Abstract

Trioxaquines are antimalarial agents based on hybrid structures with a dual mode of action. One of these molecules, PA1103/SAR116242, is highly active in vitro on several sensitive and resistant strains of Plasmodium falciparum at nanomolar concentrations (e.g., IC50 value = 10 nM with FcM29, a chloroquine-resistant strain) and also on multidrug-resistant strains obtained from fresh patient isolates in Gabon. This molecule is very efficient by oral route with a complete cure of mice infected with chloroquine-sensitive or chloroquine-resistant strains of Plasmodia at 26–32 mg/kg. This compound is also highly effective in humanized mice infected with P. falciparum. Combined with a good drug profile (preliminary absorption, metabolism, and safety parameters), these data were favorable for the selection of this particular trioxaquine for development as drug candidate among 120 other active hybrid molecules.

Keywords: curative drug, malaria, Plasmodium, heme, alkglation

Malaria is 1 of the 3 major infectious diseases along with tuberculosis and AIDS (1). After World War II, the successful use of chloroquine as an efficient antimalarial drug on the 4 strains of human Plasmodia (vivax, malariae, ovale, and falciparum) and the cheap DDT insecticide significantly reduced the importance of this tropical disease up to 1960. Unfortunately, the emergence of parasite strains resistant to chloroquine and other classical drugs was at the origin of the comeback of malaria (>200 million people are infected each year and there are >1 million deaths) (2).

Fortunately, antimalarial drug research is active again after a decline period of several decades (3). The renewal of activity in this field is caused mainly by the design of new small molecules active against chloroquine-resistant (CQR) strains of Plasmodium falciparum. With a chemical structure significantly different from that of quinoline-based drugs, the natural product artemisinin and its derivatives have attracted the attention of many different groups regarding the mechanism of action of these potent antimalarials devoid of significant clinical resistance up to now (4–9). Artemisinin, with its 1,2,4-trioxane as active motif, has served as a source of inspiration for the design of synthetic peroxide-containing drugs (10–14). Based on our studies that evidenced the capacity of artemisinin derivatives and antimalarial trioxanes to alkylate free heme (ref. 5 and references therein), we designed original hybrid molecules, named trioxaquines, containing 2 pharmacophores (a 1,2,4-trioxane and a 4-aminoquinoline) to create molecules with a dual mode of action (heme alkylation with the trioxane entity, heme stacking with the aminoquinoline moiety and inhibition of hemozoin formation) (15–21). One trioxaquine prototype DU1302 shows very good activity in vitro and in vivo (mice model) but has too many centers of chirality to be considered for development (16, 18–21). Here, we report the preparation and the pharmacological properties and the antimalarial activities of PA1103/SAR116242 that we selected for full preclinical development as a drug candidate that is active by the oral route.

Results and Discussion

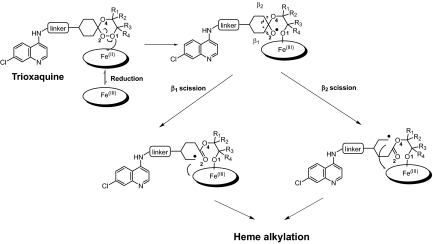

From 2003 to 2006, 120 trioxaquines and trioxolaquines (the latter hybrid molecules contain a trioxolane motif, namely an ozonide, instead of a trioxane entity) have been prepared and evaluated in vitro on chloroquine-sensitive (CSR) strains or CQR strains of P. falciparum (IC50 values ranged from 5 to 74 nM; IC50 = concentration able to reduce by 50% the incorporation of labeled hypoxanthine within the parasite at to + 48 h; see ref. 22 for details). Most of these hybrid molecules were active in vitro because of their mechanism-based design. These molecules contain a cyclohexyl entity connected to the trioxane or trioxolane entity by a spiro carbon atom to favor the generation of an alkyling C-centered radical entity. When the trioxaquines are activated by reduced heme, the homolysis of the O1 O2 bond mainly produces the formation of the alkoxy radical at O2 followed by a β-scission to generate 2 different alkylating C-centered radicals depending on the orientation of the scission (Fig. 1 and see ref. 17). To facilitate the approach of the iron metal ion onto the O1 atom, bulky substituents on that side of the trioxane should be avoided (23). All together, these data obtained from mechanistic studies facilitated the preparation of active trioxaquines (and trioxolaquines).

O2 bond mainly produces the formation of the alkoxy radical at O2 followed by a β-scission to generate 2 different alkylating C-centered radicals depending on the orientation of the scission (Fig. 1 and see ref. 17). To facilitate the approach of the iron metal ion onto the O1 atom, bulky substituents on that side of the trioxane should be avoided (23). All together, these data obtained from mechanistic studies facilitated the preparation of active trioxaquines (and trioxolaquines).

Fig. 1.

Generation of C-centered alkylated radicals by heme-mediated reductive activation of trioxaquines.

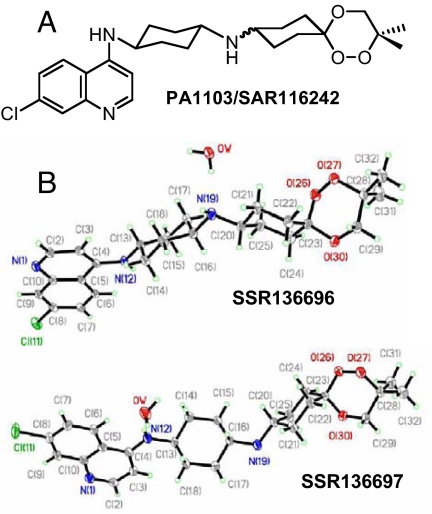

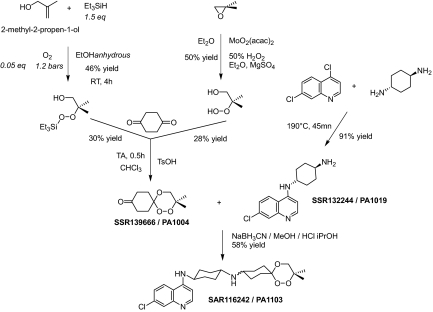

Among these 120 molecules, 72 were selected for evaluation on mice infected by the usual CSR strain of Plasmodium vinckei petteri (P. v. petteri) by using Peter and Robinson's method (24). All of these hybrid molecules were evaluated in vivo by oral route because it is the preferred mode of administration of antimalarial drugs in tropical countries. Twenty-five of the 72 molecules were considered for additional in vitro absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicology evaluation. At this stage, we decided to focus our attention only on trioxaquines and to stop the evaluation of trioxolaquines (1,2,4-trioxane motifs were preferred to trioxolanes for metabolic stability reasons). Finally, PA1103/SAR116242 was selected as a drug candidate for development in January 2007 (see Fig. 2A for formula). Both diastereoisomers (SSR136696 and SSR136697) were separated by high-pressure chromatography with a chiral column, and both structures were determined by X-ray diffraction (Fig. 2B). The trioxane moiety of PA1103/SAR116242 was made as simple as possible with a symmetry plane to limit the number of chiral centers. In addition, the presence of a second cyclohexyl ring within the linker enhanced the metabolic stability of this molecule compared with other trioxaquines with a linear aliphatic tether. The synthesis of PA1103/SAR116242 is outlined in Fig. 3. The key keto-trioxane intermediate (PA1004) was prepared by 2 different routes involving the condensation of 1,4-cyclohexanedione with 2 different peroxides (one being obtained by a Mukaiyama's peroxysilylation of an allylic alcohol and the second one by opening of an epoxide by hydrogen peroxide; see ref. 25). PA1103/SAR116242 is a reproducible 50/50 mixture of 2 diastereoisomers, because the final step is a reductive amination of the keto-trioxane with an amino-aminoquinoline (PA1019). Physicochemical parameters [log P, crystalline phase analysis, fasted state simulated intestinal fluid (FaSSIF), and fed state simulated intestinal fluid (FeSSIF) solubility, stability in acid medium], and the respect of Lipinski et al.'s rule (26) for PA1103/SAR116242 were indicative of a favorable profile for the oral bioavailability of this compound.

Fig. 2.

Structural data. (A) Formula of the trioxaquine PA1103/SAR116242. (B) X-ray structures of both stereoisomers of PA1103/SAR116242 (identified as SSR136696 and SSR136697).

Fig. 3.

Synthesis of PA1103/SAR116242.

Based on our previous studies (17–21), the dual mode of action of PA1103/SAR116242 has also been shown (heme alkylation via the reductive activation the trioxane entity, heme stacking with the aminoquinoline moiety, and inhibition of hemozoin formation). The alkylating capacity of PA1103/SAR116242 toward iron(II)-heme was evaluated in vitro, and several heme drug adducts have been observed (m/z peaks at 917, 858, and 818). Preliminary data indicates that heme-PA1103 adducts are also generated in infected mice as previously observed in vivo with the trioxaquine prototype DU1301 (21). However, inhibition of heme aggregation by PA1103/SAR116242 was confirmed by monitoring the characteristic bands of β-hematin in infrared spectroscopy at 1,660 and 1,210 cm−1 (see ref. 20 for experimental details). These experiments confirmed the expected dual mode of action of this selected trioxaquine when compared with the behavior of chloroquine and artemisinin in the same experimental conditions.

The in vitro and in vivo antiplasmodial activities of PA1103 are presented in Tables 1–3. Because both diastereoisomers of PA1103/SAR116242 have the same in vitro activities (data not shown), all reported data were obtained with the 50/50 mixture of stereoisomers. Seven different laboratory strains of P. falciparum issued from different geographical regions were used for the in vitro evaluation of trioxaquine activities (Table 1). PA1103/SAR116242 has a similar activity on CQS and CQR strains of P. falciparum (with IC50 values ranging from 7 to 24 nM). Moreover, the activity of PA1103 is within the same range of activity of artemisinin. Moreover the in vitro parasite time-killing activity of PA1103/SAR116242 was investigated with a CQR strain (FcB1). Both PA1103/SAR116242 and artesunate were able to generate 100% of parasitemia reduction 72 h after the treatment of the parasite at t0 with 1 dose of drug at 100 ng/mL. On the same strain with a higher dose (1 μg/mL) of chloroquine or mefloquine, we observed only 97% and 93% reduction of the parasitemia after 72 h.

Table 1.

IC50 values in nM for PA1103/SAR116242 and standard drugs against P. falciparum

| Compound |

P. falciparum strains |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FcB1(CQR),Colombia | FcR3(CQR),Gambia | Palo Alto(CQR),Ouganda | W2(CQR)+,Indo-China | FcM29(CQR)+,Cameroon | D6(CQS),Sierra Leone | F32(CQS),Tanzania | |

| PA1103/SAR116242 | 24 ± 3 | 12 ± 3 | 15 ± 3 | 15 ± 3 | 10 ± 3 | 7 ± 6 | 13 |

| Chloroquine | 147 ± 3 | 114 ± 3 | 126 ± 3 | 236 ± 3 | 518 ± 5 | 11 ± 3 | 25 ± 3 |

| Artemisinin | 10 ± 4 | 8 ± 5 | 10 ± 5 | 10 ± 5 | 7 ± 5 | 8 ± 5 | 9 ± 5 |

Table 2.

Growth inhibition (+95% CI) in nM of freshly isolated P. falciparum field isolates from Lambaréné, Gabon (the data window is indicated in parentheses)

| Compound | IC50 (95% CI) | IC90 (95% CI) | IC99 (95% CI) | MIC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA1103/SAR116242 | 19.8 (14.0–28.1) | 29.3 (19.3–44.4) | 44.8 (26.8–74.6) | 47.2 (33.4–66.7) |

| Chloroquine | 196 (142–270) | 301 (228–396) | 531 (375–754) | |

| Artesunate | 2.34 (1.32–4.18) | 6.46 (3.17–13.2) | 19.5 (7.95–48.0) |

IC was determined by HRP2 ELISA (28). PA1103/SAR116242: n = 18. Chloroquine: n = 17. Artesunate: n = 12. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined by Mark III in vitro microtest; n = 36.

To document the variability of the efficacy of PA1103/SAR116242 against parasites having diverse genetic backgrounds (an obvious limitation of laboratory strains), a study has been conducted with fresh patient isolates in the Albert Schweitzer Hospital in Lambaréné, Gabon (Table 2), an area of high-grade chloroquine resistance (27). It should be noted that the IC99 value for PA1103/SAR116242 is only 2.2 times its IC50 value, whereas the same ratio for artesunate is 8.3. This is an indication of a very good response of the activity of the drug candidate as a function of the concentration (Table 2).

In vivo data (Table 3) were obtained on mice infected with 2 different rodent strains in the 4-day suppressive test: P. v. petteri (CQS strain) and P. vinckei vinckei (CQR strain). Both strains allowed us to obtain a direct comparison between in vitro data on P. falciparum and in vivo data generated with rodent models. With mice infected with the CQS strain (P. v. petteri), we first evaluated the pharmacodynamic properties of PA1103/SAR116242 with 2 different modes of administration, namely oral and i.p. routes (oral route assays were performed by using a suspension in methyl-cellulose/tween). Using these 2 modes of administration, the CD100 values were similar and ranged from 26 to 32 mg/kg per day (the CD100 value is the drug quantity in mg/kg per day that cured 100% of infected mice on day 30), confirming a good oral bioavailability of this drug candidate. Both diastereoisomers, SSR136696 and SSR136697, were found to be equally potent by oral route on mice infected with P. v. petteri (CD100 = 32 mg/kg per d). In addition, when using the CQ-resistant strain (P. v. vinckei), we found that the activity of PA1103/SAR116242 was practically the same as that obtained with the CQS strain (P. v. petteri). The complete cure of infected mice, by oral route, was obtained in both cases at doses ≈30 mg/kg per day (Table 3). This result correlates with the in vitro efficiency data obtained with that compound on CQS and CQR strains. Compared with artesunate, a widely used artemisinin derivative, PA1103/SAR116242 was more efficient in the CQR rodent model (CD100 value = 30 compared with 100 mg/kg per day for artesunate).

Table 3.

In vivo antimalarial activity of PA1103/SAR116242 against P. v. vinckei (CQR strains) and P. v. petteri (CQS strain) in swiss mice by oral route

| Compound |

P. vinckei strains |

|

|---|---|---|

| P. v. vinckei CQR CD100 (mg/kg per day) | P. v. petteri CQS CD100 (mg/kg per day) | |

| PA1103/SAR116242 | 30 | 32 |

| Chloroquine | >100 | 16 |

| Artesunate | 100 | 32 |

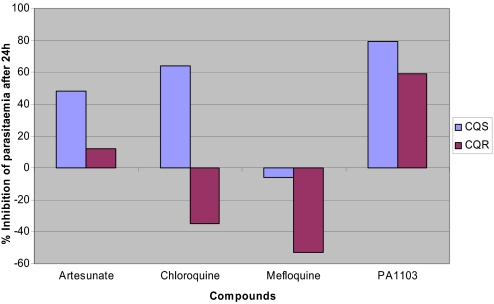

A recrudescence-type experiment was also designed to evaluate the capacity of PA1103/SAR116242 to quickly reduce the parasitemia in the rodent model. PA1103/SAR116242 was administered at a fixed dose of 25 mg/kg per day. The other drugs used as comparators (artesunate, chloroquine, and mefloquine) were evaluated at the same molar concentration as that used for PA1103/SAR116242 to obtain a direct comparison of their efficacy. After 1 dose by oral route of these different antimalarial compounds given to mice infected with CQS and CQR strains with a parasitemia level ≈40%, PA1103/SAR116242 was the most potent molecule to reduce the parasitemia after 24 h (Fig. 4; a negative inhibition means that the parasitemia was growing). Chloroquine and mefloquine were unable to reduce the growth of the CQR strain, and PA1103 was more efficient than artesunate on both strains.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of compound effect on parasitemia in vivo after 24 h of 1 dose of 25 mg/kg per day for PA1103/SAR116242 per oral route in both CQS (P. vinckei petteri) and CQR (P. vinckei vinckei) rodent strains.

In addition, we decided to investigate the activity of this particular trioxaquine in humanized mice infected with the human parasite P. falciparum. A curative-type experiment was designed to evaluate the activity of PA1103/SAR116242 in mice infected with the CQS strain 3D7 and the CQR strain W2. A 4-day treatment with 32 or 63 mg/kg per day of PA1103/SAR116242 per oral route induced a significant or complete reduction of parasitemia in all treated mice (Table 4). Its activity at the dose of 63 mg/kg per day was similar to that observed in mice treated with 54 mg/kg per day of artesunate at D4, and 24 h later all trioxaquine-treated mice had cleared the infection. As observed in in vitro studies, activity of this compound was independent of the chloroquine strain sensitivity. These results confirm the activity of this candidate drug in a human Plasmodia mouse model that allows a more reliable evaluation of the PA1103/SAR116242 activity against the real parasite target.

Table 4.

In vivo activity of PA1103/SAR116242 against the erythrocytic forms of P. falciparum in humanized mice

| Compound | Dose, mg/kg per day | P. falciparum strain | Parasitemia reduction at D4, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chloroquine | 15 | 3D7 | 100 (n = 3) |

| 15 | W2 | 0 (n = 5) | |

| 43 | 3D7 | 100 (n = 5) | |

| 43 | W2 | 15 (n = 5) | |

| Artesunate | 4 | 3D7 | 28 (n = 3) |

| 4 | W2 | 89 (n = 4) | |

| 54 | 3D7 | ND | |

| 54 | W2 | 100 (n = 4) | |

| PA1103/SAR116242 | 32 | 3D7 | ND |

| 32 | W2 | 77 (n = 4) | |

| 63 | 3D7 | 100 (n = 4) | |

| 63 | W2 | 96 (n = 5) |

3D7: in vitro CQS strain; W2: in vitro CQR strain. n = number of mice per group. ND = nondetermined value.

Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicology in vitro data were obtained on PA1103/SAR116242. In vitro drug metabolism studies performed with human liver microsomes indicated a low metabolism rate (11% of biotransformation within 20 min at 37 °C) compared with the fast and complete (100%) metabolization of artesunate and 29% for chloroquine in the same experimental conditions.

In human hepatocytes, PA1103/SAR116242 was metabolized at an intermediary-high clearance (0.11 ± 0.05 mL × h−1 × 10−6 hepatocytes) with moderate intersubject variability. In the same experiment, artesunate was more rapidly metabolized (0.61 ± 0.22 mL × h−1 × 10−6 hepatocytes).

In addition, in vitro inhibitions of the major human cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoforms and CYP isoform induction studies conducted in human hepatocytes indicated unlikely drug metabolism-based drug–drug interactions (data not shown). Moreover, no mechanism-based inhibition of the major human CYP isoforms was observed in human liver microsomal fraction for PA1103/SAR116242.

A preliminary in vitro study on the membrane permeability of PA1103/SAR116242 on the intestinal epithelial model (Caco-2/TC-7 cell monolayer) indicated that this trioxaquine possessed nearly the same transepithelial permeability as chloroquine (Ptot between 10 and 20 × 10−7 cm/s). These data bring additional evidence in favor of an efficient oral absorption of this drug candidate. Preliminary pharmacokinetics data on rat confirmed a good biodisponibility of this drug candidate (data not shown).

During the experiments with infected mice, no particular toxic effects were detectable during the 4-day suppressive test when using up to 4 × 100 mg/kg per day by oral administration. The same absence of toxic effects was observed when treating healthy mice by a single oral dose of 300 mg/kg per day (18). The absence of any drug-related adverse effects (anorexia, weight loss, diarrhea, and behavioral alterations) 30 days after drug administration is an indication of a potentially large therapeutic window for trioxaquines.

Concerning potential toxicological profile of this trioxaquine, assays such as the mini-Ames test, Foetax, and the in vitro micronucleus assay were used for identifying possible mutagenic or teratogenic effects. In all cases, PA1103/SAR116242 did not show any mutagenic or clastogenic activity. The cardiac toxicity (QT interval prolongation) was also evaluated by the conventional whole-cell patch-clamp technique by recording outward potassium currents [human Ether-a-Go-go related gene (hERG)] from single cells of HEK-293. PA1103/SAR116242 inhibited this K+ channel with an IC50 value of 1.5 μM, which was in the same range as chloroquine (hERG IC50 = 3 μM). In conscious rats, this trioxaquine did not induce any effect on blood pressure, heart rate, or QT and QTc intervals up to 100 mg/kg orally.

In addition, the 2 separated diastereoisomers of PA1103/SAR116242 were found equipotent in antimalarial in vitro and in vivo assays and also displayed a fully similar profile in preliminary absorption, metabolism, and safety assays.

The goal of this research was to identify the best hybrid trioxaquine molecule combining the qualities of artemisinin and chloroquine. The high in vivo antimalarial activity of PA1103/SAR116242 against sensitive and resistant P. falciparum strains, together with a dual mode of action (artemisinin-like and chloroquine-like), good bioavailability, and low toxicity make this molecule a promising candidate for a covalent bitherapy strategy. For these different reasons the trioxaquine PA1103/SAR116242 was selected at the beginning of 2007 for regulatory drug development.

Methods

Synthesis of PA1103/SAR116242.

As described (25), the typical procedure to synthesize PA1103/SAR116242 was accomplished by a 4-step synthesis coming from 2 different ways for building the 1,2,4-trioxane part of the molecule. When not specified, all data were obtained with the 50/50 mixture of both diastereoisomers.

Crystallographic Data.

3D structures presented in Fig. 4 were collected at low temperature by using an oil-coated shock-cooled crystal with a Bruker-AXS CCD 1000 diffractometer with MoKα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). The structures were solved by direct methods, and all nonhydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically by using the least-squares method on F2. Experimental data, distances, and angles for the 2 structures are presented in supporting information (SI) Tables S1 and S2.

Evidence for the Formation of Heme-Trioxaquine Adducts.

Heme-PA1103/SAR116242 adducts were isolated by using a modified procedure of that described in ref. 6. Hemin was reacted with PA1103/SAR116242 in the presence of sodium dithionite in DMSO for 1 h at room temperature ([hemin] = 20 mM, hemin/PA1103/SAR116242/S2O42− molar ratios = 1/1.1/9.4). The reaction mixture was then purified by column chromatography (silica gel, methanol/pyridine, 99/1, vol/vol). The LC-MS analysis of the first isolated fraction indicated the presence of heme-trioxaquine adducts.

In Vitro Antimalarial Activity.

The antiplasmodial activity of PA1103/SAR116242 was evaluated by using the classical radioactive microdilution method described by Desjardins et al. (22) with various P. falciparum strains initially provided by Centre Hospitalier Universitaire-Rangueil (Toulouse, France) and the Institut de Médecine Tropicale du Service de Santé des Armées-PHARO (Marseille, France). Concentrations of PA1103/SAR116242 that inhibited 50% of the parasite growth (IC50 values) were graphically determined by plotting the drug concentration versus percentage of parasite growth inhibition at 48 h of incubation.

Freshly isolated parasites from patients in Lambaréné were cultivated immediately after blood sampling and analyzed after 26 h (Mark III) or 72 h [histidine-rich protein 2 (HRP2) ELISA]. Parasite cultivation and growth detection were done as described (ref. 28 and www.who.int/drugresistance/malaria/en/markiii.pdf), except that 0.5% Albumax replaced human serum in the parasite growth medium. Inhibitory concentrations were determined from 4-parameter curve fits of the logarithm of drug concentration versus HRP2 concentration in the parasite lysate. Minimal inhibitory concentration was defined as the first concentration where no schizont maturation was detected in Mark III in vitro micro test and as the IC99 value in HRP2 ELISAs.

In Vivo Antimalarial Efficacy Studies.

In vivo antimalarial activity of PA1103/SAR116242 was determined against the rodent strains P. v. petteri (CQS) and P. v. vinckei (CQR) according to the 4-day suppressive test (24). Swiss mice were inoculated i.p. with 2 × 106 parasitized red blood cells (CQS strain) or 1 × 106 parasitized red blood cells (CQR strain). Thereafter, PA1103/SAR116242 was then given a fixed dose once daily for 4 consecutive days beginning on the day of infection. Parasitemia levels were determined on the day after the last treatment and mice cured on day 30 were recorded.

Experiments on the onset of drug action in vivo have been conducted on infected animals (5 mice per compound tested) with the CQS and CQR strains. When animals presented a parasitemia level between 20% and 40% (normally on day 4 after infection), a fixed single dose of the drug was administrated to these animals and parasitemia was monitored 24 h later by GIEMSA thin blood smear. Mean value of parasitemia for each group of mice was calculated and the percentage of reduction of the parasitemia was determined.

P. falciparum infection in humanized mice was obtained as described (29). Mice bearing parasitemias >0.1% were selected to evaluate the activity of PA1103/SAR116242, chloroquine, and artesunate in this model. Antimalarial treatments consisted of a once-daily oral dose administered for 4 days. Parasitemias were monitored by GIEMSA-stained thin blood smears. Mean values and SD of parasitemias were calculated for each group of mice. Twenty-four hours after the end of the treatment, antimalarial activity of the different treatments was determined as the percentage of parasitemia reduction in treated mice when compared with parasitemia in nontreated mice.

In Vitro Permeability.

Transepithelial transport of PA1103/SAR116242 was evaluated by using in vitro Caco-2/TC-7 cell monolayers (30). The permeability of the compound at the concentration of 20 μM was performed by using an apical compartment containing HBSS at pH 6.5 with 0.5% (wt/vol) BSA and a basal compartment with HBSS at pH 7.4 with 5% (wt/vol) BSA. Incubations were conducted at 37 °C for 4 h in the “apical–basal” direction, and samples were analyzed by using LC-MS/MS method.

The velocity of blood–brain barrier (BBB) crossing was investigated by using the in vitro model of the bovine brain microvascular endothelial cell monolayer (31). For comparison, the permeability value of an internal reference compound that rapidly crosses the BBB in vivo was measured in parallel for each experiment.

In Vitro Metabolism.

Evaluation of the metabolic stability of PA1103/SAR116242 was carried out by using hepatic microsomal fractions prepared from mouse, rat, and human at a substrate concentration of 5 μM and a microsomal protein concentration of 1 mg/mL. Incubations were conducted at 37 °C for 20 min in the presence of BSA at a concentration of 1 mg/mL and CYP and flavin-containing monooxygenase cofactor (NADPH, 1 mM). After 20 min of incubation, the remaining concentration of PA1103/SAR116242 was measured by LC-MS/MS.

In Vitro Evaluation Effect on hERG Current.

The effect of PA1103/SAR116242 on hERG current was investigated in vitro by using an automated parallel patch-clamp system in the whole-cell configuration on HEK293 cells stably transfected with the human gene of ERG (32).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Anne Robert (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique-Laboratoire de Chimie de Coordination), Françoise Benoit-Vical (Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale Fellow, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique-Laboratoire de Chimie de Coordination and Centre Hospitalier Universitaire-Toulouse), Jérôme Cazelles (Palumed), and Jean-François Magnaval (Centre Hospitalier Universitaire-Toulouse) for discussions; Daniel Parzy and Bruno Pradines (Institut de Medicine Tropicale du Pharo-Marseille-Pharo, Marseille) for different strains of parasites; Daniel Dives (Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale-Pasteur, Lille) for the murine CQR strain; Céline Berrone, Carine Duboé, Angélique Erraud, Katia Jonot, and Christine Salle for technical assistance; Philippe Ochsenbein (Sanofi-Aventis) for X-ray analyses; Christophe Loup (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique-Laboratoire de Chimie de Coordination) for performing the infrared study on heme polymerization; and all participants and the study team of the Medical Research Unit of the Albert Schweitzer Hospital in Lambaréné, in particular Saadou Issifou, Michael Ramharter, Florian Kurth, and Peter Pongratz. This work was supported by Palumed, Sanofi-Aventis, and Agence Nationale Pour la Recherche Grant ANR 06-RIB-020-03. Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire-Toulouse, and the Région Midi-Pyrénées provided partial logistic and/or financial support.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Crystallographic Cambridge Data Centre, www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk [accession nos. CCDC700855 (SSR136696) and CCDC700856 (SSR136697).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0804338105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Greenwood BM, Bojang K, Whitty CJ, Targett GA. Malaria. Lancet. 2005;365:1487–1498. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66420-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White NJ, et al. Averting a malaria disaster. Lancet. 1999;353:1965–1967. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07367-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nwaka S, Ridley RG. Virtual drug discovery and development for neglected diseases through public-private partnerships. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:919–928. doi: 10.1038/nrd1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meshnick SR, Traylor TE, Kamchonwongpaisan S. Artemisinin and the antimalarial endoperoxides: From herbal remedy to targeted chemotherapy. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:301–315. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.2.301-315.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robert A, Cazelles J, Dechy-Cabaret O, Meunier B. From mechanistic studies on artemisinin derivatives to new modular antimalarial drugs. Acc Chem Res. 2002;35:167–174. doi: 10.1021/ar990164o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robert A, Benoit-Vical F, Claparols C, Meunier B. The antimalarial drug artemisinin alkylates heme in infected mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13676–13680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500972102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olliaro PL, Haynes RK, Meunier B, Yuthavong Y , Possible modes of action of the artemisinin-type compounds. Trends Parasitol. 2001;17:122–126. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(00)01838-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu Y. How might Qinghaosu (artemisinin) and related compounds kill the intraerythrocytic malaria parasite? A chemist's view. Acc Chem Res. 2002;35:255–259. doi: 10.1021/ar000080b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eckstein-Ludwig U, et al. Artemisinins target the SERCA of Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2003;424:957–962. doi: 10.1038/nature01813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jefford CW. New development in synthetic drugs as artemisinin mimics. Drug Discov Today. 2007;12:487–495. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Posner GH, et al. Malaria-infected mice are cured by oral administration of new artemisin derivatives. J Med Chem. 2008;51:1035–1042. doi: 10.1021/jm701168h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Neill PM, Posner GH. A medicinal chemistry perspective on artemisinin and related endoperoxides. J Med Chem. 2004;47:2945–2964. doi: 10.1021/jm030571c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vennerstrom JL, et al. Identification of an antimalarial synthetic trioxolane drug development candidate. Nature. 2004;430:900–904. doi: 10.1038/nature02779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh C, Malik H, Puri SK , Orally active 1,2,4-trioxanes: Synthesis and antimalarial assessment of a new series of 9-functionalized 3-(1-arylvinyl)-1,2,5-trioxaspiro[5.5]undecanes against multi-drug-resistant Plasmodium yoelii nigerensis in mice. J Med Chem. 2006;49:2794–2803. doi: 10.1021/jm051130r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dechy-Cabaret O, Benoit-Vical F, Robert A, Meunier B. Preparation and antimalarial activities of “trioxaquines,” new modular molecules with a trioxane skeleton linked to a 4-aminoquinoline. ChemBioChem. 2000;1:281–283. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20001117)1:4<281::AID-CBIC281>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dechy-Cabaret O, et al. Synthesis and antimalarial activity of trioxaquine derivatives. Chem Eur J. 2004;10:1625–1636. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laurent SAL, Loup C, Mourgues S, Robert A, Meunier B. Heme alkylation by the antimalarial endoperoxides artesunate and trioxaquine. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:653–658. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benoit-Vical F, et al. Trioxaquines: New antimalarial agents active on all erythrocytic forms including gametocytes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:1463–1472. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00967-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meunier B. Hybrid molecules with a dual mode of action: Dream or reality? Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:69–79. doi: 10.1021/ar7000843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loup C, Lelièvre J, Benoit-Vical F, Meunier B. Trioxaquines and heme-artemisinin adducts inhibit the in vitro formation of hemozoin better than chloroquine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3768–3770. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00239-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bousejra-El Garah F, Claparols C, Benoit-Vical F, Meunier B, Robert A. The antimalarial trioxaquine DU1301 alkylates heme in malaria-infected mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2966–2969. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00165-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desjardins RE, Canfield CJ, Haynes JD, Chulay JD. Quantitative assessment of antimalarial activity in vitro by a semiautomated microdilution technique. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979;16:710–718. doi: 10.1128/aac.16.6.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cazelles J, Robert A, Meunier B. Alkylating capacity and reaction products of antimalarial trioxanes after activation by a heme model. J Org Chem. 2002;67:609–619. doi: 10.1021/jo010688d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peters W, Robinson BL. In: Handbook of Animal Models of Infection. Zak O, Sande ME, editors. New York: Academic; 1999. pp. 757–773. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coslédan F, Pellet A, Meunier B. French Patent application FR06/05235. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1997;23:3–25. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borrmann S, et al. Reassessment of the resistance of Plasmodium falciparum to chloroquine in Gabon: Implications for the validity of tests in vitro vs. in vivo. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2002;96:660–663. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(02)90345-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noedl H, et al. Simple histidine-rich protein 2 double-site sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the use in malaria drug sensitivity testing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:3575–3577. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.8.3575-3577.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moreno A, et al. The course of infections and pathology in immunomodulated NOD/LtSz-SCID mice inoculated with Plasmodium falciparum laboratory lines and clinical isolates. Int J Parasitol. 2006;36:361–369. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grès MC, et al. Correlation between oral drug absorption in humans, and apparent drug permeability in TC-7 cells, a human epithelial intestinal cell line: Comparison with the parental Caco-2 cell line. Pharm Res. 1998;15:726–733. doi: 10.1023/a:1011919003030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lundquist S, et al. Prediction of drug transport throught the blood-brain barrier in vivo: A comparison between two in vitro cell models. Pharm Res. 2002;19:976–981. doi: 10.1023/a:1016462205267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanguinetti MC, Tristani-Firouzi M. hERG potassium channels and cardiac arrythmia. Nature. 2006;440:463–469. doi: 10.1038/nature04710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.