Abstract

Context: Obesity is characterized by reduced GH secretion, but data regarding IGF-I levels and their determinants are conflicting.

Objectives: The objectives were to determine whether IGF-I levels are reduced and to investigate determinants of GH and IGF-I in healthy overweight and obese women.

Design: A cross-sectional study was performed.

Setting: The study was conducted at a General Clinical Research Center.

Study Participants: Thirty-four healthy women without pituitary/hypothalamic disease participated, including 11 lean [body mass index (BMI) <25 kg/m2], 12 overweight (BMI ≥25 kg/m2 and <30 kg/m2), and 11 obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) women of comparable age (overall mean age, 30.7 ± 7.8 yr).

Intervention: There was no intervention.

Main Outcome Measures: The main outcome measures were frequent sampling (every 10 min for 24 h) for GH, peak GH after GHRH-arginine stimulation, IGF-I, IGF binding protein-3, estrone, estradiol, testosterone, free testosterone, SHBG, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance, and abdominal fat.

Results: Mean 24-h GH and peak stimulated GH were lower in overweight than lean women and lowest in obese women. Mean IGF-I levels trended lower in obese, but not overweight, compared with lean women. Free testosterone was positively associated with IGF-I (R = 0.36, P = 0.04) but not with GH measures. Visceral fat was the only determinant of mean 24-h GH (R2 = 0.66, P < 0.0001) and of peak stimulated GH (R2 = 0.63, P < 0.0001), and mean 24-h GH accounted for 39% of the variability of IGF-I (P = 0.0002), with an additional 28% (P < 0.0001) attributable to free testosterone levels.

Conclusions: Despite a linear decrease in GH secretion and peak stimulated GH levels with increasing BMI in healthy overweight and obese women, IGF-I levels were not commensurately reduced. Androgens may contribute to this relative preservation of IGF-I secretion in overweight and obese women despite reduced GH secretion.

Despite a linear decrease in GH secretion and peak stimulated GH levels with increasing body mass index in healthy overweight and obese women, IGF-I levels are not commensurately reduced. Androgens may contribute to this relative preservation of IGF-I secretion despite reduced GH secretion.

Although it is established that obesity is characterized by reduced GH secretion, data regarding IGF-I levels and their determinants in obesity are conflicting. Although some studies have demonstrated a degree of reduction in IGF-I levels commensurate with the known reduction in endogenous GH secretion (1,2,3,4,5,6), others report only slightly low IGF-I levels despite marked reductions in GH secretion (7). Still other studies report normal (8,9) or high IGF-I levels (10,11). Studies investigating the effects of body composition on suppression of GH levels in obese men and women have established that visceral adipose tissue mass is a strong determinant of GH (12,13,14) and is also a predictor of IGF-I levels (4,15). We therefore measured GH (mean 24-h, as measured by every 10 min sampling, and peak after stimulation with GHRH and arginine) and IGF-I levels in overweight and obese women and compared them with those of lean female controls to determine whether IGF-I levels are reduced in such women.

Because GH receptor activation is the primary determinant of IGF-I levels, the underlying mechanisms for the dissociation between GH and IGF-I levels in this group of women are not clear, and we therefore investigated whether body composition, estrogens, androgens, and/or elevated IGF binding protein (IGFBP)-3 levels predict GH or IGF-I levels. There are few published studies that have investigated gonadal steroids, either estrogens or androgens, as potential determinants of GH and IGF-I. In addition, although androgens are known to stimulate the GH-IGF-I axis in men (16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23), little is known about their effects in women with low GH secretion, either hypopituitary or obese. Relative hyperestrogenemia or hyperandrogenemia in overweight and obese women might be expected to stimulate GH secretion, and are therefore unlikely to be primary determinants of the reduced GH secretion observed in these groups of women. However, when we found that endogenous IGF-I secretion was relatively preserved compared with GH secretion in our group of obese and overweight women, we hypothesized that because testosterone augments the GH-dependent stimulatory effect on IGF-I production (24), relative hyperandrogenemia might stimulate liver IGF-I production in opposition to diminished GH action in overweight and obese women. This is in contrast to the known effects of estrogens to cause GH resistance in the liver, resulting in a relative reduction of IGF-I production per unit of GH secretion (25,26,27,28). We therefore investigated putative determinants of GH and IGF-I levels to characterize the effects of androgens in comparison to other known determinants, including estrogens body composition parameters and insulin resistance, on GH and IGF-I secretion in healthy young overweight and obese women.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

We studied 34 healthy volunteers recruited from the community through advertisements. To participate in the study, volunteers were required to be eumenorrheic and to have serum testosterone levels in the normal female range. Exclusion criteria included hypothalamic or pituitary disorders, diabetes mellitus or other chronic illnesses, estrogen or glucocorticoid use, and weight greater than 280 pounds [due to the limitations of the dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry and computed tomography (CT) scanners].

Materials and methods

The study was approved by the Partners Healthcare Inc. Institutional Review Board, and written informed consent was obtained from each study participant.

Each participant was admitted to the General Clinical Research Center at the Massachusetts General Hospital, where serum was collected every 10 min for 24 h starting at 0800 h during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. During this admission to the General Clinical Research Center, vigorous activity, including exercise, was prohibited. Fasting blood was obtained for IGF-I, IGFBP-3, estrone, estradiol, testosterone, and SHBG. A fasting GHRH-arginine stimulation test was performed as follows. GHRH (1 μg/kg) plus arginine (0.5 g/kg; maximum, 30 g) was administered iv, and GH levels were drawn at baseline and every 30 min for 2 h. This test has been validated in comparison to the gold standard insulin tolerance test, with proposed cut-offs for the diagnosis of GH deficiency of 4.1 to 9 ng/ml (29,30). Baseline clinical characteristics, GHRH-arginine stimulation test results, IGF-I, waist circumference, and fasting insulin and glucose levels in these study subjects were included in a previously published manuscript (31).

Body composition measures

Fat and fat-free mass were measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry using a Hologic QDR-4500 densitometer (Hologic Inc., Waltham, MA), with an accuracy error for body fat mass of 1.7% and for fat-free mass of 2.4% (32). Total, sc fat, and visceral abdominal fat compartments were measured in duplicate using single-slice quantitative CT scans at the level of L4 with 10-mm-thick axial images (General Electric RP High Speed Helical CT Scanner, Milwaukee, WI) and graphical analysis software (General Electric Advantage Windows Work Station Version 2.0, General Electric). Technical factors for the scanning were 80 kVp, 70 mA, and 2-sec scan time. Midwaist circumference was measured as the midpoint between the iliac crest and the lowest rib, measured in a horizontal plane parallel to the floor.

Biochemical analyses

Serum samples were collected and stored at −80 C. Serum GH was measured using an immunoradiometric assay (IRMA) kit [Diagnostic Systems Laboratories (DSL), Inc., Webster, TX], with a minimum detection limit of 0.01 ng/ml, an intraassay coefficient of variation (cv) of 3.1–5.4%, and an interassay cv of 5.9–11.5%. Serum IGF-I levels were measured using an Immulite 2000 automated immunoanalyzer [Diagnostic Products Corporation (DPC), Inc., Los Angeles, CA], by a solid-phase enzyme-labeled chemiluminescent immunometric assay, with an interassay cv of 3.7- 4.2%. IGFBP-3 was measured by IRMA kit (DSL, Inc.) with a minimum detection limit of 0.5 ng/ml, an intraassay cv of 1.8–3.9%, and an interassay cv of 0.5–1.9%. Estrone was measured by RIA kit (DSL, Inc.) with a minimum detection limit of 1.2 pg/ml, an intraassay cv of 4.4–9.4%, and interassay cv of 6.0–11.1%. Estradiol was measured by ultrasensitive RIA kit (DSL, Inc.) with a minimum detection limit of 2.2 pg/ml, intraassay cv of 6.5–8.9%, and interassay cv of 7.5–12.2%. Serum testosterone was measured by RIA kit (DPC, Inc.) with a minimum detection limit of 2 ng/dl, an intraassay cv of 4.1–10.5%, and an interassay cv of 5.9–12%. SHBG was measured by IRMA (DPC, Inc.) with a minimum detection limit of 0.5 nmol/liter, an intraassay cv of 2.8–5.3%, and an interassay cv of 7.9–8.5%. Free testosterone was calculated from total testosterone and SHBG by the laws of mass action, which has been validated in comparison to free testosterone by equilibrium dialysis (33). Insulin was measured using a RIA kit (Linco Research, Inc., St. Charles, MO) with a sensitivity of 2 μU/ml, an intraassay cv of 2.2–4.4%, and an interassay cv of 2.9–6.0%. The homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) has been validated as an accurate measurement of insulin resistance and was calculated as [insulin(μIU/ml)∗glucose(mmol/liter)]/22.5 (34).

Statistical analysis

JMP Statistical Discoveries Software (version 4.0.2, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) was used for statistical analyses. All variables were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Means were compared with ANOVA for variables with normal distributions and with the Wilcoxon test for those with non-normal distributions. Corrections for multiple comparisons were made by Tukey-Kramer. Univariate regression models were constructed, and Spearman coefficients are reported. Forward stepwise regression models, with 0.250 for probability to enter and 0.100 for probability to leave, were constructed to determine predictors of 24-h mean GH, peak stimulated GH, and IGF-I levels. The variables entered into the models are delineated in the Results section and were log-transformed before entry into the models if not normally distributed. Linear regressions were controlled for body mass index (BMI) by constructing multivariate least-squares regression models and entering BMI as a covariate into the models. All variables that were not normally distributed were log-transformed before being entered into these regression analyses. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed P value <0.05. Results are expressed as mean ± sem.

Results

Clinical characteristics of study subjects

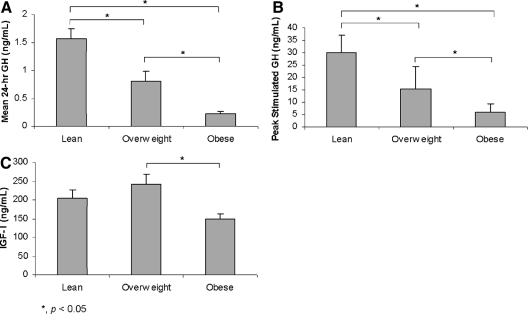

Clinical characteristics, body composition, and endocrine data are shown in Table 1. Study subjects were categorized as lean (n = 11) if less than 25 kg/m2, overweight (n = 12) if at least 25 but less than 30 kg/m2, or obese (n = 11) if 30 kg/m2 or greater, based on World Health Organization definitions (35). The mean age of the three groups was similar. Study participants ranged in age from 19–45 yr and in BMI from 19.2 to 40.6 kg/m2. Mean 24-h GH and mean peak stimulated GH were lower in overweight than lean women and lowest in obese women (Fig. 1). Mean IGF-I was lower in obese than overweight women, and there was a trend toward a lower mean IGF-I level in obese compared with lean women. However, the mean IGF-I level was not reduced in overweight women (Fig. 1). Mean free testosterone levels were higher in overweight and obese than lean women (Table 1). Mean levels of other gonadal steroids and IGFBP-3 were similar among the groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics, body composition, and endocrine data

| All subjects (n = 34) | Lean BMI <25 kg/m2 (n = 11) | Overweight 25 kg/m2 ≤ BMI <30 kg/m2 (n = 12) | Obese BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (n = 11) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 30.7 ± 1.3 | 30.5 ± 2.3 | 28.1 ± 2.5 | 33.8 ± 1.8 |

| Weight (kg) | 77.1 ± 2.9 | 62.6 ± 2.0 | 72.8 ± 1.3a | 96.2 ± 4.7a,b |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.4 ± 1.0 | 22.3 ± 0.6 | 27.6 ± 0.4a | 35.4 ± 0.8a,b |

| Midwaist circumference (cm) | 90.3 ± 2.4 | 77.4 ± 1.5 | 88.5 ± 1.6a | 104.9 ± 3.6a,b |

| Mean 24-h GH (ng/ml) | 0.87 ± 0.13 | 1.57 ± 0.17 | 0.81 ± 0.18a | 0.22 ± 0.05a,b |

| GH stimulation peak (ng/ml) | 17.7 ± 2.1 | 30.0 ± 2.2 | 15.2 ± 2.6a | 6.1 ± 1.1a,b |

| IGF-I (ng/ml) | 201 ± 14 | 204 ± 23 | 243 ± 25 | 150 ± 13b |

| IGF-I z-score | −0.47 ± 0.22 | −0.29 ± 0.41 | 0.05 ± 0.37a | −1.21 ± 0.26b |

| IGFBP-3 (μg/ml) | 3.69 ± 0.09 | 3.63 ± 0.14 | 3.89 ± 0.11 | 3.53 ± 0.22 |

| Total fat mass (kg) | 29.0 ± 2.0 | 17.8 ± 1.3 | 26.7 ± 1.0a | 42.8 ± 2.2a,b |

| Nontrunk fat mass (kg) | 15.9 ± 1.0 | 10.4 ± 0.7 | 14.4 ± 0.6a | 23.1 ± 1.1a,b |

| Fat-free mass (kg) | 48.3 ± 1.3 | 45.9 ± 2.0 | 46.0 ± 1.2 | 53.3 ± 2.6b |

| Abdominal fat cross-sectional area (mm2) | 48,393 ± 4,145 | 24,529 ± 3,484 | 47,789 ± 4,236a | 72,918 ± 4,942a,b |

| Visceral fat cross-sectional area (mm2) | 7,195 ± 831 | 3,484 ± 556 | 6,787 ± 747a | 11,351 ± 1,718a,b |

| Subcutaneous fat cross-sectional area (mm2) | 32,268 ± 2,373 | 19,231 ± 2,047 | 29,522 ± 1,489a | 48,299 ± 2,663a,b |

| Estradiol (pg/ml) | 33.2 ± 2.5 | 31.6 ± 3.1 | 34.1 ± 5.1 | 33.7 ± 5.0 |

| Estrone (pg/ml) | 63.7 ± 5.2 | 50.9 ± 5.1 | 68.3 ± 10.2 | 71.5 ± 10.0 |

| Total testosterone (ng/dl) | 28.8 ± 2.7 | 21.4 ± 2.8 | 31.5 ± 4.8 | 33.3 ± 5.6 |

| SHBG (nmol/liter) | 44.3 ± 3.7 | 55.1 ± 6.7 | 43.3 ± 6.9 | 34.4 ± 4.0a |

| Free testosterone (ng/dl) | 0.48 ± 0.05 | 0.30 ± 0.05 | 0.52 ± 0.07a | 0.63 ± 0.12a |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 83.0 ± 1.8 | 80.5 ± 4.1 | 81.8 ± 1.9 | 87.1 ± 2.9 |

| Fasting insulin (μIU/ml) | 10.1 ± 1.2 | 6.2 ± 0.7 | 10.9 ± 1.8 | 13.2 ± 2.8a |

| HOMA-IR | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.9a |

P < 0.05, compared to lean group (control: BMI <25 kg/m2).

P < 0.05, compared to overweight group (25 kg/m2 ≤ BMI <30 kg/m2).

Figure 1.

Mean 24-h GH (A) and peak stimulated GH (B) were lower in overweight than lean women and lowest in obese women. Mean IGF-I levels (C) were lower in obese than overweight women, and there was a trend toward a lower mean IGF-I level in obese than lean women. There was no difference in mean IGF-I level in the lean and overweight groups.

Determinants of 24-h mean GH, peak stimulated GH, and IGF-I levels

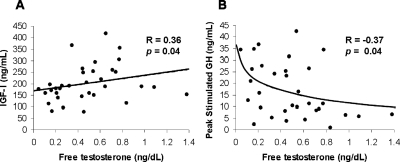

Linear regression models investigating potential body composition and endocrine determinants of 24-h mean GH, peak GH after stimulation with GHRH and arginine, and IGF-I were constructed in the group as a whole (n = 34), and results (correlation coefficients and P values) are shown in Table 2. BMI and all measures of fat mass were strong inverse predictors of mean 24-h GH and peak GH after stimulation. BMI, total fat mass, and visceral adipose tissue were also negative predictors of IGF-I levels. Free testosterone (R = 0.36, P = 0.04) was positively associated with IGF-I (Fig. 2A), and there was a trend toward an association between total testosterone and IGF-I levels (R = 0.30, P = 0.08). After controlling for BMI, the association of total testosterone and IGF-I became significant (P = 0.006). After controlling for BMI, the statistical significance of the association between free testosterone and IGF-I increased (P = 0.002). Free testosterone was inversely associated with peak stimulated GH (R = −0.37, P = 0.04) (Fig. 2B), but this relationship was no longer significant after controlling for BMI. There was a trend toward an inverse association of estrone (R = −0.31, P = 0.09), but not estradiol, with peak stimulated GH levels; the association was no longer evident after controlling for BMI using multivariate regression modeling. Although neither estrone nor estradiol levels correlated with IGF-I levels, after controlling for BMI a positive association between estrone, but not estradiol, and IGF-I became evident (R = 0.33, P = 0.03).

Table 2.

Predictors of GH and IGF-I secretion: univariate analyses

| 24-h Mean GH

|

Peak stimulated GH

|

IGF-I

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | P | R | P | R | P | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | −0.76 | <0.0001 | −0.81 | <0.0001 | −0.36 | 0.04 |

| Midwaist circumference (cm) | −0.73 | <0.0001 | −0.76 | <0.0001 | −0.25 | 0.16 |

| Total fat mass (kg) | −0.80 | <0.0001 | −0.80 | <0.0001 | −0.38 | 0.03 |

| Nontrunk fat mass (kg) | −0.75 | <0.0001 | −0.72 | <0.0001 | −0.39 | 0.02 |

| Fat-free mass (kg) | −0.18 | 0.30 | −0.37 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.87 |

| Abdominal fat cross-sectional area (mm2) | −0.70 | <0.0001 | −0.76 | <0.0001 | −0.29 | 0.10 |

| Visceral adipose tissue (mm2) | −0.84 | <0.0001 | −0.75 | <0.0001 | −0.40 | 0.02 |

| Subcutaneous abdominal fat (mm2) | −0.72 | <0.0001 | −0.72 | <0.0001 | 0.24 | 0.16 |

| IGFBP-3 (μg/ml) | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.34 | 0.50 | 0.002 |

| Estradiol (pg/ml) | 0.15 | 0.40 | −0.13 | 0.49 | 0.11 | 0.55 |

| Estrone (pg/ml) | −0.11 | 0.52 | −0.31 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.31 |

| Total testosterone (ng/dl) | −0.06 | 0.73 | −0.22 | 0.24 | 0.30 | 0.08 |

| Free testosterone (ng/dl) | −0.21 | 0.23 | −0.37 | 0.04 | 0.36 | 0.04 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | −0.24 | 0.19 | −0.19 | 0.31 | −0.40 | 0.02 |

| Fasting insulin (μIU/ml) | −0.39 | 0.03 | −0.52 | 0.003 | −0.03 | 0.85 |

| HOMA-IR | −0.39 | 0.03 | −0.52 | 0.004 | −0.05 | 0.78 |

Figure 2.

Free testosterone levels positively predicted IGF-I levels (R = 0.36, P = 0.04) (A) and inversely predicted peak stimulated GH levels (R = −0.37, P = 0.04) (B). After controlling for BMI using standard least squares multivariate regression modeling, the positive association between free testosterone and IGF-I achieved greater statistical significance (P = 0.002), and the association of free testosterone with peak stimulated GH levels was no longer evident. Spearman coefficients are reported. Lines were fitted to the data, which were log-transformed if not normally distributed.

Visceral fat, free testosterone, HOMA-IR, and estrone were entered into stepwise regression models for peak stimulated GH and 24-h mean GH. Visceral fat was the only signficant determinant of peak GH, determining 63% of the variability (R2 = 0.63, P < 0.0001), and of 24-h mean GH (R2 = 0.66, P < 0.0001), determining 66% of the variability. Mean 24-h GH, visceral fat, free testosterone, HOMA-IR, and estrone levels were entered in the stepwise regression model constructed to investigate the determinants of IGF-I levels. The 24-h mean GH accounted for 39% of the variability of IGF-I levels (R2 = 0.39, P = 0.0002), with an additional 28% (cumulative R2 = 0.67, P < 0.0001) attributable to free testosterone levels. When age also was entered into the model, age accounted for 41% of the variability (P = 0.0001), mean 24-h GH accounted for an additional 10% of the variability (cumulative R2 = 0.51, P = 0.021), and an additional 14% of the variability in IGF-I levels was attributable to free testosterone levels (cumulative R2 = 0.65, P = 0.003).

Predictors of gonadal steroid and binding protein levels

Predictors of gonadal steroid levels are shown in Table 3. Estrone was positively associated with BMI (R = 0.35, P = 0.04), total abdominal fat (R = 0.38, P = 0.03), and sc abdominal fat (R = 0.41, P = 0.02). Free testosterone was positively associated with BMI (R = 0.36, P = 0.04), as well as with total abdominal fat (R = 0.38, P = 0.03), visceral adipose tissue (R = 0.36, P = 0.04), sc abdominal fat (R = 0.36, P = 0.04), and fat-free mass (R = 0.35, P = 0.04). Neither estradiol, total testosterone, nor IGFBP-3 levels were associated with BMI or any body composition measures.

Table 3.

Predictors of gonadal steroid levels: univariate analyses

| Estradiol

|

Estrone

|

Total testosterone

|

Free testosterone

|

IGFBP-3

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | P | R | P | R | P | R | P | R | P | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.09 | 0.61 | 0.35 | 0.04 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.36 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.92 |

| Total fat mass (kg) | 0.08 | 0.66 | 0.31 | 0.07 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.08 | −0.08 | 0.67 |

| Abdominal fat cross-sectional area (mm2) | 0.14 | 0.44 | 0.38 | 0.03 | 0.28 | 0.11 | 0.38 | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.76 |

| Visceral adipose tissue (mm2) | −0.04 | 0.83 | 0.27 | 0.11 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.74 |

| Subcutaneous abdominal fat (mm2) | 0.14 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.36 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.77 |

| Fat-free mass (kg) | 0.24 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.86 |

| HOMA-IR | 0.15 | 0.42 | 0.30 | 0.10 | 0.40 | 0.02 | 0.55 | 0.001 | 0.18 | 0.33 |

Discussion

Our data demonstrate that despite a linear decrease in GH secretion and peak stimulated GH levels with increasing BMI, IGF-I levels are not reduced in overweight women and are not reduced to the same degree as GH secretion in obese eumenorrheic women. We also demonstrate that androgens may contribute to the relative preservation of IGF-I secretion in viscerally obese women despite reduced GH secretion. Consistent with data from other groups, we also show that visceral adiposity is a strong determinant of decreased GH secretion in obese women and a significant, though less important, determinant of IGF-I levels.

IGF-I levels have been variably shown to be low (1,2,3,4,5,6), normal (8,9), or high (10,11) in overweight and obese women. Although IGF-I has been shown in one study to increase in concert with GH secretion after gastric bypass (36), in two other studies, mean IGF-I levels failed to increase despite increases in mean stimulated GH after a significant reduction in BMI (37,38). In addition, data from two studies suggest that the relationship between BMI and IGF-I levels may be nonlinear, following an inverse “U” shape, with a peak at a BMI of about 25 kg/m2 (9,39). Our data suggest that although IGF-I levels may be modestly reduced in women with obesity, they are normal in overweight women. Because GH stimulation is thought to be the primary determinant of IGF-I levels, the underlying mechanisms for the dissociation between GH and IGF-I levels in this group of women are not clear, and we therefore investigated whether body composition, estrogens, androgens, insulin resistance, or elevated IGFBP-3 levels predict GH or IGF-I levels.

The effects of androgens on GH secretion and IGF-I levels have been studied in men, but little is known about the relationship between androgens and the GH-IGF-I axis in women. In men, evidence from studies using several different physiological models demonstrates that testosterone stimulates GH release, thereby contributing to an increase in IGF-I levels. In hypogonadal men, GH levels are decreased, and restoration of testosterone levels, with androgen replacement or pulsatile GnRH therapy, results in normalization of GH (16,17,18,19); testosterone replacement also increases IGF-I secretion in hypogonadal men (16,18,19). Similarly, administration of testosterone to prepubertal and peripubertal boys (20,21,22), as well as elderly men (23), increases endogenous GH and IGF-I secretion. In addition, and of note, there is evidence of a direct, independent effect of testosterone to stimulate IGF-I levels in men, as shown by Gibney et al. (24) who investigated the effects on IGF-I of testosterone administration alone, GH alone, or the combination to 12 hypopituitary men. Although testosterone administration alone did not increase IGF-I, the combination of GH plus testosterone increased IGF-I more than GH alone, suggesting that testosterone exerts an independent effect to increase IGF-I in the presence, but not absence, of GH in men. As expected, free testosterone levels in our study negatively correlated with stimulated GH levels, the former increasing and the latter decreasing with weight. Also, as predicted, after controlling for BMI, no independent association of GH, either 24-h or peak stimulated, could be detected. However, an interesting finding was that free testosterone levels positively predicted IGF-I levels and that the level of significance of this relationship increased after controlling for the effects of BMI. In addition, in stepwise regression models that included HOMA-IR, a validated measure of insulin resistance, free testosterone was chosen by the model over HOMA-IR as a significant predictor of IGF-I levels. These data suggest a direct stimulatory effect of testosterone on IGF-I production. Although the degree of hyperandrogenemia was similar in overweight and obese women, GH levels (both mean 24-h and peak stimulated) were lower in obese than overweight women. This combination of effects may at least partially explain our finding of normal mean IGF-I levels in overweight women and a lower mean IGF-I level in obese women, but a mean IGF-I that was relatively higher than would be predicted from decreased GH stimulation alone.

To our knowledge, we are the first to report evidence of a possible dissociation of the effects of testosterone on hypothalamic vs. pituitary function in the GH-IGF-I axis in women. Data exploring the relationship between GH and androgens in obese women have not been published. In contrast, there is a small literature on androgens as determinants of IGF-I levels in women without organic hypothalamic or pituitary disease. Our data investigating determinants of IGF-I are consistent with three reports of associations of androgen and androgen precursors with IGF-I levels, including dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (7,40,41), testosterone, and androstenedione (7), in healthy women. Androstenedione is the most prevalent, although not most potent, circulating androgen in women, and it is a precursor to both testosterone and estrone. Further investigation into the role of androstenedione as a moderator of the GH-IGF-I axis is merited. Morevoer, additional studies investigating the effects of androgens on hepatic IGF-I production in women are warranted to determine whether our data suggesting that relative hyperandrogenemia in overweight and obese women may be one mechanism underlying a relative preservation of endogenous IGF-I despite reduced GH secretion in this population.

In contrast to our data suggesting that androgen levels may influence IGF-I levels in overweight and obese women, our data do not suggest an important role for estrogens as determinants of GH or IGF-I secretion in healthy obese and overweight women. Our data are consistent with data from Maccario et al. (7) of 234 healthy women in which androgens were positively associated with IGF-I levels in contrast to estradiol levels, which were not; estrone levels were not assessed, nor was GH secretion. Studies in healthy women have suggested a stimulatory role for endogenous estradiol on GH secretion as supported by periovulatory increases in GH secretion associated with the rise in estradiol and higher GH levels in pre- than postmenopausal women (42,43). Oral estrogens induce a state of GH resistance at the level of the liver, resulting in decreased IGF-I levels despite increased GH secretion (43,44,45). In addition, it has been demonstrated that women have lower levels of IGF-I for comparable endogenous GH levels than their male counterparts or a relative GH resistance state compared with men. This has been shown in healthy women as well as women with GH deficiency and those with acromegaly, and it has been attributed to the effects of estrogens (25,26,27). In contrast, our data do not support an important role for estrogens in the determination of the variability GH or IGF-I levels among lean, overweight and obese otherwise healthy women of reproductive age.

Similarly, our data do not support dysregulation of IGFBP-3 levels as a mechanism underlying the relatively high IGF-I levels in overweight and obese women. If IGFBP-3, the most ubiquitous IGF-I binding protein (46,47,48), were elevated in overweight and obese women, a relative preservation of total IGF-I levels could belie depressed free IGF-I levels. Our data do not suggest this to be the case because IGFBP-3 levels were not increased in overweight or obese women and were not positively associated with BMI, consistent with published data from other groups (9,11). Our data reporting normal IGFBP-3 levels in overweight and obese women suggest that the relative sparing of IGF-I levels likely reflects biological activity. However, measurement of IGF-I action using a bioassay would be an important next step to investigate this hypothesis further. In addition, Roelen et al. (49) have demonstrated a strong positive correlation between visceral adipose tissue and GH binding protein, such that, in general, those men and women with more visceral adiposity had higher levels of circulating GH binding protein levels. Therefore, a reduction in GH binding protein is not a likely cause of low total GH levels. Instead, low total GH levels in obesity likely do reflect low free GH levels, and the reasons for the lack of a commensurate decrease in IGF-I levels are not evident.

Our data confirm reports from other groups of the importance of body fat, particularly visceral stores of abdominal fat, as determinants of GH (50,51,52) and, less so, IGF-I (15) levels in obese healthy women. We also previously have demonstrated truncal fat to be an important determinant of GH levels in healthy overweight women (53), and a number of studies have demonstrated that visceral adipose tissue is an important determinant of GH secretion in healthy lean men and women (12,13,14). Therefore, our data are consistent with these studies in that they demonstrate that body fat, particularly visceral fat mass, is a strong predictor of GH and a predictor, although a less important one, of IGF-I secretion in healthy women.

In summary, our data suggest that despite a linear decrease in GH secretion with increasing BMI in young women of reproductive age, IGF-I levels are relatively preserved. Our data also suggest that relative hyperandrogenemia in such women may be one mechanism underlying the maintenance of relatively higher IGF-I levels than would be expected based solely on the degree of GH stimulation. Estrogen levels were not important determinants of the variability in GH or IGF-I levels in the group of women studied. Our data are also consistent with published results that have established that body fat, particularly visceral adipose stores, are important inverse determinants of GH levels in young women and significant, though weaker, predictors of IGF-I levels. Further studies are warranted to investigate the effects of androgens on the GH-IGF-I axis in women.

Acknowledgments

We thank the nurses and bionutritionists of the Massachusetts General Hospital General Clinical Research Center and the study subjects who participated in the study.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1 HL077674 and MO1 RR01066.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have no conflicts to declare.

First Published Online July 22, 2008

Abbreviations: BMI, Body mass index; CT, computed tomography; cv, coefficient of variation; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; IGFBP, IGF binding protein; IRMA, immunoradiometric assay.

References

- Copeland KC, Colletti RB, Devlin JT, McAuliffe TL 1990 The relationship between insulin-like growth factor-I, adiposity, and aging. Metabolism 39: 584–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen MH, Hvidberg A, Juul A, Main KM, Gotfredsen A, Skakkebaek NE, Hilsted J, Skakkebae NE 1995 Massive weight loss restores 24-hour growth hormone release profiles and serum insulin-like growth factor-I levels in obese subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 80:1407–1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto H, Kato Y 1993 Relationship between plasma insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) levels and body mass index (BMI) in adults. Endocr J 40:41–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin P, Kvist H, Lindstedt G, Sjostrom L, Bjorntorp P 1993 Low concentrations of insulin-like growth factor-I in abdominal obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 17:83–89 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen MH, Juul A, Hilsted J 2007 Effect of weight loss on free insulin-like growth factor-I in obese women with hyposomatotropism. Obesity (Silver Spring) 15:879–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gram IT, Norat T, Rinaldi S, Dossus L, Lukanova A, Tehard B, Clavel-Chapelon F, van Gils CH, van Noord PA, Peeters PH, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Nagel G, Linseisen J, Lahmann PH, Boeing H, Palli D, Sacerdote C, Panico S, Tumino R, Sieri S, Dorronsoro M, Quiros JR, Navarro CA, Barricarte A, Tormo MJ, Gonzalez CA, Overvad K, Paaske Johnsen S, Olsen A, Tjonneland A, Travis R, Allen N, Bingham S, Khaw KT, Stattin P, Trichopoulou A, Kalapothaki V, Psaltopoulou T, Casagrande C, Riboli E, Kaaks R 2006 Body mass index, waist circumference and waist-hip ratio and serum levels of IGF-I and IGFBP-3 in European women. Int J Obes (Lond) 30:1623–1631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccario M, Ramunni J, Oleandri SE, Procopio M, Grottoli S, Rossetto R, Savio P, Aimaretti G, Camanni F, Ghigo E 1999 Relationships between IGF-I and age, gender, body mass, fat distribution, metabolic and hormonal variables in obese patients. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 23:612–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caufriez A, Golstein J, Lebrun P, Herchuelz A, Furlanetto R, Copinschi G 1984 Relations between immunoreactive somatomedin C, insulin and T3 patterns during fasting in obese subjects. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 20:65–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukanova A, Lundin E, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Muti P, Mure A, Rinaldi S, Dossus L, Micheli A, Arslan A, Lenner P, Shore RE, Krogh V, Koenig KL, Riboli E, Berrino F, Hallmans G, Stattin P, Toniolo P, Kaaks R 2004 Body mass index, circulating levels of sex-steroid hormones, IGF-I and IGF-binding protein-3: a cross-sectional study in healthy women. Eur J Endocrinol 150:161–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg Z, Hertz P, Colin V, Ish-Shalom S, Yeshurun D, Youdim MB, Amit T 1992 The distal axis of growth hormone (GH) in nutritional disorders: GH-binding protein, insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I), and IGF-I receptors in obesity and anorexia nervosa. Metabolism 41:106–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam SY, Lee EJ, Kim KR, Cha BS, Song YD, Lim SK, Lee HC, Huh KB 1997 Effect of obesity on total and free insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1, and their relationship to IGF-binding protein (BP)-1, IGFBP-2, IGFBP-3, insulin, and growth hormone. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 21:355–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clasey JL, Weltman A, Patrie J, Weltman JY, Pezzoli S, Bouchard C, Thorner MO, Hartman ML 2001 Abdominal visceral fat and fasting insulin are important predictors of 24-hour GH release independent of age, gender, and other physiological factors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:3845–3852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahl N, Jorgensen JO, Jurik AG, Christiansen JS 1996 Abdominal adiposity and physical fitness are major determinants of the age-associated decline in stimulated GH secretion in healthy adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81:2209–2215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahl N, Jorgensen JO, Skjaerbaek C, Veldhuis JD, Orskov H, Christiansen JS 1997 Abdominal adiposity rather than age and sex predicts mass and regularity of GH secretion in healthy adults. Am J Physiol 272:E1108–E1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen MH, Frystyk J, Andersen T, Breum L, Christiansen JS, Hilsted J 1994 The impact of obesity, fat distribution, and energy restriction on insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), IGF-binding protein-3, insulin, and growth hormone. Metabolism 43:315–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondanelli M, Ambrosio MR, Margutti A, Franceschetti P, Zatelli MC, degli Uberti EC 2003 Activation of the somatotropic axis by testosterone in adult men: evidence for a role of hypothalamic growth hormone-releasing hormone. Neuroendocrinology 77:380–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giusti M, Torre R, Cavagnaro P, Attanasio R, Traverso L, Giordano G 1989 The effect of long-term pulsatile GnRH administration on the 24-hour integrated concentration of GH in hypogonadotropic hypogonadic patients. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 120:724–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Merriam GR, Sherins RJ 1987 Chronic sex steroid exposure increases mean plasma growth hormone concentration and pulse amplitude in men with isolated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 64:651–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissberger AJ, Ho KK 1993 Activation of the somatotropic axis by testosterone in adult males: evidence for the role of aromatization. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 76:1407–1412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giustina A, Scalvini T, Tassi C, Desenzani P, Poiesi C, Wehrenberg WB, Rogol AD, Veldhuis JD 1997 Maturation of the regulation of growth hormone secretion in young males with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism pharmacologically exposed to progressive increments in serum testosterone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82:1210–1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan BS, Richards GE, Ponder SW, Dallas JS, Nagamani M, Smith ER 1993 Androgen-stimulated pubertal growth: the effects of testosterone and dihydrotestosterone on growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-I in the treatment of short stature and delayed puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 76:996–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loche S, Colao A, Cappa M, Bellone J, Aimaretti G, Farello G, Faedda A, Lombardi G, Deghenghi R, Ghigo E 1997 The growth hormone response to hexarelin in children: reproducibility and effect of sex steroids. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82:861–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis JD, Keenan DM, Mielke K, Miles JM, Bowers CY 2005 Testosterone supplementation in healthy older men drives GH and IGF-I secretion without potentiating peptidyl secretagogue efficacy. Eur J Endocrinol 153:577–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibney J, Wolthers T, Johannsson G, Umpleby AM, Ho KK 2005 Growth hormone and testosterone interact positively to enhance protein and energy metabolism in hypopituitary men. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 289:E266–E271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landin-Wilhelmsen K, Lundberg PA, Lappas G, Wilhelmsen L 2004 Insulin-like growth factor I levels in healthy adults. Horm Res 62(Suppl 1):8–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson C, Ryder WD, Trainer PJ 2001 The relationship between serum GH and serum IGF-I in acromegaly is gender-specific. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:5240–5244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Span JP, Pieters GF, Sweep CG, Hermus AR, Smals AG 2000 Gender difference in insulin-like growth factor I response to growth hormone (GH) treatment in GH-deficient adults: role of sex hormone replacement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85:1121–1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman P, Johansson AG, Siegbahn A, Vessby B, Karlsson FA 1997 Growth hormone (GH)-deficient men are more responsive to GH replacement therapy than women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82:550–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biller BM, Samuels MH, Zagar A, Cook DM, Arafah BM, Bonert V, Stavrou S, Kleinberg DL, Chipman JJ, Hartman ML 2002 Sensitivity and specificity of six tests for the diagnosis of adult GH deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:2067–2079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aimaretti G, Corneli G, Razzore P, Bellone S, Baffoni C, Arvat E, Camanni F, Ghigo E 1998 Comparison between insulin-induced hypoglycemia and growth hormone (GH)-releasing hormone + arginine as provocative tests for the diagnosis of GH deficiency in adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:1615–1618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utz A, Yamamoto A, Hemphill L, Miller KK 2008 Growth hormone deficiency by GHRH/arginine testing criteria predicts increased cardiovascular risk markers in normal young overweight and obese women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:2507–2514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutkia P, Canavan B, Breu J, Torriani M, Kissko J, Grinspoon S 2004 Growth hormone-releasing hormone in HIV-infected men with lipodystrophy. JAMA 292:210–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KK, Rosner W, Lee H, Hier J, Sesmilo G, Schoenfeld D, Neubauer G, Klibanski A 2004 Measurement of free testosterone in normal women and women with androgen deficiency: comparison of methods. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:525–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC 1985 Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and β-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28:412–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2000 Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 894:i-xii. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1–253 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eden Engstrom B, Burman P, Holdstock C, Ohrvall M, Sundbom M, Karlsson FA 2006 Effects of gastric bypass on the GH/IGF-I axis in severe obesity—and a comparison with GH deficiency. Eur J Endocrinol 154:53–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valera Mora ME, Manco M, Capristo E, Guidone C, Iaconelli A, Gniuli D, Rosa G, Calvani M, Mingrone G 2007 Growth hormone and ghrelin secretion in severely obese women before and after bariatric surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring) 15:2012–2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Marinis L, Bianchi A, Mancini A, Gentilella R, Perrelli M, Giampietro A, Porcelli T, Tilaro L, Fusco A, Valle D, Tacchino RM 2004 Growth hormone secretion and leptin in morbid obesity before and after biliopancreatic diversion: relationships with insulin and body composition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:174–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukanova A, Soderberg S, Stattin P, Palmqvist R, Lundin E, Biessy C, Rinaldi S, Riboli E, Hallmans G, Kaaks R 2002 Nonlinear relationship of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I and IGF-I/IGF-binding protein-3 ratio with indices of adiposity and plasma insulin concentrations (Sweden). Cancer Causes Control 13:509–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bednarek-Tupikowska G, Tworowska-Bardzinska U, Tupikowski K, Bohdanowicz-Pawlak A, Szymczak J, Kubicka E, Skoczynska A, Milewicz A 2008 The correlations between endogenous dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate and some atherosclerosis risk factors in premenopausal women. Med Sci Monit 14:CR37–CR41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccario M, Mazza E, Ramunni J, Oleandri SE, Savio P, Grottoli S, Rossetto R, Procopio M, Gauna C, Ghigo E 1999 Relationships between dehydroepiandrosterone-sulphate and anthropometric, metabolic and hormonal variables in a large cohort of obese women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 50:595–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovesen P, Vahl N, Fisker S, Veldhuis JD, Christiansen JS, Jorgensen JO 1998 Increased pulsatile, but not basal, growth hormone secretion rates and plasma insulin-like growth factor I levels during the periovulatory interval in normal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:1662–1667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissberger AJ, Ho KK, Lazarus L 1991 Contrasting effects of oral and transdermal routes of estrogen replacement therapy on 24-hour growth hormone (GH) secretion, insulin-like growth factor I, and GH-binding protein in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 72:374–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellantoni MF, Vittone J, Campfield AT, Bass KM, Harman SM, Blackman MR 1996 Effects of oral versus transdermal estrogen on the growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor I axis in younger and older postmenopausal women: a clinical research center study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81:2848–2853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friend KE, Hartman ML, Pezzoli SS, Clasey JL, Thorner MO 1996 Both oral and transdermal estrogen increase growth hormone release in postmenopausal women—a clinical research center study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81:2250–2256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter RC 1988 Characterization of the acid-labile subunit of the growth hormone-dependent insulin-like growth factor binding protein complex. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 67:265–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamson G, Giudice LC, Rosenfeld RG 1991 Insulin-like growth factor binding proteins: structural and molecular relationships. Growth Factors 5:19–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Roith D, Bondy C, Yakar S, Liu JL, Butler A 2001 The somatomedin hypothesis: 2001. Endocr Rev 22:53–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelen CA, Koppeschaar HP, de Vries WR, Snel YE, Doerga ME, Zelissen PM, Thijssen JH, Blankenstein MA 1997 Visceral adipose tissue is associated with circulating high affinity growth hormone-binding protein. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82:760–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buijs MM, Burggraaf J, Wijbrandts C, de Kam ML, Frolich M, Cohen AF, Romijn JA, Sauerwein HP, Meinders AE, Pijl H 2003 Blunted lipolytic response to fasting in abdominally obese women: evidence for involvement of hyposomatotropism. Am J Clin Nutr 77:544–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijl H, Langendonk JG, Burggraaf J, Frolich M, Cohen AF, Veldhuis JD, Meinders AE 2001 Altered neuroregulation of GH secretion in viscerally obese premenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:5509–5515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weltman A, Despres JP, Clasey JL, Weltman JY, Wideman L, Kanaley J, Patrie J, Bergeron J, Thorner MO, Bouchard C, Hartman ML 2003 Impact of abdominal visceral fat, growth hormone, fitness, and insulin on lipids and lipoproteins in older adults. Metabolism 52:73–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KK, Biller BM, Lipman JG, Bradwin G, Rifai N, Klibanski A 2005 Truncal adiposity, relative growth hormone deficiency, and cardiovascular risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:768–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]