Abstract

With human neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor expressed in the Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, the Asp35Ala mutation, and especially the change of Pro34Asp35 to Ala34Ala35, decrease the compartmentalization and strongly accelerate internalization of the receptor. These changes are not associated with alterations in agonist affinity, G-protein interaction, dimerization, or level of expression of the mutated receptors relative to the wildtype receptor. The proline-flanked aspartate in the N-terminal extracellular segment of the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor thus apparently has a large role in anchoring and compartmentalization of the receptor. However, the Pro34Ala mutation does not significantly affect the embedding and cycling of the receptor.

Keywords: aspartate, compartmentalization, receptor cycling, receptor endocytosis, receptor masking

1. Introduction

The neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor stands out in the rhodopsin family of G-protein coupling receptors by twin features of slow cycling (Parker et al., 2001; Gicquiaux et al., 2002; Berglund et al., 2003b) and large surface compartmentalization (Parker et al., 2001; Parker et al., 2002a; Parker et al., 2007c), thus far not shown for any other member of this receptor group. There also is a tenacious attachment of agonists to the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor in particulates from fragmented cells (Dautzenberg and Neysari, 2005) and on the surface of intact cells (Parker et al., 2007a). In conjunction with the low endocytosis of the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor (Parker et al., 2001; Gicquiaux et al., 2002) this could enable an extended signaling per agonist binding event. The above features could also be linked to the known participation of this receptor in angiogenesis (Zukowska-Grojec et al., 1998; Ekstrand et al., 2003), and to the negative regulation of transmitter release (Tu et al., 2005) and feeding (Batterham et al., 2002) via the receptor.

Structural features responsible for the generally low cycling of the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor are currently not defined. However, the multiple anionic sidechains in the N-terminal extracellular domain, including those in the unique PDPEPE motif (residues 34–39 in the sequence of the human receptor (Rose et al., 1995)), could significantly contribute to immobilizing interactions with the extracellular matrix as well as with cell-linking receptors, including integrins and cadherins. N-terminal sequences rich in acidic residues are also present in a number of other peptide receptors known to support angiogenesis (Parker et al., 2005b).

To clarify the possible importance of this type of structure for properties of the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor, we mutated to alanine the Pro34 and Asp35 residues in the human receptor. These choices were based on the known importance of aspartate for interactions of integrins and other receptors with the extracellular matrix (e.g. Ma et al., 1995 and Kamata et al., 1995). Our results indicate that the N-terminal Asp35, especially in tandem with Pro34, does strongly restrict the dynamism of the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor in the Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell membranes.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Mutation and expression of the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor

Oligonucleotides were constructed using the PrimerX program on the Bioinformatics website, and synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Skokie, IL, USA). A34: fw 5′ CTAGAGGTGAACTGGTCGCTGACCCTGAGCCAGAG 3′ ; rv 5′ CTCTGGCTCAGGGTCAGCGACCAGTTCACCTCTAG 3′ A34A35: fw 5′ CTCCTAGAGGTGAACTGGTCGCTGCCCCTGAGCCAGAGCTTATAG 3′; rv 5′ CTATAAGCTCTGGCTCAGGGGCAGCGACCAGTTCACCTCTAGGAG 3′ A35: fw 5′ GAGGTGAACTGGTCCCTGCGCCTGAGCCAGAGCTTATAG 3′; rv 5′ CTATAAGCTCTGGCTCAGGCGCAGGGACCAGTTCACCTC 3′

The oligonucleotides were used to induce mutations in the human neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor wildtype cDNA packaged in the Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA) pc3.1+ vector. This cDNA was donated by the University of Missouri at Rolla (MO, USA). The mutations were done with Stratagene (La Jolla, CA, USA) QuickChange II mutagenesis kit, using the instructions supplied by the manufacturer. The successful mutations (as verified by sequencing performed by the Molecular Resources Center of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center at Memphis, TN, USA) were amplified and stably expressed in the Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) – K1 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Bethesda, MD, USA) at 400 µg/ml of geneticin. All peptides were from the American Peptide Co. (Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The radioactive tracers were supplied by PerkinElmer (Cambridge, MA, USA).

2.2 Cell culture

The cell culture was done essentially as described (Parker et al., 2005a). The K1 line of Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO-K1; American Type Culture Collection, Baltimore, MD, USA) stably expressing the cloned non-mutated or mutated human Y2 receptors were cultured at 400 µg/ml geneticin in D-MEM/F12 medium (Gibco, Long Island, NY, USA) containing 6% (v/v) of fetal calf serum.

2.3 The assay for internalization of the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor

This assay employed 25 – 200 pM of [125I]-labeled human peptide YY(3–36) or 100 pM porcine peptide YY(1–36), over 1 to 15 min at 37 °C. After washing with cold saline / Ca2+ / Mg2+ solution (140 mM NaCl + 3 mM CaCl2 + 1 mM MgCl2 + 10 mM NaHCO3) , the surface Y2 binding was quantitated by extraction with cold 0.2 M acetic acid – 0.5 M sodium chloride (7 min at 0–4 °C), and the tracer internalized with the receptor was measured in residues following this extraction. The unextracted labeled peptide was considered as internalized with the receptor (as documented in (Parker et al., 2002b), esp. Fig. 1; also see Fig. 3C in this study.).

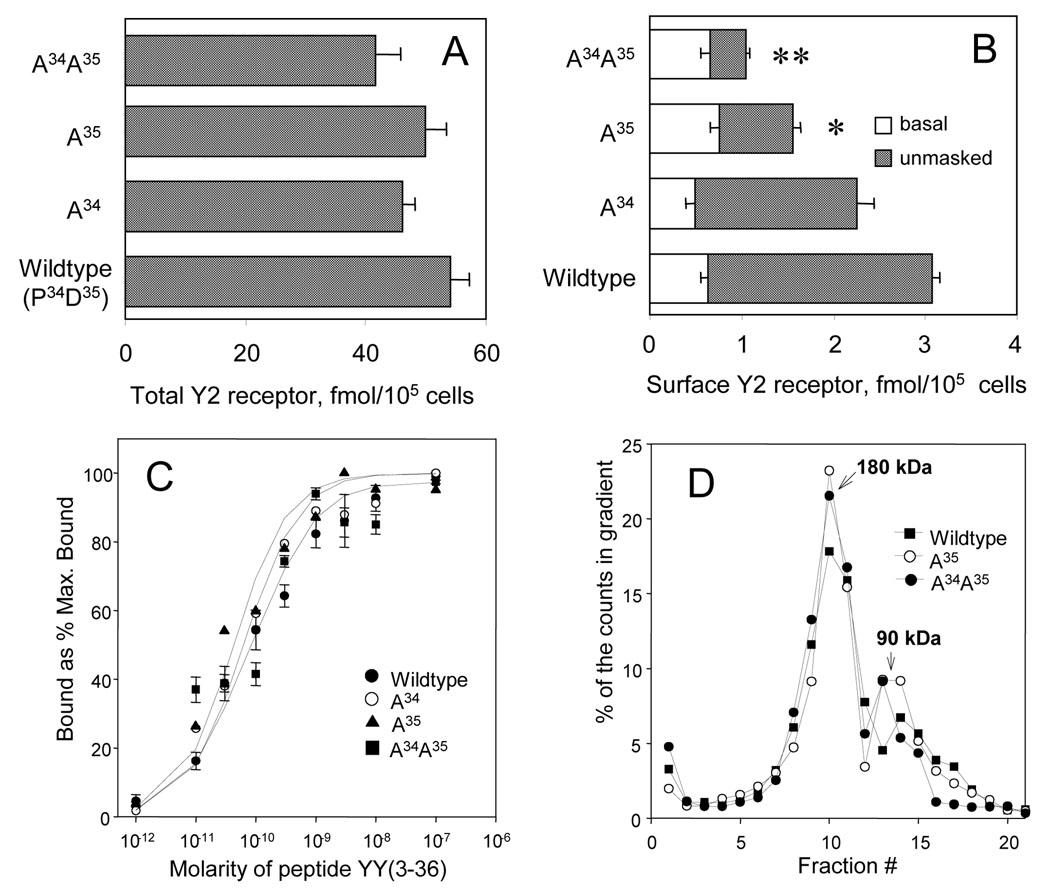

Fig. 1.

Levels of the CHO cell-expressed wildtype and N-terminally mutated human neuropeptide Y Y2 receptors, and a comparison of the activity of the Gi nucleotide site and the receptor binding site in particulates from these expressions. A. The overall binding of the agonist [125I] peptide YY(3–36) for the wildtype (WT) and the N-terminally mutated receptors bearing the indicated mutations. The measurements were done on particulates from the respective expressions and the corresponding binding parameters are shown in Table 1. B. The basal and phenylarsine oxide (PAO; 10 µM) - unmasked surface binding of [125I] peptide YY(3–36). The acid saline-extracted binding of 100 pM [125I] peptide YY(3–36) was measured after 12 min of labeling at 37 °C, without or with the arsenical in the medium. Significant differences in post hoc Tukey tests with the wildtype expression for the unmasked binding are indicated by asterisks (* for 95% confidence; ** for 99% confidence). C. Stimulation of the binding of [35S]GTPγS (200 pM) by peptide YY(3–36) at eight concentrations in the range of 10 pM to 100 nM (using the protocol detailed in Parker et al., 2005a). The results are averages of three separate binding experiments. The EC50 values, in pM peptide YY(3–36) ± 1 S.E.M. : wildtype, 43 ± 4.8; A34, 46 ± 5.5; A35 48 ± 8; A34A35, 55 ± 9. The ratios of fmol bound at 200 pM [35S]GTPγS and 100 pM [125I] peptide YY(3–36) for the same samples (n = 6): wildtype, 0.43 ± 0.04; A34, 0.49 ± 0.02; A35, 0.54 ± 0.03; A34A35, 0.61 ± 0.015. D. The binding of [125I] peptide YY(3–36) (20 pM, 30 min at 25 °C) to the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor monomer/Gi α complex (90 kDa) and to the receptor dimer / G-protein heterotrimer complex (180 kDa) separated in 5–20% sucrose gradients (18 h at 218,000 × gmax and 5 °C) after solubilization at 10 mM each of cholate and digitonin (using the protocol detailed in Parker et al., 2008). The profiles shown are representative of at least two runs. The proportion of dimers as estimated in the ImageJ program was above 60% in all cases.

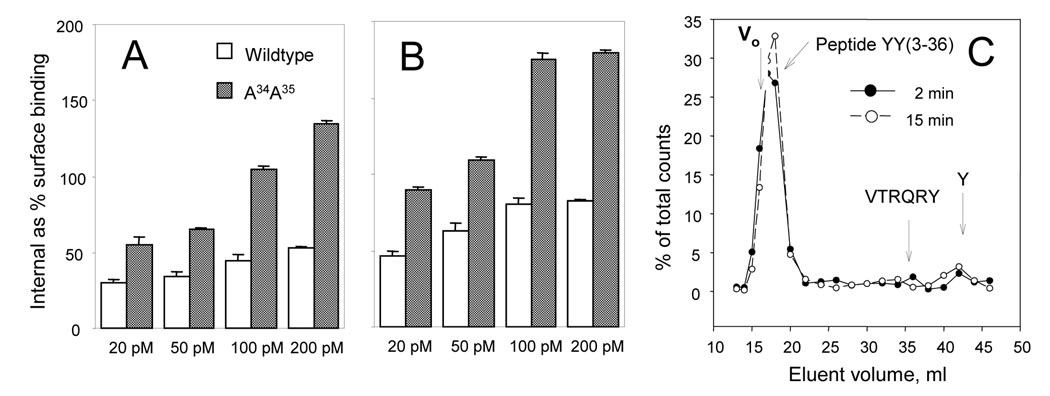

Fig. 3.

Binding of [125I] peptide YY(3–36) shows a consistently increased internalization of the Y2 agonist in cells expressing the A34A35 receptor in the range of 20 – 200 pM, and an equilibration of receptor intake and processing / degradation within short intervals. A. Receptor-linked internalization at 20, 50, 100 and 200 pM of the tracer over 4 min at 37 °C. B. Receptor-linked internalization at 20, 50, 100 and 200 pM of the tracer over 10 min at 37 °C. C. Bio-Gel P-4 gel filtration (using 35 ml columns in 1 M CH3COOH) shows about 80% of intact internalized agonist at 2 and at 15 min of internalization of [125I]PYY(3–36) (at 100 pM) with the A34A35 receptor. Very similar profiles were obtained with the wildtype receptor, and also with labeling periods of 4, 7 and 10 min. The elution positions at arrows: Vo, the void volume; VTRQRY, the C-terminal hexapeptide of peptide YY(3–36), Y, the C-terminal tyrosine of peptide YY(3–36), both detected by [125I] labeling and verified by HPLC. The total column volume is at the position of the free tyrosine.

2.4 The assay of compartmentalization of the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor

The unmasking of surface sites was effected by pre-treatment with the permeabilizing detergent digitonin at 10 µM for 15 min at 25 °C, followed by washing and labeling with [125I] peptide YY(3–36) over 4 or 10 min at 37 °C, or by labeling for 4 or 10 min at 37 °C in the presence of 10 µM phenylarsine oxide (added to the cells at 37 °C 5 min before the tracer). The labeling was terminated by dilution and washing with the cold saline solution, and extraction with 0.2 M CH3COOH / 0.5 M NaCl as above. Pertussis toxin at 1 ng / ml in the culture medium over 18 hours was used to deplete the compartmentalized surface Y2 sites (Parker et al., 2007b; Parker et al., 2007c).

2.5 The receptor and G-protein binding assays

To prepare particulates, the cells were homogenized in the receptor assay buffer (Parker et al., 2005a) using a Dounce homogenizer (8 strokes of the 0.1 mm-clearance pestle), the debris and nuclei were removed by sedimentation for 5 min at 600 gmax, and the supernatant sedimented for 12 min at 30,000 gmax to obtain pellets which were stored at −80 °C prior to use in assays. The affinity of the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor was assessed in particulates from the respective expressions by competition of 100 pM [125I] peptide YY(3–36) by unlabeled peptide YY(3–36) or peptide YY(1–36) in the range of 3 pM to 100 nM (Parker et al., 2005a). The activation of the Gi α subunit nucleotide site by the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor agonist PYY(3–36) was measured at 0.2 nM [35S]guanosine 5'-O-(3-thiotriphosphate) (GTPγS) using 0.01 – 100 nM peptide YY(3–36) (Parker et al., 2005a). The quantitation of the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor monomers and dimers, after labeling for 30 min at 25 °C with 20 pM [125I] peptide YY(3–36) and solubilization by 10 mM each of cholate and digitonin at 4 °C, was done by the sucrose gradient procedure detailed in (Parker et al., 2008).

2.6 Data analysis and statistics

The receptor binding parameters were estimated in the LIGAND program (Munson and Rodbard, 1980). The half-periods and maxima of saturation in internalization studies were estimated by non-linear hyperbolic fitting in the SigmaPlot software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, version 8.02). The proportion of dimers in the gradient profiles was estimated using the ImageJ program, available at the website of the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

3. Results

3.1 Levels, affinity, G-protein activity and oligomerization of the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor following N-terminal mutations

The mutations to A34, A35 and A34A35 did not strongly affect the overall expression of the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor relative to the wildtype. Thus, using cDNA and lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) inputs of 1 µg/ml and 1.5 µl/ml, respectively, and 30 ml of F12/D-MEM medium per 75 cm2 layer of confluent CHO cells, the total level of the receptors at the geneticin passage 8 was in the Bmax range of 60–75 fmol/mg protein (Table 1), or 40–50 fmol/100,000 cells (Fig. 1A), compared to about 80 fmol/mg protein or 55 fmol/100,000 cells for the wildtype receptor at the same passage (Table 1 and Fig. 1A). The surface receptor unmasked by phenylarsine oxide was close to the wildtype level for the A34 mutation, significantly lower than in the wildtype expression for the A35 mutation, and strongly reduced for the A34A35 mutation (Fig. 1B; also see Fig. 2C). The basal receptor levels, however, did not differ significantly (Fig. 1B; see also Fig. 2C).

Table 1.

The binding of two agonist peptides to wildtype and mutated neuropeptide Y Y2 receptors

| Agonist and receptor expression | Kdiss, pM | Bmax, fmol/mg protein |

|---|---|---|

| [125I] peptide YY(3–36) | ||

| Wildtype (P34D35) | 85.1 ±12 | 81.2 ± 4.4 |

| A34 | 83.5 ± 13.3 | 69.2 ± 3 |

| A35 | 82.5 ± 12.4 | 75.1 ±5 |

| A34A35 | 78.9 ± 11.9 | 62.6 ± 5.8 |

| [125I] peptide YY(1–36) | ||

| Wildtype | 80.3 ± 11.5 | 84.8 ± 8.8 |

| A34A35 | 73.4 ± 11.6 | 67.6 ± 4.5 |

Competition of either [125I]-labeled agonist (input at 100 pM) was done by eight concentrations of the corresponding unlabeled peptide in the range of 3 pM to 10 nM, and the non-specific binding was defined at 100 nM of the respective non-labeled peptide. The results are averages of at least three determinations for each agonist and paradigm.

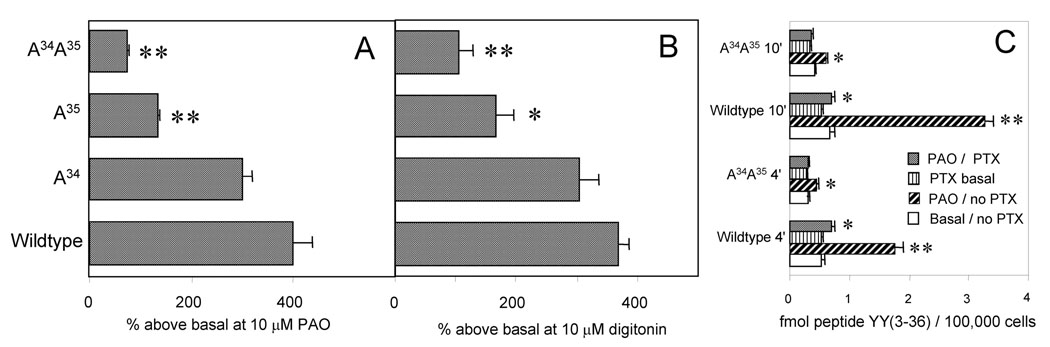

Fig. 2.

Compartmentalization of the cell surface binding sites is strongly decreased in the A35 and especially in the A34A35 mutation. [125I] peptide YY(3–36) (100 pM) was used to label the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor sites on the surface of cells in wells. All results are averages of at least six wells, ± 1 S.E.M. Differences in post hoc Tukey tests significant vs. the wildtype expression (A, B) or vs. the corresponding basal binding (C ) are indicated by asterisks (* for 95%, ** for 99% confidence). A. Unmasking by phenylarsine oxide (PAO; pretreatment for 5 min and co-treatment during the labeling with [125I] peptide YY(3–36) in wells for 10 min at 37 °C). B. Unmasking by pretreatment with 10 µM digitonin (15 min at 25 °C) followed by labeling of cells with [125I] peptide YY(3–36) in wells for 10 min at 37 °C. C. The basal and PAO-unmasked cell surface binding of [125I] peptide YY(3–36) to cells pretreated with pertussis toxin (PTX) for 18 h in the culture medium. The labeling was for 4 or 10 min at 37 °C, and PAO (10 µM) was added 5 min before the tracer.

With particulates isolated from homogenates of CHO cells expressing the wildtype and mutated neuropeptide Y Y2 receptors, affinities for the Y2 subtype-selective agonist peptide YY(3–36) and for the non-selective Y receptor agonist peptide YY(1–36) were quite similar (Table 1). The G-protein coupling ability, as evaluated by stimulation with 100 nM peptide YY(3–36) of the binding of [35S]GTPγS to particulates, did not show significant affinity differences (Fig. 1C). The ratios of the binding at 200 pM [35S]GTPγS and at 100 pM [[125I] peptide YY(3–36) were for any expression within 20% of the common average (the legend of Fig. 1C). The labeling of receptor monomers and dimers was also similar for the wildtype and the mutated receptors. More than 60% of the receptor-bound agonist was associated with the ~180 kDa complex of the Y2 dimer with heterotrimeric G-proteins (Parker et al., 2007c) (Fig. 1D).

3.2 Compartmentalization of the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor following N-terminal mutations

A general consideration of the compartmentalization of the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor in a cell line and in rat brain is presented in two recent communications (Parker et al., 2007c; Parker and Balasubramaniam, 2008). Unmasking by 10 µM phenylarsine oxide increased the agonist-accessible surface receptor to a large and similar degree for the wildtype receptor and the A34 mutation (Fig. 2A). However, relative to the basal level, the unmasked receptor was significantly less for the A35 mutation, and very much lower with the change to A34A35 (Fig. 2A). A similar decrease in compartmentalization of the receptor for the A34A35 and the A35 mutation was found by unmasking with the detergent digitonin at 10 µM (Fig. 2B). It should be emphasized that the pretreatment with this concentration of digitonin at 25 °C did not result in a loss of cell protein or a detachment of cells. Pretreatment with pertussis toxin at 1 ng/ml for 18 h did not substantially reduce the basal cell surface binding of the agonist [125I] peptide YY(3–36) in either the wildtype or the A34A35 expression. However, the surface sites that could be unmasked by the arsenical, as expected, were strongly reduced by the toxin in the wildtype (Parker et al., 2007b), and almost eliminated in the mutant expression, as observed at either 4 min or 10 min of labeling with the agonist (Fig. 2C).

3.3 Internalization of the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor following N-terminal mutations

Effects of mutations on the rate of internalization of the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor were first examined with the A34A35 mutant using four concentrations of [125I] peptide YY(3–36) in the range producing a substantial saturation (as based on the Kdiss values in Table 1) of the binding of this agonist (Fig. 3A, B). The internalization was found to be accelerated significantly in the mutant over the entire input range of the labeled agonist, at either 4 or 10 min of labeling. The increase relative to the wildtype was similar at 4 min (Fig. 3A) and 10 min (Fig. 3B) of labeling. As shown in Fig. 3C, at an input of 100 pM the recovered internalized peptide is intact at a constant ~80% between 2 and 15 min of incorporation. The intact agonist is tenaciously bound and should be largely associated with the receptor (Dautzenberg and Neysari, 2005; Parker et al., 2007c). We found no accumulation of either the principal product of peptide YY processing, the C-terminal hexapeptide VTRQRY (Frerker et al., 2007), or of the C-terminal tyrosine, both of which would be detected by the [125I] label (which in peptide YY(3–36) labeled via the chloramine-T procedure is localized by more than 85% in the C-terminal tyrosine).

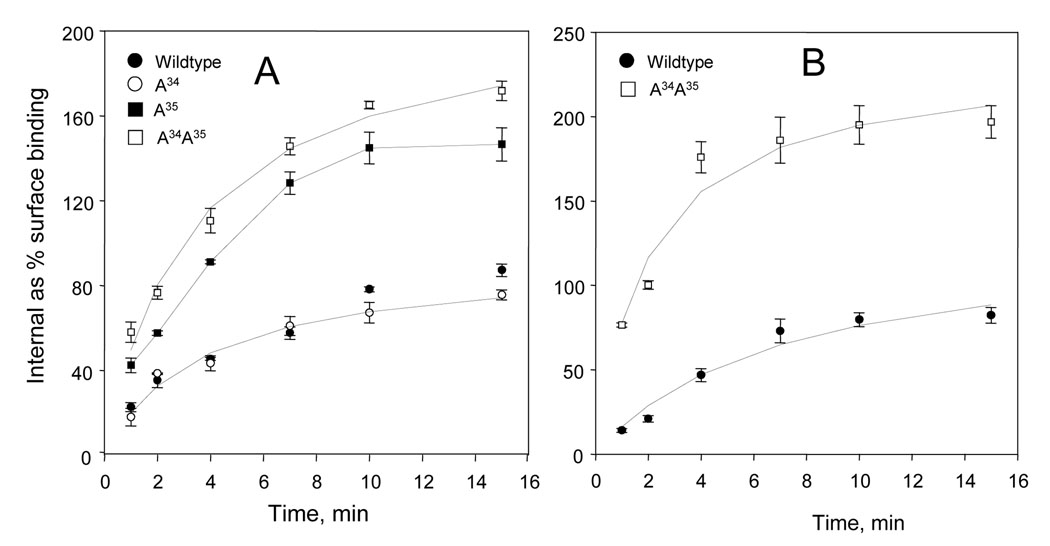

The agonist internalization, as measured by the uptake of 100 pM [125I] peptide YY(3–36), was much increased by the A34A35 mutation, and also strongly increased by the A35 mutation (Fig. 4A). The A34 mutation, however, showed a low degree of internalization, similar to the wildtype receptor (Fig. 4A and Table 2). Internalization was also compared using as the tracer the non-selective Y receptor agonist [125I] peptide YY(1–36) (the parent peptide of peptide YY(3–36) ), which at the Y2 sites has binding properties very similar to peptide YY(3–36) (Table 1). The full-length peptide YY internalized somewhat faster than peptide YY(3–36) in the wildtype expression, and especially in the A34A35 expression (Fig. 4B and Table 2). The difference in internalization between the A34A35 mutation and the wildtype expression was especially pronounced at lower temperatures, being about fourfold between 4–30 min at 15 °C.

Fig. 4.

Kinetics of internalization of the wildtype, A34, A35 and A34A35 neuropeptide Y Y2 receptors in CHO cells followed by two labeled agonists. The results are averages of 6–8 wells. A. The kinetics of internalization at 100 pM [125I] peptide YY(3–36), the selective agonist of the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor. The binding parameters are reported in Table 2. The difference between the wildtype and the A34A35 mutation was significant in the Student’s t test. B. The kinetics of internalization at 100 pM [125I peptide YY(1–36), a non-selective agonist of the neuropeptide Y Y1, Y2 and Y5 receptors. The binding parameters are reported in Table 2. The difference between the wildtype and the A34A35 mutation was significant in Student’s t test.

Table 2.

Internalization of [125I] peptide YY(3–36) and [125I] peptide YY(1–36) with neuropeptide Y Y2 receptors

| Agonist and expression | Half-period, min. ± S.E. | Max. internal tracer as % surface binding |

|---|---|---|

| [125I] peptide YY(3–36) | ||

| Wildtype (P34D35) | 5.55 ± 1.57 | 117 ± 14 |

| A34 | 3.67 ± 0.77 | 93 ± 7 |

| A35 | 4.21 ± 0.78 | 196 ± 14 b |

| A34A35 | 3.28 ± 0.46 a | 212 ± 10 b |

| [125I] peptide YY(1–36) | ||

| Wildtype (P34D35) | 3.82± 0.14 | 130 ± 21 |

| A34A35 | 2.02 ± 0.51 a | 234 ± 26 b |

The results are averages of six measurements using 100 pM of [125I]-labeled agonists and time points of 2, 4, 7, 10 and 15 min. The corresponding data are shown in graphs A (for peptide YY(3–36) ) and B (for peptide YY(1–36) ) of Fig. 5. The half-periods (min) and maximum internalized binding as percentage of the corresponding surface binding were estimated in nonlinear hyperbolic fits. Significance in Student’s t tests of parameters against the corresponding wildtype average:

at 95%

at 99% confidence. With the wildtype expression, the internalization of [125I] peptide YY(3–36) increased almost four-fold over the input range of 20–100 pM at time points of 4 and 10 min (n = 8), and with a good saturation between 100 and 200 pM (see Fig. 3).

We also tested the anionic polysaccharide heparin as a possible promoter of internalization of the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor. At 5 µM, heparin (6.5 kDa) indeed increased the internalization of 100 pM [125I] peptide YY(3–36) significantly at either 4 min or 10 min in the A34A35 expression (by 43.5 ± 3.5 and 25.1 ± 5%, respectively), but only marginally in the wildtype expression (19.4 ± 2 and 4.8 ± 1.8%, respectively; n = 12 for both). At up to 30 µM, heparin did not affect the affinity and capacity of the binding of peptide YY(3–36) to either the cell surface or the particulate neuropeptide Y Y2 receptors.

4. Discussion

The internalization of agonists of the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor is prevented by common inhibitors of clathrin-linked endocytosis (Parker et al., 2001; Parker et al., 2002a), and thus should be coupled with endocytosis of the receptor. One should note that the estimated rate of internalization of the human neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor in CHO cells at 100 pM of the agonist peptide YY(3–36) (wildtype half-period of ~ 6 min) is much higher than the rate we previously found for the guinea-pig neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor at 50 pM of the same agonist (half-period ~15 min; (Parker et al., 2001). This difference is connected primarily to the twice larger concentration of the labeled agonist used in the current study, since the internalization of unmodified Y receptors is substantially accelerated by increasing concentration of the agonists (Parker et al., 2005a). We found a sustained increase in the rate of internalization of the receptor-linked agonist with concentrations up to 200 pM.

Our current estimates differ even more from the value obtained with the Renilla luciferase tagged rhesus neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor in the human embryonic kidney-293 (HEK-293) cells (t1/2 ~23 min; (Berglund et al., 2003b). It should be noted that the studies of internalization of tagged Y receptors in HEK-293 cells used very high concentrations of the driving agonists (100 nM (Gicquiaux et al., 2002) or 1 µM (Berglund et al., 2003b)), possibly pointing to low rates of cycling of the constructs. Also, the above studies with fluorescently tagged Y receptors used suspensions of HEK-293 cells, and our work with unmodified receptors employed CHO cell monolayers. The receptor-linked internalization of agonist peptides by monolayer cultures could be substantially faster than in suspensions of the same cells (e.g. Blanchard et al., 1983). The apparent differences could be evaluated by comparing simultaneously the kinetics of internalization of the fluorescent neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor constructs and of the [125I]-labeled agonists.

The fraction of the cycled neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor is small compared to other neuropeptide Y receptors, in accord with previous observations (Parker et al., 2001; Gicquiaux et al., 2002; Berglund et al., 2003a). This again points to an immobilization through compartmentalization of a large part of the surface neuropeptide Y Y2 receptors. However, most importantly, the internalization of both labeled agonists is very much faster and larger with the A34A35 mutation, indicating a significant reduction in the rate of internalization by the native P34D35 motif.

We utilized internalization of the agonist peptides to assess the surface dynamics of the wildtype and the mutated neuropeptide Y Y2 receptors. The approach based on cDNA constructs containing receptors and fluorescent molecules (for an in-depth review see Bohme et al., 2007) was not used, since the covalent additions, especially of long sequences, could significantly influence the cycling of the G-protein coupling receptors, as already noted for human β-adrenergic receptors (McLean and Milligan, 2000), and as seems likely from the available studies with the Y receptors (Gicquiaux et al., 2002; Berglund et al., 2003a). Also, with a protein examined for effects of point mutations, as in the present study, an additional large mutation (such as attachment of the 314-residue Renilla reniformis luciferase (The U.S. National Library of Medicine access CAA01908), or the 228-residue Aequorea victoria green fluorescent peptide (Swiss-Protein access P42212) to the 381-residue human neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor protein (Rose et al., 1995) may have differential effects on the receptor properties that can be disproportionately affected by the mutations under scrutiny. In the case of the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor, co-internalization of the agonist with the receptor is not significantly compromised by dissociation of the agonist, since the intact Y2 agonist is quasi-irreversibly associated with the receptor (Dautzenberg and Neysari, 2005; Parker et al., 2007c), and our results show no accumulation of the degraded agonist over the studied length of endocytosis. As is clear from our experiments, a large fraction of the internalized neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor agonist, essentially constant over short intervals, should represent receptor-agonist complexes.

We selected for this initial study the PD aspect of the PDPEPE sequence in the N-terminal extracellular segment of the human Y2 receptor, based on the known importance of aspartate sidechains in the association of integrins and other connector proteins with the extracellular matrix (Ma et al., 1995; Golbik et al., 2000). Among G-protein coupling receptors of all known families, this N-terminal extracellular sequence is found only in rodent and primate neuropeptide Y Y2 receptors. While thus far there are no specific reports on the use of a PD motif in specific interactions with juxtacellular or extracellular partners, it is noteworthy that multiple sequences rich in PD and PE motifs are found in the large extracellular domains of the secretin group adhesion receptors ontogenetically associated with neuronal streams (McMillan et al., 2002). The bovine and porcine neuropeptide Y Y2 receptors have a modified, and also unique, PDSEPE motif, in which the hydroxyl sidechain sandwiched between Asp and Glu could serve in association with intercellular adhesion molecules and collagens, as in the case of integrin β2 (Kamata et al., 1995). Flexibility due to the flanking proline residues should enable multiple electrostatic interactions of the acidic residues with ionic partners, to a considerable binding strength (e.g. Jackson et al., 2006), and these interactions would involve spatially non-contiguous partners. There are no G-protein coupling receptors with PDPD sequence in the N-terminal extracellular domain, and the N-terminal extracellular PEPE sequence is, beside the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptors, found only in the orphan GPCR12. Single acidic residues flanked by proline in this domain are more frequent, with the PDP motif found in 11, and the PEP motif in 21 receptors in addition to the Y2 receptor. The above, however, adds to only about 40 molecules among the ~800 GPCRs with confirmed sequences, and could point to association of the carrier receptors with specific types of adhesion partners. The receptor internalization can be controlled by specific proteins of the extracellular matrix (e.g. (Boura-Halfon et al., 2003) for the insulin receptor), via multiple electrostatic interactions (Kauf et al., 2001). The stimulation of the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor internalization by heparin that we observed in the A34A35 mutant should relate to inhibition of contacts of the residues 36–39 (PEPE), possibly weakened due to the absence of residues P34 and D35. The neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor partners affected by heparin could include fibronectins in the extracellular matrix (Naito et al., 2000).

The strongly acidic N-termini found in a number of G-protein coupling receptors are frequently used as primary or auxiliary agonist-binding sites, e.g. in chemokine receptors (Blanpain et al., 1999; Proudfoot et al., 2001) and in the apelin receptor (Zhou et al., 2003). These domains can also have a role in the promotion of angiogenesis by the receptors (see e.g. Parker et al., 2005b). With the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor, the N-terminal domain is not involved in the ligand association (as is obvious from our finding the absence of sensitivity to heparin in the binding of a receptor agonist). The acidic / aromatic residue-rich N-terminal extracellular domain of the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor can therefore serve principally in anchoring and embedding interactions, and the PDPEPE motif appears to be importantly involved in these activities. This can also involve intermolecular bridges to metal ion-dependent adhesion sites of integrins (Rieu et al., 1996). Further studies should deal with effects upon the receptor cycling of modifications of other parts of the PDPEPE motif and of overlapping or adjacent sequences, as well as mutation to neutral residues of the entire motif, or deletion of the motif.

It is noteworthy that tissues rich in tubular epithelia, e.g. the kidney cortex, can contain the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor in excess of 1 pmol/mg membrane protein (Sheikh et al., 1989). Interactions of the receptor via the N-terminal extracellular domain with the extracellular matrix, or with other cells, could conceivably induce a transition of the receptor to the status of a structural constituent, even preventing detection by the conventional labeling techniques. Participation of the neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor in angiogenesis (Zukowska-Grojec et al., 1998; Ekstrand et al., 2003), tubulogenesis, and generally in the cell-cell and the cell-matrix (Kuo et al., 2007) association may need to be further addressed especially by cytochemical and immunochemical methods.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by The National Institutes of Health grants HD13703 and GM47122.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Batterham RL, Cowley MA, Small CJ, Herzog H, Cohen MA, Dakin CL, Wren AM, Brynes AE, Low MJ, Ghatei MA, Cone RD, Bloom SR. Gut hormone PYY(3–36) physiologically inhibits food intake. Nature. 2002;418:650–654. doi: 10.1038/nature00887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglund MM, Schober DA, Esterman MA, Gehlert DR. Neuropeptide Y Y4 receptor homodimers dissociate upon agonist stimulation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003a;307:1120–1126. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.055673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglund MM, Schober DA, Statnick MA, McDonald PH, Gehlert DR. The use of bioluminescence resonance energy transfer 2 to study neuropeptide Y receptor agonist-induced beta-arrestin 2 interaction. J Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003b;306:147–156. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.051227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard SG, Chang KJ, Cuatrecasas P. Characterization of the association of tritiated enkephalin with neuroblastoma cells under conditions optimal for receptor down regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258:1092–1097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanpain C, Doranz BJ, Vakili J, Rucker J, Govaerts C, Baik SS, Lorthioir O, Migeotte I, Libert F, Baleux F, Vassart G, Doms RW, Parmentier M. Multiple charged and aromatic residues in CCR5 amino-terminal domain are involved in high affinity binding of both chemokines and HIV-1 Env protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:34719–34727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohme I, Morl K, Bamming D, Meyer C, Beck-Sickinger AG. Tracking of human Y receptors in living cells-A fluorescence approach. Peptides. 2007;28:226–234. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boura-Halfon S, Voliovitch H, Feinstein R, Paz K, Zick Y. Extracellular matrix proteins modulate endocytosis of the insulin receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:16397–16404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212385200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dautzenberg FM, Neysari S. Irreversible binding kinetics of neuropeptide Y ligands to Y2 but not to Y1 and Y5 receptors. Pharmacology. 2005;75:21–29. doi: 10.1159/000085897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrand AJ, Cao R, Bjorndahl M, Nystrom S, Jonsson-Rylander AC, Hassani H, Hallberg B, Nordlander M, Cao Y. Deletion of neuropeptide Y (NPY) 2 receptor in mice results in blockage of NPY-induced angiogenesis and delayed wound healing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2003;100:6033–6038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1135965100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frerker N, Wagner L, Wolf R, Heiser U, Hoffmann T, Rahfeld JU, Schade J, Karl T, Naim HY, Alfalah M, Demuth HU, von Horsten S. Neuropeptide Y (NPY) cleaving enzymes: structural and functional homologues of dipeptidyl peptidase 4. Peptides. 2007;28:257–268. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gicquiaux H, Lecat S, Gaire M, Dieterlen A, Mely Y, Takeda K, Bucher B, Galzi JL. Rapid internalization and recycling of the human neuropeptide Y Y(1) receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:6645–6655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107224200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golbik R, Eble JA, Ries A, Kuhn K. The spatial orientation of the essential amino acid residues arginine and aspartate within the alpha1beta1 integrin recognition site of collagen IV has been resolved using fluorescence resonance energy transfer. J Mol Biol. 2000;297:501–509. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SN, Wang HY, Yergey A, Woods AS. Phosphate stabilization of intermolecular interactions. J. Proteome Res. 2006;5:122–126. doi: 10.1021/pr0503578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamata T, Wright R, Takada Y. Critical threonine and aspartic acid residues within the I domains of beta 2 integrins for interactions with intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) and C3bi. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:12531–12535. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauf AC, Hough SM, Bowditch RD. Recognition of fibronectin by the platelet integrin alpha IIb beta 3 involves an extended interface with multiple electrostatic interactions. Biochemistry. 2001;40:9159–9166. doi: 10.1021/bi010503x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo LE, Kitlinska JB, Tilan JU, Li L, Baker SB, Johnson MD, Lee EW, Burnett MS, Fricke ST, Kvetnansky R, Herzog H, Zukowska Z. Neuropeptide Y acts directly in the periphery on fat tissue and mediates stress-induced obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nature Medicine. 2007;13:803–811. doi: 10.1038/nm1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Conrad PJ, Webb DL, Blue ML. Aspartate 698 within a novel cation binding motif in alpha 4 integrin is required for cell adhesion. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:18401–18407. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.31.18401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean AJ, Milligan G. Ligand regulation of green fluorescent protein-tagged forms of the human beta(1)- and beta(2)-adrenoceptors; comparisons with the unmodified receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;130:1825–1832. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan DR, Kayes-Wandover KM, Richardson JA, White PC. Very large G protein-coupled receptor-1, the largest known cell surface protein, is highly expressed in the developing central nervous system. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:785–792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108929200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munson PJ, Rodbard D. LIGAND: a versatile computerized approach for characterization of ligand-binding proteins. Anal. Biochem. 1980;107:220–239. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90515-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito M, Fukuda T, Sekiguchi K, Yamada T. The domains of human fibronectin mediating the binding of alpha antigen, the most immunopotent antigen of mycobacteria that induces protective immunity against mycobacterial infection. Biochem. J. 2000;347(Pt 3):725–731. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MS, Sah R, Sheriff S, Balasubramaniam A, Parker SL. Internalization of cloned pancreatic polypeptide receptors is accelerated by all types of Y4 agonists. Regulatory Peptides. 2005a;132:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SL, Balasubramaniam A. Neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor in health and disease. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008;153:420–431. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SL, Kane JK, Parker MS, Berglund MM, Lundell IA, Li MD. Cloned neuropeptide Y (NPY) Y1 and pancreatic polypeptide Y4 receptors expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells show considerable agonist-driven internalization, in contrast to the NPY Y2 receptor. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001;268:877–886. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.01966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SL, Parker MS, Kane JK, Berglund MM. A pool of Y2 neuropeptide Y receptors activated by modifiers of membrane sulfhydryl or cholesterol balance. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002a;269:2315–2322. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SL, Parker MS, Lundell I, Balasubramaniam A, Buschauer A, Kane JK, Yalcin A, Berglund MM. Agonist internalization by cloned Y1 neuropeptide Y (NPY) receptor in Chinese hamster ovary cells shows strong preference for NPY, endosome- linked entry and fast receptor recycling. Regul. Pept. 2002b;107:49–62. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(02)00094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SL, Parker MS, Sah R, Balasubramaniam A, Sallee FR. Self-regulation of agonist activity at the Y receptors. Peptides. 2007a;28:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SL, Parker MS, Sah R, Balasubramaniam A, Sallee FR. Pertussis toxin induces parallel loss of neuropeptide Y Y(1) receptor dimers and G(i) alpha subunit function in CHO cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008;579:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SL, Parker MS, Sah R, Sallee F. Angiogenesis and rhodopsin-like receptors: A role for N-terminal acidic residues? Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005b;335:983–992. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SL, Parker MS, Sah R, Sallee FR, Balasubramaniam A. Parallel inactivation of Y2 receptor and G-proteins in CHO cells by pertussis toxin. Regul. Pept. 2007b;139:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SL, Parker MS, Sallee FR, Balasubramaniam A. Oligomerization of neuropeptide Y (NPY) Y2 receptors in CHO cells depends on functional pertussis toxin-sensitive G-proteins. Regul. Pept. 2007c;144:72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudfoot AE, Fritchley S, Borlat F, Shaw JP, Vilbois F, Zwahlen C, Trkola A, Marchant D, Clapham PR, Wells TN. The BBXB motif of RANTES is the principal site for heparin binding and controls receptor selectivity. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:10620–10626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010867200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieu P, Sugimori T, Griffith DL, Arnaout MA. Solvent-accessible residues on the metal ion-dependent adhesion site face of integrin CR3 mediate its binding to the neutrophil inhibitory factor. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:15858–15861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.27.15858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose PM, Fernandes P, Lynch JS, Frazier ST, Fisher SM, Kodukula K, Kienzle B, Seethala R. Cloning and functional expression of a cDNA encoding a human type 2 neuropeptide Y receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:22661–22664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.39.22661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh SP, Sheikh MI, Schwartz TW. Y2-type receptors for peptide YY on renal proximal tubular cells in the rabbit. Am. J. Physiol. 1989;257:F978–F984. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.257.6.F978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu B, Timofeeva O, Jiao Y, Nadler JV. Spontaneous release of neuropeptide Y tonically inhibits recurrent mossy fiber synaptic transmission in epileptic brain. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:1718–1729. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4835-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou N, Zhang X, Fan X, Argyris E, Fang J, Acheampong E, DuBois GC, Pomerantz RJ. The N-terminal domain of APJ, a CNS-based coreceptor for HIV-1, is essential for its receptor function and coreceptor activity. Virology. 2003;317:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zukowska-Grojec Z, Karwatowska-Prokopczuk E, Fisher TA, Ji H. Mechanisms of vascular growth-promoting effects of neuropeptide Y: role of its inducible receptors. Regul. Pept. 1998;75–76:231–238. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(98)00073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]