Abstract

Background and purpose:

Amiodarone (2-n-butyl-3-[3,5 diiodo-4-diethylaminoethoxybenzoyl]-benzofuran, B2-O-CH2CH2-N-diethyl) is an effective class III antiarrhythmic drug demonstrating potentially life-threatening organ toxicity. The principal aim of the study was to find amiodarone analogues that retained human ether-a-go-go-related protein (hERG) channel inhibition but with reduced cytotoxicity.

Experimental approach:

We synthesized amiodarone analogues with or without a positively ionizable nitrogen in the phenolic side chain. The cytotoxic properties of the compounds were evaluated using HepG2 (a hepatocyte cell line) and A549 cells (a pneumocyte line). Interactions of all compounds with the hERG channel were measured using pharmacological and in silico methods.

Key results:

Compared with amiodarone, which displayed only a weak cytotoxicity, the mono- and bis-desethylated metabolites, the further degraded alcohol (B2-O-CH2-CH2-OH), the corresponding acid (B2-O-CH2-COOH) and, finally, the newly synthesized B2-O-CH2-CH2-N-pyrrolidine were equally or more toxic. Conversely, structural analogues such as the B2-O-CH2-CH2-N-diisopropyl and the B2-O-CH2-CH2-N-piperidine were significantly less toxic than amiodarone. Cytotoxicity was associated with a drop in the mitochondrial membrane potential, suggesting mitochondrial involvement. Pharmacological and in silico investigations concerning the interactions of these compounds with the hERG channel revealed that compounds carrying a basic nitrogen in the side chain display a much higher affinity than those lacking such a group. Specifically, B2-O-CH2-CH2-N-piperidine and B2-O-CH2-CH2-N-pyrrolidine revealed a higher affinity towards hERG channels than amiodarone.

Conclusions and implications:

Amiodarone analogues with better hERG channel inhibition and cytotoxicity profiles than the parent compound have been identified, demonstrating that cytotoxicity and hERG channel interaction are mechanistically distinct and separable properties of the compounds.

Keywords: amiodarone, hepatic toxicity, pulmonary toxicity, hERG channel, class III antiarrhythmics

Introduction

Pharmacological treatment of cardiac arrhythmias is a difficult therapeutic challenge. One of the most effective antiarrhythmic drugs currently in use is amiodarone (2-n-butyl-3-[3,5 diiodo-4-diethylaminoethoxybenzoyl]-benzofuran, B2-O-CH2CH2-N-diethyl (1 in Table 1)), a class III antiarrhythmic agent with additional class I and II properties. This compound blocks human ether-a-go-go-related protein (hERG) channels, leading to the prolongation of the refractoriness and resulting in QT prolongation (Singh, 1996). In addition, amiodarone inhibits the rapid sodium current into human cardiomyocytes (Lalevee et al., 2003) and the slow inward calcium currents mediated through L-type calcium channels (Ding et al., 2001), and has been shown to be a non-competitive antagonist of cardiac β-adrenoreceptors (Chatelain et al., 1995). Amiodarone (see Table 1 for chemical structures and International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) names) is metabolized through mono- (Flanagan et al., 1982) and bis-desalkylation (Ha et al., 2005) to the corresponding secondary (B2-O-CH2CH2-NH-ethyl (2)) and primary amine (B2-O-CH2CH2-NH2 (3)), respectively. The primary amine 3 can subsequently be transaminated and oxidized to the corresponding acid (B2-O-CH2-COOH (5)) or primary alcohol (B2-O-CH2CH2-OH (6)) (Ha et al., 2005).

Table 1.

Chemical structures and lipophilicity of amiodarone, amiodarone metabolites and amiodarone analogues

Amiodarone's therapeutic use is limited because of its numerous side effects that include thyroidal (Harjai and Licata, 1997), pulmonary (Jessurun et al., 1998), ocular (Pollak, 1999) and/or liver toxicity (Morse et al., 1988; Lewis et al., 1989). The mechanisms leading to the toxicity of amiodarone are not completely understood, but are assumed to involve accumulation of the parent compound as well as metabolites, resulting in cellular toxicity, possibly by impairing mitochondrial function. Amiodarone is known to uncouple oxidative phosphorylation and to inhibit the electron transport chain and β-oxidation of fatty acids in mitochondria (Fromenty et al., 1990a, 1990b; Spaniol et al., 2001; Kaufmann et al., 2005; Waldhauser et al., 2006).

The most serious non-cardiac side effect of amiodarone is pulmonary toxicity. Clinically, pulmonary toxicity of amiodarone is characterized by progressive dyspnoea and impaired alveolar diffusion at first, of oxygen and then, finally, of carbon dioxide. Amiodarone-induced lung damage, as measured radiologically, is caused by interstitial fibrosis (Mason, 1987; Martin and Rosenow, 1988a, 1988b; Pitcher, 1992). It is possible that alveolar macrophages may play a role in the pulmonary fibrosis associated with amiodarone (Jessurun et al., 1998). Interestingly, Bigler et al. (2007) were recently able to show that some modifications of the diethyl-amino-ethoxy group of amiodarone reduced its toxicity towards alveolar macrophages.

In earlier studies, we demonstrated that the substituents attached to the benzofuran ring (aliphatic side chain in position 2 and iodinated 4-diethyl-amino-ethoxy-benzoyl chain in position 3) are responsible for mitochondrial toxicity caused by amiodarone (Spaniol et al., 2001; Kaufmann et al., 2005). More recent studies focusing on the hepatotoxic profile and the antiarrhythmic effect of amiodarone and amiodarone analogues again revealed the importance of the topology of the side chain attached to the bicyclic aromatic template (B2, see Table 1) of amiodarone for both interaction with the hERG channel and hepatocellular toxicity (Waldhauser et al., 2006).

Despite these studies, questions regarding the interaction with the hERG channels and cytotoxicity of amiodarone and amiodarone analogues with different compositions of the aliphatic side chain attached to B2 remained unanswered. The current study was designed to address following issues: first, are amiodarone and related derivatives also toxic to cultured pneumocytes and is this toxicity similar to that seen in cultured hepatocytes? Second, is there a correlation between the physico-chemical properties of these compounds with hERG inhibition and/or cellular toxicity?

We therefore synthesized and investigated the ethyl ester B2-O-CH2-COO-CH2CH3 (11) of the acid B2-O-CH2-COOH (5), as well as two derivatives with either a terminal pyrrolidine (B2-O-CH2CH2-N-pyrrolidine (8)) or piperidine (B2-O-CH2CH2-N-piperidine (9)) group, respectively. In addition, we investigated the two amines 2 and 3 (two amiodarone metabolites), as well as the bis-isopropyl amine B2-O-CH2CH2-N-diisopropyl (4), three compounds we had investigated already in a previous study (Waldhauser et al., 2006). The data generated in the current investigation could then be compared with those of our previous study (Waldhauser et al., 2006).

Materials and methods

Amiodarone and amiodarone derivatives

Amiodarone hydrochloride was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Buchs, Switzerland). All amiodarone analogues were synthesized starting from B2 (Ha et al., 2000) as shown in Table 1 and as described earlier for B2-O-CH2CH2-NH-ethyl (2), B2-O-CH2CH2-NH2 (3), B2-O-CH2CH2-N-diisopropyl (4), B2-O-CH2-COOH (5), B2-O-CH2CH2-OH (6), B2-O-CH2CH2-NH-CO-CH2CH3 (7) and B2-O-CH2CH3 (10) (Waldhauser et al., 2006) and for B2-O-CH2-COO-CH2CH3 (11) (Ha et al., 2005). The remaining two amiodarone derivatives were synthesized as follows:

B2-O-CH2CH2-N-piperidine [(2-butyl-benzofuran-3-yl)-[3,5-diiodo-4-(2-piperidine-1-yl-ethoxy)phenyl]-methanone hydrochloride] (9)

To a mixture of B2 (2 g, 3.66 mmol; for chemical structure see Table 1) and K2CO3 (3.45 g, 25 mmol) in toluene/water (2:1 v/v, total volume: 75 mL) heated to 55–60 °C, small portions of about 0.2 g 1-(2-chlorethyl) piperidine monohydrochloride (3.41 g, 18.5 mmol) were added. After the addition, the temperature was raised to reach reflux over 30 min. The yellow colour of B2 disappeared. After having refluxed the reaction mixture for one additional hour, the phases were quickly separated using a separation funnel at 60 °C. The toluene phase was washed three times with 25 mL water at this temperature, and the organic phase was evaporated to dryness later. The residue was suspended in 10 mL 5% NH3, and B2-O-Et-NH-ethyl was extracted three times with 15 mL toluene. The organic phase was separated by means of centrifugation and evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure. Then, 2 mL 10 N HCl and 15 mL toluene were added to the residue, and the liquids were removed under reduced pressure at 80 °C. A white solid residue was obtained after three additional treatments with 10 mL toluene. The residue was then crystallized from toluene and yielded 1.62 g (64%) of the target product. Analytically pure 9 was obtained by silica gel low-pressure chromatography ((30 cm × 5 cm i.d.) and mobile phase: methanol: 25% NH3 (99:1 v/v)). Melting point, electrospray ionization-MS and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy data of B2-O-Et-N-piperidine (9) have been reported already in our previous communication (Bigler et al., 2007).

B2-O-CH2CH2-N-pyrrolidine [(2-butyl-benzofuran-3-yl)-[3,5-diiodo-4-(2-pyrrolidine-1-yl-ethoxy)-phenyl]-methanone hydrochloride] (8)

B2-O-CH2CH2-N-pyrrolidine (8) (yield 70%) was prepared in the same manner as described for 9. The electrospray ionization-MS and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy data supporting its chemical structure were published previously (Bigler et al., 2007).

Octanol/water partition coefficient of amiodarone and derivatives

The octanol/water partition of the compounds synthesized was determined using reversed phase HPLC as described by Braumann (1986b). HPLC of the substances was performed at 37 °C using different 5 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4)/methanol mixtures as an eluent. Log D, the ratio of the equilibrium concentrations of all species (un-ionized and ionized) of a molecule in octanol to the same species in the water phase, was calculated from the determined octanol/water partition (Braumann, 1986b).

Other chemicals

All chemicals used were from Sigma-Aldrich except for 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide (JC-1), which was from Alexis Biochemicals (Lausen, Switzerland). All cell culture media were obtained from Gibco (Paisley, UK). The 96-well plates were from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Cell lines and cell culture

The hepatoma cell line HepG2 was provided by Professor Dietrich von Schweinitz (University Hospital Basel, Switzerland) and HepT1 cells from Professor Torsten Pietsch (University of Bonn, Germany). A549 cells were a generous gift from Dr Juillerat (University Institute of Pathology, University Hospital Lausanne, Switzerland). HepG2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (with 2 mM GlutaMAX, 1.0 g L−1 glucose and sodium bicarbonate) supplemented with 10% (v/v) inactivated foetal calf serum, 10 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.2, 100 U mL−1 penicillin–streptomycin and non-essential amino acids. HepT1 cells were grown in RPMI supplemented with 10% (v/v) inactivated foetal calf serum, 10 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.2, 2 mM GlutaMAX (Invitrogen, Basel, Switzerland) and 100 U mL−1 penicillin–streptomycin. The A549 cell line was cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (with 4 mM GlutaMAX, 4.5 g L−1 glucose and sodium bicarbonate) supplemented with 10% (v/v) inactivated foetal calf serum, 10 mM HEPES buffer pH 7.2, non-essential amino acids and 100 U mL−1 penicillin–streptomycin. The culture conditions were 5% CO2 and 95% air atmosphere at 37 °C. Cells were seeded at a density of 70 000 cells per well on a 96-multiwell plate and allowed to settle overnight before experimentation.

Adenylate kinase release

The loss of cell membrane integrity results in the release of adenylate kinase (AK), which can be quantified using the firefly luciferase system (ToxiLight BioAssay Kit; Cambrex Bio Science, Rockland, ME, USA). After an incubation of 4 or 24 h, 100 μL assay buffer was added to 20 μL supernatant from cells treated with amiodarone or amiodarone derivates (concentrations indicated in the tables and figures) and the luminescence was measured after 5 min of incubation.

Reductive capacity of the cells

The fluorescent dye Alamar Blue (AbD Serotec, Oxford, UK) was used for this purpose. Proliferating cells cause the change of the oxidized form of blue and non-fluorescent Alamar Blue (resazurin) to a pink, highly fluorescent and reduced form (resorufin) that can be detected using the fluorescence mode (excitation 560 nm; emission 590 nm) (O'Brien et al., 2000). The dye was added to the cells together with the test substances at a final concentration of 10% and the fluorescence was measured after 4 and 24 h.

Mitochondrial membrane potential

The mitochondrial membrane potential was measured with the dye JC-1 according to current protocols of flow cytometry with minor modifications and quantified as described previously (Kaufmann et al., 2006). HepG2 and A549 cells were harvested by trypsinization and adjusted to 105 cells per 0.5 mL with pre-warmed Dulbecco's medium without phenol red containing 1% FCS. The compounds to be tested were then added to the cells and incubated for 24 h. After the incubation period, JC-1 stock solution (0.25 μg 100 μL−1 for 100 000 cells) was added to the incubations and cells were incubated at 37 °C in the dark for 10 min. The cell suspension was then washed once by adding 1.5 mL PBS and the cells were sedimented by centrifugation at 500 g for 4 min at room temperature. Cells were resuspended in 0.3 mL PBS and analysed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) using the following settings: acquisition=max 300 events s−1; FSC/SSC: E-01 –5.08 (A549: 6.23)/479–1.00; FL1: 400; FL2: 324; compensation: FL2−54.4% FL1.

HEK Tet cells expressing hERG channels

The interaction of the test substances with the hERG channel (nomenclature of ion channels according to Alexander et al., 2008) was examined using HEK Tet cells stably expressing this potassium channel. Briefly, a human cardiac plasmid cDNA library was prepared from freshly isolated tissue. The hERG α-subunit PCR product was released from the pCR2.1-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) for ligation into a modified pcDNA5/FRT/TO vector (Invitrogen) with excluded BGH site. Restriction analysis and complete sequencing confirmed the correct composition and expression of the hERG α-subunit in the plasmid. HEK Tet cells were transfected with the calcium phosphate precipitation method (Invitrogen). Clones were selected with 200 μg mL−1 hygromycin B and 30 μg mL−1 blasticidin (Invitrogen) and checked back electrophysiologically. Using limited dilution, clone HEK Tet hERG S12, which displayed an average tail current amplitude of approximately 700–1500 pA, was isolated. This clone was successfully cultured over 100 passages without detectable loss of current density and was used in the current studies. The cells were generally maintained in HAM/F12 with GlutaMax I (Gibco) supplemented with 9% foetal bovine serum (Gibco), 0.9% penicillin–streptomycin solution (Gibco) and 100 μg mL−1 hygromycin B and 15 μg mL−1 blasticidin (Invitrogen). For electrophysiological measurements, the cells were seeded onto 35 mm sterile culture dishes containing 2 mL culture medium and 1 μg mL−1 tetracycline for induction of channel expression (overnight). Confluent clusters of HEK cells are electrically coupled. Because responses in distant cells are not adequately voltage clamped and because of uncertainties about the extent of coupling, cells were cultured at a density enabling single cells to be used for the experiments.

Electrophysiology

hERG currents were measured by means of the patch-clamp technique in the whole-cell configuration as described previously (Waldhauser et al., 2006).

Molecular modelling

Model building of hERG was performed on the structure of the prototypical potassium channel KcsA, for which the X-ray crystal structure has been resolved (Doyle et al., 1998; Zhou et al., 2001). Modelling calculations were done on a Dell 670 workstation using the program Moloc (Gerber, 1998). An initial C-α model of hERG was built by fitting its aligned sequence on the potassium channel template C-α structure followed by optimization of newly introduced loops. Subsequently, a full atom model was generated and newly inserted loops were optimized with the rest of the protein kept stationary. Refinement of the full model with manual removal of repulsive interactions followed and was divided into three subsequent steps. First, only amino-acid side chains were allowed to move. In the second step, all atoms except α-carbons were optimized and, finally, all atoms were allowed to move, however, with positional constraints for α-carbons. Quality checks were made with Moloc internal programs.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean±s.e.mean of at least three individual experiments. Differences between groups (control and test compound incubations) were analysed by ANOVA and Dunnett's post hoc test was performed if ANOVA showed significant differences. A P-value ⩽0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

The principal aim of the study was to determine whether the interaction with the hERG channel (which is considered to represent a pharmacological action of amiodarone; Singh, 1996) can be differentiated from the cytotoxicity of amiodarone analogues carrying different side chains. Hence, amiodarone analogues with different side chains (containing no nitrogen, a nitrogen with one or two aliphatic side chain or a nitrogen built into a cyclic structure to prevent N-desalkylation in vivo) were synthesized and tested for their cytotoxicity profile and hERG channel interaction properties.

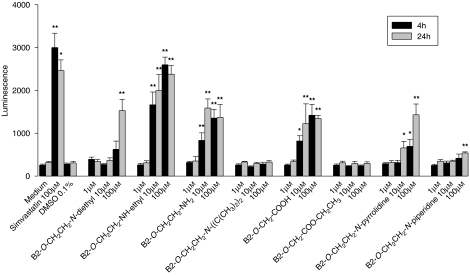

Toxicity on HepG2 cells

As shown in Figures 1 and 2, the results obtained by the two assays used (ToxiLight and Alamar Blue assays) are qualitatively comparable. In the ToxiLight assay, the most toxic compounds tested were the desethylated amiodarone metabolites 2 and 3 (see Table 1 for structures), as well as the B2-O-CH2-COOH (5), which were toxic in the range of 1–10 μM. Amiodarone, as well as the piperidine 9 and the pyrrolidine 8 were less toxic, with cytotoxicity starting only at 100 μM. The diisopropyl molecule 4 and the ethyl ester of 5 B2-O-CH2-COO-CH2CH3 (11) were not cytotoxic at concentrations below 100 μM. However, the time of exposure also had a critical influence on the toxicity of the individual compounds. For amiodarone (1) and the pyrrolidine analogue 8, an incubation period of 12 h produced more toxic effects compared with incubations of 4 h.

Figure 1.

Adenylate kinase release from HepG2 cells treated with amiodarone or amiodarone analogues. B2-O-CH2CH2-NH-ethyl, B2-O-CH2CH2-NH2, B2-O-CH2-COOH and B2-O-CH2CH2-N-pyrrolidine showed cytotoxicity starting at 10 μM, amiodarone and B2-O-CH2CH2-N-piperidine starting at 100 μM, and B2-O-CH2CH2-N-diisopropyl and B2-O-CH2-COO-CH2CH3 no cytotoxicity up to 100 μM. Simvastatin was used as a positive control. All samples contained 0.1% dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) (except medium only). Data are presented as means±s.e.mean of at least four incubations in triplicate. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 versus control incubations containing 0.1% DMSO.

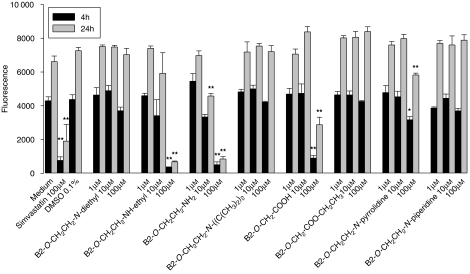

Figure 2.

Inhibition of reductive capacity of HepG2 cells (resazurin reduction test) by amiodarone or amiodarone derivatives. B2-O-CH2CH2-NH2 inhibited reductive capacity starting at 10 μM, B2-O-CH2CH2-NH-ethyl, B2-O-CH2-COOH and B2-O-CH2CH2-N-pyrrolidine at 100 μM, and amiodarone, B2-O-CH2CH2-N-diisopropyl, B2-O-CH2-COO-CH2CH3 and B2-O-CH2CH2-N-piperidine revealed no inhibition up to 100 μM. Simvastatin was used as a positive control. All samples contained 0.1% dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) (except medium only). Data are presented as means±s.e.mean of at least four incubations in triplicate. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 versus control incubations containing 0.1% DMSO.

Interestingly, reductive capacity assessed using the Alamar Blue assay increased consistently with the duration of the incubation, irrespective of the presence or absence of our compounds (Figure 2). With this assay, toxic effects could be observed for the desethylated amiodarone metabolites 2 and 3, B2-O-CH2-COOH (5) and B2-O-CH2CH2-N-pyrrolidine (8), but only at concentrations of 100 μM. For amiodarone (1), the diisopropyl analogue 4, the ethylated acid 11 and the piperidine analogue 9, no toxicity could be demonstrated up to 100 μM.

The effect of amiodarone and amiodarone analogues on the mitochondrial membrane potential was comparable with the results obtained by the Alamar Blue Assay (Table 2). At concentrations of 10 μM, the mitochondrial membrane potential was significantly decreased only for the desethylated amiodarone metabolites 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 2.

Effects of amiodarone and analogues on mitochondrial membrane potential in HepG2 and A549 cells

| HepG2 | A549 | |

|---|---|---|

| Cell culture medium | 67±3.3 | 87±2.9 |

| Cell culture medium containing 0.1% DMSO | 67±3.5 | 87±2.9 |

| B2-O-CH2CH2-N-diethyl (amiodarone) (1) | 71±4.1 | 86±3.2 |

| B2-O-CH2CH2-NH-ethyl (2) | 19±4.9** | 9±3.9** |

| B2-O-CH2CH2-NH2 (3) | 10±1.8** | 8±1.3** |

| B2-O-CH2CH2-N-diisopropyl (4) | 61±2.1 | 89±2.1 |

| B2-O-CH2-COOH (5) | 58±5.0 | 74±5.5 |

| B2-O-CH2CH2-N-pyrrolidine (8) | 69±3.9 | 83±3.2 |

| B2-O-CH2CH2-N-piperidine (9) | 60±3.3 | 91±1.9 |

| B2-O-CH2-COO-CH2CH3 (11) | 59±4.1 | 76±7.4 |

**P<0.01 versus control incubations containing 0.1% DMSO.

The mitochondrial membrane potential was determined using the dye JC-1 as described in the Materials and methods. The concentration of amiodarone and analogues was 10 μM. The cells were incubated for 24 h with the indicated compounds. With the exception of control incubations (with culture medium only), all samples contained 0.1% DMSO. Data are presented as a percentage of cells containing mitochondria with a normal mitochondrial membrane potential (Kaufmann et al., 2006). The values represent means±s.e.mean of at least five experiments.

Toxicity on A549 cells

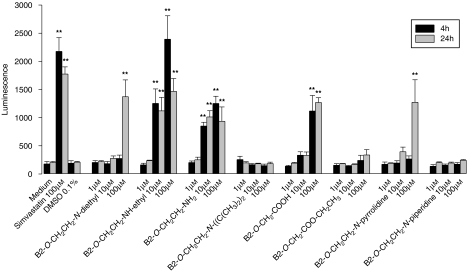

Similar to HepG2 cells, the most toxic compounds tested on A549 cells were the two amines 2 and 3, respectively, with cytotoxicity starting at 10 μM (Figure 3). For amiodarone (1), B2-O-CH2-COOH (5) and the pyrrolidine derivative 8, cytotoxicity was detected only at 100 μM, whereas the tertiary amine 4, the esterified acid 11 and the piperidine derivative 9 were not toxic up to 100 μM. As with HepG2 cells, a time-dependent toxicity of amiodarone (1) and the cyclic pyrrolidine analogue 8 was demonstrated.

Figure 3.

Adenylate kinase release from A549 cells treated with amiodarone or amiodarone derivatives. B2-O-CH2CH2-NH-ethyl and B2-O-CH2CH2-NH2 showed cytotoxicity starting at 10 μM, amiodarone, B2-O-CH2-COOH and B2-O-CH2CH2-N-pyrrolidine at 100 μM, and B2-O-CH2CH2-N-diisopropyl, B2-O-CH2-COO-CH2CH3 and B2-O-CH2CH2-N-piperidine no cytotoxicity up to 100 μM. Simvastatin was used as a positive control. All samples contained 0.1% dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) (except medium only). Data are presented as means±s.e.mean of at least four incubations in triplicate. **P<0.01 versus control incubations containing 0.1% DMSO.

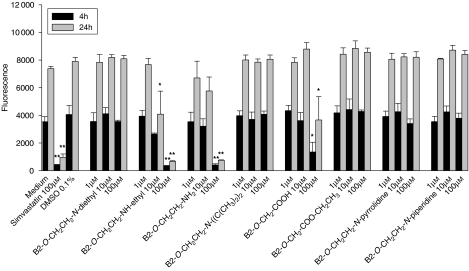

Concerning reductive capacity (Alamar Blue), the desethylamine metabolite 2 was toxic at 10 μM for 12 h, whereas the primary amine 3 and B2-O-CH2-COOH (5) impaired reductive capacity only at 100 μM (Figure 4). For amiodarone (1), the diisopropyl analogue 4, the ethylated acid 11 and the pyrrolidine 8 and the piperidine derivative 9, no toxicity could be demonstrated up to 100 μM.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of reductive capacity of A549 cells (resazurin reduction test) by amiodarone or amiodarone derivatives. B2-O-CH2CH2-NH-ethyl inhibited reductive capacity starting at 10 μM, B2-O-CH2CH2-NH2 and B2-O-CH2-COOH at 100 μM, and amiodarone, B2-O-CH2CH2-N-diisopropyl, B2-O-CH2-COO-CH2CH3, B2-O-CH2CH2-N-pyrrolidine and B2-O-CH2CH2-N-piperidine revealed no inhibition up to 100 μM. Simvastatin was used as a positive control. All samples contained 0.1% dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) (except medium only). Data are presented as means±s.e.mean of at least four incubations in triplicate. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 versus control incubations containing 0.1% DMSO.

The results obtained for the mitochondrial membrane potential using the dye JC-1 were very similar to those determined in HepG2 cells (Table 2). At concentrations of 10 μM, the mitochondrial membrane potential was significantly decreased only by the two desethylated amiodarone metabolites 2 and 3.

Effects on hERG channels

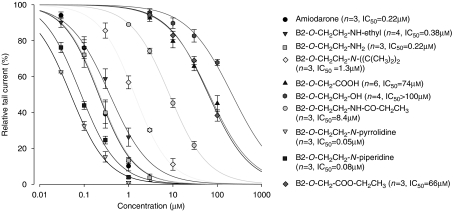

Amiodarone and its analogues were investigated for their inhibitory effects on hERG potassium channels stably expressed in HEK Tet cells. With the exception of B2-O-CH2CH3 (10), all measured compounds interfered with potassium transport by the hERG channels (Figure 5), with IC50 values ranging from 0.05 μM to >100 μM. The IC50 values for amiodarone (1), for the two desethylated metabolites 2 and 3, and for the cyclic analogues 8 and 9 were all lower than 1 μM, whereas those for B2-O-CH2CH2-N-diisopropyl (4) and B2-O-CH2CH2-NH-CO-CH2CH3 (7) ranged between 1 and 10 μM and the values for B2-O-CH2-COOH (5), B2-O-CH2CH2-OH (6), B2-O-CH2-COO-CH2CH3 (11) and B2-O-CH2CH3 (10) exceeded 10 μM or were not assessable. Individual traces describing the interactions with hERG channels are provided in Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Dose–response curves of amiodarone and amiodarone derivatives. Amiodarone, the amiodarone metabolites B2-O-CH2CH2-NH-ethyl and B2-O-CH2CH2-NH2, and the analogues B2-O-CH2CH2-N-pyrrolidine and B2-O-CH2CH2-N-piperidine revealed strong hERG inhibition with IC50<1 μM. B2-O-CH2CH2-N-diisopropyl and B2-O-CH2CH2-NH-CO-CH2CH3 were medium strong inhibitors (IC50>1 and <10 μM), whereas B2-O-CH2-COOH, B2-O-CH2CH2-OH and B2-O-CH2-COO-CH2CH3 showed only a weak inhibition. For B2-O-CH2CH2-OH, the IC50 was not calculated as the inhibition of the hERG channel was <50% at 100 μM. For B2-O-CH2CH3 (not shown in the figure), no inhibition of the hERG channel was detectable up to 10 μM and higher concentrations could not be tested due to solubility problems. Measurements were accomplished in the whole-cell patch-clamp configuration at room temperature. Outward currents were activated upon depolarization of the cell membrane from −80 to +20 mV for 3 s, whereas partial repolarization to −40 mV for 4 s evoked large tail currents. At least three cells were recorded per test compound.

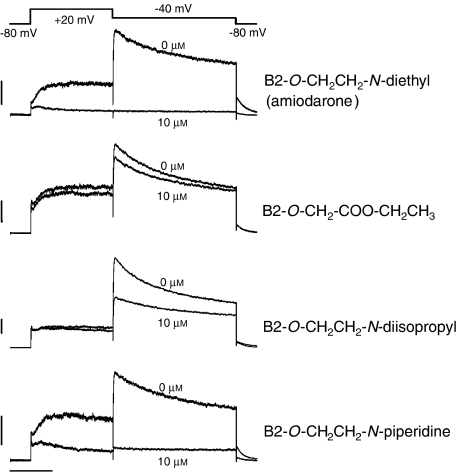

Figure 6.

Inhibition of the potassium current by B2-O-CH2CH2-N-diethyl (amiodarone (1)), B2-O-CH2-COO-CH2CH3 (11), B2-O-CH2CH2-N-diisopropyl (4) and B2-O-CH2CH2-N-piperidine (9). Representative traces of potassium currents across hERG channels stably expressed in HEK Tet cells are shown. Measurements were accomplished in the whole-cell patch-clamp configuration at room temperature. Outward currents were activated upon depolarization of the cell membrane from −80 to +20 mV for 3 s, whereas partial repolarization to −40 mV for 4 s evoked large tail currents. At least three cells were recorded per test compound. The vehicle (0.1% dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO)) had no significant effect on hERG channel activity. In contrast, 10 μM B2-O-Et-N-diethyl (amiodarone (1)) as well as 10 μM B2-O-CH2CH2-N-piperidine (9) blocked the hERG channel completely. In comparison, the interaction of 10 μM B2-O-CH2-COO-CH2CH3 (11) as well as 10 μM B2-O-CH2CH2-N-diisopropyl (4) with the hERG channel was less intense. The upper trace in the individual figures depicts the control incubations (0.1% DMSO) and the lower trace the incubations containing the test compounds in 0.1% DMSO.

Molecular modelling of hERG inhibitor interactions

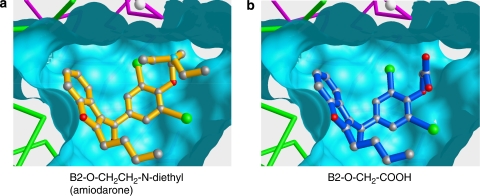

The structure of a tetraethyl ammonium-inhibited fragment of the KcsA potassium channel roughly resembles an amphora (Morais-Cabral et al., 2001). The sequence alignment of the hERG protein with the KcsA channel suggests that the relevant part of the hERG structure (vestibule and neck of the amphora) is likely to be conserved in both proteins. A model of vestibule and selectivity filter of the hERG channel (neck of the amphora) was therefore produced using the KcsA structure as a structural template (Figure 7). Amiodarone (1) and some of its metabolites and/or analogues were docked manually into the hERG model such that the charged basic nitrogen of 1 could mimic position and function of the ammonium nitrogen of tetraethyl ammonium in the KcsA structure (Figure 7a, left panel). Access for solvated potassium ions to the narrow selectivity filter would be blocked by 1 in the energetically most favoured inhibitor position. Metabolite B2-O-CH2-COOH (5, Figure 7b), which is lacking a positively ionizable nitrogen, but carries a negatively ionizable terminal carboxylate instead, could theoretically assume a similar position inside the rather hydrophobic vestibule. However, the positively charged diethyl amino group of 1 is replaced by a shorter side chain in 5 that is bearing a terminal negatively ionizable carboxylate. The inversion of charge in the side chain of 5 leads to dramatically lowered attractive interactions with the channel, most likely due to unfavourable electrostatic interferences. The strong affinity of amiodarone (1), amiodarone metabolites 2, 3 and some analogues 8, 9 is clearly dependent on a positively ionizable group in the side chain (Table 1), whereas molecules with a neutral or even negatively charged side chain display significantly lowered affinities for the hERG channel.

Figure 7.

(a) Amiodarone (yellow) is docked into the vestibule of a hERG model. Two of the four chains of the hERG homo-tetramer are shown in C-α representation (green, magenta). The Connolly surface was produced with a probe radius of 1.4 Å. The selectivity filter cannot be displayed in this representation due to its very narrow diameter. A white ball represents a potassium ion in the filter region as found in the KscA structure template (Morais-Cabral et al., 2001). (b) Amiodarone derivative 5 (blue) is docked in a hypothetical position similar to the one assumed by 1. From the apparent positional similarity of 1 and 5, it can be deduced that the positively charged nitrogen (seen in 1 as the blue ball) has an attractive effect. The negatively charged carboxylate of 5, being in a position similar to that of the positively charged nitrogen in 1, induces strong repulsive effects.

Discussion and conclusions

Our results demonstrate that the cytotoxicity found for amiodarone and some of its analogues does not necessarily parallel their interaction with the hERG channel (see Table 3 for on overview of the results).

Table 3.

Overview of the toxicological and pharmacological effects of amiodarone and the amiodarone analogues investigated

| Compounds | LDH release (HepG2 cells)a | AK release (HepG2 cells) | Resazurin reduction (HepG2 cells) | AK release (A549 cells) | Resazurin reduction (A549 cells) | MMP depolarization | IC50 hERG channels (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B2-O-CH2CH2-N-diethyl (amiodarone) (1) | ++ | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0.22 |

| B2-O-CH2CH2-NH-ethyl (2) | +++ | +++ | + | +++ | ++ | + | 0.38 |

| B2-O-CH2CH2-NH2 (3) | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | + | + | 0.22 |

| B2-O-CH2CH2-N-diisopropyl (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.3 |

| B2-O-CH2-COOH (5) | + | +++ | + | ++ | + | 0 | 74 |

| B2-O-CH2CH2-OH (6) | ++ | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | >100 |

| B2-O-CH2CH2-NH-CO-CH2CH3 (7) | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 8.4 |

| B2-O-CH2CH2-N-pyrrolidine (8) | ND | ++ | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0.05 |

| B2-O-CH2CH2-N-piperidine (9) | ND | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.08 |

| B2-O-CH2CH3 (10) | 0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | NAb |

| B2-O-CH2-COO-CH2CH3 (11) | ND | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 66 |

Abbreviations: AK, adenylate kinase; hERG, human ether-a-go-go-related protein; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MMP, mitochondrial membrane potential; ND, not determined.

Obtained from Waldhauser et al. (2006).

NA: not accessible (no inhibition of hERG channels up to 100 μM, higher concentrations were not soluble).

The grading of the effects was as follows. For lactate dehydrogenase leakage: +P<0.05 at 100 μM, ++P<0.01 at 100 μM and +++P<0.05 at 10 μM. For adenylate kinase release: +P<0.05 at 100 μM, ++P<0.01 at 100 μM and +++P<0.05 at 10 μM. For reductive capacity: +P<0.05 at 100 μM, ++P<0.05 at 100 μM and +++P<0.01 at 100 μM. For mitochondrial membrane potential depolarization: +P<0.05 and ++P<0.01 at 10 μM in HepG2 and A549 cell lines.

In both cell lines investigated, the desethylated amiodarone metabolites 2 and 3 were more toxic than amiodarone itself, a finding of potential clinical importance. Similar observations have been reported in previous studies for HepG2 cells (Waldhauser et al., 2006) and also for alveolar and bronchiolar epithelial cells (Bolt et al., 2001a). As mono- and bis-desethylation of amiodarone are primarily performed by CYP3A4 (Fabre et al., 1993; Ha et al., 1996), co-administration of CYP3A4 inducers to patients treated with amiodarone may enhance its toxicity. However, clinical evidence for this assumption is so far lacking.

Our findings on mitochondrial toxicity of amiodarone and some of its metabolites or analogues are in accord with data from previous studies. Several studies have already described hepatic mitochondrial toxicity of amiodarone and amiodarone metabolites or analogues in vivo (Fromenty et al., 1990b) and in vitro (Fromenty et al., 1990a, 1990b; Spaniol et al., 2001; Kaufmann et al., 2005; Waldhauser et al., 2006). Amiodarone and metabolites appear to target mitochondria in organs and cells other than liver or hepatocytes, such as the lung (Card et al., 1998, 2003; Bolt et al., 2001a) and in lymphocytes (Yasuda et al., 1996). It is therefore not surprising that the toxic effects observed in our investigations were almost identical in HepG2 and A549 cells.

Pulmonary toxicity exerted by amiodarone is dose dependent and may affect up to 5% of patients treated with this agent (Jessurun et al., 1998). The clinical significance of this adverse drug reaction is such that morbidity is considerable (patients usually present with coughing and progressive dyspnoea) and that patients may die, if treatment is not stopped early enough. In comparison, symptomatic liver injury appears to be less frequent than pulmonary toxicity, with 1–3% of patients being affected (Lewis et al., 1989).

The underlying mechanisms leading to organ damage in patients treated with amiodarone are not fully elucidated. Accumulation of phospholipids (phospholipidosis) occurs in most organs of patients or animals treated with this drug (Lullmann et al., 1975) and is considered to reflect impairment of phospholipid breakdown due to inhibition of lysosomal phospholipidases by amiodarone and/or its metabolites (Hostetler et al., 1986, 1988). Lipophilic, weak bases such as amiodarone and some of its basic metabolites or analogues may be accumulated in lysosomes (Kaufmann and Krise, 2007) thereby leading to phospholipidosis. However, the long-term implications of phospholipidosis in liver and/or lung damage remains unclear (Kaufmann and Krise, 2007). Although phospholipidosis is a dose-dependent, general phenomenon, lung and liver damage only occur in a small fraction of patients treated with amiodarone, suggesting that individual risk factors may be involved in the manifestation of these adverse reactions.

Mitochondrial toxicity could well explain steatohepatitis observed in patients treated with amiodarone (Lewis et al., 1989, 1990). However, this mechanism may not explain the development of pulmonary fibrosis. In hamsters treated intratracheally with amiodarone, pulmonary fibrosis was present after 3 weeks of treatment and was preceded by mitochondrial damage (reduced activity of the respiratory chain) and increased expression of transforming growth factor-β1 (Bolt et al., 2001b; Card et al., 2003). Interestingly, vitamin E prophylaxis prevented overexpression of transforming growth factor-β1 and subsequent pulmonary fibrosis but not the mitochondrial damage. It is possible therefore that mitochondrial damage is one of the initial events, ultimately leading to a progression to pulmonary fibrosis. Pre-existing mitochondrial damage could therefore represent a risk factor for organ toxicity. As observed for other drugs causing mitochondrial toxicity (for example, valproic acid) (Krahenbuhl et al., 2000), the existence of such risk factors may explain why only a fraction of the patients treated with amiodarone develop symptomatic adverse drug reactions.

Our study demonstrates that the interaction of amiodarone with the hERG channel is strongly favoured by the presence of a basic nitrogen connected through a flexible linker to an aromatic moiety in the molecule. The basic nitrogen appears to be crucial for a tight interaction with the protein, as compounds lacking such a basic functionality such as B2-O-CH2-COOH (5), B2-O-CH2CH2-OH (6), B2-O-CH2CH3 (10) or B2-O-CH2-COO-CH2CH3 (11) displayed significantly higher IC50 values (range 66–216 μM) than compounds comprising a charged nitrogen (range 0.05–8.4 μM). Importantly, cellular toxicity of individual substances did not correlate with an affinity for hERG channel, as clearly shown for B2-O-CH2-COOH (5) that lacks a basic nitrogen but is highly cytotoxic. Furthermore, desalkylation of the basic nitrogen of amiodarone (1) is associated with increased cytotoxicity, but leaves the affinity of the metabolites for the hERG channel unchanged. Most interestingly, the basic piperidine derivative 9 revealed a low cytotoxicity but a very high affinity for the hERG channel (IC50 0.08 μM). Cyclization of the ethyl groups attached to the nitrogen in the side chain of amiodarone, as shown for the pyrrolidine derivative 8, may increase the affinity to the hERG channel, but may also decrease toxicity.

In conclusion, we have provided quantitative cytotoxicity data for amiodarone and some of its key metabolites in hepatic and pulmonary cell lines. Furthermore, the affinity of these compounds for the hERG channel is critically dependent on the presence of a positively ionizable nitrogen in the side chain. As there was no correlation between cytotoxicity and affinity for the hERG channel, our results suggest the possibility of developing amiodarone analogues with maintained or even increased affinity for hERG channels but with a decreased cytotoxicity.

Acknowledgments

This study has been supported by grant 310000-112483/1 from the Swiss National Science Foundation to SK.

Abbreviations

- hERG

human ether-a-go-go-related protein

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Alexander SP, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 3rd edition. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153 Suppl 2:S1–S209. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigler L, Spirli C, Fiorotto R, Pettenazzo A, Duner E, Baritussio A, et al. Synthesis and cytotoxicity properties of amiodarone analogues. Eur J Med Chem. 2007;42:861–867. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2006.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolt MW, Card JW, Racz WJ, Brien JF, Massey TE. Disruption of mitochondrial function and cellular ATP levels by amiodarone and N-desethylamiodarone in initiation of amiodarone-induced pulmonary cytotoxicity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001a;298:1280–1289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolt MW, Racz WJ, Brien JF, Massey TE. Effects of vitamin E on cytotoxicity of amiodarone and N-desethylamiodarone in isolated hamster lung cells. Toxicology. 2001b;166:109–118. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(01)00451-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braumann T. Determination of hydrophobic parameters by reversed-phase liquid chromatography: theory, experimental techniques, and application in studies on quantitative structure–activity relationships. J Chromatogr. 1986a;373:191–225. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)80213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braumann T. Determination of hydrophobic parameters by reversed-phase liquid chromatography: theory, experimental techniques, and application in studies on quantitative structure–activity relationships. J Chromatogr. 1986b;373:191–225. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)80213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Card JW, Lalonde BR, Rafeiro E, Tam AS, Racz WJ, Brien JF, et al. Amiodarone-induced disruption of hamster lung and liver mitochondrial function: lack of association with thiobarbituric acid-reactive substance production. Toxicol Lett. 1998;98:41–50. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(98)00097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Card JW, Racz WJ, Brien JF, Massey TE. Attenuation of amiodarone-induced pulmonary fibrosis by vitamin E is associated with suppression of transforming growth factor-beta1 gene expression but not prevention of mitochondrial dysfunction. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:277–283. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.043208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatelain P, Meysmans L, Matteazzi JR, Beaufort P, Clinet M. Interaction of the antiarrhythmic agents SR 33589 and amiodarone with the beta-adrenoceptor and adenylate cyclase in rat heart. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;116:1949–1956. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb16397.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding S, Chen F, Klitzner TS, Wetzel GT. Inhibition of L-type Ca2+ channel current in Xenopus oocytes by amiodarone. J Investig Med. 2001;49:346–352. doi: 10.2310/6650.2001.33900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle DA, Morais Cabral J, Pfuetzner RA, Kuo A, Gulbis JM, Cohen SL, et al. The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 1998;280:69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabre G, Julian B, Saint-Aubert B, Joyeux H, Berger Y. Evidence for CYP3A-mediated N-deethylation of amiodarone in human liver microsomal fractions. Drug Metab Dispos. 1993;21:978–985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan RJ, Storey GC, Holt DW, Farmer PB. Identification and measurement of desethylamiodarone in blood plasma specimens from amiodarone-treated patients. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1982;34:638–643. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1982.tb04692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromenty B, Fisch C, Berson A, Letteron P, Larrey D, Pessayre D. Dual effect of amiodarone on mitochondrial respiration. Initial protonophoric uncoupling effect followed by inhibition of the respiratory chain at the levels of complex I and complex II. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990a;255:1377–1384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromenty B, Fisch C, Labbe G, Degott C, Deschamps D, Berson A, et al. Amiodarone inhibits the mitochondrial beta-oxidation of fatty acids and produces microvesicular steatosis of the liver in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990b;255:1371–1376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber PR. Charge distribution from a simple molecular orbital type calculation and non-bonding interaction terms in the force field MAB. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 1998;12:37–51. doi: 10.1023/a:1007902804814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha HR, Bigler L, Wendt B, Maggiorini M, Follath F. Identification and quantitation of novel metabolites of amiodarone in plasma of treated patients. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2005;24:271–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha HR, Candinas R, Stieger B, Meyer UA, Follath F. Interaction between amiodarone and lidocaine. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1996;28:533–539. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199610000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha HR, Stieger B, Grassi G, Altorfer HR, Follath F. Structure–effect relationships of amiodarone analogues on the inhibition of thyroxine deiodination. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;55:807–814. doi: 10.1007/s002280050701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harjai KJ, Licata AA. Effects of amiodarone on thyroid function. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:63–73. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-1-199701010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostetler KY, Giordano JR, Jellison EJ. In vitro inhibition of lysosomal phospholipase A1 of rat lung by amiodarone and desethylamiodarone. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;959:316–321. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(88)90205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostetler KY, Reasor MJ, Walker ER, Yazaki PJ, Frazee BW. Role of phospholipase A inhibition in amiodarone pulmonary toxicity in rats. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;875:400–405. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(86)90192-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessurun GA, Boersma WG, Crijns HJ. Amiodarone-induced pulmonary toxicity. Predisposing factors, clinical symptoms and treatment. Drug Saf. 1998;18:339–344. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199818050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann AM, Krise JP. Lysosomal sequestration of amine-containing drugs: analysis and therapeutic implications. J Pharm Sci. 2007;96:729–746. doi: 10.1002/jps.20792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann P, Torok M, Hanni A, Roberts P, Gasser R, Krahenbuhl S. Mechanisms of benzarone and benzbromarone-induced hepatic toxicity. Hepatology. 2005;41:925–935. doi: 10.1002/hep.20634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann P, Torok M, Zahno A, Waldhauser KM, Brecht K, Krahenbuhl S. Toxicity of statins on rat skeletal muscle mitochondria. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:2415–2425. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6235-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krahenbuhl S, Brandner S, Kleinle S, Liechti S, Straumann D. Mitochondrial diseases represent a risk factor for valproate-induced fulminant liver failure. Liver. 2000;20:346–348. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2000.020004346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalevee N, Nargeot J, Barrere-Lemaire S, Gautier P, Richard S. Effects of amiodarone and dronedarone on voltage-dependent sodium current in human cardiomyocytes. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14:885–890. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.03064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JH, Mullick F, Ishak KG, Ranard RC, Ragsdale B, Perse RM, et al. Histopathologic analysis of suspected amiodarone hepatotoxicity. Hum Pathol. 1990;21:59–67. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(90)90076-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JH, Ranard RC, Caruso A, Jackson LK, Mullick F, Ishak KG, et al. Amiodarone hepatotoxicity: prevalence and clinicopathologic correlations among 104 patients. Hepatology. 1989;9:679–685. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840090504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lullmann H, Lullmann-Rauch R, Wassermann O. Drug-induced phospholipidoses. II. Tissue distribution of the amphiphilic drug chlorphentermine. CRC Crit Rev Toxicol. 1975;4:185–218. doi: 10.1080/10408447509164014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin WJ, II, Rosenow EC., III Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity. Recognition and pathogenesis (Part 2) Chest. 1988a;93:1242–1248. doi: 10.1378/chest.93.6.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin WJ, II, Rosenow EC., III Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity. Recognition and pathogenesis (Part I) Chest. 1988b;93:1067–1075. doi: 10.1378/chest.93.5.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason JW. Amiodarone. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:455–466. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198702193160807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morais-Cabral JH, Zhou Y, MacKinnon R. Energetic optimization of ion conduction rate by the K+ selectivity filter. Nature. 2001;414:37–42. doi: 10.1038/35102000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse RM, Valenzuela GA, Greenwald TP, Eulie PJ, Wesley RC, McCallum RW. Amiodarone-induced liver toxicity. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109:838–840. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-10-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien J, Wilson I, Orton T, Pognan F. Investigation of the Alamar Blue (resazurin) fluorescent dye for the assessment of mammalian cell cytotoxicity. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:5421–5426. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitcher WD. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity. Am J Med Sci. 1992;303:206–212. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199203000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak PT. Clinical organ toxicity of antiarrhythmic compounds: ocular and pulmonary manifestations. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84:37R–45R. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00700-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh BN. Antiarrhythmic actions of amiodarone: a profile of a paradoxical agent. Am J Cardiol. 1996;78:41–53. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaniol M, Bracher R, Ha HR, Follath F, Krahenbuhl S. Toxicity of amiodarone and amiodarone analogues on isolated rat liver mitochondria. J Hepatol. 2001;35:628–636. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldhauser KM, Torok M, Ha HR, Thomet U, Konrad D, Brecht K, et al. Hepatocellular toxicity and pharmacological effect of amiodarone and amiodarone derivatives. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:1413–1423. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.108993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda SU, Sausville EA, Hutchins JB, Kennedy T, Woosley RL. Amiodarone-induced lymphocyte toxicity and mitochondrial function. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1996;28:94–100. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199607000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Morais-Cabral JH, Kaufman A, MacKinnon R. Chemistry of ion coordination and hydration revealed by a K+ channel-Fab complex at 2.0 Å resolution. Nature. 2001;414:43–48. doi: 10.1038/35102009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]