Abstract

The tetracyclic core of anthracycline natural products with antitumor activity such as aclacinomycin A are tailored during biosynthesis by regioselective glycosylation. We report the first synthesis of TDP-L-rhodosamine and demonstrate that the glycosyltransferase AknS transfers L-rhodosamine to the aglycone to initiate construction of the side chain trisaccharide. The partner protein AknT accelerates AknS turnover rate for L-rhodosamine transfer by 200 fold. AknT does not affect the Km but rather affects the kcat. Using these data, we propose that AknT causes a conformational change in AknS that stabilizes the transition state and ultimately enhances transfer. When the subsequent glycosyltransferase AknK and its substrate TDP-L-fucose are also added to the aglycone, the disaccharide and low levels of a fully reconstituted trisaccharide form of aclacinomycin are observed.

Introduction

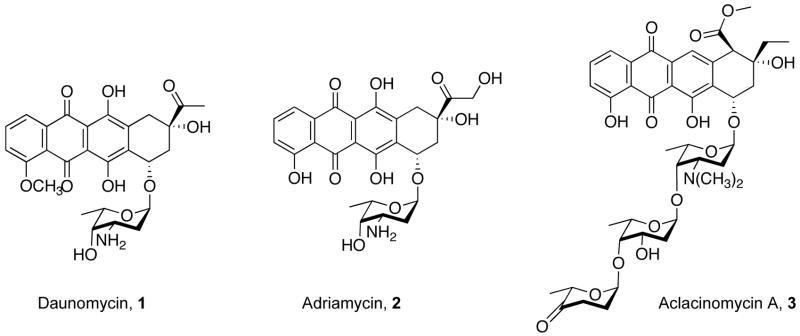

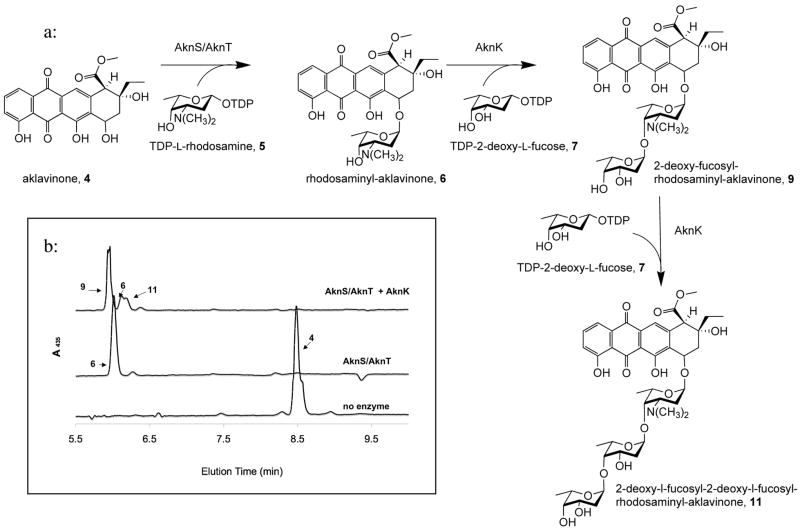

AknS is a glycosyltransferase (Gtf) that is involved in the biosynthesis of aclacinomycin A (1, Figure 1). Aclacinomycin A is a member of the anthracyclines, a class of microbial secondary metabolites produced by Streptomyces galilaeus with antitumor activity. Aclacinomycin A, along with other members of its class, including daunomycin (2) and adriamycin (3), is used in the clinic to treat various cancers.1 The mechanism of action of these chemotherapeutics is reported to be induction of apoptosis following binding to double stranded DNA fragments.2 All anthracyclines contain a conserved tetracyclic aglycone, 7,8,9,10-tetrahydro-5,12-napthacenequinone, with a mono to trisaccharide moiety attached to the C7-OH.3 The trisaccharide of aclacinomycin A, which consists of three different deoxy sugars, L-rhodosoamine, 2-deoxy-L-fucose, and L-cinerulose A, has been shown to play a key role in binding to the minor groove of target DNA sequences4–6. The trisaccharide is assembled by two glycosyltransferases, AknS, which attaches the first carbohydrate moiety, TDP-L-rhodosamine (4, Figure 2), to the aglycon (5) to yield rhodosaminyl-aklavinone (6). AknK, then sequentially attaches TDP-2-deoxy-L-fucose (7) and TDP-L-rhodinose (8), producing first 2-deoxy-fucosyl-rhodosaminyl-aklavinone (9) and then the trisaccharide, aclacinomycin A (3).7

Figure 1.

Anthracycline antitumor agents.

Figure 2.

Biosynthetic Pathway of Aclacinomycin A. a) Proposed biosynthetic patway: AknS/AknT transfers TDP-L-rhodosamine to aklavinone 4 to give rhodosaminyl-aklavinone 5. AknK then transfers TDP-2-deoxy-L-fucose followed by TDP-L-rhodinose which is then oxidized to yield Aclacinomycin A. b) HPLC analysis of AknS/T transfer of TDP- L-rhodosamine to aklavinone 4 to give rhodosaminylaklavinone 5.

The turnover of AknS is substantially increased by the addition of an accessory protein, AknT,8 which is encoded by a gene (aknT) found directly upstream of the aknS gene.9 A few other Gtfs involved in the biosynthesis of aminosugar-containing macrolides have also been found to require accessory proteins for good activity: DesVII, which is involved in the biosynthesis of narbomycin and EryCIII, which is involved in the biosynthesis of erythromycin.10, 11 How these accessory proteins accelerate glycosyltransfer is not known. The AknS/AknT system is ideal for addressing this issue because the aglycon substrate is chromogenic, which facilitates kinetic analysis of the glycosylation reaction. Here we report that AknT accelerates glycosyltransfer by increasing kcat by two orders of magnitude; it has no effect on substrate binding.8 We propose that AknT facilitates a conformational change in AknS that stabilizes the transition state.

Experimental

Materials

AknS, AknT, and AknK were over-expressed and purified as previously described.7, 8 TDP-daunosamine and TDP-2-deoxy-L-fucose were synthesized as previously reported.7, 12 The aglycone and psedoaglycone were obtained through degradation of aclacinomycin A.7, 8 Other chemicals were purchased from Sigma.

Synthesis of TDP-rhodosamine

TDP-L-rhodosamine (5) was synthesized from known TDP-L-daunosamine (10) (Figure 3).7, 12 A more detailed experimental procedure can be found in the supporting information of this paper.

Figure 3.

Synthesis of TDP-L-rhodosamime

Characterization of the glycosylation reaction catalyzed by AknS/AknT

Aklavinone (4) and TDP-L-rhodosamine (5) were incubated with AknT and AknS in 50 μL reaction buffer (75mM Tris [pH=7.5], 10mM MgCl2, and 10% [v/v] DMSO) at 25°C for 1–10 minutes unless otherwise noted. An aliquot (10 μL) of the reaction mixture was quenched with 90 μL of methanol. The sample was analyzed by RP-HPLC using a Pheomenex C18 column (30%–100% acetonitrile with 0.1% TFA in water over 8 minutes, 1 mL/min) (Figure 2). The products were monitored at 435 nm. The molecular weights of the products were confirmed by ESI-MS. The peak areas for the anthracycline monoglycoside products and the remaining aglycone substrate were integrated, and the product concentration was deduced from its percentage of the total area peak. The initial velocity data were fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation to obtain Km and kcat values.

To determine the kinetic parameters for AknS, 0.1 μM AknS and 0.3 μM AknT were included in each reaction. For the measurement of Km for TDP-L-rhodosamine, 0–1600 μM were used, while the aglycone was kept at 100 μM. For the measurement of the Km for the aklavinone, 1.5 μM – 200 μM aglycones were used, while TDP-rhodosamine was maintained at 1600 μM.

Characterization of the glycosylation reaction catalyzed by AknS

The same general buffer and the procedure for monitoring the reaction were used as described above. In order to determine the kinetic parameters of the reaction, 1 μM of AknS was used in each reaction. The AknS/T reaction was also tested at 1 μM of AknS/3 μM of AknT and we found the kinetic parameters to be comparable to the transfer using 0.1 μM of AknS/0.3 μM AknT. For the measurement of Km for TDP-L-rhodosamine, 0–1600 μM were used, while aglycone substrates were kept at 100 μM. For the measurement of the Km for the aklavinone, 1.5 μM – 200 μM aglycones were used, while the concentration of TDP-L-rhodosamine was maintained at 1600 μM.

Reconstitution of Aclacinomycin by tandem glycosylation with AknS/AknT and AknK

The reconstitution of aclacinomycin consisted of two steps. In the first step, 100 μM aklavinone (4) and 1600 μM TDP-L-rhodosamine were incubated with 9 μM AknS and 3 μM AknT in reaction buffer (75mM Tris [pH=7.5], 10mM MgCl2, and 10% [v/v] DMSO: 200 μL) at 25 degree C until HPLC analysis showed complete conversion to rhodosamine-aklavinone (6) (Figure 2 and Figure 4). 100 μL of this reaction mixture was incubated with 5 μM AknK and 1600 μM TDP-2-deoxy-L-fucose (7) for 6 hr to obtain 2-deoxyfucosyl-rhodosaminyl-aklavinone (8) and a small amount of 2-deoxyfucosyl-2-deoxyfucosyl-rhodsaminyl-aklavinone (11). To the other 100 μL of the reaction mixture, only AknK was added, no additional transfer was seen with this reaction (even after overnight incubation), indicating that AknK does not use TDP-rhodosamine as a substrate. The first mixture was analyzed by RP-HPLC using a C18 Phenomenex Column (30%-100% acetonitrile in 0.1% TFA in water over 8 min, 1 mL/min). The molecular weights of the desired products were confirmed by ESI-MS (for monoglycosylated calculated 569.6 found 570.1 [M+H]+, for diglycosylated calculated 699.7 found 701.2 [M+H]+, for triglycosylasted calculated 829.9 found 830.3 [M+H]+).

Figure 4.

AknS and AknK act in tandem to form a trisaccharide product. a) Biosynthetic Pathway of Aclacinomycin A. AknS/AknT transfers TDP-L-rhodosamine to aklavinone 4 to give rhodosaminylaklavinone 6. AknK transfers TDP-2-dexoy-L-fucose to yield the disaccharide product 9 and the trisaccharide product transfer 11. b) HPLC trace after the addition of each enzyme. The bottom trace shows aklavinone, the middle trace shows the conversion of aklavinone to 6 after addition of AknS/T and the top trace shows the conversion of 6 to 9 and 11 after addition of AknK.

Investigation of α-TDP-L-rhodosamine as substrate and/or inhibitor

The AknS/T reaction was performed as described above, but instead of incubating with β-TDP-L-rhodosamine, α-TDP-L-rhodosamine was used. No transfer was seen for the reaction. In order to evaluate the compound as an inhibitor of the reaction, 1600 μM β-TDP-L-rhodosamine was incubated with 100 μM aklavinone, 0.1 μM AknS and 0.3 μM AknT in the reaction buffer described above (20 μL total volume). α-TDP-L-rhodosamine was added to individual reactions in a range of concentrations from 0 to 20 mM. The reactions were monitored as described above.

Results

TDP-L-Rhodosamine is the natural substrate for Akns/AknT

Characterization of the AknS/AknT system was previously carried out using an alternate sugar donor, 2-deoxy-L-fucose presented as the TDP nucleotide.8 The turnover for the fucosylation reaction was very slow. In order to study the role of AknT in facilitating the glycosyltransfer reaction, we required the natural substrate, the identity of which was not known. We suggested in our previous work that AknS might add L-daunosamine from β–TDP-L-daunosamine, the product of which would later be methylated to produce rhodosamine.8 However, the catalytic efficiency of an α/β anomeric mixture of TDP-L-daunosamine was found to be poor, suggesting either that α-TDP-L-daunosamine inhibits the reaction or that β-TDP-L-daunosamine is not the natural donor. We began the studies reported here by evaluating the transfer of β-TDP-L-daunosamine purified from the α/β mixture. The enzyme couples the pure β -substrate at the same rate as the α/β mixture (0.05min−1), making it unlikely that TDP-L-daunosamine is the natural sugar donor substrate of AknS.

We next synthesized β–TDP-L-rhodosamine (5, Figure 3) by addition of formaldehyde to β-TDP-L-daunosamine (10, Figure 3) followed by hydrogenation. The product is unstable to HPLC purification and the final purification step was done using size exclusion chromatography under mild basic conditions (1% ammonium bicarbonate in H2O). The product was characterized by 1H, 31P NMR and by HRESI MS (data reported in the experimental section). Following purification, the β–TDP-L-rhodosamine can be stored both in water solution and as the dry ammonium salt at −20°C for a few months.

AknS/AknT transferred rhodosamine from β-TDP-L-rhodosamine to aglycone 4, as judged by a RP-HPLC assay and ESI-MS of the putative product ([M-H]+; calculated 569.3 found 569.3) (Figure 2). In previous work we had established that transfer of TDP-2-deoxy-L-fucose is most efficient using a ratio of 1:3 AknS:AknT.8 The optimal AknS:AknT ratio for transfer of TDP-rhodosamine was also 1:3. Under optimal conditions, kinetic parameters measured by monitoring product formation via RP-HPLC were found to be kcat = 9.6 min−1; Km(aglycone) = 5 μM; Km(TDP-rhodosamine) = 280 μM (Table 1). The kcat value is two orders of magnitude faster than for TDP-2-deoxy-L-fucose and three orders of magnitude faster than for TDP-L-daunosamine, supporting the proposal that TDP-L-rhodosamine is the natural substrate of AknS.

Table 1.

Kinetic analysis of AknS/AknT activity vs AknS activity

| Enzymes included in the reaction mixture | Km (μM) | kcat | |

|---|---|---|---|

| aklavinone | TDP-L-rhodosamine | ||

| AknS & AknT | 5.7 ± 0.8 | 280 ± 20 | 9.6 |

| AknS | 13.0 ± 3 | 349 ± 70 | 0.05 |

We next tested the ability of AknS to transfer TDP-L-rhodosamine to the aglycone 4 in the absence of AknT. The kcat for glycosyl transfer is 0.05 min−1 and the Km values for the aglycone and the TDP-rhodosamine substrates were 12.8 μM and 349 μM, respectively (Table 1). Thus, while there is no substantial change in substrate binding in the absence of AknT, there is a dramatic change in kcat. The presence of AknT accelerates turnover mediated by AknS by two orders of magnitude.

AknK does not transfer TDP-L-Rhodosamine

AknK is the next Gtf in the biosynthesis of aclacinomycin A and its natural substrate is TDP-2-deoxy-L-fucose. To probe the substrate selectivity of AknK, we incubated it with the pseudo-aglycone 6 and TDP-L-rhodosamine. No transfer was observed after 24 hours of incubation. Therefore, although AknS accepts TDP-2-deoxy-L-fucose as a slow substrate, AknK does not utilize TDP-L-rhodosamine.

Reconstitution of the biological pathway

AknS/T and AknK were used sequentially to synthesize 2-deoxy-fucosyl-rhodosamine-aklavinone from the aglycone and the corresponding TDP sugars. After incubating for 24 hours, two products were observed by LC-MS the disaccharide-aklavinone, 2-deoxy-fucosyl-rhodosaminyl-aklavinone 9 and the trisaccharide aklavinone, 2-deoxy-fucosyl-2-deoxy-fucosyl-rhodosaminyl-aklavinone 11 (Figure 5). Thus, the tandem transfer successfully produced the disaccharide product as the major product but minor amounts of the trisaccharide product were observed, consistent with previous observations that AknK can add 2-deoxy-L-fucose in two sequential reactions to yield a trisaccharide product.7

Discussion

Prior to this study AknS and AknT had been over-expressed and purified,8 but the glycosyltransfer reaction was not characterized with the natural substrate. Instead, β-TDP-2-deoxy-L-fucose and α/β-TDP-L-daunosamine were used as substrates because they were readily available. The AknS/AknT transferase activity was extremely low when TDP-2-deoxy-L-fucose was used (0.22 min−1) and even lower when α/β-TDP-L-daunosamine was used (0.01 min−1). Therefore, although we were able to show that AknT enhances the activity of AknS, the donor substrates were too poor to permit accurate kinetic measurements in the absence of AknT, which made it difficult to address the basis for the observed enhancement. In this paper, we have shown that β-TDP-L-rhodosamine is a highly active sugar donor for AknS, and the rates of the glycosyltransfer reaction in the presence and absence of AknT are sufficient to assess the kinetic basis for the observed enhancement.

Here we have reported that AknS/AknT transfers TDP-rhodosamine to the aglycone 4 with a kcat of 9.6 min−1, which is in the range of turnover numbers with other characterized Gtfs of this class (e.g., AknK and NovM).7, 13 The Km values were found to be 280 μM and 5.7μM for TDP-L-rhodosamine and aklavinone 4, respectively. In the absence of AknT, the Km for TDP-L-rhodosamine is 329 μM and the aklavinone Km is 12 μM, while the kcat is 0.05 min−1, which is two orders of magnitude slower than when AknT is present. These results reveal a negligible influence of AknT on AknS affinity for substrates, as judged by the similar Kms, but a dramatic influence of AknT on the catalytic rate constant for the reaction.

AknS is not the only glycosyltransferase that uses an accessory protein, as studies of two other homologous systems have been reported. For the EryCIII/EryCII system, it was observed that transient incubation of EryCII with EryCIII converts EryCIII from an inactive form to an enzyme that remains capable of catalyzing glycosyltransfer even after EryCII is removed. 10, 11 Preliminary experiments with the DesVII/DesVIII system have also shown that DesVIII is only required for initial activation of DesVII, and that the activated DesVII can catalyze the glycosyl transfer alone. 14 In contrast, significant AknS activity requires a three-fold excess of AknT during the glycosyl transfer reaction. It has been suggested that glycosyltransferase accessory proteins may function as substrate-carriers and as chaperones that facilitate the proper folding of their cognate Gtfs. The results reported here are not consistent with a substrate-carrier function for AknT and show instead that this protein markedly affects the turnover number. It is worth mentioning that there is one well-characterized example of a eukaryotic glycosyltransferase that functions with another protein. This Gtf, β1,4–Galactosytransferase-1 (β4-Gal-T1), interacts with α-lactalbumin(LA).15 The binding interaction stabilizes a particular conformation of Gal-T1 such that it accelerates the rate of transfer of sugars that are otherwise poor substrates.16 Detailed kinetic analysis of this system have revealed substantial changes (1000 fold) in the Km of Gal-T1 for glucose in the presence or absence of LA.17 Since we do not observe a change in the Km of AknS for either substrate, aklavinone or TDP-L-rhodosamine, in the presence of AknT, AknT may interact with AknS in such a way as to allow AknS to access a more favorable conformation in the transition state. AknS and AknT do not co-purify nor do they form a detectably stable complex so the acceleratory action must occur in a transient ternary complex of AknS, AknT and the two substrates.

Conclusion

We have reported the first synthesis of TDP-L-rhodosamime and have presented evidence that TDP-L-rhodosamine is the natural substrate for AknS during the biosynthesis of aclacinomycin. Tandem sugar transfer from TDP-L-rhodosamine followed by TDP-2-deoxy-L-fucose was accomplished using AknS/T and AknK, respectively. A small amount of trisaccharide product was observed, but the disaccharide product was the major product, consistent with the proposal that TDP-L-rhodinose rather than TDP-2-deoxy-L-fucose is the natural substrate for the third glycosyltransfer.9

Access to the natural L-sugar nucleotide substrate allowed us to probe the basis for AknS/T activation and our results have shown that AknT influences the catalytic rate constant for glycosytransfer but has no effect on Km values. The basis for this is under investigation.

Supplementary Material

Experimental procedures and spectral data for all compounds.This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH (Grant GM076710 to DK and SW) and (Grant GM49338 to CTW). CL was supported by a Bristol-Myers Squibb Graduate Fellowship in Synthetic Organic Chemistry.

References

- 1.Larsen AK, Escargueil AE, Skladanowski A. Pharmacol Ther. 2003;99:167–81. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(03)00058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rabbani A, Finn RM, Ausio J. Bioessays. 2005;27:50–6. doi: 10.1002/bies.20160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujii I, Ebizuka Y. Chem Rev. 1997;97:2511–2524. doi: 10.1021/cr960019d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaires J, Satyanarayana S, Suh D, Fokt I, Przewloka T, Priebe W. Biochemistry. 1996;35:2047–2053. doi: 10.1021/bi952812r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frederick C, Williams L, Ughetto G, van der Marel G, van Boom J, Rich A, Wang A. Biochemistry. 1990;29:2538–2549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Temperini C, Messori L, Orioli P, Di Bugno C, Animati F, Ughetto G. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:1464–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu W, Leimkuhler C, Oberthur M, Kahne D, Walsh CT. Biochemistry. 2004;43:4548–58. doi: 10.1021/bi035945i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu W, Leimkuhler C, Gatto GJ, Jr, Kruger RG, Oberthur M, Kahne D, Walsh CT. Chem Biol. 2005;12:527–34. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raty K, Kunnari T, Hakala J, Mantsala P, Ylihonko K. Mol Gen Genet. 2000;264:164–72. doi: 10.1007/s004380000306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan Y, Chung HS, Leimkuhler C, Walsh CT, Kahne D, Walker S. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:14128–9. doi: 10.1021/ja053704n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee HY, Chung HS, Hang C, Khosla C, Walsh CT, Kahne D, Walker S. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:9924–5. doi: 10.1021/ja048836f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oberthur M, Leimkuhler C, Kahne D. Organic Letters. 2004;6:2873–2876. doi: 10.1021/ol049187f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freel Meyers CL, Oberthur M, Anderson JW, Kahne D, Walsh CT. Biochemistry. 2003;42:4179–89. doi: 10.1021/bi0340088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borisova SA, Zhang C, Takahashi H, Zhang H, Wong AW, Thorson JS, Liu HW. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:2748–53. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brew K, Vanaman TC, Hill RL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1968;59:491–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.59.2.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramakrishnan B, Qasba PK. J Mol Biol. 2001;310:205–18. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klee WA, Klee CB. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1970;39:833–41. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(70)90398-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental procedures and spectral data for all compounds.This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.