Abstract

Summary: Profile Comparer (PRC) is a stand-alone program for scoring and aligning profile hidden Markov models (HMMs) of protein families. PRC can read models produced by SAM and HMMER, two popular profile HMM packages, as well as PSI-BLAST checkpoint files. This application note provides a brief description of the profile–profile algorithm used by PRC.

Availability: The C source code licensed under the GNU General Public Licence and Linux and Mac OS X binaries can be downloaded from http://supfam.org/PRC.

Contact: martin.madera@gmail.com

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Profile Comparer (PRC) is a program for scoring and aligning a profile hidden Markov model (HMM) of a protein family against other profile HMMs.

Profiles are tables that give a score for a particular amino acid to be found at a particular position in an alignment of a protein family. The best known profile method is probably PSI-BLAST (Altschul et al., 1997). Profile HMMs are similar to profiles, but replace scores with probabilities, and introduce additional probabilities for insertions and deletions at each position in the profile (Durbin et al., 1998; Eddy, 1998). All probabilities are placed within a single statistical framework, an HMM. In this note, we shall count profile HMMs among profile methods.

It is now well established that profile–profile methods detect more distant homologies than profile–sequence methods, which in turn are more powerful than sequence–sequence methods (see e.g. Sadreyev and Grishin, 2008; Soding, 2005). Profile–profile methods also generate the most accurate alignments; in fact, profile–profile methods were first used in progressive multiple sequence alignment and only later for homology recognition.

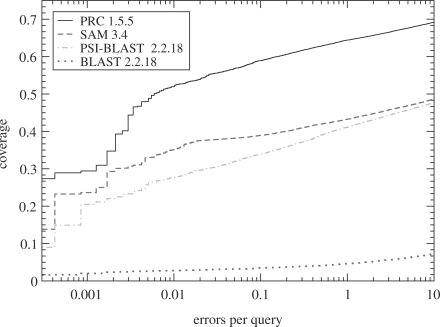

Out of profile–sequence methods, the SAM and HMMER profile HMM programs (Eddy, 1998; Hughey and Krogh, 1996) are believed to be the best (Fig. 1). In addition to insertion and deletion probabilities that vary along the profile, the improvement over, e.g. PSI-BLAST comes from a number of other innovations, including use of the forward algorithm instead of Viterbi (Durbin et al., 1998) and a better algorithm for estimating a profile from a given alignment.

Fig. 1.

A SCOP domain benchmark (Madera and Gough, 2002) of PRC, illustrating the improvement over standard methods. The SCOP seed sequences were filtered to <25% sequence identity. PRC and SAM (Hughey and Krogh, 1996) used SUPERFAMILY profile HMMs (Gough et al., 2001). PSI-BLAST (Altschul et al., 1997) checkpoint files used in the benchmark were derived from SUPERFAMILY profile HMMs and use identical probabilities for the profile part. For a comparison of PRC to competing profile–profile methods, the reader is referred to Soding (2006) and Sadreyev and Grishin (2008).

The goal of PRC is to apply lessons learned from development of SAM and HMMER to the profile–profile case. PRC was first publicly released in 2002 and has been used by Pfam since 2005. Recently PRC has performed well in benchmarks (Sadreyev and Grishin, 2008; Soding, 2006) carried out by the authors of the two main alternative profile–profile methods, COMPASS (Sadreyev and Grishin, 2008) and HHsearch (Soding, 2005). Here, we provide an overview of the PRC algorithm (version 1.5.5) and explain how to use the program.

2 THE PRC ALGORITHM

When scoring a profile HMM against a library of profile HMMs, PRC reports E-values, which give an estimate of how significant the matches are. In order to calculate E-values, PRC first calculates three other scores: co-emission, simple and reverse. Each score builds upon the previous one, until finally reverse scores are converted into E-values.

The co-emission score Sco-em is a generalization of the log-odds score Slog-odds calculated by SAM and HMMER,

| (1) |

to the HMM–HMM case:

| (2) |

The sum is over all possible amino acid sequences σ, and the probability P(σ|HMM) that the profile HMM emits a sequence σ is calculated using the forward algorithm (Durbin et al., 1998). When one of the HMMs is extremely ‘narrow’, e.g. it only emits a single sequence τ with a non-zero probability (P(σ|HMM) = 1 if σ = τ, 0 otherwise), the co-emission score tends to the profile HMM log-odds score for τ. The null model emits random sequences with background amino acid frequencies and a geometric distribution of lengths.

The simple score Ssimple is the same as the co-emission score Sco-em, but both profile HMMs are restricted to regions of significant similarity. The regions are found by an iterative procedure that picks a new end point as the maximum of the forward score in the dynamic programming matrix, and a start point as the maximum of the backward score.

The reverse score Srev for two profile HMMs 1 and 2 is defined as

| (3) |

where the reverse HMM is defined as follows:

| (4) |

Here, rev is a reverse operator that maps residue or model segment i (1 ≤i≤L) onto residue L−i+1. This is a generalization of the reverse sequence null model used by SAM (Karplus et al., 2005).

Finally, for library runs the reverse score Srev is turned into an E-value by fitting the following function to the observed distribution of reverse scores:

| (5) |

The E-value E is the expected number of random matches with a reverse score better than x, and nunrel is the number of profile HMMs in the library that are unrelated to the query. The formula is a slight generalization of the function used by SAM (Karplus et al., 2005). Optimal values of the two parameters λ and κ for each run are found using a censored Maximum Likelihood fitting procedure.

HMM–HMM alignments are computed by finding the Viterbi path that maximizes the sum of forward–backward odds scores (Durbin et al., 1998).

3 USING PRC

PRC can read SAM3 (ASCII and binary) and HMMER2 model files, and PSI-BLAST checkpoint files. The same internal profile HMM is used for scoring all three. For PSI-BLAST checkpoint files, the profile part is taken from the checkpoint file and the insertion and deletion probabilities are set to default values, constant throughout the model. For best performance, users should build a full profile HMM using the SAM w0.5 script.

For accurate E-values, the library should contain at least 1000 profile HMMs. For libraries of sufficient size, E <0.003 can be taken as indicative of homology and E < 10−5 as a strong match. When a large library is not available, Equation (5) with λ = 0.8, κ = 0 can be used as a conservative guide.

Starting with version 1.5.5, the PRC source code also includes a simple Perl script, merge_aligns.pl. Given two HMM–sequence alignments in the SAM a2m format, and a PRC alignment between the two HMMs, the script will output a pairwise alignment between the two sequences. Users who would like to visualize their HMM–HMM alignments are referred to the pairwise HMM logos server (Schuster-Bockler and Bateman, 2005).

Funding

M.M.'s Internal Graduate Studentship from Trinity College, Cambridge, UK; the UK Medical Research Council and the Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge, UK (Cyrus Chothia's group); the European Bioinformatics Institute (Nick Goldman's group); Kevin Karplus's National Institutes of Health grant R01 GM068570; Julian Gough's European Union Framework Programme 7 IMPACT grant.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Altschul SF, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin R, et al. Biological Sequence Analysis: Probabilistic Models of Proteins and Nucleic Acids. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Eddy SR. Profile hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:755–763. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough J, et al. Assignment of homology to genome sequences using a library of hidden Markov models that represent all proteins of known structure. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;313:903–919. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughey R, Krogh A. Hidden Markov models for sequence analysis: extension and analysis of the basic method. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1996;12:95–107. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karplus K, et al. Calibrating E-values for hidden Markov models using reverse-sequence null models. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:4107–4115. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madera M, Gough J. A comparison of profile hidden Markov model procedures for remote homology detection. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:4321–4328. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadreyev RI, Grishin NV. Accurate statistical model of comparison between multiple sequence alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn065. [doi:10.1093/nar/gkn065, Epub ahead of print, February 19, 2008] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster-Bockler B, Bateman A. Visualizing profile-profile alignment: pairwise HMM logos. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2912–2913. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soding J. Protein homology detection by HMM-HMM comparison. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:951–960. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soding J. [[Last accessed date, October 8, 2008]];2006 Available at http://toolkit.tuebingen.mpg.de/hhpred/help_ov.