Abstract

Estrogen receptors are historically perceived as nuclear ligand activated transcription factors. An estrogen receptor has now been found localized to the plasma membrane of human myeloblastic leukemia cells (HL-60). Its expression occurs throughout the cell cycle, progressively increasing as cells mature from G1 to S to G2/M. To ascertain that the receptor functioned, the effect of ligands, including a non-internalizable estradiol-BSA conjugate and tamoxifen, an antagonist of nuclear estrogen receptor function, were tested. The ligands caused activation of the ERK MAPK pathway. They also modulated the effect of retinoic acid, an inducer of MAPK dependent terminal differentiation along the myeloid lineage in these cells. In particular the ligands inhibited retinoic acid-induced inducible oxidative metabolism, a functional marker of terminal myeloid cell differentiation. To a lesser degree they also diminished retinoic acid-induced earlier markers of cell differentiation, namely CD38 and CD11b. However, they did not regulate retinoic acid-induced G0 cell cycle arrest. There is thus a membrane localized estrogen receptor in HL-60 myeloblastic leukemia cells that can cause ERK activation and modulates the response of these cells to retinoic acid, indicating cross-talk between the membrane estrogen and retinoic acid evoked pathways relevant to propulsion of cell differentiation.

INTRODUCTION

Estrogen is an agonist for the nuclear ligand activated transcription factor, estrogen receptor. The estrogen receptors (ER) belong to the steroid-thyroid hormone super family of nuclear receptors. However, it has long been known that there are also membrane localized estrogen receptors [1]. Recognition of non-nuclear ER effects in mammalian cells is still emerging, and different aspects have been reported in a variety of cells [2–5]. However, a notable exception is hematopoietic cells. For example, evidence of a membrane estrogen receptor (mER) has more recently been discovered in cells from estrogen responsive tissue. In particular, MCF-7 breast carcinoma cells express mER that can cause rapid MAPK signaling [6, 7]. In another instance, namely neuronal cells, mER can also cause signaling, activating PKC and PKA to activate inwardly rectifying K+ channels [8]. Furthermore mER, in particular of the form ERα have been observed to dimerize in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC), and dimerization is a frequent feature of membrane receptor signaling. In this case MAPK signaling was elicited. In addition to MAPK, PI3-K and also PKC pathways have been suggested in mER signaling [9]. In another study of MCF-7 cells, the mERα has been found to complex with the IGF receptor and mediate its signaling [10, 11]. Crosstalk between mER and other membrane growth factor receptors thus exists, and mER driven MAPK, PI3-K and PKC pathways have been implicated in the crosstalk [12, 13]. There is thus a precedent for a mER that signals in mammalian cells in addition to the historically dominant paradigm of a nuclear steroid receptor for estrogen. Three potential mER candidates have in fact been indicated in different cellular scenarios, ERα, ERβ, and GPR30 (G-protein coupled) [3–5]. There is thus motivation for ascertaining mER expression and its potential functions. Given its reported occurrence in different physiological contexts, interest in a potential role of mER in regulating cell proliferation and differentiation might be anticipated.

Retinoic acid (RA) is a ligand for RAR, another member of the steroid thyroid hormone super family, and its isomerization product, 9-cis-RA, is also a RXR ligand. RA is a developmental morphogen that regulates cell differentiation and cell cycle arrest in G0. In HL-60 myeloblastic leukemia cells, RA is known to cause the expression of several cell surface receptors that signal through the RAF/MEK/ERK axis of MAPK signaling to cause up-regulation of a series of progressively appearing cell differentiation markers culminating in terminal cell differentiation associated with p21 CDKI up-regulation, inhibition of cyclin D1 and cell cycle arrest [14]. Significantly, the MAPK signal is not the transient signal characteristic of mitogenic MAPK signaling, but is a durable protracted signal which must be sustained to elicit differentiation. In HL-60 cells estradiol at low doses stimulated proliferation but at high doses inhibited proliferation, an effect curiously similar to that known for retinoic acid [15]. Crosstalk between RA and ER has also been demonstrated at the nuclear level, where for instance overlapping RARE and ERE occur as for the lactoferrin gene [16]. However, the involvement of MAPK signaling for both estrogen and retinoic acid, as well as the curious dose-dependent effects of estrogen and the existence of membrane ERs, suggests the possibility of non-nuclear cross-talk. In particular if it exists, a mER in HL-60 cells may signal through the MAPK pathway and affect RA-induced signaling and downstream effects on cell differentiation. Such an occurrence would indicate a novel function of estrogen in regulating the effects of RA.

The present report shows that a membrane bound estrogen receptor exists in HL-60 human myeloblastic cells and that its occurrence is of functional significance in eliciting ERK activation and regulating the cellular differentiation induced by RA. The expression of membrane localized ER occurred in G1, S and G2 cells at progressively increasing levels as cells progressed through the cell cycle. It was slowly down regulated by RA without apparent cell cycle specificity. A non-internalizable estradiol conjugated to BSA stimulated ERK activation and modulated the effects of RA, inhibiting the occurrence of late stage functional differentiation, but to a much lesser degree earlier stages of RA-induced differentiation. In contrast RA-induced G0 arrest was not affected, suggesting that the membrane ER signal affected RA-induced phenotypic conversion, but not cell cycle arrest. Interestingly, tamoxifen, an ER ligand and antagonist for its nuclear/transcriptional effects, had similar effects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and Culture Conditions

HL-60 human leukemia cells were grown in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 5% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum in a humidified incubator of 5% CO2, as previously described [14, 17]. Cell cultures were re-cultured at a density of 0.2 million cells/ml for 48 hours of growth or 0.1 million cells/ml for 72 hours of growth. Both were grown to 1 million cells/ml. Cultures were maintained in a state of continual exponential growth at a volume of 10 ml in a T25 flask or 30 ml in a T75 flask.

Experimental cell cultures were created by passing exponentially growing cells at a density of 0.2 million cells/ml. At the time of reculturing, the medium was supplemented with 320 µl of β-Estradiol 6-(O-carboxymethyl)oxime: BSA (E2-BSA) diluted to 7.19 ×10−7 M of Estradiol in sterile PBS or 7.5 µl Tamoxifen at 10 mM in ethanol. Cell with estradiol, Tamoxifen, and a control group treated with vehicle only were set up both with and without 2 µl of 5 × 10−3 M Retinoic Acid in ethanol into 10 ml of cell culture. These amounts produced final concentrations of 1 µM RA, 0.23 µM Estradiol and .75 µM Tamoxifen. All reagents were obtained from Sigma® (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated.

Quantification of Membrane Estrogen Receptors

β-Estradiol 6-(O-carboxymethyl)oxime: BSA fluorescein isothicyanate conjugate (3–5 mol FITC/mol BSA, 5–10 mol steroid/mol BSA) and BSA fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugate (Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, MO) were both diluted to 10−6 M of BSA in PBS. To ensure consistent dosing only one batch of stock was used for all treatment groups. BSA-FITC was used as the control for the nonspecific FITC signal whereas E2-BSA-FITC measured the specific mER signal. FITC or E2-FITC had the potential of being transported across the cell membrane and reporting nuclear or cytoplasmic estrogen receptors as well as the desired membrane receptors. Thus, a BSA-bound conjugate was used so that its large size (70 kDa) would prevent the internalization of the fluorescent molecule. Post-treatment cells were harvested at several time points in samples of half a million cells and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 minutes (standard harvesting protocol). Samples were then incubated in 500 ìl of either BSA-FITC or E2-BSA-FITC at 37°C for 40 minutes. The cells were then fixed with 62.5 µl of 16% stock solution of paraformaldehyde (from Alpha Aesar, Ward Hill, MA) to a final concentration of 2% and allowed to incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes. After storage at 4°C the samples were washed in PBS before relative FITC fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry (LSRII, Becton Dickinson, Mountainview, CA). The bound FITC molecules were excited by a 488 nm laser and emission was collected through a 505 long pass dichroic mirror and a 530/30 nm band pass filter.

In order to asses the nuclear translocation of ERα upon unconjugated estradiol administration, the nuclei were isolated with a citrate hypotonic solution as previously described [14, 17] followed by lysis of the nuclei with RIPA buffer, centrifugation for 20 minutes at 12000g, and Western bloting using a rabbit ERα antibody kindly provided by Dr W Lee Kraus, Cornell University.

Quantification of Differentiation by DCF

Functional differentiation measured by the occurrence of inducible oxidative metabolism was assayed by flow cytometry as previously described [14, 17]. 5-(and-6)-chloromethyl-2’,7’-dichlorodihydro-fluorescein diacetate, acetyl ester (CM-H2DCFDA) from Invitrogen® (Carlsbad, CA) was suspended in DMSO at 2.9 µg/µl. When combined with TPA (12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate) in DMSO, each used with a treatment of 1 µl/ml PBS for a final concentration of 5 µM DCF and 0.2 µg/ml TPA, the DCF measures the reactive oxygen species (ROS) induced by TPA as an indicator of inducible cellular ROS expression and thus of differentiation. Standard harvesting protocol was followed with all treatments at 48 hours and then samples were incubated in 200 µl of the PBS + DCF + TPA mixture for 20 minutes. The relative fluorescence resulting from the oxidized DCF was measured immediately by flow cytometry in the same manner as in the above protocol using 488 nm excitation with emission collected through a 505 nm long pass dichroic mirror and a 530/30 nm band pass filter masking the photomultiplier.

Quantification of Differentiation by CD11b and CD38 Markers

Expression of cell surface differentiation markers was measured by flow cytometry as previously described [14, 17, 18]. Antibodies against CD11b/Mac-1 and CD38 cell surface differentiation markers were obtained from BD Pharmingen and added separately to half a million treated cells at a concentration of 5 µl/ml. The anti-CD11b and anti-CD38 antibodies are APC-conjugated and PE-conjugated respectively.

APC fluorescence is excited at 633 nm and collected with a 660/20 band pass filter. PE fluorescence is excited at 488 nm and collected with a 576/26 band pass filter. Standard harvesting protocol was followed and then the samples were incubated in the anti- CD11b stain for 1 hour and the anti-CD38 stain for 45 minutes, both at 37°C. Samples were harvested at 48 hours for CD11b live-staining and at 12 hours for CD38 live-staining.

Quantification of ERK

ERK activation was measured by flow cytometry as previously described [14, 17]. The flow cytometric assay was validated and corroborated by Western analysis as previously reported [18]. Anti-Phospho-p44/42 MAPK antibody conjugated to APC was obtained from Cell Signaling (Boston, MA) and used at a ratio of 5 µl anti-phospho-MAPK into 200 µl PBS. Cells were harvested by centrifugation to a pellet, fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and then permeabilized in 90% cold (−20°C) methanol for 1 hour. They were then washed 2 times in PBS and then incubated for 1 hour in the phospho-MAPK antibody solution at room temperature, shielded from light. Relative ERK levels were measured by flow cytometry (LSRII, Becton Dickinson, Mountainview, CA) using the APC channel, where the cells are excited at 488 nm with emission collected through a 610/20 nm band pass filter.

Quantification of DNA with Propidium Iodide Staining

Cell cycle analysis was performed by hypotonic propidium iodide (PI) staining and flow cytometry as previously described [14, 17, 18]. PI staining solution was prepared as 25 mg Propidium Iodide, 500 mg NaCitrate, 500 µl Triton-X100 and 500 ml ddH20. Cells harvested by centrifugation were resuspended in 0.5 ml of PI. Relative DNA content of G1:S:G2 cells was measured by flow cytometry using 488 nm and the PE emission collection channel.

Microscopy

Cells were harvested and stained with BSA-FITC and E2-BSA-FITC exactly as stated in the protocol for flow cytometry. Cells were placed onto a covered slide and visualized using the green excitation filter of the fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX 41, Tokyo, Japan) at a magnification of 10x and 40x, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical Analyses were performed using SPSS 11.0 for Windows, Student Edition. Data was obtained by gating set at the highest 5% of control cells and recording the percent of cells with a positive signal exceeding the gate in each successive treatment group. PI data was analyzed from the percent of cells in G1 as determined by DNA histograms using BD FacsDiva software. Each treatment group was then compared to the control using a Paired-Sample T Test. All other analyses were performed utilizing the One-Sample T Test. Relative membrane estrogen receptor FITC staining was measured by the mean flow cytometric FITC signal for each treatment group, expressed as a percentage of the control. A p value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Membrane Estrogen Receptor

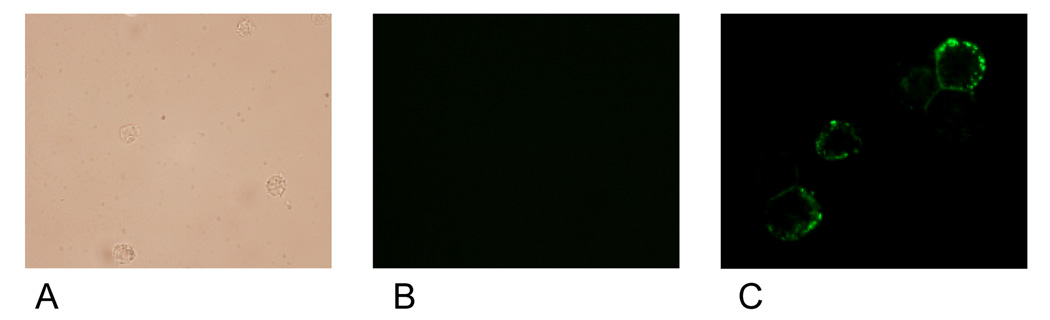

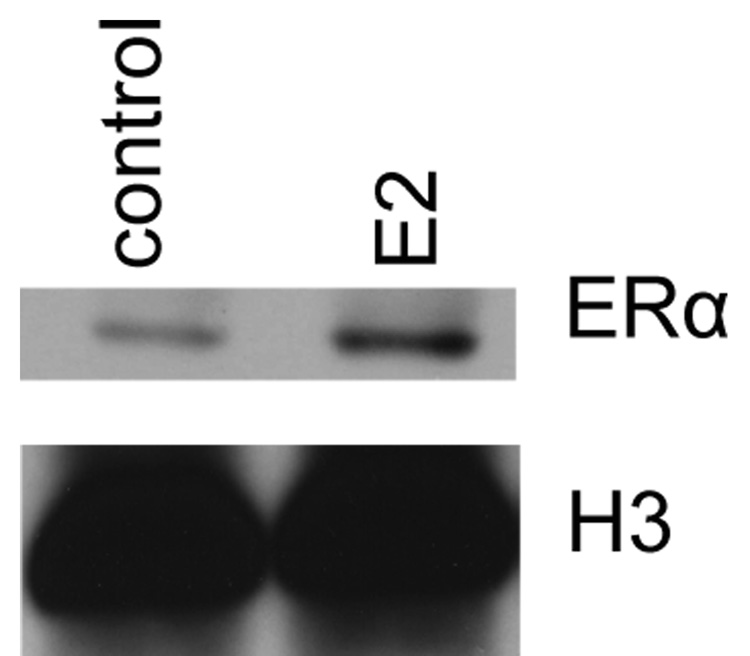

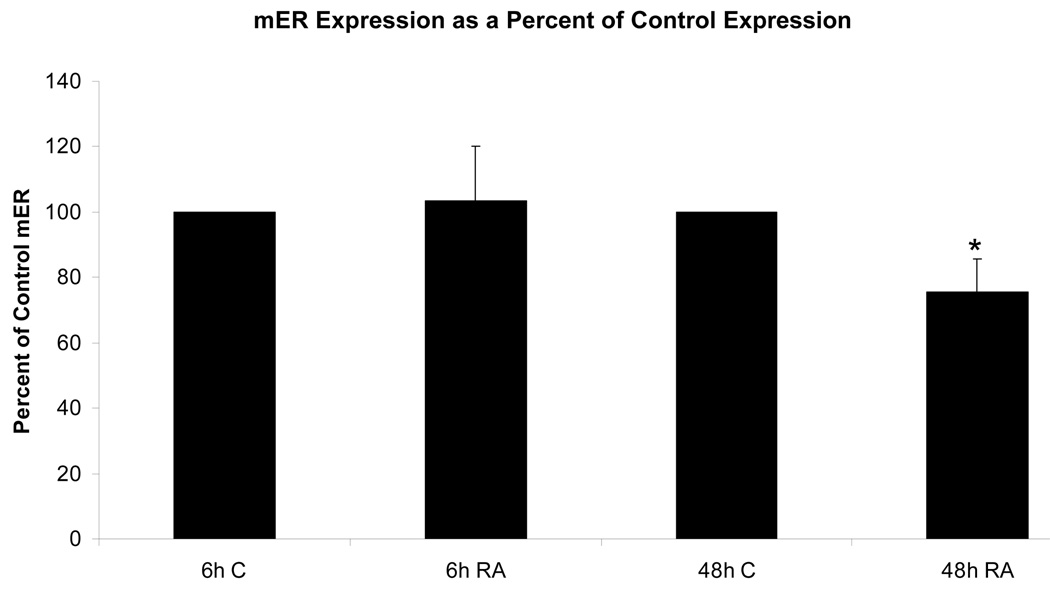

Membrane localized estrogen receptors can be detected on the plasma membrane. Viable HL-60 human myeloblastic leukemia cells were stained with β-estradiol conjugated to bovine serum albumin with covalently linked fluoresceinisothiocyanate (E2-BSA-FITC). The E2-BSA-FITC binds estrogen receptors but can not be internalized [13, 19]. E2-BSA-FITC staining correlates with antibody staining, but it has the advantage that E2-BSA is an mER agonist that causes receptor activation and hence can be used to stimulate receptor activation and study function. The stained cells were visualized using fluorescence microscopy. Figure 1 shows the fluorescent cells. The staining circumscribes the cell. Control cells stained with BSA-FITC showed no staining. Treated cells with free E2 caused increased in nuclear ERα compared to untreated controls, as expected for E2-induced nuclear translocalization (Figure 2). The E2-BSA-FITC staining was quantified by flow cytometry. Treating cells with retinoic acid (RA), an inducer of myeloid terminal differentiation and G0 cell cycle arrest of these cells [14, 17], caused a small reduction in mER expression by 48 hours as shown in Figure 3. The expression of the membrane ER is not restricted to any specific cell cycle phase. Cells were dual stained for the membrane ER using E2-BSA-FITC and for nuclear DNA using DAPI. Flow cytometry was used to analyze membrane ER expression for cells in the G1, S and G2/M phases based on DNA content. The membrane ER expression of cells in G1, S, or G2/M identified by DAPI staining was thus determined. Figure 4 shows the results for expression in S and G2/M normalized to G1 expression level to monitor change associated with cell cycle progression. The expression of membrane ER increases with progression through the cell cycle as cells transit from G1 to S to G2/M. mER thus appears to be constitutively expressed during the cell cycle without phase specific expression. This is not grossly modified by treatment with RA, where by 72 hours of treatment the population is largely G0 with few remaining S and G2/M cells. As we have reported, populations of RA-treated HL-60 cells first exhibit evidence of functional differentiation at approximately 48 hours, and the whole population is essentially differentiated in G0 by 72 – 96 hours [14, 17].

Figure 1.

Visible light (panel A) of BSA-FITC treated cells(10X), fluorescence microscopic images of BSA-FITC treated cells (10X, panel B) and E2-BSA-FITC treated cells (40X, panel C) HL-60 myeloblastic leukemia cells. The green FITC fluorescence surrounding the cells indicates the positive binding of E2-BSA-FITC to membrane estrogen receptors. When treated with BSA-FITC to measure the non-specific binding, no fluorescence was seen – either at the membrane or intracellular level.

Figure 2.

Western blot analysis of nuclear estrogen receptor á translocation upon estrogen stimulation. Histone H3 was used as loading control. E2 caused the expected increase in nuclear ERα compared to the control.

Figure 3.

Figure 3a. Effect of RA on membrane estrogen receptor (mER) expression. mER expression in RA-treated cells 6 hours after treatment changes very little from the control, with an average increase of only 3%. By 48 hours after RA treatment, expression was reduced* to only 75% of the control mER. * = p < 0.05.

Legend: C: Control; RA: Retinoic Acid;

Figure 3b. From 6 to 48 hours, the mER expression in RA-treated cells has diminished farther below the control expression (see Fig. 2) and decreased over time as well. From 6 to 48 hours, mER expression has decreased by an average of 16%.

Legend: C: Control; RA: Retinoic Acid;

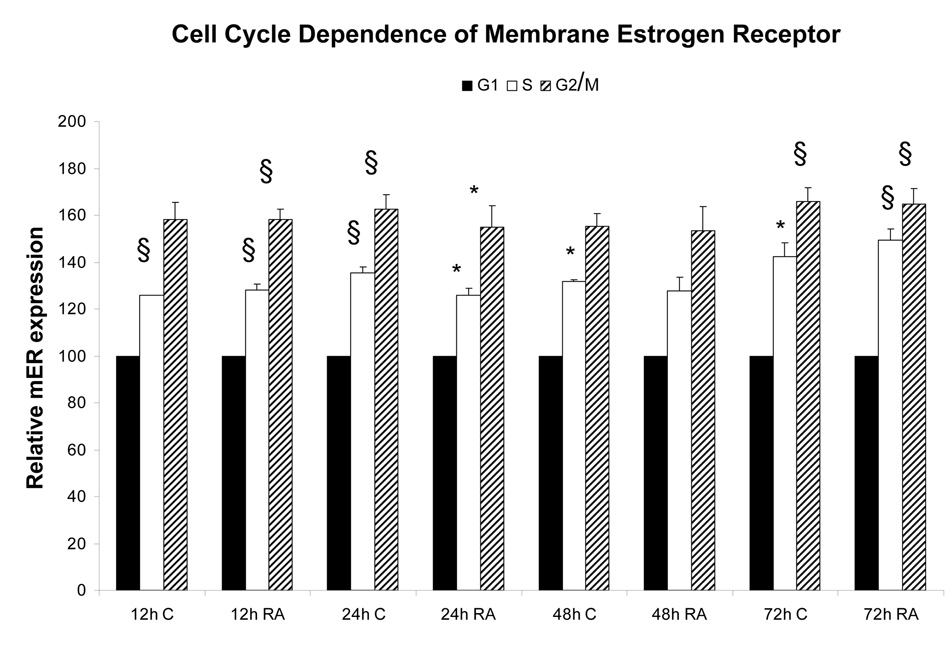

Figure 4.

Cell cycle dependence of mER expression. Cells co-stained for DNA and mER show a progressive trend with increasing mER expression from G1 to S to G2 phase. § = p< 0.01. * = p < 0.05.

Legend: C: Control; RA: Retinoic Acid;

ERK Activation

To provide evidence of a signaling function for the putative membrane ER, the effect of E2-BSA on ERK activation was determined. We wished in particular to confirm that the apparent mER detected with labeled agonist was just not a decoration but competent to signal as expected if a receptor was activated. Cells were thus treated with the agonist and then analyzed for activation of the ERK MAPK. Activated ERK was detected by enhanced occurrence of T(203)EY(205) dual phosphorylation using flow cytometry, which as reported previously correlates well with Western blotting with the same phospho-specific antibody [14, 17, 18]. Agonist induced ERK activation is reported as the percentage of cells expressing activated ERK exceeding the basal expression in 95% of untreated control cells. The results are shown in Figure 5. As reported previously, RA induced enhanced ERK activation [14, 17, 20–22]. E2-BSA induced almost the same response as RA and with kinetics previously reported upon activation of mER: ERK activation has a peak at a later time point [23], that in HL-60 mirrors the RA induced ERK activation. But the combination of E2-BSA and RA did not further increase ERK activation. Using Tamoxifen as a ligand instead of E2-BSA gave similar results as with E2-BSA. Tamoxifen also induced enhanced ERK activation, and the combination of RA and Tamoxifen also produced only a modest enhancement over only Tamoxifen, although significantly increased over just RA. Tamoxifen is an ER ligand that inhibits the nuclear transcriptional effects of classical ER function; but as for other ER antagonists, can have opposite effects for the non-classical membrane ER effects [24]. Ligand activation of the membrane ER with E2-BSA, which is membrane impermeable, or Tamoxifen, which inhibits nuclear ER function, thus caused ERK activation. The enhanced ERK activation level compared to basal levels in untreated controls was not apparent at 6 hour - or earlier (data not shown) - but was evident by 48 hours. At 24 hours there were intermediate responses (data not shown). The ligands thus evoked slow manifestation of a durable ERK activation. This is in contrast to the rapid and transient signaling response that has hitherto largely been attributed to the membrane ERs observed so far, suggesting yet another mechanism of mER signaling may exist other than rapid direct interaction. The durable MAPK signal is consistent with potential involvement in differentiation where durable MAPK signals have been construed to drive differentiation in a variety of cases [25–35]. The durable signal is thus functionally different from the transient MAPK signal that is the classical mitogenic signal. Hence in this context the slow, long MAPK signal emerging from the membrane ER agonists may affect cell differentiation. In these cells, RA-induced differentiation is known to depend on MAPK signaling [14, 17, 20–22].

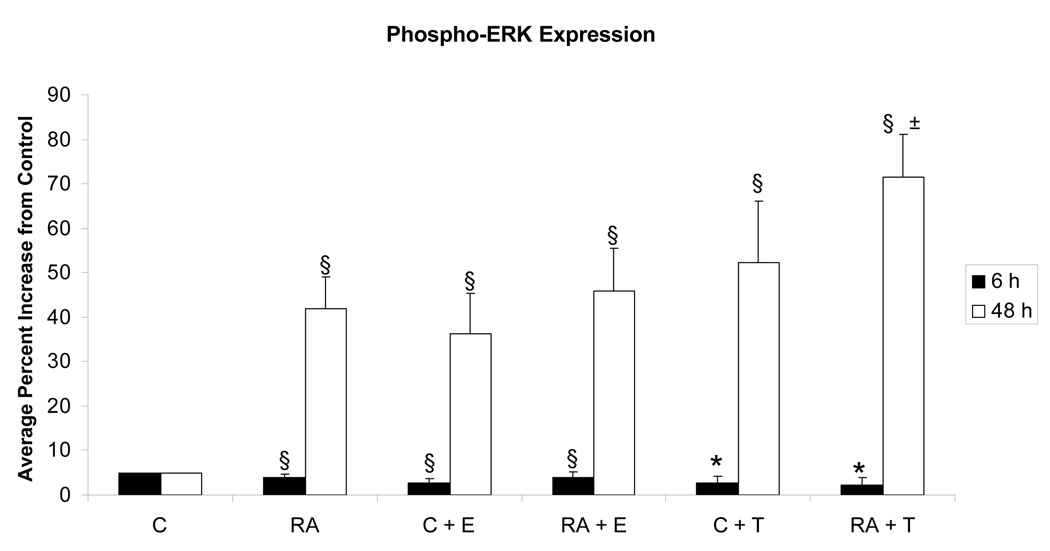

Figure 5.

Effect of E2-BSA on RA-induced ERK activation. Flow cytometry after 6 hours of RA treatment revealed that RA, E2 (E2-BSA) and RA + E2 samples show no induced ERK§ compared to the untreated control, nor do T (Tamoxifen) and RA + T samples*. After 48 hours all are significantly increased§ from the control, and RA and RA + T treatments differ± by a significance of p = 0.055. * = p < 0.05. § = p< 0.01.

Legend: C: Control; RA: Retinoic Acid; C + E: E2-BSA; RA + E: Retinoic Acid + E2-BSA; C + T: Tamoxifen; RA + T: Retinoic Acid + Tamoxifen.

Modulation of Cell Differentiation

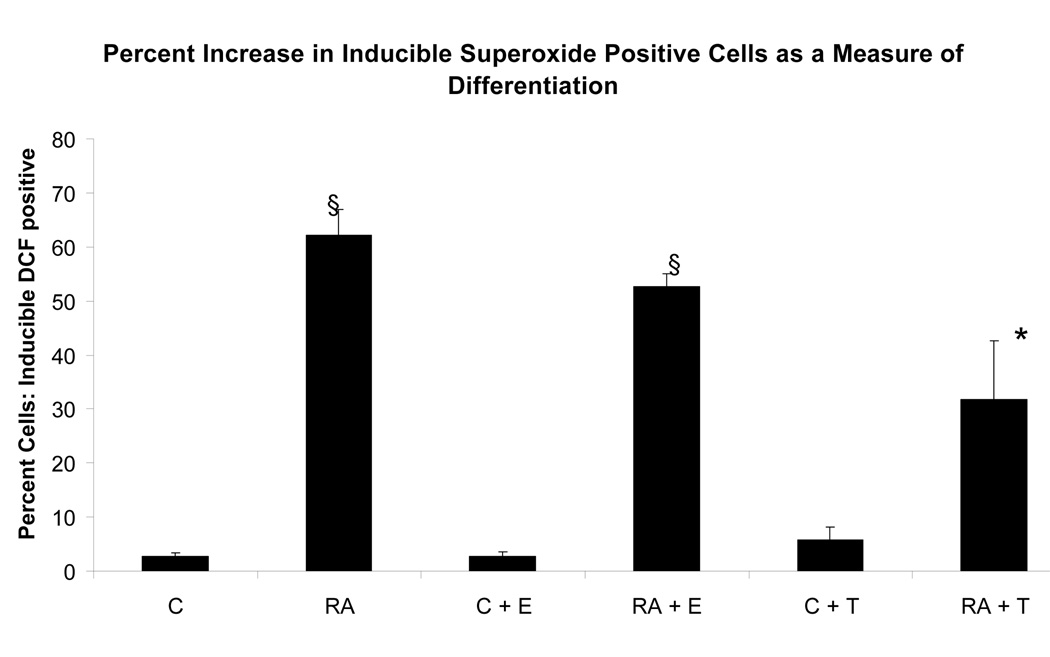

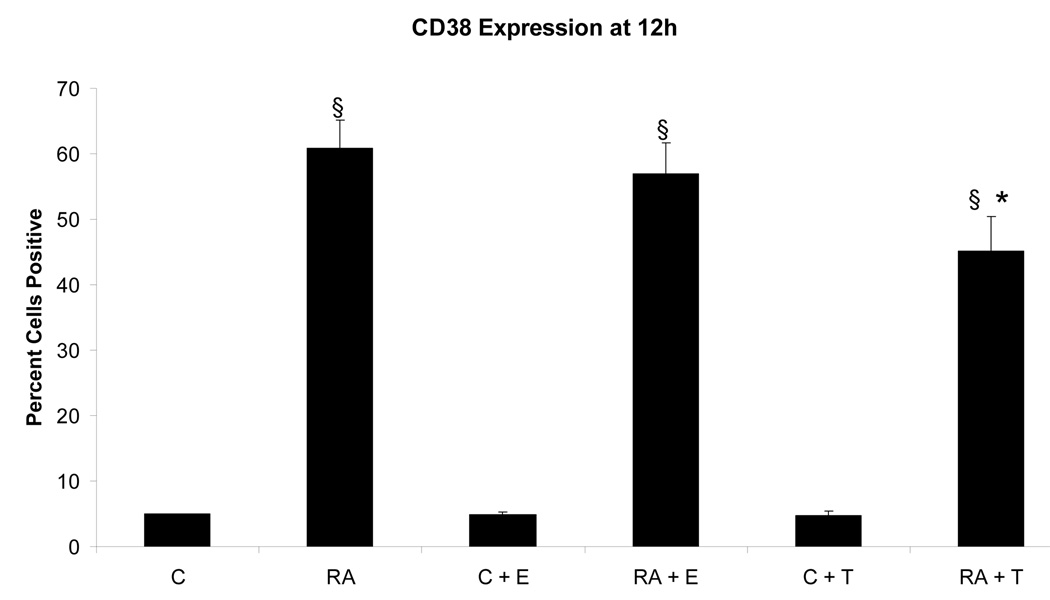

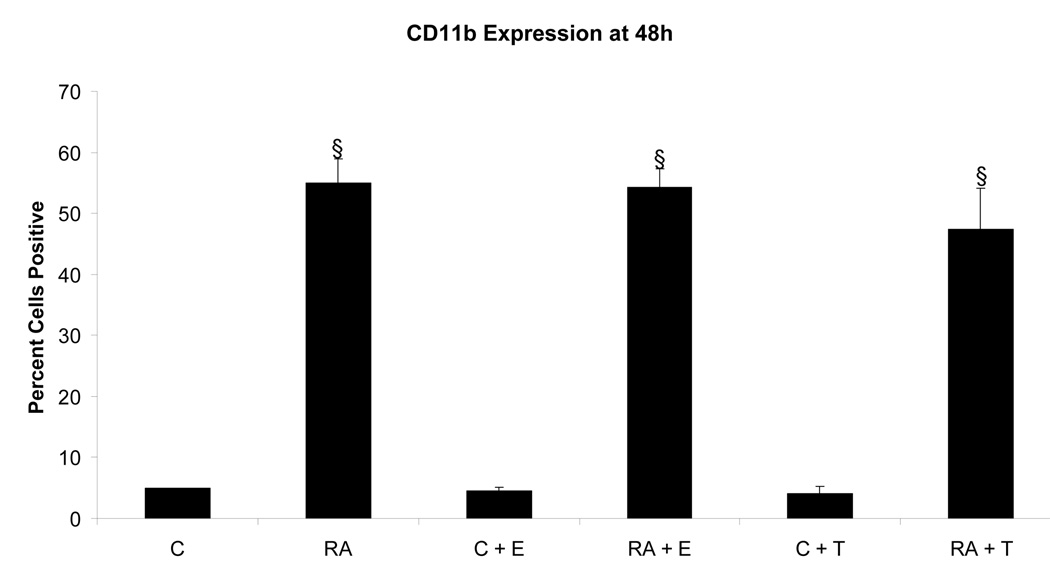

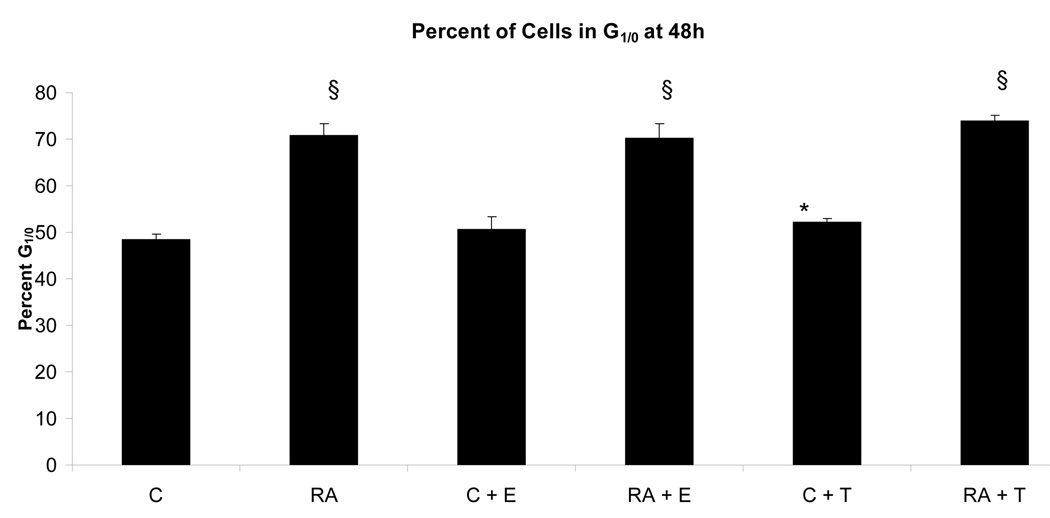

To determine if the putative membrane ER signal affected RA-induced terminal differentiation, the effect of E2-BSA on RA-induced differentiation and G0 arrest was also ascertained. The effect of Tamoxifen was also tested. Ligand binding diminished RA-induced terminal differentiation assayed by the occurrence of functional differentiation characterized by inducible oxidative metabolism. Cells were treated or not with RA plus or minus E2-BSA. Functional differentiation was measured after 48 hours using flow cytometry. Figure 6 shows the results. Cells treated with RA underwent significant differentiation typical of these HL-60 cells, where by 72 to 96 hours essentially the whole population is typically converted [14, 17, 20–22]. E2-BSA did not induce terminal differentiation, but slightly diminished RA-induced differentiation. Tamoxifen had similar but more pronounced effects inhibiting RA-induced functional differentiation. Looking at the RA-induced expression of earlier cell surface markers of phenotypic conversion, namely the CD38 ectoenzyme receptor (shown in Figure 7) and the CD11b component of integrin receptor (shown in Figure 8), indicated that effects on earlier differentiation markers occurred to a much lesser degree. E2-BSA also had no significant effect on G0 arrest in RA untreated or treated cells by 48 hours, when RA-induced G0 arrest is first clearly evident (as shown in Figure 9), or later (data not shown). Surprisingly, the membrane ER signal thus appears to interfere with the late portion of the RA-induced progression of differentiation to mature myeloid cells, in particular the occurrence of functional differentiation for inducible oxidative metabolism.

Figure 6.

Effect of E2-BSA on RA-induced functional differentiation characterized by inducible oxidative metabolism. The inducible ROS production measured by the TPA inducible DCF fluorescence (compared to TPA untreated control) in all treatment groups decreased from RA-treated cells to RA + E2 treatment by 10% and to RA + Tamoxifen treatment by 30%. RA + Tamoxifen treatment was significantly increased* from the controls and decreased§ from the RA-treated cells. * = p < 0.05. § = p< 0.01.

Legend: C: Control; RA: Retinoic Acid; C + E: E2-BSA; RA + E: Retinoic Acid + E2-BSA; C + T: Tamoxifen; RA + T: Retinoic Acid + Tamoxifen.

Figure 7.

Effect of E2-BSA on RA-induced CD38 expression. CD38 expression decreases in RA-treated cells with the addition of E2 by 4%, and decreases even farther with the addition of Tamoxifen by 16%. All treatments groups with RA were significantly increased§ from control cells. RA + Tamoxifen treated cells were significantly reduced* from RA-treated cells. § = p< 0.01* = p< 0.05.

Legend: C: Control; RA: Retinoic Acid; C + E: E2-BSA; RA + E: Retinoic Acid + E2-BSA; C + T: Tamoxifen; RA + T: Retinoic Acid + Tamoxifen.

Figure 8.

Effect of E2-BSA on RA-induced CD11b (integrin receptor). CD11b expression in RA-treated cells remains largely unchanged with the addition of E2, with an average decrease of only 1%, but decreases by 7% with the addition of Tamoxifen to the RA treatment. All treatments groups with RA were significantly increased§ from control cells. § = p< 0.01.

Legend: C: Control; RA: Retinoic Acid; C + E: E2-BSA; RA + E: Retinoic Acid + E2-BSA; C + T: Tamoxifen; RA + T: Retinoic Acid + Tamoxifen.

Figure 9.

Effect of E2-BSA on RA-induced G1/0 arrest. In all treated groups, those with RA-treatment showed no significant difference, just as those without RA-treatment remained very similar. All RA-treated had a larger percentage of cells in G1/0 than the control cells. The percentage of G1/0 cells was increased an average of s22% by RA§, 22% by RA + E2 § and 25% by RA + Tamoxifen§. Estrogen treatment alone increased G1/0 by 2% only and Tamoxifen treatment increased G1/0 by 4%*. * = p < 0.05. § = p< 0.01

Legend: C: Control; RA: Retinoic Acid; C + E: E2-BSA; RA + E: Retinoic Acid + E2-BSA; C + T: Tamoxifen; RA + T: Retinoic Acid + Tamoxifen.

DISCUSSION

A membrane ER has thus been found on a cultured hematopoietic cell that can give rise to MAPK signaling and can regulate the RA-induced differentiation of these cells. Glucocorticoid receptor (GR), another member of the steroid- thyroid hormone nuclear receptor super family, was reported to be present on the plasma membrane in leukemia and lymphoma cells [36] and to also have a higher expression towards the S-G2/M phase of the cell cycle, as we report here for mER [37]. In contrast with membrane GR which predisposes the cells to lysis [38], the membrane ER and RA pathways appear to cross talk and not affect cell viability. In HL-60 myeloblastic leukemia cells, RA is known to regulate the expression of several membrane receptors. These include CD38 [39], BLR1/CXCR [14, 40], FcγRII [41], and c-FMS [42, 43]. In each case increased expression of the receptor caused enhanced MAPK signaling and enhanced cellular differentiation in response to RA, as well as 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. This suggests that these receptors cooperate to create the durable MAPK signal needed to elicit differentiation [14, 17, 20–22]. By contrast the PDGFR, a classical MAPK signaling receptor, could differentially, namely positively or negatively, regulate different features of RA-induced phenotypic conversion, suggesting that not all receptor originated MAPK signal would coherently contribute to the same signaling pathway to drive differentiation [17]. In particular it suggested that there might be some receptor originated MAPK signals that could negatively affect aspects of RA-induced differentiation. The present results give support to this showing that the membrane ER is an example of a receptor that contributes a MAPK signal, but does not enhance RA-induced differentiation. This has potential clinical-translational implications for treatment of leukemia showing that although tamoxifen and retinoic acid have synergistic role on human breast cancer cells, this is not the case on leukemic cells. RA has also been shown to regulate the expression of certain adaptor molecules known to regulate MAPK signaling, in particular Dok1 and 2 [44], SLP-76 [45], and c-CBL [46]. In the case of SLP-76 we have shown that it specifically complexes with c-FMS to cooperatively drive ERK activation and enhance RA-induced differentiation. In contrast we found that c-CBL complexed with CD38 and promoted RA-induced differentiation. The enigma of the potentially divergent effects of different receptor originated MAPK signals may thus reflect the effects of different adaptor molecules specific for different receptors that guide the signaling of each complex. This motivates future experiments to resolve the different complexes involved. Regardless of how this is resolved, the present results make the significant demonstration that the membrane ER contributes a MAPK signal that does not contribute propulsion to RA-induced differentiation, and is inhibitory if anything. It is thus functioning in contrast to CD38, BLR1, FcγRII and c-FMS, for example, in directing cell differentiation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. James Smith of the Cornell Biomedical Sciences Flow Cytometry Core Laboratory for flow cytometry support. This work was supported in part by the NIH(USPHS) and a NYSTEM award.

This work supported in part by grants from the NIH(USPHS) (CA033505)and NYSTEM.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pietras RJ, Szego CM. Specific binding sites for oestrogen at the outer surfaces of isolated endometrial cells. Nature. 1977;265(5589):69–72. doi: 10.1038/265069a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moriarty K, Kim KH, Bender JR. Minireview: estrogen receptor-mediated rapid signaling. Endocrinology. 2006;147(12):5557–5563. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammes SR, Levin ER. Extranuclear steroid receptors: nature and actions. Endocr Rev. 2007;28(7):726–741. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weatherman RV. Untangling the estrogen receptor web. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2(4):175–176. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0406-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hewitt SC, Deroo BJ, Korach KS. Signal transduction. A new mediator for an old hormone? Science. 2005;307(5715):1572–1573. doi: 10.1126/science.1110345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Migliaccio A, et al. Tyrosine kinase/p21ras/MAP-kinase pathway activation by estradiol-receptor complex in MCF-7 cells. Embo J. 1996;15(6):1292–1300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zivadinovic D, Watson CS. Membrane estrogen receptor-alpha levels predict estrogen-induced ERK1/2 activation in MCF-7 cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7(1):R130–R144. doi: 10.1186/bcr959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qiu J, et al. Rapid signaling of estrogen in hypothalamic neurons involves a novel G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor that activates protein kinase C. J Neurosci. 2003;23(29):9529–9540. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-29-09529.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Razandi M, et al. Plasma membrane estrogen receptors exist and functions as dimers. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18(12):2854–2865. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song RX, et al. The role of Shc and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor in mediating the translocation of estrogen receptor alpha to the plasma membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(7):2076–2081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308334100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song RX, et al. Estrogen signaling via a linear pathway involving insulin-like growth factor I receptor, matrix metalloproteinases, and epidermal growth factor receptor to activate mitogen-activated protein kinase in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2007;148(8):4091–4101. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marino M, Acconcia F, Trentalance A. Biphasic estradiol-induced AKT phosphorylation is modulated by PTEN via MAP kinase in HepG2 cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14(6):2583–2591. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-09-0621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ronnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Diversity of ovarian steroid signaling in the hypothalamus. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2005;26(2):65–84. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J, Yen A. A MAPK-positive Feedback Mechanism for BLR1 Signaling Propels Retinoic Acid-triggered Differentiation and Cell Cycle Arrest. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(7):4375–4386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708471200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danel L, et al. Presence of estrogen binding sites and growth-stimulating effect of estradiol in the human myelogenous cell line HL60. Cancer Res. 1982;42(11):4701–4705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee MO, Liu Y, Zhang XK. A retinoic acid response element that overlaps an estrogen response element mediates multihormonal sensitivity in transcriptional activation of the lactoferrin gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15(8):4194–4207. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reiterer G, Yen A. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor regulates myeloid and monocytic differentiation of HL-60 cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67(16):7765–7772. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reiterer G, Yen A. Inhibition of the janus kinase family increases extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 phosphorylation and causes endoreduplication. Cancer Res. 2006;66(18):9083–9089. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taguchi Y, Koslowski M, Bodenner DL. Binding of estrogen receptor with estrogen conjugated to bovine serum albumin (BSA) Nucl Recept. 2004;2(5) doi: 10.1186/1478-1336-2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yen A, et al. Retinoic acid induced mitogen-activated protein (MAP)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) kinase-dependent MAP kinase activation needed to elicit HL-60 cell differentiation and growth arrest. Cancer Res. 1998;58(14):3163–3172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yen A, et al. Transformation-defective polyoma middle T antigen mutants defective in PLCgamma, PI-3, or src kinase activation enhance ERK2 activation and promote retinoic acid-induced, cell differentiation like wild-type middle T. Exp Cell Res. 1999;248(2):538–551. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yen A, Roberson MS, Varvayanis S. Retinoic acid selectively activates the ERK2 but not JNK/SAPK or p38 MAP kinases when inducing myeloid differentiation. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1999;35(9):527–532. doi: 10.1007/s11626-999-0063-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bulayeva NN, Gametchu B, Watson CS. Quantitative measurement of estrogen-induced ERK 1 and 2 activation via multiple membrane-initiated signaling pathways. Steroids. 2004;69(3):181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jakacka M, et al. Estrogen receptor binding to DNA is not required for its activity through the nonclassical AP1 pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(17):13615–13621. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008384200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miranda MB, Johnson DE. Signal transduction pathways that contribute to myeloid differentiation. Leukemia. 2007;21(7):1363–1377. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santos SD, Verveer PJ, Bastiaens PI. Growth factor-induced MAPK network topology shapes Erk response determining PC-12 cell fate. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(3):324–330. doi: 10.1038/ncb1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cowley S, et al. Activation of MAP kinase kinase is necessary and sufficient for PC12 differentiation and for transformation of NIH 3T3 cells. Cell. 1994;77(6):841–852. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kondo A, et al. Coupling of Grb2 to Gab1 mediates hepatocyte growth factor-induced high intensity ERK signal required for inhibition of HepG2 hepatoma cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(3):1428–1436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704999200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanz C, et al. Strict regulation of c-Raf kinase levels is required for early organogenesis of the vertebrate inner ear. Oncogene. 1999;18(2):429–437. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perez-Juste G, Aranda A. Differentiation of neuroblastoma cells by phorbol esters and insulin-like growth factor 1 is associated with induction of retinoic acid receptor beta gene expression. Oncogene. 1999;18(39):5393–5402. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramp U, et al. Uniform response of c-raf expression to differentiation induction and inhibition of proliferation in a rat rhabdomyosarcoma cell line. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol. 1990;59(5):271–280. doi: 10.1007/BF02899414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacNicol AM, Muslin AJ, Williams LT. Raf-1 kinase is essential for early Xenopus development and mediates the induction of mesoderm by FGF. Cell. 1993;73(3):571–583. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90143-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kharbanda S, et al. Activation of Raf-1 and mitogen-activated protein kinases during monocytic differentiation of human myeloid leukemia cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(2):872–878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rommel C, et al. Differentiation stage-specific inhibition of the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway by Akt. Science. 1999;286(5445):1738–1741. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmidt M, et al. Ras-independent activation of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway upon calcium-induced differentiation of keratinocytes. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(52):41011–41017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003716200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen F, Watson CS, Gametchu B. Association of the glucocorticoid receptor alternatively-spliced transcript 1A with the presence of the high molecular weight membrane glucocorticoid receptor in mouse lymphoma cells. J Cell Biochem. 1999;74(3):430–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gametchu B, et al. Plasma membrane-resident glucocorticoid receptors in rodent lymphoma and human leukemia models. Steroids. 1999;64(1–2):107–119. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(98)00097-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gametchu B. Glucocorticoid receptor-like antigen in lymphoma cell membranes: correlation to cell lysis. Science. 1987;236(4800):456–461. doi: 10.1126/science.3563523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lamkin TJ, et al. Retinoic acid-induced CD38 expression in HL-60 myeloblastic leukemia cells regulates cell differentiation or viability depending on expression levels. J Cell Biochem. 2006;97(6):1328–1338. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Battle TE, Levine RA, Yen A. Retinoic acid-induced blr1 expression promotes ERK2 activation and cell differentiation in HL-60 cells. Exp Cell Res. 2000;254(2):287–298. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wightman J, et al. Retinoic acid-induced growth arrest and differentiation: retinoic acid up-regulates CD32 (Fc gammaRII) expression, the ectopic expression of which retards the cell cycle. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1(7):493–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yen A, et al. FMS (CSF-1 receptor) prolongs cell cycle and promotes retinoic acid-induced hypophosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein, G1 arrest, and cell differentiation. Exp Cell Res. 1996;229(1):111–125. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yen A, Sturgill R, Varvayanis S. Increasing c-FMS (CSF-1 receptor) expression decreases retinoic acid concentration needed to cause cell differentiation and retinoblastoma protein hypophosphorylation. Cancer Res. 1997;57(10):2020–2028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lamkin TJ, Chin V, Yen A. All-trans retinoic acid induces p62DOK1 and p56DOK2 expression which enhances induced differentiation and G0 arrest of HL-60 leukemia cells. Am J Hematol. 2006;81(8):603–615. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yen A, et al. Retinoic acid induces expression of SLP-76: expression with c-FMS enhances ERK activation and retinoic acid-induced differentiation/G0 arrest of HL-60 cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 2006;85(2):117–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen MaY, A c-Cbl interacts with CD38 and promotes RA-induced differentiation and G0 arrest of human myeloblastic leukemia cells. Submitted. 2008 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]