Abstract

Tissue kallikrein KLK1 and the kallikrein-related peptidases KLK2–15 are a subfamily of serine proteases that have defined or proposed roles in a range of central nervous system (CNS) and non-CNS pathologies. To further understand their potential activity in multiple sclerosis (MS), serum levels of KLK1, 6, 7, 8 and 10 were determined in 35 MS patients and 62 controls by quantitative fluorometric ELISA. Serum levels were then correlated with Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) scores determined at the time of serological sampling or at last clinical follow-up. Serum levels of KLK1 and KLK6 were elevated in MS patients (p≤0.027), with highest levels associated with secondary progressive disease. Elevated KLK1 correlated with higher EDSS scores at the time of serum draw and KLK6 with future EDSS worsening in relapsing remitting patients (p≤0.007). Supporting the concept that KLK1 and KLK6 promote degenerative events associated with progressive MS, exposure of murine cortical neurons to either kallikrein promoted rapid neurite retraction and neuron loss. These novel findings suggest that KLK1 and KLK6 may serve as serological markers of progressive MS and contribute directly to the development of neurological disability by promoting axonal injury and neuron cell death.

Keywords: axon injury, kallikrein, prognosis, serine protease

Introduction

Despite progress in the development of treatments for relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), progressive forms remain a therapeutic challenge. Evidence suggests that the RR and progressive phases of disease may be caused by distinct mechanisms necessitating unique therapeutic approaches (Lassmann, 2007). Current MS therapies reduce relapses and new MRI lesions, but are less effective in attenuating progression. Further understanding the pathophysiology of progressive MS is therefore needed for the rational design of novel appropriate therapies.

Kallikreins (KLK) are emerging biomarkers in neoplastic and non-neoplastic conditions (Borgono and Diamandis, 2004), with KLK3 (prostate-specific antigen) being the most widely used serum marker for the diagnosis and prognosis of prostate cancer currently in clinical use. KLK1, KLK2 and KLK3 are highly homologous and were the first to be discovered. With sequencing of the human genome, an additional 12 kallikreins with less sequence homology were identified (Gan et al., 2000; Harvey et al., 2000; Yousef et al., 2000). Although tissue kallikrein proper (KLK1) and the remaining kallikrein-related peptidases (KLK2–15) (Lundwall et al., 2006) comprise the largest contiguous cluster of proteases in the genome, we are only beginning to understand their physiological roles and disease association. In relation to neurological disorders, altered KLK6 levels are found in both sera (Diamandis et al., 2000) and the central nervous system (CNS) in Alzheimer’s disease (Zarghooni et al., 2002), and within CNS ischemic (Uchida et al., 2004), and active MS lesions (Scarisbrick et al., 2002). With regard to MS, several kallikreins have been linked to immune cell activation (Scarisbrick et al., 2006) and targeting KLK6 (Blaber et al., 2004) or KLK8 (Terayama et al., 2005) attenuates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE).

Although immunopathogenic mechanisms of MS initiation and progression are incompletely understood, members of several protease families, termed the MS degradome, likely contribute. Proteolytic events participate in the development of inflammatory responses, including immune cell activation and extravasation, demyelination, cytokine, chemokine and complement activation, apoptosis, axon injury, and epitope spreading (Scarisbrick, 2008). Prior studies focused on serum or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of proteolytic enzymes have demonstrated altered levels in the case of both metalloproteases (Trojano et al., 1999; Waubant et al., 2003) and plasminogen activators (Cuzner et al., 1996; Akenami et al., 1997). For example, gelatinase B (matrix metalloprotease-9, MMP-9) levels are elevated in both sera and CSF of MS patients (Gijbels et al., 1992; Rosenberg et al., 1996). In sera, MMP-9 levels increase prior to an acute attack and the appearance of gadolinium-enhancing lesions (Trojano et al., 1999; Waubant et al., 1999). MMP-9 is thought to contribute to pathogenesis by promoting immune cell extravasation, activation of cytokines, and tissue destruction (Gearing et al., 1995; Chandler et al., 1996).

Given the abundance of kallikreins in serum (Shaw and Diamandis, 2007) and the potential utility of serum sampling to monitor MS disease activity, our goal in this study was to determine whether serum kallikrein levels are altered in MS patients. Furthermore, we determined whether serum kallikrein levels correlate with the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) as a measure of neurologic impairment, and/or the relapsing remitting (RR), or more progressive stages of disease. We focused these studies on five kallikreins, KLK1, KLK6, KLK7, KLK8 and KLK10, chosen for their known or proposed roles in inflammatory events (Bhoola et al., 2001; Scarisbrick et al., 2002; Blaber et al., 2004) and abundant expression in both immune organs and CNS (Scarisbrick et al., 2006). Results indicate that KLK1 and KLK6 may serve as serological markers of secondary progressive (SP) MS and in excess are likely to play a prominent role in neurodegeneration.

Results

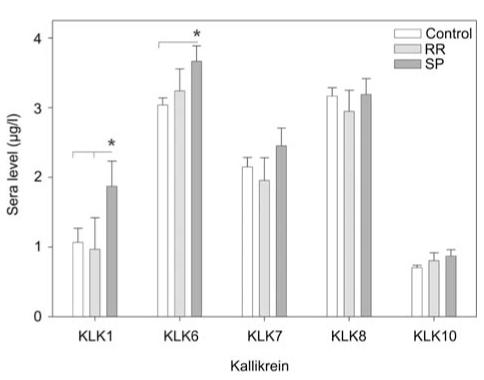

Kallikrein levels were determined in serum samples from 35 MS patients experiencing either an RR or SP disease course, and 62 healthy controls (Table 1). Serum levels of KLK1 (1.6±0.29 vs. 1.1±0.20 μg/l, p=0.03) and KLK6 (3.5±0.18 vs. 3.0±0.1 μg/l, p=0.01) were significantly elevated in MS patients relative to controls (Table 2). KLK1 levels were 46% greater and KLK6 levels 17% greater in the MS population relative to control samples. In controls, KLK6 serum levels were on average threefold higher relative to KLK1. Serum KLK8 was similar in abundance to KLK6, followed by KLK7 and KLK10, but these kallikreins did not differ between MS patients and controls. Although the mean age of control and MS cohorts was similar, the gender ratio differed (Table 1). However, there were no significant differences in KLK values between male and female control or MS subjects. As expected, there was a trend toward longer disease duration in the SP group (12.8±1.7 years, n=24) compared to RR patients (8.4±1.9 years, n=11), although this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.16). There was no correlation between serum KLK levels and disease duration when MS patients were examined as a whole. KLK levels were not significantly correlated with disease duration in the RR group, but in the SP group there was a small negative correlation in the case of KLK7 (R=-0.53 p=0.008) and KLK8 (R=-0.48, p=0.02).

Table 1.

Clinical features of patient samples.

| Controls | MS Patients | RR | SP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (M/F) | 62 (24/38) | 35 (10/25) | 11 (4/7) | 24 (6/18) |

| Mean (range) age (years) | 43.2 (22–61) | 42.4 (27–59) | 42.9 (27–51) | 42.8 (27–59) |

| Mean (range) disease duration (years) | - | 11.4 (1–28) | 8.4 (1–20) | 12.8 (1–28) |

| Median (range) EDSS | - | 6.0 (2–9.0) | 3.0 (2–6.5) | 6.5 (3.0–9) |

Demographic information for control and MS patients at the time of serological sampling. EDSS, Expanded Disability Status Scale; MS, multiple sclerosis; RR, relapsing remitting; SP, secondary progressive.

Table 2.

Mean kallikrein levels in serum of MS patients and controls.

| Controls | MS patients | RRMS | SPMS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KLK1 (μg/l) | 1.1±0.20 | 1.6±0.29 | 0.97±0.45 | 1.9±0.36 |

| KLK6 (μg/l) | 3.0±0.10 | 3.5±0.18 | 3.2±0.32 | 3.7±0.22 |

| KLK7 (μg/l) | 2.1±0.14 | 2.3±0.20 | 2.0±0.32 | 2.5±0.25 |

| KLK8 (μg/l) | 3.2±0.12 | 3.1±0.18 | 2.9±0.30 | 3.2±0.23 |

| KLK10 (μg/l) | 0.7±0.03 | 0.9±0.07 | 0.8±0.11 | 0.9±0.09 |

Kallikrein levels in serum of MS patients (n=35) and controls (n=62), and in MS patients with either a relapsing remitting (RRMS, n=11) or secondary progressive (SPMS, n=24) disease course (mean±SEM).

Comparison of KLK levels in serum from RR and SPMS patients showed a trend toward higher levels in the SP population (Figure 1). KLK1 was higher in SP patients (1.9±0.36 μg/l) than in both RR patients (0.97±0.45 μg/l), and controls (1.1±0.20, p<0.05) (p<0.008, ANOVA on ranks). KLK1 was elevated by 73% in SP patients relative to controls, and by 96% in SP patients relative to those with an RR disease course. Sera KLK1 levels in RR patients did not differ from controls. KLK6 levels were elevated by 23% in SP patients (3.7±0.22 μg/l) relative to controls (3.0±0.10, p=0.02), but no significant differences were found between RR (3.2±0.32 μg/l) and SP patients or controls.

Figure 1.

Serum kallikrein levels in RR and SPMS patients relative to controls.

Histogram shows the mean level of kallikrein in serum samples obtained from controls (n=62) or MS patients with a relapsing (RR) (n=11) or secondary progressive (SP) (n=24) disease course. Levels of KLK1 and KLK6 were significantly elevated in SPMS patients relative to controls. Higher KLK1 levels were also observed in SPMS patients relative to those with RR disease (Mann-Whitney U-test, p<0.05).

When MS serum samples were stratified according to EDSS at baseline, higher EDSS scores were associated with significantly higher levels of KLK1 in the MS population as a whole (R=0.45, p=0.007). To put this in some context, MS patients with serum KLK1 values below the median value of 0.72 μg/l (Table 3) had a median EDSS score of 4.5 (range 2–8) at baseline, whereas those with KLK1 levels above this median had a baseline EDSS score of 6.5 (range 2–9). Higher KLK6 serum levels at the time of blood draw correlated with higher EDSS at follow-up in the RR population (R=0.8, p=0.004). RR patients with KLK6 values below the median value of 3.4 μg/l at baseline had a median follow-up EDSS score of 5 (range 1.5–6.5), whereas those with KLK6 levels above the median serum level had a median follow-up EDSS score of 6.5 (range 5.5–8).

Table 3.

Median kallikrein levels in serum of MS patients and controls.

| Controls | MS patients | RRMS | SPMS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KLK1 (μg/l) | 0.4 (0.1–8.1) | 0.7 (0.04–6.4) | 0.3 (0.04–4.4) | 0.9 (0.2–6.4) |

| KLK6 (μg/l) | 3.1 (1.4–4.9) | 3.6 (1.4–5.3) | 3.4 (1.4–5.1) | 3.7 (1.6–5.3) |

| KLK7 (μg/l) | 1.9 (0.9–5.6) | 2.0 (1.0–6.1) | 1.6 (1.1–4.9) | 2.0 (1.0–6.1) |

| KLK8 (μg/l) | 3.1 (1.0–7.4) | 3.0 (1.6–7.3) | 3.0 (1.7–4.6) | 2.9 (1.6–7.3) |

| KLK10 (μg/l) | 0.7 (0.3–1.5) | 0.9 (0.3–2.1) | 0.9 (0.3–1.3) | 0.8 (0.3–2.1) |

Median (range) kallikrein levels detected in serum of MS patients (n=35) and controls (n=62). The MS population was further evaluated in terms of whether patients were experiencing a relapsing remitting (RRMS, n=11) or secondary progressive (SPMS, n=24) disease course at the time of blood draw.

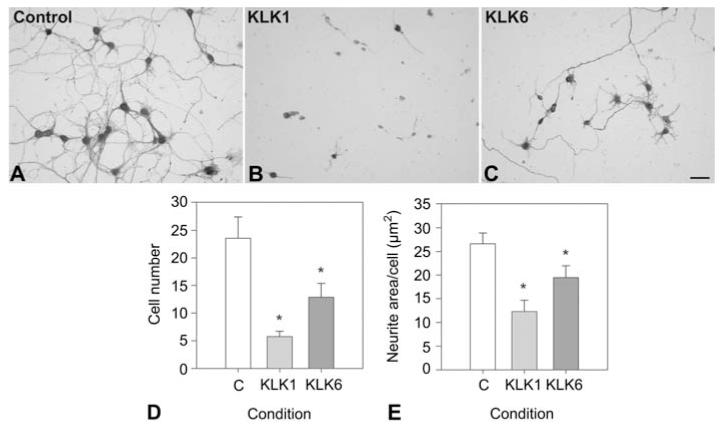

Since both KLK1 and KLK6 were associated with progressive MS, their effects on neuron integrity were determined in vitro (Figure 2). When applied to cortical neurons allowed to first mature in culture, both kallikreins promoted a rapid and significant decrease in neuron number and the number of associated neurites (ANOVA p=0.007, Student-Newman-Keuls p<0.05).

Figure 2.

KLK1 and KLK6 promote neurodegeneration.

In excess, recombinant KLK1 and KLK6 induce loss of both neurons and neurites. Murine cortical neurons grown on a charged surface for 96 h were exposed to 400 nM recombinant KLK1 (B) or KLK6 (C) for 24 h, or to vehicle alone (A), and stained for neurofilament protein. Cell number/field (D) was reduced by 76% by KLK1 (p=0.005), and 45% by KLK6 (Ps0.02) (mean and standard error per 20× field shown). Neurite area per cell (E) was reduced by 54% by KLK1 (p=0.006), and 27% by KLK6 (p=0.04). (*SNK p<0.05). The scale bar represents 100 μm.

Discussion

The most striking findings were the strong association between elevated KLK1 and KLK6 and SPMS, and the deleterious effects these kallikreins have on primary cortical neurons in culture. Perhaps related to these observations, positive correlations were observed between sera KLK1 and disability scores at the time of blood draw and that of KLK6 with future worsening. Taken together, these data suggest that KLK1 and KLK6 may represent important new therapeutic targets for the development of novel treatments for progressive MS patients.

Clinical differences between RR and SPMS are thought to relate to underlying pathophysiology. RR disease likely reflects CNS inflammation, with the formation of new focal white-matter lesions. Anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and immunosuppressive therapies reduce relapses and the formation of new gadolinium-enhancing lesions in RRMS (Polman et al., 2006). By contrast, similar therapies are less effective in progressive disease, in which new lesions are less frequent but atrophy of both white and gray matter is prominent. Although events related to neurodegeneration, such as microglial activation, gliosis, cytokine production, and axonal damage, characterize all phases of MS, these may be more profound and widespread in SPMS (Lassmann, 2007). Elevated serum KLK1 and KLK6 in SPMS and the profound loss of neurites and neurons observed with acute exposure to an excess of either kallikrein in culture may therefore relate to their participation in neurodegenerative activities that characterize the progressive phases of the disease.

The source of kallikrein in serum may include secretion by circulating inflammatory cells, since all five kallikreins examined are produced by spleen, thymus, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and bone marrow, and KLK6, KLK8, and KLK10 are upregulated by T-cell activation (Scarisbrick et al., 2006). KLK1 is present within leukocyte cytoplasmic granules and on the surface of neutrophils (Bhoola et al., 2001), and KLK8 is produced by murine mast cells (Wong et al., 2003). All five kallikreins are also expressed in CNS and found in CSF, such that leakage across a damaged blood-brain or blood-CSF barrier may additionally contribute to elevated serum levels. Both KLK1 and KLK6 are widespread in CNS, including expression in choroid plexus, cerebral cortex, thalamus, and brain stem (Raidoo et al., 1996; Scarisbrick et al., 1997, 2001; Mahabeer et al., 2000; Petraki et al., 2001). Notably, in ovarian cancer, the tumor itself does appear to be the source of elevated serum KLK6, since levels decrease following tumor resection (Diamandis et al., 2003).

Previous studies suggest that KLK6 drives inflammatory CNS pathogenesis, since this protease is strongly upregulated in activated immune cells (Scarisbrick et al., 2006), cleaves all major components of the blood-brain barrier, and readily degrades myelin proteins (Bernett et al., 2002; Scarisbrick et al., 2002). KLK6, previously termed neurosin (Yamashiro et al., 1997), zyme/protease M (Anisowicz et al., 1996), and myelencephalon specific protease (MSP) (Scarisbrick et al., 1997), is elevated within inflammatory demyelinating lesions in viral and autoimmune MS models, and in MS pathogenic lesions (Blaber et al., 2002, 2004; Scarisbrick et al., 2002; Christophi et al., 2004). Importantly, KLK6-function-blocking antibodies attenuate clinical and histological disease in EAE, an effect accompanied by reduced Th1 cellular responses (Blaber et al., 2004). The finding that higher serum KLK6 levels at baseline are correlated with future EDSS worsening in RRMS patients, taken with evidence of a role in neurotoxicity and oligodendrogliopathy (Scarisbrick et al., 2002), further supports the likely activity of KLK6 in neurodegenerative events driving MS disease progression.

Elevated serum KLK1 in SPMS patients and the correlation of this with concurrent disability suggest that KLK1, like KLK6, may play a role in disease progression. In vitro studies to date indicate that KLK1 can process a diverse array of peptide precursors, including prorenin (Sealey et al., 1978), insulin (Ole-MoiYoi et al., 1979), atrial natriuretic factor (Currie et al., 1984), and apolipoprotein B-100 (Cardin et al., 1984). Among the bestcharacterized properties of KLK1 is its ability to cleave low-molecular-weight kininogen to produce the potent vasodilator Lys-bradykinin (BK) (Bhoola et al., 2001). Kinins exert their effects on heterotrimeric G proteincoupled receptors, the constitutively expressed bradykinin2 (B2) receptor, and B1, which is upregulated during inflammation (Marceau et al., 1998). BK has been linked to promotion of inflammation (Araujo et al., 2001; Hellal et al., 2003), including potent induction of dendritic cell maturation that drives Th1 polarization via an IL-12-dependent pathway (Aliberti et al., 2003). However, in rodent models of ischemia, KLK1 gene transfer improves neurologic function, limits inflammation, suppresses oxidative stress, and enhances survival of neurons and glia in a B2-dependent manner (Xia et al., 2006). BK also upregulates the production of nerve growth factor in astrocytes (Noda et al., 2007). Despite potentially protective effects in some models of CNS injury, both the elevated serum levels associated with progressive MS and higher EDSS scores, and the neurite-damaging potential demonstrated in vitro point to a role for KLK1 in neurodegenerative events associated with MS disease progression.

Since KLK1 and KLK6 are secreted as proenzyme precursors, an important consideration is how they become activated in MS. Pro-KLK1 requires an arginine-specific protease and pro-KLK6 requires a lysine-specific protease for activation. Thus, there may be some ability of KLK6 to activate pro-KLK1, but it is unlikely that KLK1 cross-activates KLK6, or that either pro-KLK1 or pro-KLK6 is efficiently activated by an autolytic mechanism (Blaber et al., 2007; Yoon et al., 2007). In vitro studies have shown that plasmin and KLK5 are possible contenders as pro-KLK6 activators (Blaber et al., 2007), and KLK2 can activate pro-KLK1 (Yoon et al., 2007). Thus, the activation of pro-KLK1 and pro-KLK6 in MS may involve an extensive KLK cross-activation regulatory cascade, or an intersection with another protease family, such as the thrombolytic proteases that are also active in inflammatory processes.

These studies indicate that elevated serum KLK1 and KLK6 may serve as biomarkers of SPMS and that elevations in KLK6 in RR patients may be predictive of future worsening. Moreover, the neurotoxic properties demonstrated for both kallikreins provide a clear mechanism by which elevated levels may contribute to disease progression and disability. Further understanding the physiologic activities of these proteases across the CNS-immune axis, and their pathophysiologic roles in MS, will be critical to determining their potential as targets for novel therapies, perhaps especially in progressive disease.

Materials and methods

Patients

Serum samples from 35 MS patients were baseline draws from a clinical trial to determine the therapeutic effect of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) (Noseworthy et al., 2000). Control serum samples were from healthy volunteers without known MS or other neurological disease (n=62). MS patients had clinically definite or laboratory-supported MS and a baseline EDSS score between 2 and 9. MS patients were classified at the time of serological sampling as having a RR (n=11) or SP (n=24) disease course (Table 1). MS patients had irreversible motor deficit, persistent and stable for between 4 and 18 months at serological sampling, and had not received other therapy in the previous 3 months. Analysis of sera samples in this and the IVIg study were approved by the Mayo Institutional Review Board.

EDSS scores as a measure of neurological impairment were determined by an MS specialist at the time of enrollment into the IVIg study, and these values were used to determine correlation with serum KLK levels. Follow-up EDSS scores were determined by a trained physical therapist (RL) for all MS patients at the time of their most recent clinical visit by review of paper and electronic medical records without knowledge of KLK serological levels. To verify the reliability of follow-up EDSS, baseline scores were also determined retrospectively. Baseline EDSS scores determined at the time of blood draw and retrospectively produced nearly identical results, with a correlation coefficient of 0.93. Follow-up EDSS scores were obtained for 34 of 35 MS patients at a mean of 35±6 months after the initial blood draw.

Kallikrein quantification

Sensitive, sandwich-type, quantitative time-resolved fluorometric ELISAs were used to determine serum kallikrein levels as previously described (Diamandis et al., 2000, 2003). The assay for KLK1 is based on an affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibody. The assays for KLK6, 7, 8 and 10 are based on two mouse monoclonal antibodies, one used for capture and one for detection (biotinylated). The general assay procedure is as follows: microtiter wells were coated with the capture antibody at 500 ng in 100 μl/well overnight at room temperature in 50 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.5. The plate was then washed and 50 μl of standard or sample was added, along with 50 μl of assay buffer. The plates were incubated with shaking for 1 h at room temperature and washed four times. Then 100 μl of biotinylated detection antibody was added (approx. 5 ng/well) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. After washing the plates, 100 μl of streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase conjugate was added to the wells and incubated for 15 min. After additional washing, the alkaline phosphatase substrate, diflunisal phosphate, was added (10-3 M) and incubated for 10 min. Then 100 μl of developing solution (containing terbium chloride and EDTA) was added and incubated for 1 min. Fluorescence was then measured on a time-resolved fluorometer (CyberFluor 615 Immunoanalyzer, Nordion International, Kanata, Ontario, Canada). Data reduction was performed automatically. All assays are free from cross-reactivity toward other KLKs. The assays were sensitive down to 0.1 μg/l and the dynamic range was extended to 20 μg/l. All samples were analyzed in triplicate.

Primary neuron culture

Cortical neurons isolated from embryonic day-16 C57BL6/J mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were cultured on poly-L-ysine-coated cover slips in defined media (Lesuisse and Martin, 2002). After a 96-h period of maturation, neurons were exposed to an excess of recombinant KLK1 or KLK6 (400 nM) (Scarisbrick et al., 2002) or to vehicle alone for 24 h. Recombinant kallikreins were generated in our laboratory as previously described in detail (Bernett et al., 2002). Neurons were fixed, stained for neurofilament protein, and neurite length and neuron number were determined in four random fields per well using a program written for Axiovision (Zeiss, Thornwood, CA, USA). All experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated three times from independent cell culture experiments.

Data analysis

Mann-Whitney U-tests were used to compare KLK values between control and MS samples. Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance on ranks (ANOVA) with Dunn’s post hoc test was used to determine differences in KLK levels between controls and RR versus SP patients. The association of KLK levels with EDSS scores at baseline, or the most recent clinical follow-up, was evaluated by Spearman rank order correlation. Effects of KLK on cortical neurons were determined by ANOVA using the Student-Newman-Keul test. p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (RG 3367-B-4) and the Craig H. Neilsen Foundation to IAS and a Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service grant (1R15NS057771-01) to MB. The authors wish to thank Dr. Terry Therneau for input on the statistical analysis and the MS patients and other sera donors for their participation in this study.

References

- Akenami FO, Koskiniemi M, Farkkila M, Vaheri A. Cerebrospinal fluid plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in patients with neurological disease. J. Clin. Pathol. 1997;50:157–160. doi: 10.1136/jcp.50.2.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliberti J, Viola JP, Vieira-de-Abreu A, Bozza PT, Sher A, Scharfstein J. Cutting edge: bradykinin induces IL-12 production by dendritic cells: a danger signal that drives Th1 polarization. J. Immunol. 2003;170:5349–5353. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anisowicz A, Sotiropoulou G, Stenman G, Mok SC, Sager R. A novel protease homolog differentially expressed in breast and ovarian cancer. Mol. Med. 1996;2:624–636. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo RC, Kettritz R, Fichtner I, Paiva AC, Pesquero JB, Bader M. Altered neutrophil homeostasis in kinin B1 receptor-deficient mice. Biol. Chem. 2001;382:91–95. doi: 10.1515/BC.2001.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernett MJ, Blaber SI, Scarisbrick IA, Dhanarajan P, Thompson SM, Blaber M. Crystal structure and biochemical characterization of human kallikrein 6 reveals that a trypsin-like kallikrein is expressed in the central nervous system. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:24562–24570. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202392200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhoola K, Ramsaroop R, Plendl J, Cassim B, Dlamini Z, Naicker S. Kallikrein and kinin receptor expression in inflammation and cancer. Biol. Chem. 2001;382:77–89. doi: 10.1515/BC.2001.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaber SI, Scarisbrick IA, Bernett MJ, Dhanarajan P, Seavy MA, Jin Y, Schwartz MA, Rodriguez M, Blaber M. Enzymatic properties of rat myelencephalon-specific protease. Biochemistry. 2002;41:1165–1173. doi: 10.1021/bi015781a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaber SI, Ciric B, Christophi GP, Bernett MJ, Blaber M, Rodriguez M, Scarisbrick IA. Targeting kallikrein 6-proteolysis attenuates CNS inflammatory disease. FASEB J. 2004;19:920–922. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1212fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaber SI, Yoon H, Scarisbrick IA, Juliano MA, Blaber M. The autolytic regulation of human kallikrein-related peptidase 6. Biochemistry. 2007;46:5209–5217. doi: 10.1021/bi6025006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgono CA, Diamandis EP. The emerging roles of human tissue kallikreins in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2004;4:876–890. doi: 10.1038/nrc1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardin AD, Witt KR, Chao J, Margolius HS, Donaldson VH, Jackson RL. Degradation of apolipoprotein B-100 of human plasma low density lipoproteins by tissue and plasma kallikreins. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:8522–8528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler S, Cossins J, Lury J, Wells G. Macrophage metalloelastase degrades matrix and myelin proteins and processes a tumour necrosis factor-α fusion protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;228:421–429. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christophi GP, Isackson PJ, Blaber S, Blaber M, Rodriguez M, Scarisbrick IA. Distinct promoters regulate tissue-specific and differential expression of kallikrein 6 in CNS demyelinating disease. J. Neurochem. 2004;91:1439–1449. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie MG, Geller DM, Chao J, Margolius HS, Needleman P. Kallikrein activation of a high molecular weight atrial peptide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1984;120:461–466. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)91276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuzner ML, Gveric D, Strand C, Loughlin AJ, Paemen L, Opdenakker G, Newcombe J. The expression of tissue-type plasminogen activator, matrix metalloproteases and endogenous inhibitors in the central nervous system in multiple sclerosis: comparison of stages in lesion evolution. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1996;55:1194–1204. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199612000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamandis EP, Yousef GM, Petraki C, Soosaipillai AR. Human kallikrein 6 as a biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease. Clin. Biochem. 2000;33:663–667. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(00)00185-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamandis EP, Scorilas A, Fracchioli S, Van Gramberen M, De Bruijn H, Henrik A, Soosaipillai A, Grass L, Yousef GM, Stenman UH, et al. Human kallikrein 6 (hK6): a new potential serum biomarker for diagnosis and prognosis of ovarian carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003;21:1035–1043. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan L, Lee I, Smith R, Argonza-Barrett R, Lei H, McCuaig J, Moss P, Paeper B, Wang K. Sequencing and expression analysis of the serine protease gene cluster located in chromosome 19q13 region. Gene. 2000;257:119–130. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00382-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearing AJ, Beckett P, Christodoulou M, Churchill M, Clements JM, Crimmin M, Davidson AH, Drummond AH, Galloway WA, Gilbert R, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases and processing of pro-TNF-α. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1995;57:774–777. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.5.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gijbels K, Masure S, Carton H, Opdenakker G. Gelatinase in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with multiple sclerosis and other inflammatory neurological disorders. J. Neuroimmunol. 1992;41:29–34. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(92)90192-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey TJ, Hooper JD, Myers SA, Stephenson SA, Ashworth LK, Clements JA. Tissue-specific expression patterns and fine mapping of the human kallikrein (KLK) locus on proximal 19q13.4. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:37397–37406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004525200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellal F, Pruneau D, Palmier B, Faye P, Croci N, Plotkine M, Marchand-Verrecchia C. Detrimental role of bradykinin B2 receptor in a murine model of diffuse brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2003;20:841–851. doi: 10.1089/089771503322385773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassmann H. Multiple sclerosis: is there neurodegeneration independent from inflammation? J. Neurol. Sci. 2007;259:3–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesuisse C, Martin LJ. Long-term culture of mouse cortical neurons as a model for neuronal development, aging, and death. J. Neurobiol. 2002;51:9–23. doi: 10.1002/neu.10037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundwall A, Band V, Blaber M, Clements JA, Courty Y, Diamandis EP, Fritz H, Lilja H, Malm J, Maltais LJ, et al. A comprehensive nomenclature for serine proteases with homology to tissue kallikreins. Biol. Chem. 2006;387:637–641. doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahabeer R, Naidoo S, Raidoo DM. Detection of tissue kallikrein and kinin B1 and B2 receptor mRNAs in human brain by in situ RT-PCR. Metab. Brain Dis. 2000;15:325–335. doi: 10.1023/a:1011131510491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marceau F, Hess JF, Bachvarov DR. The B1 receptors for kinins. Pharmacol. Rev. 1998;50:357–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda M, Sasaki K, Ifuku M, Wada K. Multifunctional effects of bradykinin on glial cells in relation to potential anti-inflammatory effects. Neurochem. Int. 2007;51:185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noseworthy JH, O’Brien PC, Weinshenker BG, Weis JA, Petterson TM, Erickson BJ, Windebank AJ, Whisnant JP, Stolp-Smith KA, Harper CM, Jr, et al. IV immunoglobulin does not reverse established weakness in MS. Neurology. 2000;55:1135–1143. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.8.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ole-MoiYoi OK, Pinkus GS, Spragg J, Austen KF. Identification of human glandular kallikrein in the β cell of the pancreas. N. Engl. J. Med. 1979;300:1289–1294. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197906073002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petraki CD, Karavana VN, Skoufogiannia PT, Little SP, Howarth DJC, Yousef GM, Diamandis EP. The spectrum of human kallikrein 6 (Zyme/Protease M/Neurosin) expression in human tissues as assessed by immunohistochemistry. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2001;49:1431–1441. doi: 10.1177/002215540104901111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polman CH, O’Connor PW, Havrdova E, Hutchinson M, Kappos L, Miller DH, Phillips JT, Lublin FD, Giovannoni G, Wajgt A, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:899–910. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raidoo DM, Ramsaroop R, Naidoo S, Bhoola KD. Regional distribution of tissue kallikrein in the human brain. Immunopharmacology. 1996;32:39–47. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(96)00007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg GA, Dencoff JE, Correa N, Jr, Reiners M, Ford CC. Effect of steroids on CSF matrix metalloproteinases in multiple sclerosis: relation to blood-brain barrier injury. Neurology. 1996;46:1626–1632. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.6.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarisbrick IA. The multiple sclerosis degradome: enzymatic cascades in development and progression of central nervous system inflammatory disease. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2008;318:133–175. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-73677-6_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarisbrick IA, Towner MD, Isackson PJ. Nervous system specific expression of a novel serine protease: regulation in the adult rat spinal cord by excitotoxic injury. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:8156–8168. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08156.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarisbrick IA, Isackson PJ, Ciric B, Windebank AJ, Rodriguez M. MSP, a trypsin-like serine protease, is abundantly expressed in the human nervous system. J. Comp. Neurol. 2001;431:347–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarisbrick IA, Blaber SI, Lucchinetti CF, Genain CP, Blaber M, Rodriguez M. Activity of a newly identified serine protease in CNS demyelination. Brain. 2002;125:1283–1296. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarisbrick IA, Blaber SI, Tingling JT, Rodriguez M, Blaber M, Christophi GP. Potential scope of action of tissue kallikreins in CNS immune-mediated disease. J. Neuroimmunol. 2006;178:167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sealey JE, Atlas SA, Laragh JH, Oza NB, Ryan JW. Human urinary kallikrein converts inactive to active renin and is a possible physiological activator of renin. Nature. 1978;275:144–145. doi: 10.1038/275144a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw JL, Diamandis EP. Distribution of 15 human kallikreins in tissues and biological fluids. Clin. Chem. 2007;53:1423–1432. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.088104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terayama R, Bando Y, Yamada M, Yoshida S. Involvement of neuropsin in the pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Glia. 2005;52:108–118. doi: 10.1002/glia.20226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trojano M, Avolio C, Liuzzi GM, Ruggieri M, Defazio G, Liguori M, Santacroce MP, Paolicelli D, Giuliani F, Riccio P, Livrea P. Changes of serum ICAM-1 and MMP-9 induced by IFNβ-1b treatment in relapsing-remitting MS. Neurology. 1999;53:1402–1408. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.7.1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida A, Oka Y, Aoyama M, Suzukim S, Yokoi T, Katano H, Mase M, Tada T, Asai K, Yamada K. Expression of myelencephalon-specific protease in transient middle cerebral artery occlusion model of rat brain. Mol. Brain Res. 2004;126:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waubant E, Goodkin DE, Gee L, Bacchetti P, Sloan R, Stewart T, Andersson P-B, Stabler G, Miller K. Serum MMP-9 and TIMP-1 levels are related to MRI activity in relapsing multiple sclerosis. Am. Acad. Neurol. 1999;53:1397–1401. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.7.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waubant E, Goodkin D, Bostrom A, Bacchetti P, Hietpas J, Lindberg R, Leppert D. IFNβ lowers MMP-9/TIMP-1 ratio, which predicts new enhancing lesions in patients with SPMS. Neurology. 2003;60:52–57. doi: 10.1212/wnl.60.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong GW, Yang Y, Yasuda S, Li L, Stevens RL. Mouse mast cells express the tryptic protease neuropsin/Prss19. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;303:320–325. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00339-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia CF, Yin H, Yao YY, Borlongan CV, Chao L, Chao J. Kallikrein protects against ischemic stroke by inhibiting apoptosis and inflammation and promoting angiogenesis and neurogenesis. Hum. Gene Ther. 2006;17:206–219. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashiro K, Tsuruoka N, Kodama S, Tsujimoto M, Yamamura Y, Tanaka T, Nakazato H, Yamaguchi N. Molecular cloning of a novel trypsin-like serine protease (neurosin) preferentially expressed in brain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1997;1350:11–14. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(96)00187-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon H, Laxmikanthan G, Lee J, Blaber SI, Rodriguez A, Kogot JM, Scarisbrick IA, Blaber M. Activation profiles and regulatory cascades of the human kallikreinrelated peptidases. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:31852–31864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705190200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousef GM, Chang A, Scorilas A, Diamandis EP. Genomic organization of the human kallikrein gene family on chromosome 19q13.3–q13.4. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;276:125–133. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarghooni M, Soosaipillai A, Grass L, Scorilas A, Mirazimi N, Diamandis EP. Decreased concentration of human kallikrein 6 in brain extracts of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Clin. Biochem. 2002;35:225–231. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(02)00292-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]