Abstract

A fundamental feature of modular polyketide synthases (PKSs) is the highly predictable relationship between the domain order and the chemical functional groups of resultant polyketide products. Sequence analysis and biochemical characterization of the leinamycin (LNM) biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces atroolivaceus S-140 has revealed a gene, lnmJ, that encodes five PKS modules but with six acyl carrier protein (ACP) domains. The LnmJ PKS module-6 contains two ACP domains, ACP6-1 and ACP6-2, separated by a C-methyltransferase domain. Site-directed mutagenesis experiments were carried out with each of these ACP’s to test alternative mechanisms proposed for their role in polyketide chain elongation. The in vivo results revealed a new type of polyketide chain “skipping” mechanism, in which either ACP is sufficient for LNM biosynthesis. Biochemical characterization in vitro showed that both ACPs can be loaded with a malonate extender unit by the LnmG acyl transferase; however, ACP6-2 appears to be preferred because the loading efficiency is about 5-fold that of ACP6-1. The results are consistent with ACP6-2 being used for the initial chain elongation step wth ACP6-1 being involved in the ensuing C-methylation process. These findings provide new insights into the polyketide chain skipping mechanism for modular PKSs.

Polyketides are a large group of microbial natural products that include many clinically valuable drugs such as erythromycin (antibacterial), rapamycin (immunosuppressant), and epothilone (anticancer agent). Typically, they are biosynthesized from short carboxylic acids by sequential condensation catalyzed by polyketide synthases (PKSs).1,2 Multimodular type I PKSs consist of sets of active site domains organized into modules with each module containing a minimum of three domains. The chain building substrates are selected and activated by an acyl transferase (AT) domain, transferred to the phosphopantetheine side chain of the acyl carrier protein (ACP) domain to form a thioester, and then covalently linked to the growing polyketide by a ketosynthase (KS) domain, which catalyzes a decarboxylative Claisen condensation to form carbon-carbon bond as an enzyme-bound β-ketothioester. Other domains, such as ketoreductase (KR), dehydratase (DH), enoyl reductase (ER), and methyl transferase (MT) domains, may also be present in a specific module and are responsible for modification(s) of the nascent β-keto group.1,2 The order of modules in such PKS enzymes dictates the sequence of biosynthetic events, and the variation of domains within a module affords the structural diversity observed in the resultant polyketide products.1,2 The co-linearity between the modularity of enzyme activities and the structure of the resultant products provides the molecular basis for combinatorial manipulation of type I PKSs to generate polyketide structural diversity.3–6

Additional domains have occasionally been found in certain PKSs that do not seem to be required to provide the functionality that is found in the final polyketide products. The “extra” domains in some cases appear to be inactive due to the lack of critical amino acids that consist of the active sites, such as the DH and KR domains in module 8 of the EpoE protein, the DH and ER domains in module 9 of the EpoF protein,7 and the KR domain in module 3 of the PikAII protein.8 More often, the extra domains seem to be functional because they have all the highly conserved residues and motifs of fully functional domains, such as the two DH domains and one ER domain of the nanchangmycin PKS,9 the four DH domains of the FK520 PKS,10 and the one KR domain of the avermectin PKS.11 These discrepancies between module organization and product structure hinder the quest for full understanding of the biosynthetic mechanism and provide obstacles for the rational engineering of type I PKSs to produce novel polyketides.

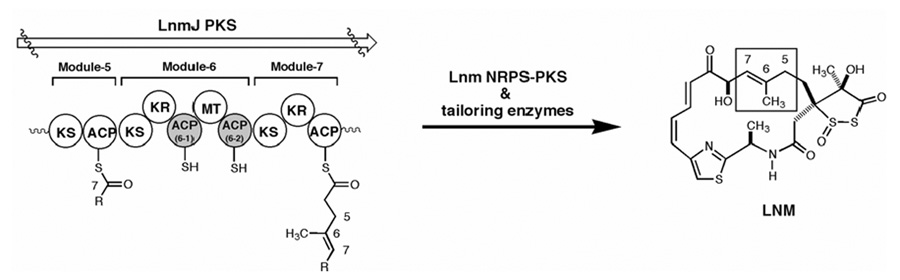

Leinamycin (LNM, Figure 1) is a hybrid peptide-polyketide natural product with antitumor activity.12–14 Genetic and biochemical characterization of the lnm biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces atroolivaceus S-140 has revealed that LNM is biosynthesized by a hybrid nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS)-PKS system consisting of two NRPS modules and six PKS modules.15–17 In addition to being characterized as a novel “AT-less” type I modular PKS system,16 several other interesting aspects were found from the gene sequence analysis.17 In particular, LnmJ PKS module-6 has two ACP domains, ACP6-1 and ACP6-2, separated by an MT domain that is believed to govern introduction of the C-6 methyl group (Figure 1). According to the conventional model for the PKS mechanism, only one of these ACPs should be necessary for the polyketide elongation step.1,2 We have examined the role of each ACP using in vivo site-directed mutagenesis combined with in vitro biochemical assays and now report the discovery of an unusual chain “skipping” mechanism used by the LnmJ PKS for LNM biosynthesis. The experimental results show that the two ACPs in LnmJ PKS module-6 are functionally interchangeable and that either one is sufficient for LNM biosynthesis. In addition, the results of biochemical assays are consistent with LmnG AT using ACP6-2 over ACP6-1 when loading malonyl-CoA, which could mean that ACP6-2 is used for the initial chain elongation step while ACP6-1 is involved in the ensuing C-methylation process.

Figure 1.

Structure of LNM and domain organization of the LnmJ PKS module-5, -6, and -7 featuring two ACPs in module-6. The moiety that is biosynthesized by LnmJ PKS module-6 is boxed. ACP, acyl carrier protein; KR, ketoreductase; KS, ketosynthase; MT, methyl transferase.

Results and Discussion

Alternative Mechanisms for Polyketide Chain Elongation by LnmJ PKS Module-6

LNM, an antitumor antibiotic, is a hybrid peptide-polyketide natural product with an unusual 1,3-dioxo-1,2-dithiolane moiety that is spiro-fused to an 18-membered macrolactam ring, a molecular architecture that has not been found to date in any other natural product.12,13 Cloning, sequencing, genetic and biochemical characterization of the lnm biosynthetic gene cluster from S. atroolivaceus S-140 revealed a novel “AT-less” type I PKS system featured with several unusual aspects for domain organization.15–17 While six PKS modules are present, the LnmJ PKS module-6 has two ACP domains, ACP6-1 and ACP6-2, one of which seems to be unnecessary for LNM biosynthesis (Figure 1). A question therefore arises about the role of the two ACP domains in module-6: are they both involved in polyketide chain transfer from LnmJ PKS module-5 to module-7 or is one of them used for a different purpose, such as C-methylation of the biosynthetic intermediate bound to LnmJ PKS module-6?

Five distinct mechanisms can be proposed to explain the chain elongation step catalyzed by LnmJ PKS module-6. Each mechanism can be distinguished by its difference regarding the involvement of the ACP domains in the chain elongation and transfer from the KS domain of module-5 to the KS domain of module-7 and C-methylation of the biosynthetic intermediate bound to module-6 (Figure 2).

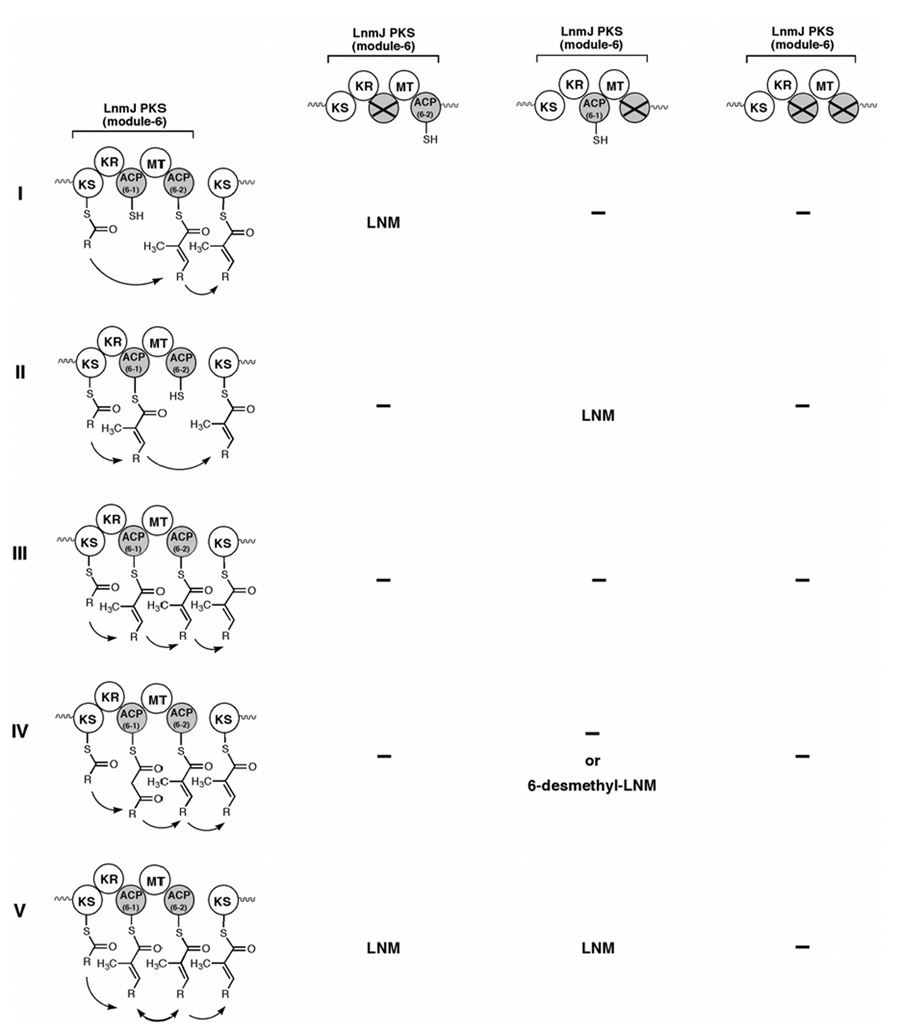

Figure 2.

Alterative mechanisms proposed for LnmJ PKS catalyzed polyketide chain transfer from module-5 to module-6 and module-7. I, only ACP6-2 is functional; II only ACP6-1 is functional; III, both ACPs are functional and necessary; IV, both ACPs are functional with each mediating the chain elongation step and the ensuing C-methylation step, respectively; V, both ACPs are functionally equivalent but one is sufficient (i.e., the chain skipping model) for LNM biosynthesis. LNM or 6-desmethyl-LNM, mutants that produce LNM or 6-desmethyl-LNM; (—), no production of LNM metabolite. See figure 1 legend for domain abbreviations.

Mechanisms I and II: Only ACP6-1 or ACP6-2 Is Functional

Although both ACPs of the LnmJ PKS module-6 contain the highly conserved GVDS motif, in which the Ser residue can be post-translationally modified by the covalent attachment of the 4'-phosphopantetheine group,18–20 it is possible that only one of the two ACPs is functional for LNM biosynthesis. In this case, mutation of the active site residue Ser of the non-functional ACP into Ala should have no obvious effect on LNM biosynthesis. In contrast, LNM biosynthesis would be abolished in the Ser to Ala mutant of the essential ACP, because the polyketide chain could not directly be transferred from the KS domain of module-5 to the KS domain of module-7 without a functional ACP (Figure 2, entries I and II).

Mechanism III: Both ACP Domains Are Functional and Necessary

In this mechanism, the polyketide chain is first attached to ACP6-1 from the KS domain of module-6 as a consequence of normal chain elongation and methylation, then transferred to ACP6-2 before loading onto the active site residue Cys of the KS domain in module-7. This step-by-step mechanism needs both ACPs; therefore, either of the above Ser to Ala mutations would abolish LNM biosynthesis (Figure 2, entry III).

Mechanism IV: Both ACP Domains Are Functional with Each Mediating the Chain Elongation Step and the C-Methylation Step, Respectively

This mechanism is similar to mechanism III wherein both ACPs are involved in the chain elongation, C-methylation, and chain transfer steps. First, the polyketide chain is attached to ACP6-1 as a consequence of only chain extension catalyzed by the KS domain of module-6, then transferred to ACP6-2 followed by C-methylation before loading onto the active site residues Cys of the KS domain of module-7. In this mechanism, both ACPs are essential: the Ser to Ala mutation of ACP6-1 will abolish LNM production because it is necessary for chain elongation; mutation of ACP6-2 may abolish LNM production or produce 6-demethyl-LNM if the desmethyl intermediate bound to ACP6-1 could be recognized and processed by the rest of the LNM biosynthetic machinery (Figure 2, entry IV).

Mechanism V: Chain “Skipping” Model in Which Both ACPs Are Functional But One of Them Is Sufficient

In this mechanism the two ACPs are used interchangeably, with either one being enough for LNM biosynthesis. Inactivation of either ACP would not affect LNM production, but when inactivated simultaneously, LNM production would be abolished (Figure 2, entry V).

Construction of LnmJ PKS Module-6 ACP Active Site-directed Mutant Strains

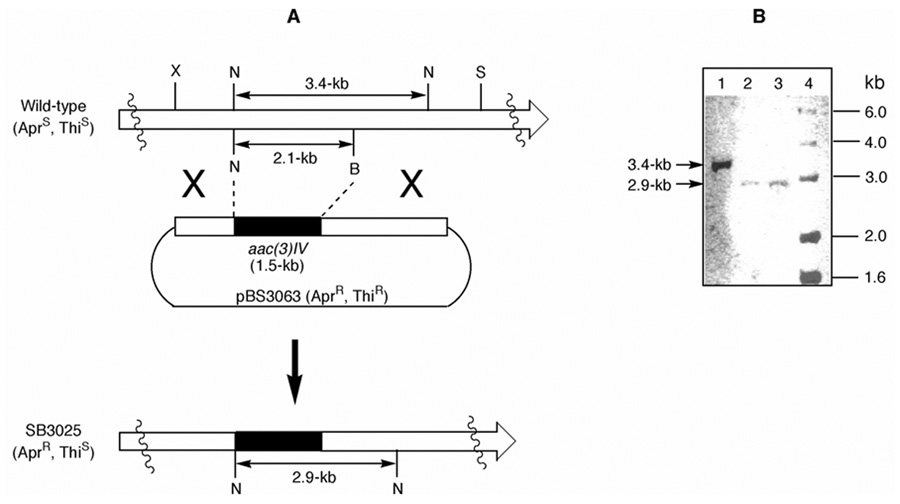

To distinguish among these mechanistic proposals, site-directed mutagenesis was carried out in vitro to replace the Ser active site residue of ACP6-1 (Ser3193) and ACP6-2 (Ser3684). Two-step gene replacement experiments were used to introduce each site-directed mutant ACP into module-6 of the chromosomal lnmJ PKS gene. First, a mutated lnmJ plasmid, pBS3063, was constructed and introduced into S. atroolivaceus to select for the S. atroolivaceus SB3025 mutant strains that were apramycin-resistant and thiostrepton-sensitive (Figure 3A). The genotype of S. atroolivaceus SB3025 mutant strains, in which the ACP6-1 - MT- ACP6-2 domains of the LnmJ PKS module-6 were substituted with the aparmycin-resistance gene, aac(3)IV, was confirmed by Southern analysis. Genomic DNA from both the S. atroolivaceus wild-type and SB3025 mutant strains were digested with NcoI and hybridized with the 3.4-kb NcoI fragment of lnmJ as a probe. While the wild-type strain yielded a distinct signal at 3.4 kb, this fragment was shifted to 2.9 kb in the SB3025 mutant strain as would be predicted for the replacement of the 2.1-kb NcoI-BamHI fragment of lnmJ by the 1.5-kb aac(3)IV cassette (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Inactivation of lnmJ by gene replacement. (A) Construction of the lnmJ gene replacement mutant and restriction maps of S. atroolivaceus wild-type and SB3025 mutant strains. (B) Southern analysis of the wild-type (lane 1) and SB3025 (lanes 2 and 3 for two individual isolates) genomic DNAs digested with NcoI using the 3.4-kb lnmJ fragment as a probe. Lane 4, molecular weight standards. AprR, apramycin-resistant; AprS, apramycin-sensitive; ThiR, thiostrepton-resistant; ThiS, thiostrtepton-sensitive; B, BamHI; N, NcoI; S, SphI; X, XbaI.

Plasmids pBS3068, pBS3069, and pBS3070, in which the active site residue Ser of ACP6-1 (pBS3068) or ACP6-2 (pBS3069), or both ACP6-1 and ACP6-2 (pBS3070), had been changed to Ala, respectively, were then introduced into the BS3025 strain stepwise by first isolating the single-crossover mutants with apramycin-resistant and thiostrepton-resistant phenotype, followed by serial transfer in the absence of antibiotic selection to obtain the double-crossover mutants with an apramycin-sensitive and thiostrepton-sensitive phenotype. The resulting S. atroolivaceus SB3026 (from pBS3068), SB3027 (from pBS3069), and SB3028 (from pBS3070) mutant strains contained the entire lnm gene cluster in which the active site of ACP6-1, ACP6-2, or both ACP6-1 and ACP6-2, respectively, were inactivated by the Ser to Ala mutation. The expected genotypes of these mutant strains were confirmed by PCR amplification followed by DNA sequencing.

The Metabolite Profile of the Fermented Mutants Validating the Chain “Skipping” Mechanism

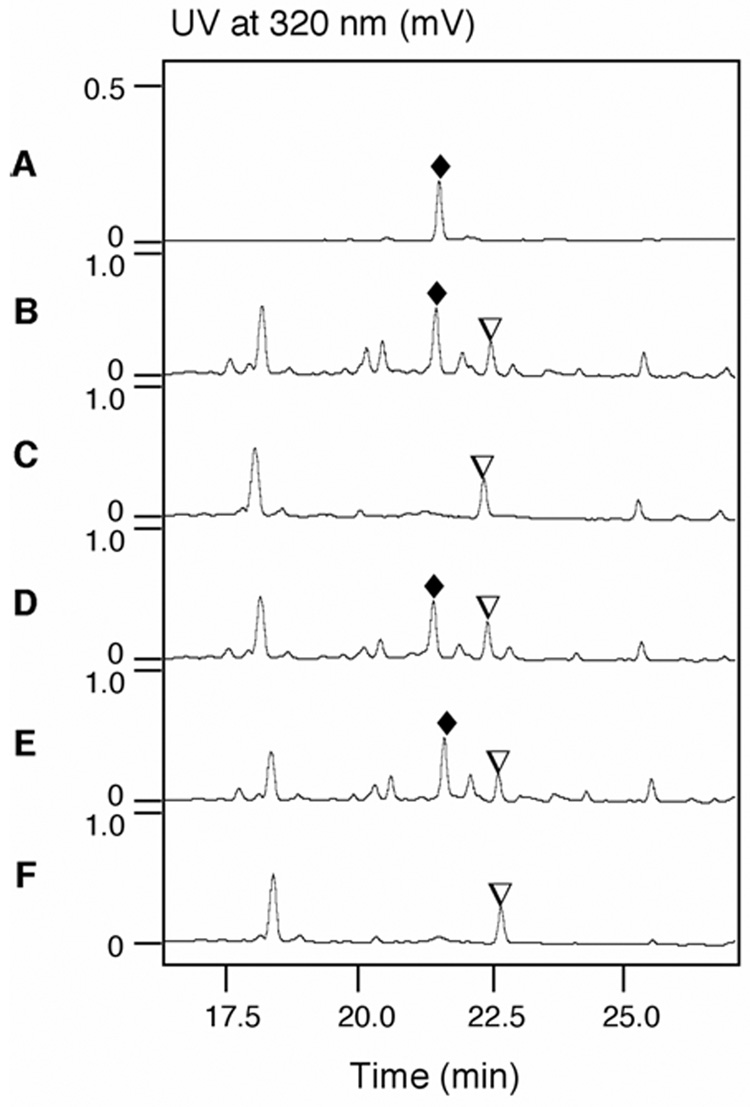

The S. atroolivaceus site-directed mutant strains SB3026, SB3027, and SB3028 were fermented under standard conditions with the wild-type strain as a positive control and the SB3025 mutant strain (i.e., both ACPs as well as the MT domain were deleted) as a negative control. Fermentation culture extracts were analyzed by HPLC and electron-spray ionization-mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) for LNM production.15–17 While LNM production was readily detected from the wild-type (Figure 4B) and was completed abolished in the ACP-deletion mutant strain SB3025 (Figure 4C), the two mutants SB3026 and SB3027 with only one inactivated ACP in LnmJ PKS module-6 still produce as much LNM as the wide-type strain (Figure 4B vs 4D and 4E), and the SB3028 mutant with both ACPs of LnmJ PKS module-6 inactivated completely lost the ability to produce LNM (Figure 4F). These results suggest that each ACP in LnmJ PKS module-6 can functionally replace the other one; i.e., either ACP is sufficient for normal LNM biosynthesis. Therefore the chain “skipping” mechanism (Figure 2, entry V) appears to be used in the polyketide chain elongation and transfer process from the ACP domain of module-5 to the KS domain of module-7 during LNM biosynthesis.

Figure 4.

HPLC analysis of LNM production: LNM standard (A) and S. atroolivaceus S-140 wild-type (B) and recombinant strains SB3025 (C), SB3026 (D), SB3027 (E), and SB3028 (F). (♦), LNM; (▽), an unidentified metabolite whose production is independent to LNM biosynthesis.

In vitro Biochemical Assays Confirming that Both ACPs of the LnmJ PKS Module-6 Can Be Loaded by the LmnG AT But with Different Efficiency

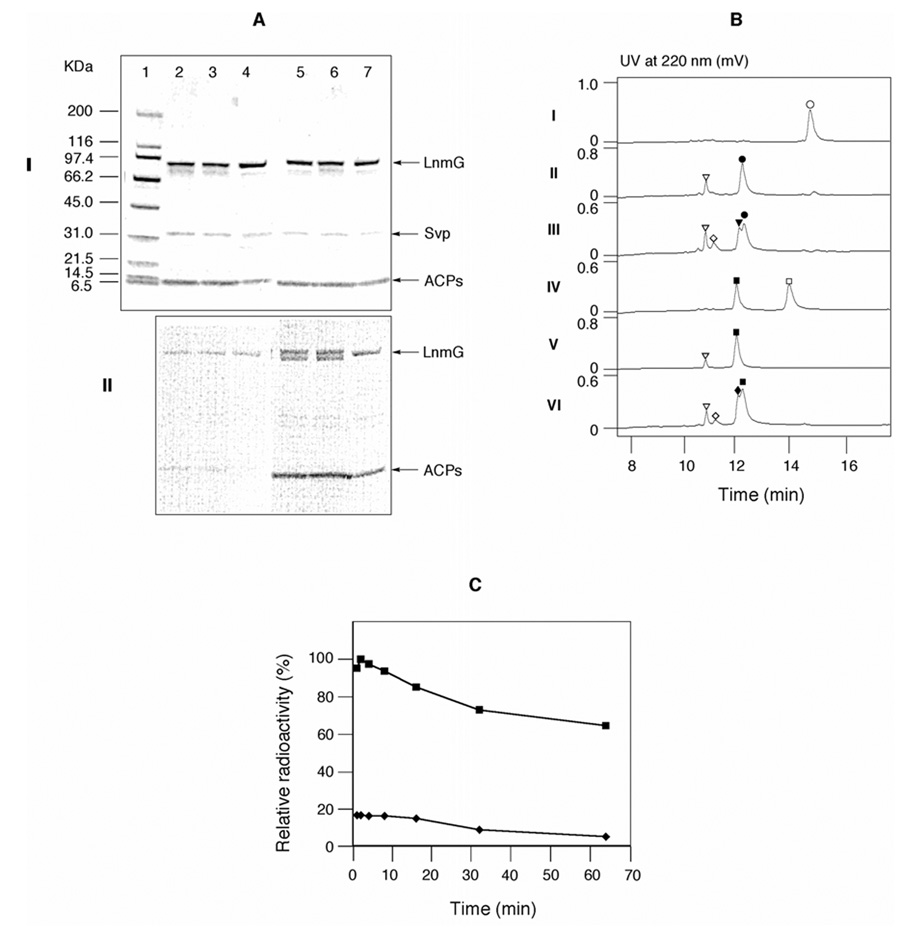

The results of the site-directed mutagenesis experiments support the operation of a chain skipping mechanism, but the individual contribution of each of the two ACPs in LnmJ PKS module-6 could not be assessed, because both single-site mutants produced almost the same level of LNM as the wide-type strain. To examine the individual role of each ACP domain, LnmJ ACP6-1 and ACP6-2 domains as well as the LnmG AT were overproduced in E. coli and purified, and the resultant proteins were utilized for standard in vitro biochemical assays.16 Streptomyces verticillus phosphopantetheinyl (4’-PP) transferase Svp was used to convert the apo-ACPs into the functional holo-form.20 After incubation of holo-ACPs with [2-14C]malonyl CoA and purified LnmG, the reaction mixtures were subjected to SDS-PAGE separation and phosphorimaging to detect loading of the [2-14C]malonyl group onto the 4’-PP groups of the ACPs (Figure 5A). Alternatively, reaction mixtures from experiments with non-radioactive malonyl CoA were subjected to HPLC (Figure 5B) and ESI-MS analysis to confirm formation of the predicted molecular species.16

Figure 5.

In vitro assays of LnmG-catalyzed loading of malonyl CoA to LnmJ ACP6-1 and ACP6-2. (A) Incubation of ACP6-1 and ACP6-2 with [2-14C]malonyl CoA and LnmG as visualized on a 4– 15 % SDSPAGE (I) and by phosphorimaging (II). Lane 1, molecular weight standards; lanes 2, 3, and 4, ACP6-1 with incubation time of 2, 10, 60 min; lanes 5, 6, and 7, ACP6-2 with incubation time of 2, 10, 60 min. (B) HPLC analysis of LnmG-catalyzed loading of malonyl CoA to ACP6-1 (I, II, III) and ACP6-2 (IV, V, VI). I and IV, negative controls in the absence of Svp; II and V, negative controls in the absence of LnmG; III and VI, complete assays. (○), apo-ACP6-1; (●), holo-ACP6-1; (τ), malonyl-S-ACP6-1; (□), apo-ACP6-2; (■), holo-ACP6-2; (♦), malonyl-S-ACP6-2; (▽), SvP; (◊), LnmG. (C), Time course of LnmG-catalyzed loading of [2-14C]malonyl CoA to ACP6-1 (♦) and ACP6-2 (■) as determined by scintillation counting.

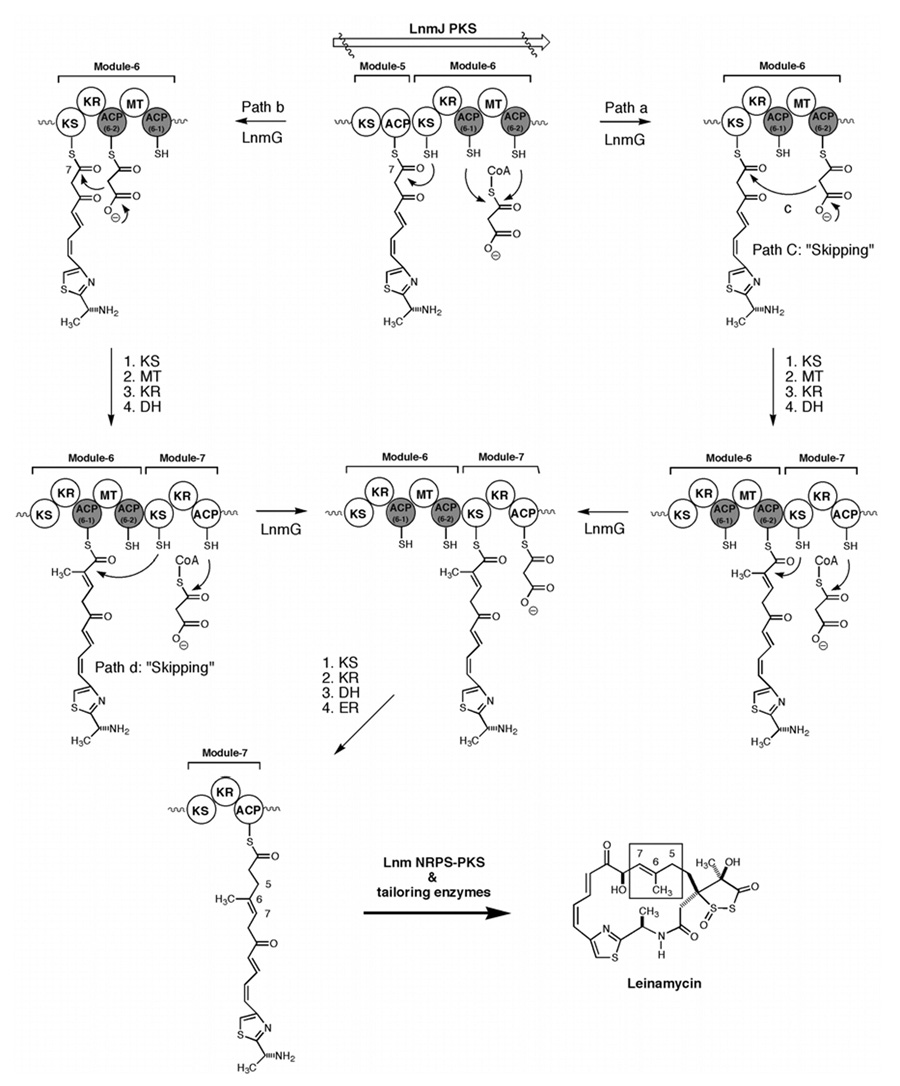

Although both ACPs of LnmJ PKS module-6 were found to be loaded with the radioactive chain extender unit, malonyl CoA, by the LnmG AT, the loading efficiency is clearly quite different as shown in Figure 5A. LnmG appears to prefer ACP6-2 more than ACP6-1. Using a semi-quantitative assay under the same conditions, we found that on the basis of the relative amount of radioactivity in the acylated ACPs as a function of reaction time, the loading efficiency for ACP6-1 is approximately 80% less than that of ACP6-2 (Figure 5C). These results are consistent with LnmG using ACP6-2 for the polyketide chain elongation in the normal biosynthetic process (Figure 6, path a), although ACP6-2 can be recognized by LnmG and consequently be functional for LNM biosynthesis (Figure 6, path b).

Figure 6.

The proposed domain skipping model for LnmJ PKS catalyzed biosynthesis of LNM. The two ACPs in module-6 can functionally replace each other and either one is sufficient for LNM biosynthesis (path a or b), requiring domain skipping at path c or d. Path a is preferred during normal LNM biosynthesis on the basis of LnmG selectivity. DH, dehydratase; ER, enoyl reductase; other domain abbreviation, see figure 1 legend. The origins for the proposed DH activity in module-6 and DH and ER activities in module-7 remain to be established.

ACP-to-ACP Chain Skipping Found in Other Natural and Engineered Modular PKSs

The results reported here represent a novel type of polyketide chain skipping mechanism, possibly to evolve a useful function for the additional core ACP domain in one PKS module. ACP-to-ACP chain transfer has been observed before in an engineered PKS system.21 When an engineered PKS, consisting of the loading module and the extension modules of the erythromycin PKS module 1, the rapamycin PKS module 2, and the erythromycin PKS module 2, was expressed in Saccharopolyspora erythraea strain JC2, the expected tetraketide lactones were produced in low yield and triketide lactones were the major products, which resulted from ACP skipping.22 This was confirmed by site-directed mutagenesis of the KS and ACP domains of the rapamycin PKS module, which revealed a chain skipping process by direct ACP-to-ACP transfer in the engineered PKS.21

The pikromycin PKS from Streptomyces venezuelae contains six extension modules distributed among the four multienzyme polypeptides, PikAI-AIV, which catalyze the biosynthesis of both 12- and 14-membered ring macrolactones.11 Expression of pikAIV to produce the intact, full length PikAIV protein results in the synthesis of a 14-membered ring macrolactone, whereas expression of pikAIV produces an amino-terminal truncated PikAIV protein leading to the synthesis of a 12-membered ring macrolactone.23 A skipping model for chain transfer from PikAIII ACP5 to PikAIV ACP6 was proposed to explain how one PKS system could form two polyketide products.24

Multiple ACP domains have also been found in modules of the mupiricin PKS where some of them appear to be dispensable or can be used interchangeably, as in LnmJ PKS module-6.25 However, direct biochemical evidence of their role has not been described. Here, in the LnmJ PKS, we have provided convincing data supporting a naturally occurring chain skipping mechanism.

In summary, polyketides, a large group of natural products including many therapeutically valuable drugs, are constructed from short carboxylic acid precursors by modular type I PKSs arranged in an assembly-line architecture. Understanding the mechanism of catalysis by PKS enables manipulation of polyketide biosynthetic pathways to produce new “unnatural” natural products with many possible properties previously unattainable. The LnmJ PKS from S. atroolivaceus contains five PKS modules but with six ACP domains, providing an excellent opportunity to explore modularity of PKS and co-linearity between PKS domain organization and structure of the resultant polyketide product. By combining in vivo site-directed mutagenesis with in vitro biochemical assays, we established a novel polyketide chain skipping model to explain the role of the two ACP domains in LnmJ PKS module-6 for LNM biosynthesis. In this model, both ACP6-1 and ACP6-2 in PKS module-6 can functionally replace each other but ACP6-2 is preferred by the LnmG AT during the loading of the malonyl CoA extender unit (Figure 6). Although we still do not understand the consequence of this skipping mechanism and what is the metabolic advantage of the extra ACP domain, these findings are the first to establish this mechanism and provide new insights into understanding the polyketide chain elongation and transfer process and the role of an additional domain in modular type I PKSs in polyketide biosynthesis.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Bacterial Strains, Culture Conditions, and LNM Production, Isolation, and Analysis

E. coli DH5α was used as a host for the manipulation of plasmid DNA and grown in LB medium.26 Authentic LNM standard was kindly provided by Kyowa Hakko Kogyo, Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). S. atroolivaceus S-140 growth, conjugation, and fermentation and LNM production, isolation, and HPLC and ESI-MS analysis have been described preciously.15–17

Generation of Site-directed LnmJ PKS ACP6-1 and ACP6-2 Singly Inactivated and ACP6-1 and ACP6-2 Doubly Inactivated Mutant Strains

In the first round gene replacement to construct the SB3025 mutant strain, A 5.3-kb XbaI-SphI fragment of lnmJ containing PKS module-6 was first cloned from pBS300715 and moved into the same site of pSET15127 to afford pBS3062. An internal 2068-bp NcoI-BamHI fragment from pBS3062 containing the ACP6-1-MT-ACP6-2 domains of PKS module-6 was then replaced with the apramycin-resistance gene, aac(3)IV,28 to yield pBS3063 (Figure 3A). Introduction of pBS3063 into S. atroolivaceus S-140 by conjugation and selection for apramycin-resistance and thiostrepton-sensitive phenotype according to established procedures15–17 yielded the double-crossover mutant strain SB3025, whose genotype was confirmed by Southern analysis (Figure 3B).26

In the second round gene replacement to isolate the ACP site-directed mutant strains SB3026, SB3027, and SB3028, site-directed mutagenesis plasmids were all derived from pBS3062, and the PCR-amplified fragments were sequenced to confirm sequence fidelity. To mutate ACP6-1 (Ser3193Ala), a 1.3-kb NotI-KpnI fragment that contains ACP6-1 was first cloned from pBS3062 and moved into the same sites of pBluescript II SK (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) to afford pBS3064. Site-directed mutagenesis of the Ser active site residue of ACP6-1 was carried out by using the site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) with the following pair of PCR primers (5′- G TTC GGC GTG GAC GCC CTG GTG AGC CTC and 5’-GAG GCT CAC CAG GGC GTC CAC GCC GAA C -3′, the mutated codon is unlined) to afford pBS3065.

To mutate ACP6-2 (Ser3684Ala), a 1.5-kb KpnI-PstI fragment that contains ACP6-2 was cloned from pBS3062 and moved into the same sites of pSP72 (Promega, Madison, WI) to produce pBS3066. Site-directed mutagenesis of the Ser active site residue of ACP6-2 was similarly carried out by using the site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) with the following pair of PCR primer pairs (5′- C TTC GGG GTC GAC GCG CTG GTG AGC C and 5’-G GCT CAC CAG CGC GTC GAC CCC GAA G -3′, the mutated codon is underlined) to yield pBS3067.

To construct the ACP6-1 single mutant plasmid pBS3068, the 1.3-kb NotI-KpnI fragment from pBS3065, which contains the mutated ACP6-1, and the 1.5-kb KpnI-PstI fragment from pBS3066, which contains the wild-type ACP6-2, were combined and ligated into the NotI and PstI sites of pBS3062. To construct the ACP6-2 single mutant plasmid pBS3069, the 1.3-kb NotI-KpnI fragment from pBS3064, which contains the wild-type ACP6-1, and a 1.5-kb KpnI-PstI fragment from pBS3067, which contains the mutated ACP6-2, were combined and ligated into the NotI and PstI sites of pBS3062. Finally, to construct the ACP6-1 and ACP6-2 double mutant plasmid pBS3070, the 1.3-kb NotI-KpnI fragment from pBS3065, which contains the mutated ACP6-1, and the 1.5-kb KpnI-PstI fragment from pBS3067, which contains the mutated ACP6-2, were combined and ligated into the NotI and PstI sites of pBS3062.

To isolate the site-directed ACP mutant strains, plasmids pBS3068, pBS3069, and pBS3070 were introduced into S. atroolivaceus BS3025, respectively, by first selecting the apramycin-resistant and thiostrepton-resistant phenotype to isolate the single-crossover mutants.15–17 The single-crossover mutants were then grown in liquid TSB medium (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) for three rounds and plated onto solid TSB medium, both in the absence of any antibiotics. The resultant colonies were finally selected on TSB plates with apramycin (finial concentration of 50 µg/mL), thiostrepton (final concentration of 25 µg/mL), or no antibiotic. Colonies that were apramycin-sensitive and thiostrepton-sensitive were identified as the desired double-crossover mutants and named SB3026 (from pBS3068), SB3027 (pBS3069), and SB3028 (from pBS3070) mutant strains, whose genotypes as ACP6-1 (Ser3193Ala) and ACP6-2 (Ser3684Ala) single mutation and ACP6-1 (Ser3193Ala) and ACP6-2 (Ser3684Ala) double mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

In vitro Characterization of LnmG-catalyzed Loading of Malonyl CoA to LnmJ PKS ACP6-1 and ACP6-2

Overproduction and purification of LnmG, ACP6-1, ACP6-2, and Svp from E. coli have been reported previously.16,20 LnmG-catalyzed loading of malonyl CoA to ACP6-1 or ACP6-2 was carried out in a two-step procedures as previously described.16 Briefly, the apo-ACPs was first phosphopantetheinylated by Svp with CoA, and a typical reaction of 75 µL contained 100 mM Tris•HCl, pH 7.5, 12.5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM DTT, 33.3 µM CoA, 10 µM ACP, and 2 µM Svp. After incubation at 25°C for 60 min, a mixture of 2 µM LnmG and 133 µM malonyl CoA in a 15-µL volume was added. The resultant reaction mixture (90 µL) was incubated at 25 °C and subsequently quenched by addition of 900 µL of acetone at various time points. To prepare 14C-labeled samples for SDS-PAGE and subsequent phosphorimaging detection, [2-14C]malonyl CoA (51 mCi/mmol, Perkin-Elmer, Boston, MA) was added instead of cold malonyl CoA, and incubation was allowed to proceed for 5 min at 25 °C before quenching the reaction. Reaction workup and SDS-PAGE and phosphorimaging (LE phosphor screen, Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) of the resultant proteins were carried out on a 4–15% gradient gel as described previously.16 To prepare 14C-labeled samples for the semi-quantitative time-course assay, incubation of the same reaction mixture was allowed to proceed for 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, and 64 min at 25 °C before quenching. The terminated reactions were similarly worked up, and the labeled proteins were subjected to scintillation counting (Tri-Carb 2900TR liquid scintillation counter, Packard Instrument Co., Meriden, CT). The observed radioactivities (in DPM) for each reaction was normalized by subtracting the background radioactivity at the zero min time point. The relative radioactivity was calculated by setting the highest value-point as 100% (for ACP6-2, this value was observed at 2 min with 8856 DPM). To prepare samples for HPLC and ESIMS analysis, the reaction was scaled up three times with cold malonyl CoA as the substrate. Incubation was allowed to proceed for 10 min at 25 °C before quenching. HPLC and ESIMS analysis of the resultant proteins were carried out as described previously.16

Acknowledgment

We thank Kyowa Hakko Kogyo Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan, for the wild-type S. atroolivaceus S-140 strain, the Analytical Instrumentation Center of the School of Pharmacy, UW-Madison for support in obtaining MS data, and Drs. C. Richard Hutchinson and Steven G. Van Lanen for critical reading of the manuscript. This work is supported in part by University of California BioSTAR Program grant Bio99-10045 and Kosan Biosciences, Inc. (Hayward, CA) and NIH grants (CA106150 and CA113297). B.S. is the recipient of an NIH Independent Scientist Award (AI51689).

Footnotes

Dedicated to Dr. Norman R. Farnsworth of the University of Illinois at Chicago for his pioneering work on bioactive natural products.

References and Notes

- 1.Hopwood DA. Chem. Rev. 1997;97:2465–2497. doi: 10.1021/cr960034i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Staunton J, Weissman KJ. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2001;18:380–416. doi: 10.1039/a909079g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cane DE, Walsh CT, Khosla K. Science. 1998;282:63–68. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5386.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cane DE, Walsh CT. Chem. Biol. 1999;6:R319–R325. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)80001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDaniel R, Thamchaipenet A, Gustafsson C, Fu H, Betlach M, Ashley G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:1646–1851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xue Q, Ashley G, Hutchinson CR, Santi DV. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:11740–11745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Julien B, Shah S, Ziermann R, Goldman R, Katz L, Khosla C. Gene. 2000;249:153–160. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xue Y, Zhao L, Liu H-W, Sherman DH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:12111–12116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun Y, Zhou X, Dong H, Tu G, Wang M, Wang B, Deng Z. Chem. Biol. 2003;10:431–441. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(03)00092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu K, Chung L, Revill WP, Katz L, Reeves CD. Gene. 2000;251:81–90. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00171-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikeda H, Nonomiya T, Usami M, Ohta T, Omura S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:9509–9514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hara M, Asano K, Kawamoto I, Takiguchi T, Katsumata S, Takahashi K, Nakano H. J. Antibiot. 1989;42:1768–1774. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hara M, Takahashi I, Yoshida M, Asano K, Kawamoto I, Morimoto M, Nakano H. J. Antibiot. 1989;42:333–335. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakano H, Tamaoki T. In: Harnessing Biotechnology for the 21st Century, Proceedings of the 9th International Biotechnology Symposium and Exposition. Ladisch MR, Bose A, editors. Washington, D.C.: American Chemical Society; 1992. pp. 72–75. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng Y-Q, Tang G-L, Shen B. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:7013–7024. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.24.7013-7024.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng Y-Q, Tang G-L, Shen B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:3149–3154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0537286100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang G-L, Cheng Y-Q, Shen B. Chem. Biol. 2004;11:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu G-Y, Tam A, Lin L, Hixon J, Fritz CC, Powers R. Structure. 2001;9:277–287. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00586-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Findlow SC, Winsor C, Simpson TJ, Crosby J, Crump MP. Biochemistry. 2003;42:8423–8433. doi: 10.1021/bi0342259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sánchez C, Du L, Edwards DJ, Toney MD, Shen B. Chem. Biol. 2001;8:725–738. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas I, Martin CJ, Wilkinson CJ, Staunton J, Leadlay PF. Chem. Biol. 2002;9:781–787. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00164-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowe CJ, Böhm IU, Thomas IP, Wilkinson B, Rudd BAM, Foster G, Blackaby AP, Sidebottom PJ, Roddis Y, Buss AD, Staunton J, Leadlay PF. Chem. Biol. 2001;8:475–485. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xue Y, Sherman DH. Nature. 2000;403:571–575. doi: 10.1038/35000624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beck BJ, Yoon YJ, Reynolds KA, Sherman DH. Chem. Biol. 2002;9:575–583. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00146-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rahman AS, Hothersall J, Crosby J, Simpson TJ. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:6399–6408. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409814200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: a Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bierman M, Logan R, O’Brien K, Seno ET, Nagaraja R, Schoner BE. Gene. 1992;116:43–49. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90627-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kieser T, Bibb MJ, Buttner MJ, Chater KF, Hopwood DA. Practical Streptomyces Genetics. Norwich, UK: The John Innes Foundation; 2000. [Google Scholar]