Abstract

Heart valve function is achieved by organization of matrix components including collagens, yet the distribution of collagens in valvular structures is not well defined. Therefore, we examined the temporal and spatial expression of select fibril-, network-, beaded filament-forming, and FACIT collagens in endocardial cushions, remodeling, maturing, and adult murine atrioventricular heart valves. Of the genes examined, col1a1, col2a1, and col3a1 transcripts are most highly expressed in endocardial cushions. Expression of col1a1, col1a2, col2a1, and col3a1 remain high, along with col12a1 in remodeling valves. Maturing neonate valves predominantly express col1a1, col1a2, col3a1, col5a2, col11a1, and col12a1 within defined proximal and distal regions. In adult valves, collagen protein distribution is highly compartmentalized, with ColI and ColXII observed on the ventricular surface and ColIII and ColVa1 detected throughout the leaflets. Together, these expression data identify patterning of collagen types in developing and maintained heart valves, which likely relate to valve structure and function.

Keywords: collagen, heart, valves, extracellular matrix

INTRODUCTION

Congenital heart disease, related to defects in heart valve structure and function, affect almost 1% of live births (Rosamond et al., 2007). Efficient heart valve function is achieved by compartmentalization of specialized extracellular matrix (ECM) layers arranged according to blood flow (Rabkin-Aikawa et al., 2005). These layers of connective tissue arise from valve precursor cells of the endocardial cushions during development, and provide the mature valve with the necessary strength, flexibility, and compliance in response to changes in hemodynamic pressures during the cardiac cycle (Gross and Kugel, 1931; Lincoln et al., 2004; Person et al., 2005; Rabkin-Aikawa et al., 2005). Previous studies have shown that each matrix layer offers a unique structural integrity within distinct compartments of normal valve structures, attributed to differential contributions of several ECM components including collagens (Lincoln et al., 2006b). In contrast, diseased or malfunctioning valves lose their layer compartmentalization and show excessive deposition of disorganized matrix components and diminished structural integrity (Hinton et al., 2006). Consequently, the ability of the valve leaflets to open and close during the cardiac cycle is weakened leading to valvular insufficiency or regurgitation. Therefore, the establishment and maintenance of defined connective tissue architecture is essential for normal heart valve structure and function. Despite the clinical significance, the temporal and spatial distribution of ECM components within developing and mature valves is not well defined.

There are several function-based collagen classes including fibril-,network-, and beaded filament-forming, as well as fibril-associated collagens with interrupted triple helices (FACITs). The structural integrities of different connective tissue systems are related to the contribution and organization of each of the collagen fiber classes (Kadler et al., 2007). Fibril-forming collagens including colI, colIII, colV, and colXI, prominent in bone, skin, and tendons, provide tensile strength by forming parallel bundles of highly organized fibrils (Kadler et al., 2007), while FACITs, including colIX, colXII, and colXIV, are proteoglycans that serve to bridge and stabilize collagen fibrils (Shaw and Olsen 1991). In contrast, network-forming colIV, colVIII, and colX form lattices, including that of the basement membrane, which provide filtration, or crosslink and stabilize collagen fibrils (Stephan et al., 2004). Previous expression studies in heart valves have identified a high abundance of fibril-forming collagens including types I, II, III, V, XI (Swiderski et al., 1994; Lincoln et al., 2006a,b), as well as network- and beaded filament-forming collagen types IV and VI, respectively (Liu et al., 1997; Klewer et al., 1998; Person et al., 2005; Lincoln et al., 2006a).

In connective tissue systems, collagen distribution and organization are indispensable for normal tissue structure and function; disruptions in collagen genes are known to cause defects in several connective tissues, including skin, bone and heart valves (Malfait and De Paepe, 2005; Tinkle and Wenstrup, 2005; Grau et al., 2007). Human mutations in COL1A1, COL1A2, COL5A1, and COL11 genes can result in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), primarily associated with skin and bone abnormalities, although mitral and aortic valve dysfunction have also been reported (Malfait et al., 2006). The association of EDS with valve pathology is supported by studies in col5a1+/-;col11a1-/- mouse models of the disease that show pathological heart valve structures with increased colI and colIII deposition (Wenstrup et al., 2004; Lincoln et al., 2006b). Patients with Osteogenesis Imperfecta related to COL1 mutations, show a high prevalence of mitral valve insufficiency (Glesby and Pyeritz, 1989) and col1-/- mice die in utero with reported cardiac defects (Löhler et al., 1984). Valve dysfunction is also observed in over 50% of patients with Stickler Syndrome, a disease caused by mutations in COL11a1 and COL2A1 (Liberfarb et al., 1986). Collectively, these previous studies from both human disease and mouse models highlight the importance of collagen organization and distribution for normal heart valve structure and function. Despite the significance of collagen contribution to heart valve function, the relationships and role of differential collagens in normal heart valve structures are not yet clear.

In this study, we examine the temporal and spatial expression of select fibril-, network-, beaded filament-forming, and FACIT collagens in endocardial cushions (embryonic day (E) 12.5), remodeling (E17.5), maturing (neonate), and maintained (adult) murine atrioventricular heart valves. TaqMan Low-Density Array (TLDA) analysis identified predominantly high transcript levels of col1a1, col1a2, and col3a1 at all stages. In addition to fibril-forming collagens, transcript levels of col12a1, a FACIT collagen, are significantly increased at the remodeling and maturation stages. At the neonatal stage, we observe the greatest number of increased collagen transcript levels compared to any other time point. Collagen proteins I, III, Va2, XIa1, XII, and XIV are predominantly expressed throughout the leaflet of neonate valves, with somewhat diminished expression at the distal tip of the leaflets. By adult stages, collagen expression is highly compartmentalized within the valve structures. Collagen types I and XII are enriched within the ventricular region of the valve, colVa1 within proximal valve regions including the annulus, while colIII expression is observed throughout the valve leaflet. These data show a collective array of collagen expression during important stages of valve formation, maturation, and maintenance that are likely essential for normal heart valve structure, integrity, and function.

RESULTS

Collagen Genes Are Differentially Expressed During Atrioventricular Valve Development, Remodeling, and Maintenance

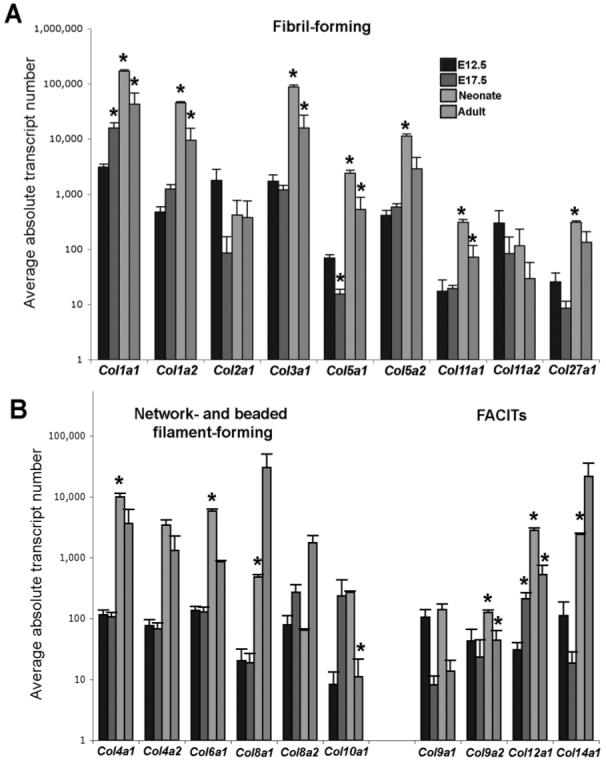

Collagens are building blocks required to maintain the structure and function of many connective tissue systems including heart valves (Lincoln et al., 2006b; Kadler et al., 2007). TLDA analysis was performed to detect quantitative changes in transcript levels of select collagen genes in atrioventricular canal regions from E12.5, E17.5, neonatal, and adult (2 months) mouse hearts. Transcript levels of fibril-forming collagens (Fig. 1A) are higher than that of network-, beaded filament-forming, and FACIT collagens (Fig. 1B) at all time points examined. At E12.5, representative of endocardial cushion stages, col1a1, col1a2, col2a1, and col3a1 have the highest transcript levels. During valve remodeling (E17.5), col1a1 remains predominant, and col12a1 transcript levels increase significantly compared to E12.5. Notably, col5a1 transcript is significantly decreased at E17.5. The transition from remodeling valves at E17.5 to maturing neonatal valves is associated with the greatest number of collagen genes with significantly increased transcript abundance. Transcript levels of col1a1, col1a2, col3a1, col5a2, col6a1, col12a1, and col14a1 are notably high at this stage. Although col1a1, col1a2, col3a1, col5a1, col5a2, col12a1, and col14a1 transcript levels remain high in adult heart valves, transcript levels of col1a1, col1a2, col3a1, col5a1, col10a1, col11a1, col9a2, and col12a1 actually decrease in the adult compared to neonatal stages. Table 1 summarizes TLDA data shown in Figure 1 and categorizes approximate transcript levels greater than 5,000 transcripts (+++), 500-4,999 transcripts (++), 50-499 transcripts (+), and fewer than 50 transcripts (empty).

Fig. 1.

TLDA analysis to determine transcript levels of select collagen genes in atrioventricular canal regions from E12.5, E17.5, neonatal, and adult mouse hearts. Average absolute transcript numbers of each chosen collagen were calculated from ΔCt values normalized to gadph levels. A: Transcript levels of fibril-forming collagens at endocardial cushion (E12.5), valve remodeling (E17.5), valve maturation (neonate), and maintained (2 months) stages. B: Transcript levels of network-, beaded filament-forming, and FACIT collagens at the same time points. Asterisks indicate significant changes in transcript levels from the previous time point for each collagen gene examined.

TABLE 1. Summary of TLDA Dataa.

| E12.5 | E17.5 | Neonatal | Adult | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fibril | ||||

| Col1a1 | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Col1a2 | + | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| Col2a1 | ++ | + | + | + |

| Col3a1 | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| Col5a1 | + | ++ | ++ | |

| Col5a2 | + | ++ | +++ | ++ |

| Col11a1 | + | + | ||

| Col11a2 | + | + | + | |

| Col27a1 | + | + | ||

| Network/Beaded | ||||

| Col4a1 | + | + | +++ | ++ |

| Col4a2 | + | + | ++ | ++ |

| Col6a1 | + | + | +++ | ++ |

| Col8a1 | + | +++ | ||

| Col8a2 | + | + | + | ++ |

| Col10a1 | + | + | ||

| FACIT | ||||

| Col9a1 | + | + | ||

| Col9a2 | + | |||

| Col12a1 | + | ++ | ++ | |

| Col14a1 | + | ++ | +++ | |

TLDA analysis was performed using samples isolated from the AV canal region at E12.5, E17.5, neonatal, and 2 months to detect quantitative changes in select collagen gene expression. Approximated absolute copy numbers of tested collagen genes are categorized as greater than 5,000 transcripts (+++), 500-4,999 transcripts (++), 50-499 transcripts (+), and fewer than 50 transcripts (empty).

Collagens I, III, and XII Are Differentially Localized in Remodeling Atrioventricular Heart Valves at E17.5

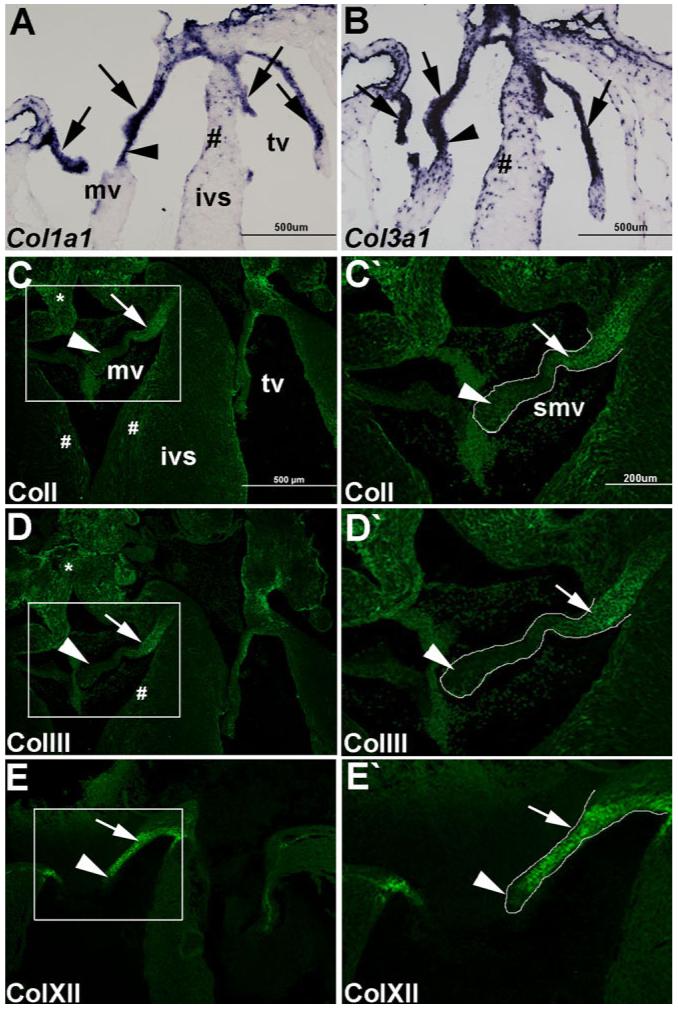

Heart valve remodeling during late stages of embryonic development is associated with changes in ECM distribution and organization (Lincoln et al., 2006b). TLDA analysis revealed apparently high transcript levels of col1a1, col1a2, and col3a1, and significantly increased col12a1 in remodeling valves at E17.5 (Fig. 1). Therefore, in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry were performed to support these findings and determine the spatial distribution of these collagens in remodeling atrioventricular valve structures (Fig. 2). At the transcript level, col1a1 (Fig. 2A) and col3a1 (Fig. 2B) expression is observed throughout the mitral and tricuspid valve leaflets (arrows, Fig. 2A,B) and chordae tendineae (arrowheads, Fig. 2A,B). Expression is also noted in the myocardium (#, Figs. 2A,B), likely associated with capillary walls and the fibrous skeleton (Lincoln et al., 2006a). At the protein level, colI and colIII are most highly expressed within proximal regions of the mitral valve leaflets (arrows, Fig. 2C,C’,D,D’), with diminished expression in distal regions (arrowheads, Fig. 2C,C’,D,D’). Additional expression was also detected in the ventricular myocardium (#, Fig. 2C,D) and great vessels (*, Fig. 2C,D). The subtle variation in collagen expression observed by in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry may be attributed to differences in transcript stability and protein turnover. Compared to colI and colIII, collagen XII is more widely expressed in valve leaflets (arrow, Fig. 2E,E’), although expression was similarly undetected at the distal tip (arrowhead, Fig. 2E,E’). These findings demonstrate the differential expression of fibril- and network-forming collagens during stages of heart valve remodeling.

Fig. 2.

Collagens I, III, and XII are differentially localized in remodeling atrioventricular heart valves at E17.5. In situ hybridization (A, B) and immunofluorescence (C-E) were used to detect spatial expression of highly expressing collagens in remodeling valves at E17.5. Col1a1 (A) and col3a1 (B) mRNA expression in atrioventricular heart valve leaflets (arrow) and chordae tendineae (arrowhead). #, indicates observed expression in the myocardium. ColI (C, C’), colIII (D, D’), and colXII (E, E’) protein expression in atrioventricular valve leaflets. Mitral valve leaflets are outlined and shown at higher magnification in C’, D’, E’. Arrows indicate high levels of colI (C, C’), colIII (D, D’), and colXII (E, E’) expression in proximal regions of the valve leaflet, while arrowheads refer to reduced expression at the distal tips. Note additional colI and colIII expression in the ventricular myocardium (#, A, B) and vessels (*, A, B). mv, mitral valve; tv, tricuspid valve; ivs, intraventricular septum; smv, septal mitral valve. Scale bar in A-E = 500 μm; in C’-E’ = 200 μm.

Fibril- and Network-Forming Collagens Are Highly Expressed in Neonate Mitral Valves

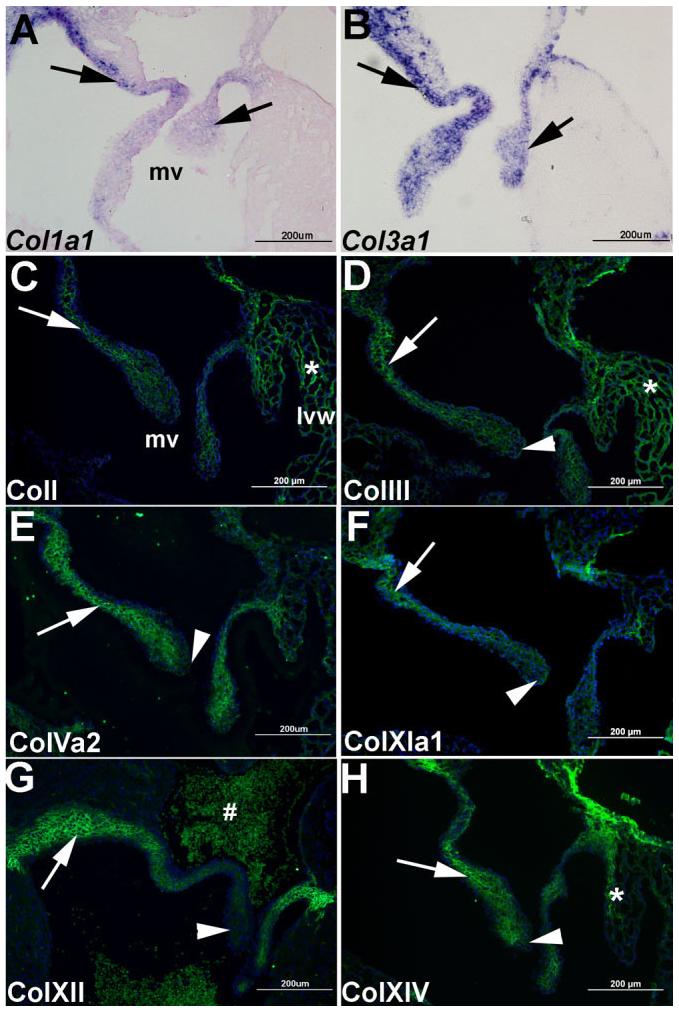

Between E17.5 and neonatal stages, heart valves undergo extensive maturation and further organization of connective tissue (Hinton et al., 2006). TLDA analyses revealed that col1a1, col1a2, col3a1, col5a2, col12a1, and col14a1 transcript levels were amongst the most predominant at this time, and identified significantly increased col11a1 levels at neonatal stages compared to remodeling valves.

Immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization were performed to determine their spatial localization in maturing, neonate valve structures. mRNA expression of fibril-forming collagen types col1a1 (Fig. 3A) and col3a1 (Fig. 3B) is observed throughout the mitral valve leaflets (arrows), further supported at the protein level by immunofluorescence (Fig. 3C,D). In addition, protein expression of other fibril-forming collagens including Va2 (Fig. 3E), and XIa1 (Fig. 3F), and network-forming collagens XII (Fig. 3G) and XIV (Fig. 3H) are also observed throughout maturing neonate valve leaflets at this stage. Interestingly, protein expression of colIII (Fig. 3D), colVa2 (Fig. 3E), colXIa1 (Fig. 3F), colXII (Fig. 3G), and colXIV (Fig. 3H) is notably reduced at the distal tips of the leaflets (arrowhead). In addition to valve expression, colI and colIII are observed in the ventricular myocardium (*, Fig. 3C,D,H). These data highlight the spatial expression of defined collagens in neonatal maturing heart valves.

Fig. 3.

Differential expression of collagens I, III, Va2, XIa1, XII, and XIV in maturing neonate mitral valves. In situ hybridization (A, B) and immunofluorescence (C-H) were used to detect spatial expression of highly expressed collagens in maturing mitral valves in neonatal mice. Col1a1 (A) and col3a1 (B) are expressed throughout the mitral valve leaflets (arrows). By immunofluorescence, collagens I (C), III (D), Va2 (E), XIa1 (F), XII (G), and XIV (H) are detected throughout the mitral valve leaflets (arrow), with reduced expression of colIII, colVa2, colXIa1, colXII, and colXIV observed at the distal tips (arrowhead). Note additional expression of colI, colIII, and colXIV in the ventricular myocardium (*, C, D, H). #, non-specific auto-fluorescent staining of red blood cells. Blue DAPI staining indicates nuclei. mv, mitral valve; lvw, left ventricular wall. Scale bar = 200 μm.

Adult Mitral Valve Structures Show Differential Collagen Expression in Atrial and Ventricular Compartments

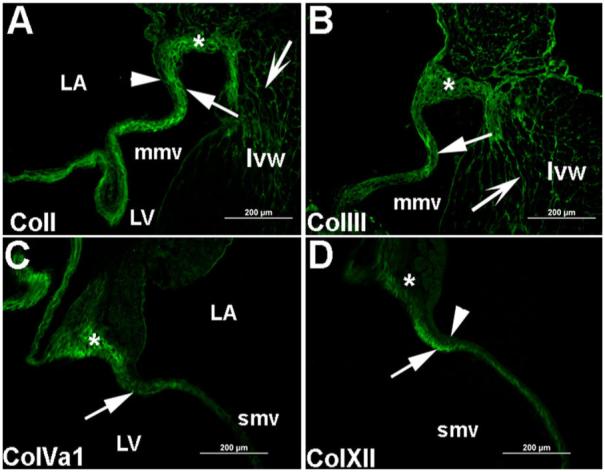

Normal adult heart valves are characterized by compartmentalization of specified ECM within distinct regions of the valve tissue (Hinton et al., 2006). TLDA analysis determined that transcript levels of col1a1, col1a2, col3a1, col5a1 are comparatively high at this stage and therefore to confirm these findings and determine spatial compartmentalization, immunofluorescence was performed. ColI expression is specifically enriched along the ventricular surface of the valve leaflet (arrow, Fig. 4A), but is no longer detected on the atrial surface (arrowhead, Fig. 4A). Similarly, colXII, a network-forming collagen, is detected along the ventricular portion of the valve leaflet (arrow, Fig. 4D). In contrast, colIII is present throughout the valve leaflet (arrow, Fig. 4B), while colVa1 is detected in the proximal portion of the valve leaflet (arrow, Fig. 4C). Interestingly, colI (Fig. 4A), colIII (Fig. 4B), and colVa1 (Fig. 4C) are also highly expressed in the annular regions (*), with additional coII and coIIII expression detected in the ventricular myocardium (concave arrows, Fig. 4A,B). Collectively, these expression patterns demonstrate the high order of collagen matrix compartmentalization in mature and maintained heart valve structures.

Fig. 4.

Adult mitral valves show differential expression in atrial and ventricular compartments of the valve leaflets. Immunofluorescence was performed to detect the spatial expression of collagens I, III, Va1, and XII in adult murine mitral valve leaflets. A: ColI expression is detected in the ventricular surface of the mitral valve leaflet (arrow), the valve annulus (*), and the ventricular myocardium (concave arrow). ColI expression was not observed on the atrial surface of the valve leaflet (arrowhead). B: ColIII is detected throughout the valve leaflet (arrow), in the ventricular myocardium (concave arrow), and the valve annulus (*). C: ColVa1 expression is observed in the proximal portion of the valve leaflet (arrow) and in the annulus of the mitral valve (*). D: Expression of colXII is detected along the ventricular surface of the valve leaflet and almost absent on the atrial leaflet surface (arrowhead) and the annulus (*). Low levels of expression are also observed in the annulus (*). Nuclei are stained blue with DAPI. Scale bar = 200 μm. mmv, mural mitral valve; smv, septal mitral valve; LA, left atria; LV, left ventricle; lvw, left ventricular wall.

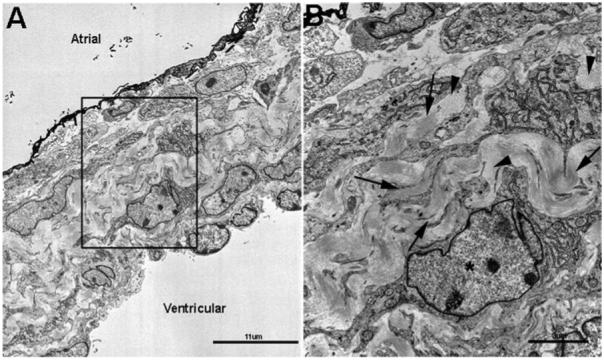

Collagen Fibrils Are Highly Organized in Tight Bundles in Neonate Mitral Valves

Bundles of aligned collagen fibrils can be observed in mitral heart valves from neonate mice using transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 5). In the maturing leaflet, large amounts of ECM containing collagen fibrils appear to surround the fibroblast-like valve interstitial cells (*, Fig. 5B). Collagen fibrils are presented as highly organized, parallel longitudinal bundles (arrows, Fig. 5A), as well as fibril bundles that run perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the heart valve leaflet (arrowheads, Fig. 5B). The high abundance of collagen fibrils (Fig. 5B) are localized towards the ventricular surface of the valve leaflet (Fig. 5A), consistent with the fibrosa matrix layer.

Fig. 5.

Collagen fibrils are highly organized in tight bundles in neonatal mitral valve leaflets. Transmission electron microscopy was used to observe collagen fibril organization at the ultrastructural level in mitral valve leaflets from neonate mice. A: Low magnification of the mitral valve leaflet respective to the atrial and ventricular surface. B: Higher magnification of the boxed area shown in A. Consistent with the fibrosa layer close to the ventricular surface, arrows indicate parallel collagen fibrils, and arrowheads show fibrils running perpendicular to the plane of section.

DISCUSSION

Connective tissues of skin, bone, tendon, and cartilage are composed of highly organized collagen scaffolds that facilitate tissue function, and there is ever emerging data to suggest a similar requirement for collagens in heart valve structures (Bosman and Stamenkovic, 2003; Lincoln et al., 2006a). However, the composition and localization of different collagen types required to establish and maintain valve function has not been fully examined. To address this, we performed TLDA, in situ hybridization, and immunohistochemical studies to investigate the temporal and spatial expression of collagens in murine atrioventricular heart valves at embryonic, neonatal, and adult stages. In this study, the transcript levels of 18 collagen genes were examined and all were detectable during at least one stage of murine heart valve development or maintenance. Our findings show that endocardial cushions at E12.5 contain high levels of col1a1, col2a1, and col3a1 transcripts. During valve matrix remodeling at E17.5, transcript levels of col1a1, col5a1, and col12a1 increase, although col1a1 and col3a1 levels remain predominantly high. The greatest number of significantly increased collagen transcripts was observed in maturing neonatal valves, when collagen proteins begin to show compartmentalization within regions of the valve leaflets. In the adult valves, col1a1, col1a2, and col3a1 transcript levels are the most highly observed. However, col12a1 and coI14a1 are also detected at high levels. At this stage, compartmentalization of connective tissue layers is apparent and differential collagens are observed in annular regions. Collectively, these data identify the temporal and spatial localization of collagen types during important stages of valve formation, maturation, and maintenance that likely contribute to normal heart valve structure and function.

During endocardial cushion formation, the ECM supports proliferation and migration of newly transformed mesenchyme cells into the cardiac jelly, and provides a repository for inductive molecules (Potts and Runyan, 1989; Person et al., 2005). The lower abundance of collagen genes at this stage compared to later time points likely reflects the infiltrative and compliant architecture required for matrix function at this time (Swiderski et al., 1994; Lincoln et al., 2006b; Butcher et al., 2007). As valvulogenesis progresses, primitive valve structures become essential for maintaining unidirectional blood flow as hemodynamic forces increase (Sedmera et al., 1999; Lincoln et al., 2006b; Butcher et al., 2007). This is reflected in the extensive ECM remodeling and significant increases in differential collagen transcript levels in the valves and developing annular regions until the neonatal stages (Lincoln et al., 2004). Deposition of collagens during the remodeling stages appears most active in proximal regions while select collagens, particularly FACITs, appear decreased at the distal tips. The distal tip region, or “free edge” is associated with high levels of proteoglycans in porcine valves (Stephens et al., 2008). This defined architecture of low-level collagens and abundant proteoglycans presumably contributes to a more pliable matrix at the distal tips for leaflet coaptation during the cardiac cycle (Sacks et al., 2002). Between neonatal and adult stages, organization of specific collagen proteins along the atrial and ventricular surfaces is very apparent. In line with other connective systems, it is suggested that the network-forming colXII may stabilize colI fibrils along the ventricular surface and provide a more elastic matrix adjacent to the greatest hemodynamic forces (Iimoto et al., 1988; Koch et al., 1995; Young et al., 2002; Butcher et al., 2007). The overall reduction in collagen gene expression in the adult is similar to that previously described in human aortic valves and is likely due to the decrease in hemodynamic pressure observed after birth following separation into the pulmonary and systemic circulatory systems (Aikawa et al., 2006). Collectively, these data suggest that distribution and organization of multiple collagen types are highly adaptive to ensure a defined and homeotic matrix required for function during stages of embryonic heart valve formation and adult valve maintenance.

The requirement of collagen type, assembly, distribution, and organization for connective tissue function is well established and is supported by observations of tissue dysfunction in mouse models and human patients harboring mutations in collagen genes (Malfait and De Paepe, 2005; Wenstrup et al., 2006; Grau et al., 2007). Mitral valve prolapse, or valvular insufficiency, has been reported in many forms of collagen mutation diseases associated with primary defects in bone, cartilage, tendon, and skin (Liberfarb et al., 1986; Glesby and Pyeritz, 1989; Lincoln et al., 2006a). Several collagens are abundantly expressed in heart valve structures, and despite the availability of mouse models carrying mutations in collagen genes, the roles played by different collagen classes during valvulogenesis in vivo warrant further investigation (Aszódi et al., 2000; Lincoln et al., 2006a). Insights into detrimental effects on heart valve structure and function following the loss of individual collagens in heart valves may be predicted from the discrete expression patterns revealed in this report. In conclusion, this study has examined the temporal and spatial relationships between fibril-, network-forming, and FACIT collagens during important stages of valve development and maturation and identified collagen genes that may be attributed to currently unappreciated forms of valve pathology.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Tissue Preparation

C57/BL6 mouse embryos were collected at E12.5 and E17.5, with detection of copulation plug considered embryonic day 0.5. E12.5 whole embryos and hearts from E17.5 embryos, 1-day neonate mice, and 2-month-old mice were collected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. Tissue was embedded for 5-μm-thick paraffin wax or 10-μm-thick frozen sectioning. Paraffin sections were deparaffinized in xylene, re-hydrated through a graded ethanol series, and rinsed in PBS as previously described (Lincoln et al., 2004). Frozen sections were stored at -20°C and allowed to dry at 42°C for 20 min and rinsed in 1×PBS prior to immunohistochemical staining or in situ hybridization (Lincoln et al., 2007). All animal procedures were approved and performed in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Taqman Low Density Array (TLDA)

Gene expression was investigated using TaqMan Low Density Array (TLDA). TLDA cards consist of 384 (4×96) wells pre-loaded with selected Taqman oligos for high-throughput, low reaction volume, real-time PCR. Expression of 96 customized genes, including 2 endogenous controls were analyzed in 4 independent cDNA samples collected from wild-type mice at embryonic, postnatal, and adult time points. Following RNA extraction, 1 μg of RNA was subject to cDNA synthesis according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Applied Biosystems). Ten microliters (10 μl) of each cDNA sample was diluted in 90 μl of distilled water and 100 μl of Taqman master mix (no. 4304437, Applied Biosystems) for each experimental run. Four cDNA samples per taqman array card were loaded and 1 μl of reaction mixture was distributed onto each of the wells containing the specific taqman oligo by centrifugation. Standard recommended PCR protocols were performed (50°C for 2 min, 94.5°C for 10 min, 97°C for 30 sec, 59.7°C for 1 min, with steps 3 and 4 repeated for 40 cycles) using the ABI 7900 HT Fast Real-Time PCR System. ΔCT values were determined by normalization to Gapdh using the RQ SDS manager software (Applied Biosystems). For more intuitive representation of the data, approximate transcript copy number was estimated by assuming amplicons doubled during each PCR cycle. Sample wells with a CT count of 40 were excluded from analysis as outliers when more than two standard deviations above the mean of replicates. Statistically significant differences in transcript levels were determined using Student’s t-test (P < 0.05). Collagen gene names are italicized and include corresponding arabic numerals.

Histology and Immunostaining

Tissue sections were prepared as described above, subjected to necessary antigen retrieval (see Table 2), and blocked in 10% heat inactivated goat serum/1×PBS:0.1% Tween 20 for 1 hr at room temperature. Antigen retrieval with bovine testicular hyaluronidase (Sigma) was used at 500 U/ml in phosphate buffer according to the manufacturer’s instructions for 30 min at 37°C. Alternatively, chondroitinase ABC (Sigma, 2 U/ml) was applied for 30 min at 37°C according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primary antibody incubations were carried out overnight at 4°C. Alternatively, tissue sections were incubated in block solution and served as negative controls. Following overnight incubation, sections were washed in 1×PBS and incubated with respective anti-rabbit or anti-mouse Alexa 488 or 568 secondary antibodies at 1:400 dilution for 1 hr at room temperature (see Table 2).

TABLE 2. Summary of Antibody Procedures.

| Antigen | Provider | Embedding method | Antigen retrieval | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collagen I | Abcam | Paraffin | None | 1:200 |

| Collagen III | Rockland | Paraffin | None | 1:200 |

| Collagen Va1 | Dr. David Birk | OCT | Hyaluronidase | 1:200 |

| Collagen Va2 | Dr. David Birk | OCT | Hyaluronidase | 1:200 |

| Collagen Xla1 | Dr. David Birk | OCT | Chondroitinase ABC | 1:200 |

| Collagen XII, XIV | Dr. Manuel Koch | OCT | None | 1:250 |

In Situ Hybridization

Prepared 10-μm-thick frozen sections were subjected to in situ hybridization as previously described (Lincoln et al., 2007). The plasmid used to generate the mouse col1a1-specific riboprobe was a kind gift from Dr. Katherine Yutzey. The col3a1 riboprobe based on the cDNA IMAGE clone no. 5705762 was a generous gift from Dr. Benoit De Crombrugghe.

Electron Microscopy

Hearts subject to electron microscopy were collected at neonatal stages and fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde, 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) for 30 min at room temperature. Hearts were bisected longitudinally and fixed for an additional 2 hr at 4°C, washed in 200 mM phosphate buffer with 0.1% sodium azide, and stored in 1×PBS until embedding. Transmission electron microscopy was performed as described previously (Humphries et al., 2008).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. David Birk, Benoit De Crombrugghe, Stephen Henry, and Katherine Yutzey for their kind contributions of antibodies and in situ hybridization probes, and Dr. Lina Shehadeh for her scientific expertise. This work was supported by James and Esther King Biomedical Research Program (JL-07KN07), NHLBI Training Grant in Cardiovascular Signaling (HL007188, Directed by Dr. James D. Potter), and The Florida Heart Research Institute.

REFERENCES

- Aikawa E, Whittaker P, Farber M, Mendelson K, Padera RF, Aikawa M, Schoen FJ. Human semilunar cardiac valve remodeling by activated cells from fetus to adult: implications for postnatal adaptation, pathology, and tissue engineering. Circulation. 2006;113:1344–1352. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.591768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aszódi A, F. Bateman J, Gustafsson E, Boot-Handford R, Fässler R. Mammalian skeletogenesis and extracellular matrix: What can we learn from knockout mice? Cell Struct Funct. 2000;25:73–84. doi: 10.1247/csf.25.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosman FT, Stamenkovic I. Functional structure and composition of the extracellular matrix. J Pathol. 2003;200:423–428. doi: 10.1002/path.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher JT, McQuinn TC, Sedmera D, Turner D, Markwald RR. Transitions in early embryonic atrioventricular valvular function correspond with changes in cushion biomechanics that are predictable by tissue composition. Circ Res. 2007;100:1503–1511. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.148684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glesby MJ, Pyeritz RE. Association of mitral valve prolapse and systemic abnormalities of connective tissue. A phenotypic continuum. JAMA. 1989;262:523–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grau J, Pirelli L, Yu P, Galloway A, Ostrer H. The genetics of mitral valve prolapse. Clin Genet. 2007;72:288–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross L, Kugel MA. Topographic anatomy and histology of the valves in the human heart. Am J Pathol. 1931;7:445–456. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton RB, Jr, Lincoln J, Deutsch GH, Osinska H, Manning PB, Benson DW, Yutzey KE. Extracellular matrix remodeling and organization in developing and diseased aortic valves. Circ Res. 2006;98:1431–1438. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000224114.65109.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries SM, Lu Y, Canty EG, Kadler KE. Active negative control of collagen fibrillogenesis in vivo: Intracellular cleavage of the type I procollagen propeptides in tendon fibroblasts without intracellular fibrils. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:12129–12135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708198200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iimoto D, Covell J, Harper E. Increase in cross-linking of type I and type III collagens associated with volume-overload hypertrophy. Circ Res. 1988;63:399–408. doi: 10.1161/01.res.63.2.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadler KE, Baldock C, Bella J, Boot-Handford RP. Collagens at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:1955–1958. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M, Bohrmann B, Matthison M, Hagios C, Trueb B, Chiquet M. Large and small splice variants of collagen XII: differential expression and ligand binding. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:1005–1014. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.4.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klewer SE, Krob SL, Kolker SJ, Kitten GT. Expression of type VI collagen in the developing mouse heart. Dev Dyn. 1998;211:248–255. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199803)211:3<248::AID-AJA6>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberfarb RM, Goldblatt A, Opitz JM, Reynolds JF. Prevalence of mitralvalve prolapse in the stickler syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1986;24:387–392. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320240302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln J, Alfieri CM, Yutzey KE. Development of heart valve leaflets and supporting apparatus in chicken and mouse embryos. Dev Dyn. 2004;230:239–250. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln J, Florer JB, Deutsch GH, Wenstrup RJ, Yutzey KE. ColVa1 and ColXIa1 are required for myocardial morphogenesis and heart valve development. Dev Dyn. 2006a;235:3295–3305. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln J, Lange AW, Yutzey KE. Hearts and bones: Shared regulatory mechanisms in heart valve, cartilage, tendon, and bone development. Dev Biol. 2006b;294:292–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln J, Kist R, Scherer G, Yutzey KE. Sox9 is required for precursor cell expansion and extracellular matrix organization during mouse heart valve development. Dev Biol. 2007;305:120–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Wu H, Byrne M, Krane S, Jaenisch R. Type III collagen is crucial for collagen I fibrillogenesis and for normal cardiovascular development. PNAS. 1997;94:1852–1856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löhler J, Timpl R, Jaenisch R. Embryonic lethal mutation in mouse collagen I gene causes rupture of blood vessels and is associated with erythropoietic and mesenchymal cell death. Cell. 1984;38:597–607. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malfait F, De Paepe A. Molecular genetics in classic Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Sem Med Genet. 2005;139C:17–23. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malfait F, Symoens S, Coucke P, Nunes L, De Almeida S, De Paepe A. Total absence of the {alpha}2(I) chain of collagen type I causes a rare form of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome with hypermobility and propensity to cardiac valvular problems. J Med Genet. 2006;43:e36. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.038224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Person AD, Klewer SE, Runyan RB. Cell Biology of Cardiac Cushion Development. Int Rev Cytol. 2005;243:287–335. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(05)43005-3. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts JD, Runyan RB. Epithelial-mesenchymal cell transformation in the embryonic heart can be mediated, in part, by transforming growth factor β. Dev Biol. 1989;134:392–401. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabkin-Aikawa E, Mayer, John E, Schoen FJ. Heart valve regeneration. Regen Med. 2005;II:141–179. doi: 10.1007/b100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosamond W, Flegal K, Friday G, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Ho M, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lloyd-Jones D, McDermott M, Meigs J, Moy C, Nichol G, O’Donnell C, Roger V, Rums-feld J, Sorlie P, Steinberger J, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Hong Y. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2007 update: A report from the american heart association statistics committee and stroke statistics subcommittee. Circulation. 2007;115:e69–171. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.179918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks MS, He Z, Baijens L, Wanant S, Shah P, Sugimoto H, Yoganathan AP. Surface strains in the anterior leaflet of the functioning mitral valve. Ann Biomed Eng. 2002;30:1281–1290. doi: 10.1114/1.1529194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedmera D, Pexieder T, Rychterova V, Hu N, Clark EB. Remodeling of chick embryonic ventricular myoarchitecture under experimentally changed loading conditions. Anat Rec. 1999;254:238–252. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(19990201)254:2<238::AID-AR10>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw LM, Olsen BR. FACIT collagens: Diverse molecular bridges in extracellular matrices. Trends Biochem Sci. 1991;16:191–194. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan S, Sherratt MJ, Hodson N, Shuttleworth CA, Kielty CM. Expression and supramolecular assembly of recombinant {alpha}1(VIII) and {alpha}2(VIII) collagen homotrimers. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21469–21477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305805200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens EH, Chu CK, Grande-Allen KJ. Valve proteoglycan content and glycosaminoglycan fine structure are unique to microstructure, mechanical load and age: Relevance to an age-specific tissue-engineered heart valve. Acta Biomater. 2008;4:1148–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiderski RE, Daniels KJ, Jensen KL, Solursh M. Type II collagen is transiently expressed during avian cardiac valve morphogenesis. Dev Dyn. 1994;200:294–304. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002000404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinkle BT, Wenstrup RJ. A genetic approach to fracture epidemiology in childhood. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Sem Med Genet. 2005;139C:38–54. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenstrup RJ, Florer JB, Brunskill EW, Bell SM, Chervoneva I, Birk DE. Type V collagen controls the initiation of collagen fibril assembly. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53331–53337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409622200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenstrup RJ, Florer JB, Davidson JM, Phillips CL, Pfeiffer BJ, Menezes DW, Chervoneva I, Birk DE. Murine model of the ehlers-danlos syndrome: Col5a1 Haploinsufficiency disrupts collagen fibril assembly at multiple stages. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:12888–12895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511528200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young BB, Zhang G, Koch M, Birk DE. The roles of types XII and XIV collagen in fibrillogenesis and matrix assembly in the developing cornea. J Cell Biochem. 2002;87:208–220. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]