Abstract

Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors are members of the G-protein coupled receptor superfamily that are expressed in and regulate the function of neurons, cardiac and smooth muscle, glands, and many other cell types and tissues. The correct trafficking of membrane proteins to the cell surface and their subsequent localization at appropriate sites in polarized cells are required for normal cellular signaling and physiological responses. This review will summarize work on the synthesis and trafficking of muscarinic receptors to the plasma membrane and their localization at the cell surface.

Keywords: muscarinic, acetylcholine, MDCK, epithelial, neuron, trafficking, localization, glycosylation, GPCR, membrane protein synthesis

1. Introduction

The proper trafficking of proteins to and from the cell surface is essential for normal physiological responses. Aberrant targeting of membrane proteins in polarized cells can result in human disease. For example, mistargeting of the low density lipoprotein receptor in hepatocytes is responsible for hypercholesterolemia in some patients (Koivisto et al., 2001). Mistargeting of Gprotein coupled receptors (G-PCRs) is known to result in disease states. The missorting of rhodopsin in retinal cells can result in retinitis pigmentosa and blindness (Deretic et al., 2005). Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus is the inability of the kidney to concentrate water caused by vasopressin receptor mistargeting in the kidney epithelia (Tan et al., 2003), and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism is a result of missorting of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor (Knollman et al., 2005).

There are five subtypes of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChR) which are products of distinct genes and are members of the (GPCR superfamily (Wess, 1996; Nathanson, 2000). In general, the M1, M3, and M5 receptors activate phospholipase C (PLC), using pertussis toxin-insensitive G-proteins of the Gq family but do not inhibit adenylyl cyclase, and the M2 and M4 receptors inhibit adenylyl cyclase (using pertussis toxin-sensitive G-proteins of the Gi/Go family) but do not stimulate PLC. This specificity is not absolute, however, and M2 and M4 receptors can activate PLC when expressed at high levels in certain cell types due to the release of βγ subunits from Gi/Go (Ashkenazi et al., 1987; Tietje et al., 1990; Katz et al., 1992). Furthermore, both Gi- and Gq-coupled mAChR can couple to Gs to stimulate adenylyl cyclase activity (Migeon and Nathanson, 1994). Muscarinic receptors can regulate ion channels not only through the actions of second messengers but also through the direct regulation of ion channels by activated G-protein subunits (Wickman and Clapham, 1995; Herlitze et al., 1996; Nemec et al., 1999). mAChR can also cause both the endocytosis (Nesti et al., 2004) or insertion into the surface membrane (Singh et al., 2004; Cayouette et al., 2004) of a variety of ion channels. mAChR can also regulate other signal transduction pathways which have diverse effects on cell growth, survival, and physiology, such as the mitogen-activated protein kinases, phosphoinositide-3-kinase, RhoA, and Rac1 (Nathanson, 2000; Marinissen and Gutkind, 2001). The ability of signaling pathways to interact can lead to many complicated regulatory pathways (Nathanson, 2000).

Muscarinic receptors are present in neurons in the central and peripheral nervous systems, cardiac and smooth muscles, secretory glands, and many other cell types and tissues as well. Analysis of the function of individual mAChR subtypes has been greatly aided by the use of mutant mice lacking one or more mAChR genes (reviewed in Wess, 2004; Matsui et al., 2004; Abrams et al., 2006; Eglen, 2006; Wess et al., 2007).

This review will focus on the regulation of newly synthesized muscarinic receptor trafficking to and their localization at the cell surface.

2. Muscarinic receptor synthesis

2.1 A brief introduction to membrane protein synthesis

The transport pathways used by proteins destined for the plasma membrane have been extensively studied for many years. Membrane proteins are synthesized on ribosomes on the rough endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and are generally transported via the Sec61 translocase through and into the ER membrane, followed by transit through the Golgi and delivery to the cell surface (Rapoport, 2007). Multispanning proteins such as GPCR must have signals that allow multiple transmembrane domains to be oriented correctly. Proteins that interact with and presumably are involved in translocation of specific transmembrane domains have been identified for the GPCRs opsin and the neurotensin receptor (Meacock et al., 2002). Many membrane proteins are glycosylated. N-linked-glycosylation on asparagines occurs cotranslationally almost as soon as the nascent polypeptide enters the ER, where initial trimming of the high mannose carbohydrate core occurs. Further trimming and processing occurs in a series of distinct steps in specific regions of the Golgi. O-linked sugars and proteoglycans are also added in the Golgi. O-linked glycosylation occurs in the Golgi by the addition of N-acetylgalactosamine to serines and threonines. Glycosylation has many potential functions, and can, depending on the protein in question, affect ligand binding, protein stability, targeting, processing, and protein-protein interactions (Ohtsubo and Marth, 2006).

2.2. Synthesis and transport of mAChR to the cell surface

The ability of agonist treatment to cause increased receptor degradation and thus decrease steady state receptor levels allowed the first studies on rates of mAChR synthesis by examination of the recovery of mAChR following recovery from agonist-induced downregulation. Total muscarinic receptor numbers in neuroblastoma cells, chick heart cells, and pancreatic acinar cells in culture gradually increased after agonist removal in a cylcoheximide sensitive fashion, returning back to control levels over 12–20 hours. Recovery was blocked by treatment with the protein synthesis inhibitor cylcoheximide, consistent with but not proving that these receptors represented newly synthesized proteins (Klein et al., 1979, Taylor et al., 1979; Galper and Smith, 1980; Hootman et al., 1986). Hunter and Nathanson (1984) took advantage of the ease of manipulation of the chick embryo in ovo to look at the recovery of cardiac mAChR after down regulation in vivo. Receptor number returned to control values over ~14 hours in a cylcoheximide -sensitive fashion. Hunter and Nathanson (1986) found that the recovery of total cellular mAChR (measured using the membrane-permeable antagonist [3H]quinuclidinyl benzilate, QNB) and cell surface mAChR (measured using the membrane-impermeable antagonist [3H]-N-methyl-scopolamine, NMS) occurred with a similar 14 hour time course in cultured chick heart cells after receptor downregulation. Ray et al. (1989) reported that mAChR recovery following downregulation in neuronal cells was blocked by treatment with monensin and nigericin, which interfere with Golgi transport, and with the microtubule inhibitor nocodazole.

While studies examining receptor recovery following agonist-induced downregulation provide information on the synthesis of receptors in cells treated with agonist for long periods of time, they do not necessarily provide information on the rates of receptor synthesis in nonstimulated (i.e., non-agonist treated) cells. Agonist stimulation will of course lead to changes in multiple second messenger pathways and changes in immediate early gene expression. Indeed, long -term agonist exposure has been reported to cause changes in the levels of mRNAs encoding specific mAChR subtypes, although these changes can be celltype specific and do not occur in all cell types (Fukamauchi et al., 1991; Habecker and Nathanson, 1992; Habecker et al., 1993; Lenz et al., 1994; Goin and Nathanson, 2002).

Hunter and Nathanson (1986) compared the rate of recovery of mAChR in cultured heart cells from long-term agonist-induced downregulation and after receptor inactivation with the affinity alkylating antagonist propylbenzilylcholine mustard (PrBCM). Muscarinic receptor expression on the cell surface after downregulation returned to control values in ~14 hr., while 20–24 hr. was required following affinity alkylation. Goin and Nathanson (2002) used immunoprecipitation with subtype specific antibodies to determine the rate of reappearance of newly synthesized mAChR in cultured chick retinal cells after treatment with either carbachol or PrBCM. While the M2 and M4 receptors recovered to similar extents and with similar times courses after either carbachol or PrBCM treatment (> 85% recovery after 20–24 hr.), the M3 receptor exhibited recovery to near control levels only after PrBCM treatment but not after carbachol treatment. Thus, long-term agonist treatment may not only cause increased receptor degradation but may also change the subsequent rate of receptor synthesis.

Alkylation with PrBCM is thought not to affect mAChR synthesis and thus has been used for determination of the rate constant for synthesis in kinetic analyses of mAChR trafficking between intracellular compartments (Koenig and Edwardson, 1994). Using this method, Koenig and Edwardson (1996) showed that the M3 and M4 receptors when stably expressed at similar levels in CHO cells had a three-fold difference in the rate of reappearance of new receptors at the cell surface. Interestingly, SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells endogenously express low levels of M3; when expressed as a percentage of the mAChR on the cell surface, the rate of delivery of M3 was similar to that determined in transfected CHO cells.

Sawyer et al. (2006) used a novel strategy termed regulated secretion-aggregation (RPD™) to measure the rate of synthesis of the M1 receptors in transiently transfected CHO cells. A conditional aggregation domain, consisting of four tandem mutated FKBP12 binding domains, and an intervening furin cleavage site were fused to the N-terminal of M1, which blocked plasma membrane delivery due to aggregation of the mAChR and retention in the ER. Addition of a ligand for the FKBP12 domain resulted in disaggregation and release of the mAChR from the ER, and subsequent cleavage by the trans-Golgi protease furin allowed transport of the near-native M1 receptor to the cell surface. Muscarinic receptors began to appear at the cell surface within 30 minutes of the release from the ER. In the continued presence of the FKBP12 ligand, mAChR expression on the cell surface peaked at ~ 17 hours and then declined, consistent with a model for trafficking of an initially large pool of receptors which then decays as the steady state level of intracellular receptors is obtained. The kinetic data was consistent with a model where the rate of exit of receptor from the ER is equal to the rate of internalization from the plasma membrane. As these authors point out, while this method allows for the synchronized release of receptor which was trapped in the ER, the accumulation of aggregated mAChR in the ER could affect receptor transcription or synthesis. In light of the many changes in cellular biosynthetic pathways that occur in response to ER stress (Zhao and Ackerman, 2006; Ron and Walter, 2007), it seems important to determine if the use of the RPD™ technology alters the kinetics of membrane protein synthesis.

The efficiency of transport of mAChR to the cell surface appears to depend critically on both receptor subtype and the cell type which expresses the receptor. Galper et al. (1982b) found that the number of total cellular mAChR binding sites (measured using [3H]QNB) was the same as the number of cell surface mAChR (measured using [3H]NMS), indicating that there was not a significant number of intracellular receptors in non-agonist stimulated cells. Scherer and Nathanson (1989) reported that the cloned M1 and M2 receptors when expressed in Y1 adrenal cells were expressed essentially all on the cell surface. Tolbert and Lameh (1996) used confocal microscopy to determine that epitope-tagged M1 were mostly at the cell surface of HEK cells, although some cells exhibited some cytoplasmic staining. M2 receptors in CHO cells were shown by similar methods to be also essentially exclusively on the cell surface (Tsuga et al., 1998). In PC12 cells, the endogenously expressed M4 receptor and transfected M1 receptors are detected by immunocytochemistry predominantly on the cell surface (Volpicelli et al., 2001; McClatchy et al., 2006). As discussed in detail below, while the M2 and M3 receptors are expressed almost exclusively on the cell surface of polarized MDCK epithelial cells (albeit in different membrane domains), significant amounts of the M1 and M4 receptors are found intracellularly (Nadler and Nathanson, 2001; Chmelar and Nathanson, 2006; Shmuel et al., 2007).

Differential distributions of the receptors on the plasma membranes can also be found in the intact nervous system. In the striatum, the M4 receptor is localized predominantly at the cell membrane of medium spiny neurons but is mostly cytoplasmic in cholinergic interneurons (Bernard et al., 1999). In the cholinergic neurons of the nucleus basalis magnocellularis, 41% and 68% of the M2 receptors were found on the plasma membrane of cell bodies and dendrites, respectively, with the remainder in various intracellular compartments; 78% of the M2 receptors in the cholinergic terminals of these neurons in the frontal cortex were on the plasma membrane. The proportions of intracellular and plasma membrane receptors change with age (Decossas et al., 2003, 2005). In the ventral tegmental neurons, M2 receptors were found mainly in intracellular membranes of somata and proximal dendrites, suggesting that the receptors are undergoing significant amounts of local synthesis, transport and/or internalization. In contrast, the mAChR was mainly localized to the plasma membrane of distal dendrites and axons (Garzon and Pickel, 2006).

These differences between the proportions of mAChR found on the cell surface suggest that there may be chaperones which can regulate the synthesis, trafficking and/or transport of the receptors in a celltype and receptor subtype-specific manner. Relatively few proteins have been identified which interact with newly synthesized muscarinic receptors or regulate their biosynthetic trafficking. The small G-protein ARF6, which has previously been implicated in regulation of mAChR internalization, has also been implicated in biosynthesis of the M2 and other GPCR. Overexpression of a constitutively active ARF6 has been reported to result in decreased exit of the M2 receptors from the ER to the Golgi (Madziva and Birnbaumer, 2006), although additional work demonstrating a role of endogenous ARF6 in receptor processing is required to confirm this conclusion. DRiP78 is an ER membrane protein which interacts with a hydrophobic motif in the carboxy terminal of the D1 dopamine receptor to regulate its export from the ER; overexpression of DRiP78 also regulates M2 receptor cell surface expression (Bermak et al., 2001).

Both homodimerization and heterodimerization has been shown to be required for transport of some GPCR to the cell surface. Heterodimerization of the GABAB1 and GABAB2 receptors is required to occlude an ER retention signal in the C-terminal of GABAB1 receptor and thus allow its transport to the cell surface (Calver et al., 2001: Paggano et al., 2001). Homodimerization of the β2-adrenergic receptor appears to be important for ER export and trafficking to the cell surface (Salahpour et al., 2004). A number of studies have shown that various subtypes of mAChR can form both homodimers and heterodimers, and dimerization has been reported to affect agonistinduced downregulation of the mAChR (Zeng and Wess, 1999; Novi et al., 2004, 2005; Goin and Nathanson, 2006). The role if any of dimerization in the trafficking of newly synthesized mAChR to the cell surface has not been determined.

2.3 Receptor Glycosylation

Studies on purified cardiac mAChR demonstrated that they were highly glycosylated (Peterson et al., 1986), and the deduced amino acid sequences of all five cloned receptors contain multiple sites for N-linked protein glycosylation. Liles and Nathanson (1986) determined the effects of treatment with tunicamycin, which inhibits the initial step in N-linked glycosylation, on mAChR expression in N1E-115 neuroblastoma cells, which have been reported to express primarily the M4 receptor. Tunicamycin treatment resulted in a large decrease in cell surface mAChR number (measured using [3H]NMS) but only a modest decrease in total cellular mAChR number (measured using [3H]QNB). While tunicamycin did not affect the extent or kinetics of agonist-induced down regulation, it significantly inhibited the reappearance of newly synthesized mAChR after agonist-induced downregulation. These results indicate that inhibition of protein glycosylation interferes with the normal synthesis, transport, insertion, and/or maintenance of mAChR at the cell surface, but do not distinguish between a requirement for glycosylation of the receptor itself or some other component of the biosynthetic process. This inhibitory effect of tunicamycin is not obligatory, however, as Hootman et al. (1990) reported that tunicamycin treatment had only minor effects on the recovery of mAChR (presumably M3) after agonist-induced downregulation of pancreatic acinar cells.

van Koppen and Nathanson (1990) used site-directed mutagenesis to determine if glycosylation of the M2 receptor itself was required for receptor expression. The M2 receptor has 3 residues, Asn2, Asn3, and Asn6, which match the consensus sequence for N-linked glycosylation (N-X-S/T, where X can be any amino acid except proline). The 3 sites for N-linked glycosylation, were mutated to all aspartates, all lysines, or all glutamines. While the Lys2,3,6 mutant receptor was poorly expressed, the Asp2,3,6 and Gln2,3,6 receptors were expressed at normal levels at the cell surface and had normal physiological activity. This lack of requirement for glycosylation for mAChR expression and function has been confirmed with other mAChR subtypes using a variety of expression systems (Weill et al., 1999; Zeng et al., 1999; Furukawa and Haga, 2000).

2.4 Functional activity of newly synthesized mAChR

Taylor et al (1979) used the recovery of mAChR from agonist-induced downregulation in N1E-115 neuroblastoma cells to examine the physiological activity of newly synthesized mAChR. After treatment with agonist to induce receptor degradation and then agonist removal, mAChR number recovered with an apparent half-time of 6 hours, but the t1/2 for the recovery of mAChR-mediated stimulation of cGMP synthesis was approximately 16 hours. While this study determined the time course for the recovery of total mAChR binding sites in membrane homogenates and not the rate of appearance of mAChR on the cell surface, this work suggested that newly synthesized mAChR may not be fully able to couple to physiological responses.

Hunter and Nathanson (1984) used the chick embryo system described above to examine responsiveness of newly synthesized cardiac mAChR in vivo. They found that there was a significant lag in the recovery of both the mAChR-mediated negative chronotropic response of isolated atria and mAChR-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase in membrane homogenates compared to the recovery of mAChR binding sites. While mAChR number returned to control values by 14 hours after atropine reversal of mAChR downregulation, a greater than 10-fold higher concentration of carbachol was required to mediate both the negative chronotropic and cyclic nucleotide responses even at 20 hours compared to controls. The sensitivity of mAChR signaling increased with continued incubation without further increases in mAChR number, so that less than 3-fold more carbachol was required by 28 hours (Hunter and Nathanson, 1984). There were no differences in agonist binding, guanine nucleotide sensitivity of agonist binding, or direct guanine nucleotide-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase at control, 20, and 28 hour time points, suggesting that the decreased functional coupling was not due to impaired mAChR-Gi or Gi-adenylyl cyclase interactions.

Hunter and Nathanson (1986) subsequently showed that the newly synthesized mAChR which reappear after recovery from down-regulation in cultured cardiac cells also exhibited diminished ability to mediate both receptor-mediated increases in potassium permeability and inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity. The muscarinic receptors which reappear following affinity alkylation of the mAChR with PrBCM also exhibited diminished functional responsiveness, so that the diminished physiological responsiveness does not result from a non-specific effect of agonist treatment on cell function. While the recovery of receptor number required proteins synthesis, the increases in functional responsiveness which occurred after receptor number returned to control levels after both agonist and PrBCM treatment did not require further de novo protein synthesis. Ikegaya and Nathanson (1993) showed that recombinant M2 receptors expressed in stably transfected cells also exhibited diminished functional activity after recovery from affinity alkylation. The decreased physiological responsiveness both in the cultured cardiac cells and in the transfected cells also did not appear to be due to altered G-protein expression or function. There did not appear to be major structural differences between the functionally active and impaired mAChR, as [3H]PrBCM-alkylated receptors from cardiac cells had similar migration patterns after both SDS and isoelectric focusing gel electrophoresis. While the molecular basis for this lag in functional responsiveness has not been determined, the diminished physiological sensitivity of newly synthesized mAChR could result from a minor modification of the receptor, a delay in the association of the receptor with a scaffolding protein required for signaling, or a change in an as yet unidentified member of the receptor signal transduction system.

In contrast to these results, there have been reports suggesting that mAChR acquire normal functional activity upon synthesis. Galper et al, (1982a) reported that mAChR number and mAChR-mediated stimulation of potassium permeability in chick cultured cardiac cells recovered simultaneously following down-regulation. Haddad et al. (1995) reported that newly synthesized M2 receptors which reappeared following PrBCM treatment of HEL 229 cells exhibited normal mAChR-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity. However, because these studies used a single saturating concentration of agonist, quantitative differences in the dose-response curves would not have been observed in these experiments. Goin and Nathanson (2002) found that the dose-response curve for mAChR mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity 24 hrs after recovery from agonist-induced down regulation in chick retinal cultures were identical to controls, but since the levels of M2 and M4 receptors had returned to normal by 16 hours, it is likely that a delay in functional responsiveness, if it did occur, would not have been observed by the 24 hour time point.

3. Localization of mAChR in cells and tissues

The physiological signals that a receptor can produce depends not only on which G-proteins it can functionally interact with but also on where in a cell that receptor is localized. There have been a number of reports suggesting the differential subcellular localization of specific mAChR subtypes in a variety of cell types both in the nervous system and in a variety of nonneuronal polarized cells. A caveat in the analysis of the localization of low abundance membrane proteins such as the mAChR (and other GPCR) by immunocytochemical techniques is that rigorous controls are required to ensure specificity of the antibodies. We have found that antibodies which are highly specific by immunoblot and immunoprecipitation analyses for a single mAChR can be completely unsuitable for immunocytochemistry (Hamilton and Nathanson, unpublished). As Saper (2005) has pointed out, the common control of blockade of staining by excess immunogen does not ensure specific staining in immunocytochemical experiments, and the most convincing controls require comparison of staining of tissues from wildtype and knockout animals or of transfected and nonexpressing untransfected cells (e.g., Hamilton et al., 1997; McKinnon et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 2002; Duttaroy et al., 2002). Despite these concerns, functional and immunocytochemical analyses have provided strong evidence that specific mAChR subtypes can be localized to discrete regions of the cell surface in a variety of cell types‥

3.1 Oocytes

Muscarinic receptors activate a calcium-sensitive chloride channel in Xenopus oocytes, and Kusano et al. (1982) first reported that oocytes did not exhibit symmetrical responses to muscarinic agonists. Oron et al. (1988) found that the distribution of responsiveness of endogenous muscarinic receptors differed from the response profile of oocytes expressing exogenous mAChR after injection of crude brain mRNA. Mateus-Leibovitch et al. (1990) reported that the responses of endogenously expressed mAChR in Xenopus oocytes were asymmetrically distributed, with the oocytes falling into two groups with different responses. In “common” oocytes, the vegetal hemisphere exhibited a rapid transient depolarizing current that was somewhat greater than that mediated by agonist application to the animal pole, while the animal pole exhibited a greater slow prolonged response than did the vegetal pole. These differences, however, were relatively small, and of questionable statistical significance. In contrast, a population of “variant” oocytes exhibited a dramatically enhanced (>5-fold) rapid depolarization when ACh was exposed to the animal pole compared to the vegetal pole. These differences were reflected in differences in the distribution of mAChR binding sites measured using [3H]QNB binding: there was a modest increase in mAChR binding sites on the animal compared to the vegetal pole on “common” oocytes, but > 5-fold more mAChR on the animal compared to the vegetal pole of the “variant” oocytes.” This differential distribution was confirmed by ligand binding to 50 µm sections of the two types of oocytes. Davidson et al. (1991) used a combination of pharmacological analyses and antisense oligonucleotides to conclude that the M1 receptors were preferentially localized to the animal poles of the “variant” oocytes, while the M3 receptors were relatively uniformly distributed in the “common” oocytes”.

3.2 Acinar cells

Activation of muscarinic receptors in lacrimal and pancreatic acinar cells results in the secretion of fluid and protein constituents of tears and of digestive enzymes, respectively. Activation of mAChR in lacrimal acinar cells causes the release of intracellular calcium which is initiated at the luminal domain of the cells (Tan et al., 1992). This study did not, however, determine if this was due to restriction of the mAChR to the luminal domain or if the receptors were uniformly distribution but with subcellular localization of a downstream signalling component. Turner et al. (1998) reported that a parotid acinar-line cell line only exhibited changes in transmembrane ion flux when muscarinic agonists were applied basolaterally but not apically. The polarized signaling of acinar mAChR has been most extensively studied in pancreatic acinar cells. Muscarinic receptor-mediated Ca2+ release is initiated at the secretory (apical pole) and then spreads towards the basal pole (Toescu et al., 1992; Shin et al., 2001). Ashby et al. (2003) used patch- clamp recordings with electrodes containing photoactivatable caged carbachol to show that stimulation of basal mAChR could result in calcium signaling at the apical pole, although these authors did not test the effects of apically applied agonist. Shin et al. (2001) and Li et al. (2004) used immunocytochemistry to localize the M3 receptors to the lateral border in the apical domain and to show that it colocalized with the IP3 receptor, although the suitability of the anti- M3 antibody used for the localization by immunocytochemistry was not tested using the rigorous criteria of Saper (2005). Li et al. (2005) used a two patch electrode mapping technique to show that the apical pole was much more sensitive to muscarinic stimulation than the basal pole, consistent with the apical localization detected by immunocytochemistry.

3.3 Intestinal and lingual epithelial cells

Cholinergic receptors regulate ion transport across intestinal epithelial cell membrane and thereby affect intestinal water movement. Activation of muscarinic receptors increases Cl− secretion from the apical membrane of intestinal epithelia cells and K+ efflux from the basolateral membrane; the effects on both potassium and chloride movements are mediated by increases in intracellular Ca2+ (see Hirota and McKay, 2006a, for review). Muscarinic receptors also increase the trafficking of the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter NKCC1 both to and from the basolateral membrane (Reynolds et al., 2007).

Both binding and pharmacological studies indicate that the main subtype of mAChR in rat and human intestinal epithelial cells is the M3 receptor with perhaps a minor contribution from the M1 receptor (Kopp et al., 1989; Dickinson et al., 1992; O’Malley et al., 1995). However, studies with gene-targeted mice indicate that the M1 and perhaps other subtypes have a more dominant role, at least in that species (Haberberger et al., 2006; Hirota and McKay, 2006b.) Muscarinic agonists only produce electrophysiological responses when applied to the basolateral membrane and not the apical membrane of intestinal epithelial cells (Dharmsathaphorn and Pandol, 1986). The polarization of functional responsiveness does not distinguish between specific subcellular localization of the receptors or uniform receptor distribution with localization of downstream signaling components. Reynolds et al. (2007) used immunocytochemistry to localize the M3 receptor to the basal membrane of human intestinal epithelium. In contrast, the Gαq and Gα11 G-protein subunits, which mediate the mAChR-mediated calcium signaling in epithelial cells, are not polarized and are uniformly distributed throughout the cells (Cummins et al., 2002).

The activation of basolateral mAChR also activates additional signaling cascades in intestinal epithelial cells. Muscarinic agonists activate the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor (which is also localized to the basolateral membrane) via metalloproteinase-mediated basolateral secretion of transforming growth factor-α. This activation of EGF receptors results in activation of ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase, p38 kinase, and focal adhesion kinase (McCole et al., 2002; Keely and Barrett, 2002; Calandrella et al., 2005). Activation of the ERK and p38 pathways act independently in an apparent feedback fashion to inhibit mAChR-mediated chloride secretion, while activation of focal adhesion kinase provides a potential mechanism for regulation of cell adhesion and migration. Thus, the basolaterally localized mAChR utilize multiple mechanisms to regulate the physiology of intestinal epithelial cells.

Muscarinic agonists evoke electrophysiological changes in canine lingual epithelial cells only when applied to the serosal (basolateral) but not mucosal (apical) membrane (Simon and Baggett, 1992). The authors presented data suggesting that the change in membrane conductance was due to inhibition of K+ flux due to mAChR-mediated decreases in intracellular cAMP levels. The subtype and subcellular localization of the mAChR responsible for these effects was not identified.

3.4 MDCK cells

Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells represent a widely used model system for the study of intracellular protein transport and trafficking. When grown to confluency, MDCK cells assume a highly polarized topography, with the apical and basolateral membranes separated by tight junctions. The apical and basolateral membranes differ in their composition of both membrane proteins and membrane phospholipids, and MDCK cells have been used to identify both targeting signals and the transport pathways responsible for specific cellular sorting (Rodriquez-Boulan et al., 2005; Ellis et al., 2006). Two strains of MDCK cells are in wide use. The surface area of the basolateral domain of strain I cells is approximately 4 times larger than the surface area of the apical domain, while the surface areas of the apical and basolateral domains of strain II cells are equal (Butor and Davous, 1992).

Mohuczy-Dominiak and Garg (1992a, 1992b) showed that MDCK strain I cells expressed a fairly high density of mAChR binding sites that had a M3- like specificity in ligand binding assays. In addition, muscarinic agonists mediated both activation of PLC and inhibition of adenylyl cyclase. Both responses exhibited a pharmacological specificity characteristic of the M3 receptor and were blocked by pretreatment with pertussis toxin, although approximately 20-fold higher concentrations of toxin were required to block the adenylyl cyclase response compared to the PLC response. While these studies did not report if muscarinic receptor expression and responsiveness were polarized (i.e., specific to the basolateral or apical domain), Luo et al. (1992) found that both the apical and basolateral domains exhibited a calcium transient in response to carbachol stimulation. Receptor desensitization was domain-specific: while both apical and basolateral calcium responses were greatly diminished after reapplication of carbachol to the domain that was originally stimulated, carbachol stimulation of either the apical or basolateral domain was not diminished by pretreatment of the opposite domain. In addition, apical but not basolateral mAChR stimulation could cause heterologous desensitization of the bradykinin-evoked Ca2+ response localized to the basolateral domain.

Nadler et al. (1999) took advantage of the equal surface areas of the apical and basolateral domains of MDCK strain II cells to determine if there was polarization of mAChR expression and functional responsiveness. MDCK II cells plated at high density on Transwell filters formed tight seals within 2 days of plating; ligand binding with [3H]NMS showed equal numbers of mAChR on the apical and basolateral domains at this time. Three days later, there were significantly more mAChR binding sites on the basolateral domain compared to the apical domain, and the basolateral density remained 2.3–2.7 fold higher than the apical density for the next week and a half in culture. Domain-specific cell surface biotinylation followed by strepavidin-agarose precipitation of [3H]QNB labeled receptors confirmed that the density of mAChR was significantly higher on the basolateral compared to the apical membrane.

There was also polarization of muscarinic responsiveness. Muscarinic agonists evoked inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity when applied to the apical domain but not to the basolateral domain. Both apical and basolateral mAChR evoked similar increases in intracellular Ca2+ levels, but treatment with pertussis toxin revealed an additional asymmetry in this response. Pertussis toxin completely blocked apical mAChR-mediated Ca2+ signalling, but only caused partial blockade of basolateral mAChR signaling. Single cell analyses demonstrated that this partial blockade was due to a heterogeneous sensitivity of the cells to pertussis toxin: while nearly all non-toxin treated cells responded to basolateral carbachol, only approximately half of the toxin treated cells exhibited a Ca2+ response to basolateral mAChR stimulation.

Nadler et al. (1999) also examined the subtypes of mAChR endogenously expressed in MDCK II cells. While subtype-specific antibodies against the M1, M2, M3, and M4 did not appear to detect the MDCK cell mAChR, RT-PCR detected mRNA for M4 and M5 but not other subtypes. Combined with the results of the functional analyses, these results suggest that the M4 receptor is located on both the apical and basolateral domains (thus mediating inhibition of apical adenylyl cyclase and both apical and basolateral pertussis-sensitive Ca2+ increases) and the M5 receptor is localized to the basolateral domain in a subset of cells (thus mediating pertussis-insensitive Ca2+ increases). However, this does not explain the lack of basolateral inhibition of adenylyl cyclase. If the M4 receptor is indeed in both the apical and basolateral domains, then perhaps there is polarized expression of G-proteins or adenylyl cyclases which is responsible for this lack of response. This conclusion also appears to conflict with the observation that transfected M4 receptors are preferentially expressed on the basolateral surface (see below). Further analyses of endogenous mAChR distribution using additional subtype-specific antibodies or pharmacological analyses and of the distribution of G-proteins and adenylyl cyclase isozymes may resolve this issue.

Nadler and Nathanson (2001) used the transfection of cloned mAChR tagged with the FLAG epitope into MDCK cells and confocal microscopy to obtain further information on the intracellular targeting of mAChR and to determine if mAChR possessed sorting signals which could direct a specific subtype to specific regions of the cell surface. Initial experiments demonstrated that the M2 and M3 receptors were localized to different domains at steady state, with the M2 highly enriched on the apical membrane and the M3 receptors localized to the basolateral domain. The M1, M4, and M5 receptors appeared to have non-polarized distributions with labeling appearing throughout the cells when immunocytochemistry was performed on permeabilized cells, but subsequent studies examining cell surface staining of non-permeabilized cells showed that the M1 and M4 receptors were also localized on the cell surface to the basolateral domain (Chmelar and Nathanson, 2006; Shmuel et al., 2007).

Nadler and Nathanson (2001) then used a chimeric receptor approach to identify regions of the receptors responsible for subcellular targeting. Chimeric receptors between the M2 and M3 receptors which included the N-terminal portion of the third intracellular loop of M3 were sorted to the basolateral domain. A series of receptor constructs which included residues 266–296 from the M3 receptors all exhibited basolateral localization, while a number of chimeric receptors which did not contain this region of M3 were sorted to the apical domain. To ensure that this redirection of targeting was due to the addition of a basolateral targeting sequence from the M3 receptor and not due to the removal of an apical targeting sequence from M2, the Ala266-Gln296 region of M3 was either inserted into the i3 loop of M2 or appended to the carboxyl tail of M2. In both cases, the receptors now exhibited basolateral targeting. These results show that this sequence of the M3 receptors acts as a basolateral targeting sequence in a position-independent manner and is dominant over any apical targeting signals present in the M2 receptor. To test if these M3 targeting signals can act autonomously, that is, if it can act as a basolateral targeting signal for an unrelated protein, the M3 Ala266-Gln296 region was appended to the carboxy terminus of the interleukin-2a receptor (IL-2aR), which is a single transmembrane domain polypeptide with a predominantly apical distribution. The addition of the M3 sequence resulted in a dramatic increase in the basolateral targeting of the IL-2aR, demonstrating that the M3 targeting sequence can indeed confer basolateral targeting to a unrelated protein that is not a member of the GPCR superfamily.

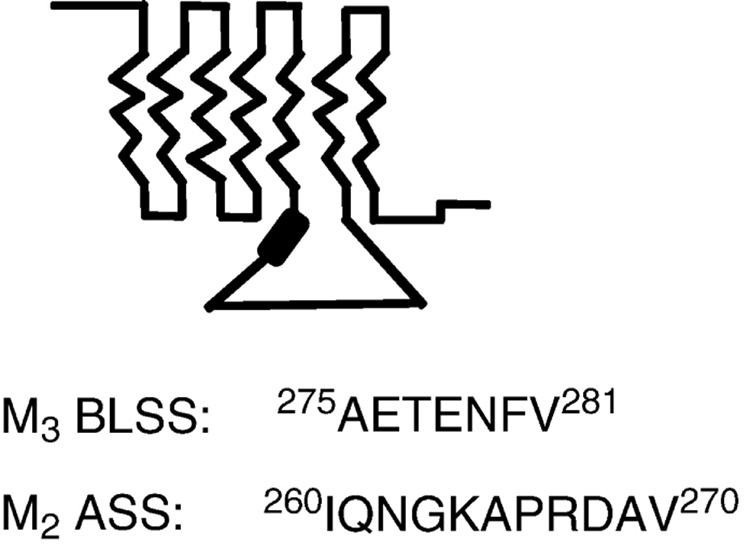

The ability of the M3 targeting sequence to confer basolateral targeting when appended to the M2 carboxy tail facilitated subsequent studies to further define the regions and amino acid residues required for targeting. Nadler and Nathanson (2001) showed a 21 amino acid region, Ser271-Ser291, from the M3 receptor was sufficient to confer basolateral targeting. Iverson et al. (2005) then used a block alanine-scanning mutagenesis approach to identify which portions of this 21 amino acid region were obligatory for basolateral targeting, and followed this with point mutations to identify crucial amino acids. These studies identified Glu276, Phe280, and Val281 as amino acids that were each required for basolateral targeting. A seven amino acid sequence containing these residues, Ala275-Val281, when appended to the C-termini of either the M2 receptor or IL-2aR, was sufficient to redirect these proteins to the apical domain, while mutation of Phe280 to Ala in the seven amino acid sequence caused a lose of basolateral targeting.

This seven amino acid M3 basolateral targeting sequence is : 275AETENFV281. One class of previously identified basolateral targeting sequences contain dihydrophobic residues composed of LL, LI, LV, FL, or ML, sometimes in combination with one or more N-terminal acidic residues (Rodriquez-Boulan et al., 2005). Additional mutagenesis studies showed that mutation of Glu276 to Asp resulted in a loss of basolateral targeting, indicating that glutamate was obligatory and that there was not a general requirement for an acidic amino acid. Single or double mutation of the FV to LV, FL, or LL did not disrupt basolateral targeting. These results suggest that the FV in the M3 receptor acts like a classical dihydrophobic basolateral targeting signal. However, in contrast to the results seen with the native 7 amino acid M3 sequence, mutation of Glu to Asp combined with the LL mutation retained basolateral targeting. Thus, while it is possible that the FV represents another example of the general class of dihydrophobic basolateral targeting sequences, it is clear the requirement for an acidic residue differs between the naturally occurring FV and the LL sorting signals. One can not therefore exclude the possibility that the native .AETENFV sequence represents a different class of sorting signal from that of the mutant ADTENLL basolateral sorting sequence

While these results described above identify Ala275-Val281 as the primary basolateral targeting sequence in the M3 receptor, it is most likely not the only region responsible for basolateral targeting, as a M3 deletion mutant lacking Ala266-Gln296 retained basolateral targeting (Nadler and Nathanson, 2001). The site or sites containing the presumptive secondary basolateral targeting sequences remain to be determined.

Iverson et al. (2005) also used two-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance to determine the solution structure of a 19 amino acid peptide containing this basolateral sorting sequence. The peptide had two regions that had distinct β-turn structures, Thr272-Glu276, and Asn279-Thr284, which create a large negatively charged surface and a large exposed hydrophobic surface, respectively. It is possible, however, that the conformation of this sorting sequence differs in solution from that when it is bound to an interacting protein, as has been shown for the tyrosine-based endocytotic signal In the EGF receptor (Owen and Evans, 1998). Nonetheless, this represents the first solution structure of a GPCR sorting sequence and the first example of a basolateral sorting sequence that has a turn-turn motif.

Chmelar and Nathanson (2006) investigated the sequences and mechanism responsible for targeting the M2 receptor to the apical domain. Because N-glycans can act as apical targeting signals (Urquhart et al., 2005), the sorting of a glycosylation-defective mutant in which the three N-terminal asparagines were mutated to aspartates was determined. The glycosylation-defective mutant receptor still exhibited apical targeting, indicating that N-linked glycosylation is not required for apical targeting of the M2 receptor. A series of chimeric constructs between M2 and the basolateral M4 receptor demonstrated that the third cytoplasmic loop of M2 when substituted into M4 would redirect the receptor to the apical cell surface. Chimeric receptors containing M2 sequences from the amino terminal through the end of transmembrane domain 5 or from the beginning of transmembrane domain 6 to the C-terminus retained basolateral surface expression. To confirm that the third cytoplasmic domain of M2 contains apical targeting information, the entire third cytoplasmic loop was appended to the C-tail of M4. The resulting receptor construct was now localized to the apical surface. Analysis of the targeting of additional constructs showed that two regions of the M2 third cytoplasmic loop could confer apical targeting when appended to M4: an 11 amino acid sequence, Val270-Lys280, and a large region, Lys280-Ser350, which could not be further subdivided because addition of smaller regions to M4 resulted in receptors which were poorly expressed. The importance of both of these sequences in the targeting of the M2 receptor was confirmed by deletion analyses which demonstrated that deletion of both sequences was required for a loss of apical targeting of the M2 receptor.

These results show that, like the M3 basolateral sequence, the M2 apical targeting sequence can act in a position-independent fashion outside of its normal location in the third cytoplasmic loop. In addition, while the M3 basolateral targeting sequence is dominant over the M2 apical sorting sequences, the M2 apical targeting sequences are dominant over whatever targeting signals direct M4 to the basolateral surface. These results are consistent with many others which show that sorting signals can differ in their “strength” or effectiveness resulting in a hierarchy of sorting signals in a given protein (Matter et al., 1992; Jacob et al., 1999; Adair-Kirk et al., 2003). The amino acid sequences of the 7 amino acid basolateral sorting sequence in the M3 receptor and the 11 amino acid apical sorting sequence in the M2 receptor are shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Muscarinic receptor sorting signals. TOP: The approximate location of the targeting signals in both the M2 and M3 receptors is depicted by the thick line in the third cytoplasmic loop. BOTTOM: The amino acid sequences of the basolateral sorting signal in the M3 receptor and the apical sorting signal in the M2 receptor.

Lipid rafts are cholesterol-rich and sphingolipid-rich microdomains that are thought to serve as sorting platforms which concentrate apical proteins into transport vesicles in the trans-Golgi network. Some apical proteins are thought to require association with lipid rafts to achieve correct targeting (Shuck and Simons, 2004). However, when extracted with Triton X-100 and subjected to Opti-Prep™ density gradient centrifugation, the M2 receptor did not exhibit the “flotation” characteristic of a raft-associated protein. As a further test of whether the M2 receptor was localized to lipid rafts, the pentavalent cholera toxin β-subunit (ChTxβ), which can bind to five cell surface GM1 gangliosides and cause co-clustering of raft associated proteins, was used. These clusters can be further aggregated using an anti-ChTxβ antibody, which causes these small clusters to form larger “patches”. Almost all of the M2 receptor did not co-localize with these patches, further confirming the lack of a role for lipid rafts in M2 apical targeting (Chmelar and Nathanson, 2006).

There are multiple mechanisms responsible for the differential targeting of proteins in epithelial cells. Many proteins undergo direct “vectorial” transport to either the apical or basolateral domain. Other proteins are transported to both domains but undergo selective stabilization or endocytosis in one domain. Still other proteins may be transported to one domain but then undergo endocytosis and transport (“transcytosis”) to the surface of the other domain (Rodriquez-Boulan et al., 2005; Ellis et al., 2006). 35S-metabolic labeling and domain-specific biotinylation was used to determine the mechanism responsible for the steady state localization of the M2 receptor on the apical surface. Newly synthesized M2 receptors were first (at 15 minutes) detected only on the basolateral domain, while the majority of receptor at 30 minutes remained basolateral with receptor now detectable on the apical domain as well. By 60 minutes the majority of receptor was now on the apical domain. These results show that the M2 receptor is first transported to the basolateral domain and only subsequently appeared on the apical domain. These results show that transcytosis and not direct vectorial transport or selective stabilization is responsible for the apical targeting of M2 (Chmelar and Nathanson, 2006).

Further support for this hypothesis was obtained by examining the kinetics of appearance of M2 receptor in newly transfected cells (Chmelar and Nathanson, 2006). These studies used a receptor tagged at the amino terminal with FLAG and at the carboxy terminal with green fluorescent protein (GFP), so that both total receptor expression (using GFP fluorescence) and cell surface expression (using immunostaining of nonpermeabilized cells) could be simultaneously monitored. M2 receptor appeared on the cell surface initially only on the basolateral surface, and only subsequently appeared on the apical surface. To confirm that this delayed appearance was due to transcytosis, tannic acid was used to cause domain-specific inhibition of delivery of proteins to the cell surface. Treatment of the apical domain with tannic acid did not disrupt the initial appearance of M2 on the basolateral surface but blocked its subsequence appearance on the apical surface. In contrast. treatment of the basolateral domain with tannic acid blocked the cell surface expression of M2 in both domains and receptors accumulated intracellularly. These results provide strong evidence that the mechanism of apical delivery of the M2 receptor is via transcytosis.

35S-metabolic labeling and domain-specific biotinylation of the M3 receptor in MDCK cells indicates that the M3 receptor undergoes direct vectorial transport to the basolateral domain (Kalaydjian, Nadler, and Nathanson, unpublished). Thus, the M2 and M3 receptors use distinct mechanisms to achieve their polarized distributions in MDCK cells. Both receptors are initially transported to the basolateral domain, but while the M3 receptor remains, the M2 receptor is internalized and then reinserted into the apical membrane surface. The exact step or steps where the two apical sorting sequences in the M2 receptor act remain to be determined.

3.5 Nervous System

Muscarinic receptors are also differentially distributed in neurons. Pharmacological studies initially suggested that the M1 receptor is most commonly (but not uniquely) postsynaptic and that the M2 receptor is located presynaptically (references in Levey et al., 1991). Neuronal growth cone membranes are highly enriched in M2 receptors (Saito et al., 1991), further supporting a presynaptic localization for M2. However, immunocytochemical and gene targeting studies have shown that the localization of muscarinic receptors can be dependent not only on the receptor subtype but on the specific neuron in which a receptor is expressed. A few examples of mAChR localization in different regions of the central nervous system are discussed in the following sections.

3.5.1 Hippocampus

In hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells, the M1 receptor is located in cell bodies and both proximal and distal dendrites. The M1 receptor colocalized with the NR1 subunit of the NMDA receptor, consistent with physiological studies which showed that the M1 receptor potentiated both pharmacologically administered NMDA and synaptically released glutamate (Marino et al., 1998). Immunocytochemistry also showed that the M2 receptor in the CA1 region was primarily presynaptic, although some dendritic staining in the pyramidal layer was also observed. The M2 receptor was found both on cholinergic and non-cholinergic terminals, indicating that it could function both as a cholinergic autoreceptor and a presynaptic heteroreceptor (Rouse et al., 2000). In the perforant pathway synapse on hippocampal granule cells, both lesion and electron microscopic studies demonstrate that the M1 and M3 receptors are postsynaptic and the M2, M3, and M4 receptors are presynaptic (Levey et al., 1995; Rouse and Levey, 1997; Rouse et al., 1998). The celltype-specific localization of the M2 receptor on hippocampal GABAergic interneurons was demonstrated by Hajos et al. (1998), who found that different classes of interneurons expressed the receptor either on somatodendritic or axonal domains.

3.5.2 Striatum

The lack of a unique subcellular localization for a given mAChR subtype can also be seen in the striatum. In rodent striatum, the M1 and M4 receptors are enriched in dendrites of medium spiny neurons and at postsynaptic densities, but M1 is also found in some axon terminals. Anti-M2 receptor antibody primarily labeled axon terminals but also stained some cell bodies and dendrites, while the M3 receptor was in some spiny dendrites and axon terminals (Hersch et al., 1994; Narushima et al., 2007). The M1 receptor was present at higher density in dendritic shafts and cell bodies than in spines, where it appeared to be excluded from synaptic sites (Uchigashima et al., 2007) In primate striatum, both the M1 and the M2 receptors were found in cell bodies, axons, and dendrites, and both receptors were found at synaptic and nonsynaptic sites (Alcantara et al., 2001). The M2 receptor in ventral tegmental neurons are also found in cell bodies, proximal and distal dendrites, and axons, although as noted above, the receptor is mainly on internal membranes in cell bodies and proximal dendrites (Garzon and Pickel, 2006).

3.5.3. Cerebral Cortex

The M2 receptor is found both on the cell bodies and dendrites of cholinergic neurons of the nucleus basalis magnocellularis and their axons which project to the frontal cortex (Decossas et al., 2003). In primate cerebral cortex, both the M1 and M2 receptors were found postsynaptically at asymmetric synapses in dendrites and spines, and the M2 receptor was also present in presynaptic axon terminals (Mrzljak et al., 1993. 1998). In cat visual cortex, postsynaptic M2 receptors were most often on GABAergic neurons and presynaptic M2 receptors were mainly on non-GABAergic nerve terminals (Erisir et al., 2001).

3.5.4 Thalamus

Oda et al. (2007) found M2 on peripheral regions of cell bodies and distal dendrites but not axons or terminals of the rat reticular thalamic nucleus, and the M3 receptor on cell bodies and proximal dendrites, Plummer et al. (1999) compared the distribution of mAChR in rat and cat lateral geniculate nucleus. In rat, the M1 and M3 receptors were on dendrites and cell bodies of thamalocortical cells. The M2 receptor was present on cell bodies, synaptic terminals, axons, and dendrites. No M1 receptor was detected in cat lateral geniculate nucleus, suggesting that there may be species-specific differences in the distribution of mAChR.

3.5.5 Identification of presynaptic mAChR by gene targeting

Studies with knockout (KO) mice have also identified presynaptic localizations of muscarinic receptors in various tissues. Zhang et al. (2002) showed that the M2 receptor was the main presynaptic autoreceptor in hippocampus and cerebral cortex, while the M4 receptor was the main autoreceptor in the striatum. The M2 receptor also acts as a presynaptic inhibitory receptor on motor neuron nerve terminals (Parnas et al., 2005). Fukodome et al. (2004) used M2 KO mice to confirm the immunocytochemical results of Hajos et al. (1998) that presynaptic M2 receptors inhibit GABA release from hippocampal interneurons. Both M2 and M4 receptors mediate inhibition of GABA release from GABAergic afferents onto dorsal horn neurons in the spinal cord, while presynaptic M3 receptors appear to increase GABA release. Surprisingly, both the localization and physiological effects of M2 and M4 on GABA release appear to differ between rat and mouse (Zhang et al., 2005, 2006).

Both the M2 and M4 receptors act as presynaptic inhibitory autoreceptors on myenteric neurons In the ileum (Takeuchi et al., 2005). Different subtypes of mAChR also mediate regulation of catecholamine release in different target organs of the sympathetic nervous system. Both M2 and M3 receptors inhibit norepinephrine in sympathetic terminals in the atria, M2 and M4 receptors inhibit norepinephrine release in the urinary bladder, and M2, M3, and M4 receptors all inhibit release from sympathetic terminals in the vas deferens (Trendelenburg et al., 2003, 2005).

3.5.6 Axonal transport of mAChR

The presence of mAChR in nerve terminals and dendritic spines requires that they be trafficked from the cell body to the distal processes. Laudron (1980) and Wamsley et al. (1981) reported that mAChR would accumulate on both sides of the sites of ligatures of the sciatic, vagus, and splenic nerves, consistent with the transport of the receptors in both the anterograde and retrograde directions. Some of the mAChR in the sympathetic nerves cofractionated on density gradients with vesicles containing norepinephrine and dopamine-β-hydroxylase, consistent with the hypothesis that these represented presynaptic receptors undergoing cotransport with synaptic vesicles. Zarbin et al (1982) used double ligature experiments of the rat vagus nerve to compare mAChR undergoing anterograde and retrograde transported. They found that receptors undergoing anterograde transport (which presumably represented newly synthesized receptors) exhibited high affinity and guanine nucleotide-sensitive agonist binding, while receptors undergoing retrograde transport (which presumably represent receptors that have been internalized from the nerve terminal) exhibited primarily low affinity, guanine nucleotide-insensitive, agonist binding. These results suggest that newly synthesized mAChR may be transported to the nerve terminal in a complex with the G proteins required for their action, while recycled receptors return to the cell body uncoupled from their G-protein.

Since these studies used radioligands for mAChR identification and were done prior to the cloning of the mAChR, it would obviously be of interest to carry out similar studies on the axonal transport of individual mAChR subtypes.

4. Conclusions

There is much that remains to be determined in order to understand the molecular and cellular basis for the regulation of synthesis and localization of mAChR. It is reasonable to assume that there are proteins which are important for the proper folding of newly synthesized receptors and their subsequent transport to the cell surface. The elucidation of the mechanisms responsible for the localization of specific mAChR subtypes at discrete regions of the cell surface and the roles of tissue-specific, subtype-specific, and even (animal) species-specific differences in receptor trafficking and localization should provide not only fascinating basic information on the cell biology of membrane proteins but also may provide insights into human pathophysiological conditions and pharmacotherapeutic interventions for their treatment.

Acknowledgements

I thank the many current and former colleagues and collaborators with whom I have worked. Research in the author’s laboratory has been supported by the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, and the University of Washington.

Abbreviations

- ChTxβ

cholera toxin β-subunit

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptor

- KO

knockout

- mAChR

muscarinic acetylcholine receptor

- MDCK

Madin-Darby canine kidney

- NMS

N-methyl-scopolamine

- QNB

quinuclidinyl benzilate

- PLC

phospholipase C

- PrBCM

propylbenzilylcholine mustard

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abrams P, Andersson KE, Buccafusco J, Chapple C, de Groat WC, Fryer A, Kay G, Laties A, et al. Muscarinic receptors: their distribution and function in body systems, and the implications for treating overactive bladder. Brit J Pharmacol. 2006;148:565–578. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adair-Kirk TL, Dorsey FC, Cox JV. Multiple cytoplasmic signals direct the intracellular trafficking of chicken kidney AE1 anion exchangers in MDCK cells. J Cell Sci. 2003;15:655–663. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcantara AA, Mrzljak L, Jakab RL, Levey AI, Hersch SM, Goldman-Rakic PS. Muscarinic m1 and m2 receptor proteins in local circuit and projection neurons of the primate striatum: anatomical evidence for cholinergic modulation of glutamatergic prefrontostriatal pathways. J Comp Neurol. 2001;434:445–460. doi: 10.1002/cne.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby MC, Camello-Almaraz C, Gerasimenko OV, Petersen OH, Tepikin AV. Long distance communication between muscarinic receptors and Ca2+ release channels revealed by carbachol uncaging in cell-attached patch pipette. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20860–20864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302599200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazi A, Winslow JW, Peralta EG, Peterson GL, Schimerlik MI, Capon DJ, et al. A single M2 muscarinic receptor subtype coupled to both adenylyl cyclase and phosphoinositide turnover. Science. 1987;238:672–675. doi: 10.1126/science.2823384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermak JC, Li M, Bullock C, Zhou QY. Regulation of transport of the dopamine D1 receptor by a new membrane-associated ER protein. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:492–498. doi: 10.1038/35074561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard V, Levey AI, Bloch B. Regulation of the subcellular distribution of m4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in striatal neurons in vivo by the cholinergic environment: evidence for regulation of cell surface receptors by endogenous and exogenous stimulation. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10237–10249. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10237.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butor C, Davoust J. Apical to basolateral surface area ratio and polarity of MDCK cells grown on different supports. Exp Cell Res. 1992;203:115–127. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(92)90046-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calandrella SO, Barrett KE, Keely SJ. Transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor mediates muscarinic stimulation of focal adhesion kinase in intestinal epithelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 2006;203:103–110. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calver AR, Robbins MJ, Cosio C, Rice SQ, Babbs AJ, Hirst WD, et al. The C-terminal domains of the GABA(b) receptor subunits mediate intracellular trafficking but are not required for receptor signaling. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1203–1210. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-04-01203.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayouette S, Lussier MP, Mathieu EL, Bousquet SM, Boulay G. Exocytotic insertion of TRPC6 channel into the plasma membrane upon Gq protein-coupled receptor activation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:7241–7246. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312042200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmelar RS, Nathanson NM. Identification of a novel apical sorting motif and mechanism of targeting of the M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35381–35396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605954200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins MM, O'Mullane LM, Barden JA, Cook DI, Poronnik P. Antisense co-suppression of G(alpha)(q) and G(alpha)(11) demonstrates that both isoforms mediate M(3)-receptor-activated Ca(2+) signalling in intact epithelial cells. Pflugers Arch. 2002;444:644–653. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0856-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson A, Mengod G, Matus-Leibovitch N, Oron Y. Native Xenopus oocytes express two types of muscarinic receptors. FEBS Lett. 1991;284:252–256. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80697-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decossas M, Bloch B, Bernard V. Trafficking of the muscarinic m2 autoreceptor in cholinergic basalocortical neurons in vivo: differential regulation of plasma membrane receptor availability and intraneuronal localization in acetylcholinesterase-deficient and -inhibited mice. J Comp Neurol. 2003;462:302–314. doi: 10.1002/cne.10734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Décossas M, Doudnikoff E, Bloch B, Bernard V. Aging and subcellular localization of m2 muscarinic autoreceptor in basalocortical neurons in vivo. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:1061–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deretic D, Williams AH, Ransom N, Morel V, Hargrave PA, Arendt A. Rhodopsin C terminus, the site of mutations causing retinal disease, regulates trafficking by binding to ADP-ribosylation factor 4 (ARF4) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3301–3306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500095102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dharmsathaphorn K, Pandol SJ. Mechanism of chloride secretion induced by carbachol in a colonic epithelial cell line. J Clin Invest. 1986;77:48–354. doi: 10.1172/JCI112311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson KE, Frizzell RA, Sekar MC. Activation of T84 cell chloride channels by carbachol involves a phosphoinositide-coupled muscarinic M3 receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;225:291–298. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(92)90102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duttaroy A, Gomeza J, Gan JW, Siddiqui N, Basile AS, Harman WD, et al. Evaluation of muscarinic agonist-induced analgesia in muscarinic acetylcholine receptor knockout mice. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:1084–1093. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.5.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eglen RM. Muscarinic receptor subtypes in neuronal and non-neuronal cholinergic function. Auton Autacoid Pharmacol. 2006;26:219–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-8673.2006.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis MA, Potter BA, Cresawn KO, Weisz OA. Polarized biosynthetic traffic in renal epithelial cells: sorting, sorting, everywhere. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291:F707–F713. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00161.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erisir A, Levey AI, Aoki C. Muscarinic receptor M(2) in cat visual cortex: laminar distribution, relationship to gamma-aminobutyric acidergic neurons, and effect of cingulate lesions. J Comp Neurol. 2001;441:168–185. doi: 10.1002/cne.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukamauchi F, Hough C, Chuang DM. Expression and agonist-induced down-regulation of mRNAs of m2- and m3-muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in cultured cerebellar granule cells. J Neurochem. 1991;56:716–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb08210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukudome Y, Ohno-Shosaku T, Matsui M, Omori Y, Fukaya M, Tsubokawa H, et al. Two distinct classes of muscarinic action on hippocampal inhibitory synapses: M2-mediated direct suppression and M1/M3-mediated indirect suppression through endocannabinoid signalling. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:2682–2692. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa H, Haga T. Expression of functional M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor in Escherichia coli. J Biochem (Tokyo) 2000;127:151–161. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galper JB, Dziekan LC, Miura DS, Smith TW. Agonist-induced changes in the modulation of K+ permeability and beating rate by muscarinic agonists in cultured heart cells. J Gen Physiol. 1982a;80:231–256. doi: 10.1085/jgp.80.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galper JB, Dziekan LC, O'Hara DS, Smith TW. The biphasic response of muscarinic cholinergic receptors in cultured heart cells to agonists. J Biol Chem. 1982b;257:10344–10356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galper JB, Smith TW. Agonist and guanine nucleotide modulation of muscarinic cholinergic receptors in cultured heart cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1980;255:9571–9579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garzón M, Pickel VM. Subcellular distribution of M2 muscarinic receptors in relation to dopaminergic neurons of the rat ventral tegmental area. J Comp Neurol. 2006;498:821–839. doi: 10.1002/cne.21082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goin JC, Nathanson NM. Subtype-specific regulation of the expression and function of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in embryonic chicken retinal cell. J Neurochem. 2002;83:964–792. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goin JC, Nathanson NM. Quantitative analysis of homo- and heterodimerization of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in live cells: regulation of receptor down-regulation by heterodimerization. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5416–5425. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507476200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habecker BA, Nathanson NM. Regulation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor mRNA expression by activation of homologous and heterologous receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;8:5035–5038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.5035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habecker BA, Wang H, Nathanson NM. Multiple second messenger pathways mediate agonist regulation of muscarinic receptor mRNA expression. Biochemistry. 1993;32:4986–4990. doi: 10.1021/bi00070a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberberger R, Schultheiss G, Diener M. Epithelial muscarinic M1 receptors contribute to carbachol-induced ion secretion in mouse colon. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;530:229–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad EB, Rousell J, Barnes PJ. Muscarinic M2 receptor synthesis: study of receptor turnover withpropylbenzilylcholine mustard. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;290:201–205. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(95)00072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hájos N, Papp EC, Acsády L, Levey AI, Freund TF. Distinct interneuron types express m2 muscarinic receptor immunoreactivity on their dendrites or axon terminals in the hippocampus. Neuroscience. 1998;82:355–376. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00300-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton SE, Loose MD, Qi M, Levey AI, McKnight GS, Hille B, et al. Disruption of the m1 receptor gene ablates muscarinic receptor-dependent M current regulation and seizure activity in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13311–13316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herlitze S, Garcia DE, Mackie K, Hille B, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Modulation of Ca2+ channels by G-protein beta gamma subunits. Nature. 1996;380:258–262. doi: 10.1038/380258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersch SM, Gutekunst CA, Rees HD, Heilman CJ, Levey AI. Distribution of m1-m4 muscarinic receptor proteins in the rat striatum: light and electron microscopic immunocytochemistry using subtype-specific antibodies. J Neurosci. 1994;14:3351–3363. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-03351.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota CL, McKay DM. Cholinergic regulation of epithelial ion transport in the mammalian intestine. Br J Pharmacol. 2006a;149:463–479. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota CL, McKay DM. M3 muscarinic receptor-deficient mice retain bethanechol-mediated intestinal ion transport and are more sensitive to colitis. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006b;84:1153–1161. doi: 10.1139/y06-068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hootman SR, Brown ME, Williams JA, Logsdon CD. Regulation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in cultured guinea pig pancreatic acini. Am J Physiol. 1986;251:G75–G83. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1986.251.1.G75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hootman SR, Verme TB, Habara Y. Effects of cycloheximide and tunicamycin on cell surface expression of pancreatic muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. FEBS Lett. 1990;274:35–38. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81323-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter DD, Nathanson NM. Decreased physiological sensitivity mediated by newly synthesized muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in the embryonic chick heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:3582–3586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.11.3582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter DD, Nathanson NM. Biochemical and physical analyses of newly synthesized muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in cultured embryonic chicken cardiac cells. J Neurosci. 1986;6:3739–3748. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-12-03739.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegaya T, Nathanson NM. Diminished functional activity of newly synthesized muscarinic receptors in stably transfected Y1 adrenal cells. J Neurochem. 1993;60:1143–1146. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iverson HA, Fix D, Nadler LS, Klevit RE, Nathanson NM. Identification and structural determination of the M3 basolateral sorting signal. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24568–24575. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501264200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob R, Preuss U, Panzer P, Alfalah M, Quack S, Roth MG, et al. Hierarchy of sorting signals in chimeras of intestinal lactase-phlorizin hydrolase and the influenza virus hemagglutinin. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8061–8067. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.8061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz A, Wu D, Simon MI. Subunits βγof heterotrimeric G protein activate b2 isoform of phospholipase C. Nature. 1992;360:686–689. doi: 10.1038/360686a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keely SJ, Barrett KE. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibits calcium-dependent chloride secretion in T84 colonic epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;284:C339–C348. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00144.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keely SJ, Calandrella SO, Barrett KE. Carbachol-stimulated transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptor and mitogen-activated protein kinase in T(84) cells is mediated by intracellular ca(2+), PYK-2, and p60(src) J Biol Chem. 2000;75:12619–12625. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.17.12619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein WL, Nathanson N, Nirenberg M. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor regulation by accelerated rate of receptor loss. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1979;90:506–512. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(79)91264-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knollman PE, Janovick JA, Brothers SP, Conn PM. Parallel regulation of membrane trafficking and dominant-negative effects by misrouted gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor mutants. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24506–24514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501978200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig JA, Edwardson JM. Kinetic analysis of the trafficking of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors between the plasma membrane and intracellular compartments. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17174–17182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig JA, Edwardson JM. Intracellular trafficking of the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor: importance of subtype and cell type. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;49:351–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivisto UM, Hubbard AL, Mellman I. A novel cellular phenotype for familial hypercholesterolemia due to a defect in polarized targeting of LDL receptor. Cell. 2001;105:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00371-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp R, Lambrecht G, Mutschler E, Moser U, Tacke R, Pfeiffer A. Human HT-29 colon carcinoma cells contain muscarinic M3 receptors coupled to phosphoinositide metabolism. Eur J Pharmacol. 1989;172:397–405. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(89)90021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusano K, Miledi R, Stinnakre J. Cholinergic and catecholaminergic receptors in the Xenopus oocyte membrane. J Physiol. 1982;328:143–170. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laduron P. Axoplasmic transport of muscarinic receptors. Nature. 1980;286:287–288. doi: 10.1038/286287a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laduron PM. Axonal transport of muscarinic receptors in vesicles containing noradrenaline and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase. FEBS Lett. 1984;165:128–132. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)80028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz W, Petrusch C, Jakobs KH, van Koppen CJ. Agonist-induced down-regulation of the m4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor occurs without changes in receptor mRNA steady-state levels. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1994;350:507–513. doi: 10.1007/BF00173020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levey AI, Kitt CA, Simonds WF, Price DL, Brann MR. Identification and localization of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor proteins in brain with subtype-specific antibodies. J Neurosci. 1991;11:3218–3226. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03218.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Luo X, Muallem S. Functional mapping of Ca2+ signaling complexes in plasma membrane microdomains of polarized cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27837–27840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400184200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liles WC, Nathanson NM. Regulation of neuronal muscarinic receptor number by protein glycosylation. J Neurochem. 1986;46:89–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1986.tb12929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H, Lindeman RP, Chase HS. Participation of protein kinase C in desensitization to bradykinin and to carbachol in MDCK cells. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:F499–F506. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.262.3.F499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madziva MT, Birnbaumer M. A role for ADP-ribosylation factor 6 in the processing of G-protein-coupled receptors. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:12178–12186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601357200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinissen MJ, Gutkind JS. G-protein-coupled receptors and signaling networks: emerging paradigms. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:368–376. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01678-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino MJ, Rouse ST, Levey AI, Potter LT, Conn PJ. Activation of the genetically defined m1 muscarinic receptor potentiates N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor currents in hippocampal pyramidal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11465–11470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui M, Yamada S, Oki T, Manabe T, Taketo MM, et al. Functional analysis of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors using knockout mice. Life Sci. 2004;75:2971–2781. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]