Abstract

Astrocytes remove glutamate from the synaptic cleft via specific transporters, and impaired glutamate reuptake may promote excitotoxic neuronal injury. In a model of viral encephalomyelitis caused by neuroadapted Sindbis virus (NSV), mice develop acute paralysis and spinal motor neuron degeneration inhibited by the AMPA receptor antagonist, NBQX. To investigate disrupted glutamate homeostasis in the spinal cord, expression of the main astroglial glutamate transporter, GLT-1, was examined. GLT-1 levels declined in the spinal cord during acute infection while GFAP expression was preserved. There was simultaneous production of inflammatory cytokines at this site, and susceptible animals treated with drugs that blocked IL-1β release also limited paralysis and prevented the loss of GLT-1 expression. Conversely, infection of resistant mice that develop mild paralysis following NSV challenge showed higher baseline GLT-1 levels as well as lower production of IL-1β and relatively preserved GLT-1 expression in the spinal cord compared to susceptible hosts. Finally, spinal cord GLT-1 expression was largely maintained following infection of IL-1β-deficient animals. Together, these data show that IL-1β inhibits astrocyte glutamate transport in the spinal cord during viral encephalomyelitis. They provide one of the strongest in vivo links between innate immune responses and the development of excitotoxicity demonstrated to date.

Keywords: glutamate transporters, interleukin-1β, viral encephalomyelitis, motor neuron, excitotoxicity

Introduction

Glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity has been implicated in the pathogenesis of both acute and chronic neurodegeneration, and defects in extracellular glutamate reuptake are considered important to the evolution of disorders such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Alzheimer's disease (AD), and stroke (Rothstein et al. 1992; Rothstein et al. 1995; Masliah et al.1996; Li et al. 1997; Mallolas et al. 2006). More recently, loss of the excitatory amino acid transporters (EAATs) has also been observed in lesions from patients with infectious and inflammatory disorders of the CNS known to have a neurodegenerative component (Werner et al. 2001; Wang et al. 2004; Vercellino et al. 2007), thus broadening the potential clinical relevance of impaired glutamate reuptake. Not only have these recent data brought more focus onto the general importance of neuroinflammation in the pathogenesis of diseases such as ALS and AD (Moisse and Strong 2006; Wyss-Coray 2006), but they have also stimulated further investigation into the specific roles played by host immune responses in controlling extracellular glutamate removal (Tilleux and Hermans 2007). Microglia, in particular, are implicated in the production of inflammatory mediators that impair glutamate transport (Tilleux and Hermans 2007), and drugs that inhibit microglial activation have now been touted as a practical strategy to treat various neurodegenerative disorders by dampening this effect (McCarty 2006). Still, microglia may also serve a neuroprotective role, particularly in the setting of acute brain injury (Simard and Rivest 2007). Thus, the in vivo relationship between innate immune responses and neurodegeneration via excitotoxicity pathways requires further study.

While EAATs have been identified on the plasma membranes of both glia and neurons, astrocytes dominate the extracellular glutamate reuptake process (Anderson and Swanson 2000). In rodents, glutamate transporter-1 (GLT-1, also known as EAAT2 in humans) is the main astrocytic EAAT and is expressed widely throughout the CNS; it may account for more than 90% of all CNS glutamate transport (Rothstein et al. 1996; Tanaka et al. 1997). Expression and function of GLT-1 by primary astrocytes can be suppressed in vitro following exposure to the inflammatory cytokines, interleukin (IL)-1β and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (Ye and Sontheimer 1996; Szymocha et al. 2000; Wang et al. 2003; Korn et al. 2005), yet inflammatory regulators of this protein in vivo remain poorly defined. Nevertheless, GLT-1 expression is diminished within inflammatory CNS lesions of both animals and humans (Ohgoh et al. 2002; Vercellino et al. 2007), even if the mediators involved and the functional consequences of this change remain unclear. An improved understanding of the inflammatory regulators of this protein directly within the CNS might eventually reveal unique pharmacological strategies that could reduce excitotoxicity in these disorders.

Alphaviruses are important causes of acute and often fatal encephalomyelitis in humans. One of these pathogens, neuroadapted Sindbis virus (NSV), causes acute encephalomyelitis in mice and closely reproduces many features of the related human infections. Spread of NSV from neurons of the brain to the spinal cord typically results in hind limb paralysis in susceptible hosts (Jackson et al. 1987), although a few inbred strains of mice are more resistant to this phase of disease (Thach et al. 2000). Glutamate excitotoxicity has recently been identified as an important mediator of neuronal injury in the spinal cord during NSV infection (Darman et al. 2004; Nargi-Aizenman et al. 2004), and the fate of spinal motor neurons determines the severity of paralysis among infected mice. Host immune responses also contribute to the development of this paralysis (Liang et al. 1999; Irani and Prow 2007), leading us to investigate their connection to excitotoxic pathways. Here, we report that the inflammatory cytokine, IL-1β, is responsible for the loss of spinal cord GLT-1 expression during infection. This results in excitotoxic spinal motor neuron damage and the development of hind limb paralysis. We propose that the link between CNS IL-1β production and reduced GLT-1 expression could potentially explain the occurrence of neuronal injury during other neuroinflammatory disorders as well.

Materials and Methods

Animal manipulations

All animal procedures had received prior approval from our institutional animal care and use committee and were performed under isoflurane anesthesia (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL). Five week-old C57BL/6 and BALB/cBy mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Animals homozygous for IL-1β gene deficiency (IL-1β−/− mice) as well as age- and strain-matched, but non-littermate, control animals (IL-1β+/+ mice) were purchased directly from Taconic (Hudson, NY). To induce encephalomyelitis, 1000 plaque-forming units of NSV suspended in 20μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were inoculated directly into the right cerebral hemisphere of each animal. Mice were monitored daily for signs of disease and for survival in accordance with approved animal protocols. Twenty animals per group were used for all experiments unless otherwise noted. For those experiments where spinal cord tissue samples were not being collected for ex vivo analysis, each live animal was scored daily by a blinded examiner into one of the following categories: 0) normal, 1) mild paralysis (some weakness of one or both hind limbs), 2) moderate paralysis (weakness of one hind limb, paralysis of the other hind limb), or 3) severe paralysis (complete paralysis of both hind limbs). Some animals received intraperitoneal treatments with the following agents (obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) according to the following schedules: 1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-6-nitro-2,3-dioxobenzo(f)quinoxaline (NBQX, 30 mg/kg twice daily), MK-801 (1 mg/kg/day), naloxone hydrochloride (50 mg/kg/day), minocycline (25 mg/kg twice daily), or a saline vehicle control starting on the day after viral challenge.

Immunoblotting of tissue extracts

Animals designated for immunoblotting or tissue cytokine assays were perfused with chilled PBS via a transcardial approach. To prepare tissue samples for immunoblots, lumbar spinal cords were dissected and sonicated in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, 1% sodium sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, pH 7.6) after the addition of a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). Total protein concentrations were determined using a commercial protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). A total of 5μg of each sample was separated on 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Bioexpress, Kaysville, UT). Separated proteins were then transferred to Hybond-C extra nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) using an electrophoretic transfer system (Bio-Rad) in 20% methanol transfer buffer. Membranes were blocked for 1 hour in 5% non-fat skim milk diluted in PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20, and incubated overnight in primary antibody diluted in 1% non-fat skim milk in PBS. Primary antibodies included anti-GLT-1 (Sigma-Aldrich, 1:200), anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, Chemicon, Temecula, CA, 1:1,000), and anti-actin (Chemicon, 1:10,000). After washing, membranes were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Amersham, 1:5,000), washed, developed with Supersignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL), and visualized using a Fuji Luminsecent Image Analyzer (Fuji Photo Film Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Each GLT-1 and GFAP blot was stripped and reprobed for actin expression. The intensity of each band was determined using ImageJ software, version (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), and GLT-1 or GFAP levels were normalized to actin expression in each lane. In most cases, protein expression levels in infected tissue samples were then normalized to levels present in uninfected controls (set at 100%). Triplicate samples at each time point were analyzed, and the mean ± SEM of relative expression levels or percent of control levels in uninfected tissue are shown.

Tissue cytokine assays

IL-1β and TNF-α levels in spinal cord lysates made from tissues derived from PBS-perfused animals were determined using ELISA kits according to the manufacturer's instructions (Biosource, Camarillo, CA). Each lysate was made in PBS and standardized such that 50μg of total spinal cord protein was applied to each ELISA plate. Cytokine concentrations in each test sample were calculated based on direct comparison to known concentrations of a standard provided with each assay kit. Triplicate samples at each time point and under each experimental condition were analyzed; the mean ± SEM of concentrations per μg of total spinal cord protein are shown.

Histology

Animals designated for histological analyses were sequentially perfused with chilled PBS and 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS via a transcardial approach. Tissues were then post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C, after which they were embedded in paraffin for sectioning. All spinal cord sections were taken from the same level of the lumbar spinal cord to ensure uniform comparisons between animals. To assess the fate of spinal motor neurons, serial sections were prepared and every 20th section was collected onto glass slides for staining with hematoxylin and eosin. Motor neurons were defined as cells present in the spinal grey matter, ventral to the central canal, and having a cell body >25μm in diameter. A blinded examiner counted these cells under 20x magnification. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of the total number of motor neurons per section; 10 sections from each animal were counted, and 3−5 animals were analyzed per experimental group.

Immunohistochemistry

For immunoperoxidase staining, spinal cord sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, treated with 1% hydrogen peroxide in ice-cold methanol for 30 minutes to block endogenous peroxidase, and rinsed in PBS. Sections were blocked with 1% normal serum matching the animal in which the secondary antibody was raised for 1 hour at room temperature. Primary antibody was applied to each section, diluted in PBS containing 0.5% non-fat skim milk plus 1% normal serum overnight at 4°C. The following primary antibodies were utilized: anti-GFAP (Chemicon, 1:200) or anti-GLT-1 (Sigma-Aldrich, 1:80). Secondary antibodies were conjugated to biotin and used at 1:200 (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Following several more washes to remove all unbound secondary antibody, sections were sequentially incubated with avidin-DH-biotin complex solution (Vector) in PBS, and then treated with 0.5 mg/ml diaminobenzidine (Polysciences, Warrington, PA) containing 0.01% hydrogen peroxide. All sections were counterstained with hematoxylin (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ), dehydrated in graded alcohol washes, mounted with glass coverslips in Permount (Fisher), and directly visualized using light microscopy for photography using Spot advanced software, version 4.0.1 (Diagnostic Instrument Inc, Sterling Heights, MI).

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism, version 4.02, was used for all statistical analyses (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA). The significance of paralysis or survival differences between experimental groups was determined by Kaplan-Meier analysis. The Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to analyze differences between groups at individual time points, and Friedman's nonparametric repeated measures comparison was used to analyze differences across time within an individual group. Because of the nonparametric nature of the data, nonparametric equivalent tests of ANOVA and repeated measures ANOVA were used to increase the robustness of the results. Significance in all experiments was assessed at the 0.05 level.

Results

AMPA receptor blockade inhibits paralysis and promotes motor neuron survival

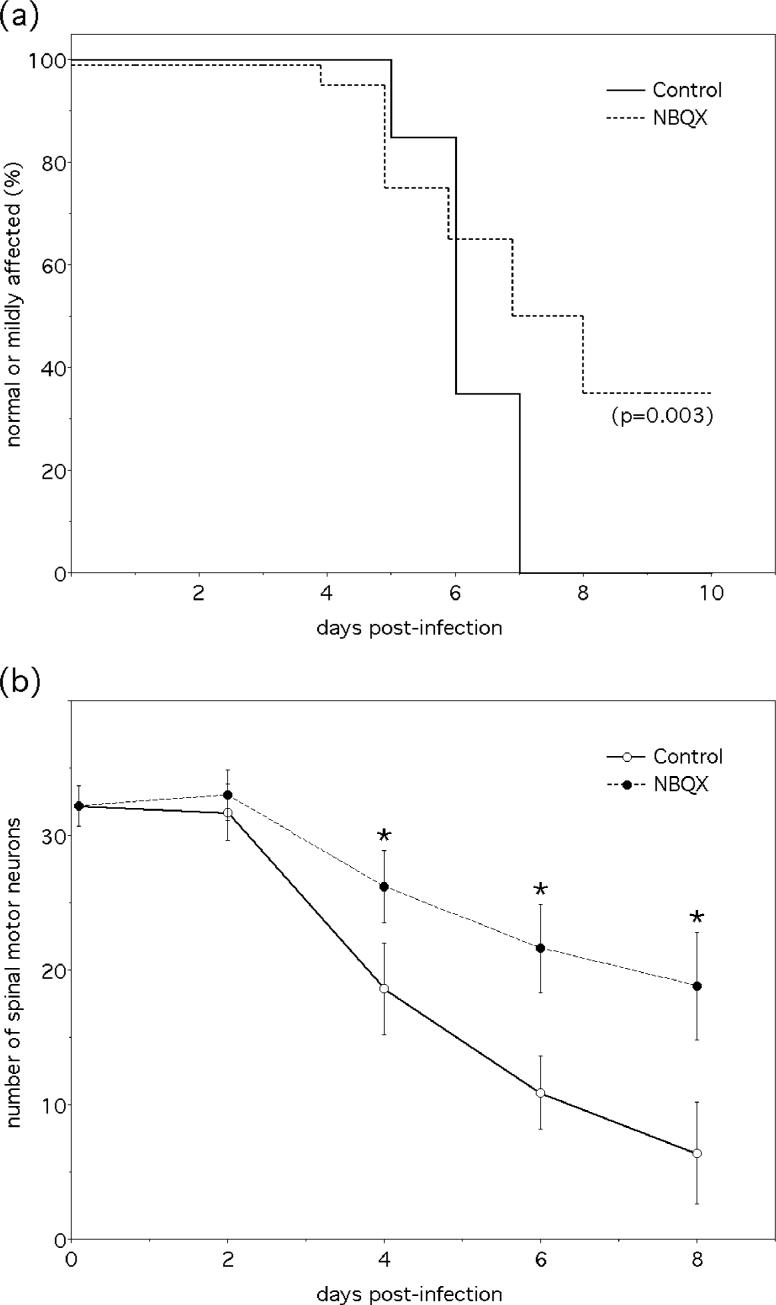

Glutamate excitotoxicity has recently been identified as an important mediator of NSV-induced neuronal injury both in vitro and in vivo (Nargi-Aizenman and Griffin 2001; Darman et al. 2004; Nargi-Aizenman et al. 2004). To determine the role of specific glutamate receptor subtypes in the development of paralysis and motor neuron degeneration following NSV infection in vivo, animals were treated with different glutamate receptor antagonists and clinical and histological parameters were followed over time. The prototype NMDA receptor blocking drug, MK-801, had no effect on either the course of disease or on the degeneration of spinal motor neurons at the maximum tolerated dose (data not shown). Conversely, the alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionate (AMPA) receptor antagonist, NBQX, inhibited the progression of NSV-infected animals to moderate or severe levels of paralysis (Fig. 1a), and prevented the destruction of motor neurons in the lumbar spinal cord that occurs with this disease (Fig. 1b). Drug treatment also significantly enhanced overall disease survival (Fig. 1 legend), although such a difference is not likely the direct result of any effect on lumbar spinal motor neurons that are the focus of the present study. Our findings confirm the importance of glutamate excitotoxicity in the spinal cord during alphavirus encephalomyelitis and they justify further investigation into the mechanisms that underlie activation of this cell death pathway at this tissue site.

Figure 1.

Blockade of the AMPA subtype of glutamate receptors limits paralysis and spinal motor neuron degeneration in mice with NSV encephalomyelitis. (a) Parallel groups of animals were challenged with NSV and treated with the AMPA receptor antagonist, NBQX (30 mg/kg twice daily), or a vehicle control. A blinded examiner scored paralysis on a daily basis among surviving animals using a standardized scale; the proportion of mice with either normal findings or mild paralysis is shown. Drug treatment also reduced mortality in these animals (45% in the NBQX group, 100% in the control group, p=0.0004), demonstrating that the disease severity differences shown are not due to a subtle shift between mild and moderate paralysis scores. The significance of paralysis and survival differences was determined by Kaplan-Meier analysis. (b) This same NBQX treatment regimen enhanced the survival of lumbar motor neurons in NSV-infected animals. Mean ± SEM of motor neuron counts in lumbar spinal cord tissue sections are shown (*p< 0.05 favoring drug-treated animals compared to vehicle-treated controls at each time point was determined via the Kruskal-Wallis test).

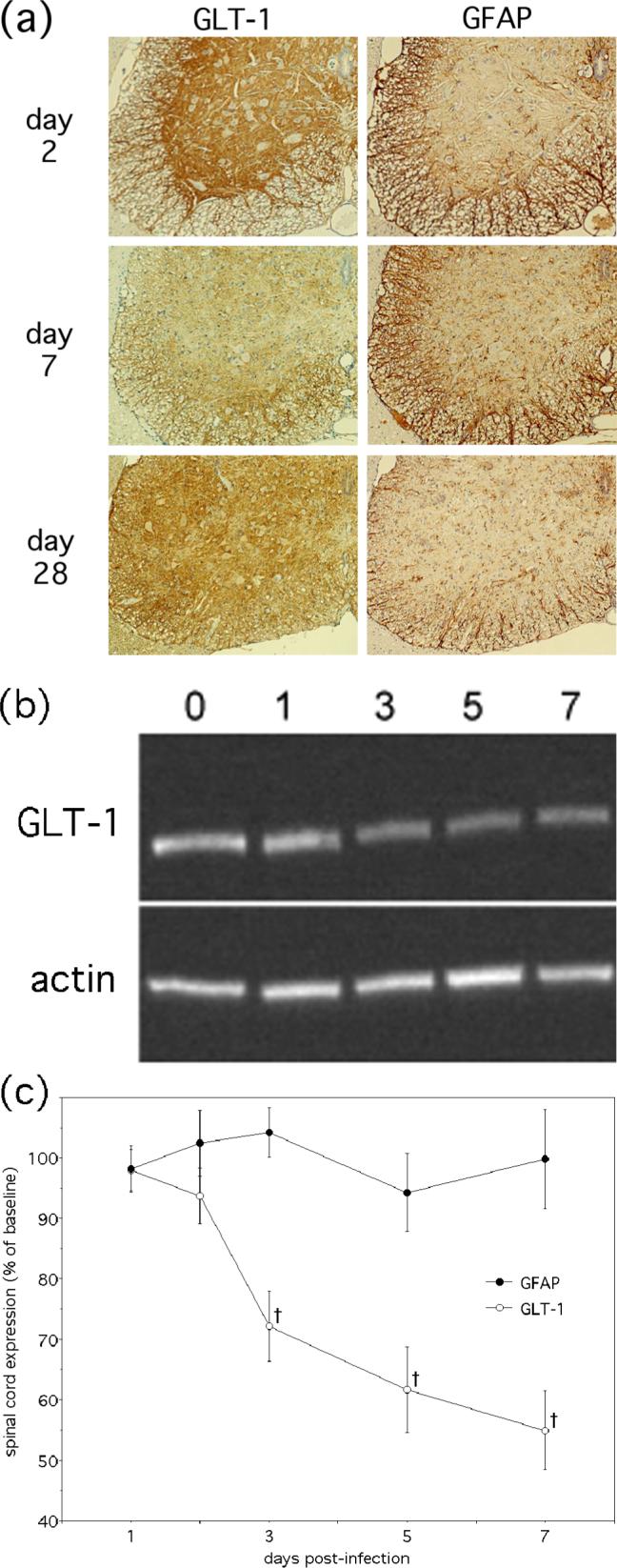

Selective loss of GLT-1 in the lumbar spinal cord

Removal of extracellular glutamate is largely dependent on cellular reuptake by EAATs, and GLT-1, a protein expressed primarily on astrocytes, is the dominant EAAT found in the spinal cord (Rothstein et al. 1996; Anderson and Swanson 2000). To determine whether disrupted glutamate homeostasis in the spinal cords of NSV-infected mice might be the result of impaired transmitter reuptake, GLT-1 expression was localized by immunohistochemical staining and quantified by Western blot. Analysis of lumbar spinal cord tissue sections showed a focal loss of GLT-1 immunoreactivity directly within the ventral grey matter where motor neuron cell bodies reside (Fig. 2a). There was no associated loss of GFAP staining to suggest a significant dropout of astrocytes in these same regions, and tissue expression of GLT-1 recovered at late stages of disease even when there was no return of hind limb motor function in the few surviving animals (Fig. 2a, paralysis data not shown). Quantification of spinal cord GLT-1 and GFAP expression by Western blotting showed that transporter levels began to decline immediately prior to the onset of paralysis and progressed over the course of the acute disease while GFAP levels remained stable (Fig. 2c). Similar analyses also showed that spinal cord GLT-1 levels declined in NBQX-treated animals, demonstrating that transporter dysregulation precedes lumbar motor neuron excitotoxicity (data not shown). Taken together, these data suggest that an acquired and reversible defect in glutamate reuptake by astrocytes locally within the lumbar spinal cord may be responsible for the excitotoxic damage of adjacent motor neuron cell bodies, thus causing the hind limb paralysis that develops following NSV infection. Although dropout of some astrocytes cannot be excluded, it seems unlikely that a focal loss of these cells in spinal grey matter can account for the observed effect on transporter expression since GFAP levels were preserved throughout disease and because GLT-1 immunoreactivity did eventually recover.

Figure 2.

Spinal cord expression of the main astroglial glutamate transporter, GLT-1, declines over the course of acute NSV encephalomyelitis. (a) Immunohistochemical staining (brown) shows focal loss of GLT-1 signal in the ventral grey matter of the lumbar spinal cord between early (day 2) and peak (day 6) infection. Expression returns to baseline after acute infection has subsided (day 28), despite continued paralysis in the few surviving animals at this late stage of disease (not shown). GFAP expression is not significantly altered in adjacent tissue sections, indicating the continued presence of astrocytes in spinal grey matter throughout infection. (b) A representative Western blot shows that total lumbar spinal cord GLT-1 levels decline over the acute stages of NSV infection while actin expression is preserved. (c) Quantification (mean ± SEM) of GLT-1 and GFAP levels in lumbar spinal cord normalized to actin and then to levels found in uninfected control tissue shows the percent change of each protein over the course of acute stages of disease († p< 0.05 indicating significantly reduced levels compared to those detected in uninfected control animals as determined by Friedman's nonparametric test).

Relationship between inflammatory cytokines and GLT-1 expression in the spinal cord

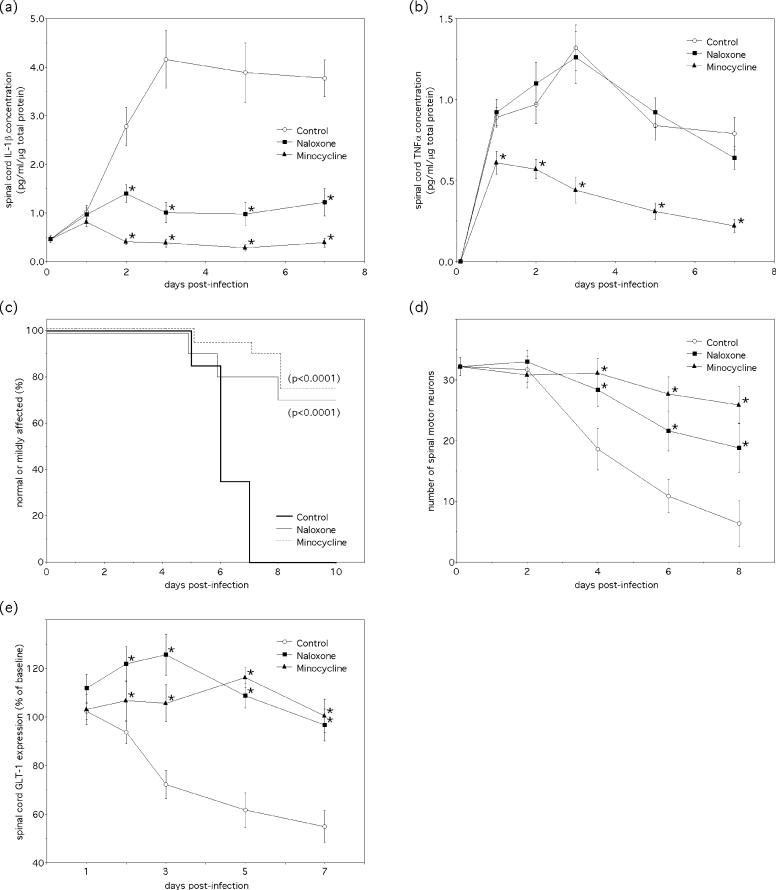

Further inspection of our immunostained spinal cord tissue sections showed that loss of GLT-1 expression was most pronounced in areas of robust tissue inflammation (Fig. 2a) and microglial activation (data not shown). Since the inflammatory cytokines, IL-1β and TNF-α, have both been shown to suppress EAAT expression and glutamate reuptake by astrocytes in vitro (Ye and Sontheimer 1996; Szymocha et al. 2000; Wang et al. 2003; Korn et al. 2005), the relationship between local tissue cytokine production, paralysis, motor neuron degeneration, and GLT-1 expression was investigated in the spinal cords of NSV-infected animals. Analysis of tissue homogenates showed a rapid induction of both IL-1β and TNF-α in the spinal cord following infection (Fig. 3a,b), and treatment of animals with two unrelated drugs, minocycline and naloxone, was effective at blunting the IL-1β response in particular (Fig. 3a). Both drugs also mitigated the severity of NSV-induced paralysis (Fig. 3c), the degeneration of spinal motor neurons (Fig. 3d), and the loss of spinal cord GLT-1 expression that ensued following infection (Fig. 3e). These findings highlight a proposed relationship between innate immune responses elicited in the spinal cord by NSV infection and the loss of local GLT-1 expression leading to excitotoxic motor neuron injury.

Figure 3.

Levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-1β and TNF-α, increase in the spinal cord in parallel to GLT-1 loss and just prior to the development of paralysis, while drugs that block induction of IL-1β also limit paralysis, protect motor neurons, and mitigate the decline in GLT-1 expression at this site. (a,b) Spinal cord levels of IL-1β and TNF-α increase during acute NSV infection, and treatment of animals with either minocycline (25 mg/kg twice daily) or naloxone (50 mg/kg/day) blunts the IL-1β response. Mean ± SEM of cytokine levels in lumbar spinal cord tissue homogenates at each time point are shown (*p< 0.05 indicates significant reduction compared to untreated control animals at each time point as determined by the Kruskal-Wallis test). (c) Both drug treatment regimens reduce the development and severity of NSV-induced hind limb paralysis (significance determined by Kaplan-Meier analysis), (d) and both prevent spinal motor neuron degeneration compared to untreated controls (control data generated separately and is the same as presented in Fig. 1b). Mortality was 100% in the control group shown in (c). Mean ± SEM of motor neuron counts in lumbar spinal cord tissue sections are shown (*p< 0.05 indicates significantly improved cell survival compared to untreated controls at each time point as determined by the Kruskal-Wallis test; control data is the same as presented in Fig. 1b). (e) Both drugs also prevent the decline in spinal cord GLT-1 levels during NSV infection as measured by Western blot. Mean ± SEM of the percent GLT-1 expression normalized to actin and then to levels found in uninfected control spinal cords are shown (*p< 0.05 indicates significantly higher levels compared to untreated control animals at each time point as determined by the Kruskal-Wallis test; control data generated separately and is the same as presented in Fig. 2c).

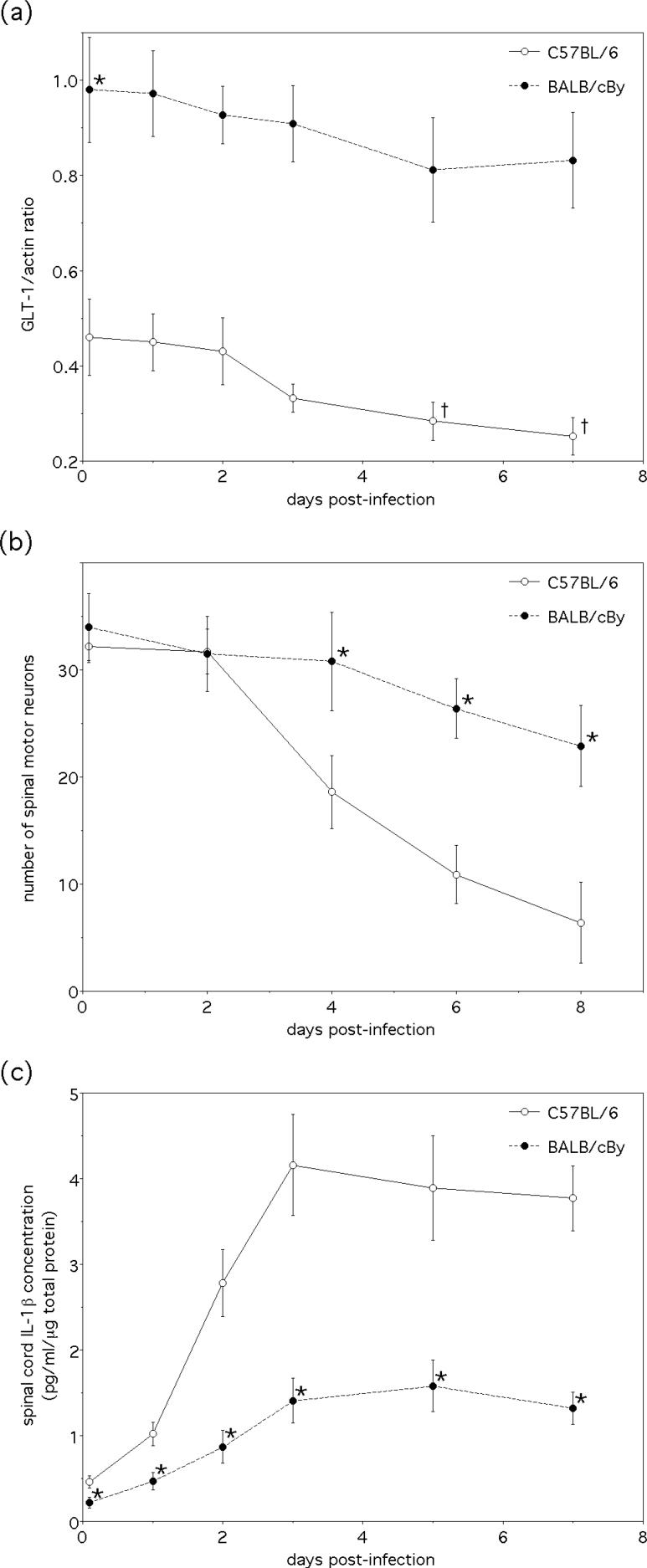

Cytokine and GLT-1 levels in the spinal cords of paralysis-resistant animals

The BALB/cBy substrain of BALB/c mice has previously been shown to be resistant to NSV-induced paralysis through a mechanism not related to either altered virus tropism or impaired virus replication in the spinal cord (Thach et al. 2000). When spinal cord tissues from this host strain were directly compared to samples obtained from highly susceptible C57BL/6 mice, significantly higher baseline levels of GLT-1 expression were observed (Fig. 4a). When both hosts were challenged with NSV, not only were spinal motor neurons more likely to survive in the resistant hosts (Fig. 4b), but also there was significantly less IL-1β induced in the spinal cord (Fig. 4c) and the expected decline of spinal cord GLT-1 levels was blunted compared to the susceptible animals (Fig. 4a). These data further enhance the proposed link between local IL-1β induction and loss of GLT-1 expression in the spinal cord during acute NSV encephalomyelitis. They also highlight an interesting host strain difference in the constitutive expression of this glutamate transporter in the spinal cord that may also contribute to paralysis resistance.

Figure 4.

Comparison of GLT-1 expression, motor neuron survival, and IL-1β levels in the spinal cords of C57BL/6 (paralysis-susceptible) and BALB/cBy (paralysis-resistant) mice following NSV infection. (a) Spinal cord GLT-1 levels normalized to actin are significantly higher at baseline in BALB/cBy mice than C57BL/6 animals (*p<0.05 via the Kruskal-Wallis test). While spinal cord GLT-1 expression declines in both host strains over the course of acute NSV infection, the relative drop is greater in C57BL/6 mice (†p<0.05 indicating significant reduction compared to levels in uninfected control animals as determined via Friedman's nonparametric test). (b) Spinal motor neurons survive to a much greater degree in BALB/cBy mice following NSV challenge. Mean ± SEM of motor neuron counts in lumbar spinal cord tissue sections are shown (*p< 0.05 favoring the BALB/cBy mice compared to the C57BL/6 animals at each time point as determined by the Kruskal-Wallis test; data for the C57BL/6 mice generated separately and is the same as presented in Fig. 1b and Fig. 3d). (c) Induction of IL-1β in spinal cord tissue during NSV infection is blunted in BALB/cBy mice. Mean ± SEM of IL-1β levels in lumbar spinal cord tissue homogenates at each time point are shown (*p< 0.05 indicates significant reduction compared to C57BL/6 control animals at each time point as determined by the Kruskal-Wallis test; C57BL/6 data generated separately and is the same as presented in Fig. 3a).

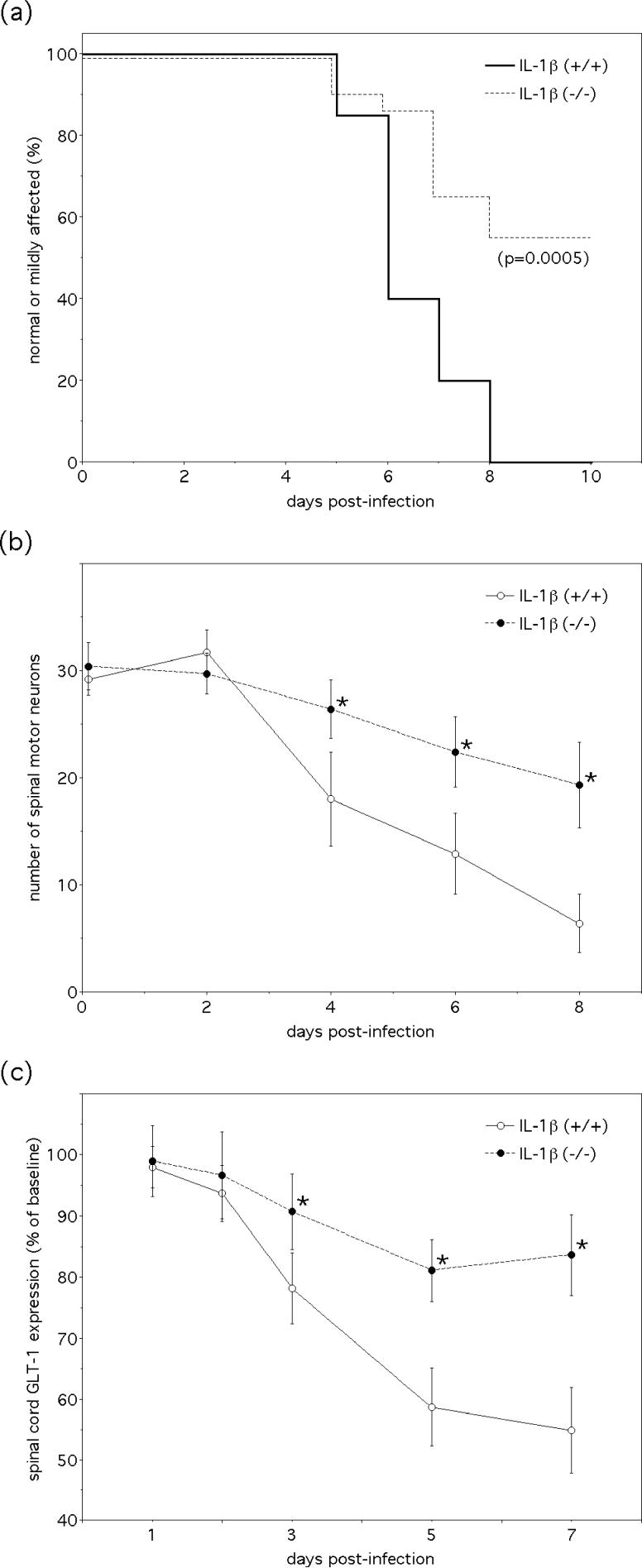

Paralysis and spinal cord GLT-1 levels in IL-1β-deficient animals

Hind limb paralysis is attenuated in IL-1β-deficient (IL-1β−/−) mice following NSV infection, although the mechanisms underlying this altered disease phenotype remain poorly understood (Liang et al. 1999). Because of accumulating evidence linking IL-1β production in the spinal cord with loss of GLT-1 expression during NSV infection, experiments to more directly examine the relationship between these two events were undertaken in IL-1β−/− mice. Not only did we confirm that hind limb paralysis and spinal motor neuron degeneration is attenuated in NSV-infected IL-1β−/− mice compared to IL-1β+/+ controls (Fig. 5a,b), but also that loss of spinal cord GLT-1 expression during infection is highly dependent on the host's capacity to make IL-1β (Fig. 5c). Because infection clearly induces significant IL-1β production in the spinal cord (Fig. 3a), these data demonstrate that local actions of this inflammatory cytokine are responsible for suppressing expression of this glutamate transporter.

Figure 5.

Production of IL-1β in the spinal cord drives the development of hind limb paralysis, motor neuron degeneration, and reduced local GLT-1 expression during NSV encephalomyelitis. (a) Paralysis is less severe in a cohort of IL-1β−/− mice compared to matched IL-1β+/+ controls following virus challenge. IL-1β deficiency also reduces disease mortality (15% in the IL-1β−/−mice, 80% in the IL-1β+/+ controls, p=0.0006), demonstrating that paralysis differences are not just due to a shift between mild and moderate severity scores. The significance of differences in paralysis and survival between the two groups was determined by Kaplan-Meier analysis. (b) Motor neuron survival is enhanced over the course of acute infection in the absence of IL-1β. Mean ± SEM of motor neuron counts in lumbar spinal cord tissue sections are shown (*p< 0.05 favoring the IL-1β−/− mice compared to IL-1β+/+ controls at each time point as determined by the Kruskal-Wallis test). (c) Finally, IL-1β deficiency prevents the decline in spinal cord GLT-1 levels during NSV infection as measured by Western blot. Mean ± SEM of the percent GLT-1 expression normalized to actin and then to levels found in uninfected control spinal cords are shown (*p< 0.05 indicating significantly higher levels in the IL-1β−/− mice compared to IL-1β+/+ controls at each time point as determined by the Kruskal-Wallis test).

Discussion

Increasing evidence supports a link between innate immune responses within the CNS and the development of excitotoxic neuronal injury. Not only may endogenous immune cells such as microglia be direct sources of glutamate (Noda et al. 1999; Takeuchi et al. 2006; Barger et al. 2007), but their various inflammatory products may also alter synaptic glutamate homeostasis in a number of important ways. One such mechanism is by inhibiting extracellular glutamate reuptake, a process normally mediated by the EAATs expressed on a variety of neural cell types. Astrocytes are a major contributor to CNS glutamate reuptake, and by some estimates, GLT-1 controls more than 90% of transmitter clearance (Rothstein et al. 1996; Tanaka et al. 1997; Anderson and Swanson 2000). The effects of inflammatory mediators on EAAT expression and glutamate reuptake by astrocytes have been studied in vitro (Ye and Sontheimer 1996; Szymocha et al. 2000; Miralles et al. 2001; Wang et al. 2003; Korn et al. 2005), although direct proof that such mediators contribute to defects in glutamate reuptake and the development of excitotoxicity in vivo is scarce. Here, we show that production of the inflammatory cytokine, IL-1β, suppresses GLT-1 expression in the spinal cord that, in turn, drives the excitotoxic destruction of spinal motor neurons in an experimental model of alphavirus encephalomyelitis. We propose this finding has potential implications for understanding the pathogenesis of related CNS infectious and inflammatory disorders as well.

Glutamate excitotoxicity has been known for some time to underlie neuronal damage during CNS viral infection (Espey et al. 1998). Its role is perhaps best studied in the NSV model (Nargi-Aizenman and Griffin 2001; Darman et al. 2004; Nargi-Aizenman et al. 2004), even though the molecular mechanisms that trigger this form of injury have until recently remained poorly understood. Expanding evidence suggests that host responses contribute to paralysis and death during NSV infection (Liang et al. 1999; Irani and Prow 2007; Prow and Irani 2007), and we have used both pharmacological and genetic strategies in the present study to implicate the inflammatory cytokine, IL-1β, in mediating excitotoxic spinal motor neuron injury via an induced defect in glutamate reuptake. While some controversy surrounds the mechanisms of action of both minocycline and naloxone as neuroprotectants, emerging evidence suggests that both drugs can target activated microglial cells to achieve this effect (Yong et al. 2004; Qin et al. 2005). Interestingly, naloxone may exert such an effect independent of its actions on classic opioid receptors (Liu and Hong 2003; Qin et al. 2005). As to our genetic approach, some caution must be used in interpreting our results in the IL-1β−/− mice since non-littermate, but otherwise age- and strain-matched, control animals were used. Still, blockade of IL-1 receptors via an exogenous IL-1 receptor antagonist attenuates NSV-induced paralysis (Irani and Prow 2007), and such treatment also mitigates the loss of spinal cord GLT-1 expression (data not shown). Taken together, these findings implicate both IL-1β production and IL-1 receptor signaling as being proximal events in the glutamate transporter effects observed in this model.

Impaired glutamate reuptake due to selective loss of the astroglial glutamate transporter, GLT-1/EAAT2, is likely to be a pathogenic event underlying the degeneration of motor neurons in patients with ALS (Rothstein et al. 1992; Rothstein et al. 1995). Similar glutamate transport defects have also been observed in the spinal cords of transgenic animals carrying a mutant form of superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1/G37R) that models familial ALS (Howland et al. 2002; Warita et al. 2002; Dunlop et al. 2003). Recent studies conducted in these transgenic animals suggest that innate immune responses, many likely arising from activated microglial cells, accelerate the degeneration of spinal motor neurons and the development of overt weakness. Thus, treatment of transgenic SOD1/G37R animals with drugs that inhibit microglial activation delays both the onset and the progression of disease (Zhu et al. 2002). Likewise, animals that carry a mutant SOD1/G37R transgene that can be selectively deleted in microglia have unaffected disease onset but show significantly slower disease progression compared to non-deleted controls (Boillée et al. 2006). Still, the precise mechanisms through which microglia damage motor neurons in these animals are poorly understood, and the molecular connections between microglia and the pathways leading to excitotoxic motor neuron injury remain undefined.

Among CNS viral infections, alphaviruses and the related flaviviruses are important causes of fatal encephalomyelitis in humans worldwide. Most are transmitted in nature via infected mosquito vectors. While neurological disease caused by these viruses occurs with a wide array of clinical features, prominent spinal cord infection with paralysis and motor neuron destruction is one common phenotype (Solomon et al. 1998; Davis et al. 2006). Unfortunately, antiviral agents with activity against the alphaviruses and flaviviruses are not available, and consequently, management of patients with these infections remains supportive. In lieu of therapies directed against the pathogen itself, however, we have recently proposed that interventions can be targeted against detrimental host responses to exert neuroprotective effects (Nargi-Aizenman et al. 2004; Irani and Prow 2007; Prow and Irani 2007). If impaired glutamate transporter expression and/or function resulting from local tissue inflammation proves to occur in humans with these infections, then this cascade of events becomes even more important to understand and exploit as a novel treatment approach.

Beyond viral encephalomyelitis, glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity has now also been implicated in the pathogenesis of CNS inflammatory demyelinating diseases of both animals and humans (Pitt et al. 2000; Smith et al. 2000; Werner et al. 2001; Pitt et al. 2003; Srinivasan et al. 2005). In mice, blockade of AMPA receptors ameliorates clinical disease in the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) model without altering the amount of CNS inflammation or the extent of myelin loss (Pitt et al. 2000). Subsequent studies in EAE have shown that GLT-1 expression is profoundly reduced within demyelinated lesions, and that protein levels do not recover even after clinical remission (Ohgoh et al. 2002). Furthermore, this reduced expression is prevented in animals treated with NBQX, suggesting that AMPA receptor activation precedes the altered expression of glutamate transporters (Ohgoh et al. 2002). In humans with multiple sclerosis (MS), careful immunopathological study of cortical demyelination reveals that expression of EAAT1 and EAAT2 are selectively reduced in lesions where activated microglia are found (Vercellino et al. 2007). Soluble inflammatory mediators have been proposed to underlie these changes in transporter expression (Werner et al. 2001; Vercellino et al. 2007), but the specific molecular mechanisms are not known. Our data suggest that proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β could be responsible for these effects, and by extension, that inhibiting their production or action could offer a novel neuroprotective strategy for use in MS patients. Certainly, there are already approved compounds known to offer neuroprotection by increasing baseline astrocyte glutamate transporter expression (Rothstein et al. 2005).

Control of astroglial glutamate transporters can occur at a transcriptional, translational, or post-translational level. Specific transcription factors have been shown to directly repress the GLT-1/EAAT2 gene (Sitcheran et al. 2005; Li et al. 2006), and a common polymorphism in the EAAT2 promoter has recently been identified in humans that influences transcription factor binding and the susceptibility to excitotoxic injury following stroke (Mallolas et al. 2006). At post-transcriptional stages, some EAAT2 mRNAs contain lengthy 5’-untranslated regions that influence their translation (Tian et al. 2007). Even once a functional protein is expressed on the astrocyte cell surface, some cellular signals cause rapid transporter internalization (Kalandadze et al. 2002; González et al. 2005), while others inhibit transporter function without changing cell surface levels (Volterra et al. 1994; Trotti et al. 1996). Extracellular cytokines are known to inhibit GLT-1 transcription (Sitcheran et al. 2005), but we do not yet know to what degree our observed effects of IL-1β on GLT-1 function in vivo occur at a transcriptional level.

In conclusion, our data show that local production of IL-1β in the spinal cords of NSV-infected mice causes clinically-significant loss of the main astroglial glutamate transporter, GLT-1, and leads to excitotoxic damage of spinal motor neurons. Drugs that inhibit IL-1β production and/or action on IL-1 receptors protect against these cellular events and limit the development of paralysis. We believe these findings have important clinical implications for understanding the neurodegeneration that occurs with other CNS inflammatory diseases, as they offer a molecular pathway that is amenable to therapeutic manipulation.

Acknowledgements

These studies were supported by grants from the Robert Packard Center for ALS Research at Johns Hopkins (D.I.), the Charles A. Dana Foundation (D.I.), and by NIH grant AI057505 (D.I.).

Abbreviations used

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- AMPA

alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionate

- EAAT

excitatory amino acid transporter

- EAE

experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- GLT-1

glutamate transporter-1

- IL

interleukin

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- NBQX

1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-6-nitro-2,3-dioxobenzo(f)quinoxaline

- NSV

neuroadapted Sindbis virus

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

References

- Anderson CM, Swanson RA. Astrocyte glutamate transport: review of properties, regulation, and physiological functions. Glia. 2000;32:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barger SW, Goodwin ME, Porter MM, Beggs ML. Glutamate release from activated microglia requires the oxidative burst and lipid peroxidation. J. Neurochem. 2007;101:1205–1213. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04487.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boillée S, Yamanaka K, Lobsiger CS, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Kassiotis G, Kollias G, Cleveland DW. Onset and progression in inherited ALS determined by motor neurons and microglia. Science. 2006;312:1389–1392. doi: 10.1126/science.1123511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darman J, Backovic S, Dike S, Maragakis NJ, Krishnan C, Rothstein JD, Irani DN, Kerr DA. Viral-induced spinal motor neuron death is non-cell-autonomous and involves glutamate excitotoxicity. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:7566–7575. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2002-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis LE, DeBiasi R, Goade DE, Haaland KY, Harrington JA, Harnar JB, Pergam SA, King MK, DeMasters BK, Tyler KL. West Nile virus neuroinvasive disease. Ann. Neurol. 2006;60:286–300. doi: 10.1002/ana.20959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop J, Beal MH, She Y, Howland DS. Impaired spinal cord glutamate transport capacity and reduced sensitivity to riluzole in a transgenic superoxide dismutase mutant rat model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:1688–1696. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01688.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espey MG, Kustova Y, Sei Y, Basile AS. Extracellular glutamate levels are chronically elevated in the brains of LP-BM5-infected mice: a mechanism of retrovirus-induced encephalopathy. J. Neurochem. 1998;71:2079–2087. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71052079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González MI, Susarla BT, Robinson MB. Evidence that protein kinase C alpha interacts with and regulates the glial glutamate transporter GLT-1. J. Neurochem. 2005;94:1180–1188. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howland DS, Liu J, She Y, Goad B, Maragakis NJ, Kim B, Erickson J, Kulik J, DeVito L, Psaltis G, DeGennaro LJ, Cleveland DW, Rothstein JD. Focal loss of the glutamate transporter EAAT2 in a transgenic rat model of SOD1 mutant-mediated amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:1604–1609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032539299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irani DN, Prow NA. Neuroprotective interventions targeting detrimental host immune responses protect mice from fatal alphavirus encephalitis. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2007;66:533–544. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000263867.46070.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AC, Moench TR, Griffin DE, Johnson RT. The pathogenesis of spinal cord involvement in the encephalomyelitis of mice caused by neuroadapted Sindbis virus infection. Lab. Invest. 1987;56:418–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalandadze A, Wu Y, Robinson MB. Protein kinase C activation decreases cell surface expression of the GLT-1 subtype of glutamate transporter. Requirement of a carboxyl-terminal domain and partial dependence on serine 486. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:45741–45750. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203771200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn T, Magnus T, Jung S. Autoantigen specific T cells inhibit glutamate uptake in astrocytes by decreasing expression of astrocytic glutamate transporter GLAST: a mechanism mediated by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. FASEB J. 2005;19:1878–1880. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3748fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Mallory M, Alford M, Tanaka S, Masliah E. Glutamate transporter alterations in Alzheimer's disease are possibly associated with abnormal APP expression. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1997;56:901–911. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199708000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li LB, Toan SV, Zelenaia O, Watson DJ, Wolfe JH, Rothstein JD, Robinson MB. Regulation of astrocytic glutamate transporter expression by Akt: evidence for a selective transcriptional effect on the GLT-1/EAAT2 subtype. J. Neurochem. 2006;97:759–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang XH, Goldman JE, Jiang HH, Levine B. Resistance of interleukin-1beta-deficient mice to fatal Sindbis virus encephalitis. J. Virol. 1999;73:2563–2567. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2563-2567.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Hong JS. Neuroprotective effect of naloxone in inflammation-mediated dopaminergic neurodegeneration. Dissociation from the involvement of opioid receptors. Methods Mol. Med. 2003;79:43–54. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-358-5:43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallolas J, Hurtado O, Castellanos M, Blanco M, Sobrino T, Serena J, Vivancos J, Castillo J, Lizasoain I, Moro MA, Dávalos A. A polymorphism in the EAAT2 promoter is associated with higher glutamate concentrations and higher frequency of progressing stroke. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:711–717. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masliah E, Alford M, DeTeresa R, Mallory M, Hansen L. Deficient glutamate transport is associated with neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Ann. Neurol. 1996;40:759–766. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty MF. Down-regulation of microglial activation may represent a practical strategy for combating neurodegenerative disorders. Med. Hypotheses. 2006;67:251–269. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miralles VJ, Martinez-Lopez I, Zaragoza R, Borras E, Garcia C, Pallardo FV, Vina JR. Na+ dependent glutamate transporters (EAAT1, EAAT2, and EAAT3) in primary astrocyte cultures: effects of oxidative stress. Brain Res. 2001;922:21–29. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03124-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moisse K, Strong MJ. Innate immunity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1762:1083–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nargi-Aizenman JL, Griffin DE. Sindbis virus-induced neuronal death is both necrotic and apoptotic and is ameliorated by N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists. J. Virol. 2001;75:7114–7121. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.15.7114-7121.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nargi-Aizenman JL, Havert MB, Zhang M, Irani DN, Rothstein JD, Griffin DE. Glutamate receptor antagonists protect from virus-induced neural degeneration. Ann. Neurol. 2004;55:541–549. doi: 10.1002/ana.20033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda M, Nakanishi H, Akaike N. Glutamate release from microglia via glutamate transporter is enhanced by amyloid-beta peptide. Neuroscience. 1999;92:1465–1474. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohgoh M, Hanada T, Smith T, Hashimoto T, Ueno M, Yamanishi Y, Watanabe M, Nishizawa Y. Altered expression of glutamate transporters in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Neuroimmunol. 2002;125:170–178. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt D, Werner P, Raine CS. Glutamate excitotoxicity in a model of multiple sclerosis. Nat. Med. 2000;6:67–70. doi: 10.1038/71555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt D, Nagelmeier IE, Wilson HC, Raine CS. Glutamate uptake by oligodendrocytes: implications for excitotoxicity in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2003;61:1113–1120. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000090564.88719.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prow NA, Irani DN. The opioid receptor antagonist, naloxone, protects spinal motor neurons in a murine model of alphavirus encephalomyelitis. Exp. Neurol. 2007;205:461–470. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L, Block ML, Liu Y, Bienstock RJ, Pei Z, Zhang W, Wu X, Wilson B, Burka T, Hong JS. Microglial NADPH oxidase is a novel target for femtomolar neuroprotection against oxidative stress. FASEB J. 2005;19:550–557. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2857com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein JD, Martin LJ, Kuncl RW. Decreased glutamate transport by the brain and spinal cord in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1992;326:1464–1468. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199205283262204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein JD, Van Kammen MA, Levey I, Martin LJ, Kuncl RW. Selective loss of glial glutamate transporter GLT-1 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 1995;38:73–84. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein JD, Dykes-Hoberg M, Pardo CA, Bristol LA, Jin L, Kuncl RW, Kanai Y, Hediger MA, Wang Y, Schielke JP, Welty DF. Knockout of glutamate transporters reveals a major role for astroglial transport in excitotoxicity and clearance of glutamate. Neuron. 1996;16:675–686. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein JD, Patel S, Regan MR, Haenggeli C, Huang YH, Bergles DE, Jin L, Dykes-Hoberg M, Vidensky S, Chung DS, Toan SV, Bruijn LI, Su ZZ, Gupta P, Fisher PB. Beta-lactam antibiotics offer neuroprotection by increasing glutamate transporter expression. Nature. 2005;433:73–77. doi: 10.1038/nature03180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard AR, Rivest S. Neuroprotective effects of resident microglia following acute brain injury. J. Comp. Neurol. 2007;504:716–729. doi: 10.1002/cne.21469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitcheran R, Gupta P, Fisher PB, Baldwin AS. Positive and negative regulation of EAAT2 by NF-kappa B: a role for N-myc in TNF alpha-controlled repression. EMBO J. 2005;24:510–520. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T, Groom A, Zhu B, Turski L. Autoimmune encephalomyelitis ameliorated by AMPA antagonists. Nat. Med. 2000;6:62–66. doi: 10.1038/71548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon T, Kneen R, Dung NM, Khanh VC, Thuv TT, Ha DO, Dav NP, Nisalak A, Vaughn DW, White NJ. Poliomyelitis-like illness due to Japanese encephalitis virus. Lancet. 1998;351:1094–1097. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07509-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan R, Sailasuta N, Hurd R, Nelson S, Pelletier D. Evidence of elevated glutamate in multiple sclerosis using magnetic resonance spectroscopy at 3 T. Brain. 2005;128:1016–1025. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymocha R, Akaoka H, Dutuit M, Malcus C, Didier-Bazes M, Belin MF, Giraudon P. Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1-infected lymphocytes impair catabolism and uptake of glutamate by astrocytes via Tax-1 and tumor necrosis factor alpha. J. Virol. 2000;74:6433–6441. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.14.6433-6441.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi H, Jin S, Wang J, Zhang G, Kawanokuchi J, Kuno R, Sonobe Y, Mizuno T, Suzumura A. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces neurotoxicity via glutamate release from hemichannels of activated microglia in an autocrine manner. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:21362–21368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600504200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Watase K, Manabe T, Yamada K, Watanabe M, Takahashi K, Iwama H, Nishikawa T, Ichihara N, Kikuchi T, Okuyama S, Kawashima N, Hori S, Takimoto M, Wada K. Epilepsy and exacerbarion of brain injury in mice lacking the glial glutamate transporter GLT-1. Science. 1997;276:1699–1702. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5319.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thach DC, Kimura T, Griffin DE. Differences between C57BL/6 and BALB/cBy mice in mortality and virus replication after intranasal infection with neuroadapted Sindbis virus. J. Virol. 2000;74:6156–6161. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.13.6156-6161.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian G, Lai L, Guo H, Lin Y, Butchbach ME, Chang Y, Lin CL. Translational control of glial glutamate transporter EAAT2 expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:1727–1737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609822200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilleux S, Hermans E. Neuroinflammation and regulation of glial glutamate uptake in neurological disorders. J. Neurosci. Res. 2007;85:2059–2070. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotti D, Rossi D, Gjesdal O, Levy LM, Racagni G, Danbolt NC, Volterra A. Peroxynitrite inhibits glutamate transporter subtypes. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:5976–5979. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.5976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vercellino M, Merola A, Piacentino C, Votta B, Capello E, Mancardi GL, Mutani R, Giordana MT, Cavalla P. Altered glutamate reuptake in relapsing-remitting and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis cortex: correlation with microglia infiltration, demyelination, and neuronal and synaptic damage. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2007;66:732–739. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e31812571b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volterra A, Trotti D, Tromba C, Floridi S, Racagni G. Glutamate uptake inhibition by oxygen free radicals in rat cortical astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 1994;14:2924–2932. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-02924.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Pekarskava O, Bencheikh M, Chao W, Gelbard HA, Ghorpade A, Rothstein JD, Volsky DJ. Reduced expression of glutamate transporter EAAT2 and impaired glutamate transport in human primary astrocytes exposed to HIV-1 or gp120. Virology. 2003;20:60–73. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Trillo-Pazos G, Kim SY, Canki M, Morgello S, Sharer LR, Gelbard HA, Su ZZ, Kang DC, Brooks AI, Fisher PB, Volsky DJ. Effects of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 on astrocyte gene expression: potential role in neuropathogenesis. J. Neurovirol. 2004;10(Suppl):25–32. doi: 10.1080/753312749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warita H, Manabe Y, Murakami T, Shiote M, Shiro Y, Hayashi T, Nagano I, Shoji M, Abe K. Tardive decrease of astrocytic glutamate transporter protein in transgenic mice with ALS-linked mutant SOD1. Neurol. Res. 2002;24:577–581. doi: 10.1179/016164102101200384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner P, Pitt D, Raine CS. Multiple sclerosis: altered glutamate homeostasis in lesions correlates with oligodendrocyte and axonal damage. Ann. Neurol. 2001;50:169–180. doi: 10.1002/ana.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss-Coray T. Inflammation in Alzheimer disease: driving force, bystander or beneficial response? Nat. Med. 2006;12:1005–1015. doi: 10.1038/nm1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye ZC, Sontheimer H. Cytokine modulation of glial glutamate uptake: a possible involvement of nitric oxide. Neuroreport. 1996;7:2181–2185. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199609020-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong VW, Wells J, Giuliani F, Casha S, Power C, Metz LM. The promise of minocycline in neurology. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:744–751. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00937-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S, Stavrovskaya IG, Drozda M, Kim BY, Ona V, Li M, Sarang S, Liu AS, Hartley DM, Wu DC, Gullans S, Ferrante RJ, Przedborski S, Kristal BS, Friedlander RM. Minocycline inhibits cytochrome c release and delays progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mice. Nature. 2002;417:74–78. doi: 10.1038/417074a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]