Abstract

Context

Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) face many challenges. One significant challenge is long-term adherence to disease-modifying therapy (DMT). Four of the 6 currently available DMTs involve self-injection, and all cause adverse events of varying degrees of severity. Although effective, the benefit of DMTs is difficult to determine on an immediate basis. Healthcare providers must play a major role in recognizing nonadherence and identifying strategies to promote adherence.

Evidence acquisition

We conducted a literature search of the MEDLINE database using the search terms “adherence” and “multiple sclerosis” to gather data from relevant studies investigating adherence among patients with MS.

Evidence synthesis

Barriers to maintaining treatment adherence in patients with MS include forgetting the medication, injection anxiety, perceived lack of efficacy, coping with adverse events, and issues with complacency and treatment fatigue. An open and honest healthcare provider-patient relationship is a core element in maintaining motivation and adherence in patients with MS. In addition, continuous education and consistent reinforcement of the value of treatment are essential strategies in the maintenance of treatment adherence. Other strategies to promote adherence include management of treatment expectations and minimization of adverse events.

Conclusions

The chronic nature of MS makes treatment adherence challenging in patients with long-standing disease. Patients and healthcare providers need to work together to establish open lines of communication and a trust-based therapeutic relationship to ensure that patients have the knowledge and skills they need to adhere to long-term MS therapy.

Introduction

A diagnosis of multiple sclerosis (MS) poses a variety of challenges. Patients and family members must cope with a chronic, potentially disabling disease for which there is no cure. Currently available disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) are all injectable. Coupled with the need to take additional symptomatic therapies, adherence to DMTs can be very difficult. Given these challenges, maintaining motivation and treatment adherence in patients with MS is important for optimal well-being. This article focuses on maintaining treatment adherence to DMTs in patients with long-standing MS by understanding reasons for declines in motivation and provides recommendations to optimize treatment adherence.

Defining Adherence

The term adherence comprises 3 distinct subcategories: acceptance, persistence, and compliance.[1] Before patients can adhere to a long-term medication regimen, they must first accept the necessity for it. In many cases, following diagnosis, patients with MS do not experience another relapse or significant signs or symptoms for months or years, which may make it difficult for them to accept that they need to routinely self-inject.[1] Once they have accepted the need for the regimen, patients must persist with the therapy. Persistence is frequently a casualty among MS patients, particularly within the first 6 months of therapy.[2] Compliance involves following the instructions on the prescription (ie, taking the medication at the right time, at the right dose, on the right day). Noncompliance is a common occurrence among patients with MS taking DMTs because they sometimes either forget a dose or deliberately withhold it.[1] In the Global Adherence Project, Devonshire and colleagues[3] found the most common reason for noncompliance among patients with MS was forgetting to inject (50%). Anecdotally, patients frequently cite other reasons for noncompliance, such as fatigue, needing a break, or adverse events. For the purposes of simplicity, this article will use the global term adherence, unless the information presented specifically relates to one of the subcategories.

Adherence Rates

Evaluations of interferon beta (IFN beta) and glatiramer acetate indicate that approximately 60% to 76% of patients with MS adhere to therapy for 2 to 5 years.[4–6] This compares with an adherence rate of 62% to 64% among patients taking insulin for type 2 diabetes[7] and 68% to 79% among patients taking oral medications for heart failure.[8]

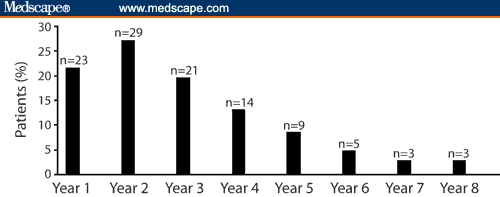

The majority of patients who discontinue therapy tend to do so within the first 2 years of initiating treatment. In a cohort of 107 of 632 patients who were observed for 8 years (mean, 47.1 months) and who discontinued treatment with IFN beta or glatiramer acetate, approximately 49% stopped treatment within the first 2 years (Figure 1).[9]

Figure 1.

Number and percentage of patients with MS discontinuing interferon beta or glatiramer acetate treatment each year over 8 years follow-up (n = 107). Reproduced from Rio J, Porcel J, Téllez N, et al. Factors related with treatment adherence to interferon beta and glatiramer acetate therapy in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005;11:306–309, by permission of Sage Publications Ltd.

Nonadherence to therapy can result in worse health outcomes.[10,11] One study showed that patients with relapsing-remitting MS who discontinued therapy had a significantly higher Kurtzke Expanded Disability Status Scale score at follow-up than patients who remained on treatment.[9] In addition, the proportion of patients who were relapse-free and progression-free was significantly lower among those who stopped therapy.[9]

Barriers to Adherence

Patients with MS face several barriers to adherence. Key among these are problems with injecting, perceived lack of efficacy, and adverse events.

Problems with injecting

One of the major barriers to adherence among patients with MS is that currently available therapies for relapsing-remitting MS require parenteral administration via self-injection or infusion. Common reactions when patients are asked to self-inject include fear, avoidance, anxiety, autonomic reactions, and disgust.[11] Some patients avoid self-injection by having family members administer the injection. Depending on another person to inject can be a barrier to adherence because it affects the independence of the patient and increases the likelihood of missed injections if the designated family member is not available.[11] In 1 study, of 12 patients who reported missing ≥ 1 injections, 10 relied on someone else to administer injections.[12] In the same study,[12] 13 of 101 patients who discontinued therapy at 6 months did so because they could not self-inject.

Reasons for problems with injecting go beyond simple needle phobia. Some patients believe that injections are dangerous. In their minds, this is confirmed if they experience an autonomic response (eg, flushing, palpitations) when injecting.[11] Other patients develop distorted beliefs about injections and believe that injections are a symbol of disease burden rather than optimal disease management.[11]

Perceived lack of efficacy

Some patients assume that their treatment is not working when current symptoms do not abate with regular DMT injections or they experience new symptoms. This perceived lack of efficacy can be the result of unrealistic treatment expectations.

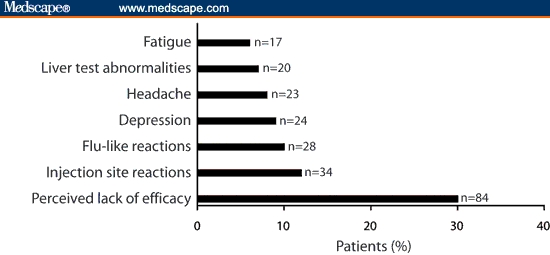

DMTs modify the immune response but cannot cure MS; thus, patients may continue to experience relapses, progression, and new brain lesions seen on the MRI. Unlike some injectable therapies, such as insulin, which enables a patient to measure its effectiveness by routinely checking blood glucose levels, no reliable and specific marker has been found to determine whether a therapy is working optimally for an individual MS patient. Studies show that perceived lack of efficacy accounts for 30% to 52% of discontinuations.[2,9] Tremlett and colleagues[2] reported that lack of efficacy was the most commonly reported reason for interruptions of therapy longer than 1 month in duration among patients receiving IFN beta therapy (Figure 2). Mohr and colleagues[13] found that before initiation of therapy, 57% of patients had unrealistically optimistic expectations of the ability of therapy to reduce relapses and 34% had similar expectations about the ability of therapy to improve functional status.

Figure 2.

Reasons for interrupted interferon therapy.[2]

Adverse events

Adverse events are another major reason for nonadherence to DMTs, with studies reporting that 14% to 51% of patients discontinue therapy for this reason.[5,6,10] In clinical trials of the IFN betas, the most common adverse events leading to clinical intervention (discontinuation, adjustment of dosage, or need for concomitant medication) included flu-like symptoms,[14–16] depression,[14–16] injection site reactions,[14,16] and elevated liver enzymes.[14,16] In a retrospective, hospital chart-based study of 394 MS patients treated for up to 8 years, the most common adverse events leading to discontinuation among IFN beta users were flu-like symptoms (23%), depression (21%), fatigue (16%), and injection-site reactions (16%).[5] In clinical trials of glatiramer acetate, the most common adverse events leading to clinical intervention included injection site reactions, vasodilation, tachycardia, tremor, and depression.[17] Approximately 10% of patients who inject glatiramer acetate complain of a systemic postinjection reaction characterized by flushing, tachycardia, and dyspnea.[17] Although this tends to resolve within minutes, it can be quite frightening when first experienced and influence a patient's willingness to adhere to therapy. There have been numerous cases of lipoatrophy associated with the use of glatiramer acetate reported in the literature.[18–20] In a study by Edgar and colleagues,[19] 34 of 76 patients who were or had been receiving glatiramer acetate developed lipoatrophy and 12 (35%) patients discontinued therapy. Lipoatrophy or other skin abnormalities was reported as a common reason for discontinuation. Development of lipoatrophy is disfiguring, often a permanent effect, and is associated with a significant psychological impact.[19] Thus, lipoatrophy may contribute to nonadherence.

Other barriers

Other potential barriers to adherence become apparent through discussions with patients. One of these barriers is complacency. In the early stages, DMT is frequently prescribed when a patient is in remission, making it more difficult for some patients to commit to self-injecting when they are feeling well. In addition, patients who have been on therapy for a while and have not experienced any relapses or signs of progression may begin to think that they do not need to self-inject any more or at least not as regularly as indicated or prescribed.[21]

Treatment fatigue can be a major problem among patients receiving long-term therapy. After several years of self-injecting, some patients simply get tired of the process and the restrictions MS therapy places on their lives. In addition, long-term DMT users may experience deterioration in their injection skills. In some cases, this is another form of complacency, but in others it may be related to subtle cognitive or functional deficits associated with MS. Cognitive deficits can interfere with a patient's memory, making it more likely that he or she will forget the injection or have difficulty executing the task. Problems with fine motor skills may impede some patients' ability to reconstitute their medication or administer injections. Depression and fatigue can also affect a patient's ability or willingness to self-inject. In other cases, family or support circumstances may change in such a way that patients may no longer have someone available to administer therapy. Equally important, a patient's financial circumstances or medical coverage may change such that he or she can no longer afford therapy.

Predictors of Adherence

Self-efficacy, self-esteem, hope, and disability have been reported as predictors of adherence.[22] Based on this, Fraser and colleagues[22] conducted an evaluation of adherence predictors in 341 RRMS patients receiving glatiramer acetate and found self-efficacy, hope, perceived healthcare provider support, and no previous use of DMTs to be significant predictors. In a separate evaluation of 199 patients with self-reported progressive forms of MS,[23] self-efficacy, perceived healthcare provider support, and spousal support were found to be significant predictors of adherence to glatiramer therapy. In a telephone survey of 89 veterans with long-standing MS (mean duration, 12 years) who were receiving a DMT (ie, IFN beta-1b, IFN beta-1a, or glatiramer acetate) for a mean of 3 years, perceived benefits of adherence independently predicted treatment adherence over a follow-up period of 6 months.[24]

Discussions with patients suggest that a major motivator for adherence is the fear of experiencing relapses and future disability. Other motivators include the desire to avoid burdening family members, seeing improvements on magnetic resonance images, rewarding oneself after injections, inspiring other MS patients, witnessing the consequences of not following medical advice in relatives with other diseases (eg, leg amputation in family member with diabetes), and taking control of MS therapy.

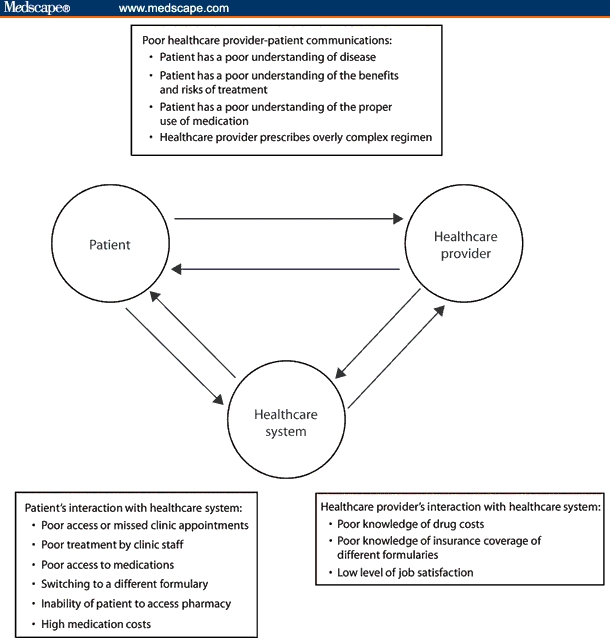

Importance of Healthcare Provider-Patient Relationship

The healthcare provider-patient relationship is often complex (Figure 3), and a poor relationship can contribute to treatment nonadherence.[25] For patients with a chronic neurologic disease such as MS, it is important to maintain an open and trusting healthcare provider-patient relationship. Both the patient and healthcare provider must understand what each expects of the other, to establish a satisfactory relationship.

Figure 3.

Interactions between patients, physicians, and healthcare system that can contribute to nonadherence. Reproduced from Osterberg L and Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487–497, by permission of Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Because we know that early diagnosis of MS is crucial for timely initiation of DMT, healthcare providers find themselves in a position of having to talk about MS as a possible diagnosis earlier in the diagnostic process than before. How healthcare providers present the diagnosis and treatment options and their willingness to listen to patients can dictate the future therapeutic relationship. Honesty and openness in the early stages enhances the relationship and establishes the basis for trust. How patients experience symptoms is individualized and subjective. Perceptions of symptom severity can vary markedly from patient to patient. These differences in perception can lead to communication breakdown.

Understanding of and empathy for a patient's fears, expectations, and health beliefs are critical. Patients need to feel that their healthcare providers understand the challenges that a diagnosis of MS presents: feelings of helplessness, changed family and work roles, and the difficulty associated with adhering to injectable therapies. Fraser and colleagues[23] found that perceived physician support is a significant predictor of adherence. In August 2007, a group of more than 99 MS Ambassadors (MS patients receiving subcutaneous IFN beta-1a who provide guidance and support to other MS patients through the educational support program, MS LifeLines) held a meeting. At this meeting, patients reported variability in the level of physician support. For example, some physicians leave the decision as to which DMT to initiate up to the patient. Although most patients wish to be involved in the decision, they do not necessarily want to be the sole decision-maker. Conversely, some patients reported that their physicians make treatment decisions for them without discussing available options. These patients have an understanding of the treatments and wish to be included in the decision-making process and participate as a partner in the treatment plan. The MS Ambassadors felt that information to help patients make an informed decision is lacking and that patients would be better able to participate in decision making with improved educational materials. The MS Ambassadors also reported that some healthcare providers ignore patients' complaints of adverse events, suggesting that in time patients will develop tolerance to these problems. On the other hand, many healthcare providers are aware that adverse events pose enormous challenges for treatment adherence and take steps to minimize the risk of adverse events and counsel patients on ways to avoid or overcome them.

A successful healthcare provider-patient relationship requires mutual respect, honesty, and openness. Such a relationship allows patients to benefit maximally from the healthcare provider's knowledge and skill and the healthcare provider will be more likely to respond appropriately to the patient's needs and expectations.

Strategies and Techniques to Maintain Treatment Adherence

Numerous strategies are available to help patients overcome barriers associated with adhering to DMTs (Table 1). Education about injection techniques and about what the patient can reasonably expect from therapy, and from MS itself, is a key strategy to successfully maintaining treatment adherence and should be an ongoing process. In addition, the value of the regimen and the importance of adherence need to be reinforced repeatedly.

Table 1.

Barriers to Adherence and Strategies to Overcome Them

| Barrier | Strategy |

|---|---|

| Unrealistic expectations |

|

| Injection/needle phobia |

|

| Adverse events |

|

| Complacency |

|

| Treatment fatigue |

|

| Cognitive deficits/deteriorating fine motor skills |

|

| Changed family circumstances |

|

| Changed financial circumstances |

|

Clues to nonadherence include missed appointments, missed refills, and evasiveness on the part of the patient. Patients should be asked about how they are coping with their treatment regimen in a specific, direct, and nonconfrontational manner. Asking if a patient is taking their DMT is not sufficient; rather patients should be asked specific questions such as “How many injections have you missed in the previous month?” If patients express difficulties with adherence, healthcare providers should make every effort to work with the patient to determine an acceptable solution. In some cases, the solution may involve seeking assistance from family members and/or friends. In other cases, reminder systems, such as drug diaries or alarms may be needed, especially for patients experiencing cognitive impairments. Regardless, several steps should be considered when determining the best way to maintain treatment adherence for an individual patient: set realistic expectations, address injection anxiety, and mitigate and cope with adverse events.

Setting Realistic Expectations

A simple starting point to promote adherence is educating patients about the necessity for therapy, while setting realistic expectations. Properly counselling patients before therapy is initiated can prevent problems with adherence down the road. For example, patients should be informed that although available agents reduce the incidence of relapses by approximately 30% to 50%, treatment also reduces the frequency and severity of relapses.[1] Although DMTs do not cure MS, through relapse reduction and delay in progression, they can help patients maintain function and quality of life. Moreover, patients who are in remission must understand that although they may not be experiencing relapses or signs of progression, the disease may be active at a subclinical level and thus, continuation of therapy is necessary to help reduce disease burden.

Dealing With Injection Anxiety

Patients who have problems with the concept of self-injecting may need intensive counselling to promote adherence. Once they are well taught, most patients will find the process easier than they thought and will have fewer problems with adherence.

For those who experience problems, the first step is to allay their fears about the safety of injections. This can be accomplished by educating them about proper medication preparation and injection technique.[11] For example, some patients may be concerned that the air bubble in the syringe will cause an air embolism, or that the injection itself will damage muscle or bones. In our experience, the presence of air bubbles can help make injections less uncomfortable because the air cleanses the needle before withdrawal, leaving less medication to irritate the tissue. Explaining this and emphasizing that these complications are highly unlikely, particularly if the injection is performed hygienically and with the proper technique, can help address these fears.

Other techniques to diminish injection anxiety include cognitive reframing, relaxation techniques, and minimizing adverse events. Cognitive reframing involves modifying one's thoughts to make them more accurate and useful.[11] For example, patients with MS are encouraged to view injections as a way of maintaining future health rather than as a further burden of their disease.[11] Autonomic responses associated with injection anxiety can be relieved through relaxation techniques such as deep muscle relaxation and breathing skills to prevent hyperventilation and other autonomic disturbances.[11]

Coping With Adverse Events

As is clear from earlier discussions, adverse events can be a major barrier to adherence.[5,6,10] Most adverse events associated with DMTs can be managed with appropriate injection techniques and lifestyle adjustments.[26]

Flu-like symptoms are associated with the use of IFN beta; these generally occur within 2 to 6 hours of injection and resolve within 24 hours. Patients should understand that their medication is not giving them the flu; rather they may experience symptoms similar to a flu-like illness. Informing patients of specific symptoms rather than using the term “flu-like symptoms” may help minimize concerns in some patients. Measures that help to reduce these symptoms include gradual titration of the prescribed agent from a low initial dose, and slowly escalating to the full dose. Concomitant use of an antipyretic or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications will help to reduce fever and achiness associated with flu-like symptoms. Nonpharmacologic measures include evening administration of injections, which allows patients to sleep through the flu-like symptoms, or scheduling injections (when possible) on days when the symptoms will be least disruptive.

A number of steps can be taken to attenuate or avoid injection site reactions and pain. Patients should be advised to routinely rotate injection sites, thoroughly wash hands and clean the injection site to avoid infection, allow medications to warm to room temperature, and cool the injection site with ice for 30 to 60 seconds before injecting to reduce swelling and pain. As an alternative, some patients find it helpful to apply heat rather than ice to the injection site before injecting. Painful intradermal injections can be avoided by ensuring complete needle penetration below skin's surface before injecting. Use of an autoinjector can help achieve appropriate needle depth. If necessary, local topical anesthetics (eg, lidocaine) can be used to prevent injection-site pain.[26]

The systemic postinjection reactions seen with glatiramer acetate are characterized by a combination of flushing, chest pain, palpitations, anxiety, dyspnea, throat constriction, and urticaria. Symptoms can last from 30 seconds to 30 minutes and may occur several months after initiation of therapy. These reactions tend to be self-limiting and usually do not require treatment. For cases in which these reactions persist and cause the patient to cut back on the injections or stop them altogether, the healthcare provider may consider changing therapy. When initiating therapy with glatiramer acetate, patients must be told about the risk of systemic reactions, which are temporary and not considered harmful.

Conclusions

MS is a complex disease that is currently managed by parenterally administered disease-modifying drugs. Patient adherence to injectable MS therapies is an issue that needs to be addressed from the time of diagnosis throughout the disease course.

A wide range of factors influence a patient's ability to adhere to therapy. Access to and communication with healthcare providers are key elements in the promotion of adherence. Establishing an open and honest healthcare provider-patient relationship; setting realistic expectations about therapy; and providing ongoing education about MS, injection technique, and adverse event management are responsibilities that both the healthcare provider and patient must embrace. Optimizing motivation and adherence in patients with long-standing MS will allow these patients to realize the benefits of DMTs, while awaiting the advent of a new generation of therapies that may offer even greater hope.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge EMD Serono, Inc., Rockland, Massachusetts, and Pfizer Inc, New York, NY, for supporting the development of the manuscript. All authors had significant input to the content of and revisions to the manuscript. The authors wish to acknowledge Jo Stratmoen, RN, BSN, and Maryann Travaglini, PharmD, for editorial assistance with the manuscript.

Footnotes

Reader Comments on: Recognizing Nonadherence in Patients With Multiple Sclerosis and Maintaining Treatment Adherence in the Long Term See reader comments on this article and provide your own.

Readers are encouraged to respond to the author at kcostello@som.maryland.edu or to Peter Yellowlees, MD, Deputy Editor of The Medscape Journal of Medicine, for the editor's eyes only or for possible publication as an actual Letter in the Medscape Journal via email: peter.yellowlees@ucdmc.ucdavis.edu

Contributor Information

Kathleen Costello, Maryland Center for Multiple Sclerosis, University of Maryland, Baltimore, Maryland Author's email: kcostello@som.maryland.edu.

Patricia Kennedy, The Heuga Center and Rocky Mountain MS Center, Englewood, Colorado.

Jo Scanzillo, Nursing Support, MS LifeLines, US Neurology, EMD Serono, Inc., Rockland, Massachusetts.

References

- 1.Devonshire V. Adherence to Disease-Modifying Therapy: Recognizing the Barriers and Offering Solutions. Ridgewood, NJ: Delaware Media Group, LLC; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tremlett HL. Interrupted therapy: stopping and switching of the beta-interferons prescribed for MS. Neurology. 2003;61:551–554. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000078885.05053.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Devonshire V, et al. The Global Adherence Project (GAP)–A multicenter observational study on adherence to disease-modifying therapies in patients suffering from relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Presented at the 22nd Congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis; September 27–30, 2006; Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haas J. Twenty-four-month comparison of immunomodulatory treatments - a retrospective open label study in 308 RRMS patients treated with beta interferons or glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) Eur J Neurol. 2005;12:425–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2005.00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Rourke KE. Stopping beta-interferon therapy in multiple sclerosis: an analysis of stopping patterns. Mult Scler. 2005;11:46–50. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1131oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruggieri RM, et al. Long-term interferon-beta treatment for multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci. 2003;24:361–364. doi: 10.1007/s10072-003-0190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cramer JA. A systematic review of adherence with medications for diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1218–1224. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray MD, et al. Pharmacist intervention to improve medication adherence in heart failure: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:714–725. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-10-200705150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rio J, et al. Factors related with treatment adherence to interferon beta and glatiramer acetate therapy in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005;11:306–309. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1173oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clerico M. Adherence to interferon-beta treatment and results of therapy switching. J Neurol Sci. 2007;259:104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.05.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox D. Managing self-injection difficulties in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2006;38:167–171. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200606000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohr DC. Injectable medication for the treatment of multiple sclerosis: the influence of self-efficacy expectations and injection anxiety on adherence and ability to self-inject. Ann Behav Med. 2001;23:125–132. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2302_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohr DC, et al. Therapeutic expectations of patients with multiple sclerosis upon initiating interferon beta-1b: relationship to adherence to treatment. Mult Scler. 1996;2:222–226. doi: 10.1177/135245859600200502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rebif [R] [package insert] Rockland, Massachusetts, and New York, NY: EMD Serono, Inc., and Pfizer Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avonex [R] [package insert] Cambridge, Massachusetts: Biogen Idec Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Betaseron [R] [package insert] Wayne, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Copaxone [R] [package insert] Kfar-Saba, Israel: Teva Pharmaceuticals Industries, LTD; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drago F. Localized lipoatrophy after glatiramer acetate injection in patients with remitting-relapsing multiple sclerosis. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1277–1278. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.10.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edgar CM. Lipoatrophy in patients with multiple sclerosis on glatiramer acetate. Can J Neurol Sci. 2004;31:58–63. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100002845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soos N. Localized panniculitis and subsequent lipoatrophy with subcutaneous glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) injection for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:357–359. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200405050-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen BA. Adherence to disease-modifying therapy for multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2006;(February Supplement):32–37. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fraser C. Predictors of adherence to Copaxone therapy in individuals with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2001;33:231–239. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200110000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fraser C. Predictors of adherence to glatiramer acetate therapy in individuals with self-reported progressive forms of multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2003;35:163–170. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200306000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turner AP. Predicting ongoing adherence to disease modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis: utility of the health beliefs model. Mult Scler. 2007;13:1146–1152. doi: 10.1177/1352458507078911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Osterberg L. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langer-Gould A. Strategies for managing the side effects of treatments for multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2004;63:S35–41. doi: 10.1212/wnl.63.11_suppl_5.s35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]