Abstract

Hemorrhoidal bleeding is common during pregnancy. Other preexisting anorectal conditions can also be exacerbated by the increased vascular volume and pelvic congestion. We present the case of a young woman who developed life-threatening rectal bleeding requiring early delivery. Through use of endorectal endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), the condition was diagnosed as a diffuse cavernous rectal hemangioma. To our knowledge, this is the first report to present Doppler images of pulsatile flow through the cavernous hemangioma. The EUS findings are correlated with those of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imagining (MRI), and a brief discussion follows.

Introduction and Case Report

Introduction

Diffuse cavernous hemangiomas of the rectum are rare tumors, with approximately 120 cases described worldwide. This is the first report we have identified in which diagnostic endorectal Doppler ultrasonography images are presented. The case is also unique because early delivery was required secondary to the life-threatening severity of the bleeding. Familiarity with this condition and the use of selected imaging modalities can avoid a delay in diagnosis and avoid inappropriate treatments.

Case Report

The patient is a 29-year-old gravida 3, para 2, who presented at 35 weeks for cesarean section. The patient had had no problems with rectal bleeding during prior pregnancies, but in the second and third trimester of the current pregnancy she had severe recurring hemorrhage. She was seen by 2 gastroenterologists and a colorectal surgeon who identified oozing varicosities in the distal rectum. It was not felt that banding or surgical ligation would be helpful, but that presumably the congestion and bleeding would improve or resolve following delivery. She required 2 hospitalizations and received multiple transfusions; however, toward the final weeks of her pregnancy the bleeding increased to the point where she was losing 1 to 2 units of red blood cells per day. Rectal bleeding improved significantly immediately after delivery. CT of the abdomen and pelvis was ordered to rule out liver disease and portal venous pathology. Diffuse thickening of the rectum and distal sigmoid wall as well as multiple punctate calcifications were seen. The radiologist thought that an inflammatory process was the most probable cause (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

This coronal reformatting of abdominopelvic CT shows rectal wall thickening and clustered punctate calcifications. An inflammatory process was thought to be the most probable cause.

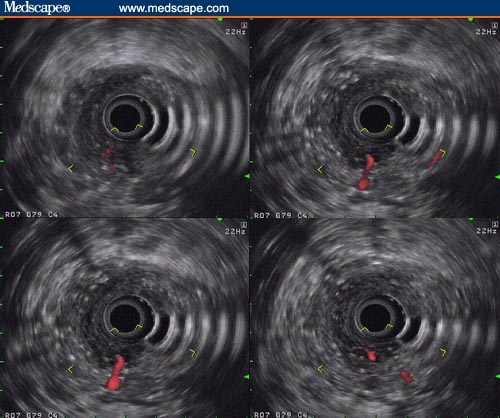

Based on the CT appearance and the clinical presentation, a differential diagnosis of diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the rectum was considered by one of us, and the patient was referred for anorectal endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) with the Doppler-equipped electronic radial echoendoscope (GF-UE 160, Olympus Co, Center Valley, PA). The following images show pulsatile arterial flow demonstrated by power-Doppler and a sponge-like mass with vascular channels surrounding the rectum (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Pulsatile flow into the rectal cavernous hemangioma with a large feeding vessel clearly visible close to the 6 o'clock position. The images were obtained with the GF-UE160 Doppler echoendoscope.

Figure 3.

This grayscale rectal ultrasonogram clearly shows the sponge-like nature of the cavernous hemangioma as it protrudes into the rectal lumen.

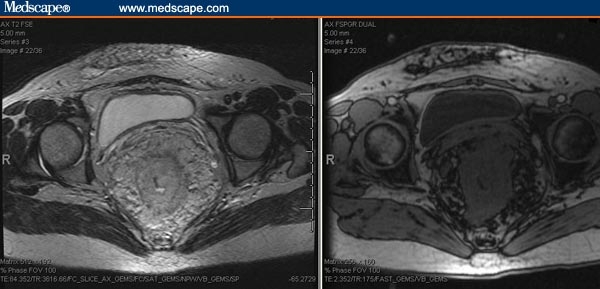

The classic findings of a diffuse rectal hemangioma were also seen on MRI (Figure 4) performed subsequently. The hemangioma extended through the internal sphincter to the level of the external sphincter. The patient is currently unsure whether she should pursue surgery because the bleeding has stopped.

Figure 4.

These are T2- (left) and T1-weighted (right) MRI images.

Characteristically, hemangiomas demonstrate bright signal intensity on T2-weighted images and intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images. Calcifications and blood vessels are signal-voided on both T1- and T2-weighted images, but thrombosed vessels have high signal intensity.

Discussion

Cavernous hemangiomas of the sigmoid colon and rectum are uncommon vascular malformations usually found in young adults with a long history of episodic and painless rectal bleeding. Alternatively, they may present with massive life-threatening hemorrhage. Histologically, colonic hemangiomas are easily separated from telangiectasias and angiodysplasias. They are usually considered benign hamartomas arising from the submucosal vascular plexus and are attributed to embryonic sequestration of mesodermal tissue.[1] However, large rectal cavernous hemangiomas can infiltrate the entire pelvis and behave aggressively.[2] Colonic hemangiomas are divided into capillary and cavernous types. The former tend to be small and asymptomatic, whereas the cavernous type, which is more frequently encountered, is either discrete and circumscribed or diffuse and expansive (Gentry Classification).[3] Large, tortuous vascular channels with turbulent, sluggish blood flow predispose to the formation of phleboliths.[1] In fact, the clustering of such phleboliths in an unusual location in a young individual with rectal bleeding is very suggestive of a cavernous hemangioma of the colon or rectum, although phleboliths are absent in half of the cases or difficult to see. Interestingly, our patient had CT for other reasons 2 years before the current presentation and no calcifications were seen. One could speculate that the repeated stop-and-go bleeding during pregnancy together with the repeated activation of local hemostatic mechanisms led to the rapid formation of these calcifications. Several authors have pointed out that the diagnosis is often missed for decades even with repeated colonoscopic examinations, and patients frequently are subjected to hemorrhoidectomies that are of no benefit. The diagnosis was much more quickly established in our patient since one of us (PC) was familiar with the entity. CT is useful for evaluation of rectal hemangiomas,[4] but if phleboliths are not present the diagnosis cannot be made with confidence or may be missed altogether. In our patient, the radiologist did not consider the possibility of cavernous hemangioma despite the presence of phleboliths. Characteristic MRI findings have been described[5] and consist of rectal wall thickening with high signal intensity on T2-weighted images and abnormal perirectal fat with serpiginous structures. Phleboliths are difficult to see on MRI. Most patients with recurrent rectal bleeding from cavernous rectal hemangiomas are young and otherwise healthy, and few physicians proceed rapidly to pelvic CT or MRI and particularly not during pregnancy. The evaluation of rectal bleeding is straightforward in the overwhelming majority of cases. In nonpregnant patients with severe, recurrent bleeding, a contrast CT of the abdomen and pelvis scan is obtained as a first step after a nondiagnostic colonoscopy. Even if the cause is not immediately clear, CT findings may still narrow the selection of further imaging studies, such as angiography – if a vascular fistula is suspected – or MRI – if a space-occupying lesion is found. If locally available, rectal endoscopic ultrasonography performed with a flexible Doppler-capable instrument, such as the GF-UE160,[6] may be the diagnostic instrument of choice because it avoids radiation or magnetic field exposure and cost run-ups for lesions that appear inflammatory or neoplastic. No sedation is required, and a Doppler-flow evaluation with high-resolution imaging is possible. In addition, biopsies can be obtained with transrectal ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration if needed. Moreover, rectal ultrasonography is conducted by gastroenterologists or colorectal surgeons familiar with rare rectal pathology. In patients with diffuse cavernous rectal hemangioma who consider or elect surgery, MRI may give the most information for surgical planning, allowing an individualized surgical approach with the goal of anal sphincter preservation.[1,7]

Many primary care physicians are not familiar with this rare entity, and it is worth pointing out that not all bright-red blood per rectum is related to benign hemorrhoids. In pregnancy, endorectal ultrasonography may be the imaging modality of choice in perplexing cases.

Footnotes

Reader Comments on: Massive Hemorrhage in Pregnancy Caused by a Diffuse Cavernous Hemangioma of the Rectum – EUS as Imaging Modality of Choice See reader comments on this article and provide your own.

Readers are encouraged to respond to the author at klausg@u.washington.edu or to Peter Yellowlees, MD, Deputy Editor of The Medscape Journal of Medicine, for the editor's eyes only or for possible publication as an actual Letter in the Medscape Journal via email: peter.yellowlees@ucdmc.ucdavis.edu

Contributor Information

Klaus Gottlieb, Endoscopic Ultrasound, Sacred Heart Medical Center, Spokane, Washington Author's email: klausg@u.washington.edu.

Philip Coff, Holy Family Hospital, Spokane, Washington.

Harold Preiksaitis, Sacred Heart Medical Center, Spokane, Washington.

Adam Juviler, Holy Family Hospital, Spokane, Washington.

Peter Fern, Sacred Heart Medical Center, Spokane, Washington.

References

- 1.Lyon D. Large-bowel hemangiomas. Dis Colon Rectum. 1984;27:404–414. doi: 10.1007/BF02553013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan T. Diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the rectum complicated by invasion of pelvic structures. Report of two cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1062–1066. doi: 10.1007/BF02237403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gentry RW. Vascular malformations and vascular tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Int Abstr Surg. 1949;88:281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsu R. Diffuse cavernous hemangiomatosis of the colon: findings on three-dimensional CT colonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1042–1044. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.4.1791042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Djouhri H. MR imaging of diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the rectosigmoid colon. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:413–417. doi: 10.2214/ajr.171.2.9694466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gottlieb K. Doppler-endosonography with the GF-UE 160 electronic radial echoendoscope - current use and future potential. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2007;16:455–461. Link to the abstract and full paper: http://www.jgld.ro/42007/42007_16.html. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham J. Diffuse cavernous rectal hemangioma–sphincter-sparing approach to therapy. Report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:344–347. doi: 10.1007/BF02553492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]