all heavy atoms of N-(1-adamantyl)-N′-(4-guanidinobenzyl)urea (WX-293T) when bound to the active site of the enzyme. As discussed above, the inhibitor had intentionally been designed to occupy the arginine-specific S1 pocket and possibly the hydrophobic S3/S4 subsites of uPA in a similar manner as the substrate-like inhibitor H-Glu-Gly-Arg-CMK (25). Therefore, the binding mode found, as outlined in Scheme S1 and shown in the three-dimensional context (Fig. 1a), was most surprising. The phenylguanidine moiety of the inhibitor occupies the S1 pocket, whereas the planar and rigid ureido group crosses the active site and places the bulky hydrophobic adamantyl residue in the shallow S1′ subsite, in contrast to the substrate-like binding mode of irreversible inhibitor H-Glu-Gly-Arg-CMK (25). The overall fold of βc-uPA is identical to that reported previously (25).

Scheme 1.

Schematic representation of the binding mode of inhibitor 17 (WX-293T) to βc-uPA as derived from the x-ray crystal structure.

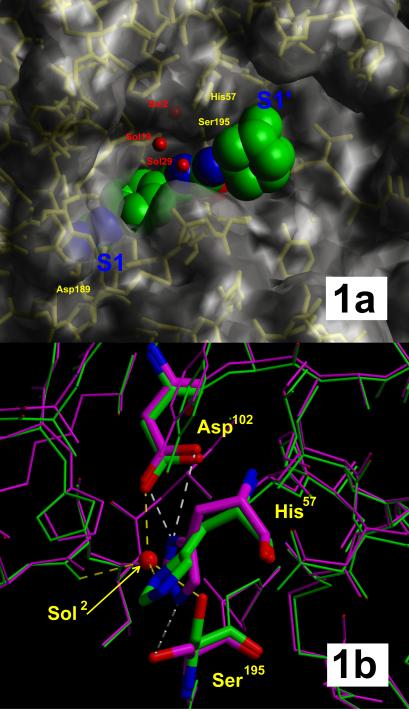

Figure 1.

(a) Semitransparent surface representation of the x-ray structure of the uPA/inhibitor 17 (WX-293T) complex. Red balls represent hydrogen-bound water molecules. The inhibitor is colored green (carbon), blue (nitrogen), and red (oxygen).The adamantyl residue of the inhibitor fits well into a hydrophobic S1′ box of uPA. (b) Comparison of the active site of βc-uPA when complexed with benzamidine (violet) and with the inhibitor (WX-293T) (green). The figure was prepared with molscript (45) and rendered with raster 3d (46).

The phenylguanidine moiety is inserted deeply into the S1 pocket (Fig. 1a), with its phenyl ring sandwiched between uPA segments Trp-215–Gly-216 and Ser-190–Gln-192, and with the guanidino group forming the expected canonical salt bridge to the Asp-189 carboxylate and making additional hydrogen bonds with the γ-OH of Ser-190 as well as with the carbonyl oxygen of Gly-219. Compared with benzamidine bound to βc-uPA (E. Zeslawska, A. Schweinitz, A. Karcher, P. Sondermann, R.H. & U.J., unpublished work) and to other trypsin-like proteases, the phenyl ring is considerably rotated along the molecular axis (Fig. 1a). The guanidino group of WX-293T extends deeper into the βc-uPA S1 pocket than the guanidino groups of bound Arg-P1 residues [as in H-Glu-Gly-Arg-CMK (25)] normally do, so that the most distal nitrogen (besides forming a charged hydrogen bond to one Asp-189 carboxylate oxygen) forms hydrogen bonds to the more internal water molecule Sol9, whereas the anilino nitrogen binds to Gly-219 O; furthermore, this guanidino group is significantly rotated of the phenyl plane allowing optimal hydrogen bond formation to the Ser-190 Oγ. The ureido group, placed by the methylene spacer close to the active site of βc-uPA, is involved in four defined (partially water-mediated) hydrogen bonds as illustrated in Scheme S1; the carbonyl oxygen binds into the oxyanion hole making hydrogen bonds to the backbone NH groups of Gly-193 and Ser-195, whereas the nitrogens are connected via water molecules each to the backbone carbonyl of Ser-214 and to the ordered side-chain carboxamide group of Gln-192, respectively. Via this rigid ureido lever, the hydrophobic adamantyl moiety is put into the shallow hydrophobic depression of the S1′ subsite, allowing it to nestle toward the Cys-58/Cys-42 disulfide bridge, the carbonyl sides of His-57 and Val-41, the backbone atoms of the Gly-193–Ser-195 strand, and against the flat (hydrophobic) side of the imidazole ring of His-57.

This His-57 side chain and the adjacent Ser-195 Oγ are considerably displaced compared with their positions in benzamidine-inhibited βc-uPA (E. Zeslawska, A. Schweinitz, A. Karcher, P. Sondermann, R.H. & U.J., unpublished work) or other serine proteases with “active” active-site conformation (Fig. 1b). According to about 120° and 90° rotations around κ1 and κ2, the imidazole group is turned to the “out” position [rarely observed in a few other serine proteases with active-site binding of nonpeptidic inhibitors (36)] stacking to the His-99 imidazole, whereas the Oγ atom of Ser-195 on a κ1 rotation from −70° to 180° has moved into a more internal protein cavity formed by Ala-55 Cβ, Val-213 O, and Cys-58 Sγ. The “normal” position of the His-57 imidazole moiety becomes occupied by a fixed water molecule (Sol2, Fig. 1b), which is almost ideally surrounded in a tetrahedral manner by His-57 Nδ1, Ser-195 Oγ, Asp-102 Oδ1 and Ser-214 O to make short hydrogen bonds. This rearrangement might be to avoid unfavorable contacts of Ser-195 with the first ureido nitrogen, simultaneously allowing short hydrogen bond formation with the enclosed water molecule Sol2. This water molecule in turn is built in the center of an apparently quite favorable hydrogen bond network. The His-57 imidazole, besides participating in this network, contacts the adamantyl group.

Toxicity Assay.

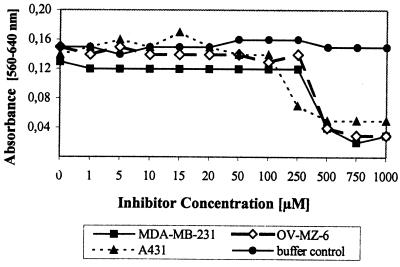

Fourty-eight hours after inhibitor application, cell viability was assessed by quantifying cell proliferation (Fig. 2). Cells cultured in the presence of control buffer remained viable, indicating that the vehicle did not exert toxic effects. Concentrations of WX-293T up to 250 μM did not appear to significantly alter cell viability of both OV-MZ-6 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines. Interestingly, in the case of the keratinocyte-derived cell line A431, lower concentrations affected cell proliferation. Unaltered cell survival at WX-293T concentrations at least 40-fold higher than the Ki value toward uPA indicates that this inhibitor is applicable in a wide concentration range.

Figure 2.

Effects of inhibitor 17 (WX-293T) on cell proliferation. Only the buffer control for OV-MZ-6 cells is depicted.

Discussion

Knowledge about the binding mode of the most active urea derivative N-(1-adamantyl)-N′-(4-guanidinobenzyl)urea (WX-293T) to uPA was expected to facilitate further improvements in potency and possibly even of related pharmacokinetic properties. Although important information about binding modes of inhibitors to trypsin-like enzymes was obtained repeatedly from x-ray crystal structures of trypsin/inhibitor complexes when related coordinates were used in analogy modeling of the target enzyme/inhibitor complexes (37–41), this approach could not be applied in the present case because of the lack of affinity of the uPA inhibitor for trypsin. Even modeling experiments using the coordinates of the known uPA x-ray structure (25) failed because of the relatively narrow S1 pocket. From the x-ray crystal structure of the uPA/WX-293T complex, a reasonable explanation can be drawn as the active site His and Ser residues are significantly displaced from their original positions to accommodate the inhibitor. The x-ray crystal structure also yields the rationale for the higher binding affinity of the urea compounds if compared with the urethanyl derivatives, e.g., Ki = 2.4 μM for 17 and Ki = 7.4 μM for 23, which derives from an additional hydrogen bond between the ureido group and the enzyme. Similarly, the simple amide derivatives 16 and 18 that lack this additional hydrogen bond are characterized by significantly enhanced Ki values. The lack of inhibitory activity of the thiourea derivative 19, which might be explained by the sterically more demanding sulfur atom, is surprising.

It is difficult to rationalize the very low affinity of most of the (4-aminomethyl)phenylguanidine derivatives for other trypsin-like proteases (Tables 1–3). In the case of thrombin, fXa, and tPA, this may derive from the absence of Ser-190, which is replaced by an Ala residue that is no longer able to saturate the full hydrogen bond capacity of the guanidino group. In thrombin (42) and fXa (43), the S1′ subsites are reduced in size by the side chains of Lys-60F and Gln-61, respectively, and in tPA (44) the charged side chains of Arg-39 and Glu-60A are placed close to S1′, in agreement with weaker binding. Furthermore, the His-57 imidazole would be strongly hindered to reach the “out” position in thrombin, and might have difficulties to do so in tPA and fXa. In addition, minor structural changes in uPA (such as the Ser-195 side chain rotation, or the flexibility of the S1 specificity pocket) may allow optimal adaptation of these relatively rigid inhibitors. Their synergistic action might contribute to the dramatic preference of WX-293T for uPA.

In terms of further structure-based design of uPA inhibitors, the most interesting result derived from this x-ray structure is the occupancy of the S1′ subsite by this new type of uPA inhibitors, which should allow further improvements in potency. Thereby precious assistance of x-ray crystallographic analysis can be expected by the facile displacement of the low-affinity benzamidine from these βc-uPA crystals.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mrs. Christa Böttner and Mr. Reiner Sieber for performing the enzyme assays and Ewa Zeslawska for preparing the uPA crystals. This work was supported by grants A1, A2, and A4 of the Sonderforschungsbereich 469 of the Ludwig-Maximilian University of Munich and the Graduiertenkolleg 333 of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

Abbreviations

- uPA

urokinase-type plasminogen activator

- tPA

tissue PA

- fXa

factor Xa

- Boc

tert-butyloxycarbonyl

- Z

benzyloxycarbonyl

- βc-uPA

B-chain of activated uPA

- uPAR

uPA receptor

Footnotes

Data deposition: The coordinates reported in this paper have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.rcsb.org (PDB ID code 1EJN).

References

- 1.Reuning U, Magdolen V, Wilhelm O, Fischer K, Lutz V, Graeff H, Schmitt M. Int J Oncol. 1998;13:893–906. doi: 10.3892/ijo.13.5.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmitt M, Harbeck N, Thomssen C, Wilhelm O, Magdolen V, Reuning U, Ulm K, Höfler H, Jänicke F, Graeff H. Thromb Haemost. 1997;78:285–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreasen P A, Kjøller L, Christensen L, Duffy M J. Int J Cancer. 1997;72:1–22. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970703)72:1<1::aid-ijc1>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeClerck Y A, Imren S, Montgomery A M, Mueller B M, Reisfeld R A, Laug W E. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;425:89–97. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5391-5_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramos-DeSimone N, Hahn-Dantona E, Sipley J, Nagase H, French D L, Quigley J P. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13066–13076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danø K, Behrendt M, Brünner N, Ellis V, Ploug M, Pyke C. Fibrinolysis. 1994;8:189–202. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duffy M J, O'Grady P, Devaney D, O'Siorain L, Fennelly J J, Lijnen H J. Cancer. 1988;62:531–533. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880801)62:3<531::aid-cncr2820620315>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Achbarou A, Kaiser S, Tremblay G, Sainte-Marie L G, Brodt P, Goltzman D, Rabbani S A. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2372–2377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fazioli F, Blasi F. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1994;15:25–29. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hauptmann J, Stürzebecher J. Thromb Res. 1999;93:203–241. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(98)00192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Obeidi F, Ostrem J A. Drug Discovery Today. 1998;3:223–231. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magdolen V, Arroyo de Prada N, Sperl S, Muehlenweg B, Luther T, Wilhelm O G, Magdolen U, Graeff H, Reuning U, Schmitt M. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2000;477:331–342. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46826-3_36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stürzebecher J, Markwardt F. Pharmazie. 1978;33:599–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tidwell R R, Geratz J D, Dubovi E J. J Med Chem. 1983;26:294–298. doi: 10.1021/jm00356a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vassalli J D, Belin D. FEBS Lett. 1987;214:187–191. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang H, Henkin J, Kim K H, Greer J. J Med Chem. 1990;33:2956–2961. doi: 10.1021/jm00173a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stürzebecher J, Vieweg H, Steinmetzer T, Schweinitz A, Stubbs M T, Renatus M, Wikström P. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1999;9:3147–3152. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00541-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Billström A, Hartley-Asp B, Lecander I, Batra S, Åstedt B. Int J Cancer. 1995;61:542–547. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910610419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jankun J, Keck R W, Skrzypczak-Jankun E, Swiercz R. Cancer Res. 1997;57:559–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Towle M J, Lee A, Maduakor E C, Schwartz C E, Bridges A J, Littlefield B A. Cancer Res. 1993;53:2553–2559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alonso D F, Farias E F, Ladeda V, Davel L, Puricelli L, Bal de Kier Joffé E. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996;40:209–223. doi: 10.1007/BF01806809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alonso D F, Tejera A M, Farias E F, Bal de Kier Joffé E, Gómez D E. Anticancer Res. 1998;18:4499–4504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rabbani S A, Harakidas P, Davidson D J, Henkin J, Mazar A P. Int J Cancer. 1995;63:840–845. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910630615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xing R H, Mazar A, Henkin J, Rabbani S A. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3585–3593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spraggon G, Phillips C, Nowak U K, Ponting C P, Saunders D, Dobson C M, Stuart D I, Jones E Y. Structure (London) 1995;3:681–691. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feichtinger K, Zapf C, Sings H L, Goodman M. J Org Chem. 1998;63:3804–3805. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu Y, Matsueda G R, Bernatowicz M. Synth Commun. 1993;23:3055–3060. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwyzer R, Sieber P, Zatsko K. Helv Chim Acta. 1958;41:491–498. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gabriel B, Stubbs M T, Bergner A, Hauptmann J, Bode W, Stürzebecher J, Moroder L. J Med Chem. 1998;41:4240–4250. doi: 10.1021/jm980227t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collaborative Computational Project Number 4. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50:760–763. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brunger A T, Adams P D, Clore G M, DeLano W L, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve R W, Jiang J S, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu N S, et al. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Engh R A, Huber R. Acta Crystallogr A. 1991;47:392–400. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones T A. J Appl Crystallogr. 1978;11:268–272. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Möbus V, Gerharz C D, Press U, Moll R, Beck T, Mellin W, Pollow K, Knapstein P G, Kreienberg R. Int J Cancer. 1992;52:76–84. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910520115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ke S H, Coombs G S, Tachias K, Corey D R, Madison E L. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20456–20462. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bode W, Wei A Z, Huber R, Meyer E, Travis J, Neumann S. EMBO J. 1986;5:2453–2458. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04521.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsuzaki T, Sasaki C, Okumura C, Umeyama H. J Biochem. 1989;105:949–952. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bode W, Turk D, Stürzebecher J. Eur J Biochem. 1990;193:175–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turk D, Stürzebecher J, Bode W. FEBS Lett. 1991;287:133–138. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80033-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Banner D W, Hadváry P. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:20085–20093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brandstetter H, Turk D, Hoeffken H W, Grosse D, Stürzebecher J, Martin P D, Edwards B F, Bode W. J Mol Biol. 1992;226:1085–1099. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)91054-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bode W, Mayr I, Baumann U, Huber R, Stone S R, Hofsteenge J. EMBO J. 1989;8:3467–3475. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Padmanabhan K, Padmanabhan K P, Tulinsky A, Park C H, Bode W, Huber R, Blankenship D T, Cardin A D, Kisiel W. J Mol Biol. 1993;232:947–966. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lamba D, Bauer M, Huber H, Fischer S, Rudolph R, Kohnert K, Bode W. J Mol Biol. 1996;258:117–135. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Merrit E A, Murphy M E P. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50:869–873. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994006396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kraulis P J. J Appl Crystallogr. 1991;24:946–950. [Google Scholar]