Abstract

Envenomation by marine creatures is common. As more people dive and snorkel for leisure, the incidence of envenomation injuries presenting to emergency departments has increased. Although most serious envenomations occur in the temperate or tropical waters of the Indo‐Pacific region, North American and European waters also provide a habitat for many stinging creatures. Marine envenomations can be classified as either surface stings or puncture wounds. Antivenom is available for a limited number of specific marine creatures. Various other treatments such as vinegar, fig juice, boiled cactus, heated stones, hot urine, hot water, and ice have been proposed, although many have little scientific basis. The use of heat therapies, previously reserved for penetrating fish spine injuries, has been suggested as treatment for an increasing variety of marine envenomation. This paper reviews the evidence for the effectiveness of hot water immersion (HWI) and other heat therapies in the management of patients presenting with pain due to marine envenomation.

Keywords: bites, stings, marine toxins, heat, pain

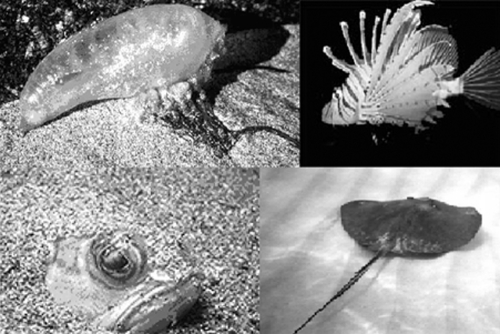

Almost 2000 ocean species are either venomous or poisonous to humans. As more people dive and snorkel for leisure, the incidence of envenomation injuries presenting to emergency departments has increased.1 Between 40 000 and 50 000 marine envenomations occur worldwide each year.2 Coastal emergency departments regularly see patients who present after marine envenomation, although some incidents occur “inland” as a result of stings from fish kept as pets.3,4 Although most serious envenomations occur in the temperate or tropical waters of the Indo‐Pacific region, North American and European waters also provide a habitat for many stinging creatures.5,6 Envenomations in European waters are most commonly caused by Weever fish, scorpion fish, and coelenterates such as the Portuguese man‐of‐war or other jellyfish (fig 1). Marine envenomations can be classified as either surface stings (erythema, vesicles, urticaria) or puncture wounds (bites, stings) (appendix 1).

Figure 1 Venomous marine creatures. Clockwise from top left: Physalia, lionfish, stingray, lesser Weever fish.

Specific antivenom is available for the treatment of stonefish and box jellyfish stings. Otherwise, various treatments have been proposed for marine envenomation, although many have little scientific basis. Traditional remedies have included vinegar, fig juice, boiled cactus, heated stones, hot urine, hot water, and ice.5,7 Established national and international guidelines advocate the use of vinegar and application of cold for selected types of marine envenomation. The use of heat therapy, traditionally in the form of HWI has previously been reserved for envenomation by penetrating fish stings. More recently, there has been increased interest in applying this treatment to surface stings.8,9,10,11 The use of HWI or heat application as the initial treatment for “puncture”‐type fish stings has a long history. The earliest record of the effective use of heat in the treatment of Weever fish stings was in 1758. It was noted that German fishermen found a hot poultice “a most effective cure”.7 Standard advice is to submerge the affected part in hot water at as high a temperature as the patient can tolerate for 30–90 minutes.7

In this article, we review the evidence for the effectiveness of HWI or other heat therapies in the management of patients presenting with pain due to marine envenomation.

Search strategy

We searched the databases MEDLINE (including PRE‐MEDLINE), EMBASE, and CINAHL using the OVID interface with the following search strategy: ((hot water or heat).mp. or exp *Heat/) and (exp *Fishes/or exp *“Bites and Stings”/or fish sting.mp. or exp *Fishes, Poisonous/or exp *Fish Venoms/or exp *Jellyfish/or envenomation.mp.)

We also searched the Cochrane database injury, wound, and anaesthesia section in full, the British National Formulary and Toxbase databases for national guidelines, and the internet, using the ‘Google' search engine. The bibliographies of the articles obtained were then manually searched. The results are outlined below. Unpublished work and conference presentations were researched by communication with people with expertise in the field of marine envenomation.

The articles were graded by study design according to the levels of evidence summarised in appendix 2.

Results

The published evidence on this topic ranges from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to personal communications to journals. Results of studies and published articles are presented in the order of their evidence level.

Level I evidence: randomised controlled/paired trials

Two RCTs and one randomised paired comparison trial have been published addressing the use of heat as a treatment for marine envenomation. These studies look at nematocyst‐type stings. The results are summarised in table 1.

Table 1 Published randomised trials on the use of heat in the treatment of marine envenomation.

| Study | N/Type | Group | Intervention | Outcome | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thomas et al8 | 133 | Swimmers with box | Pain scores at 0, 5 and 10 minutes: | Poor randomisation technique | |

| 2001 | Randomised | jellyfish (Carybdea | Hot pack v cold pack | 42.3 to 31.3 to 27.5* v 38.3 to 32.8* to 36.2 | due to practical difficulties |

| controlled | alata) stings | Cold pack v placebo | 38.3 to 32.8* to 36.2 v 38.6 to 37.7 to 38.2 | Inadequate blinding | |

| trial | Hot pack v placebo | 42.3 to 31.3* to 27.5* v 38.6 to 37.7 to 38.2 | Altered outcome measures | ||

| (*p<0.05) | after starting trial (changed | ||||

| Cessation of pain—odds ratio (95% CI): | definition of pain cessation) | ||||

| Hot pack | 5.2 (1.3 to 22.8) | Not analysed on intention to | |||

| Cold pack | 0.5 (0.1 to 2.1) | treat basis | |||

| Placebo | 1.0 | ||||

| Nomura et al9 | 25 (50 stings) | Volunteers with box | Pain scores at 0, 4, 20 minutes | Potentially active substances | |

| 2002 | Randomised | jellyfish (Carybdea | Hot water immersion | 3.6 to 2.1* to 0.2* | (papain or vinegar) used |

| paired | alata) stings | Control | 3.7 to 3.2 to 1.8 | as controls | |

| trial | (* p<0.001) | No placebo | |||

| Loten et al10 | 96 | Swimmers with blue | Percentage with reduced pain 10, 20 minutes | Possible allocation blas, | |

| 2006 | Randomised | bottle (Physalia) | Hot water immersion | 53%*, 87%** | suggested by the baseline |

| controlled | stings | Ice pack | 32%, 33% | imbalance in initial pain | |

| trial | (* p = 0.039; **p = 0.002) | severity |

Thomas et al measured the analgesic effect of hot and cold packs on box jellyfish (Carybdea alata) stings in 133 swimmers in Hawaii.8 These particular jellyfish do not have a lethal sting, but cause significant pain, lasting from 20 minutes to 24 hours and resolving spontaneously. This study looked at the short term effects (5–15 minutes following application) of hot and cold packs and placebo. The main finding was that heat reduced pain scores at 5 and 10 minutes after application. There was also a significantly higher odds ratio (5.2) for complete cessation of pain with heat compared with placebo. There are some methodological flaws in this study (see table 1) and the authors themselves noted the borderline clinical significance of their findings.

In a randomised paired trial Nomura et al compared HWI with standard therapy (papain and vinegar) for acute Hawaiian box jellyfish stings inflicted on 25 healthy volunteers.9 Both arms of each volunteer were stung, with one treated by HWI and the other with either vinegar or papain. The authors found that pain scores on a visual analogue scale were lower with HWI at 4 and 20 minutes, with similar baseline levels. One methodological flaw was the use of two different potentially active substances in the control group. The results could also have been biased by distraction, as volunteers were asked to gauge pain scores from two simultaneous stings.

Loten et al10 have recently published an RCT of HWI versus ice packs for pain relief in Physalia stings. Forty nine patients received HWI and 47 received icepacks. They found that hot water group reported len pain after 10 and 20 minutes of treatment. The trial was stopped after the halfway interim analysis because HWI was shown to be more effective (p = 0.002).

Researchers from Sydney, Australia, recently completed a randomised crossover trial comparing hot showers and icepacks for the treatment of Physalia (Portuguese man‐of‐war/bluebottle) envenomation in a beach setting.11 The usual local practice for the treatment of these stings was cold pack application. Fifty four adults were randomised to hot shower or cold pack application, with 27 in each arm of the trial. A total of 24 subjects completed crossover. There was no significant difference in pain scores between the two treatments in each individual stage of the trial. Combined results from both stages showed that hot showers reduced total treatment time and provided greater overall pain reduction when measured using a visual analogue score. Complete cessation of pain was reported by 48% of patients treated with hot showers, significantly more than the 29% who were pain free after cold pack treatment. The lack of a blinding and follow up are the main methodological flaws of this study (see table 2).

Table 2 Published randomised trial .

| Paper | N/type | Group | Intervention | Outcome | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bowra et al11 | 54 | Swimmers with | Pain score reduction: | No blinding | |

| 2002 | Prospective | Physalia stings | Hot shower | 82.1%* (4.3) | No controls |

| randomised | Cold pack | 65.6% (6.0) | Crossover in 24/54 | ||

| crossover | Pain cessation: | cases | |||

| trial | Hot shower | 48%** | Lack of follow up | ||

| Cold pack | 29% | ||||

| Total treatment time | |||||

| Hot shower | 11.0* (0.9) min | ||||

| Cold pack | 14.6 (1.6) min | ||||

| (*p<0.05; **p<0.01) |

Level II evidence: experimental paired/crossover study

An early paper details a small experimental trial in which six healthy volunteers each received an injection of extracted, concentrated stingray venom into one finger of each hand.6 They then placed one hand in cold, and the other in hot water. Pain was relieved within five minutes by HWI but exacerbated by cold water immersion. Crossover was performed with five of the volunteers with the same findings. Pain was completely relieved after 30 minutes of HWI. This study is summarised in table 3.

Table 3 Experimental study of the efficacy of hot water immersion following evenomation.

| Paper | N/group/type | Intervention | Outcome | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russell6 | 6 volunteers (each | Initial pain relief: | Small numbers | |

| 1958 | received 2 injections | No randomisation. Atypical crossover | ||

| of stingray venom) | HWI | 6/6 | (Initially 6 in each arm, then all 12 to | |

| Cold water | 0/6 | HWI simultaneously, then alternating | ||

| with cold water) | ||||

| Experimental paired trial | Complete analgesia | No statistical analysis | ||

| with crossover | at 30 minutes: | |||

| HWI | 5/5 |

HWI, hot water immersion.

Level III evidence: cases series

Six papers report on 259 cases of marine envenomation, including puncture‐type stings from stingrays or stinging fish and nematocyst stings from jellyfish. Of the 135 cases treated with hot water, where follow up was complete, 122 patients reported a reduction in pain (table 4).

Table 4 Case series of marine envenomation.

| Paper | N/group/type | Intervention | Outcome | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isbister13 | 15 from 22 cases | HWI | Analgesic effectiveness: | Includes some retrospective data |

| 2001 | Mixed species fish stings | Complete 11/15 | (7 cases) | |

| Prospective case series | Partial 1/15 | No standardised treatment | ||

| None 1/15 | No pain scale | |||

| Unknown 2/15 | ||||

| Briars and | 24 cases + 23 extra cases | HWI | 23/24 reported decreased pain | Published as letter |

| Gordon14 | by survey | Methodological details lacking | ||

| 1992 | Weever fish stings | Survey has potential for bias | ||

| Prospective case series | Follow‐up survey: | No pain scale used | ||

| with survey | 39 respondents stated pain reduced | |||

| by HWI | ||||

| Yoshimoto et al12 | 60 from 113 | Heat | Pain relief in 23/25 cases | Retrospective |

| 2002 | Swimmers with jellyfish stings | application | (OR 11.5; p = 0.08) | No control group |

| Retrospective case series | Hot shower | Pain relief in 22/23 cases | Significant number of incomplete | |

| (OR 22.0; p = 0.0485) | medical records | |||

| Halpern et al15 | 3 Weever fish stings | HWI | Pain relieved in 3/3 cases | Retrospective |

| 2002 | Retrospective case series | Small numbers | ||

| Other analgesics given | ||||

| No pain scores used | ||||

| Trestrail and | 23 | HWI | Pain relieved in 15/15 cases | Retrospective |

| Al‐Mahasneh3 | Lionfish stings | No pain scale | ||

| 1989 | Retrospective case series | Missing data | ||

| Kizer et al4 | 51 | HWI | Complete pain relief in 30/38 cases | Retrospective |

| 1985 | Fish stings (45 lionfish, | Complications | Missing data | |

| 6 scorpion‐fish) | 4 infections, 1 burn | No pain scale | ||

| Retrospective case series |

Level IV evidence: review articles, summary papers, guidelines and letters

Five review articles on marine envenomation have discussed the use of HWI (table 5). Guidelines and summary papers on the treatment of marine envenomation tend to advocate the use of HWI for all puncture‐type fish stings, but do not otherwise recommend its routine use.20,21,22,23 A total of eight published letters to journals discuss the use of HWI as a treatment for marine envenomation. There is a broad consensus among correspondents that HWI has a beneficial effect on pain levels in certain circumstances.7,24,25,26,27,28,29,30 Two published letters caution against certain aspects of this treatment method.31,32

Table 5 Non‐systematic reviews on marine envenomation.

| Paper | Advice relating to hot water immersion (HWI)/heat application | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Fenner16 | HWI for stingray and fish spine stings, | Literature review of marine envenomation |

| 2002 | for analgesic effect | No methodology, critical appraisal or meta‐analysis |

| Fenner17 | HWI for stingray and stonefish stings, | Literature review of marine envenomation |

| 2000 | for analgesic effect | No methodology, critical appraisal or meta‐analysis |

| Hawdon and | HWI for stonefish and “other stinging | Literature review of marine envenomation |

| Winkel18 | fish”; for analgesic effect | No methodology, critical appraisal or meta‐analysis |

| 1997 | ||

| Meyer19 | HWI for stingray injuries, for analgesic | Literature review of stingray injuries |

| 1997 | effect | No methodology, critical appraisal or meta‐analysis |

| Auerbach5 | HWI for puncture wounds of stingray, | Literature review of marine envenomation |

| 1991 | scorpion fish, stonefish, sea‐urchin, | No methodology, critical appraisal or meta‐analysis |

| starfish, catfish, Weever fish, | ||

| for analgesic effect | Clear treatment algorithm proposed. |

Discussion

Evidence supporting use of HWI

Hot water immersion is a widely used and accepted treatment for fish‐spine stings, although there have not been any RCTs to date. The evidence for the treatment of puncture‐type stings by this method comes from one small experimental study6 and a total of 99 reports of its effective use in 110 cases from several papers.3,4,13,14,15 This evidence has led to recommendation of this treatment method by organisations such as the International Life Saving Federation23 and the British Marine Life Study Society.33 The use of HWI is advised in toxicology guidelines such as Toxbase22 and the BNF21 and is supported in all five published review articles on marine envenomation.5,16,17,18,19

There is less widespread support for the use of HWI for nematocyst stings in these same guidelines and reviews, yet there is mounting evidence that HWI is also effective for this type of sting. Three randomised trials8,9,10 and one abstracted RCT11 of jellyfish and Physalia stings found hot water or heat therapy to be more effective than placebo or cold packs at relieving pain. Also, in a case series pain was reported to be relieved in 23 of the 25 patients treated by heat therapy.12 There is recent evidence (2001/02) for the use of hot water therapy in nematocyst stings. Revisions of guidelines issued by several international life saving and resuscitation organisations mention the use of HWI for selected surface‐type stings such as Physalia, however, none advise this treatment before the more traditional first aid policies of selective use of vinegar to inactivate nematocysts, immobilisation, and application of ice packs.23,33,34,35,36,37

Mechanism of action of HWI

So how might HWI or heat application work as a treatment marine envenomation? Two theories have been proposed.7,9,28,38 Marine venoms consist of multiple proteins and enzymes, and there is evidence that these become deactivated when heated to temperatures above 50 °C.19 A long‐held view is that deactivation of these heat labile proteins by direct heat application leads to inactivation of the venom. Carrette et al investigated the effect of temperature on lethality of venom from Chironex fleckeri. They showed that at temperatures over 43 °C, venom lost its lethality more rapidly the longer the exposure time. However, no significant loss of lethality was seen after exposure to temperatures less than 39 °C.39 The theory of deactivation has been questioned by authors who contend that such direct inactivation would require temperatures so high as to result in burns and tissue necrosis in the patient.14,38 An alternative theory is that HWI causes modulation of pain receptors in the nervous system leading to a reduction in pain. Established pain hypotheses such as the gate control theory and the diffuse noxious inhibitory control theory have been proposed as possible mechanisms of action for HWI.38 Although marine envenomation is more commonly associated with warmer regions than the UK, the relevance of this topic and of HWI is not restricted to tropical and subtropical areas. Of the 146 cases of puncture‐type stings included in the reported cases series, a total of 47 were due to Weever fish in European waters and 68 were caused by fish kept in tanks by aquarists (see table 4). Cases of Weever fish stings in which HWI was not used, and in which pain persisted for several days have been reported from Wales.40 Victims who are aware of the benefits of HWI may choose not to seek medical advice. However, it is important that emergency physicians are aware of treatment options for those patients who do present to hospital.

Methods of application of HWI

There is only a single recorded case of significant thermal burn from over 200 cases of the use of HWI.4 This treatment modality appears to be safe when used sensibly. It is an inexpensive, and as there is reasonable evidence that it can relieve pain after a variety of types of fish sting. The most commonly referenced methods of application are thermal packs, basins of hot water, and hot showers. The choice is likely to be determined by the availability of each close to the location of envenomation. Showering may have a theoretical advantage in that it may wash off any remaining stinging cells, as well as having the ability to vary the temperature, and to continue the heat application until pain relief is achieved. Application of hot, but not scalding, water (42–45 °C) for 30–90 minutes or until the pain resolves, seems to be standard advice, though some patients may find such temperatures difficult to tolerate.41 Our advice is to use the highest temperature that can be applied safely and that is tolerable.

Current published evidence seems to support the use of HWI in the treatment of non‐life threatening marine envenomation, alongside other established first aid measures.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank S Robinson and G Campbell‐Hewson for their help and advice in the preparation of this paper.

Abbreviations

HWI - hot water immersion

Appendix 1 Types of marine envenomation

Surface stings (nematocysts)

This mechanism of envenomation involves a system of venom glands able to discharge a structure that penetrates the victim and carries the venom through a tube. The glands are found in the Portuguese man‐of‐war (Physalia), fire corals, anemones, jellyfish and corals. As a group these account for the largest number of envenomations by marine animals. The venom contains various peptides, phospholipase, proteolytic enzymes, haemolytic enzymes, ammonium compounds, serotonin, and other compounds that together are highly antigenic. Effects range from severe burning pain with localised skin erythema, through mild systemic upset, to severe systemic reactions involving vomiting, chest pain, convulsions, and respiratory failure. Extremely toxic species such as the box jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri) and Irukandji (Carukia barnesi) are found in tropical Australian and Indo‐Pacific waters.

Stings

Several species of marine animals cause a ‘sting' by puncturing the victim's skin with a specialised apparatus and introducing venom into the puncture wound. This group includes sea urchins, cone shells, starfish, stingrays, catfish, Weever fish, and a family of fish known as Scorpaenidae. The Scorpaenidae envenomate by erecting spines on their dorsal, anal, and pelvic fins able to pierce skin and introduce venom. Those found in tropical and temperate waters include lionfish (Pterois), scorpion fish (Scorpaena) and the lethal stonefish (Synanceja). Envenomation produces severe localised pain, swelling, and often tissue necrosis. Systemic symptoms may be mild or severe with cardiorespiratory collapse in the case of the stonefish. Weever fish are found off the coast of UK and cause severe pain but less severe systemic symptoms.

Bites

Species that envenomate by biting include octopi and sea snakes. The blue ringed octopus has caused several fatalities. Its venom, introduced from salivary glands close to the animal's beak, is a vasodilator and potent neurotoxin. All fatalities have occurred on handling the animal out of the water and there is no available antivenom. It is found in Australian and Indo‐Pacific waters. Sea snakes are found commonly in the tropical and warm temperate parts of the Pacific and Indian oceans. Neurotoxic venom is introduced through the victim's skin by two to four maxillary fangs. The bite may be painless, but systemic symptoms often occur within two to eight hours. These include myalgia and ascending paralysis, and rarely death. There is no specific antivenom, but symptoms may respond to multivalent snake antivenom. Rarely, envenomations will lead to severe systemic symptoms including cardiovascular or neurological system failure.

Appendix 2 Levels of evidence

Ia: evidence from meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials

Ib: evidence from at least one randomised controlled trial

IIa: evidence from at least one controlled study without randomisation

IIb: evidence from at least one other type of quasi‐experimental study

III: evidence from non‐experimental descriptive studies, such as comparative studies, correlation studies and case–control studies

IV: evidence from expert committee reports or opinions and/or clinical experience of respected authorities

(Adapted from the US Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Classification. Clinical Practice Guidelines No. 1: acute pain management: operative or medical procedure and trauma. Rockville MD, US Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none declared

References

- 1.Fitzgerald F T. Animal bites and stings. In: Humes HD, ed. Kelly's Textbook of Internal Medicine. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000

- 2.Auerbach P S. Trauma and envenomations from marine fauna. In: Tintinalli JE, Kelen GD, Stapczynski JS, eds. Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 5th edn. New York: American College of Emergency Physicians, 19991256–1261.

- 3.Trestrail III J H, Al‐Mahasneh Q M. Lionfish string experiences of an inland poison center: A retrospective study of 23 cases. Vet Hum Toxicol 198931173–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kizer K W, McKinney H E. Auerbach PS. Scorpaenidae envenomation. A five‐year poison center experience. JAMA 1985253807–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Auerbach P S. Marine envenomations. N Engl J Med 1991325486–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russell F. Studies on the mechanism of death from stingray venom: A report of two fatal cases. Am J Med Sci 1958235566–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russell F E. Weever fish sting: the last word. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983287981–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas C S, Scott S A, Galanis D J.et al Box jellyfish (Carybdea alata) in Waikiki: their influx cycle plus the analgesic effect of hot and cold packs on their stings to swimmers at the beach: a randomized, placebo‐controlled, clinical trial. Hawaii Med J 200160100–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nomura J T, Sato R L, Ahern R M.et al Yamamoto LG. A randomized paired comparison trial of cutaneous treatments for acute jellyfish (Carybdea alata) stings. Am J Emerg Med 200220624–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loten C, Scokes B, Worsley D.et al A randomised controlled trial of hot water (45°C) immersion versus ice packs for pain relief in blue bottle stings. Med J Aust 2006184329–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowra J, Gillet M, Morgan J.et al A trial comparing hot showers and icepack in the treatment of physalia envenomation [abstract]. Emerg Med 200214A22 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshimoto C M, Yanagihara A A. Cnidarian (coelenterate) envenomations in Hawaii improve following heat application. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hygiene 200296300–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isbister G K. Venomous fish stings in tropical northern Australia. Am J Emerg Med 200119561–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Briars G L, Gordon G S. Envenomation by the lesser weever fish. Br J Gen Pract 199242213. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halpern P, Sorkine P, Raskin Y. Envenomation by Trachinus draco in the eastern Mediterranean. Eur J Emerg Med 20029274–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fenner P. Marine bites and stings first aid and medical treatment. Med Today 2002326–31. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fenner P. Marine envenomation: An update. A presentation on the current status of marine envenomation first aid and medical treatments. Emerg Med 200012295–302. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawdon G M, Winkel K D. Venomous marine creatures. Aust Fam Physician 1997261369–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer P K. Stingray injuries. Wilderness Environ Med 1997824–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weever fish sting [comment] Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983;287:559. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.British Medical Association and the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain British National Formulary. BNF No. 44/Emergency treatment of poisoning/Other poisons/Snake bites and animal stings/Marine stings. Available at: www.bnf.org/bnf/bnf/current/doc/29569.htm (accessed 15 December 2005)

- 22.Toxbase (Poisons information) Weeverfish/lionfish etc. Available at: www.spib.axl.co.uk/Toxbaseindex.htm (accessed 15 December 2005)

- 23.International Life Saving Federation Medical statement on marine envenomation. Available at: www.ilsf.org/medical/policy_06.htm (accessed 15 December 2005)

- 24.Pacy M. Bullrout stings. Aust Fam Physician 199827344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pacy H. Catfish and stingrays: hot water is first aid. Aust Fam Physician 199827343–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patten B M. Letter: More on catfish stings. JAMA 1975232248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilmshurst P. Stone fish bite. BMJ 1990300463–464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lalwani K. Animal toxins: Scorpaenidae and stingrays. BJA: Br J Anaesth 199575247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hawden G. Venomous marine creatures: Reply. Aust Fam Physician 199827344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoshimoto C M. Hot‐water immersion for treatment of fish stings. Am Fam Physician 199552779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gordon D J, Millar R. Stone fish bite. BMJ 1990300463–464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bush S P. Anesthesia for fish envenomation. Ann Emerg Med 199729692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horton A. Beware of the Weever fish! British Marine Life Study Society. Available at: www.glaucus.org.uk/weever2.htm (accessed 15 December 2005)

- 34.University of Sydney Marine envenomations. Available at: www.usyd.edu.au/anaes/venom/marine_enven.html (accessed 15 December 2005)

- 35.University of Melbourne First aid and medical treatment for Australian venomous marine bites and stings. Available at: www.google.com/search?q = cache:4nmANL1ajA4J : www.avru.unimelb.edu.au/avruweb/marinea.htm (accessed 15 Junuary 2005)

- 36.Australian Resuscitation Council Policy 8.9.8. Envenomation – fish stings March 2001. Available at: www.resus.org.au ; link guidelines; link guideline 8.9.8‐fish stings (accessed 15 December 2005)

- 37.Australian Resuscitation Council Guideline 8.9.6. Envenomation – jellyfish stings Feb 2005. Available at: www.resus.org.au ; link guidelines; link guideline 8.9.6‐Jellyfish stings (accessed 15 December 2005)

- 38.Muirhead D. Applying pain theory in fish spine envenomation. South Pacific Underwater Med Soc J 200232150–153. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carrette T J, Cullen P, Little M.et al Temperature effects on box jellyfish venom: a possible treatment for envenomed patients? Med J Aust 2002177654–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davies R S, Evans R J. Weever fish stings: a report of two cases presenting to an accident and emergency department. J Accid Emerg Med 199613139–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perkins R, Morgan S. Poisoning, envenomation, and trauma from marine creatures. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69: 885–90, 893–4, [PubMed]