Abstract

Heterogeneity is an important property of any population experiencing a disease. Here we apply general methods of the theory of heterogeneous populations to the simplest mathematical models in epidemiology. In particular, an SIR (susceptible-infective-removed) model is formulated and analyzed when susceptibility to or infectivity of a particular disease is distributed. It is shown that a heterogeneous model can be reduced to a homogeneous model with a nonlinear transmission function, which is given in explicit form. The widely used power transmission function is deduced from the model with distributed susceptibility and infectivity with the initial gamma-distribution of the disease parameters. Therefore, a mechanistic derivation of the phenomenological model, which is believed to mimic reality with high accuracy, is provided. The equation for the final size of an epidemic for an arbitrary initial distribution of susceptibility is found. The implications of population heterogeneity are discussed, in particular, it is pointed out that usual moment-closure methods can lead to erroneous conclusions if applied for the study of the long-term behavior of the models.

Keywords: SIR model, heterogeneous populations, transmission function, distributed susceptibility

1 Introduction

Mathematical modeling of epidemics arguably began with the pioneer work of Ross [35] and developed considerably ever since (e.g., [4, 5]). Especially significant contribution was made by Kermack and McKendrick [26], two students of Ross, who considered the situation of microparasite infection, where contacts between individuals are made according to the law of mass-action, all individuals are identical, the population is closed, and the population size is large enough to apply a deterministic description (for a brief review see [7]). Additionally, if it is assumed that the individuals are infected for an exponentially distributed period of time, then a usual SIR model in the form of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) can be written down for the sizes of susceptible, infective and removed classes.

Since the work of Kermack and McKendrick a great deal of mathematical models were suggested that relax one or more assumptions that led to the Kermack–McKendrick model. A substantial part of this work was devoted to incorporate heterogeneity into the mathematical models, which is also the main subject of the present text. In what follows we retain the assumptions of random mixing, no inflow of susceptible or infected hosts, exponentially distributed infectious period, and validity of deterministic description. Specifically, we will look into heterogeneity in disease parameters (such as susceptibility to a disease); disease parameters are considered as an inherent and invariant property of individuals, whereas the parameter values can vary between individuals.

The most common way to take into account parametric heterogeneity is to divide population into groups [9, 16, 17, 18], usually a small number of groups. An important disadvantage of the subgroup approach is that heterogeneity within a group cannot be incorporated if a fixed number of groups is considered. Another approach, which we pursue here, is to consider the population as having a continuous distribution (see, e.g., [5, 6, 7, 10, 11, 12, 33, 39]), which can be a limiting case of a discrete group model as it was done by May and Anderson [31] (eventually they used a continuous gamma-distribution).

Our approach to formulate mathematical models is close to that applied in, e.g., [12], where known experimental data forced the authors to take into account heterogeneity among hosts in their susceptibility to the virus among other key details, and a simple SIR model was adjusted to account for new information. The major novelty of the present text is to introduce the well developed theory of heterogeneous populations into the epidemiological modeling. Using simple models we are able to obtain known results with less effort, and, more importantly, produce new analytical results. In particular, we show that a heterogeneous SIR model with distributed susceptibility can be reduced to a homogeneous one with a nonlinear transmission function; the exact form of this function is given. It turns out that widely applied nonlinear transmission function in the form of power relationship, βSpIq, can be a consequence of the intrinsic heterogeneity in susceptibility and infectivity parameters. For a heterogeneous SIR model the equation for the final epidemic size is found. The explicit form of the final epidemic size emphasizes and illustrates the fact that the goal to model the evolution of a heterogeneous population for a long time can be accomplished only if the exact initial distribution is available. Any moment-closure methods may lead to erroneous estimates.

Our paper is organized as follows. In Section 2 we formulate the basic models and discuss various assumptions that may lead to them. In Section 3 we review the necessary analytical tools from the theory of heterogeneous populations. In Section 4 a homogeneous model that is equivalent to the heterogeneous one is explicitly constructed, and it is shown that the former has a nonlinear transmission function; moreover, the well known power transmission function is shown to be a consequence of the initial gamma-distribution. In Section 5 the influence of heterogeneity on the disease course is studied for an SIR model with distributed susceptibility, in particular, the final size of an epidemic is found for an arbitrary initial distribution. Section 6 devoted to discussion and conclusions. Finally, in Appendix we collect the definitions of the probability distributions used throughout the text together with some auxiliary facts from the general theory of heterogeneous models.

2 The basic models with population heterogeneity

2.1 The model with distributed susceptibility

Suppose that each individual of a (sub-)population has its own value of a certain trait (which can be, e.g., susceptibility to a particular disease, social behavior, infectivity, or a hereditary attribute) that describes his or her invariant property and has a marked influence on the spread of the disease at the population level; that is, the key parameters that determine disease evolution in the total population depend on the trait values and we can speak of the trait distribution or the parameter distributions (in general, we speak of a distribution when no ambiguity is expected). The trait value remains unchanged for any given individual during the time period we are interested in, but varies from one individual to another. Any changes of the mean, variance and other characteristics of the trait distribution in the population (or the parameter distributions) are caused only by variation of population structure.

For the moment we assume that the susceptible subpopulation is heterogeneous, and denote s(t,ω) the density of susceptible individuals at time t having trait value ω (i.e., the size of subpopulation of susceptible hosts having trait values in the range from ω to ω+ dω is approximately equal to s(t, ω)dω, and the total size of the susceptibles S(t) = ∫Ω s(t, ω)dω, where Ω is the set of trait values). Assuming that the subpopulation of infectives is homogeneous (under the modeling situation), the total size of the population is constant, the disease course keeps within the simplest situation “susceptible”→“infective” → “removed”, the contact process is described by the so-called mass-action kinetics (i.e., the contact rate is proportional to the total population size N [5, 14, 32]), and that the rate of change in the susceptibles is determined by the transmission parameter, which is a function of trait values, we can write down the following equation for the change in the susceptible subpopulation having trait value ω:

| (1) |

where I(t) is the size of the subpopulation of infectives, and β(ω) incorporates information on the contact rate and the probability of a successful contact. Hereinafter we assume that the trait that characterizes susceptible individuals is the susceptibility to the disease, although it can be assumed that different individuals have different contact rates (in the latter case it becomes difficult to interpret the equation for the infectives, see below).

The change in the infective class, if the length of being infective is distributed exponentially with the mean time 1/γ, is given by

| (2) |

where we used the following notations:

Hence, β̄(t) is the mean value of the function β(ω), and ω has the probability density function (pdf) ps(t, ω) for any time moment t. We need to supplement the model (1)-(2) with the initial conditions

| (3) |

and with the third equation for the removed dR(t)/dt = γI(t). Here S0 and I0 are the initial sizes of the susceptibles and infectives respectively, and ps(0, ω) is the given initial distribution.

The model (1)-(3) is the basic model we study in this paper. This model was formulated from the first principles, as it was done for conceptually similar models in [12] for the transmission of virus in gypsy moths, in [33] for the effect of antimicrobial agents on microbial populations, in [31] for the spread of HIV in the human population, and in [39] for a class of SIS models (we note, however, that in the last two examples the frequency-dependent transmission was employed [32], and the heterogeneity of the contact rates was modelled).

The model (1)-(3) can be also deduced from the general epidemic equation (see [5])

| (4) |

where A(τ, ω, η) is the expected infectivity of an individual that was infected τ units of time ago while having trait value η towards a susceptible with trait value ω. If we assume that A(τ, ω, η) = β(ω) exp {−γτ}, and set

after some algebra we obtain (1)-(3) (see also [7]). As a side remark we note that letting A(τ, ω, η) = β(ω)χ(T − τ), where χ(t) is the Heaviside function, we obtain the model studied in [12].

2.2 Model with distributed infectivity

It can be also assumed that the population of infectives is heterogeneous. Now let β(ω) be the infectivity of an individual with trait value ω, and i(t, ω) be the density of the infective hosts with trait value ω at time moment t, I(t) = ∫Ω i(t, ω) dω. For simplicity we assume that the susceptible hosts are homogeneous. The change in the infective subpopulation should incorporate the law that specifies which trait value is assigned to a newly infected individual, and can be described by the following equation:

| (5) |

where ψ(ω, ω′) is the probability that a newly infected individual gets trait value ω if infected by an individual with trait value ω′. The change in the population S(t) is given by

| (6) |

where now β̄(t) = ∫Ωβ(ω)pi(t, ω) dω, and pi(t, ω) = i(t, ω)/I(t).

The need to specify function ψ(ω, ω′) precludes the interpretation of the function β(ω) in Section 2.1 as the heterogeneity in the contact rates. It was assumed that the infectives are all identical, and thus the supposition that an individual that has had the trait value ω turns into another identical infective host is not warranted.

A variety of choices for the function ψ(ω, ω′) is possible, but we especially interested in the particular case when a newly infected individual gets the same trait value that was possessed by the individual who passed the infection, namely

where δ(ω) is the Dirac delta function (which can correspond to modeling a situation when several different strains of an infection can be passed on). In this case the equation (5) simplifies to the equation, which is very similar to (1):

| (7) |

Model (6)-(7) is another example of a simple mathematical model for the spread of an infectious disease in a closed population with heterogeneities. The list of possible models can be easily extended. For instance, it is straightforward to assume that the parameter γ is not constant for the infected individuals, but rather is distributed with a known initial distribution. In this case the equation for the infectives takes the form

where β is now constant. Another obvious generalization is to assume that several model parameters are distributed (see Section 4.2 for an example).

In general, models (1)-(3) and (6)-(7) are infinite-dimensional dynamical systems where the evolutionary operator specifies complex transformations of the initial distributions. Such models are less amenable to qualitative, quantitative, or numerical analysis than their finite-dimensional analogues formulated in terms of ODEs. A usual practice is to formulate an infinite-dimensional system of ODEs for which some approximations methods (e.g., assuming that the initial distribution is close to the normal distribution [33]), moment-closure ([10, 11] and [8]), or numerical methods ([39]) can be applied. We show below that in some particular cases, when the analytical form of the heterogeneous models meets certain requirements, the initial model can be reduced to a low-dimensional ODE model, which, in turn, can be effectively analyzed.

3 The necessary facts from the theory of heterogeneous populations

To keep the exposition self-contained and for the sake of convenience of references we briefly survey the necessary results from [21, 23]. We present the results in the form suitable for our goal noting that more general cases can be analyzed [23]. For the proofs we refer to [25], where similar models are considered. Some additional facts are given in Appendix.

Let us assume that there are two interacting populations whose dynamics depend on trait values ω1 and ω2 respectively. The densities are given by n1(t, ω1) and n2(t, ω2), and the total population sizes N1(t) = ∫Ω1 n1(t, ω) dω1 and N2(t) = ∫Ω2 n2(t, ω) dω2. Obviously, more than two populations can be considered, or some populations may be supposed to be homogeneous; we choose two not to be drowned in notations. Assume next that the net reproduction rates of the populations have the specific form:

| (8) |

where ϕi(ωi) are given functions, ϕ̄i(t) = ∫Ωi ϕi(ωi)pi(t, ωi) dωi are the mean values of ϕi(ωi), and pi(t, ωi) = ni(t, ωi)/Ni(t) are the corresponding pdfs, i = 1, 2. We also assume that ϕi(ωi), considered as random variables, are independent. The system (8) plus the initial conditions

| (9) |

define, in general, a complex transformation of densities ni(t, ωi). For the approach to study such systems based on the analysis of abstract differential equations in Banach spaces we refer to [1, 2, 3]. Another approach to analyze models in the form (8) was suggested in [21]. The latter is more attractive because eventually one has to deal with systems of ODEs of low dimensions (examples of model analysis are given in [22, 24, 25, 34]).

Let us denote

the moment generating functions (mgfs) of the functions ϕi(ωi), Mi(0, λ) are the mgfs of the initial distributions, i = 1, 2, which are given.

Let us introduce auxiliary variables qi(t) as the solutions to the differential equations

| (10) |

where indexes that exceed 2 are counted modulo 2.

The following theorem holds

Theorem 1

Suppose that t ∈ [0, T), where T is the maximal value of t such that (8)-(9) has a unique solution. Then

(i) The current means of ϕi(ωi), i = 1, 2, are determined by the formulas

| (11) |

and satisfy the equations

| (12) |

where are the current variances of ϕi(ωi), i = 1, 2.

(ii) The current population sizes N1(t) and N2(t) satisfy the system

| (13) |

where indexes that exceed 2 are counted modulo 2.

Theorem 1 gives a method of computation of the main statistical characteristics of ϕi(ωi); the analysis of model (8)-(9) is reduced to analysis of ODE system (10),(11),(13), the only thing we need to know is the mgfs of the initial distributions; the evolution of distributions can also be analyzed [23].

It is worth emphasizing that all the model we consider in this note are deterministic, and the language of probability theory is used because it is very convenient to use probabilistic terms while speaking of evolution (again, deterministic) of distributions. In this respect the discussion of well-posedness of the problem (11), (13) merits some considerations.

It is well known that a mgf, if it exists, defines uniquely the underlying distribution. It is also known that for some distributions the corresponding mgfs do not exist for any λ > 0 (an example is a log-normal distribution, see Appendix, equation (33)). The reason for this is the heavy tails of some distributions. From (11) it can be seen that the mgfs are evaluated at qi(t), for which the initial conditions qi(0) = 0. Therefore, for some distributions, if q̇i > 0, the problem (11), (13) cannot be solved at all, and for some distributions, the solution blows up at a finite time (which is the reason to have const T in Theorem 1). From the point of view of mathematical modeling such situations as nonexistence of solutions or blow-ups in finite time are the consequences of some unrealistic assumptions. In particular, it is a consequence of the assumption that there are infinitely large parameter values, albeit with extremely small probabilities (more on such situations can be found in [22]). To deal with such situations it can always be assumed that the support of the initial distribution is [a, b] ∈ [0, ∞), i.e., to consider truncated distributions. In this case the problem (11), (13) is well-posed.

The particular form of the model (8) also specifies exactly what kind of restrictions on the types of heterogeneity can be handled with the considered approach. In the literature on the heterogeneity in epidemiological models the discussions are usually around three aspects. First, this is heterogeneity of hosts when the probability to transmit a disease, given a contact, depends on individuals’ susceptibility and infectivity, and this is exactly what we deal with in this paper. Second, this is heterogeneity in contact rates, which cannot be handled with the discussed approach (except in extremely simple cases) because the system (8) yields that each subpopulation should have its own parameter, whereas modeling of contact structure would imply that individuals of the whole population are characterized by trait values irrespective of whether they are susceptible or infective. And third, the distributions of latent and infectious periods; for the latter in the considered framework the discussion is restricted to the case when different individuals can have exponential distributions with different means.

In short, using the theory, outlined in this section, we can model communities of populations when each population is characterized by its own parameter value, and the relative growth rate depend on this parameter and the average characteristics of other distributions.

Concluding this sections we note that, with obvious notation changes, models (1)-(3) and (6)-(7) fall into the general framework of the master model (8).

4 Homogeneous models with nonlinear transmission functions

4.1 Reduction to a system of ODEs

We start with the equation (1), other equations in the system can be quite arbitrary, e.g., the full system can contain the class of exposed or several infective classes. Here we show that a heterogeneous model that contains (1) as a modeling ingredient can be reduced to a homogeneous model with a nonlinear transmission function whose explicit form is determined by the initial distribution of susceptibility. This result is close to the analysis in [39] where it was argued that the model with heterogeneities can be encapsulated in a homogeneous model. Due to the fact that the model considered in [39] is substantially more general than the models we consider here, no explicit formulas were found. In the case of model (1) nonlinear transmission function can be found in the exact form for different initial distributions.

According to Theorem 1 we can rewrite equation (1) in the form

| (14) |

where dots denote equations that govern the dynamics of other subpopulations, e.g., those can be usual equations for infected and removed classes. M(0, λ) is the given mgf of ps(0, ω).

Proposition 1

Model (14) is equivalent to the following model:

| (15) |

where dots denote the same as in (14),

| (16) |

and M−1(0, ξ) is the inverse function to mgf M(0, λ).

Proof

The first equation in (14) can be rewritten in the form

From (11) β̄(t) can be represented as , which, together with the previous, gives

or, using the initial conditions S(0) = S0, q(0) = 0,

| (17) |

which is the first integral to system (14). Knowledge of a first integral allows to reduce the order of the system by one. Since M(0, λ) is an absolutely monotone function in the case of nonnegative β(ω) ⩾ 0, then it follows that

| (18) |

where M−1(0, M(0, λ)) = λ for any λ.

or, by the inverse function theorem, (15) with (16).

The simple properties of the nonlinear incidence function h(S) are h(0) = 0, h(S0) = S0β̄(0), h′ (S) > 0.

Let us consider several examples. Definitions for the probability distributions we use can be found in Appendix. In all examples it is assumed that β(ω) = ω, i.e., the transmission coefficient takes the values from the domain of ω with the probabilities corresponding to ps(t, ω).

If the initial distribution is a gamma-distribution with parameters k and ν (see Appendix, (30)) we obtain

| (19) |

If k = 1 (i.e., the initial distribution is exponential with mean 1/ν), then h(S) = S2/(νS0). Expression (19) was first obtained in [12] and later used as a nonlinear incidence function in [10].

If the initial distribution is an inverse gaussian (Wald) distribution with parameters μ and ν (the defnition is given in Appendix, equation (31)), then

| (20) |

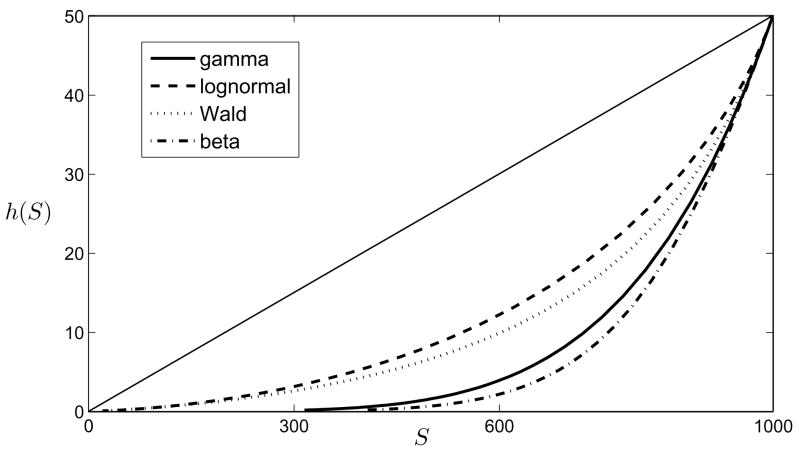

In a similar vein other initial distribution can be analyzed, but not all of them have an explicit expression for mgf. Other examples of possible initial distributions are uniform distribution with parameters a and b, lognormal distribution, beta-distribution, Weibull distribution, Pareto distribution and many others (see Fig. 1 for four different probability distributions).

Figure 1.

The functions h(S) given by (16) for four different probability distributions with the same means and variances. The straight line shows the same function for the homogeneous model h(S) = βS. Definitions of the probability distributions are given in Appendix

The theory we briefly presented in Section 3 is equally valid both for continuous and discrete distribution. For instance, if the initial distribution is the Poisson distribution with parameter θ (Appendix, equation (35)), then we obtain

| (21) |

Note that in the case of the Poisson distribution there is non-zero probability that a randomly chosen individual has zero transmission coefficient, i.e., the Poisson distribution implies that some individuals are immune.

4.2 Derivation of the power transmission function

In standard epidemiological models the incidence rate (the number of new cases in a time unit) was frequently used as a bilinear function of infective and susceptible populations: ∝ SI. In addition to this it is usually argued that there are a variety of reasons that the standard bilinear form may require modification, including the assumption of heterogeneous mixing [28, 36]. We refer to a review paper on the subject [32] for a general account of different models for incidence rates, while noting that one of the most widely used models has the form

| (22) |

and is of direct interest to our study. The incidence rate in the form (22) was first used in [37], with the restriction that p, q < 1, but generally it is only required that p, q > 0, see also [15, 27, 29]. It is interesting to note in the context of our exposition that the exponents p, q in (22) were dubbed as “heterogeneity parameters,” but the model itself is considered phenomenological and lacking mechanistic derivation [32].

A special case of (22) is q = 1, which was considered in [13, 38]; the values for parameter p were considered p > 1. Comparison of the model (22) with the ODE (15) when the initial distribution of the susceptible subpopulation is a gamma-distribution (see (19)) let us state the following corollary.

Corollary 1

The power relationship (22) of the incidence rate in an SIR model for the case q = 1, p = 1 + 1/k > 1 can be obtained as a consequence of the heterogeneous model (1)-(3) when the initial distribution of the susceptible subpopulation is a gamma-distribution with parameters k and ν (see (30)).

As expected, letting k → ∞ and having k/ν fixed we obtain the population where everyone has the same susceptibility, and, consequently, the spread of infection is described with the standard bilinear term.

Let us assume that not only the susceptibles are heterogeneous for some trait that in-fluences the disease evolution, but also the infectives are heterogeneous, and consider the simplest possible SI model. Let s(t, ω1) and i(t, ω2) be the densities of the susceptibles and infectives respectively, here we assume that the effects of the two traits on transmission are independent, i.e., β(ω1, ω2) = β1(ω1)β2(ω2). The last assertion is a serious oversimplification, as it is natural to assume that infectivity might influence the susceptibility of contacted individual, but we need it to apply the general theory from Section 3.

The number of susceptibles with the trait value ω1 infected by individuals with trait value ω2 is given by β1(ω1)s(t, ω1) β2(ω2)i(t, ω2), and the total change in the infective class with trait value ω2 is β2(ω2)i(t, ω2) ∫Ω1 β1(ω1)s(t, ω1) dω1; an analogous expression applies to the change in the susceptible population. Combining the assumptions we obtain the following model:

| (23) |

Model (23) is supplemented with initial conditions s(0, ω1) = S0ps(0, ω1), i(0, ω2) = I0pi(0, ω2). In (23) it is assumed that if an individual having trait value ω1 was infected by an individual with trait value ω2 he or she becomes an infective with trait value ω2 (see Section 2.2). The global dynamics of (23) is simple and is similar to the simplest homogeneous SI model.

According to Theorem 1 the system (23) can be reduced to a four-dimensional system of ODEs. Reasoning exactly as in the proof of Proposition 1 we obtain

Proposition 2

The model (23) is equivalent to the model

where hi(x) is given by (16).

Combining Proposition 2 with (19) we get

Corollary 2

The power relationship (22) of the incidence rate in an SI model for the case q = 1 + 1/k2 > 1, p = 1 + 1/k1 > 1 can be obtained as a consequence of the heterogeneous model (23) when the initial distributions of the susceptibles and the infectives are gamma-distributions with parameters k1, ν1 and k2, ν2 respectively.

Consequently, it turns out that the power relationship (22), at least for the case p, q ⩾ 1, can be explained on the mechanistic basis by the inherent heterogeneities in susceptibility and infectivity of the populations. Its exact form is the consequence of the initial gamma-distributions, but we note that any of the transmission functions given in the previous subsection can be well approximated by (19) (see also Fig. 1).

5 The influence of population heterogeneity on the disease course

Here we mainly restrict our attention to the model (1)-(3) and study its global behavior. First we state almost obvious proposition:

Proposition 3

Let S1(t) = ∫Ω s1(t, ω) dω be the solution of (1)-(3) with the initial condition s1(0, ω) = S0p1(0, ω), and S2(t) =∫Ω s2(t, ω) dω be the solution of (1)-(3) with the initial condition s2(0, ω) = S0p2(0, ω), such that β̄1(0) = β̄2(0) and , where β̄i(0) =∫Ω β(ω)pi(0, ω) dω and , i = 1, 2. Then there exists ε > 0 such that S1(t) > S2(t) for all t ∈ (0, ε).

The gist of this proposition is very simple: the more heterogeneous the susceptible hosts, the less severe the initial disease progression under the model (1)-(3).

Proof

Differentiating the first equation in (14) and using (12) we get

or, at the initial time moment, . Since S(t) is continuous the proposition follows.

We remark that this proposition also holds for more general model (14). Moreover, we can replace equation (1) with equation

where dots denote terms describing demography, migration or the lost of immunity by removed individuals, the only condition is that these terms cannot depend on β(ω). Even in this case Proposition 3 still holds. For the model (5)-(6) the opposite proposition is true: the more heterogeneous the infective class in infectivity, the more severe the disease progression, which follows from the fact that β̄′(t) > 0 in this case, and, consequently, .

It is interesting to note that in the case of frequency-dependent transmission knowledge of only the initial variances of the parameter distributions does not allow inference on the short ran behavior [39].

One of the main characteristic of SIR models is the final size of the disease, which is often expressed in the number (or proportion) of susceptibles that are never infected. For the Kermack-McKendrick model

it is well known that the desired number, which we denote as S(∞), is given by the root of the equation

| (24) |

on the interval (0, S0). Here N is the constant size of the population. It is easy to show that this root always exists.

Recall that M(0, λ) is the mgf of the initial parameter distribution. For the model (1)-(3) the following theorem holds.

Theorem 2

The size of the susceptible subpopulation that escapes infection within the framework of the model (1)-(3) is given by the solution of the equation

| (25) |

satisfying condition 0 < S(∞) < S0.

Proof

First we note that exactly as it was done in Proposition 1, we can reduce the system (1)-(3) to the system

| (26) |

Using (16) and dividing the first equation in (26) by the third one we obtain

Integrating from 0 to ∞ gives

Using the identities R(∞) = N − S(∞) (since I(∞) = 0) and M−1(0, 1) = 0 we obtain

from which (25) follows. Due to the fact that M(0, λ) is an increasing function, the solution of (25) satisfying 0 < S(∞) < S0 is unique.

Remark

If we consider undistributed parameter (formally, we can let β(ω) = β = const, or, equivalently, s(0, ω) = S0δ(ω − ω̄), β(ω̄) = const, where δ(ω) is the delta-function), we obtain (24) from (25).

Arguing in the same spirit as it is done in [5] (e.g., p. 183), the problem of the epidemic invasion can be considered. We speak of the epidemic invasion here within the deterministic models: that is, an epidemic can invade the population if its basic reproductive number R0[6] is more than unity, and cannot if R0 < 1. Assuming that initially the whole population is susceptible (formally, for our model, S(−∞) = N, q(−∞) = 0), from (25) the equation for the fraction of susceptible population that does not get infected follows:

| (27) |

Here z = S(∞)/N. Equation (27) always has the root z = 1. If the basic reproductive number, defined here as

| (28) |

satisfies the condition R0 > 1, then there is another root of (27) in the interval 0 < z < 1. This root gives the sought fraction. The proof of the existence of this root under the threshold condition R0 > 1 is straightforward and can be conducted similar to the homogeneous case (e.g., [5]). This result can be illustrated by the case when the initial distribution is exponential with parameter ν: the equation for z is quadratic: R0z2 − (1 + R0)z + 1 = 0, where R0 = N/(γν). This equation has the roots 1 and 1/R0. If R0 > 1 then the fraction of susceptible population that escapes the disease is 1/R0.

Comparing the results obtained for the heterogeneous SIR model (1)-(3) with the well known results for the simple homogeneous SIR model, we can conclude that the questions whether the disease can or cannot invade the heterogeneous population with distributed susceptibility can be studied in the framework of the homogeneous model. The reason is that the considered population heterogeneity in susceptibility does not impact the basic reproductive number (28) (this holds, obviously, if we identify the mean value of β(ω) over the population of susceptibles at the initial time moment with the usual constant β in the homogeneous model). Here we note that this result is pertinent only to our particular model (1)–(3), since it is well known that in general population heterogeneity impacts R0 (e.g., [6, 18]).

From the other hand, the heterogeneity of the population has direct impact on the final size of the disease since equation (27) depends on the initial distribution in contrast to the homogeneous analogue z = exp{−R0(1−z)} (the last formula is valid under variety of different conditions [30]).

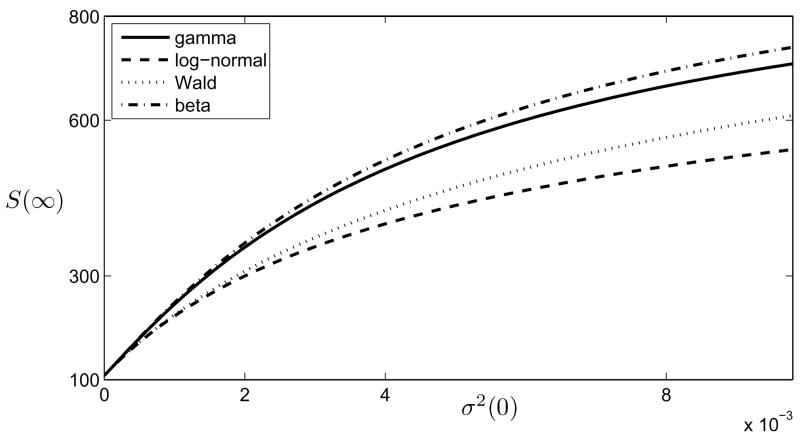

In Fig. 2 the final size of the susceptible population versus the initial variance of the parameter distribution is shown for four different initial distributions that have the same means at t = 0. From Fig. 2 it can be seen that the more heterogeneous the population of susceptibles, the less severe the disease not only in the short run (Proposition 3) but also globally (see [31] for the same result for frequency-dependent transmission). At the same time, it is worth emphasizing that the conditions β̄1(0) = β̄2(0), for two different initial distributions do not imply that z1 > z2, where zi are the solutions of (27). A counterexample can be easily found (e.g., taking the gamma-distribution with parameters k = 2, ν = 4 and the uniform distribution on the interval [0, 1], N/γ = 20, we find that z1 = 0.093 < z2 = 0.112 whereas σ1(0) = 1/8 > σ2(0) = 1/12).

Figure 2.

The size of the susceptible population that never gets infected, S(∞) versus the initial variance of the parameter distribution σ2(0) for four different initial distributions, β̄ (0) is the same in all cases. The parameters are S (0) = 999, I(0) = 1, γ = 20, β̄ (0) = 0.05

If we compare two distributions of the same family then sometimes it is possible to prove rigorously that, on the assumption of equal initial means and different second moments, more heterogeneous population (i.e., the one that has larger initial variance) experiences less severe disease. This is true, e.g., for two gamma-distributions:

Proposition 4

Assume that we have model (1)-(3) with two initial gamma-distributions with parameters k1, ν1 and k2,ν2 such that β̄1(0) = β̄2(0) and . Assume that R0 > 1. Then solutions of (27) that belong to (0, 1) are always satisfy z1 > z2.

Proof

We need to prove that

for any z ∈ (0, 1). This follows from the fact that f(r) = (k2 + r)k2/(k1 + r)k1 is monotonically increasing function for r > 0, i.e., f′ (r) > 0.

Remark

The last proposition can be extended to other initial distributions, e.g., it holds for the Wald distribution, for the uniform distribution and some others. However, for any distribution, for which more than two first moments are needed to specify all the parameters, an analogous proposition is no longer true.

6 Discussion and Conclusions

We have presented several results concerning the course of a disease in a closed heterogeneous population, where heterogeneity is mediated by invariable traits whose distributions are determined by population structure at every time moment. One of the purposes of the present text is to introduce in the area of epidemiological modeling the general techniques of the theory of heterogeneous populations [21, 23] which allow reduction of the initial infinite-dimensional dynamical system to an ODE system of a low dimension.

A usual strategy in the literature when analyzing systems similar to (1)–(3) is to consider an infinite-dimensional system of ODEs where the variables can be moments or cumulants of the corresponding distributions (e.g., [11, 33, 39]) and then analyze this system, or consider one of many possible moment-closure strategies to extract valuable information. Having the general theory outlined in Section 3 and the known results from the literature, we can critically discuss the latter and be prepared to possible pitfalls.

For example, in [11] the equation for the final epidemic size was obtained by using two different strategies: first, an initial gamma-distribution was assumed and analytical treatment was applied, and second, using the procedure suggested in [8], an approximation method was used in which the infinite-dimensional system of ODEs was replaced with two equations under the assumption that the coefficient of variation is constant. It is not surprising that Dwyer et al. obtained identical results because the gamma-distribution, according to the theory of heterogeneous populations, is the only continuous distribution which does not change its shape during the system evolution, and keeps the coefficient of variation constant (see Appendix). Therefore, the conclusion that “… the assumption of gamma-distributed susceptibility is not strictly necessary to derive equation [for the final epidemic size]” is not valid in many situations. Another initial distribution, how it is shown by (25), can yield another equation for the final epidemic size and, consequently, can produce significant discrepancy with the moment-closure approximation suggested by Dushoff [8].

The well known fact from the theory of heterogeneous populations that to model the system dynamics for a substantial time period we need to know the exact initial distribution implies that any results obtained for an epidemic in a heterogeneous population on the ground of knowledge of only several first moments of the initial distribution have to taken with extreme care. One, two, or more first moments of the initial distribution can be insufficient or even misleading. We also note that the short run behavior can be predicted when we have information only on several first moments (Section 5).

Another initial distribution which was used in the literature is the normal distribution [33] (see also Appendix, equation (34)). For the normal distribution we have that κi = 0, i ⩾ 3, where κi is the i-th cumulant. Combining the last property with the fact that the initial normal distribution remains normal within the framework of heterogeneous models we obtain that κi(t) = 0, i ⩾ 3, holds for any t (see Appendix). This was used in [33] to obtain an explicit solution to the equation

Here n(t, r) is the number of cells at time moment t, which are killed by antimicrobial agents with the kill rate r, and Kg is a constant (notations are changed from the original). First we note that, using Theorem 1, we obtain explicit solution of this equation for an arbitrary initial distribution of the kill rate:

where N(t) = ∫R n(t, r) dr. Second, the results from Sections 4 and 5 cannot be applied to the normal distribution because this distribution is defined from −∞ to ∞ and thus the corresponding mgf does not have a unique inverse. Which is more important, however, the total system dynamics can be influenced by these negative kill rates even if they occur with vanishingly small probability (we note that this issue is discussed in [33]). An example of such influence can be found in [24] where infinitely large growth rates occurring with small probabilities drive the population to explosion. Therefore any approximations based on an initial normal distribution in a situation where parameter can take only nonnegative values should be taken with care.

Summarizing the main results we can assert that the theory of heterogeneous populations can be successfully applied to many different mathematical models in epidemiology. Examples are given in Section 3. In many simple cases the original model can be reduced to a model described by ODEs, which simplifies the analysis. The law of mass action for a distributed susceptibility model implies a nonlinear incidence function in a homogeneous model. Moreover, one of the well known transmission functions, power relationship, follows in exact form from the initial gamma-distribution, at least in the case when exponents exceed one (Section 4). Therefore, a mechanistic derivation has been given to the transmission power function, which was shown previously to approximate real data with high accuracy. The short term behavior of the models considered can be approximately described knowing only two first moments of the initial distribution, whereas the long-term behavior depends on the exact initial distribution and can vary significantly (Section 5) even for the distributions whose several first moments are identical (Fig. 2).

It is a tempting challenge to include various demography processes to the analyzed models. The main obstacle is the need to specify the function φ(ω, ω′) similar to the one used in (5). The delta-function yields the models that can be analyzed using the general approach from Section 3 but it is usually difficult to interpret the underlying assumptions. These problems are the subject of ongoing research.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Dr. A. Bratus’ and Dr. G. Karev for insightful discussions and helpful suggestions. The constructive comments from the two anonymous reviewers are appreciated.

The author’s research is supported by the Department of Health and Human Services intramural program (NIH, National Library of Medicine).

A Appendix

In Appendix we collect the definitions of the distributions used throughout the main text. The definitions are taken from [19] and [20]. In addition to that we list some facts concerning evolution of these distributions if they are used as the initial distributions for the models studies in the text. Everywhere below it is assumed that β(ω) = ω. Inasmuch as we are interested in characteristics of distributions depending on time, the following formula is very useful (see [23]):

| (29) |

where q(t) in the solution of the corresponding auxiliary differential equation (see Theorem 1), M(t, λ) is the mgf of the parameter distribution at time t. Equation (29) shows that the mgf at any time instant can be expressed using the initial mgf.

Gamma-distribution

The pdf of gamma-distribution with parameters k and ν is given by

| (30) |

The mgf of gamma-distribution is M(0, λ) = (1 − λ/ν)−k.

It follows from (29) that for t > 0 the distribution does not change its form, i.e., it is gamma-distribution with parameters k and s − q(t). The mean and variance of the distribution are given by

Note that at any time moment the coefficient of variation is constant: . Actually, gamma-distribution is the only continuous distribution whose coefficient of variation remains constant with time within the outlined in Section 3 theory of heterogeneous models.

Wald distribution

The pdf of inverse gaussian (Wald) distribution with parameters μ and ν is

| (31) |

The mgf of Wald distribution is given by

Again the distribution remains the Wald distribution with parameters

and temporal characteristics of the distribution are

Beta-distribution

Sometimes it is useful to study evolution of distribution with compact support. A good candidate in this case is the family of beta-distributions with pdf

| (32) |

where B(r1, r2) is the beta-function.

The initial mean and variance are

Unfortunately in the case of beta-distribution it is impossible to write down the mgf, and, correspondingly, the temporal characteristics of the distribution. In a special case r1 = r2 = 1 we have a uniform distribution on [a, b]. Equation (29) shows that in this case for t > 0 the distribution is no longer uniform but turns into truncated exponential distribution.

In the text we used beta-distribution on [0, 1].

Log-normal distribution

The pdf of the log-normal distribution defined on the nonnegative half-axis ω ⩾ 0 with parameters μ and ν is

| (33) |

The initial characteristics are

As in the case of beta-distribution we cannot present explicit formulas for the mgf and other characteristics. We note that this distribution can be used only if q(t) < 0 for t > 0, otherwise the integral in the mgf diverges. This is the case, e.g., for the model (1)-(3), but not the case for (6)-(7), for which the log-normal distribution cannot be used (see also discussion in Section 3).

Normal distribution

The pdf is

| (34) |

The mgf is . The temporal characteristics are

We present here the normal distribution because it was used in a number of papers. Using the normal distribution for the considered models is not always appropriate because the parameter takes the values from −∞ to ∞ whereas usually all the parameters have definite signs. To overcome this difficulty a truncated normal distribution can be used, albeit without simple analytical expressions.

Poisson distribution

In the same spirit discrete distributions can be managed. Consider, e.g., the Poisson distribution with parameter θ, i.e,

| (35) |

then M(0, λ) = exp {θ (eλ − 1)}, and

Other possible initial distribution can be considered in a similar vein.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ackleh AS. Estimation of rate distributions in generalized Kolmogorov community models. Nonlinear Analysis. 1998;33(7):729–745. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ackleh AS, Marshall DF, Heatherly HE. Extinction in a generalized Lotka – Volterra predator–prey model. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Stochastic Analysis. 2000;13(3):287–297. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ackleh AS, Marshall DF, Heatherly HE, Fitzpatrick BG. Survival of the fittest in a generalized logistic model. Mathematical Models and Methods in Applied Sciences. 1999;9(9):1379–1391. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson RM, May RMC. Infectious Diseases of Humans: Dynamics and Control. Oxford University Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diekmann O, Heesterbeek JAP. Analysis and Interpretation. John Wiley; 2000. Mathematical Epidemiology of Infectious Diseases: Model Building. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diekmann O, Heesterbeek JAP, Metz JAJ. On the definition and the computation of the basic reproduction ratio R0 in models for infectious diseases in heterogeneous populations. Journal of Mathematical Biology. 1990;28(4):365–382. doi: 10.1007/BF00178324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diekmann O, Heesterbeek JAP, Metz JAJ. The legacy of Kermack and McKendrick. In: Mollison D, editor. Epidemic Models: Their Structure and Relation to Data. Cambridge University Press; 1993. pp. 95–115. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dushoff J. Host Heterogeneity and Disease Endemicity: A Moment-Based Approach. Theoretical Population Biology. 1999;56(3):325–335. doi: 10.1006/tpbi.1999.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dushoff J, Levin S. The effects of population heterogeneity on disease invasion. Mathematical Biosciences. 1995;128(1–2):25–40. doi: 10.1016/0025-5564(94)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dwyer G, Dushoff J, Elkinton JS, Burand JP, Levin SA. Host heterogeneity in susceptibility: Lessons from an insect virus. In: Diekmann U, Metz JAJ, Sabelis M, Sigmund K, editors. Adaptive Dynamics of Infectious Diseases: In Pursuit of Virulence Management. Cambridge Univercity Press; 2002. pp. 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dwyer G, Dushoff J, Elkinton JS, Levin SA. Pathogen-Driven Outbreaks in Forest Defoliators Revisited: Building Models from Experimental Data. The American Naturalist. 2000;156(2):105–120. doi: 10.1086/303379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dwyer G, Elkinton JS, Buonaccorsi JP. Host Heterogeneity in Susceptibility and Disease Dynamics: Tests of a Mathematical Model. The American Naturalist. 1997;150(6):685–707. doi: 10.1086/286089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haas VJ, Caliri A, da Silva MAA. Temporal Duration and Event Size Distribution at the Epidemic Threshold. Journal of Biological Physics. 1999;25(4):309–324. doi: 10.1023/A:1005115117228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heesterbeek JAP. The law of mass-action in epidemiology: a historical perspective. In: Beisner BE, editor. Ecological Paradigms Lost: Routes of Theory Change. Academic Press; 2005. pp. 81–104. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hochberg ME. Non-linear transmission rates and the dynamics of infectious disease. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1991 Dec;153(3):301–321. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(05)80572-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu Schmitz S. Effects of genetic heterogeneity on HIV transmission in homosexual populations. In: Castillo-Chavez C, editor. Mathematical approaches for emerging and reemerging infectious diseases: Models, methods, and theory. Vol. 126. IMA; 2002. pp. 245–260. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyman JM, Li J. Differential susceptibility epidemic models. Journal of Mathematical Biology. 2005;50(6):626–644. doi: 10.1007/s00285-004-0301-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacquez JA, Simon CP, Koopman J. Core groups and the R0s for subgroups in heterogeneous SIS and SI models. In: Mollison D, editor. Epidemic Models: Their Structure and Relation to Data. Cambrige University Press; 1995. pp. 279–301. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson NL, Kotz S, Balakrishnan N. Continuous Univariate Distributions. Vol. 1. John Wiley; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson NL, Kotz S, Balakrishnan N. Continuous Univariate Distributions. Vol. 2. John Wiley; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karev GP. Heterogeneity effects in population dynamics. Doklady Mathematics. 2000;62(1):141–144. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karev GP. Inhomogeneous models of tree stand self-thinning. Ecological Modelling. 2003;160(1–2):23–37. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karev GP. Dynamics of Heterogeneous Populations and Communities and Evolution of Distributions. Discrete and Continuous Dynamical Systems. 2005;(Suppl):487–496. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karev GP. Dynamics of inhomogeneous populations and global demography models. Journal of Biological Systems. 2005;13(1):83–104. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karev GP, Novozhilov AS, Koonin EV. Mathematical modeling of tumor therapy with oncolytic viruses: Effects of parametric heterogeneity on cell dynamics. Biology Direct. 2006;1(30):19. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-1-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kermack WO, McKendrick AG. A Contribution to the Mathematical Theory of Epidemics. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series A. 1927;115(772):700–721. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knell RJ, Begon M, Thompson DJ. Transmission dynamics of Bacillus thuringiensis infecting Plodia interpunctella: a test of the mass action assumption with an insect pathogen. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B: Biological Sciences. 1996 Jan;263(1366):75–81. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1996.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu WM, Hethcote HW, Levin SA. Dynamical behavior of epidemiological models with nonlinear incidence rates. Journal of Mathematical Biology. 1987;25(4):359–380. doi: 10.1007/BF00277162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu WM, Levin SA, Iwasa Y. Influence of nonlinear incidence rates upon the behavior of SIRS epidemiological models. Journal of Mathematical Biology. 1986;23(2):187–204. doi: 10.1007/BF00276956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma J, Earn DJD. Generality of the Final Size Formula for an Epidemic of a Newly Invading Infectious Disease. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology. 2006;68(3):679–702. doi: 10.1007/s11538-005-9047-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.May RM, Anderson RM. The transmission dynamics of human immunodeficiency virus. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B: Biological Sciences. 1988;321(1207):565–607. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1988.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCallum H, Barlow N, Hone J. How should pathogen transmission be modelled? Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2001;16(6):295–300. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(01)02144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nikolaou M, Tam VH. A New Modeling Approach to the Effect of Antimicrobial Agents on Heterogeneous Microbial Populations. Journal of Mathematical Biology. 2006;52(2):154–182. doi: 10.1007/s00285-005-0350-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Novozhilov AS. Analysis of a generalized population predator–prey model with a parameter distributed normally over the individuals in the predator population. Journal of Computer and System Sciences International. 2004;43(3):378–382. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ross R. The Prevention of Malaria. J. Murray; London: 1910. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roy M, Pascual M. On representing network heterogeneities in the incidence rate of simple epidemic models. Ecological Complexity. 2006;3(1):80–90. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Severo NC. Generalizations of Some Stochastic Epidemic Models. Mathematical Biosciences. 1969;4:395–402. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stroud PD, Sydoriak SJ, Riese JM, Smith JP, Mniszewski SM, Romero PR. Semi-empirical power-law scaling of new infection rate to model epidemic dynamics with inhomogeneous mixing. Mathematical Biosciences. 2006 Oct;203(2):301–318. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Veliov VM. On the effect of population heterogeneity on dynamics of epidemic diseases. Journal of Mathematical Biology. 2005;51(2):123–143. doi: 10.1007/s00285-004-0288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]