Abstract

Homing endonucleases, also known as meganucleases, are sequence-specific enzymes with large DNA recognition sites. These enzymes can be used to induce efficient homologous gene targeting in cells and plants, opening perspectives for genome engineering with applications in a wide series of fields, ranging from biotechnology to gene therapy. Here, we report the crystal structures at 2.0 and 2.1 Å resolution of the I-DmoI meganuclease in complex with its substrate DNA before and after cleavage, providing snapshots of the catalytic process. Our study suggests that I-DmoI requires only 2 cations instead of 3 for DNA cleavage. The structure sheds light onto the basis of DNA binding, indicating key residues responsible for nonpalindromic target DNA recognition. In silico and in vivo analysis of the I-DmoI DNA cleavage specificity suggests that despite the relatively few protein-base contacts, I-DmoI is highly specific when compared with other meganucleases. Our data open the door toward the generation of custom endonucleases for targeted genome engineering using the monomeric I-DmoI scaffold.

Keywords: gene targeting, genetics, protein–DNA interactions, X-ray crystallography

Meganucleases are sequence-specific enzymes that recognize large (12–45 bp) DNA target sites. These enzymes are often encoded by introns or inteins behaving as mobile genetic elements. They produce double strand breaks (DSB) that get repaired by homologous recombination with an intron- or intein-containing gene, resulting in the insertion of the intron or intein in that particular site (1). Meganucleases are being used to stimulate homologous gene targeting in the vicinity of their target sequences with the aim of improving current genome engineering approaches, alleviating the risks due to the randomly inserted transgenes (2, 3).

The use of meganuclease-induced recombination has long been limited by the repertoire of natural meganucleases. In nature, meganucleases are essentially represented by homing endonucleases, a family of enzymes encoded by mobile genetic elements whose function is to initiate DSB induced recombination events in a process referred to as homing (4). The probability of finding a homing endonuclease cleavage site in a chosen gene is extremely low. Thus, making artificial meganucleases with custom-made substrate specificity is an intense area of research.

Sequence homology has been used to classify homing endonucleases into 5 families, the largest one having the conserved LAGLIDADG sequence motif. Homing endonucleases containing one such motif function as homodimers. In contrast, homing endonucleases containing 2 motifs are single chain proteins (5, 6). Structural information for several members of the LAGLIDADG endonuclease family indicate that these proteins adopt a similar active conformation as homodimers or as monomers with 2 separate domains (7–9). The LAGLIDADG motifs form structurally conserved α-helices tightly packed at the center of the interdomain or intermonomer interface. The last acidic residue of this LAGLIDADG motif participates in DNA cleavage by a metal ion dependent mechanism of phosphodiester hydrolysis (4).

A combinatorial and rational approach (10) has been used for engineering the overall specificity of the homodimeric meganuclease I-CreI to cleave specific sequences, such as the human RAG1 and XPC genes (11, 12). However, the resulting variants are heterodimers, consisting of 2 engineered monomers that need to be coexpressed in the targeted cell. As a consequence, 2 undesired homodimers could be produced in addition to the heterodimer, contributing to a loss of efficiency and specificity. This problem could be solved by strategies such as dimer engineering (13) or considering monomeric meganuclases.

I-DmoI is a monomeric meganuclease from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Desulfurococcus mobilis; its structure in the absence of bound DNA has been solved (7). However, there was scant information at the molecular level about I-DmoI DNA recognition and cleavage mechanisms because no structure of the enzyme-DNA complex was available. The absence of these data has hampered the use of I-DmoI as a scaffold to engineer tailored specificities. The crystal structures of I-DmoI together with the results of in silico predictions and in vivo experiments open new possibilities to engineer custom specificities, using I-DmoI as scaffold.

Results and Discussion

Overall Structure of the I-DmoI/DNA Complex.

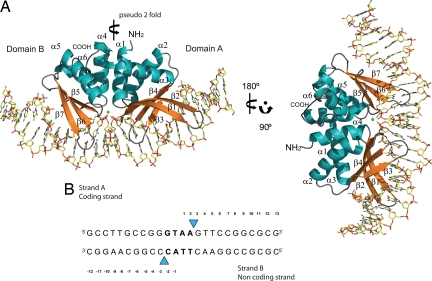

I-DmoI in complex with a 25-bp DNA was crystallized as an enzyme-substrate complex with Ca2+ and as an enzyme-product complex with Mn2+. The overall fold of I-DmoI in complex with its DNA target (Fig. 1) shows a clear pseudo 2-fold symmetry axis between the 2 LAGLIDADG helices (α1 and α4) dividing the protein into 2 domains, A (residues 5–98) and B (residues 103–195). These domains contain the typical αββαββα topology of the LAGLIDADG family, although domain B contains only 3 β-strands. Two antiparallel β-sheets, composed of strands β1–4 in domain A and β5–7 in domain B, form a concave surface with an inner cylindrical shape where the DNA molecule is accommodated. The substrate and product bound structures differ in the DNA molecule, with both strands cleaved at the expected sites in the Mn2+ bound complex (Figs. 1B and 2) (14). However, the protein moieties are very similar, Cα1–179 rmsd 0.21 Å.

Fig. 1.

Crystal structure of I-DmoI in complex with its target DNA. (A) The protein moiety is colored according to its secondary structure (α-helices are in blue, β-strands are in orange, and loops are in gray), the complex is shown in 2 different orientations. The calcium ion is shown as a green sphere. (B) Oligonucleotide used for crystallization. Throughout the text the individual bases are named with a subindex strandA or strandB indicating the DNA strand they belong to.

Fig. 2.

Detailed view of the I-DmoI active site. (A and B) Anomalous difference maps illustrate the presence of only 1 atom of calcium in the DNA bound structure (A) and 2 manganese ions in the structure of the I-DmoI product complex (B). The protein is shown in yellow and the DNA in green. (C) Schematic diagram of the hypothetical enzymatic mechanism proposed for I-DmoI. Hydrolysis of the phosphodiester bonds would follow a 2-metal ion mechanism. The first metal ion (site1, colored in yellow in 1) is bound in 1 active site and the water nucleophile (colored in red) is positioned in the central site and can attack the coding strand (in 2). The regeneration of the central water together with a second metal ion in the second site (site2, colored in cyan in 3) would enable the second attack. The D21, G20 and E117, A116 are contributed by the LAGLIDADG motifs of the enzyme.

The structure of the α-helical core of the protein scaffold is similar to the I-DmoI structure in the absence of the DNA duplex (7). However, there are differences in the overall conformation of the β-strands, the loops that join them and the connections with the core helices, that favor embracing the DNA molecule (supporting information (SI) Fig. S1). All these changes are reflected in a Cα1–179 rmsd of 1.27 Å between the I-DmoI and I-DmoI/DNA complex structure. The structure of the I-DmoI/DNA complex also depicts differences when compared with H-DreI (Fig. S2) (15), a chimerical enzyme that contains the domain A of I-DmoI fused to an I-CreI monomer (originally named E-DreI). A comparison between the wild type structure and the I-DmoI domain A of the chimera reveals subtle changes in the DNA conformation (see below).

Active Site and Cleavage Mechanism.

Divalent metal ions play an essential role in the catalysis of LAGLIDADG meganucleases. The conserved acidic residues at the active sites coordinate these divalent metal ions. The general mechanism of cleavage of the phosphodiester bonds of DNA requires a nucleophile to attack the electron deficient phosphorus atom, a general base to activate the nucleophile, a general acid to protonate the leaving group, and positively charged groups to stabilize the phosphoanion transition state.

Native electrophoresis and NMR analysis confirmed that DNA binding can occur in the absence of metal ions (Fig. S3), suggesting that they are necessary only for catalysis (SI Results) (14). The active sites of LAGLIDADG meganucleases I-SceI, I-AniI, PI-SceI, I-CreI, H-DreI and I-DmoI are structurally similar (Figs. S4 and S5). However, the precise use of bound divalent metal ions for cleavage by LAGLIDADG meganucleases, specially the monomeric ones, is still controversial (16).

The positions of the divalent metal ions in the crystal structures of the I-DmoI substrate and product complexes were analyzed by collecting anomalous diffraction data, using crystals grown in the presence of CaCl2 and MnCl2 (Fig. 2). This type of analysis with both metal ions has only been performed in I-CreI (8, 17). The binding of nonactivating calcium ions was visualized by examining the resulting anomalous difference Fourier maps. A similar strategy was followed for the enzyme-DNA complex with Mn2+ (Table S1). In contrast to I-SceI, PI-SceI and I-CreI, whose number of Ca2+ ions in the active site has been reported to be 3 or 2 (Fig. S4) (17–19), only 1 Ca2+ anomalous peak could be detected in the I-DmoI active center (Fig. 2A). The Ca2+ atom is hexa-coordinated with phosphates from both DNA strands (2AstrandA and −3CstrandB), 3 water molecules and D21 from the first LAGLIDADG motif. The additional anomalous difference study in the presence of Mn2+ demonstrated binding of 2 metal ions with equivalent occupancy, similarly to the Mg2+ positions reported for I-AniI (20) (Fig. 2B and Fig. S4). In contrast, 3 Mg2+ were reported for I-CreI (17) and H-DreI active sites (15), even though in the last case the DNA remained intact. Two of the metal ions were unshared, whereas the central one was shared between the 2 catalytic residues (Fig. S4). In I-DmoI, the central site does not show any anomalous signal and therefore the density is modeled as a water molecule. Both I-DmoI domains cooperate in metal ion binding, 1 of the Mn2+ ions is coordinated with the side chain of D21, the carbonyl of A116, the 5′phosphate of −3CstrandB, the phosphate of 2AstrandA and a water molecule outside the active site, whereas the second Mn2+ has similar interactions with the 5′phosphate of 3GstrandA, the phosphate of −2CstrandB, the main chain carbonyl of G20, the side chain of E117 in the second LAGLIDADG motif, and another water molecule outside the active site. Thus, our data suggests that I-DmoI contains only 2 metal sites, even though we cannot discard that the central site could be occupied transiently by a third metal during cleavage.

The comparison of the I-DmoI Ca2+ and Mn2+ anomalous maps indicate that only 1 of the metal sites overlaps (Fig. 2 A and B and Fig. S5). Therefore, the structural organization of the I-DmoI active site presents an asymmetry in the case of the Ca2+ bound structure, suggesting a cleavage preference for one strand during I-DmoI catalysis. A preference for one strand has also been proposed for I-SceI (21). To analyze the strand cleavage preference, we performed time-course measurements, using labeled DNA duplexes as in ref. 22 (SI Results). In contrast with the study in ref. 22, our experiment suggested a slight cleavage preference for the noncoding strand over the coding one. However, this difference lies within the experimental error hampering a solid conclusion (Fig. S6). Nevertheless, when this experiment was performed with duplexes containing a strand nicked at the cleavage site, a 2-fold cleavage preference for the coding strand over the noncoding one was observed (Fig. S6). These data suggest a hypothetical mechanism where the coding strand would be cleaved before the final reaction takes place on the noncoding strand, assuming that the nicked substrates do not favor catalysis on the coding strand (Fig. 2C). The central water could be the potential nucleophile that would initiate the reaction, after prior activation by the electropositive environment generated by the metal ions present in the active site (23). Once the coding strand would be cleaved by I-DmoI, the other catalytic metal ion in the second site would lead the cleavage of the noncoding strand after the regeneration of the central water. Thus, the enzyme would produce a nick in the DNA coding strand before the noncoding strand would be cleaved. Interestingly, the preference of strand cleavage seems to be inverted with respect to I-SceI (21). However, both enzymes seem to display a preference for cleaving first the strand that shows fewer protein contacts (Fig. S7). Although this possible mechanism is not supported by the observation of the cleavage properties of I-DmoI D21N and E117Q single mutants (24), nicked intermediates were observed in I-SceI (25) and in I-DmoI when the cleavage properties of a homodimeric I-DmoI mutant were studied using a plasmid as substrate (26). This suggests that a sequential cleavage mechanism is a possibility to consider for some of the monomeric members of the LAGLIDADG family. Other catalytic mechanisms based on 2 metal ions have been proposed for restriction enzymes such as HincII (27), whose substrate- and product-bound structures resemble those of I-DmoI active site, containing 1 Ca2+ and 4 Mn2+, respectively. Two of these Mn2+ are arranged in a similar disposition as in I-DmoI, including a site between them occupied by a water molecule.

Asymmetric DNA Target Recognition.

I-DmoI bends the DNA molecule deviating ≈40° from straight B-DNA (Fig. 3 and Fig. S2c). This angle distorts the minor groove in the middle of the DNA molecule positioning both strands in the enzyme's active site. The crystal structures reveal the asymmetric nature of the I-DmoI DNA binding cavity. Domain A contains 4 β-strands, connected by loops L1a and L2a, whereas domain B contains only 3 strands and 1 loop, L2b (Figs. 1 and 3). A detailed view of the protein-DNA contacts in the loops shows that L2a and L2b contact symmetric regions on the DNA major grooves (Fig. 3). In addition, L1a interacts with bases (6–10) in the major groove closer to the 5′ end in the noncoding strand. This protein-DNA interaction is absent in the other half of the DNA target due to the absence of the equivalent L1a loop in domain B. This implies that the DNA half associated with domain A (bases1–13) is recognized by a greater number of residues (Fig. S2a and Fig. S7). This asymmetry is also observed in the monomeric I-SceI, whereas the homodimeric I-CreI recognizes the DNA in a symmetric manner (Fig. S7). This is reflected in the nonpalindromic and pseudopalindromic nature of the DNA sequences recognized by them (SI Results).

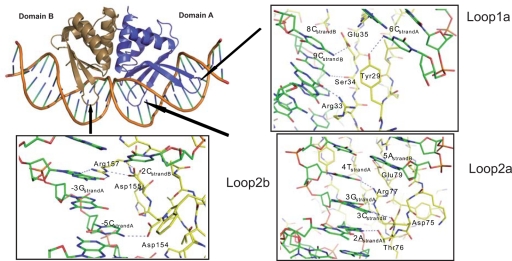

Fig. 3.

Loops involved in DNA binding by I-DmoI. The I-DmoI/DNA complex is shown in diagram representation. Domain A (violet) contains 2 loops that contact the DNA (L1a and L2a) and domain B (green) only has 1 loop (L2b) engaged in contacts with the nucleic acid. L2a and L2b are primarily associated with the central bases of the target site, and L1a is associated with bases outside that region—reflecting the asymmetry of the target recognition by I-DmoI. (Inserts) Close views of the 3 loops involved in DNA interactions. The DNA is colored in green and the protein moiety in yellow; the polar contacts in the protein-DNA interactions are displayed as dashed lines.

A detailed analysis of the protein-DNA interactions reveals few differences between the substrate- and product-bound structures (Fig. S2a). The main contacts in domain B interacting with the nucleotide bases involve R124, R126, D154, R157, and D155 (Fig. 3). R124 is positioned at a proper distance to form hydrogen bonds with the bases of −7GstrandA and −6GstrandB, whereas R126 forms a hydrogen bond with the base of −5GstrandB. The conformation of R126 side chain is influenced by the interaction with D119 that does not contact the nucleotide bases, but interacts with the phosphate backbone (data not shown). The rotamer of D119 forces a conformation of the R126, indirectly inducing the recognition of the base at −5GstrandB. The conformations and contacts of these residues are very similar in the structures of I-DmoI complexed with substrate and product. In L2b (Fig. 3), D154 makes a hydrogen bond with the base of −5CstrandA. The conformation of the D154 side chain is influenced by polar contacts with the indole ring of W128, the same network of interactions is again observed in both structures. Finally, R157 forms a hydrogen bond to the base of −3GstrandA in both structures. The conformation of R157 side chain is influenced by the conformation of D155, whose side chain also forms hydrogen bonds to the base of −2CstrandB (Fig. 3, Loop2b).

In domain A, the loop L2a presents T76 and D75, that are the only amino acids whose interactions provide specific recognition around the central 4 base pairs of the DNA (Fig. 3, Loop2a). Whereas the side chain of T76 makes a hydrogen bond with the base of 2AstrandA, D75 forms a hydrogen bond with the base of 3CstrandB. The conformation of this side chain is influenced by the presence of R77, which makes a polar contact with the base of 3GstrandA. Transversions on the DNA nucleotides at positions −1 to 4 promote major changes in I-DmoI cleavage activity (22). D75, T76, and R77 are the residues involved in hydrogen bonds with these bases (Fig. 3, Loop2a). The lack of cleavage at 65 °C is probably due to the disruption of these interactions by the transversion. The aforementioned R77 together with R81, R37, Y29, R33, E79, E35 and S34 are the remaining residues in domain A responsible for making direct contacts with the bases of the target DNA (Fig. S2a). The residue R81, that forms a hydrogen bond with 6GstrandB, is grouped with R37 and this cluster of basic residues is flanked by E79 and E35. The side chain of E79 makes a direct contact with the base of 5AstrandB and 5TstrandA, whereas the side chain of E35 contacts the base of 8CstrandB. The conformation of the E35 side chain is favored by the interactions of the side chain of S83 and the main chain of Y36 with a water molecule, which contacts the DNA backbone. Y29 together with R33 and S34 form a second group of residues clustered in space that interacts with the bases of 6CstrandA,9GstrandA and 9CstrandB respectively (Fig. 3, Loop1a). All these contacts between I-DmoI and the DNA bases seem to be responsible for target recognition, the rest of the amino acids involved in contacts make either hydrogen bonds or van der Waals interactions with the DNA backbone (Fig. S2a).

I-DmoI Versus H-DreI Domain A.

A detailed analysis of the protein-DNA interactions in I-DmoI and H-DreI domain A structures shows subtle differences in DNA contacts between the chimera and the wild type (Fig. 4 A and B and Fig. S2). H-DreI and I-DmoI present similar interactions of T76 and D75 with the central 4 base pairs. Whereas D75 makes a water-mediated hydrogen bond with 2TstrandB, and a direct one with the base of 3CstrandB, T76 forms a hydrogen bond with the base of 2AstrandA (Fig. 4C and Fig. S2a). The residues R77, R81, R37, E35, S34, and R33 in H-DreI are responsible for direct contacts with the rest of the DNA bases (Fig. 4 C and D and Fig. S2a). The side chains of R77 and R33 form hydrogen bonds with 3GstrandA and 9GstrandA in the coding strand, whereas, in the noncoding strand, R81 and R37 make hydrogen bonds with 6GstrandB and 7GstrandB, respectively. In addition, the residue E35 contacts 8CstrandB, and S34 forms hydrogen bonds with 9CstrandB and 10GstrandB. The 3 Mg2+ ions interact with the −2AstrandB and −3GstrandB bases, the phosphates of 2AstrandA, 3GstrandA, −2AstrandB and −3GstrandB, and the ribose of 2AstrandA and 2AstrandB. The specific interactions with the bases in I-DmoI and H-DreI domain A are well conserved (Fig. S2b). However, there are differences in the nonbonded contacts; H-DreI depicts a higher number of van der Waals interactions preferentially in the coding strand but also in the noncoding one. The global interbase values that describe the helical parameters of the DNA in the H-DreI and I-DmoI complexes, show differences in propeller twist, roll and tilt helical interbase pair parameters of the region shared by both enzymes (Fig. 4E). This dissimilitude is also observed in a curved global axis representation (Fig. S2c). The dissimilitude in the DNA target sequence and the other half of the enzyme being an I-CreI monomer seem to globally induce the DNA conformational change observed in domain A between H-DreI and I-DmoI.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of H-DreI and I-DmoI structures. (A) Cα trace superposition of I-DmoI and H-DreI in complex with their DNA. (B) Detailed view of the DNA moieties. (C and D) Detailed views of the loop1a and loop2a protein-DNA interactions. (E) Comparison of the helical and propeller twist values of I-DmoI and H-DreI DNAs.

I-DmoI Sequence Specificity Modeling.

We assessed in silico the specificity of I-DmoI and compared it with that of I-SceI, I-CreI and the H–DreI chimera (28). The predictions suggest that I-DmoI is the most specific of them (SI Results and Fig. S8). In addition, to evaluate the specificity of these enzymes in real genomes, putative binding sites were searched for in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Drosophila melanogaster genomes, finding none or just very few hits, respectively (SI Results and Table S2).

Sequence Specificity in Vivo.

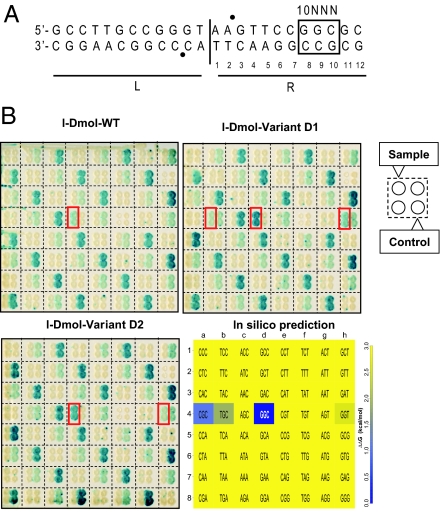

I-DmoI exhibits poor activity at 37 °C because of its thermophilic origin and therefore is not an appropriate tool for practical in vivo mesophilic applications. However, 2 mutants, D1 (I52F, L95Q) and D2 (I52F, A92T, F101C), have been produced previously with enhanced activity at 37 °C (29). A thermodynamic analysis showed a significant destabilization of these mutants, that together with the increase in activity could compromise the enzyme specificity increasing its toxicity. To analyze this issue, the cleavage specificities of these variants and the wild type, were studied in vivo, using a previously described yeast assay that monitors meganuclease-induced recombination at 37 °C (10, 30). The cleavage of all possible base pair combinations at positions 8, 9 and 10 of the right half (R-10NNN) of the target DNA was assayed (64 substrates in total) (Fig. 5A). This triplet is recognized by domain A and is a region of abundant protein-DNA contacts. The detailed interaction map of this region includes polar contacts of R33 with the 9GstrandA base, of S34 carbonyl main chain with 9CstrandB, of S34 main chain amide with 10GstrandB base; and of E35 side chain with 8CstrandB pirimidine ring. The results show that changes in the 8,9,10 triplets are not supported by I-DmoI at 37 °C in vivo, and we could detect only the residual cleavage of the wild type R-10GGC (8GstrandA, 9GstrandA, and 10CstrandA) target (Fig. 5B). This target remained the preferential recognition site for both mesophilic variants. However, D1 supports 2 variations, G to T at position 8strandA (R-10TGC) and C to T at position 10strandA (R-10GGT). D2 supports only one, C to T at position 10strandA (R-10GGT). These results are in good agreement with the in silico calculations for the I-DmoI structure (Fig. 5B and SI Results). The wild type DNA triplet displays the best interaction energy and the other two weakly positives correspond to the other 2 experimental hits (R-10TGC and R-10GGT), which only appear experimentally when the mutants with enhanced activity at 37 °C are tested. In silico this is equivalent to consider a higher binding energy cut-off. An extra positive triplet found in silico (R-10CGC) could not be confirmed experimentally. Consequently, the amino acids contacting the R-10NNN domain of the target seem to be essential determinants in I-DmoI target recognition.

Fig. 5.

In vivo cleavage patterns. (A) I-DmoI recognition site divided in 2 halves, L (Left) and R (Right). Sixty-four targets were derived from the natural I-DmoI target differing only by 3 base pairs at positions 8, 9, and 10 on the R half of the target (R-10NNN). Bullets (●) indicate cleavage positions. (B) Cleavage activities of I-DmoI wild type and of 2 mesophilic I-DmoI variants (D1, D2). The 64 targets are identified in Lower Right by the 5′-NNN-3′ top strand sequence of the nucleotides 8, 9, and 10. The dark blue box is the natural target. (Upper Left) Profile of I-DmoI. (Upper Right) Profile of I-DmoI D1. (Lower Left) Profile of I-DmoI D2. Targets cleaved by the samples are boxed in red. Negative cleavage controls were for mild cleavage: 1a, 1d, 1g, …; medium cleavage : 1b, 1e, 1h, …; and strong cleavage: 1c, 1f, 2a, …. (Lower Right) In silico binding pattern predicted by FoldX. The target triplet is shown inside each cell. For clarity purposes all values >3 kcal/mol are in yellow (see SI Materials and Methods).

Conclusions

Our data suggest a sequential mechanism for the catalytic mechanism and provide valuable preliminary information to alter I-DmoI specificity to generate custom meganucleases, using this scaffold. We have used structural data to engineer the specificity of the homodimeric I-CreI protein. Using a statistical approach, we could also infer the role of individual contacts between the protein and the target (10, 30). First, we locally engineered subdomains of the I-CreI DNA binding interface to cleave DNA targets differing from the I-CreI target by a few consecutive base pairs. Then, mutations from locally engineered variants were combined into heterodimeric mutants to cleave chosen targets differing from the I-CreI cleavage site over their entire length (10, 30). During the first step, engineering relied essentially on the mutation of residues shown to contact the DNA target (31, 32). The structure of the I-DmoI/DNA complex opens new possibilities for a similar approach to that used with I-CreI, which could present advantages over the I-CreI scaffold. The previously described I-CreI engineered derivatives are heterodimers. Therefore, they are obtained by coexpression of 2 different monomers in the target cell (10, 30, 33), resulting in the formation of 3 molecular species (the heterodimer and 2 homodimers). Studies with heterodimeric Zinc Finger Nucleases (34, 35) showed that such homodimeric by-products can be cytotoxic. As a monomeric homing endonuclease, the I-DmoI protein could bypass this drawback. Furthermore, I-DmoI, and its mesophilic mutants, seems to have a very narrow specificity. In recent reports (10, 30), we showed that the I-CreI D75N meganuclease mutant has a narrow target specificity, showing strong cleavage for only 3 targets of 2 similar collections of 64 targets derived from the wild-type I-CreI target. The narrow cleavage pattern of the I-DmoI D1 and D2 variants suggests that I-DmoI is at least as selective as I-CreI. The induction of homologous gene targeting by sequence specific endonuclease is seen today as an emerging technology with many applications (36). However, and increasing emphasis is being set on the specificity of such endonucleases (36–38) to meet the high requirements of therapeutic applications. The scaffold of I-DmoI could be a very good starting point to engineer very specific endonucleases for such purposes.

Materials and Methods

Full details are available in SI Materials and Methods.

Structure Solution.

Protein expression, purification, protein-DNA complex formation and crystallization are described in ref. 39. The structure of the protein-DNA complex was determined using the SAD method and refined against native datasets (see Fig. S9).

Construction of Target Clones.

The nonpalindromic 24bp DNA in Fig. 1B contains the I-DmoI target. The 64 degenerated targets were obtained by mutating nucleotides at position 8, 9, and 10 in strand A (Fig. 5A).

Yeast Screening.

I-DmoI WT and the 2 I-DmoI mesophilic variants, D1 and D2 (29), were screened against the 64 I-DmoI derivated targets (right half, positions 10, 9, 8) by mating meganuclease expressing yeast clones with yeast strains harboring a reporter system as described in ref. 10.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank the staff at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility and Swiss Light Source for helpful advice during data collection. This work was supported by a long-term European Molecular Biology Organization fellowship (M.J.M.), partly by a Centre de Regulació Genòmica-Novartis fellowship (A.A.), Ikerbasque (F.J.B.), European Union MEGATOOLS (LSHG-CT-2006-037226), and Ministerio de Ciencia e Inovación Grant BFU2007-30703-E.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Base, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes 2VS7 and 2VS8).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0804795105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Thierry A, Dujon B. Nested chromosomal fragmentation in yeast using the meganuclease I-Sce I: A new method for physical mapping of eukaryotic genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5625–5631. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.21.5625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choulika A, Perrin A, Dujon B, Nicolas JF. Induction of homologous recombination in mammalian chromosomes by using the I-SceI system of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1968–1973. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hacein-Bey-Abina S, et al. LMO2-associated clonal T cell proliferation in two patients after gene therapy for SCID-X1. Science. 2003;302:415–419. doi: 10.1126/science.1088547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chevalier BS, Stoddard BL. Homing endonucleases: Structural and functional insight into the catalysts of intron/intein mobility. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:3757–3774. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.18.3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacquier A, Dujon B. An intron-encoded protein is active in a gene conversion process that spreads an intron into a mitochondrial gene. Cell. 1985;41:383–394. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalgaard JZ, Garrett RA, Belfort M. A site-specific endonuclease encoded by a typical archaeal intron. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5414–5417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silva GH, Dalgaard JZ, Belfort M, Van Roey P. Crystal structure of the thermostable archaeal intron-encoded endonuclease I-DmoI. J Mol Biol. 1999;286:1123–1136. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chevalier BS, Monnat RJ, Jr, Stoddard BL. The homing endonuclease I-CreI uses three metals, one of which is shared between the two active sites. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:312–316. doi: 10.1038/86181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spiegel PC, et al. The structure of I-CeuI homing endonuclease: Evolving asymmetric DNA recognition from a symmetric protein scaffold. Structure. 2006;14:869–880. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnould S, et al. Engineering of large numbers of highly specific homing endonucleases that induce recombination on novel DNA targets. J Mol Biol. 2006;355:443–458. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gouble A, et al. Efficient in toto targeted recombination in mouse liver by meganuclease-induced double-strand break. J Gene Med. 2006;8:616–622. doi: 10.1002/jgm.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Redondo P., et al. Molecular basis of xeroderma pigmentosum group CDNA recognition by engineered meganucleases. Nature. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nature07343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fajardo-Sanchez E, Stricher F, Paques F, Isalan M, Serrano L. Computer design of obligate heterodimer meganucleases allows efficient cutting of custom DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2163–2173. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dalgaard JZ, Garrett RA, Belfort M. Purification and characterization of two forms of I-DmoI, a thermophilic site-specific endonuclease encoded by an archaeal intron. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:28885–28892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chevalier BS, et al. Design, activity, and structure of a highly specific artificial endonuclease. Mol Cell. 2002;10:895–905. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00690-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stoddard BL. Homing endonuclease structure and function. Q Rev Biophys. 2005;38:49–95. doi: 10.1017/S0033583505004063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chevalier B, et al. Metal-dependent DNA cleavage mechanism of the I-CreI LAGLIDADG homing endonuclease. Biochemistry. 2004;43:14015–14026. doi: 10.1021/bi048970c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moure CM, Gimble FS, Quiocho FA. Crystal structure of the intein homing endonuclease PI-SceI bound to its recognition sequence. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:764–770. doi: 10.1038/nsb840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moure CM, Gimble FS, Quiocho FA. The crystal structure of the gene targeting homing endonuclease I-SceI reveals the origins of its target site specificity. J Mol Biol. 2003;334:685–695. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bolduc JM, et al. Structural and biochemical analyses of DNA and RNA binding by a bifunctional homing endonuclease and group I intron splicing factor. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2875–2888. doi: 10.1101/gad.1109003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moure CM, Gimble FS, Quiocho FA. Crystal structures of I-SceI complexed to nicked DNA substrates: Snapshots of intermediates along the DNA cleavage reaction pathway. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3287–3296. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aagaard C, Awayez MJ, Garrett RA. Profile of the DNA recognition site of the archaeal homing endonuclease I-DmoI. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1523–1530. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.8.1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia-Viloca M, Gao J, Karplus M, Truhlar DG. How enzymes work: Analysis by modern rate theory and computer simulations. Science. 2004;303:186–195. doi: 10.1126/science.1088172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lykke-Andersen J, Garrett RA, Kjems J. Mapping metal ions at the catalytic centres of two intron-encoded endonucleases. EMBO J. 1997;16:3272–3281. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.3272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perrin A, Buckle M, Dujon B. Asymmetrical recognition and activity of the I-SceI endonuclease on its site and on intron-exon junctions. EMBO J. 1993;12:2939–2947. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05956.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silva GH, Belfort M, Wende W, Pingoud A. From monomeric to homodimeric endonucleases and back: Engineering novel specificity of LAGLIDADG enzymes. J Mol Biol. 2006;361:744–754. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Etzkorn C, Horton NC. Mechanistic insights from the structures of HincII bound to cognate DNA cleaved from addition of Mg2+ and Mn2+ J Mol Biol. 2004;343:833–849. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schymkowitz J., et al. The FoldX web server: An online force field. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W382–W388. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prieto J, et al. Generation and analysis of mesophilic variants of the thermostable archaeal I-DmoI homing endonuclease. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:4364–4374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706323200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith J, et al. A combinatorial approach to create artificial homing endonucleases cleaving chosen sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:e149. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jurica MS, Monnat J, Jr, Stoddard BL. DNA recognition and cleavage by the LAGLIDADG homing endonuclease I-CreI. Mol Cell. 1998;2:469–476. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80146-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chevalier B, Turmel M, Lemieux C, Monnat RJ, Jr, Stoddard BL. Flexible DNA target site recognition by divergent homing endonuclease isoschizomers I-CreI and I-MsoI. J Mol Biol. 2003;329:253–269. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00447-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arnould S, Perez C, Cabaniols JP, Smith J, Gouble A. Engineered I-CreI derivatives cleaving sequences from the human XPC gene can induce highly efficient gene correction in mammalian cells. J Mol Biol. 2007;371:49–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bibikova M., Beumer K., Trautman J. K., Carroll D. Enhancing gene targeting with designed zinc finger nucleases. Science. 2003;300:764. doi: 10.1126/science.1079512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beumer K, Bhattacharyya G, Bibikova M, Trautman JK, Carroll D. Efficient gene targeting in Drosophila with zinc-finger nucleases. Genetics. 2006;172:2391–2403. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.052829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paques F, Duchateau P. Meganucleases and DNA double-strand break-induced recombination: Perspectives for gene therapy. Curr Gene Ther. 2007;7:49–66. doi: 10.2174/156652307779940216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Szczepek M, et al. Structure-based redesign of the dimerization interface reduces the toxicity of zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:786–793. doi: 10.1038/nbt1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller JC, et al. An improved zinc-finger nuclease architecture for highly specific genome editing. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:778–785. doi: 10.1038/nbt1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Redondo P, Prieto J, Ramos E, Blanco FJ, Montoya G. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis on the homing endonuclease I-Dmo-I in complex with its target DNA. Acta Crystallogr F. 2007;63:1017–1020. doi: 10.1107/S1744309107049706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.