Abstract

This study discovered that glycyrrhetinic acid inhibited the human 20S proteasome at 22.3 µM. Esterification of the C-3 hydroxyl group on glycyrrhetinic acid with various carboxylic acid reagents yielded a series of analogs with marked improved potency. Among the derivatives, glycyrrhetinic acid 3-O-isophthalate (17) was the most potent compound with IC50 of 0.22 µM, which was approximately 100-fold more potent than glycyrrhetinic acid.

Keywords: Glycyrrhetinic acid, proteasome inhibitor, triterpene

Introduction

18β-glycyrrhetinic acid (GLA) is the aglycone of glycyrrhizic acid, a major component found in licorice root that has been widely used in traditional medicines, especially in Asia (1). The known pharmacological activities of GLA and glycyrrhizic acid include anti-inflammation, anti-ulcer, anti-allergenic, and anti-viral. The GLA derivative, carbenoxolone, has been used in Europe as a licensed medicine for the treatment of esophageal ulceration and inflammation (2). GLA was shown to have multiple biological activities, including inhibition of 11-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase and induction of mitochondrial permeability transition (3–5). How these biological activities contribute to the pharmacological effect of GLA remains to be determined.

The proteasome-ubiquitin pathway is known for breaking down proteins to remove the misfolded or damaged proteins in eukaryotic cells (6, 7). In the past decade, increasing evidence has indicated that the proteasome-ubiquitin system plays an important role in many cellular functions such as cell stress response, cell cycle regulation, cellular differentiation, and antigenic peptide generation. Therefore, targeting the proteasome-ubiquitin pathway has been considered a novel strategy for the treatment of various disorders such as neurodegenerative diseases, cancers, and inflammatory diseases (8).

The core structure of the proteasome is a barrel-shaped 20S complex that has four stacked rings each with 7 subunits (8). The two outer rings and two inner rings are named α rings and β rings, respectively. The 20S proteasome is activated when the regulatory protein complex PA700 or PA28 binds to the α ring that opens the channel in the 20S proteasome and allows the ubiquitin-tagged proteins to access the proteolytic sites located inside the chamber. Within the β rings, there are multiple proteolytic sites including two chymotrypsin-like (ChT-L), two trypsin-like (T-L), and two caspase-like (CA-L) proteolytic sites (10). The proteasome inhibitor PS341 (bortezomib) was successfully developed into an anti-cancer drug for the treatment of multiple myeloma (11). Differential inhibition of the three catalytic activities by bortezomib is believed to be critical for clinical benefit in disease treatment (12). Recently, we reported that betulinic acid (BA) and its derivatives could regulate the proteasome activities (13). BA acted as an activator of the 20S proteasome complex. On the other hand, some of the BA derivatives were shown to be inhibitors of the 20S proteasome.

Results and discussion

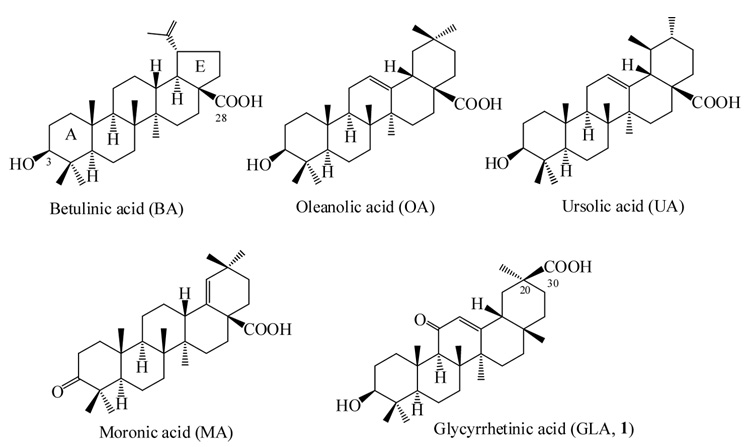

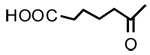

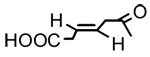

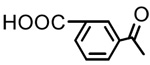

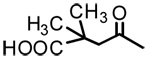

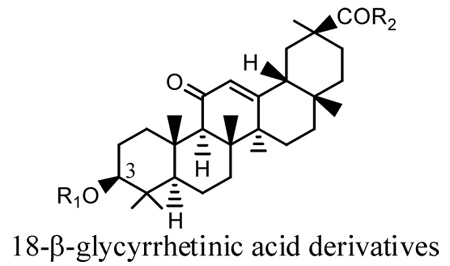

In this study, we continued our effort of searching for new compounds that possess proteasomal regulatory activity. Several triterpenes with structures similar to BA were tested for their potentials in regulating the proteasome, including glycyrrhetinic acid (GLA, 1), oleanolic acid (OA), ursolic acid (UA), and moronic acid (MA) as shown in Figure 1. The compounds were initially examined for their effect on the ChT-L activity of the proteasome. The ChT-L activity is the most critical enzymatic process in the proteasome. Genetic studies suggested that impaired proteasome ChT-L activity caused by mutations resulted in strong reduction in the degradation of proteasomal substrates (14–17), whereas impaired T-L or CA-L activity of proteasomes did not cause such a detrimental effect. Our current study indicated that among these five triterpenes, GLA is the only one that inhibited the ChT-L activity of the proteasome. GLA reduced the proteasome activity by 50% at 22.3 µM. MA did not inhibit or activate proteasome activity, possibly due to the lack of a C-3 hydroxyl group. On the contrary, BA, UA, and OA all activated the ChT-L activity of the proteasome (data not shown).

Figure 1. Chemical structure of triterpenes.

Synthesis and characterization of GLA derivatives

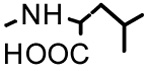

Our previous study indicated that BA derivatives with side chain modifications at the C-3 position transformed BA into proteasome inhibitors. In an attempt to increase the potency of GLA’s inhibitory effect on proteasome, a series of GLA derivatives functionalized with a variety of C-3 side chains were synthesized. The synthesis of GLA C-3 ester derivatives was accomplished by treating GLA with corresponding carboxylic acid reagents under general esterification conditions. Compounds 2–7, 9 and 11 were obtained with corresponding anhydrides in the presence of DMAP and pyridine using microwave assisted heating. The rest of the compounds (8, 10 and 12–18) were synthesized by coupling the corresponding carboxylic acid reagents in the presence of EDC•HCl/DMAP or DCC/DMAP under microwave irradiation. Compounds 19–21 were modified at the C-30 position with amide moieties with or without additional modification on their C-3 position. The synthesis of these compounds has been previously reported (18).

The structures of four of the most potent GLA derivatives, 8, 12, 17, and 18, were further confirmed with 13C NMR studies (Table 1). The spectra have shown all 30 carbons of GLA triterpene skeletons with unambiguous assignment for 7 of them based on comparison of data reported before for GLA (19). The carbon signals of C-3 ester side chain were also observed except for the three overlapping signals in compound 18. In summary, the spectra showed no or very small difference of chemical shift (all within 0.2 ppm except for the C-3) among the four compounds on the triterpene skeleton region due to its structural rigidity and stability. The C-3 chemical shifts showed more variety among these GLA esters and were found to be more than 2 ppm downfield than that in GLA.

Table 1.

13C NMR spectral data (assignment) of compounds 8, 12, 17 and 18a.

| 8 | 12 | 17 | 18 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 80.5 (C-3) | 80.9 (C-3) | 81.9 (C-3) | 81.6 (C-3) |

| 55.1 (C-5) | 55.1 (C-5) | 55.1 (C-5) | 55.1 (C-5) |

| 62.0 (C-9) | 62.0 (C-9) | 62.0 (C-9) | 62.0 (C-9) |

| 199.6 (C-11) | 199.6 (C-11) | 199.6 (C-11) | 199.6 (C-11) |

| 128.7 (C-12) | 128.7 (C-12) | 128.7 (C-12) | 128.7 (C-12) |

| 170.0 (C-13) | 170.0 (C-13) | 170.1 (C-13) | 170.2 (C-13) |

| 179.3 (C-30) | 179.3 (C-30) | 179.3 (C-30) | 179.5 (C-30) |

| 48.8 | 48.8 | 48.8 | 48.8 |

| 45.6 | 45.6 | 45.6 | 45.7 |

| 44.2 | 44.2 | 44.2 | 44.3 |

| 43.6 | 43.6 | 43.6 | 43.6 |

| 41.8 | 41.8 | 41.8 | 41.8 |

| 39.1 | 39.1 | 39.1 | 39.1 |

| 38.5 | 38.8 | 38.8 | 38.7 |

| 38.4 | 38.5 | 38.5 | 38.5 |

| 37.5 | 37.5 | 37.5 | 37.5 |

| 32.8 | 32.8 | 32.8 | 32.8 |

| 32.2 | 32.3 | 32.3 | 32.3 |

| 31.7 | 31.7 | 31.7 | 31.7 |

| 28.82 | 28.83 | 28.83 | 28.9 |

| 28.78 | 28.78 | 28.80 | 28.8 |

| 28.3 | 28.3 | 28.4 | 28.4 |

| 26.9 | 26.9 | 26.9 | 26.9 |

| 26.7 | 26.7 | 26.7 | 26.7 |

| 24.1 | 24.1 | 24.1 | 24.1 |

| 23.6 | 23.6 | 23.7 | 23.7 |

| 18.9 | 18.8 | 18.9 | 18.9 |

| 17.7 | 17.7 | 17.7 | 17.7 |

| 17.2 | 17.1 | 17.3 | 17.3 |

| 16.8 | 16.8 | 16.8 | 16.8 |

| C on C-3 side chain | |||

| 175.8 (C=O) | 174.0 (C=O) | 168.5 (C=O) | 166.2b (C=O) |

| 173.2 (C=O) | 171.5 (C=O) | 165.9 (C=O) | b |

| 34.7 (CH2CO) | 127.8 (CH=) | 134.5 (Ar-C) | 130.5c (Ar-C) |

| 34.6 (CH2CO) | 126.1 (CH=) | 133.6 (Ar-C) | c |

| 25.24 (CH2CH2CO) | 38.6 (=CHCH2) | 133.4 (Ar-C) | 129.7d (Ar-C) |

| 25.21 (CH2CH2CO) | 38.5 (=CHCH2) | 131.9 (Ar-C) | d |

| 131.3 (Ar-C) | |||

| 129.3 (Ar-C) |

Recorded in pyridine–d5 at 125 MHz.

Overlapping signals.

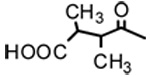

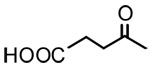

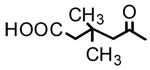

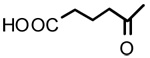

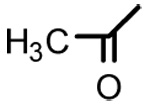

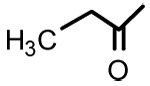

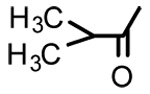

Inhibition of the proteasome by GLA derivatives

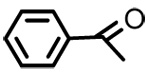

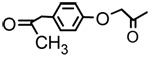

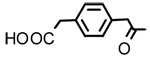

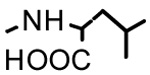

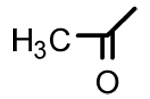

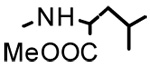

The synthesized compounds were assayed at various concentrations in order to determine their potency against the ChT-L activity (13). The known proteasome inhibitors Ac-Leu-Leu-Met-CHO (LLM-F) and lactacystin were included in the assay as controls. The results indicated that C-3 esterification of GLA increased the potency of proteasome inhibition by 3 to 100-fold when compared with unmodified GLA (Table 2). It appeared that compounds with aromatic C-3 side chains as seen in 13–18 were, in general, more potent (IC50 = 0.22 – 2.27 µM) than compounds without the aromatic side chain except for compounds 8 and 12. Compound 8 possessed an unbranched side chain similar to compounds 4 and 6. The length of the side chains of these compounds was positively correlated with the potency of the compounds against the proteasome. For example, the C-3 side chains of compounds 4, 6, and 8 increased from C4, C5, to C6, respectively, and this correlated with the improved potency of these compounds. The 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of compounds 4, 6, and 8 were 2.63, 1.39, and 0.29 µM, respectively. Compound 12, containing an unsaturated side chain, also exhibited potent inhibitory activity with IC50 equal to 0.35 µM.

Table 2.

Inhibition of the proteasome by GLA and its derivatives.

| Compounds | R1 | R2 | IC50 (µM) (ChT-L)a | IC50 (µM) (T-L)a | IC50 (µM) (Ca-L)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H | OH | 22.3 | >40 | >40 |

| 2b |  |

OH | 0.87 | - | - |

| 3 |  |

OH | 8.70 | - | - |

| 4 |  |

OH | 2.63 | - | - |

| 5 |  |

OH | 6.86 | - | - |

| 6 |  |

OH | 1.39 | - | - |

| 7 | OH | 1.93 | - | - | |

| 8 |  |

OH | 0.29 | 3.32 | 5.02 |

| 9b |  |

OH | >40 | - | - |

| 10 |  |

OH | >40 | - | - |

| 11 |  |

OH | 1.92 | - | - |

| 12 |  |

OH | 0.35 | 19.3 | 26.5 |

| 13 |  |

OH | 2.08 | - | - |

| 14 |  |

OH | 2.27 | - | - |

| 15 | OH | 1.05 | - | - | |

| 16 |  |

OH | 1.78 | - | - |

| 17 |  |

OH | 0.22 | 2.91 | 3.56 |

| 18 | OH | 0.31 | - | - | |

| 19b | H |  |

>40 | - | - |

| 20b |  |

|

>40 | - | - |

| 21b |  |

|

3.09 | - | - |

| LLM-Fc | 5.25 | >25 | 22.5 | ||

| Lactacystinc | 5.6 | >30 | >30 |

The inhibition of chymotrypsin-like (ChT-L), trypsin-like (T-L), and caspase-like (Ca-L) activities of the 20S proteasome was determined in the presence of various concentrations of the compounds as previously described (13). The value of IC50 was averaged from three independent assays.

These compounds were previously reported for their anti-HIV activities.

LLM-F and lactacystin are known proteasome inhibitors.

The free carboxylic acid moiety in the C-3 side chain was not required for proteasome inhibition as shown with compounds 11, 13, and 14, which exhibited moderate potency against proteasome. However, a free carboxylic acid moiety appeared to enhance the potency of the compound. For example, the carboxylic acid on compounds 17 and 18 might be responsible for the 10-fold increase in the anti-proteasomal activity when compared with compound 13.

Additional side chain modification at C-30 significantly decreased the potency of the C-3 derivatives of GLA. The IC50 of the C-3 derivative, 2, was 0.87 µM against the ChT-L activity of the proteasome. Addition of a C-30 side chain resulted in compound 21 that inhibited the proteasomal activity at 3.09 µM.

One of the possible reasons that bortezomib can selectively inhibit cancer cells could be due to its preferential inhibitory activity against the ChT-L activity of the proteasome (12, 20). To determine whether GLA derivatives can also preferentially inhibit the ChT-L activity of the proteasome, GLA and three of the most potent compounds, 8, 12, and 17, were tested for their effects on the T-L and CA-L activities of the proteasome. These two proteolytic activities were analyzed using the assays previously described (13). In general, the GLA derivatives were at least 10-fold less potent against the CA-L or T-L activity when compared with their anti-ChT-L activity of the proteasome (Table 2). These results suggested that all of the three tested compounds exhibited preferential inhibitory activity against the ChT-L activity of the proteasome.

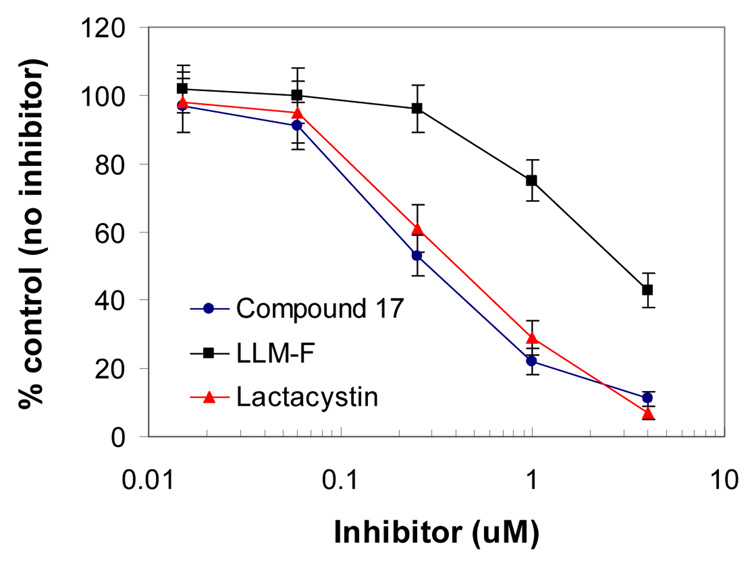

To determine whether GLA derivatives could inhibit the proteasome in the cells, 17, the most potent compound of the series, was tested in a cell-based proteasome assay previously described (13). To determine the effect of 17 on the ChT-L activity of the proteasome in living cells, MT4 cells were treated with 17 or the known proteasome inhibitors LLM-F and lactacystin. The ChT-L activity of the proteasome in the cells was analyzed using a Promega cell-based proteasome assay kit and protocol. In this study, compound 17 inhibited the ChT-L activity of the proteasome by 50% at approximately 0.25 µM (Figure 2). The inhibitory activity of 17 in the cell-based assay was comparable to the purified human 20S proteasome assay. On the other hand, lactacystin was approximately one log10 more potent in the cell-based assay when compared with that in the purified 20S proteasome assay. It is possible that the metabolites of lactacystin in the cells are responsible for the increased potency (21)

Figure 2. The GLA derivative 17 inhibited the chymotrypsin-like activity of the proteasome in MT4 cells.

A Promega cell-based proteasome assay was used to determine the effect of compound 17 on the ChT-L activity of 20S proteasome (13). The known proteasome inhibitors LLM-f and lactacystin were used as positive controls for proteasome inhibition. MT4 cells are human T cells isolated from a patient with adult T-cell leukemia. The ChT-L proteasome activity was detected as the relative light unit (RLU) generated from the cleaved substrate in the assay. The % control is derived using the formula: 100 × (RLU with test compound) / (RLU from the control without compound).

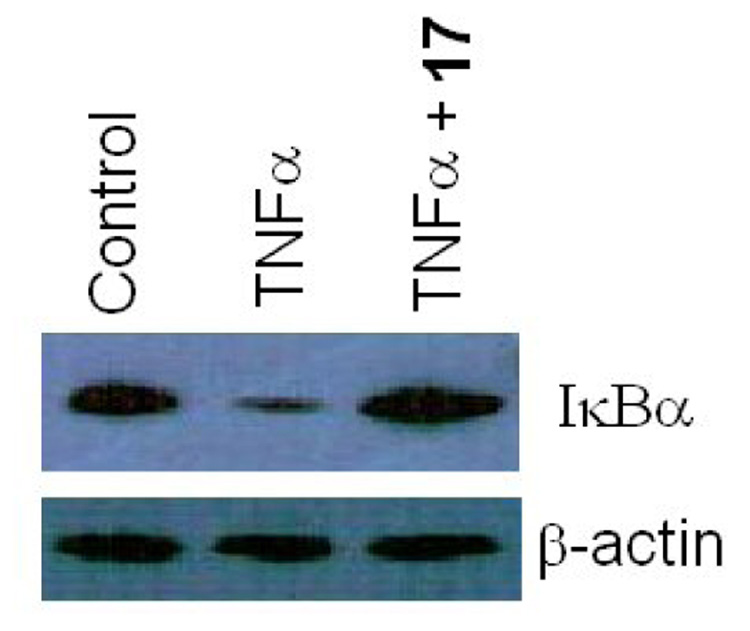

Inhibition of IκB degradation in MT4 cells

Proteasome degradation of IκBα is required for NFκB activation by tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα). To determine if compound 17 can inhibit proteasome degradation of IκBα, MT4 cells were treated with 17 (1.6 µM) for 3 hours before treating with TNFα̣ (10 ng/ml) for 30 minutes.. The cytosolic proteins were analyzed in a 12% SDS polyacrylamide gel. The proteins in the gel were transferred to a nitrocellulose paper for Western blot analyses. An IκBα monoclonal antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was used to detect IκBα̣ in the samples. TNFα treatment resulted in a significant reduction in IκBα level when compared with the control in the absence of TNFα (Figure 3) The TNFα-induced proteasome degradation of IκBα was significantly inhibited in the presence of 17. In contrast, β-actin level in the cells was not affected by 17. The results suggested that 17 specifically inhibited the proteasome in the cells.

Figure 3.

The GLA derivative 17 inhibited degradation of IκB in MT4 cells.

Conclusion

In summary, this study shows that GLA is a proteasome inhibitor, and the potency of this inhibitory activity could be markedly improved through chemical modification at the C-3 position of the compound. GLA is a natural product and has abundant natural sources. It can be obtained from the hydrolysis of the glycoside glycyrrhizic acid (GL). GL from licorice has been used as a food sweetener and in clinical treatment of HBV, where it appeared to have low toxicity and side effects (22). GLA was found to be the major component in serum after ingestion of GL (23). Therefore, development of GLA derivatives as proteasome inhibitors might have the potential to provide new therapeutics for diseases such as cancers and inflammatory diseases.

Experimental

General experimental procedures

The Biotage Initiator 2.0 was used for microwave assisted synthesis. All melting points were determined with a Fisher-Johns melting point apparatus without correction. Positive and negative FABHRMS were recorded on a Joel SX-102 spectrometer. 1H (300 MHz) and 13C (125 MHz) NMR spectra were measured on a Varian Mercury 300 spectrometer and Varian Inova 500 spectrometer, respectively. Other than as noted, all samples were dissolved in CDCl3 with TMS as internal standard. Silica gel chromatography was carried out on a Biotage Horizon Flash chromatograph system with pre-packed Si gel column. HPLC was performed on a Varian ProStar solvent delivery and PDA detector with Agilent Zorbax ODS or C-8 columns (4.6 mm × 25 cm and 9.4 mm × 25 cm for analytical and semi preparative scales, respectively). The HPLC profile of each new compound was obtained under two solvent systems (Table 3).

Table 3.

Purity of compounds determined by HPLC.

| Compound | Purity (%)a | Purity (%)d | Compound | Purity (%)a | Purity (%)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 98.9 | 94.8 | 11 | 97.5b | 97.2 |

| 3 | 95.6 | 95.1 | 12 | 96.9 | 91.6 |

| 4 | 98.1 | 99.5 | 13 | 98.7c | 99.4 |

| 5 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 14 | 96.4 | 97.8 |

| 6 | 95.4 | 98.3 | 15 | 98.4 | 98.4 |

| 7 | 98.0 | 100 | 16 | 97.1 | 96.6 |

| 8 | 91.8 | 91.2 | 17 | 96.4 | 99.5 |

| 10 | 100 | 98.4 | 18 | 99.1 | 100 |

Gradient of 88–95% of B in 22 min. Solvent A: 95% of acetonitrile/H2O and 0.045% of trifluoroacetic acid; Solvent B: acetonitrile/methanol/H2O = 85:10:5 and 0.045% of trifluoroacetic acid.

Gradient of 100% B in 30 min with same solvent system as described above.

Gradient of 90–100% B in 30 min with same solvent system as described above.

95% of acetonitrile/H2O in 30 min.

Procedure A for coupling at the C-3 hydroxyl group

A mixture of GLA, anhydride (5 ~ 10 eq.), and DMAP (1 eq.) in pyridine (anhydrous) was heated for 0.5 to 2 hr at 100 to 130°C in microwave synthesizer. The mixture was then concentrated under vacuum, re-dissolved in MeOH, and purified with Si-gel chromatography or reverse phase HPLC. The yields ranged from 30 to 50%.

Procedure B for coupling at the C-3 hydroxyl group

A solution of di-carboxylic acid (10 ~ 15 eq.), DCC (5 ~ 10 eq.), and DMAP (1 eq.) in CH2Cl2 (anhydrous) was added to GLA in pyridine and heated for 0.5 to 2 hr at 100 to 130°C in microwave synthesizer. The yields ranged from 20 to 40%.

3β-O-(2’,3’-Dimethylsuccinyl)-18-β-glycyrrhetinic acid (3)

Positive FABMS m/z 599.5 (M+H)+; HR-FABMS calcd for C36H53O7 597.3791, found 597.3783. 1H NMR δ 5.69 (1H, s, H-12), 4.52 (1H, dd, J = 4.5 Hz, J = 11.0 Hz, H-3), 2.74–2.89 (3H, m, H2α and 2×CH-COO), 1.36 (3H, s. CH3-29), 1.24–1.26 (6H, m, 2× CH3-CHCOO), 1.21 (3H, s. CH3-25), 1.16 (3H, s. CH3-23), 1.12 (3H, s. CH3-24), 0.87, 0.88 (each 3H, each s, CH3-26 and CH3-27), 0.83 (3H, CH3-28).

3β-O-Succinyl-18-β-glycyrrhetinic acid (4)

Positive FABMS m/z 571.4 (M+H)+; HR-FABMS calcd for C34H49O7 569.3478, found 569.3465. %. 1H NMR (CDCl3/Py-d5) δ 5.69 (1H, s, H-12), 4.52 (1H, dd, J = 5.7 Hz, J = 11.4 Hz, H-3), 2.75 (1H, d, J = 14.4 Hz, H2α), 2.63 (4H, s, 2×CH2CO), 1.33 (3H, s. CH3-29), 1.17 (3H, s. CH3-25), 1.10 (3H, s. CH3-23), 1.06 (3H, s. CH3-24), 0.83 (6H, s, CH3-26 and CH3-27), 0.76 (3H, CH3-28).

3β-O-(3’,3’-Dimethylglutaryl)-18-β-glycyrrhetinic acid (5)

Positive FABMS m/z 613.5 (M+H)+; HR-FABMS calcd for C37H55O7 611.3948, found 611.3930. 1H NMR (CDCl3/Py-d5) δ 5.58 (1H, s, H-12), 4.48 (1H, dd, J = 5.2 Hz, J = 11.0 Hz, H-3), 2.64 (1H, d, J = 13.3 Hz, H2α), 2.39–2.52 (4H, m, 2×COCH2), 1.29 (3H, s. CH3-29), 1.23 (3H, s. CH3-25), 1.16 (3H, s. CH3-23), 1.14, 1.13 (each 3H, each s, [CH3]2C), 1.08 (3H, s. CH3-24), 0.83, 0.84 (each 3H, each s, CH3-26 and CH3-27), 0.68 (3H, CH3-28).

3β-O-Glutaryl-18-β-glycyrrhetinic acid (6)

Positive FABMS m/z 585.5.5 (M+H)+; HR-FABMS calcd for C35H51O7 583.3635, found 583.3622. 1H NMR (CDCl3/Py-d5) δ 5.81 (1H, s, H-12), 4.61 (1H, dd, J = 5.5 Hz, J = 11.0 Hz, H-3), 2.91 (1H, d, J = 13.5 Hz, H2α), 2.46–2.55 (4H, m, 2×COCH2), 2.01–2.12 (2H, m, CH2-3’), 1.37 (3H, s. CH3-29), 1.26 (3H, s. CH3-25), 1.17 (3H, s. CH3-23), 1.09 (3H, s. CH3-24), 0.89 (6H, s, CH3-26 and CH3-27), 0.80 (3H, CH3-28).

3β-O-Diglycolyl-18-β-glycyrrhetinic acid (7)

Positive FABMS m/z 587.4 (M+H)+; HR-FABMS calcd for C34H49O8 585.3427, found 585.3433. 1H NMR (CDCl3/Py-d5) δ 5.65 (1H, s, H-12), 4.54 (1H, dd, J = 5.5 Hz, J = 11.0 Hz, H-3), 4.19, 4.18 (each 2H, each s, 2×OCH2), 2.73 (1H, d, J = 13.5 Hz, H2α), 1.27 (3H, s. CH3-29), 1.12 (3H, s. CH3-25), 1.04 (3H, s. CH3-23), 1.00 (3H, s. CH3-24), 0.78, 0.76 (each 3H, each s, CH3-26 and CH3-27), 0.70 (3H, CH3-28).

3β-O-Adipoyl-18-β-glycyrrhetinic acid (8)

Negative FABMS m/z 597.3 (M−H)−, HR-FABMS calcd for C36H53O7 597.3791, found 597.3801. 1H NMR (CDCl3/Py-d5) δ 5.71 (1H, s, H-12), 4.50 (1H, dd, J = 5.4 Hz, J = 11.5 Hz, H-3), 2.78 (1H, d, J = 13.5 Hz, H2α), 2.32–2.34 (4H, m, 2×COCH2), 1.36 (3H, s. CH3-29), 1.20 (3H, s. CH3-25), 1.13 (3H, s. CH3-23), 1.10 (3H, s. CH3-24), 0.85 (6H, s, CH3-26 and CH3-27), 0.79 (3H, CH3-28).

Glycyrrhetinic acid propionate (10)

Negative FABMS m/z 525.3 (M−H)−, HR-FABMS calcd for C33H49O5 525.3580, found 525.3586. 1H NMR δ 5.70 (1H, s, H-12), 4.52 (1H, dd, J = 5.0 Hz, J = 11.0 Hz, H-3), 2.79 (1H, d, J = 13.5 Hz, H2α), 2.32 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, CH2CH3), 1.37 (3H, s. CH3-29), 1.23 (3H, s. CH3-25), 1.17 (3H, s. CH3-23), 1.13 (3H, s. CH3-24), 1.13 (3H, d, J = 7.3 Hz, CH2CH3), 0.87, 0.88 (each 3H, each s, CH3-26 and CH3-27), 0.83 (3H, CH3-28).

Glycyrrhetinic acid isobutytate (11)

Negative FABMS m/z 539.3 (M−H)−, HR-FABMS calcd for C34H51O5 539.3765, found 539.3745. 1H NMR δ 5.71 (1H, s, H-12), 4.50 (1H, dd, J = 4.4 Hz, J = 11.1 Hz, H-3), 2.79 (1H, d, J = 13.6 Hz, H2α), 2.54 (1H, qui, J = 7.0 Hz, CH-[CH3]2), 1.37 (3H, s. CH3-29), 1.23 (3H, s. CH3-25), 1.18, 1.16 (each 3H, each d. J = 6.7 Hz, [CH3]2CH), 1.17 (3H, s, CH3-23), 1.13 (3H, s. CH3-24), 0.89, 0.87 (each 3H, each s, CH3-26 and CH3-27), 0.84 (3H, CH3-28).

3β-O-(trans-β-Hydromuconyl)-18-β-glycyrrhetinic acid (12)

Negative FABMS m/z 595.3 (M−H)−, HR-FABMS calcd for C36H51O7 595.3635, found 595.3649. 1H NMR δ 5.72 (1H, d, J = 5.0 Hz, C=H-3’), 5.69 (2H, s, C=H-2’ and H-12), 4.52 (1H, dd, J = 4.5 Hz, J = 11.5 Hz, H-3), 3.14, 3.09 (each 1H, each d, J = 5.4 Hz, CH2-COO), 2.80 (1H, d, J = 14.0 Hz, H2α), 1.37 (3H, s. CH3-29), 1.22 (3H, s. CH3-25), 1.16 (3H, s. CH3-23), 1.12 (3H, s. CH3-24), 0.87, 0.86 (each 3H, each s, CH3-26 and CH3-27), 0.83 (3H, CH3-28).

3β-O-benzoyl-18-β-glycyrrhetinic acid (13)

Negative FABMS m/z 573.3 (M−H)−, HR-FABMS calcd for C37H49O5 597.3592, found 573.3580. 1H NMR δ 8.04 (2H, d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2×H-o-Ar), 7.55 (1H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, H-p-Ar), 7.44 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2×H-m-Ar), 5.73 (1H, s, H-12), 4.76 (1H, dd, J = 5.0 Hz, J = 10.8 Hz, H-3), 2.85 (1H, d, J = 13.5 Hz, H2α), 1.40 (3H, s. CH3-29), 1.23 (3H, s. CH3-25), 1.22(3H, s. CH3-23), 1.15 (3H, s. CH3- 24), 1.04 (3H, s, CH3-26), 0.95 (3H, s, CH3-27), 0.85 (3H, CH3-28).

Glycyrrhetinic acid-4-acetylphenoxyl acetate (14)

Positive FABMS m/z 661.4 (M+H)+, HR-FABMS calcd for C41H57O7 661.4104, found 661.4097. 1H NMR δ 7.92, 6.92, (each 2H, each d, J = 9.0 Hz, 4×H-Ar), 5.68 (1H, s, H-12), 4.63 (1H, dd, J = 5.5 Hz, J = 11.0 Hz, H-3), 2.79 (1H, d, J = 14.0 Hz, H2α), 2.54 (3H, s, COCH3), 1.34 (3H, s. CH3-29), 1.20 (3H, s. CH3-25), 1.12(3H, s. CH3-23), 1.10 (3H, s. CH3-24), 0.80 (6H, s, CH3-26 and CH3-27), 0.78 (3H, CH3-28).

Glycyrrhetinic acid-m-phenylene monoacetate (15)

Positive FABMS m/z 647.5 (M+H)+; HR-FABMS calcd for C40H53O7 645.3791, found 645.3771. 1H NMR δ 7.18–7.35 (5H, m, 5×H-Ar), 5.67 (1H, s, H-12), 4.49 (1H, d, J = 4.2 Hz, H-3), 3.63 (4H, d, J = 11.0 Hz, 2×CH2-Φ), 2.76 (1H, d, J = 14.5 Hz, H2α), 1.35 (3H, s. CH3-29), 1.20 (3H, s. CH3-25), 1.13 (3H, s. CH3-23), 1.11 (3H, s. CH3-24), 0.81, 0.79 (each 3H, each s, CH3-26 and CH3-27), 0.76 (3H, CH3-28).

Glycyrrhetinic acid-p-phenylene monoacetate (16)

Negative FABMS m/z 645.3 (M−H)−, HR-FABMS calcd for C40H53O7 645.3814, found 645.3791. 1H NMR δ 7.26 (4H, s, 4×H-Ar), 5.68 (1H, s, H-12), 4.53 (1H, m, H-3), 3.63 (4H, d, J = 15.5 Hz, 2×CH2-Φ), 2.78 (1H, d, J = 13.0 Hz, H2α), 1.36 (3H, s. CH3-29), 1.21 (3H, s. CH3-25), 1.15 (3H, s. CH3-23), 1.12 (3H, s. CH3-24), 0.82 (6H, s, CH3-26 and CH3-27), 0.79 (3H, CH3-28).

Glycyrrhetinic acid monoisophthalate (17)

Negative FABMS m/z 617.3 (M−H)−, HR-FABMS calcd for C38H49O7 617.3478, found 617.3483. 1H NMR (CDCl3/Py-d5) δ 8.76 (1H, s, H-2’-Ar), 8.28, 8.18 (each 1H, each d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2×H-Ar), 7.50 (1H, t, J = 7.8 Hz, H-5’-Ar), 5.73 (1H, s, H-12), 4.78 (1H, dd, J = 4.8 Hz, J = 11.0 Hz, H-3), 2.85 (1H, d, J = 14.0 Hz, H2α), 1.38 (3H, s. CH3-29), 1.20 (3H, s. CH3-25), 1.19 (3H, s. CH3-23), 1.12 (3H, s. CH3-24), 1.04 (3H, s, CH3-26), 0.93 (3H, s, CH3-27), 0.80 (3H, CH3-28).

Glycyrrhetinic acid monoterephthalate (18)

Negative FABMS m/z 617.3 (M−H)−, HR-FABMS calcd for C36H53O7 617.3478, found 617.3464. 1H NMR (CDCl3/Py-d5) δ 8.14, 8.05 (each 2H, each d, J = 8.5 Hz, 4×H-Ar), 5.71 (1H, s, H-12), 4.74 (1H, dd, J = 4.5 Hz, J = 10.0 Hz, H-3), 2.83 (1H, d, J = 14.0 Hz, H2α), 1.35 (3H, s. CH3-29), 1.19 (3H, s. CH3-25), 1.16(3H, s. CH3-23), 1.09 (3H, s. CH3-24), 0.99 (3H, s, CH3-26), 0.91 (3H, s, CH3-27), 0.78 (3H, CH3-28).

HPLC purification of the synthesized GLA derivatives

Proteasome assay

Proteasome assay kits were purchased from Calbiochem, San Diego, CA. The effect of GLA and its analogs on the 20S proteasome activity was assayed following the protocol provided by the manufacturer. The major components of the assay mixture are human 20S proteasomes, fluorogenic peptide substrates and the proteasome activator PA28. The assay was designed to measure hydrolysis of the fluorogenic substrates Suc-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-AMC, (Z)-LLE-bNA, and Bz-VGR-AMC in the presence of the proteasome activator PA28. Suc-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-AMC is frequently used to detect the chymotrypsin-like activity of 20S proteasomes. The trypsin-like and caspase-like activities of the 20S proteasome were determined using the fluorogenic substrates Bz-VGR-AMC and (Z)-LLE-bNA, respectively. Fluorescence generated from the proteolytic reaction in the presence of various concentrations of GLA or its analogs was measured using a Bio-Tek fluorometer (Winooski, Vermont).

For proteasome inhibition, various concentrations of GLA derivatives were tested in the presence of 16 µg/ml of PA28. The known proteasome inhibitors LLM-F (Boston Biochem, Cambridge, MA, USA) and lactacystin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were used as controls for the proteasome inhibition assays. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) is defined as the inhibitory concentration that reduces the reaction rate by 50%. The velocity of reaction, ΔRFU (360/460nm)/minute, was plotted against the log-concentration of the inhibitor to determine the IC50.

Cell-based proteasome assay

To determine the effect of GLA derivatives on proteasomes in cells, a Promega cell-based assay was used in this study. MT4 cells (4,000 cells) were treated with GLA derivatives or known proteasome inhibitors in serum free medium at 37°C for 3 hours. MT4 cells are human T cells isolated from a patient with adult T-cell leukemia. MT4 cells were obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program. The drug-treated MT4 cells were incubated with the Promega Proteasome-Glo Cell-Based Assay Reagent (Promega Bioscience, Madison, WI) for 10 minutes. The chymotrypsin-like proteasome activity was detected as the relative light unit (RLU) generated from the cleaved substrate in the reagent. Luminescence generated from each reaction condition was detected with a PerkinElmer Victor-3 luminometer (Shelton, CT, USA).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Shannon Meroney-Davis for her help on editing this manuscript. The authors are grateful to Dr. George Dubay of the Department of Chemistry and Dr. Anthony Ribeiro of the NMR Spectroscopy Center of Duke University for their help and assistance on mass and NMR spectroscopy data collection.. This work was supported in part by grant from Centers for AIDS Research at Duke University (LH), the National Institutes of Health Grants AI65310 (CHC), and CA17625 and AI33066 (KHL).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dalton L. C&EN. 2002;80:37. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis E, Morris D. Mol. Cell. Endo. 1991;78:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(91)90179-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monder C, Stewart PM, Lakshmi V, Valentino R, Burt D, Edwards CRW. Endocrinol. 1989;125:1046–1053. doi: 10.1210/endo-125-2-1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buhler H, Perschel FH, Hierholzer K. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1991;1075:206–212. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(91)90268-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salvi M, Fiore C, Armanini D, Toninello A. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003;66:2375–2379. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciechanover A. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:79–86. doi: 10.1038/nrm1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hershko A, Ciechanover A. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:425–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nalepa G, Rolfe M, Harper JW. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006;5:596–613. doi: 10.1038/nrd2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rechsteiner M, Hill CP. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groll M, Heinemeyer W, Jager S, Ullrich T, Bochtler M, Wolf DH, Huber R. PNAS. 1999;96:10976–10983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.10976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kane RC, Bross PF, Farrell AT, Pazdur R. Oncologist. 2003;8:508–513. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.8-6-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kisselev AF, Callard A, Goldberg AL. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:8582–8590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509043200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang L, Ho P, Chen C-H. FEBS Letters. 2007;581:4955–4959. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heinemeyer W, Kleinschmidt JA, Saidowsky J, Escher C, Wolf DH. EMBO J. 1991;10:555–562. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07982.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gueckel R, Enenkel C, Wolf DH, Hilt W. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:19443–19452. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richter-Ruoff B, Wolf DH, Hochstrasser M. FEBS Lett. 1994;354:50–52. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01085-4. Erratum in: FEBS Lett. 1995, 358, 104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seufert W, Jentsch S. EMBO J. 1992;11:3077–3080. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05379.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu D, Sakurai Y, Chen CH, Chang FR, Huang L, Kashiwada Y, Lee KH. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:5462–5469. doi: 10.1021/jm0601912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldberg AL. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2007;35(Pt 1):12–17. doi: 10.1042/BST0350012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang J, Cheng Z-H, Yu B-Y, Cordell GA, Qiu SX. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:2337–2340. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dick LR, Cruikshank AA, Grenier L, Melandri FD, Nunes SL, Stein RL. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:7273–7276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato H, Goto W, Yamamura J, Kurokawa M, Kageyama S, Takahara T, Watanabe A, Shiraki K. Antiviral Res. 1996;30:171–177. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(96)00942-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamamura Y, Kawakami J, Santa T, Kotaki H, Uchino K, Sawada Y, Tanaka N, Iga T. J. Pharm. Sci. 1992;81:1042–1046. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600811018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]