Abstract

Amide Proton Transfer (APT) imaging is a type of chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), in which amide protons of endogenous mobile proteins and peptides in tissue are detected. Initial studies have shown promise to distinguish tumor from surrounding brain in patients, but this data was hampered by magnetic field inhomogeneity and by low signal to noise ratio (SNR). Here a practical six-offset APT data acquisition scheme is presented that, together with a separately acquired CEST spectrum, can provide B0-inhomogeneity corrected human brain APT images of sufficient SNR within a clinically relevant time frame. Data from nine brain tumor patients at 3T shows that APT intensities were significantly higher in the tumor core, as assigned by gadolinium-enhancement, than in contralateral normal appearing white matter (CNAWM) in patients with high-grade tumors. Conversely, APT intensities in tumor were indistinguishable from CNAWM in patients with low-grade tumors. In high-grade tumors, regions of increased APT extended outside of the core into peripheral zones, indicating the potential of this technique for more accurate delineation of the heterogeneous areas of brain cancers.

Keywords: CEST, APT, magnetization transfer, brain tumor, field inhomogeneity, MRI

Introduction

Recent progress in the field of proteomics (1–3) has shown that the biological characteristics of human gliomas and other cancers are defined by numerous proteins and that the pathologic distinctions between normal and malignant tissues can be identified at the level of protein expression. Using in vivo proton MRS, Howe et al. (4) showed that the MRS-detectable mobile macromolecular proton concentration is higher in human brain tumors than in normal white matter, and increases with tumor grade. These advances have prompted much interest in visualizing the protein content of tumors in vivo in MRI.

Chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST) has recently emerged as a new contrast mechanism for MRI (5–7) in the field of cellular and molecular imaging. This technique, which is a type of magnetization transfer (MT) imaging (8), has now evolved into several different variants as new CEST contrast agents (diamagnetic and paramagnetic) and approaches have been designed (9–22). In one of these, dubbed amide proton transfer (APT) imaging (9–13,23–25), endogenous cytosolic proteins and peptides are detected through saturation of the amide protons in the peptide bonds. Similar to the results by Howe et al. (4), this unique amide proton-based MRI contrast mechanism has shown promise for imaging the increase in protein and peptide content in brain tumors in animals (11), as well as in an initial study in human brain tumor patients (23). However, these preliminary human studies were confounded by low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) (the APT effect is only a few percent of the water signal) and by local field inhomogeneity. The high sensitivity of APT to field inhomogeneity is due to the inherent approach in CEST-type imaging, where water saturation is measured as a function of transmitter frequency, producing the “z-spectra” (26) or CEST spectra (5). Such spectra are dominated by large direct water saturation around the water frequency at about 4.7 ppm in the proton spectrum and other saturation effects such as conventional MT based on semi-solid tissue structures (8). The effects of the saturation transfer of exchangeable protons to water are subsequently identified by asymmetry analysis with respect to this water signal (27), which, for convenience, is assigned to a reference frequency of 0 ppm. In MRI, shimming and radiofrequency (RF) offset settings are based on the NMR signal from a whole volume or tissue (e.g., a head) and individual voxels generally have a somewhat different water frequency offset. Such a small shift in the center of the z-spectrum can easily cause a few percent change in the asymmetry data, making the asymmetry analysis procedure inherently sensitive to field inhomogeneity, often resulting in large artifacts (23).

It has been shown that the B0 inhomogeneity in CEST imaging can be corrected on a voxel-by-voxel basis through the centering of the z-spectrum (10,11,23), but this would require acquisition of saturation images at 20–40 frequencies. As SNR of APT images is low, multiple acquisitions for each frequency offset of complete z-spectra would be needed, which is not practical in patients. The initial human studies used a two-offset approach symmetric around the global water frequency center (23), causing significant field-inhomogeneity-based image artifacts in many regions, especially in the frontal lobe and near the skull. In this study, we demonstrate that a practical six-offset multi-acquisition method (Fig. 1) combined with a single reference z-spectrum to acquire high-SNR APT images can accomplish improved APT imaging with B0 inhomogeneity correction within an acceptable scanning time (about 4.5 min), and assess whether this improvement can enhance MRI characterization of human brain tumors.

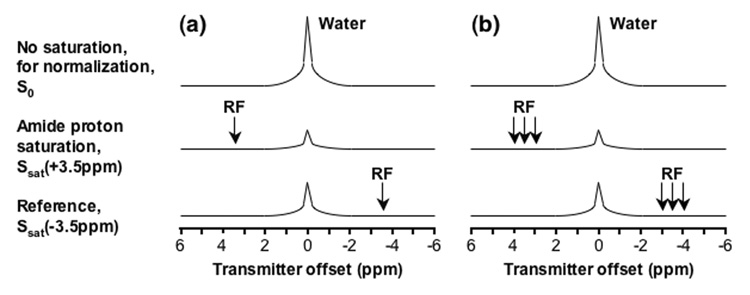

Fig. 1. Schemes for APTw image acquisition.

(a) Standard two-offset APT scan (+3.5 ppm for label, −3.5 ppm for reference). (b) Six-offset APT scan (±3, ±3.5, ±4 ppm) used in this study. The effects of conventional MT and direct water saturation reduce the water signal intensities at all offsets (±3, ±3.5, ±4 ppm), and the existence of APT causes an extra reduction around the offset of 3.5 ppm.

Materials and Methods

Patient Recruitment

Nine patients with histologically-confirmed gliomas of varying grade (Table 1) were investigated: three patients with glioblastoma multiforme (GBM, World Health Organization (WHO) grade IV), one with anaplastic astrocytoma (AA, WHO grade III), two with anaplastic oligodendroglioma (AO, WHO grade III), and three with low-grade brain tumor (astrocytoma (LGA) or oligodendroglioma (LGO), WHO grade II). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to involvement in this Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant study.

Table 1.

APT MRI results for human brain tumor patients

| Patient no. | Sex | Lesion location | Diagnosis | Gd enhancement | APTw intensity (%) a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor core b | Tumor periphery c | CNAWM | |||||

| 1 | F | Left temporal | GBM | Yes | 3.8±1.0 | 2.9±1.0 | 1.5±0.4 |

| 2 | M | Right frontal | GBM | Yes | 2.8±1.2 | 2.5±0.5 | 1.3±0.8 |

| 3 | M | Left parietooccipital | GBM | Yes | 3.2±0.6 | 2.7±0.3 | 1.9±0.4 |

| 4 | M | Left frontal | AO | Yes | 2.8±0.4 | 2.5±0.5 | 1.6±0.4 |

| 5 | M | Left frontal | AO | Yes | 2.0±0.5 | 1.2±0.9 | 1.9±0.7 |

| 6 | F | Left parietooccipital | AA | Yes | 2.7±0.3 | 2.6±0.3 | 1.7±0.2 |

| Average | 2.9±0.6 | 2.4±0.6 | 1.7±0.2 | ||||

| 7 | F | Left frontoparietal | LGO | No | 1.4±0.2 d | 1.2±0.3 | |

| 8 | F | Left frontal | LGO | No | 1.1±0.7 d | 1.4±0.7 | |

| 9 | M | Right parietal | LGA | No | 1.0±0.3 d | 1.0±0.4 | |

| Average | 1.2± 0.2 d | 1.2±0.2 | |||||

Mean ± standard deviation

As identified by Gd-T1w imaging (Gd-enhancing area).

Difference between areas with FLAIR abnormality and Gd-enhancement.

For areas of FLAIR abnormality.

MRI Acquisition

Experiments were performed on a Philips 3T MRI scanner (Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands) using a body coil for RF transmission and a 6-channel phased-array coil for reception. A continuous-wave (CW) RF saturation scheme was used of power 4 µT and duration 500 ms (which currently is the longest allowed for our body coil). A single-slice turbo spin-echo (TSE) imaging readout with a SENSE (sensitivity encoding) factor of 2 and a TSE factor (number of refocusing pulses) of 32 was used (which therefore equals a single-shot acquisition of 64 phase-encoding steps). Other imaging parameters were: TR/TE = 3000/30ms, matrix = 128×64 (zero-filled to 256×256), FOV = 200×200 mm2, and slice thickness = 5 mm. Higher-order (up to second order) shimming was employed in this study. High-SNR APT-weighted (APTw) images were acquired using six frequency offsets (namely, ±3, ±3.5, ±4 ppm) and 8 signal averages. In an extra scan, a z-spectrum was acquired (33 offsets from 8 to −8 ppm with intervals of 0.5 ppm, one average). For both scans, one unsaturated image (without RF saturation, same TR) was acquired for normalization. The scan times were 2 min 48 sec and 1 min 42 sec, respectively, totaling 4 min 30 sec for these two scans. In addition, higher-order shimming was incorporated into the prescan of the high-SNR APT scan and performed by the scanner automatically, which took about 10 sec extra. Because four extra offsets around ±3.5 ppm were acquired in the high SNR scan, it is possible to correct for the artifacts caused by B0 inhomogeneity (see below).

Standard T2-weighted (T2w), T1-weighted (T1w), fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), and gadolinium-enhanced T1w (Gd-T1w) images were acquired for reference. The parameters used were: T2w (TSE factor = 8, TR/TE = 4000/80 ms, 60 slices, 2.2 mm thick), T1w and Gd-T1w (three-dimensional (3D) magnetization-prepared-rapid-gradient-echo (MPRAGE), TR/TE/TI = 3000/3.7/843 ms, flip angle = 8°, 120 slices, 1.1 mm isotropic voxels), and FLAIR (TSE factor = 19, TR/TE/TI = 11000/120/2800 ms, 60 slices, 2.2 mm thick). Conventional MT imaging was incorporated into the high-SNR APT scan (with the same parameters, except offset = 2000 Hz) and acquired simultaneously to share its non-saturated (S0) image.

Theoretical Considerations

The definitions and nomenclature used here are equivalent to previous papers (10,11,23,24). Briefly, the MT ratio (MTR) is defined as: MTR = 1 – Ssat/S0, in which Ssat and S0 are the signal intensities with and without selective irradiation, respectively. APT contrast is based on a change in bulk water intensity due to chemical exchange with saturated amide protons of endogenous mobile proteins and peptides. To reduce interference of other saturation and/or spectral broadening effects that occur concurrently with APT, such as direct water saturation, conventional MT (8), and even blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) (28) effects, it is useful to define an MTR asymmetry (MTRasym) parameter (7,27) with respect to the water frequency:

| [1] |

As demonstrated previously (10,11,23), the resulting MTRasym curve depends not only on the proton transfer ratio (PTR) of the contributing exchangeable protons but also on other non- CEST components (). Under zero-order approximation, we have:

| [2] |

As shown previously (10,11,23), has a complicated origin, such as the inherent MTRasym of the solid-phase MT effect (29) and possible intramolecular and intermolecular nuclear Overhauser effects (NOE) of aliphatic protons of mobile macromolecules and metabolites (10,30,31), and it may cause a negative background for asymmetry analysis of z-spectra. When B0 field homogeneity is poor, the water resonance signals for some voxels may not be centered properly at the offset of 0 ppm. In such voxels, may also include the contributions due to B0 field inhomogeneity. For the amide protons of mobile protein and peptides, we abbreviate the amide PTR at 3.5 ppm as APTR. Namely,

| [3] |

To account for the presence of , the MTRasym(3.5ppm) images calculated by Eq. [3] are called APTw images.

Data Analysis

All data processing procedures were performed using Interactive Data Language (IDL, Research Systems, Inc., Boulder, CO, USA). The full CEST spectrum with 33 offsets was fitted through all offsets using a 12th-order polynomial (the maximum order available with IDL) on a voxel-by-voxel basis. After this, the fitted curve was calculated using an offset resolution of 1 Hz (namely, 2049 points). The actual water resonance was assumed to be at the frequency with the lowest signal intensity. The deviation from the water frequency in Hz was used to form a map of water center frequency offsets. To determine the field inhomogeneity effects on z-spectra, the measured z-spectrum for each voxel was interpolated to 2049 points and shifted along the direction of the offset axis to correspond to 0 ppm at its lowest intensity. The realigned z-spectra were interpolated back to 33 points for visual purposes, and the outermost points of ±7.5 and ±8 ppm were excluded in the display. Further, to correct for the field inhomogeneity effects on high-SNR APT images, the acquired APT data for offsets (+4, +3.5, +3 ppm or +512, +448, +384 Hz at 3T) for each voxel were interpolated to 257 points over the range from +4.5 to +2.5 ppm (namely +576, +575, …, +320 Hz) and shifted using the fitted z-spectrum central frequency offset for the same voxel. A similar procedure was applied to the negative-offset data (−3, −3.5, −4 ppm). Finally, the corrected high-SNR APT images were calculated using the two offsets ±3.5 ppm in the shift-corrected data. The asymmetry image was thresholded based on the signal intensity of S0 images to remove voxels outside the brain. This was necessary because signal intensities outside the brain were close to the noise level in S0 and created artificially large values in the asymmetry image.

For each of the multi-slice or 3D images, a single slice matching with the APT scans was chosen for quantitative analysis. For Gd-enhancing brain tumors, three regions of interest (ROIs; tumor core, tumor periphery, and contralateral normal-appearing white matter or CNAWM) were drawn according to the FLAIR and Gd-T1w images. We assigned areas with FLAIR abnormality as tumor, in which Gd-enhanced regions were further assigned as tumor cores, and the rest as tumor periphery. For tumors without gadolinium enhancement, only two ROIs (tumor and CNAWM) could be used.

Results

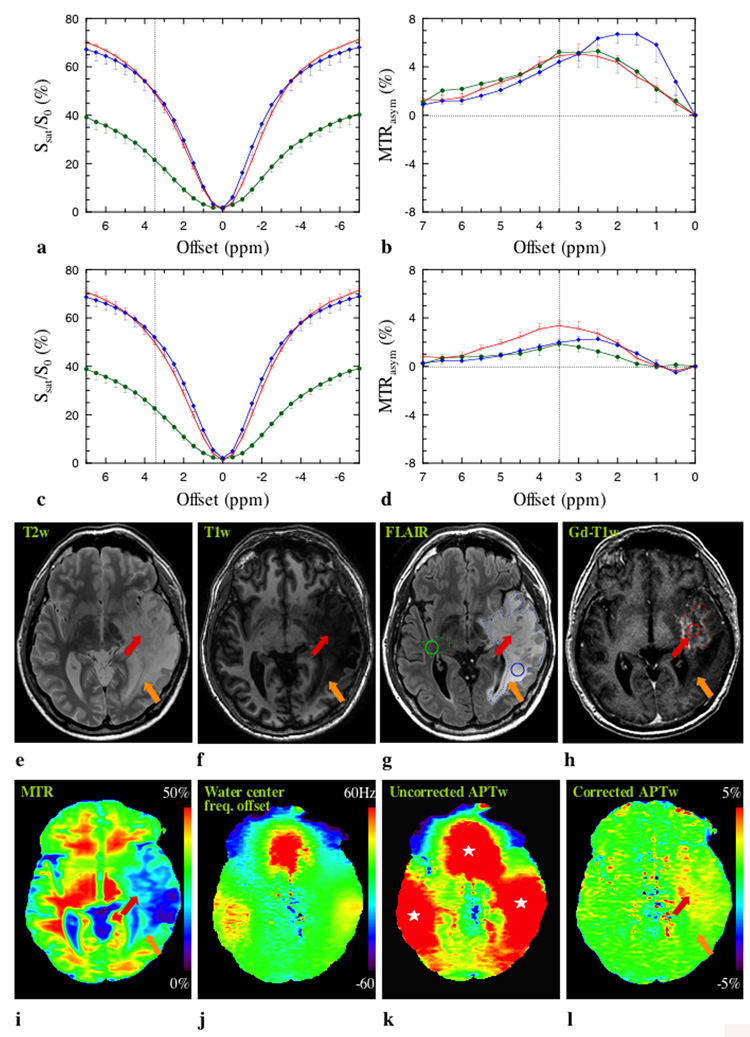

Figure 2 shows data for patient 4 who had a pathologically-proven WHO grade III oligodendroglioma. The effects of conventional MT and direct water saturation dominate the z-spectra (Fig. 2a and c). The upward shift in the z-spectra for tumor core and periphery may be attributed to many factors (32), such as increased water content and increased macromolecular mobility in these regions. It can be seen that the z-spectra corrected on a voxel-by-voxel basis are more symmetrical around the water resonance. Although tumor core and periphery are not distinguishable at the offset of 3.5 ppm in the z-spectra, a small APT effect is visible in the offset range of 2–4 ppm downfield from the water resonance in the MTRasym spectra (Fig. 2b and d). When corrected for B0 inhomogeneity, the tumor core MTRasym curve is maximized at 3.5 ppm (dotted vertical line) and occupies a larger area than edema and CNAWM, presumably due to higher protein and peptide concentration in gliomas (1–4).

Fig. 2. MR images of a patient with WHO grade III oligodendroglioma.

a: Uncorrected z-spectra for tumor core (red), tumor periphery (blue), and CNAWM (dark green). b: Corresponding MTRasym spectra. c and d: B0-inhomogeneity corrected data (corresponding to a and b). After correction, the resulting MTRasym curve for the tumor is maximized at 3.5 ppm, where the amide protons of mobile proteins and peptides resonate. e: T2w image. f: T1w image. g: FLAIR image. h: Gd-T1w image. i: MTR map. j: Water center-frequency offset map. k: Uncorrected APTw image. l: Corrected APTw image. The water center-frequency map (j) as derived from z-spectrum shows field inhomogeneity near air-tissue interfaces (sinus, ear), leading to large artifacts (white stars) in the uncorrected APTw image (k), which disappear in the frequency-corrected APTw image (l). Elevated APT signal can be seen in Gd-enhanced tumor core (red arrow). In the tumor periphery (FLAIR abnormality minus Gd-enhanced portion), both areas of APT hyperintensity and normal APT intensity (orange arrow) can be seen. The ROIs used for z-spectrum analysis (a-d, about 20 pixels each ROI) and for APTw quantitative analysis (Table 1) are shown in the FLAIR (g) and Gd-T1w (h) images.

The T2w, T1w, and FLAIR images (Fig. 2e–g) show a large lesion, in which the difference between tumor core (as identified by Gd-T1w (Fig. 2h)) and peripheral zone is not well demarcated. In addition, both tumor core and periphery show low MTR values (Fig. 2i). Even though a variation in intensity between these two areas is visible, the area with the lowest MTR does not completely overlap with the tumor core. When comparing Fig. 2k with Fig. 2j, it can be seen that the three large red areas (marked by white stars) in the uncorrected APTw image are the result of susceptibility artifacts near air-tissue interfaces (sinus, ear) (23). Fortunately, these artifacts could be corrected by the six-offset approach (Fig. 2l), which generated images that are homogenous on most of the slice, except in a large area within the tumor. In tumor core (red arrow) an increase in APT signal intensity compared to normal appearing white matter on the APTw images can be clearly seen. This hyperintense area is much smaller than the abnormal area on T2w, T1w, FLAIR, and MTR and appears associated with the most solid aspects of the lesion (Gd-enhancing portion) and some areas nearby. Areas of lower APT signal, on the other hand, are most consistent with tumor periphery (orange arrow).

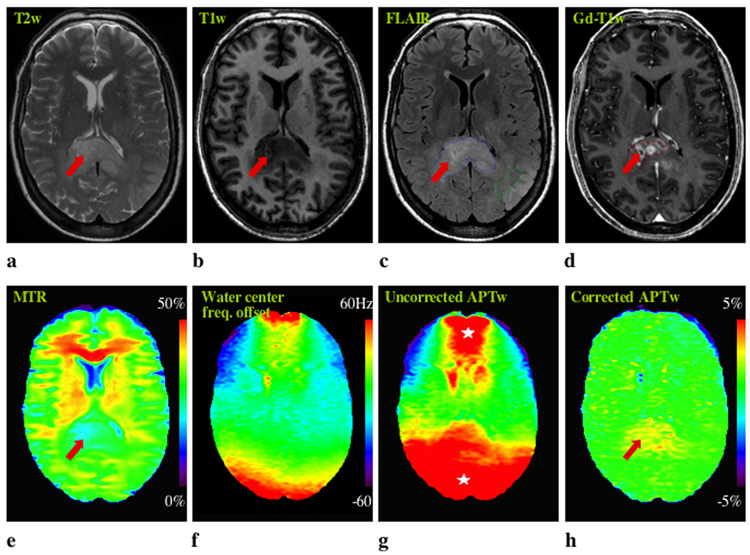

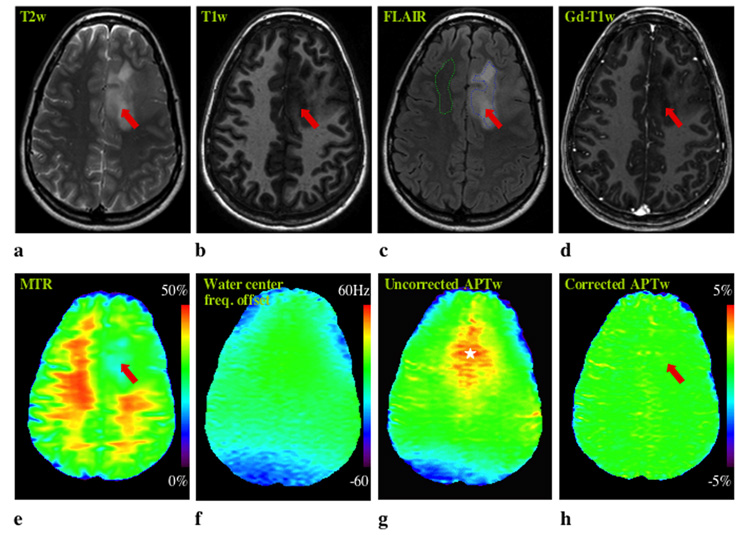

Figure 3 shows MR imaging for patient 6 who had anaplastic astrocytoma. In the uncorrected APT image, two large red spots are visible in the frontal and occipital lobes, which may be erroneously attributed to tumor tissue. However, these are B0 inhomogeneity-induced artifacts, which disappear in the corrected APT image. In this patient, the abnormality on the APTw image is comparable in size to that on the T2w, T1w, FLAIR, and MTR images, but larger than that on the Gd-T1w image. Figure 4 shows MRI data for a pathologically-confirmed low-grade oligodendroglioma (Patient 7). Again, a clear B0 inhomogeneity-induced artifact is visible in the uncorrected two-offset APTw image. Interestingly, T2w, T1w, FLAIR, and MTR images all highlight the tumor, while no obvious lesion or signal enhancement can be found in this region on either the APTw or Gd-T1w images. Again, APT imaging shows a tumor appearance unique from conventional MRI, including MTR.

Fig. 3. MR images of a patient with an anaplastic astrocytoma.

a: T2w. b: T1w. c: FLAIR. d: Gd-T1w. e: MTR. f: z-spectrum center frequency map. g: Uncorrected APTw. g: Center-frequency-corrected APTw. The ROIs for quantitative analysis (Table 1) are shown in the FLAIR (c) and Gd-T1w (d) images. B0 field inhomogeneity (f) causes some large artifacts (white stars) in the uncorrected APTw image (g). The hyperintense APTw area (h) is comparable in size to the lesion identified on T2w (a), T1w (b), FLAIR (c), and MTR (e), but larger than that on the Gd-T1w image.

Fig. 4. MR images of a patient with a low-grade oligodendroglioma.

a: T2w. b: T1w. c: FLAIR. d: Gd-T1w. e: MTR. f: z-spectrum center frequency map. g: Uncorrected APTw. g: Corrected APTw. The B0 field inhomogeneity is obvious (f), causing a large susceptibility artifact (white star) near the ethmoid sinus area in the uncorrected APTw image (g). Despite clear abnormalities (red arrow) on T2w (a), T1w (b), FLAIR (c), and MTR (e), there is no visible signal enhancement in tumor on both the Gd-T1w (d) and APTw (h) images. The ROIs for quantitative analysis (Table 1) are shown in the FLAIR image (c).

A quantitative analysis of the corrected APT images from all nine patients is shown in Table 1. For high-grade patients (n = 6), APT image intensity is significantly higher in tumor core (identified by Gd-T1w) than in tumor periphery (P = 0.01, two-tailed paired Student’s t-test) and CNAWM (P = 0.008). For low-grade patients (n = 3), the APT signal intensity in tumor could not be distinguished from CNAWM (P = 0.8). In addition, the signal enhancement on APTw images significantly increases with tumor grade (P = 0.004 with two-tailed unequal Student’s t-test).

Discussion

Technical Issues

When using an asymmetry procedure to analyze saturation spectra, small shifts in frequency will have large effects on the results. Consequently, B0 inhomogeneity poses a significant problem for APT imaging especially for large organs, such as the human brain. The results in this pilot study show that correction of APT data for local frequency shifts is necessary to obtain correct data. Although higher-order slice shimming was used in our study and B0 inhomogeneity was acceptable (typically less than 20 Hz over most of the slice, Fig. 2j, Fig 3f, and Fig 4f), large artifacts were apparent in the sinus and ear areas, where center frequency shifts were as large as 60–80 Hz (0.47–0.63 ppm). However, even very small shifts (a few Hz) can have detrimental effects because the slope of the z-spectrum is very steep (Fig. 2a and c) due to the direct water saturation around 0 ppm. Unfortunately, the APT effect is small (low SNR) and the acquisition of complete z-spectra is slow, making the approach difficult for clinical use. Our previous study used a two-offset (±3.5 ppm) acquisition scheme with multiple scans to increase SNR. However, B0 inhomogeneity correction is not possible for such two-offset APT data, unless a theoretical model can be established (33), which is difficult in vivo. As a compromise between optimum SNR and the ability for some correction, we designed a scheme in which eight image averages are taken at six offsets around the approximate amide resonance frequency (three on the positive offset side and three on the negative offset side) and an extra z-spectrum is acquired to determine local frequency shifts. It is important to point out that the extra z-spectrum scan should be performed with the same experimental conditions as the high-SNR APT scan, i.e., no prescan should be applied, as this may change shim and frequency offset settings.

When using the six-offset APT imaging acquisition method presented here, it is important to select a proper offset interval that can cover the corresponding B0 field inhomogeneity, which depends on the type and size of tissue studied and on the magnetic field strength. If inhomogeneity is worse, as determined by the z-spectrum experiment, a larger offset interval for the three points will be required. For example, when the B0 inhomogeneity is as large as 140–160 Hz (about 1.1–1.3 ppm) for some voxels at 3T, the offsets (±2.75, ±3.5, ±4.25 ppm) may be used. However, the offset interval cannot be too large, because the interpolation error may be too big. In this case, it may be necessary to use some extra frequency offsets to reduce the interval size, for example, by extending the six-offset method to a ten-offset acquisition scheme.

An important consideration for the quality of the APT experiment is that SNR should be sufficiently high to measure the small effects. Obviously, the number of scans will depend on the experimental conditions, especially field strength and coils used. For saturation experiments, the main restrictions are specific absorption rate (SAR) and scanner pulse length limitations. Our previous study (23) was performed using a transmit/receive (T/R) head coil, allowing the use of long saturation pulses (3 s at 3 µT). Modern MRI scanners often use body coil excitation with phased-array coil receive to allow parallel image acquisition. However, power deposition increases with the square of the coil radius, and the saturation pulse is currently limited to 500 ms on our scanner. The APTR as a function of saturation time, tsat, is given by (34):

| [4] |

in which APTR∞ is the APTR value when tsat → ∞, i.e., allowing maximum transfer, and R1w is the spin-lattice relaxation rate of water. It can thus be estimated that the sensitivity of APT for the phased-array coil setup is reduced by approximately 60–70% due to the short RF label/transfer time. However, the experimental results as presented in this study show that overall sensitivity is increased when using the phased-array coil and sufficient SNR can be attained.

As a point of interest, the observant reader may notice that the MTRasym plot for the phased-array coil setup is consistently positive in the offset range up to 8 ppm (Figs. 2b and d). However, the MTRasym curve for the T/R coil setup in this range was initially positive and then negative, due to the longer RF saturation time used and the concomitant changes in the shape of the direct saturation part of the z-spectrum. One issue with APT studies therefore is that the results depend on experimental conditions, which complicates comparisons between laboratories. In the future a standard will have to be designed for the method to become clinically relevant.

Clinical Potential of APT Imaging

Gliomas are highly infiltrative and almost universally fatal. These tumors consist of cores of solid tumor (often mixed with necrosis), surrounded by regions of edematous brain often infiltrated by tumor cells. Although MRI is the standard of care for assessing these tumors before, during, and after therapy (35), it still has limited diagnostic specificity with regard to the ability to distinguish tumor grade or to separate the mass of solid tumor from the surrounding edema. For instance, T2w or FLAIR hyperintensities on MRI may be due to either solid tumor mass or peritumoral edema. Like T2w images, diffusion-weighted images (DWI) usually show poor contrast between tumor and edema (36). However, apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) and diffusion anisotropy are currently being investigated as approaches to distinguish tumor type and to separate solid tumor from tumor-related edema (37–39). This is a promising approach, but may not be straightforward as the ADC of tumor and edema may depend on the water content and perfusion characteristics of the particular tumor. When using Gd-enhanced imaging, only the tumor area where the blood-brain barrier is disrupted is visible, although the actual tumor is known to extend further (40). Currently, surgical resection targets the bulk of the T1w contrast-enhancing tumor with or without a portion of the surrounding tissue with abnormal T2w or FLAIR signal. Attempts are made to limit the resection of brain tissue affected primarily by edema as these areas may recover normal function after resection. However, there is no unified approach to maximize the resection of tumor-laden tissue. In addition, Gd approaches are limited in that approximately 10% of glioblastomas and 20–30% of anaplastic astrocytomas show no enhancement (41). There are also concerns about the long-term safety of Gd exposure. Hence, there is an urgent need for new imaging approaches to distinguish the maximal volume of tissue in order to assist resection and the likely histology that may alter treatment recommendations.

APT imaging is able to provide imaging features of brain tumors that are distinct from those produced by conventional MR sequences. Animal research using higher-resolution imaging (11) has shown that the tumor core and edema can be separated. Even though clinical scans are limited by time and spatial resolution, the initial data presented here and in our previous report (23) demonstrate the potential of this approach. The data in Table 1 indicate that for contrast-enhancing tumors the highest APT intensity is associated with the most solid aspects of the lesion (Gd-enhancing portion), while negligible APT hyperintensity appears in low-grade tumors. Even though the sample size is limited (n = 9), a clear correlation with grade could be established (r-squared = 0.92). More interestingly, the hyperintense regions on APTw images are generally larger than the areas of contrast enhancement on Gd-T1w images, but smaller than the abnormal areas designated as tumor on T2w, T1w, FLAIR, or even MTR. APT images therefore provide unique imaging characterization of tumors, potentially delineating the tumor core from peritumoral edema more accurately than Gd-based imaging alone. Such data, when validated with targeted biopsies to correlate histopathology with APT intensities, could be extremely helpful in planning maximal tumor resections. This is particularly notable as about 80% of recurrent brain tumors occur at the resection margin. It is possible that more extensive resection to include areas of APT hyperintensity (when feasible) may reduce tumor recurrence.

Finally, it is important to mention that increased APTR in the tumor can potentially be caused by increased cytosolic protein and peptide content and increased intracellular pH in the tumor (10,11,23), as compared to the normal brain tissue. Thus, care has to be taken in interpreting the results. Although extra validation experiments are required, the increased protein and peptide content in the tumor is the most likely explanation due to the fact that only a small intracellular pH increase (< 0.1 unit) is often detected in the tumor (42,43). The results in this study are consistent with increasing mobile protein concentrations in malignant tumors measured previously by Howe et al. (4) using single-voxel MRS. Note that, as shown in our water exchange experiments (30), the aliphatic signals studied by Howe et al. (4) are related to the amide proton resonance downfield from the water signal through intramolecular dipolar interaction (i.e., NOE) with these proton groups. Such amide proton signals have also been shown to be increased in perfused tumor cells (30). Therefore, APT imaging may provide visual information about the presence and grade of tumor based on increased content of mobile proteins and peptides.

Conclusions

We demonstrated a practical six-offset APT-MRI method that, in combination with a full CEST reference spectrum, was able to correct for the artifacts caused by B0 inhomogeneity on human brain APT images. APT imaging does not require contrast injection and the initial results suggest that APT, based on endogenous contrast generated through irradiation of amide groups in the peptide bonds of proteins and peptides, is correlated to tumor grade and provides unique imaging features in gliomas by distinguishing tumor zones. These unique features of APT imaging, not available in other routine MR approaches, may prove valuable for maximizing diagnostic accuracy and guiding surgical resection of human brain tumors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Craig Jones, Ms. Terri Brawner, Ms. Kathleen Kahl, and Ms. Ivana Kusevic for experimental assistance. Dr. van Zijl is a paid lecturer for Philips Medical Systems. This arrangement has been approved by Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. This work was supported in part by grants from NIH (RR015241, EB002634, and EB002666), Whitaker Foundation, and Dana Foundation.

References

- 1.Hobbs SK, Shi G, Homer R, Harsh G, Altlas SW, Bednarski MD. Magnetic resonance imaging-guided proteomics of human glioblastoma multiforme. J Magn Reson Imag. 2003;18:530–536. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li J, Zhuang Z, Okamoto H, Vortmeyer AO, Park DM, Furata M, Lee Y-S, Oldfield EH, Zeng W, Weil RJ. Proteomic profiling distinguishes astrocytomas and identifies differential tumor markers. Neurology. 2006;66:733–736. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000201270.90502.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen J, Behrens B, Wistuba II, Feng L, Lee JJ, Hong WK, Lotan R. Identification and validation of differences in protein levels in normal, premalignant, and malignant lung cells and tissues using high-throughput Western array and immunohischemistry. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11194–11206. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howe FA, Barton SJ, Cudlip SA, Stubbs M, Saunders DE, Murphy M, Wilkins P, Opstad KS, Doyle VL, McLean MA, Bell BA, Griffiths JR. Metabolic profiles of human brain tumors using quantitative in vivo 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:223–232. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ward KM, Aletras AH, Balaban RS. A new class of contrast agents for MRI based on proton chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST) J Magn Reson. 2000;143:79–87. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang S, Merritt M, Woessner DE, Lenkinski R, Sherry AD. PARACEST agents: modulating MRI contrast via water proton exchange. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:783–790. doi: 10.1021/ar020228m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou J, van Zijl PC. Chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging and spectroscopy. Progr NMR Spectr. 2006;48:109–136. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolff SD, Balaban RS. Magnetization transfer contrast (MTC) and tissue water proton relaxation in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 1989;10:135–144. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910100113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goffeney N, Bulte JWM, Duyn J, Bryant LH, van Zijl PCM. Sensitive NMR detection of cationic-polymer-based gene delivery systems using saturation transfer via proton exchange. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:8628–8629. doi: 10.1021/ja0158455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou J, Payen J, Wilson DA, Traystman RJ, van Zijl PCM. Using the amide proton signals of intracellular proteins and peptides to detect pH effects in MRI. Nature Med. 2003;9:1085–1090. doi: 10.1038/nm907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou J, Lal B, Wilson DA, Laterra J, van Zijl PCM. Amide proton transfer (APT) contrast for imaging of brain tumors. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:1120–1126. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McMahon MT, Gilad AA, Zhou J, Sun PZ, Bulte JWM, van Zijl PCM. Quantifying exchange rates in chemical exchange saturation transfer agents using the saturation time and saturation power dependencies of the magnetization transfer effect on the magnetic resonance imaging signal (QUEST and QUESP): pH calibration for poly-L-lysine and a starburst dendrimer. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:836–847. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilad AA, McMahon MT, Walczak P, Winnard PT, Raman V, van Laarhoven HWM, Skoglund CM, Bulte JWM, van Zijl PCM. Artificial reporter gene providing MRI contrast based on proton exchange. Nature Biot. 2007;25:217–219. doi: 10.1038/nbt1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Zijl PCM, Jones CK, Ren J, Malloy CR, Sherry AD. MRI detection of glycogen in vivo by using chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging (glycoCEST) Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 2007;104:4359–4364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700281104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang S, Winter P, Wu K, Sherry AD. A novel europium(III)-based MRI contrast agent. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123(7):1517–1578. doi: 10.1021/ja005820q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ali MM, Woods M, Suh EH, Kovacs Z, Tircso G, Zhao P, Kodibagkar VD, Sherry AD. Albumin-binding PARACEST agents. J Biol In Chem. 2007;12:855–865. doi: 10.1007/s00775-007-0240-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aime S, Barge A, Delli Castelli D, Fedeli F, Mortillaro A, Nielsen FU, Terreno E. Paramagnetic Lanthanide(III) complexes as pH-sensitive chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) contrast agents for MRI applications. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47:639–648. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Terreno E, Cabella C, Carrera C, Castelli DD, Mazzon R, Rollet S, Stancanello J, Visigalli M, Aime S. From spherical to osmotically shrunken paramagnetic liposomes: An improved generation of LIPOCEST MRI agents with highly shifted water protons. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:966–968. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vinogradov E, Zhang S, Lubag A, Balschi JA, Sherry AD, Lenkinski RE. On-resonance low B1 pulses for imaging of the effects of PARACEST agents. J Magn Reson. 2005;176:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoo B, Pagel MD. A PARACEST MRI contrast agent to detect enzyme activity. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14032–14033. doi: 10.1021/ja063874f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shapiro MG, Atanasijevic T, Faas H, Westmeyer GG, Jasanoff A. Dynamic imaging with MRI contrast agents: quantitative considerations. Magn Reson Imag. 2006;24:449–462. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2005.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Querol M, Bogdanov A. Amplification strategies in MR imaging: activation and accumulation of sensing agents (SCAs) J Magn Reson Imag. 2006;24:971–982. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones CK, Schlosser MJ, van Zijl PC, Pomper MG, Golay X, Zhou J. Amide proton transfer imaging of human brain tumors at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:585–592. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun PZ, Zhou J, Sun W, Huang J, van Zijl PCM. Delineating the Boundary Between the Ischemic Penumbra and Regions of Oligaemia Using pH-weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging (pHWI) J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1129–1136. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jokivarsi KT, Grohn HI, Grohn OH, Kauppinen RA. Proton transfer ratio, lactate, and intracellular pH in acute cerebral ischemia. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57:647–653. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bryant RG. The dynamics of water-protein interactions. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1996;25:29–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.25.060196.000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guivel-Scharen V, Sinnwell T, Wolff SD, Balaban RS. Detection of proton chemical exchange between metabolites and water in biological tissues. J Magn Reson. 1998;133:36–45. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1998.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou J, Payen J, van Zijl PCM. The interaction between magnetization transfer and blood-oxygen-level-dependent effects. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53:356–366. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hua J, Jones CK, Blakeley J, Smith SA, van Zijl PCM, Zhou J. Quantitative description of the asymmtry in magnetization transfer effects around the water resonance in the human brain. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:786–793. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Zijl PCM, Zhou J, Mori N, Payen J, Mori S. Mechanism of magnetization transfer during on-resonance water saturation. A new approach to detect mobile proteins, peptides, and lipids. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:440–449. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ling W, Regatte RR, Navon G, Jerschow A. Assessment of glycosaminoglycan concentration in vivo by chemical exchange-dependnt saturation transfer (gagCEST) Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 2008;105:2266–2270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707666105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okumura A, Takenaka K, Nishimura Y, Asano Y, Sakai N, Kuwata K, Era S. The characterization of human brain tumor using magnetization transfer technique in magnetic resonance imaging. Neurol Res. 1999;21:250–254. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1999.11740927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun PZ, Farrar CT, Sorensen AG. Correction for artifacts induced by B0 and B1 field inhomogeneities in pH-sensitive chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:1207–1215. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou J, Wilson DA, Sun PZ, Klaus JA, van Zijl PCM. Quantitative description of proton exchange processes between water and endogenous and exogenous agents for WEX, CEST, and APT experiments. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51:945–952. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pomper MG, Port JD. New techniques in MR imaging of brain tumors. Magn Reson Imag Clin N Am. 2000;8:691–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stadnik TW, Chaskis C, Michotte A, Shabana WM, van Rompaey K, Luypaert R, Budinsky L, Jellus V, Osteaux M. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of intracerebral masses: comparision with conventional MR imaging and histologic findings. AJNR AM J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:969–976. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sinha S, Bastin ME, Whittle IR, Wardlaw JM. Diffusion tensor MR imaging of high-grade cerebral gliomas. AJNR. 2002;23:520–527. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu S, Ahn D, Johnson G, Law M, Zagzag D, Grossman RI. Diffusion-tensor MR imaging of intracranial neoplasia and associated peritumoral edema: Introduction of the tumor infiltration index. Radiology. 2004;232:221–228. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2321030653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oh J, Cha SM, Aiken AH, Han ET, Crane JC, Stainsby JA, Wright GA, Dillon WP, Nelson SJ. Quantitative apparent diffusion coefficients and T2 relaxation times in characterizing contrast enhancing brain tumors and regions of peritumoral edema. J Magn Reson Imag. 2005;21:701–708. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burger PC, Heinz ER, Shibata T, Kleihues P. Topographic anatomy and CT correlations in the untreated glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurosurg. 1988;68:698–704. doi: 10.3171/jns.1988.68.5.0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Segall HD, Destian S, Nelson MD. CT and MR imaging in malignant gliomas. In: Apuzzo MLJ, editor. Malignant cerebral glioma. Park Ridge, IL: American Association of Neurological Surgeons; 1990. pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ross BD, Higgins RJ, Boggan JE, Knittel B, Garwood M. 31P NMR spectroscopy of the in vivo metabolism of an intracerebral glioma in the rat. Magn Reson Med. 1988;6:403–417. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910060406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maintz D, Heindel W, Kugel H, Jaeger R, Lackner KJ. Phosphorus-31 MR spectroscopy of normal adult human brain and brain tumors. NMR Biomed. 2002;15:18–27. doi: 10.1002/nbm.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]